Eugene Onegin

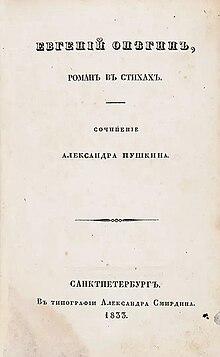

Eugene Onegin ( Russian Евгений Онегин , transcription : Evgeni Onegin , [ jɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj ɐˈnʲeɡʲɪn ]) is a verse novel by the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin . Pushkin wrote the verse epic between 1823 and 1830 and gave it the generic name Roman in Verse . The complete version of the work was first published in 1833.

The novel is about the complex cultural situation in Russia around 1820, portrayed in the life and thinking of young aristocrats in the metropolises of St. Petersburg and Moscow and on their country estates far away from the cities in the country, which has been arrested by old traditions. Eugene Onegin is considered the modern Russian national epic .

content

Eugene Onegin, just twenty years old and without parents, the only son of a nobleman who made his fortune with balls and amusements, leads the life of a dandy in St. Petersburg . When he inherits his uncle's fortune, tired of the Petersburg “ monde ” , he retires to the inherited estate in the province. He leases the lands to his serfs out of convenience and to the annoyance of his neighbors . He goes swimming, hikes, reads, plays billiards, draws caricatures, drinks champagne and otherwise lives like a hermit who avoids all contact with the neighborhood.

When he meets the young poet Wladimir Lensky, who has just returned to Russia from Göttingen, where he studied Kant, Schiller and Goethe, he becomes friends with him. The two spend a lot of time together. Lensky introduces him to the house of his fiancée Olga Larina, who lives there with her mother and sister Tatiana. The Larins live the old Russian way, cultivating old customs, old songs and old superstitions. The quiet and dreamy Tatiana feels drawn to the urbane and eloquent Onegin. Tatjana reads a lot, she dreams of the fictional world of a Richardson , Melmoth or Lord Byron , and Onegin lends her books. Onegin assesses Tatiana with the practiced look of a charmer , but Tatiana falls in love with the young man. In a passionate letter, she confesses her love to Onegin, which she regards as fateful. In him she recognizes her God-sent protector. Onegin interprets the letter as a marriage proposal, does not answer it and rejects it with cool words at the next opportunity. He dismisses her love as a girlish crush, has a bad opinion about marriage and family, he has left the phases of being in love behind, and he feels that he is not made for marriage. Tatiana will soon forget him and take someone more worthy than him as her husband. The local gossip, however, now sees Onegin and Tatiana as a future couple.

Two weeks before Lensky's marriage to Olga, Tatjana celebrates her name day . Lensky invites Onegin to the celebration, which he says takes place in close family circles. Instead, he finds himself in a noisy dance that he sees as a parody of the Petersburg balls. Tatyana's confusion, which can hardly hold back tears at the sight of him, annoys him in memory of his many love affairs that ended in Petersburg, and he is annoyed that the guests gossip about him and Tatiana. There had also been differences of opinion between Lensky and Onegin. Onegin refused to read Lensky's poetry and had his doubts about his muse Olga, whom he considers superficial and flirtatious. He decides to take revenge on Lensky who put him in this situation. He invites Olga to dance, flirts with her, dances one dance after the other with Olga, who is visibly flattered and does not notice how she hurt her fiancé. When Onegin notices from Lensky's reaction that his revenge has been successful, he loses all interest in Olga and leaves the house, where a disturbed Tatiana, who cannot figure out his behavior, remains.

Lensky challenges Onegin to a duel through a middleman . Although Onegin tries to present the whole thing as a misunderstanding and to avoid the duel, the middleman points out that he is violating social conventions and making himself look ridiculous. At first Onegin accepts the invitation indifferently, but then considers the unflattering role he played here and how easily he could have reconciled his friend. In the duel, however, he fires the first shot in cold blood and fatally hits Lensky.

After the duel, Onegin is tormented by remorse and leaves his estate with an unknown destination. Tatjana regularly visits his house, reads his books and tries to track down Onegin's character and essence through his notes and reading marks. Lensky is mourned by Olga for a while, but she soon consoles herself with an officer who is transferred to the provinces after the marriage. Tatjana remains alone with her mother. She fends off every applicant for her hand without justification. When her aunt visits Moscow, she is introduced to society, married to an elderly general, and becomes a perfect society lady.

