German-language press in the Netherlands

A German-language press in the Netherlands in the form of a daily or weekly press developed later than other structures outside of today's border area, and for a long time a number of obstacles stood in the way of its creation. The National Socialist takeover of power in 1933 led to the establishment of exile papers in the Netherlands. After the occupation of the country in 1940, these had to be given up, and now both an occupation newspaper and a resistance press followed. Since the end of the Second World War, there has been no German-speaking press landscape in the Netherlands, and new and re-establishments were mostly short-lived. Characteristics of the German-language media in the Netherlands were, depending on the title, short-lived, low distribution, dependence on subsidies or forced discontinuation due to external adversity, the permanent establishment of a significant representative did not succeed.

Obstacles to the establishment of a German-language press and the special case of the Duchy / Province of Limburg

Within the German congregation in the Netherlands , a German-language press emerged later than other institutions, so the oldest German-speaking congregation was founded as part of the Dutch Reformed Church as early as 1620 , and German schools had existed since the middle of the 19th century, but the Randstad with its great economic importance initially remained without a German-language newspaper. An exception was the Holländische Zeitung , published during the revolt against the Orange from 1785 to 1787 , which, according to the will of its Dutch founder, was supposed to oppose “wrong ideas of the Germans” towards the Netherlands (accordingly the subtitle Truth and Virtue as the goal ). It appeared twice a week with the assistance of a German pastor from Amsterdam , who translated the texts.

The Duchy of Limburg occupies a special position, which was part of the German Confederation until 1866 , but was primarily a Dutch province . From 1847, the Limburger Courier appeared in Heerlen as the successor to a less successful Dutch- language weekly newspaper , which in October 1868 returned to the language of its predecessor, possibly in order to reach all of South Limburg. In order to accommodate the German-speaking readership, the newspaper received a corresponding supplement from September 1869. The Kirchrather Volkszeitung was later published weekly in Kerkrade from 1907 to 1911 . The short-lived Dutch-language successor Nieuwe Kerkraadsche Courant continued to contain German advertisements, letters to the editor and feature sections for a long time. The Limburger Tageblatt , which appeared for a few years after the First World War , hardly dealt with Limburg and was otherwise identical in content to the Aachen Echo of the present , probably aimed at the German miners living in the province. In Vaals there was the Limburger Volksfreund printed in German Fraktur script from 1902 . The bilingual Vaalser Anzeiger appeared until the 1930s , possibly a successor to the Limburger Volksfreund and contained a German-language church gazette.

There were several reasons for the long lack of a German-language press in the rest of the country: Until 1869 there was the Dagbladzegel ( newspaper stamp ), which stood for the high taxation of newspapers in the Netherlands. This alone made it difficult to found and establish a German-language newspaper. For example, it was also not possible to win a Catholic and a Protestant readership at the same time (see also the particularism in the form of pillaring that was developing in the Netherlands at that time ). In principle, newspapers like the Kölnische Zeitung could be bought in the Netherlands, but these were very expensive due to the tax. Foreign newspapers could, however, be read in social associations and coffee houses , as well as in reading societies which were very popular in the Netherlands during the 19th century.

Abolition of the newspaper stamp and press until the seizure of power in Germany in 1933

The abolition of the Dagbladzegel ensured that newspapers became considerably cheaper. However, the German-language press of the second half of the 19th century was initially almost entirely related to the Netherlands as a trading center, so there was the weekly market report as well as the Handels- und Schiffahrts-Zeitung , Allgemeine Kaffeezeitung , Dutch news newspaper for trade, industry, art and science and Dutch Trade and Shipping Newspaper.

The German weekly newspaper in the Netherlands (from 1906 German weekly newspaper for the Netherlands and Belgium ) was published in Haarlem from 1893 and later in Amsterdam , founded by August Prell , who was born in Bavaria and worked for a time in the colonial army in the Dutch East Indies . However, this found it difficult to keep afloat and was subsidized by the German side during the First World War, as it was not advisable to stop the newspaper at that time. It was sometimes "good" for one or the other conflict, from a process that Prell led in 1900 against a former employee who had published a German anti-cheating newspaper in the Netherlands , to a complaint by Walther Rathenau , who was very upset about the way he was portrayed. In spite of its relatively long existence, the effect of the newspaper outside of the German readership is likely to have been small; it is sometimes not even mentioned in Dutch historical press literature.

