German newspaper in the Netherlands

The German newspaper in the Netherlands ( DZN ) was a supraregional German-language daily newspaper with an editorial office in Amsterdam , which was published almost continuously in the German- occupied Netherlands during the Second World War from June 5, 1940 to May 5, 1945, the day of the German surrender in the " Fortress Holland " appeared. It was part of a network of German occupation newspapers that was systematically built up during the German conquest campaigns and gradually disintegrated as a result of the Allied reconquests.

Like its sister newspapers, the DZN served as a mouthpiece for the occupying power and was aimed at a German, but in their case also a Dutch audience; however, it did not succeed there in attracting a significant readership outside certain circles, although conceptual concessions had been made to the Dutch market. Despite the high demands it placed on itself, the newspaper could not deny its origins; the tone of Nazi propaganda was widespread in it. In the end, the manufacturing conditions were so precarious that it looked more like a leaflet than a newspaper, but its publication was maintained until the end.

Foundation phase

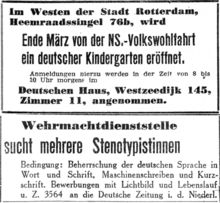

The DZN replaced the Reichsdeutsche Nachrichten in the Netherlands , which had been published weekly since March 4, 1939 by the Reichsdeutsche Gemeinschaft, the Dutch part of the NSDAP (AO) . With the German weekly newspaper for the Netherlands , another German-language newspaper appeared in 1893, which was discontinued in spring 1942. Rotterdam, with its German colony, which was particularly influential in business circles , was initially the ideal location , as the Reichsdeutsche Nachrichten was located there not far from the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant , but it had already reached full capacity thanks to other external contracts. The now contacted Algemeen Handelsblad from Amsterdam rejected the request and received instructions from Wehrmacht Commander Christiansen to cooperate, but was able to convincingly demonstrate that only capacities were available for the sentence . Finally, the Telegraaf published by the Holdert group was found for printing ; Whether a good offer, coercion or caution - after an originally pro-German attitude at the beginning of the First World War , the Telegraaf had made a complete U-turn - the decisive factor is not known. Due to these difficulties, the DZN could not inherit its predecessor immediately on June 1st as planned.

The publisher of the DZN, as well as all other occupation newspapers with the exception of the military newspapers published by the Wehrmacht , was Europa-Verlag, a subsidiary of Franz-Eher-Verlag under Max Amann and managed by Rolf Rienhardt . Georg Biedermann was appointed as the publishing director, who was also head of the special department for publishing in the general commissioner for special use under Fritz Schmidt . In contrast to its predecessor, which was of marginal importance, the DZN was to compete with the Dutch press from the start. The recently founded German newspaper in Norway served as a direct model. As early as July 1940, a stock corporation was founded in order to publish the newspaper as well as books, illustrations, magazines and other printed matter from then on. However, only a small number of publications can be proven, so in the same year a book was published with articles on German-Dutch economic relations that had previously appeared, and various maps of theaters of war were later offered for sale in the DZN , but apart from that, it is only known that the publisher probably printed soldiers' newspapers for the armed forces.

The aim of the newspaper was to influence the formation of public opinion in the Netherlands, especially the Germans there (residents, occupation personnel, soldiers) in the interests of the Nazi regime . At the time of the German attack in the Netherlands 52,000 lived Reich German (excluding refugees), the majority of whom had no connection to a Nazi organization. The Dutch, who were elevated to a “Germanic brother people” by the racial ideology , should also be addressed, which was obvious because of their widespread knowledge of German, but so far only a modest number of them had shown greater sympathy for National Socialism . Accordingly, the objectives that the DZN incorporated into its conception were varied in order to address them equally to potential reader groups from their point of view, so that, unlike most of the other newspapers of Europa-Verlag, it was not a provincial or home newspaper.

Similar to its sister newspapers, the DZN brought German editors from the Cologne West German Observer (WB) and other Nazi newspapers into the editorial office, which employed ten people in early 1942 and remained relatively constant until the end of the war; the newspaper also had branches in Berlin , The Hague and Rotterdam. The Berlin editors forwarded the instructions of the Propaganda Ministry and other German government agencies, while the branch in The Hague kept in touch with the occupation administration and received the press instructions . The first editor-in-chief was Emil Frotscher , who was one of the founders of the NS flagship newspaper Das Reich , initiated by Rienhardt . He left the newspaper in December 1940 to take up the post of deputy editor-in-chief at the Pariser Zeitung , a new sister of the DZN. Frotscher's successor, Hermann Ginzel, who came from the WB and continued to work for it, only stayed a few months and then returned to his master sheet.

The first few months were difficult, so the editors first had to familiarize themselves with the conditions in the country and learn the Dutch language . Editor-in-chief Frotscher reported communication problems with the technical staff, who came from local printing companies. In the first few weeks there wasn't even a telephone or teletype , only a radio and postal courier were available.

The publishing house, editorial office and technology were initially housed in separate buildings on Voorburgwal , known for decades as Amsterdam's Fleet Street . In the autumn of 1942, the editorial team moved into the Telegraaf building , where the publishing house was already located. The sentence was then moved there, which ultimately brought all areas of the DZN together under one roof. In the spring of that year there had also been talks about buying the Telegraaf , but this did not materialize because of the high price. The printing of the DZN by the Holdert group was one of the reasons for banning the Telegraaf and its header De Courant / Het Nieuws van den Dag as collaboration newspapers from 1945 to 1949.

Frequency of publication, scope and structure

The DZN was published every weekday, initially Monday to Saturday afternoon with eight pages and Sunday mornings with 12 to 14 pages. In 1941, when the lack of resources had not yet materialized, an anniversary series and special editions for trade fairs ( Leipziger Messe , Jaarbeurs Utrecht ) could be printed with a significantly higher number of pages than usual. War-related restrictions drastically reduced the size of the Dutch newspapers, but this applied to a lesser extent to the DZN, as it was given preferential treatment within the fixed paper quotas - it received around 7.5% of the share granted to daily newspapers since September 1941, and later even more . In addition, the subscription price was cheaper than that of most of the country's top national newspapers. The Dutch newspapers had already been forbidden in September 1940 to make price changes due to the reduced number of pages.