The years go by. Onegin - now 26 years old, still bored and weary of society, bored of his restless travel life, an idler with no aim in life - returns to St. Petersburg. At a ball his gaze falls on Tatiana, whom he hardly recognizes. When they meet Tatiana remains distant, calm and self-assured, while the sight of Tatiana leaves Onegin speechless and he loses his composure.

In love as a boy, he follows her everywhere, writes unanswered letters and consumes himself in unrequited love.

When he finally succeeds in speaking to her alone, she reminds him of the time in the country, when he gave her a “sermon” and rejected her, just when a common happiness seemed so close at hand. She confesses to him that she would exchange all the glamorous life she leads in St. Petersburg for her old life in the country, in nature and with her books. She admits that she still loves Onegin, but she will not leave her husband, to whom she has sworn allegiance.

The story ends neither as a comedy with the happy union of the two main characters nor as a tragedy with their death, but it has an open ending, the further fate of the hero remains unknown.

Form

The verse novel is divided into eight chapters ( cantos ), each of which is preceded by a short quote from French, Italian or ancient literature or from a Russian author. The poem has a total of 384 stanzas. The so-called Onegin stanza is based on the sonnet . The stanza of 14 lines in four - footed iamb follows a complicated and strict rhyme scheme that is adhered to throughout the poem, with the exception of Tatyana's and Onegin's letters, as well as Tatiana's dream:

- [a B a B c c D D e F F e G G]

The small letters denote feminine rhymes , the capital letters denote masculine rhymes .

The final edition also contains a foreword by Pushkin and around 18 more or less completed stanzas about Onegin's travels.

The novel is told from the perspective of an authorial narrator , a “friend and brother” of Onegin. Pushkin's sketch "Self-portrait with Onegin on the banks of the Neva" was made before the first chapter was printed in St. Petersburg, and Reinhard Lauer interprets it as a "visual realization of the overall artistic structure of the novel. The moderating author and his problematic hero were equal instances in the verse novel who knew each other ”.

As with Sterne or Diderot , the narrator ironically accompanies and interprets the actions of his characters, addresses the fictional reader, argues with him and repeatedly strays from the thread of the narrative. He indulges in all sorts of excursions on the most varied of topics, the fine Russian society and its conventions, literature in general and French in particular, the problems with the deficits of the Russian language when writing his novel to his eulogies that border on fetishism on the beauty of the female foot. Whole poems and lyrical descriptions of nature are inserted into the text. The novel is full of quotes and references from Russian authors, European philosophers and writers and full of allusions to current Russian politics, which even Nabokov did not decipher all in his two-volume commentary on the novel.

The language

With his complete works and especially with Eugene Onegin, Pushkin is considered the founder of the Russian literary language. Around 1820, the lingua franca of the Russian upper class was French, official and scientific texts were usually written in French, ecclesiastical and secular Russian texts until the early 19th century in Church Slavonic , which was no longer generally understandable by Pushkin's time. Children of the nobility, such as Pushkin and Onegin themselves, as well as Tatjana and Olga Larina, had French educators or language teachers. Pushkin learned Russian from his nanny and perfected it in dealing with the rural population during his exile.

Pushkin's poems had already caught the attention of the Russian poet Gavriil Derschawin during his school days , who recognized Pushkin's poetry with a new tone, a new understanding of the Russian language and a poetic genius. Pushkin put a monument to him in the last chapter of his Eugene Onegin:

The applause met me happily.

The young prize won by

Derschawin gave me his blessing.

The grave-weary poet.

- Pushkin. Eugene Onegin. Chapter 8, verse 1.

According to the Russian literary scholar Vladimir Jelistratow, Pushkin made surgical interventions in the language, dispensed with all superfluous archaisms and cleaned up on a large scale. The Russian literary language, in which the great Russian novels of the 19th century were written , has existed since Pushkin .

Interpretations

Pushkin's poem was recognized early on by authoritative literary experts as a kind of encyclopedia , “Encyclopedia of Russian Life” (Belinsky), “literary encyclopedia” (Fennel, after Johnston etc.). The main character of the poem, the narrator (not to be confused with the author himself) does not leave the stage for a single moment. He comments, interprets and parodies not only the action, but everything that is related to this action in the broadest sense, as well as everything that is or could be used to describe such an action. In particular, all known styles of literature, all literary topics, all literary arguments in progress and - last but not least - Pushkin's own development history in literature, including everything that he regards as his mistakes, are dealt with in precise form, although here too with irony and biting ridicule is not spared. Pushkin supports his narrator in this endeavor by underlining each statement with its own music, i. H. duplicated by the shape. The work is therefore regarded as absolutely unique because of this merging of form and content.