In 1911 another weekly newspaper, the Deutsche Zeitung in Amsterdam , was added, which was also distributed outside the Netherlands. The editor-in-chief was the German-Austrian Heinrich Poeschl, who had left Vienna because of a prison sentence. The paper was noticeable for its anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic tirades. Poeschl also attacked his competitor Prell for alleged behavior that was damaging to business. Consul General Rienacker, according to Prell, with whom he did not have a good relationship, invested out of his own pocket in the newspaper, but this did not prevent it from ending after a year.

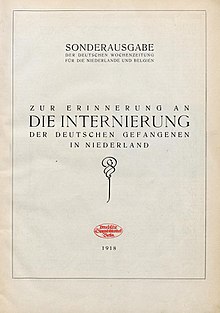

During the final months of the First World War, Germans interned in the Netherlands published a newspaper for prisoners . The Deutsche Zeitung appeared in The Hague in a partly bi-monthly, partly monthly publication frequency. After the war, the German weekly newspaper for the Netherlands and Belgium shortened its name to German weekly newspaper for the Netherlands , so far there is no information on the question of the reason, for example whether it could no longer appear because of the war.

In 1931 there was another short-lived start-up, the Rotterdam Dutch newsreel. German newspaper for Rotterdam, The Hague and Dordrecht. The Amsterdam German-Dutch Rundschau also only stayed on the market for a short time two years later.

German exile papers since 1933 and press during the German occupation in World War II

After the seizure of power in Germany, the Netherlands became the place of appearance of some organs in exile; The social democratic exile newspaper Freie Presse , the literary magazine Die Sammlung , published by Klaus Mann , and the weekly Der Deutsche Weg founded by the Jesuit Friedrich Muckermann and Josef Steinhage have become particularly well known . Wolfgang Cordan gave together with the Dutch authors Gerard den Brabander and Jac. van Hattum with participation u. a. by Yvan Goll and Odd Eidem 1939 multilingual Centaur out, but from him before the war, only two issues appeared.

The free press emerged as an idea within the social democratic party SDAP . Started in July 1933 as a weekly newspaper with great ambitions and a German editorial team, whose management was in the hands of Helmut Kern and Emil Groß , the main aim was to reach the border area. The Prague leadership in exile of the SPD Sopade did not provide any financial support; the newspaper was initially financed by the NPV union , the SDAP and the De Arbeiderspers publishing house . The newspaper ran worse than expected, the NVV and SDAP bailed out again. Difficult working conditions - political activity by Germans was officially banned in the Netherlands, which is why the editorial team acted anonymously - did the rest. The newspaper was discontinued in January 1934.

Klaus Mann was able to win numerous prominent authors, including his father Thomas Mann , for his literary magazine Die Sammlung , published by the Amsterdam Querido Verlag under the patronage of André Gides , Aldous Huxley and his uncle Heinrich Mann . In the first issue, Klaus Mann surprisingly announced that he was also pursuing political ambitions with the magazine. This led to the intervention of German publishers against employees of the magazine, since a commitment to collection could lead to a publication ban in Germany. This led to the distancing of Thomas Mann and Alfred Döblins , René Schickeles and Stefan Zweig . The magazine was still continued, but could not sell enough copies and was discontinued in August 1935.

Friedrich Muckermann and Josef Steinhage founded Deutsche Weg , which appeared in August 1934, as the successor to Muckermann's Katholische Nachrichten and Steinhage's small Catholic German Post for Holland . In the end it was practically bankrupt, although the Dutch section of the International Community for the Protection of Young Women recommended it to all German associations (the association had the numerous (Catholic) German maids in the country in mind). The newspaper was supposed to show the incompatibility of National Socialism and Christianity . Exposed to great German pressure, financial problems, informers and other difficulties, on the other hand receiving all sorts of help, it was only the German campaign in the west that forced the discontinuation of the German Way , even after Muckermann had to work from Rome for a time and a Dutchman had to be appointed as the official editor-in-chief. However, the newspaper could not achieve a greater impact.