As a newspaper with a serious self-image, the DZN wanted to meet high standards and took the appearance and the diversity of the German newspapers Das Reich and Frankfurter Zeitung as a model. The rubrics corresponded to the usual division into politics, economy, culture, sport and advertisements, according to Frotscher, however, when designing the newspaper, although a deliberate adaptation to the Dutch press was not intended, its special position had to be taken into account and a “clear Clarity of the pages, tight structure, good mix of opinion and news section [and] strongest illustration ”, furthermore the“ Dutch method of illustrating news from the archive material ”has been adopted, which has“ extensive use of map sketches ” completes the illustration. As with all other printed matter intended for foreign countries, Antiqua was used as the font instead of Fraktur , which was preceded by a corresponding arrangement.

Content and positioning

Rubrics and Authors

The content of the DZN consisted mainly of news and reports, while with the exception of general announcements by the Reichskommissariat, the conditions and situation in the Netherlands were rarely discussed. The news and political section included editorials and comments, as well as correspondent and PK reports , written by well-known representatives of the Nazi regime and the military . In addition to high-ranking National Socialists such as the Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels , Reich Press Chief Otto Dietrich and Reich Commissioner Seyß-Inquart , names such as Hans Friedrich Blunck , Walter Groß , Karl Haushofer , Erich Hilgenfeldt , Fritz Hippler , Curt Hotzel , Otto Marrenbach were found in the editorials and Giselher Wirsing .

The newspaper saw the “page of the day” as its showpiece, which came up with a particularly large number of images and relied on series of articles and reports. True to its concept of adapting to the strong images of the Dutch press, the DZN also received a special photo page with “Pictures of the Day”. The local section mostly served as a kind of “travel guide in continuations” (Gabriele Hoffmann), in which Dutch sights were reported. In addition, there were serial novels, short stories, reviews and cultural discussions, articles were taken from other newspapers, and translations were also included. A frequently recurring theme in the serial novels was seafaring, the great importance of which for the Netherlands aroused great interest among Germans. Otherwise, the obligatory speeches by Hitler and Goebbels, appeals from Göring or an interview with Reichskommissar Seyß-Inquart could not be missing.

The intended bridging function should also be seen from the outset in the business and sports section, for example through a request to expand business relations or a report on national training competitions for Dutch athletes. The same function was also attempted through contributions and quotes from Dutch authors and artists such as Max Blokzijl (pro-German propaganda spokesman ), Ben van Eysselsteijn and Jonny Heykens . This courting of “Germanic” authors stood in contrast to the occupation newspapers published in the Reichskommissariat Ostland , which Alfred Rosenberg had forbidden to involve local authors. Blokzijl and van Eysselsteijn were also well known in Germany; for the latter, the DZN relied on the foreign rights of its novel "Vom Südkreuz zum Polarstern", which had already been sold before the war. Van Eysselsteijn later complained about his powerlessness and that he had protested the publication of two texts - according to him, pre-war articles that were republished without his consent. In a letter at the time, however, he expressed his delight in having his novel published.

The newspaper also tried to send a message in the opposite direction; The German writer Ludwig Bäte , author of the volume of short novels “Herz in Holland” published in 1936 and a close friend of van Eysselsteijn's after the war, published in the DZN. In addition, the DZN did not fail to settle accounts thoroughly with the exile literature , especially with the Querido Verlag , at an early stage .

Propaganda and surveillance

Amann later claimed after his arrest that there should have been more than just Nazi propaganda in his occupation newspapers, since they were intended for foreign countries and they had greater freedom than the domestic press. In reality, however, they did not differ too much from the German newspapers (the historian Ivo Schöffer considered the DZN to be more Nazi than its sister paper, the Brussels newspaper ) , despite some rule violations with regard to “thrashing phrases and clichés” ( Oron J. Hale ). Accordingly, the general news section often consisted of front propaganda reports and other elements of Nazi propaganda, such as agitations against Bolshevism and an alleged world Jewry . A series of articles initially published in the Parisian sister newspaper, which was entitled “Jewish and Aryan Chess”, had a particular impact on a “Jewish lack of courage and creative power”. The world chess champion Alexander Alekhine , who later denied his authorship, traded as the author. However, the articles are very likely to be attributed to him and led to his discrediting after the war.

In contrast, the newspaper presented itself to the Dutch in a promotional tone, the aim here being to suggest a normality that would return under the new order. In areas such as culture and economic relations, references were made to real or propaganda-inspired links between the Netherlands and Germany. Dutch was often adjusted by the DZN in such a way that it should appear analogous to German, and developments within the country were interpreted as a shift towards German conditions. On the other hand, the editors included scraps of Dutch language in their articles to show that they had become at home in their new place of work.

The DZN was monitored by a number of control bodies: in The Hague by the press department of the Reich Commissariat under Willi Janke, in Berlin by the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda (RMVP) under Goebbels and the press policy office under Otto Dietrich . According to Amann, some of the editors of his occupation newspapers got into trouble by Goebbels and Dietrich's failure to comply with the regulations of the RMVP (which was later confirmed by several of his editors-in-chief at the time). The monitoring of the DZN did not always run smoothly due to occasional disregard of these requirements. For example, during a ministerial conference, RMVP functionary Hans Fritzsche reported the confiscation of an edition in Germany that had dealt with the taboo "Hess case" ( Rudolf Hess ' flight to Scotland ) and thereupon questioned the newspaper's loyalty. In addition, the DZN was often criticized for errors in reporting. Two of the five administrative fines pronounced against Dutch newspapers in the first eight months of 1942 were imposed on the DZN. However, according to Frotscher, a kind of preliminary editorial censorship had already been used in front of these supervisory bodies: the claim to argue as convincingly as possible in the articles had occasionally led to drafts only being approved after repeated objections.

Attitude to the independence of the Netherlands, Nederlandsche Unie and NSB

The newspaper took an ambiguous stance on the political collection movement Nederlandsche Unie , which was founded shortly after the DZN (subject to conditions with the approval of Seyß-Inquart) and campaigned for a united and independent Netherlands. Although the DZN the Unie derided as "devolved concentration," she did not contradict its objectives explicitly. Since the Netherlands was initially left formally independent (hope for a peace treaty with Great Britain , importance of the Dutch colonies ) and the Unie was viewed as a tool for the self-Nazification of the country, there was initially no reason to do so. However, with a “With us or against us!” In the newspaper, Seyss-Inquart demanded from the Dutch a commitment to support Germany.