The aftermath

The verse novel is considered a masterpiece of Russian literature. With him, Pushkin ushered in the period of the great, realistic-poetic novel. For the first time in Russian literature, people appear here as they found themselves in the society of that time. The realism is reflected in the more than one hundred secondary characters and their specific location in their respective social environment. As Ulrich Busch explains in the foreword to his Onegin translation, the “contemporaneity of author, hero and reader” gives the verse novel a realistic character, which is new in the Russian literature of the time, and so the novel became an early example of the interpreted realistic 19th century Russian novel.

In the figure of Eugene Onegin, Pushkin created the type of superfluous man who was to find its successor in many varieties in 19th century Russian literature. Like the romantic hero of a Lord Byron , he stands on the fringes of society. Taking on responsibility of whatever kind does not occur to him or is denied from the outset in the social reality in which Pushkin writes his books - the omnipresent control by reactionary state organs in Tsarist Russia. A child of the upper class of society, financially independent, educated and well-read, a slacker, he looks at people, their feelings and their conventions with irony and sarcasm that can reach cynicism . Incapable of empathy , he plays with the feelings of those close to him. The basic motivation for his trade is his own pleasure, the basic mood of his life is boredom - the ennui .

In the form, in the brilliance and musicality of his verses, the perfect amalgamation of form and content, in which the poem, despite its highly artificial verse form, can be read as easily and fluently as prose, Pushkin's Onegin has remained a solitaire , albeit a solitaire Occasional attempts have been made to use the form created by Pushkin.

Vikram Seth created a verse novel in The Golden Gate from 1989, which consists of 590 Onegin punches. The book is about a group of young people, about a student and his girlfriend in California in the 80s with their typical problems: civil disobedience, gender debate, homosexuality, Christianity, nuclear war, etc. According to Seth's own statements, he was hit by the Comparison of two English Onegin translations inspired and found to his own surprise that he found here a form that was suitable for a narrative that had already been conceived. A second attempt is made by the Australian poet Les Murray . The theme of the story, which takes place between the two world wars, is the odyssey of a young Australian that takes him from Australia via the Holy Land to America in the 20s with its problems of prohibition and economic depression , to Germany in the 30s and in the Far East during World War II, and which ends with his return to Australia. The work is written in Onegin stanzas with extensive use of the rhyme scheme.

Origin and publication history

In 1817 Pushkin took up his first position as college secretary in the Foreign Office in St. Petersburg, in 1820 his poem Ruslan and Ludmilla was published, his first great literary success.

In the same year he was transferred to the south of the Russian Empire for his satirical epigrams and epistles directed against the tsar and the court , which were in circulation as unprinted manuscripts, where he led an unsteady life with numerous changes of location. In 1824 he finally resigned from court service and was exiled to a family estate in the Pskov governorate . In 1823 he had started work on Eugene Onegin , which he is now intensively continuing. The first chapter was published in 1825. In 1826 he was pardoned by the new Tsar Nicholas and was allowed to return to St. Petersburg, where he read from the Onegin publicly and immediately dealt with problems with the state censorship again. During the cholera epidemic of 1830 he returned to his estate, where he continued to work intensively on the novel. In 1831, the year of his marriage to sixteen-year-old Natalja Goncharova , after eight years he finished the novel that accompanied the most difficult time in his life.

The novel was published in St. Petersburg from 1825. The second chapter was printed in 1826, chapter 3 followed in 1826, chapters 4 and 5 in 1828, chapter 6 in 1829, chapter 7 in 1830 and the last chapter in 1832, all in St. Petersburg. The complete version was published in Moscow in 1833, and in 1837 the last edition, which Pushkin himself looked through.

Translations

German editions and translations

in prose or rhyme form

- Carl Friedrich von der Borg , Eugenius Onegin, First Section, in The Refractor. A Centralblatt Deutschen Lebens in Russland Dorpat, 1836 in five episodes, beginning August 1, 1836 in No. 14, ending in No. 18 of August 29, 1836

- Alexander Pushkin. Seals. Translated from Russian by Robert Lippert. 2 volumes Leipzig, Engelmann 1840.