National Socialist Germany did not simply leave the field to the exiles and, from March 4, 1939 , published the Reichsdeutsche Nachrichten in the Netherlands via the Dutch part of the NSDAP (AO) , the Reichsdeutsche Gemeinschaft, which , however, were of insignificant importance. The German weekly newspaper had placed itself under the new order after 1933.

The situation changed suddenly with the occupation of the Netherlands in 1940. Just three weeks after the country's surrender, the German newspaper in the Netherlands appeared in Amsterdam every weekday as a replacement for the Reichsdeutsche Nachrichten , which included residents, soldiers and occupation personnel as well as Dutch people tried to achieve and influence in the interests of the Nazi regime; However, their attempts to bring National Socialism closer to the Dutch were unsuccessful. In addition, the soldiers 'newspapers Marine in Holland and Zeelander Wachtposten were published , the latter having the same content as a number of soldiers' newspapers intended for the Atlantic coast. The new situation meant the end of the German weekly newspaper , which was discontinued in spring 1942. August Prells son Hans Prell, who took over the newspaper, shifted its activities to the since 1941 German Dutch by the cultural community issued monthly magazine of the Dutch-German Cultural Community (Dutch title Maandblad the Nederlandsch-Duitsche Kultuurgemeenschap. Until 1942 with the suffix "monthly magazine “), Which existed until 1944.

In addition to the occupation press, there was also a German-language underground press such as the eponymous organ of the Holland Group Free Germany and the bulletin of the Antifascist German Interest Group ; In the last days of the occupation, there were also a number of attempts to use leaflets to persuade the German soldiers to give up, examples of which are the Free Press - German edition for the Wehrmacht , news for the troops and the German soldier newspaper for the Netherlands . The Free Word is a special case . This newspaper was the idea of the hiding soldier (actually a journalist) Karl Ernst Eikens, which he printed together with a Dutch resister and wanted to distribute especially in Germany. However, Eikens was arrested and shot after crossing the border. At the latest with the German surrender in 1945, all of the aforementioned publications came to an end.

Short-lived start-ups and re-foundations after the Second World War, remaining publications

Centaur experienced a brief rebirth after the Second World War with a partially different editorial team, but still with Cordan's participation. Otherwise, attempts have been made to establish a new medium every now and then, but this has not been successful. This applied to the German-Dutch joint newspaper Quod , which was delivered to schools free of charge in 1962, as well as to the magazines Aha - The Current Holland Experience (1994) and Holland-Magazin (2009), which were conceived as a lifestyle magazine by Dutch publishers published and expelled on both sides of the border, could not establish themselves either.

From 1950 to 2007 the magazine Castrum Peregrini appeared with five issues a year , which has been supported by the foundation of the same name since 1962 and dealt with literature, art and intellectual history; as it was provided with a cardboard cover, it is a bit out of the ordinary here.

There are still some publications aimed at a special audience, such as the Amsterdam contributions to older German studies or more recent German studies, as well as community letters from German-speaking parishes , with what was said about Castrum Peregrini applies to the former . Apart from the exceptions mentioned, however, the era of a German-language press in the Netherlands can be regarded as extinct for the time being since World War II.

Web links

The Royal Library of the Netherlands makes some German-language newspapers published in the Netherlands available for viewing in digitized form, and the website is in Dutch.

- German newspaper in the Netherlands

- During the German occupation, the resistance leaflets / pamphlets distributed: German soldier newspaper for the Netherlands , Free Press - German edition for the Wehrmacht , The Free Word , Holland Group Free Germany , Bulletin of the Interest Group Anti-Fascist German , News for the Troops

Further digital archive:

Individual evidence

- ↑ Germans in the Netherlands 1918 to 1945 , NiederlandeNet of the Westphalian Wilhelms University , by Katja Happe.

- ↑ Jan Izaak van Doorninck: Vermomde en naamlooze schrijvers opgespoord op het gebied der Nederlandsche en Vlaamsche letteren. BM Israël, Amsterdam 1970 (reprint of the 1885 edition), Volume 2 “Naamlooze geschriften”, p. 674. Online edition , alternative PDF edition.