Even after the Dutch National Socialists NSB, whose membership was many times weaker, had become the only permitted political party at the end of 1941 due to the Unie's refusal to support the attack on the Soviet Union , the newspaper did not give them any special preference, although the DZN saw itself as its protector . While the anti-annexionist wing under party leader Mussert was striving for National Socialist, but, like the Unie, independent Netherlands, the increasing influence of the SS within the power struggle between it, Seyß-Inquart and the NSDAP made it clear that "in due course" an integration into a " Greater Germanic Empire ”should take place regardless of public statements and a desired self-nazification.

Distribution and Readership

Although the DZN tried to attract Dutch readers, the majority of the circulation went to a German readership, so that there was only limited direct competition between the newspaper and the rest of the Dutch press. Since the occupation there could no longer be any question of an effect of supply and demand on the edition of the latter; With regard to the DZN, this was certainly not the case, as it had to fulfill a state-political mandate. Their position in relation to the rest of the domestic press was further strengthened by the fact that the administrative authorities of the occupied countries usually guaranteed Amann a purchase of 30,000–40,000 copies. In addition, the DZN was not only able to benefit from the advantages of paper rationing and the low subscription price. During the occupation, a number of Dutch newspapers were banned or forcibly merged, while others ceased to appear.

Notwithstanding all these advantages, the DZN was only able to establish itself to a modest extent within the Dutch press landscape. In the first few months, the newspaper did not get past its starting circulation of 30,000 copies. Based on this minimum value, the newspaper was in the middle of the field compared to the ten other national daily newspapers in the Netherlands at the end of 1940, but excluding the predominantly German reader share, it only occupied a marginal position. For May 1942, a print run of 54,500 copies was finally given, of which around 23,000 were sent directly to the Wehrmacht. Should it have maintained this value in the following year, the same situation would apply, as several other Dutch national daily newspapers also recorded significant increases in circulation between 1940 and 1943. In April 1945 the newspaper had around 35,000 copies.

The circulation area of the DZN was not limited to the Netherlands, Germany and other countries also received copies of the newspaper. Within the Netherlands, the DZN's sense of mission was not limited to the general population, it also saw itself as a guide for the rest of the press, and tried to demonstrate what a “real” newspaper should look like in journalistic terms under the new circumstances. This desired role model function went so far that articles of the DZN were recommended for reprint at the daily press conferences in The Hague. Since the (legal) Dutch press the since 1941 more and more increasing DC circuit had rather together despite sporadic oppose the whole, rather than risk a setting, but she could increasingly stand out from the DZN anyway. Outside of other editorial offices, their broader Dutch audience was in the business world, and their readership also included politically interested people and collaborators with the occupying power. Notice was also taken of the newspaper within the Dutch resistance, as evidenced by occasional mentions in the underground press.

In financial terms, the DZN was quite successful. According to Rienhardt, the occupation newspapers were not subsidized and were self-supporting after some initial help, and there was no shortage of advertisers at the DZN.

Actual influence of the DZN

Influence on the Dutch public

Due to the small number of initial copies of the DZN, most of which went to facilities of the occupying power, it was at least initially almost completely withdrawn from the general public. The later increase in circulation did not change the fact that the efforts of the DZN to influence the Dutch population with the copies from the free sale failed. The newspaper was rejected as a propaganda tool anyway, and the Dutch were already disappointed with their own press. Due to the insistence of the overwhelming majority of the NSB on an independent National Socialism, Christoph Sauer, who also examined the DZN linguistically , came to the conclusion that its members were probably also not among the readers of the newspaper (but this happened occasionally). There were few other reasons for them to resort to the DZN, as the NSB maintained a daily newspaper with the Nationale Dagblad and a weekly newspaper with Volk en Vaderland . Another sign of the low acceptance among NSB members is that Volk en Vaderland , which stood for the course of the party leadership, turned out to be far more successful than the Nationale Dagblad . In any case, the latter represented the völkisch-annexionist wing of the party until the dismissal of its editor-in-chief Meinoud Rost van Tonningen in October 1940, thus anticipating the later attitude of the occupiers, and thus also of the DZN.

The quickly emerging rejection on the part of the Dutch population did not prevent the German occupying power and the DZN from making assessments and assertions that were fundamentally at odds with reality, so Seyß-Inquart made an estimate in July 1940 in a situation report to Hitler that the DZN half would be sourced from the Dutch. Even after the February strike of 1941 had revealed the failure of the German advertising attempts, the newspaper went so far as to say "that the blood of a kindred is raising its voice louder and louder". The advertising efforts of the DZN and the German occupation authorities stood in a peculiar contradiction to the behavior of Hitler, who, after giving his instructions on how to set up the occupation administration, quickly lost interest in the Netherlands, which, by the way, he never visited during his life.

The DZN often attacked Great Britain with its reporting, but was unable to destroy the Dutch people's ideas and hopes associated with this country and instead generate greater sympathy for the Germans. In contrast to the actually targeted readership, however, the DZN and its sister newspapers were often more of interest to the allied British and American counter-intelligence than the domestic German press, as they were able to obtain valuable information about the actions and views of the occupation authorities scattered across Europe.

Comparison with other attempts at influence

A characteristic of the DZN's conceptual mistake is that other propaganda campaigns reached a much larger Dutch audience. The Active Propaganda Department of the Main Department for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda of the Reichskommissariat published De Gil, a satirical newspaper in 1944 , which was aimed specifically at the Dutch population and achieved high circulation during its short existence. The radio speeches by the aforementioned Max Blokzijl were also a crowd puller. In both cases, however, a high entertainment value played an essential role, and neither could they achieve a change of mood in favor of the occupying power. The German entertainment films, which served as distraction, were also popular, even after the audience was forced to watch the newsreels from 1943 onwards .

The DZN and the other instruments of the occupying power, however, embodied only the most undisguised and persistent efforts to influence public opinion in the Netherlands through the local press; Exposure tests, there were already before the First World War with the accommodation of articles, sat down to the German occupation by additional means such as bribery and journalists traveling on libel to massive pressure on the government to enforce censorship continued and were during the era of National Socialism by Punitive measures such as withdrawal of advertisements, ban / confiscation in Germany and expulsion of correspondents added.