- Contains the complete translation by Eugene Onegin.

- Friedrich Bodenstedt , publishing house of Decker's Secret Upper Court Book Printing Company, Berlin 1854

- Onegin. Novel in verse. Freely translated from the Russian by Adolf Seubert . Reclam, Leipzig 1874.

- Eugén Onégin . Novel in verse. Translated by Alexis Lupus. Leipzig, St. Petersburg Richer 1899.

- Theodor Commichau, G. Müller Verlag, Munich / Leipzig 1916.

- Verse translation in which the meter and rhyme scheme are retained. The translation by Commichau forms the basis for several subsequent revisions.

- Theodor Commichau and Arthur Luther , Bibliographisches Institut , Leipzig 1923

- Theodor Commichau and Arthur Luther and Maximilian Schick, SWA-Verlag, Leipzig / Berlin 1947.

- Theodor Commichau and Konrad Schmidt , Weimar 1958.

- Theodor Commichau and Martin Remané. Reclam, Leipzig 1965

- Eugene Onegin . From d. Soot. trans. by Theodor Commichau, Michael Pfeiffer u. Lieselotte Remané . In: Alexander Pushkin: Masterpieces. 4th edition. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1982. (Library of World Literature); Verse translation.

- Eugene Onegin . Translated into German by Elfriede Eckardt-Skalberg, Bühler Verlag, Baden-Baden 1947.

- Eugene Onegin . From d. Soot. trans. by Johannes von Guenther . Reclam, Leipzig 1949. (Alexander Puschkin. Selected works. Berlin, Aufbau Verl. 1949. pp. 9–213.)

- Eugene Onegin and other poems . Manfred von der Ropp and Felix Zielinski. Winkler, Munich 1972

- Eugene Onegin . A novel in verse. Trans. U. Nachw. Kay Borowsky . Reclam, Stuttgart 1972

- Prose translation

- Yevgeny Onegin . Novel in verse. From d. Soot. by Rolf-Dietrich Keil . Giessen: Schmitz 1980; Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 1999. Insel paperback. 2524. (Rhyming Verses)

- Eugene Onegin . Novel in verse. Transfer from d. Soot. u. Afterword by Ulrich Busch. Manesse, Zurich 1981

- Verse translation in which the four-footed iamb and the rhyme scheme are retained.

- Evgeny Onegin . Russian - German parallel edition in the prose translation by Maximilian Braun . Edited by Vasilij Blok u. Walter Kroll. Comments u. Selected bibliography. 2nd Edition. Goettingen 1996

- Eugene Onegin . A verse novel. From the Russ. by Sabine Baumann, with collabor. by Christiane Körner . Preface u. Introduction by Vladimir Nabokov . From d. Engl. By Sabine Baumann . Stroemfeld, Frankfurt am Main 2009

- A prose translation that retains the lines but does not take meter or rhyme into account.

Translations into English

There are just over 40 English verse or prose versions of the novel. The novel was first translated into English in 1881 by Henry Spalding. It was published under the title Eugene Onéguine: A romance of Russian life in 1881 by Macmillan in London. Spalding (1841-1907) was Lieutenant Colonel in the Royal Army, participant in the Boer Wars and was from 1880 in retirement.

In the 1930s there were translations by Oliver Elton (1861-1945), Professor of English Literature in Liverpool, by Dorothy Prall Radin (1889-1948) and George Z. Patrick (1886-1946), printed in Berkeley at the University of California Press , as well as in 1936 by Babette Deutsch , who retained the die form of the original. It was also published in the USA by the Heritage Press in New York and was reissued in 1943 in a version revised by German and with illustrations by Fritz Eichenberg .

In 1963 the translation in verse by Walter W. Arndt (1916–2011), which was awarded the Bollingen Prize, was published, which was followed in 1992 by a thoroughly revised new version. Arndt was a professor of Russian and German literature at Dartmouth College . In 1964 Vladimir Nabokov wrote in The New York Review of Books under the title On Translating Pushkin Pounding the Clavichord a flaming criticism of Arndt's translation, ... to defend both the helpless dead poet and the credulous college student from the kind of pitiless and irresponsible paraphrast whose product I am about to discuss.