- ↑ Predecessor of the Limburger Courier after Ann Mary Genealogie: Limburgers become Nederlanders? In: Taal & Tongval. Topic number 17: Taalvariatie en groepsidentiteit. Amsterdam University Press , Amsterdam 2004, p. 78 (with German summary, online ( PDF )), remainder after Wolfgang Cortjaens, Jan de Maeyer, Tom Verschaffel: Historism and Cultural Identity in the Rhine-Meuse Region / Historicism and cultural identity in space Rhine-Meuse . Leuven University Press, Leuven 2008, ISBN 978-90-5867-666-5 , pp. 118-120.

- ↑ Marlou Schrover: Een van colony Duitsers. Groepsvorming onder Duitse immigranten in Utrecht in de negentiende eeuw . Aksant, Amsterdam 2002, ISBN 90-5260-066-X , pp. 174-175 ( online as PDF ) and " Het dagbladzegel ( Memento of the original from September 29, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. “, Politiekcompendium.nl .

- ↑ Marlou Schrover: Een van colony Duitsers. Groepsvorming onder Duitse immigranten in Utrecht in de negentiende eeuw . Aksant, Amsterdam 2002, ISBN 90-5260-066-X , p. 175 ( online as PDF ).

- ↑ German weekly newspaper in the Netherlands , German weekly newspaper for the Netherlands and Belgium in the catalog of the German National Library a. Genootschap Amstelodamum (Ed.): Jaarboek Amstelodamum 1928 . Genootschap Amstelodamum, Amsterdam 1928, pp. 219-220 (contained on Genootschap Amstelodamum 1900-2000. Alle Jaarboeken & Maandbladen . Stichting Historic Future, Amsterdam 2000, ISBN 90-76650-11-X ).

- ↑ On the German Anti-Prellerei-Zeitung in the Netherlands cf. “Rechtzaaken: Beleeding.”, Algemeen Handelsblad , November 5, 1900, p. 2, “Volledig eerherstel.”, Het nieuws van den dag , November 7, 1901, p. 11 u. Entry of the newspaper in the catalog of the International Institute for Social History . Anger Walther Rathenau after Nicole Eversdijk: Culture as a political advertising medium . Waxmann Verlag, Münster 2010, ISBN 978-3-8309-2308-4 , pp. 216-218. Revised and abridged dissertation, Münster 2007.

- ↑ In Jan van de Plasse's Kroniek van de Nederlandse dagblad- en opiniepers , for example, it is missing (Jan van de Plasse: Kroniek van de Nederlandse dagblad- en opiniepers / samengesteld door Jan van de Plasse. Red. Wim Verbei. Otto Cramwinckel Uitgever, Amsterdam 2005 , ISBN 90-75727-77-1 ).

- ↑ Distribution area according to Nicole Eversdijk: Culture as a political advertising medium . Waxmann Verlag, Münster 2010, ISBN 978-3-8309-2308-4 , p. 215. Revised and abridged dissertation, Münster 2007. Origin Poeschl after André Beening: Onder de vleugels van de adelaar. De Duitse buitenlandse politiek ten anzien van Nederland in the period 1890–1914 . Dissertation, Amsterdam 1994, p. 111. Punishment after Mededeelingen van den Nederlandsche Journalistenkring. Number 149, October 1912, p. 123.

- ↑ André Beening: Onder de vleugels van de adelaar. De Duitse buitenlandse politiek ten anzien van Nederland in the period 1890–1914 . Dissertation, Amsterdam 1994, pp. 111-112 u. Nicole Eversdijk: Culture as a political advertising medium . Waxmann Verlag, Münster 2010, ISBN 978-3-8309-2308-4 , pp. 215-216. Revised and abridged dissertation, Münster 2007.

- ^ German newspaper in the catalog of the German National Library.

- ^ German weekly newspaper for the Netherlands in the catalog of the German National Library.

- ^ Entry of the newspaper in the catalog of the International Institute for Social History .

- ^ Entry of the newspaper in the catalog of the International Institute for Social History .

- ^ Friedrich Johannes Muckermann in the Lexicon of Westphalian Authors

- ↑ Gruber, Hubert, "Muckermann, Friedrich" in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 18 (1997), pp. 258–260 (online version) and " The German Way, anti-Nazi weekblad van voor de oorlog, en het vervolg ", Transisalania - Overijssels allerlei , October 16, 2010.