The last year

When the liberation of the Netherlands seemed imminent at the beginning of September 1944 due to the rapid advance of the Allies (" Dolle Dinsdag ") , the majority of the editorial team tried to move to Germany, which led to a major personnel crisis. As a result, the then editor-in-chief E. C. Privat was immediately replaced, the newspaper continued to appear in the Netherlands, despite the increasingly dwindling southern, and later also eastern, distribution area until the German surrender. Since the rail strikes that began in the same month had restricted distribution channels, a separate Groningen edition was created at the end of October 1944 . For local editorial director was August Ramminger appointed to the Berlin editorial offices of DZN was previously chief. This edition was printed on the presses of the banned Nieuwsblad van het Noorden . Originally, the DZN wanted to rent his printing house, after this was rejected by the Nieuwsblad publishing house , it was unceremoniously confiscated in exchange for compensation.

Despite their privileged position, the cuts in supplies had become more and more visible in the newspaper; it was published without a Sunday edition since mid-July 1944, and the number of pages was noticeably reduced. In its format and scope, the DZN has recently increasingly resembled a leaflet and thus also the German Soldatenzeitung for the Netherlands and other attempts launched by resistance groups in the last days of the war to persuade the German soldiers to give up.

The penultimate edition of the DZN from May 4, 1945 still consisted of a full page. In addition to the last military reports, in particular the declaration of Flensburg as an open city , Albert Speer's speech was printed, which was broadcast on May 3rd by the Reichsender Flensburg . The last edition of the newspaper was just a hectograph , which contained an official German declaration on a DIN A5 sheet that the troops in Holland had not surrendered. But the process of surrender could no longer be stopped. May 5, 1945 went down in the history of the Netherlands as the day of liberation .

The end of the newspaper ultimately also marked the end of a German-language press in the Netherlands . Most of the documents on the DZN were lost in the fire. In order to settle claims, the publisher was placed under an administrator for a while before it was dissolved.

Employee of the DZN after the war

Of the four successive editors-in-chief, Emil Frotscher , who was most recently responsible for the Eastern newspapers in Rienhardt's administrative office, was most prominent in the post-war period. For many years he was editor-in-chief of the national tabloid Abendpost , which was assigned a special position in Germany, and was then responsible for the “Series and Biographies” section at Welt am Sonntag . One of his successors, Emil Constantin Privat, worked in the Federal Government's Press and Information Office and was President of the German Huguenot Association from 1950 to 1971 . His replacement, Antonius Friedrich Eickhoff, took over the editor-in-chief of the Westfälische Nachrichten . Frotscher's direct successor Hermann Ginzel went to the Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger .

Wilhelm Muhrmann , head of the DZN service from 1941 to 1945 , worked after the war not only as a journalist but also as an author of crime and entertainment novels and as the district manager of the FDP . The head of the Groninger edition, August Ramminger , joined the CSU and was a member of the German Bundestag from 1961 to 1965 , he was also deputy editor-in-chief of the Passauer Neue Presse .

List of publishing directors and editors-in-chief

| Publishing Director | |

| Georg Biedermann | 1940-1945 |

| Editors-in-chief | |

| Emil Frotscher | 1940 |

| Hermann Ginzel | 1940-1941 |

| Emil Constantin Private | 1941-1944 |

| Antonius Friedrich Eickhoff | 1944-1945 |

literature

- Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: Organization and control of journalism . Verlag Documentation Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5th excursus: The German newspaper in the Netherlands , pp. 78–93), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X . Dissertation Munich 1972.

- Christoph Sauer:

- The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , pp. 198-200.

- The intrusive text: Language policy and Nazi ideology in the "Deutsche Zeitung in the Netherlands" . Springer, Berlin 2013, ISBN 3-8244-4285-X (first published by Deutsches Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden 1998. Dissertation Amsterdam 1990) (Sauer's statement that subscribers to the German weekly newspaper for the Netherlands were (presumably) taken over by the DZN (p . 261), on the other hand, the German weekly newspaper continued to appear in the Netherlands until 1942).

- Nazi German for Dutch people. The concept of Nazi language policy in the "Deutsche Zeitung in the Netherlands" 1940–1945 . In: Konrad Ehlich (Ed.): Language in Fascism . 3rd edition, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1995 (= Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft; 760), ISBN 3-518-28360-X , pp. 237–288.

Web links

- All editions in digitized form ( Royal Library of the Netherlands , service in Dutch)

- Literature from and about Deutsche Zeitung in the Netherlands in the catalog of the German National Library

- The DZN in the catalog of the Royal Dutch Library (Dutch)

Individual evidence

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 63. Dissertation Leiden 1988. Weekly publication after the entry of the Reichsdeutsche Nachrichten in the catalog of the German National Library, cf. also German newspaper for the Netherlands. [ sic ] In: Zeitungswissenschaft (Vol. 15), Issue 5/6, 1940, p. 248.

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , pp. 62 and 468 (Dissertation Leiden 1988). The statement made in a paper by Katja Happe that the DZN was a merger of these two newspapers is at least incorrect for the time the DZN was founded, cf. also the entry for the newspaper in the catalog of the German National Library ( Katja Happe: Germans in the Netherlands 1918–1945 , published on the Internet by the library of the University of Siegen in December 2004 ( PDF ), p. 112).

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , pp. 228 and 234. Dissertation Leiden 1988. U- turn of the Telegraaf after Paul Stoop: Dutch press under pressure. German foreign press policy and the Netherlands 1933–1940 . Saur, Munich 1987 (= communication and politics; 17), ISBN 3-598-20547-3 , p. 90, footnote 24. Dissertation Amsterdam.

- ^ Paul Hoser: Franz Eher Nachf. Verlag (central publishing house of the NSDAP) . In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns Exact description by Oron J. Hale : Press in the straitjacket 1933-45. Droste, Düsseldorf 1965, German translation of The captive press in the Third Reich , University Press, Princeton 1964, pp. 280 and 340 as well as by Thomas Tavernaro: Der Verlag Hitlers und der NSDAP. The Franz Eher Successor GmbH. Edition Praesens, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-7069-0220-6 , pp. 74-75. Europa-Verlag was renaming the Rheinische Verlagsanstalt, which previously existed as an empty shell company (Tavernaro, p. 75).

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 87, footnote 152. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 80. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ↑ a b Christoph Sauer: The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , p. 198.