In 1964 Nabokov's own translation of Eugene Onegin, on which he had been working since 1949, was published, the most time-consuming of his works. While teaching at Wellesley College , he had invited Edmund Wilson to work with him on a new Onegin translation, as he considered all previous ones to be inadequate. However, after a resinous beginnings, there was no long-term collaboration. While working on the text, Nabokov came to the conclusion that a translation of Eugene Onegin into English, in which rhythm and metrics should be retained, was impossible. So he started a word-for-word translation. In 1958 Nabokov had completed his prose translation, but had difficulty finding a publisher because of the size of the commentary, which had now swelled to two volumes. In 1964, the work was finally published by Princeton University Press . It comprises four volumes, apart from Nabokov's “literal translation”, a commentary in which he explains the content, the topics, the historical, cultural and literary context and presents Pushkin as a cosmopolitan who is influenced by the French language and literature . There are also two appendices, an index and a facsimile of the second edition of the Onegin text from 1837, the last one that Pushkin himself looked through. Wilson wrote him a slap that led to his final break with Nabokov. Although Nabokov vehemently defended his translation in public, he set about revising the text, which he declared finished in 1967: "I am now done with this diabolical task forever."

Although it remains controversial, none of the following translators can do without Nabokov's work with his Compendium of the Pushkin World. The recent German translation of Sabine Baumann refers to Nabokov, as well as the English translation of Charles Johnston (1977), which, like the version of Arndt retains the die, and in a revised version and with an introduction by the 2003 John Bayley new was brought out.

In 1990 James E. Falen's translation of Eugene Onegin was published, a revised version of which was reprinted in 1995 in Oxford University Press, and of which an audio edition, read by Stephen Fry , has since been produced. Falen's version, in which the meter and rhyme scheme are retained, together with the translations by Arndt and Johnston, is considered to be the closest in all respects to Pushkin's text.

An idiosyncratic version of Onegin comes from the physicist and cognitive scientist Douglas R. Hofstadter , who even tried to learn Russian out of enthusiasm for the book and Falen's translation. His onegin is an attempt to translate “Pushkin's brilliant poetry into the medium of contemporary English - or better, contemporary American”. Be maintained while translating should rhythm, rhyme, meaning and tone ( Rhythm, rhyme, sense, and tone ), an extreme opposite position to Nabokov - "the disgusting Non-Verse- [EO] of Nabokov" ( the vile non-verse of Nabokov ), as he calls it.

Translations into French

The first translation into French was made by Ivan Turgenev and Louis Viardot (1800–1883). The prose translation was published under the title Alexandre Puchkine, Eugène Onéguine in 1863 in the Revue nationale et étrangère . In 1868 a second prose translation by Paul Béesau appeared in the Librairie A. Franck in Paris.

A French translation, in which both the stanza form and the rhyme scheme have been retained, comes from the poet and translator André Markowicz (* 1960) and was published in Arles in 2005 by Actes Sud.

During his student days, the former French President Jacques Chirac wrote a translation that was never published.

Translations into Italian

The first translations of Eugene Onegin were written in 1906 by Giuseppe Cassone and in 1923 by Ettore Lo Gatto (1890-1983), who had his prose translation in 1950 followed by a verse translation in which the rhyme scheme is retained. Giovanni Giudici's verse translation appeared in 1976 and was re-edited in 1983 by Rizzoli in Milan. The Slavist and professor at the University of Trento, Pia Pera (1956-2016) created a translation into free verse.

Translation into Spanish

In 2005 Eugenio Oneguin appeared. Novela en verso . Versión en español directa del ruso en la forma poética del original, notas e ilustraciones de Alberto Nicolás Musso. at Zeta Editores, Mendoza 2005. In 2017, Editorial Meettok published a critical, bilingual edition with a translation by Manuel Ángel Chica Benaya.

reception

Funded by the opera version of the novel by Peter Tchaikovsky, the public perceived the novel to be shortened to a romantic love story full of renunciation, while the socio-critical aspect and the broad panorama of culture and society in Russia in the time of Tsars Alexander and Nicholas , which Pushkin in unfolded in his novel, has been largely disregarded.

Opera, ballet, drama, literature

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed to a libretto by Konstantin Shilovsky based on Pushkin's original, the opera Eugene Onegin with the subtitle Lyric scenes that on March 29, 1879 Moscow Maly Theater of students of the Moscow Conservatory under the direction of Nikolai Rubinstein premiered has been. Two years later the opera premiered at the Bolshoi Theater under the direction of Eduard Nápravník . The opera is one of the most frequently performed works on European and American stages.