- ^ Cor de Back: The magazine "Het Fundament" and the German exile literature. In: Amsterdam contributions to recent German studies. Rodopi, Amsterdam 1977, ISSN 0304-6257 , Volume 6, p. 188, as well as “ De Amsterdamsche School wordt Amsterdamer Schule. Maar waarom? “, Menno ter Braak , Het Vaderland , August 8, 1939 a. Tijdschrift voor tijdschriftstudies , edition 3/1998, Centaur, 1945–1948: een koers tussen herstel en vernieuwing. P. 6 ( content as PDF ).

- ↑ Free press: geschiedenis u. Free press: digital versie , Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis .

- ↑ Historical Commission of the German Publishers and Booksellers Association (Hrsg.): Archive for the history of the book industry . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2000 (volume 53) / 2001 (volume 54), ISSN 0066-6327 , pp. 28-31 (volume 53) and pp. 10-11 (volume 54).

- ^ Hanno Hardt, Elke Hilscher, Winfried B. Lerg (eds.): Press in Exile . Saur, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-598-02530-0 , p. 205 and “RK Meisjesbescherming”, De Tijd , May 26, 1933, p. 10.

- ^ Hanno Hardt, Elke Hilscher, Winfried B. Lerg (eds.): Press in Exile . Saur, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-598-02530-0 , pp. 205-212.

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 63 and Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: Organization and control of journalism. Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 80.

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 63.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism. Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , pp. 78, 81-83 and. 91.

- ^ Entries in the catalog of the German National Library for the Navy in Holland and Zeeland Wachtposten as well as Heinz-Werner Eckhardt: Die Frontzeitungen des Deutschen Heeres 1939-1945 . Wilhelm Braumüller University Publishing House, Vienna / Stuttgart 1975, p. 91.

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 468.

-

^ Entry of the monthly in the catalog of the International Institute for Social History .

Archive of the cultural community at the Dutch Institute for War Documentation .

Archive piece 56 in the archive of the cultural community at the Dutch Institute for War Documentation .

Christoph König (Ed.), With the collaboration of Birgit Wägenbaur u. a .: Internationales Germanistenlexikon 1800–1950 . Volume 1: A-G. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-015485-4 , p. 57. - ↑ On the here listed and other German-language resistance publications cf. Lydia E. Winkel: De Ondergrondse Pers 1940–1945 . Rijksinstituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie , Amsterdam 1989, ISBN 90-218-3746-3 (originally published by Veen, The Hague 1954). Online edition ( PDF ) under CC-BY-SA 3.0 license . Since the titles are distributed throughout the book within an alphabetically sorted list, no page numbers are given here. Full name from Eikens to Louis de Jong : Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog . 14 parts, 1969-1991, SDU, The Hague. Here part 7, second half, p. 1051, footnote 1.

- ↑ Tijdschrift voor tijdschriftstudies , edition 3/1998, Centaur, 1945–1948: een koers tussen herstel en vernieuwing. P. 4–7 ( content as PDF ), Index op Centaur, 1945–1948. P. 8–20 ( content as PDF ).

- ^ Entry of the newspaper in the catalog of the International Institute for Social History . A negative review of the first edition appeared in the communist Waarheid (“Wat is Quod?”, November 10, 1962, p. 3).

- ↑ On Aha - The current Holland experience cf. Horizont from May 20, 1994, p. 33 ( online ), on Holland-Magazin cf. Entry in the catalog of the German National Library, kress.de , March 13, 2009 a. “ Anything but a cheese sheet ”, Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung of July 21, 2009.

- ^ History of the Castrum Peregrini Foundation a . " There will be no such journal again ", Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of April 17, 2008. Information in the catalog of the German National Library.

- ↑ Amsterdam contributions to older German studies ( Memento of the original from April 29, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. u. Amsterdam contributions to more recent German studies in Brill , last accessed on June 20, 2015. For the community letters cf. List of parishes abroad of the Evangelical Church in Germany (parish letters in the corresponding entries in the list) and Der Rafaelsbote , German-speaking Catholic community in the Netherlands, last accessed on June 20, 2015.