- ↑ The book is called The Netherlands Economy and its Relationships with Germany and the World ( entry in the Karlsruhe Virtual Catalog ). Offers for theater of war maps can be found, for example, in the following issues: July 27, 1943 (Eastern Front Map), September 12, 1943 (Map of Europe), 27./28. May 1944 (Pacific Map) ( Digital Archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ). Possible print jobs according to Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 89. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ↑ Louis de Jong : The German Fifth Column in World War II . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1959 (German edition by De Duitse Vijfde Colonne in de Tweede Wereldoorlog . Van Loghum Slaterus / JM Meulenhoff, Arnheim / Amsterdam 1953 (dissertation Amsterdam 1953). Online edition ( PDF )), p. 183.

- ^ Gerhard Hirschfeld : Foreign rule and collaboration. The Netherlands under German occupation 1940–1945 . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1984 (= studies on contemporary history; 25), ISBN 3-421-06192-0 , p. 14. Dissertation Düsseldorf 1980.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , no provincial or homeland sheet: p. 78, footnote 119, specifications: p. 81–83. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ↑ Branches and number of editors according to Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , pp. 84 and 87 (dissertation Munich 1972). Origin of the editors according to Christoph Sauer: The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , p. 199.

- ↑ Christoph Sauer: The intrusive text: Language policy and Nazi ideology in the "Deutsche Zeitung in the Netherlands" . Springer, Berlin 2013, ISBN 3-8244-4285-X (first published by Deutsches Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden 1998. Dissertation Amsterdam 1990), pp. 272–273.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 87 (dissertation Munich 1972) and Andreas Laska: Presse et propaganda en France occupée: des Moniteurs officiels (1870 –1871) à la Gazette des Ardennes (1914–1918) et à la Pariser Zeitung (1940–1944). Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-8316-0293-X , p. 258 (dissertation in the “Cotutelle procedure” Munich 2003).

- ↑ Federal Archives / Institute for Contemporary History / Chair for Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Freiburg / Chair for the History of East Central Europe at the East European Institute of the Free University of Berlin (ed.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 . Volume 5, Western and Northern Europe 1940– June 1942 , edited by Michael Mayer, Katja Happe, Maja Peers, R. Oldenbourg, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58682-4 , pp. 284–285, footnote 2 After his time at the DZN, Ginzel was a correspondent for the WB in Paris, and according to a journalist he was ultimately deputy editor-in-chief of the newspaper (Institute for Newspaper Studies at the University of Berlin (ed.): Handbuch der Deutschen Tagespresse. Armanen- Verlag, Leipzig 1944 (7th edition), p. 78 (correspondent in Paris) and Manfred Pohl : M. DuMont Schauberg. The struggle for the independence of newspaper publishers under the Nazi dictatorship. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-593-38919-6 , p. 261 (deputy chief editor)).

- ^ A b c d Christoph Sauer: The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , p. 199.

- ^ Emil Frotscher: Balance of a young newspaper. Four months “German newspaper in the Netherlands”. In: Zeitungs-Verlag (vol. 41), edition 42, October 19, 1940, p. 361 ff., Quoted from Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 80. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 80 (dissertation Munich 1972) and René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , pp. 238-239 (Dissertation Leiden 1988).

- ^ Huub Wijfjes: Journalistiek in Nederland 1850–2000. Beroep, cultuur en organisatie. Boom, Amsterdam 2004, ISBN 90-5352-949-7 , pp. 246-248.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 84, footnote 141. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ↑ February 16, 1941: Meeting point at the Reichsmesse City Leipzig, March 16, 1941: Jaarbeurs Utrecht, May 8–15. June 1941: 1 year DZN, August 29th / 3rd September 1941: Leipziger Messe, 9./12. September 1941: Jaarbeurs Utrecht ( Digital Archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ). In 1942, however, there could not have been any special editions for the fairs, as these were canceled (in the case of the Jaarbeurs by order of the Reich Commissioner, Utrechte Jaarbeurs gaat niet door. In: Utrechts Nieuwsblad , February 16, 1942, p. 2 and Utrecht tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog (1940–1945) ( Memento from May 17, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) , City of Utrecht archive).

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 323 (Dissertation Leiden 1988) and Gerhard Hirschfeld foreign rule and collaboration. The Netherlands under German occupation 1940–1945 . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1984 (= studies on contemporary history; 25), ISBN 3-421-06192-0 , p. 80 (dissertation Düsseldorf 1980).

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 295 and p. 538, footnote 53 (values for 1943, for the DZN about 8.5%). Dissertation Leiden 1988.

- ↑ The monthly or quarterly price of the DZN of 1.40 / 4.20 guilders given in the newspaper header compared to the quarterly prices of the national Dutch daily newspapers given by René Vos (René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legal Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 336 (Dissertation Leiden 1988) and digital archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ).

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 334. Dissertation Leiden 1988.

- ^ A b c Christoph Sauer: The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , p. 200.

- ^ A b Emil Frotscher: Balance of a young newspaper. Four months “German newspaper in the Netherlands”. In: Zeitungs-Verlag, (vol. 41), edition 42, October 19, 1940, p. 361 ff., Quoted from Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , pp. 85–86. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ Christoph Sauer: The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , p. 200 and Otto Thomae: Die Propaganda-Maschinerie. Fine arts a. Public relations in the Third Reich. Mann, Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-7861-1159-6 , pp. 183-185. Dissertation Berlin 1976.

- ↑ Katja Happe: Germans in the Netherlands 1918–1945 , published on the Internet by the library of the University of Siegen in December 2004 ( PDF ), p. 112.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 88. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ A b Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: Organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , pp. 84–85. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ Christoph Sauer: The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , p. 200. The serial novels and stories are summarized by him as novels.

- ↑ Henk Nijkeuter: Drent uit Heimwee en require . Van Gorcum, Assen 1996, ISBN 90-232-3175-9 , p. 65.

- ^ Speeches by Hitler and Goebbels after Christoph Sauer: The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , p. 200. Calls by Göring can be found, for example, on the occasion of Hitler's birthdays in the April 20, 1943 and 1944 editions. Interview with Seyß-Inquart according to PA Donker: Winter '44 -'45. A winter that is never forgotten . Ad. Donker, Bilthoven / Antwerp 1945, p. 16.