August Bernhard, Max Kalbeck and Wolf Ebermann wrote German libretti for Tchaikovsky's opera Eugen Onegin , together with Manfred Koerth .

In 1959, the Russian director Roman Tikhomirov filmed the opera, the main roles were sung by stars of the Bolshoi Theater. In 1988 the opera was filmed again as a joint production of four European TV stations. Directed by Petr Weigl , the orchestra of the Royal Opera House performed under the direction of Georg Solti .

The theme was implemented by John Cranko as a ballet to music by Tchaikovsky, edited by Kurt-Heinz Stolze , and premiered in 1965 by the Stuttgart Ballet .

In 2009, Onegin with the choreography by Boris Eifman was premiered in Moscow by the Petersburg ballet . The music is a mixture of the most famous numbers from Tchaikovsky's opera and guitar solos by Alexander Sitkovetsky .

On the 100th anniversary of Pushkin's death, the Russian author Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsk wrote a stage version of the novel, for which Prokofiev composed the music. However, the play fell victim to Stalin's cultural policy and was never performed. The sheet music remained lost until 1960 when piano reductions appeared in Moscow archives. Prokofiev's composition op. 71 was premiered on April 4, 1980 on BBC Radio 3 under the direction of Edward Downes , who also took over the orchestration. In 2012 it was first performed as a play with incidental music at Princeton University.

Christopher Webber's (* 1953) drama Tatyana premiered in 1989 at the Nottingham Playhouse under the direction of Pip Broughton. In his piece, Webber combines spoken dialogues from Eugene Onegin with musical arrangements from Tchaikovsky's opera and depicts Tatyana's dream (Chapter 5, XI-XXIV) on stage.

In 2014 the ballet “Tatiana”, commissioned by the Hamburg State Opera, had its premiere at the Hamburg State Opera with music by Lera Auerbach , the libretto and choreography by John Neumeier based on Pushkin's novel. The Russian premiere of the piece, produced in cooperation between the two houses, took place on November 7, 2014 at Moscow's Stanislavsky Theater .

In 2015, the Vakhtangov State Theater in Moscow produced a staged performance of the novel, directed by the Lithuanian Rimas Tuminas , of which a feature film was produced in 2017.

In 2016, the French-British author Christine Beauvais retold the novel under the title “Songe à la douceur” as a love story between 14-year-old Tatjana and 17-year-old Onegin. In her romantic story, which is aimed at a young audience, she uses motifs from both Pushkin's novel and Tchaikovsky's opera. The book is in verse - but not written in Onegin verses - and is characterized by a playful type area from.

Movie

The material has been filmed several times since the first silent film in 1911, most recently Onegin (1999) with Ralph Fiennes in the title role.

There are also the two opera adaptations by Roman Tikhomirov and Petr Weigl.

Visual arts

In addition to Ilya Repin , the most famous scenes in the novel were painted by several Russian painters of the 19th and early 20th centuries. There are also various cycles that illustrate the entire novel, e.g. B. by Johann Matthias Ranftl , Josef Engelhart or Fritz Eichenberg .

literature

- Andreas Ebbinghaus: Evgenij Onegin . In: Kindlers Literature Lexicon. Edited by Heinz Ludwig Arnold. 3. completely rework. Ed. Vol. 13. Stuttgart: Metzler 2009. pp. 317-319.

- Vladimir Nabokov : Commentary on Eugene Onegin . From d. Engl. By Sabine Baumann. Frankfurt a. M .: Stroemfeld 2009. ISBN 978-3-86600-018-6

- Roland Marti: From “superfluous people” to the Onegin Code. ASPuskin's Evgeny Onegin. In: Ralf Bogner u. Manfred Leber (Ed.): Classic. New readings. Saarbrücken: Universaar 2013. pp. 99–114. ISBN 978-3-86223-098-3 full text, PDF

- Juri Lotman : Alexander Pushkin - life as a work of art . Translated from Russian by Beate Petras, with an afterword by Klaus Städtke . [1989]. Leipzig: Reclam 1993. (Reclam Library. 1317.) ISBN 3-37900487-1

Web links

- Pushkin's Eugene Onegin in full text (Russian)

- Pushkin's Eugene Onegin in full text (in the old Russian spelling used by Pushkin himself. Based on an edition from 1837, pdf)

- Excerpts from the novel Evgeny Onegin Russian / German (translation by Rolf-Dietrich Keil )

- German translation by Th. Commichau, full text on zeno.org

- Douglas Hofstadter: Essay: What's Gained in Translation In: The New York Times on the web. December 8, 1996.