- ↑ "Building bridges" is the name of the paper's new task. In: Zeitungs-Verlag (vol. 41), edition 24, June 15, 1940, p. 203. The articles mentioned can be found in the first edition of the DZN from June 5, 1940, Osendarp starts in Amsterdam , p. 7 and expansion of the Economic Relations , p. 11 ( Digital Archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ).

-

^ Max Blokzijl : Rembrandt Day 1944. In: DZN, July 14, 1944, page 1 ( digital archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ).

Ben van Eysselsteijn: Utrecht - The heart of the Netherlands. In: DZN, September 3, 1940, p. 5 and theater as a folk task. In: DZN, December 16, 1940, p. 7 ( digital archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ). However, according to van Eysselsteijn, these articles had already appeared before and were published in the newspaper without his consent (Henk Nijkeuter: Drent uit heimwee en require. Van Gorcum, Assen 1996, ISBN 90-232-3175-9 , p. 65).

Jonny Heykens: Entry about him in the Poparchief Groningen , last accessed March 30, 2015 and The whole world envies you. In: DZN, May 12, 1941, p. 2. - ↑ Heinz-Werner Eckhardt: The front newspapers of the German army 1939-1945 . Wilhelm Braumüller Universitäts-Verlagsbuchhandlung, Vienna / Stuttgart 1975 (= series of publications by the Institute for Journalism at the University of Vienna; 1), p. 8.

- ↑ Henk Nijkeuter: Drent uit Heimwee en require . Van Gorcum, Assen 1996, ISBN 90-232-3175-9 , p. 65.

- ↑ Henk Nijkeuter: Drent uit Heimwee en require . Van Gorcum, Assen 1996, ISBN 90-232-3175-9 , pp. 65 and 129.

- ↑ Emigrant work in Amsterdam. In: DZN , October 27, 1940, p. 5.

- ↑ Oron J. Hale : Press in the straitjacket 1933-45. Droste, Düsseldorf 1965, German translation of The captive press in the Third Reich , University Press, Princeton 1964, p. 281 and Ivo Schöffer : Het nationaal-socialistische beeld van de geschiedenis der Nederlanden. A historiographical and bibliographical study . New edition by Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-5356-895-6 , p. 273 (originally published by Van Loghem Slaterus, Arnheim / Amsterdam 1956. Dissertation Amsterdam 1956). dbnl.org , alternatively (PDF).

- ↑ Ralf Woelk: Chess under the swastika . Promos-Verlag, Pfullingen 1996, ISBN 3-88502-017-3 , pp. 101-105, see also the article Chess Notes No. 3605, 3606, 3617 , last accessed March 30, 2015. The articles appeared in the DZN on March 23 and 28 and April 2, 1941. The series later appeared in the Deutsche Schachzeitung .

- ↑ Oron J. Hale : Press in the straitjacket 1933-45. Droste, Düsseldorf 1965, German translation of The captive press in the Third Reich , University Press, Princeton 1964, p. 281 and Heinz-Werner Eckhardt: Die Frontzeitungen des Deutschen Heeres 1939–1945 . Wilhelm Braumüller Universitäts-Verlagsbuchhandlung, Vienna / Stuttgart 1975 (= series of publications by the Institute for Journalism at the University of Vienna; 1), p. 8.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , pp. 90–91. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ↑ From whom (NSDAP or SS) is unclear according to Hoffmann (Gabriele Hoffmann: NS-Propaganda in the Netherlands: Organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= Kommunikation und Politik; 5), ISBN 3-7940 -4021-X , p. 90. Dissertation Munich 1972).

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 218. Dissertation Leiden 1988.

- ^ Wichert ten Have: De Nederlandse Unie. Adapting, vernieuwing en confrontatie in bezettingstijd 1940–1941 . Prometheus, Amsterdam 1999, ISBN 90-5333-875-6 , p. 241 (Dissertation Amsterdam 1999). See also The Echo of the Day. In: DZN, July 9, 1940, page 6: “The program has since been published. We don't want to comment on this either ... "

- ^ Gerhard Hirschfeld : Foreign rule and collaboration. The Netherlands under German occupation 1940–1945 . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1984 (= studies on contemporary history; 25), ISBN 3-421-06192-0 , pp. 22–38 and 45–59. Dissertation Düsseldorf 1980.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 251. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ Non-preferential treatment of NSB according to Christoph Sauer: The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , p. 199, DZN as protector of the NSB according to Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 90. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ Gerhard Hirschfeld : Foreign rule and collaboration. The Netherlands under German occupation 1940–1945 . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1984 (= studies on contemporary history; 25), ISBN 3-421-06192-0 , p. 22 ff, especially p. 32–35 (dissertation Düsseldorf 1980) and René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 453 (Dissertation Leiden 1988).

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 323. Dissertation Leiden 1988.

- ↑ Oron J. Hale : Press in the straitjacket 1933-45. Droste, Düsseldorf 1965, German translation of The captive press in the Third Reich , University Press, Princeton 1964, p. 280.

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 323 (Dissertation Leiden 1988) and Gerhard Hirschfeld : Foreign rule and collaboration. The Netherlands under German occupation 1940–1945 . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1984 (= studies on contemporary history; 25), ISBN 3-421-06192-0 , p. 80 (dissertation Düsseldorf 1980).

- ^ A b Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: Organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 91. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ↑ Minimum value of 30,000 copies compared to the numbers given by Jan van de Plasse for the national Dutch-language daily newspapers in the country in December 1940 (Jan van de Plasse: Kroniek van de Nederlandse Tagblatt- en opiniepers / samengesteld door Jan van de Plasse. Red. Wim Verbei . Otto Cramwinckel Uitgever, Amsterdam 2005, ISBN 90-75727-77-1 , p. 194).

- ^ Edition according to Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi Propaganda in the Netherlands: Organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 89 (dissertation Munich 1972). Number of copies delivered to the Wehrmacht services after Christoph Sauer: The intrusive text: Language policy and Nazi ideology in the "Deutsche Zeitung in the Netherlands" . Springer, Berlin 2013, ISBN 3-8244-4285-X (first published by Deutsches Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden 1998. Dissertation Amsterdam 1990), p. 277, footnote 125.

- ↑ Jan van de Plasse: Kroniek van de Nederlandse dagblad- en opiniepers / seed gesteld by Jan van de Plasse. Red. Wim Verbei . Otto Cramwinckel Uitgever, Amsterdam 2005, ISBN 90-75727-77-1 , p. 194, based on the information for July 1943.

- ↑ Christoph Sauer: The intrusive text: Language policy and Nazi ideology in the "Deutsche Zeitung in the Netherlands" . Springer, Berlin 2013, ISBN 3-8244-4285-X (first published by Deutsches Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden 1998. Dissertation Amsterdam 1990), p. 277, footnote 125.

- ^ Christoph Sauer: The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , pp. 198-199.

- ↑ For a list of the illegal press, cf. Lydia E. Winkel: De Ondergrondse Pers 1940–1945 . Rijksinstituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie, Amsterdam 1989, ISBN 90-218-3746-3 , pp. 98 and 145, originally published by Veen, The Hague 1954. Online edition (PDF) under CC-BY-SA 3.0 license ( PDF ). On resistance within the legal press, cf. René Kok: Max Blokzijl: Stem van het nationaal-socialisme . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-0231-7 , p. 57 (keeping press guard Max Blokzijl away from the De Standaard newspaper ), Guus Pikkemaat: Dagblad De Gooi- en Eemlander tijdens de oorlogsdagen, de bezettingstijd en de eerste jaren na de bevrijding (1940-1950) . Dagblad Gooi- en Eemlander, Hilversum 1991, p. 27 (Pikkemaat describes the sabotage of forced articles there) and Jan van de Plasse: Kroniek van de Nederlandse dagblad- en opiniepers / samengesteld door Jan van de Plasse. Red. Wim Verbei . Otto Cramwinckel Uitgever, Amsterdam 2005, ISBN 90-75727-77-1 , p. 70 (Voluntary employment of the Friesch Dagblad because the journalists did not want the Verbond van Nederlandsche Journalisten to oblige them). Harmonization and continuation of the work according to René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , pp. 571-574. Dissertation Leiden 1988.

- ↑ Examples are De Vonk , January 20, 1941, p. 7, De vrije katheder. Bulletin ter verdediging van de universiteiten. , December 11, 1943, p. 4 and Trouw. Speciale uitgave voor Rotterdam en omstreken. , March 14, 1945, p. 2 ( Digital Archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ). Carel Enkelaar, who worked for the underground newspaper Het Parool at the time, also confirmed that the DZN had been evaluated ( Die Nacht waar ik het Dichtst bij de oorlog. In: De Telegraaf , November 24, 1984, p. 93) ( Digital archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ).

- ↑ Heinz-Werner Eckhardt: The front newspapers of the German army 1939-1945 . Wilhelm Braumüller Universitäts-Verlagsbuchhandlung, Vienna / Stuttgart 1975 (= series of publications by the Institute for Journalism at the University of Vienna; 1), ISBN 3-7003-0080-8 , p. 7.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 89, footnote 171. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 91. Dissertation Munich 1972.

-

↑ In Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog (Part 6 (July 1942 to May 1943), Volume 1, p. 381) the sales figures of an Amsterdam NSB shop for May 1941 are listed as an example, the DZN (19 copies) is clearly indicated behind the Reich (67) and above all behind the lavish foreign magazine Signal (860). Sales were also well behind the NSB newspapers Volk en Vaderland (208, back 257) and Het Nationale Dagblad (143, back 232), but ahead of the striker (4, back 16) and the Völkischer Beobachter (no sales).

The following newspaper articles report about one NSB subscriber to the DZN: Tribunaal, Heerenveen . In: Leeuwarder Koerier , March 6, 1946, p. 2 and Tribunaal Leeuwarden. In: De Heerenveensche Koerier , 13 September 1946, p. 2 ( digital archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ). - ^ Christoph Sauer: The German newspaper in the Netherlands. In: Markku Moilanen, Liisa Tiittula (editor): Persuasion in the press: texts, strategies, analyzes . De Gruyter, Berlin 1994, ISBN 978-3-11-014346-1 , p. 199.

- ^ Völkisch-annexionist wing after Gerhard Hirschfeld : Foreign rule and collaboration. The Netherlands under German occupation 1940–1945 . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1984 (= studies on contemporary history; 25), ISBN 3-421-06192-0 , p. 164 (dissertation Düsseldorf 1980). Dismissal of Rost van Tonningen after René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 105 (Dissertation Leiden 1988). Circulation numbers according to Vos, p. 469 and Jan van de Plasse: Kroniek van de Nederlandse dagblad- en opiniepers / samengesteld door Jan van de Plasse. Red. Wim Verbei . Otto Cramwinckel Uitgever, Amsterdam 2005, ISBN 90-75727-77-1 , p. 290.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 84 (dissertation Munich 1972). The “ss” became a “ß” in the work, although the DZN did not use the character at all due to the fact that it was printed in the Netherlands (the article in question “After a year” is on the title page of the anniversary edition from 5 June 1941 ( Digital Archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands )).

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 27. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 83 (dissertation Munich 1972) and Peter Köpf : Writing in any direction. Goebbels propagandists in the West German post-war press. Ch. Links, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-86153-094-5 , pp. 108-109 and 159-160.

- ↑ Oron J. Hale : Press in the straitjacket 1933-45. Droste, Düsseldorf 1965, German translation of The captive press in the Third Reich , University Press, Princeton 1964, p. 281.

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , pp. 367-368. Dissertation Leiden 1988.

- ^ René Kok: Max Blokzijl: Stem van het nationaal-socialisme . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-0231-7 , p. 106.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 245 and footnote 147. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ Paul Stoop: Dutch press under pressure. German foreign press policy and the Netherlands 1933–1940 . Saur, Munich 1987 (= communication and politics; 17), ISBN 3-598-20547-3 (dissertation Amsterdam), placement of articles: pp. 22–24, 27–29, 31 and 260–300, bribery: pp. 27 and 34, journeys to journalists: pp. 242–248, complaints of libel: pp. 102 and 110–111, pressure on the government to enforce censorship: pp. 103–125, withdrawal of advertisements: pp. 208–209 and 218–232 Prohibition: Pp. 202–205, confiscation: pp. 205–207, expulsion of correspondents: pp. 333–341.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , pp. 88 and 92–93. Dissertation Munich 1972.

- ^ René Vos: Niet voor publicatie. De legale Nederlandse pers tijdens de Duitse bezetting . Sijthoff, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-218-3752-8 , p. 387. Dissertation Leiden 1988.