Remarks

- ↑ = the Petersburg society

- ↑ Reinhard Lauer: Aleksandr Puskin. Munich: Beck 2006. p. 140.

- ↑ Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin. First published in 1964, Princeton University Press.

- ^ German Pushkin Society , accessed on October 15, 2015.

- ↑ quoted from: Karina Iwaschko: Pushkin as a surgeon of the Russian language . In: radio. Voice of Russia. December 12, 2014

- ↑ quoted in Alexander Pushkin: Eugen Onegin . A novel in verse, Reclam, UB 427, afterword

- ↑ (the medium as a message, 1823)

- ↑ John Fennell: Pushkin , Penguin, London 1964, introduction

- ↑ Alexander Pushkin: Eugene Onegin. Afterword by Ulrich Busch. Zurich: Manesse 1981. p. 222.

- ↑ Kelly L. Hamren: The Eternal Stranger. The Superfluous Man in Nineteenth Century Russion Literature. Download Liberty university, Masters Theses. Paper 180.

- ↑ John Fennell: Pushkin . London: Penguin 1964. Introduction

- ^ The Golden Gate. First edition New York: Random House 1986.

- ↑ Vikram Seth. Interview by Ameena Meer ( Memento from November 22, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Bombmagazine 33, fall 1990, accessed on November 21, 2015.

- ↑ Les Murray: Fredy Neptune , English / German, transl. Thomas Eichhorn, Ammann 2004

- ↑ Ruth Padel: Odysseus of the Outback. In Les Murray's saga in verse, an itinerant Everyman travels through the 20th century. The New York Times on the Web. [1] Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ↑ Alexis Lupus; only the 1st chapter

- ↑ Baumann on her translation , European Translators' College , Straelen , speech of thanks for the translator award of the Kunststiftung NRW

- ^ Henry Spalding 104th Foot; Anglo-Zulu War . Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ↑ ... to protect both the helpless dead poet and the gullible college students from such a merciless and irresponsible gossip (= paraphrase ), the product of which I will now discuss.

- ↑ Vladimir Nobokov: On Translating Pushkin Pounding the Clavichord . In: The New York Review of Books. April 30, 1964. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ Funke Buttler: On Translation . Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ Sara Funke Buttler. On Translation. Document: Nabokov's Notes . The Paris Review. February 29, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ↑ "I am now through with that diabolical task forever", quoted from Sara Funke Buttler: On Translation.

- ↑ German Versions of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin

- ↑ Hofstadter's translation of Book 1, 1-60. Full text

- ↑ "Pushkin's sparkling poetry in the medium of contemporary English - or rather, contemporary American to be transferred", Douglas R. Hofstadter: On "poetic lie-sense" and translating Pushkin; Analogy as the Core of Cognition , accessed September 25, 2015.

- ↑ Quoted from Eugene Onegin in English: Comparing Translations , accessed on May 9, 2019

- ↑ full text

- ↑ Jacques Chirac, décoré au Kremlin, célèbre la “démocratie” russe ( memento of January 10, 2017 in the Internet Archive ), AFP , June 12, 2008, accessed on September 4, 2019

- ↑ Eugenio Oneghin. Romanzo in versi. Edition 1967

- ^ Yevgeni Onegin (1959) | IMDb , accessed September 23, 2009.

- ^ Eugene Onegin (1988) | IMDb , accessed September 23, 2009.

- ^ Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg: Onegin

- ^ Eifman's 'Onegin' suffers from an identity crisis ( memento April 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on March 2, 2019.

- ↑ Clive Bennet: Prokofiev and Eugene Onegin. In: The Musical Times. Vol. 121. No. 1646.1980. Pp. 230-233.

- ↑ James R. Oestreich: Prokofiev Version of 'Eugene Onegin' in a Russian Weekend at Princeton. The New York Times. February 12, 2012.

- ↑ Ball at Larins, on youtube , accessed on September 23, 2015.

- ^ New Neumeier Ballet “Tatiana” by Lera Auerbach

- ↑ Petra Krause: Neumeier the esthete. Review of the world premiere, accessed on September 22, 2015.

- ↑ Eugene Onegin Filmstarts.de, accessed on May 5, 2019

- ↑ Songe à la douceur - Clémentine Beauvais book review, French, accessed on November 13, 2018