- ↑ In its edition of July 15, 1944, the DZN reported on the second page that the newspaper was temporarily foregoing the Sunday edition for reasons of time; the old publication was not resumed ( digital archive of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ).

- ↑ Lydia E. Winkel: De Ondergrondse Pers 1940-1945 . Rijksinstituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie, Amsterdam 1989, ISBN 90-218-3746-3 (originally published by Veen, The Hague 1954). Online edition ( PDF ) under CC-BY-SA 3.0 license . German-language resistance publications of the last few days are listed there at the following place: German Soldier Newspaper for the Netherlands p. 98 and 145, Free Press - German edition for the Wehrmacht p. 105, Die LETZTE CHANCE! Organ of the German Resistance Movement p. 144, News for the Troops p. 158 and Soldiers Mail for Holland p. 227. Digitized editions of the Soldatenzeitung for the Netherlands have been made available by the Royal Library of the Netherlands . For comparison, see the last editions of the DZN.

- ↑ Deutsche Zeitung in the Netherlands of May 4, 1945 , accessed March 18, 2018, and Gerhard Paul : "Since midnight the guns have been silent on all fronts." The "Reichssender Flensburg" in May 1945. In: Gerhard Paul, Broder Schwensen (Ed.): May '45. End of the war in Flensburg (= publication series of the Society for Flensburg City History). 1st edition. Volume 80. Society for Flensburg City History, Flensburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-925856-75-4 , page 70 f.

- ^ Gabriele Hoffmann: Nazi propaganda in the Netherlands: organization and control of journalism . Saur, Munich-Pullach / Berlin 1972 (= communication and politics; 5), ISBN 3-7940-4021-X , p. 93 (dissertation Munich 1972). For the content, see the illustration opposite. Jan van de Plasse incorrectly names May 2, 1945 as the last publication date (Jan van de Plasse: Kroniek van de Nederlandse dagblad- en opiniepers / samengesteld door Jan van de Plasse. Red. Wim Verbei . Otto Cramwinckel Uitgever, Amsterdam 2005, ISBN 90 -75727-77-1 , p. 76).

- ↑ Christoph Sauer: The intrusive text: Language policy and Nazi ideology in the "Deutsche Zeitung in the Netherlands" . Springer, Berlin 2013, ISBN 3-8244-4285-X , p. 271, footnote 123 (first published by Deutsches Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden 1998. Dissertation Amsterdam 1990).

- ↑ A call to file such claims as soon as possible can be found in the Tijd of October 22, 1945 on the second page. There was also an appeal to help locate three stolen vehicles from the publisher's fleet ( De Waarheid , November 15, 1945, p. 4) ( Digital Archives of the Royal Library of the Netherlands ).

- ^ Evening post after Kurt Pritzkoleit : Who owns Germany . Kurt Desch publishing house, Vienna / Munich / Basel 1957, pp. 215–216. Dead from the ticker . In: Der Spiegel . No. 18 , 1966, p. 62 ( online ). Ostzeitungen according to Peter H. Blaschke / Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation (ed.): Journalist under Goebbels. A father study based on the files . Wallstein, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8353-0437-6 , p. 103.World on Sunday : Imprint of the world on Sunday of February 18, 1968 (p. 7). The aforementioned documents, which only refer to individual stations of Frotscher, support the published memories of the historian Hans Preuschoff, who gives an overview of Frotscher's professional career (Zeitschrift für die Geschichte und Altertumskunde Ermlands, Supplement 6: Hans Preuschoff. Journalist in the Third Reich , self-published by the Historisches Verein für Ermland , Münster 1987, pp. 60–63).

-

↑ Press and Information Office of the Federal Government according to Politique étrangère , Edition 5 from 1956, p. 661. German Huguenot Association according to Jochen Desel, Walter Mogk (Ed.): 100 years of the German Huguenot Association. 1890-1990. History-persons-documents-pictures. Conference publication for the 36th German Huguenot Day from April 20-22, 1990 in Friedrichsdorf / Taunus. Publishing house of the German Huguenot Association e. V. 1890, Bad Karlshafen 1990, ISBN 3-9802515-0-0 , p. 280 (His biography on pages 260–262 is, however, embellished and conceals the time at the DZN and his escape). See also Die Huguenots in Germany - Thoughts on a work by Helmut Erbe. In: DZN, May 25, 1941, p. 10 (E. C. Privat wrote there as later chairman of the German Huguenot Association of "France, which was culturally very highly developed at that time"), Leder im Spiegel der Zeit. In: DZN, October 6, 1941, p. 3 and Klaus Späne: Villa des Leder-Fürsten . In: Taunus-Zeitung ( Frankfurter Neue Presse ), September 5, 2011.

In the DZN as well as in the literature on this newspaper, Emil Constantin Privat only ever appears with his abbreviation EC Privat, through the aforementioned documents, in particular through the two listed Article written by himself in the DZN, however, can be assigned to the newspaper beyond doubt. -

^ Heinz-Dietrich Fischer : Political parties and the press in Germany since 1945 . Schünemann, Bremen 1971 (= Studies on Journalism, Volume 15), ISBN 3-7961-3019-4 , p. 133, footnote 60.

In the DZN it was always only used under the abbreviation Dr. A. Fr. Eickhoff, then mostly as Dr. Antonius Eickhoff. The full name of Dr. Antonius Friedrich Eickhoff can be found in the association magazine Deutsche Presse by announcing his inclusion in the Association of the Rheinisch-Westfälische Presse - Press Association Münster (vol. 22, issue 15, April 30, 1932, p. 178). - ↑ Federal Archives / Institute for Contemporary History / Chair for Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Freiburg / Chair for the History of East Central Europe at the East European Institute of the Free University of Berlin (ed.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945 . Volume 5, Western and Northern Europe 1940– June 1942 , edited by Michael Mayer, Katja Happe, Maja Peers, R. Oldenbourg, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-486-58682-4 , pp. 284–285, footnote 2 .

- ^ Wilhelm Muhrmann in the Lexicon of Westphalian Authors , accessed May 23, 2011.

- ↑ Rudolf Vierhaus , Ludolf Herbst (ed.), Bruno Jahn (collaborator): Biographical manual of the members of the German Bundestag. 1949-2002. Vol. 2: N-Z. Attachment. KG Saur, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-598-23782-0 , p. 665.