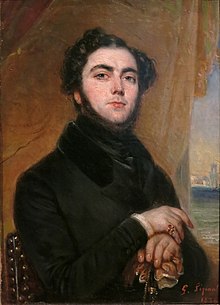

Eugène Sue

Eugène Sue , actually Joseph-Marie Sue (born December 10, 1804 in Paris , † August 3, 1857 in Annecy ) was a French writer . This author, little known today, was one of the most widely read and influential novelists in France in the 1840s . He went down in literary history as one of the founders of the serial novel in daily newspapers and as the author of what is perhaps the most successful feature novel of all, Les mystères de Paris ( The secrets of Paris ).

Life and work

Youth and becoming

Sue grew up the son of a wealthy and highly respected chief doctor and his second wife. He left high school prematurely at the age of 16 and initially apprenticed to his father as a doctor's assistant without any academic training. In 1823 he took part in the French army's Spanish campaign as an assistant surgeon and stayed for a while with the troops stationed in Cadiz . In 1825 he moved to the Navy in Toulon . It was here that he practiced his pen as a journalist for the first time . In 1826, as a young naval doctor, he made two long voyages ( South Seas and Antilles ) and in 1827 was there in the victory of the united Anglo-French-Russian fleet against the Turkish-Egyptian fleet off Navarino , which contributed decisively to the independence of Greece .

Back in Paris in 1828, Sue was interested in painting , but also worked as a journalist with articles for the magazine La Mode by Émile de Girardin , who in the following years revolutionized the French press with the introduction of the advertisement and the resulting cheaper newspapers . Sue wrote the first narrative texts for La Mode , e. B. Kernock le pirate and El Gitano (Spanish for "The Gypsy").

In 1830 he inherited an important fortune from his father and began a dandy life in the best Parisian circles. On the side he continued to write short stories and novels for various magazines. In the years from 1835 to 1837 he published a five-volume Histoire de la marine française . After he had almost used up his father's inheritance in 1838, he tried to earn a living by writing. At first he was mainly active in the currently fashionable genre of the "moral novel", but also tried his hand at a co-author as a playwright .

Act as a socially committed writer

In 1841 Sue changed from an apolitical dandy to a committed socialist who began to be interested in the problems of the Parisian proletariat, which was growing rapidly with industrialization , and tried to translate this interest into literature.

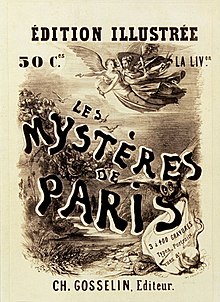

Sue became suddenly famous in 1843 with the Mystères de Paris (The Secrets of Paris), which appeared almost daily from June 19, 1842 to October 15, 1843 in the (rather conservative) daily Le Journal des Débats and became a literary and social one First-rate event. This work, which does not follow a single-minded plan and consists of a series of loosely arranged episodes, in which countless reader suggestions from all sections of the population have flowed, is about scheming aristocratic parties and especially the Parisian lower class milieu, whose difficult everyday life between work, misery and crime of Sue is portrayed partly realistic, partly picturesque, idealizing, but always exciting and with growing concern. A central person and figure of identification of the author is the Comte (dt. "Graf") de Gérolstein, who goes incognito among the people as "Rodolphe" and appears rescuing and avenging as a kind of " Superman ". A seven-hour theatrical version that Sue co-wrote with a co-author in 1844 was also a great success.

He then continued the novel form of the Mystères with Le Juif errant (The Eternal Jew), which came out from June 1844 to October 1845, now in the more left-wing paper Le Constitutionnel , and in which he increased his social and, above all, his political commitment, and in the sense of a radical anti-clericalism. Antoine-François Varner wrote the Vaudeville Le nouveau juif errant based on this model .

Another attempt by Sue in the Constitutionnel was less successful with the socially committed novel Martin l'enfant trouvé (Eng. "Martin the foundling") in the years 1846/47. The sequel Les sept péchés capitaux (Eng. "The Seven Deadly Sins") 1847–51 , which is again close to the moral novel, was also only moderately successful .

In the February Revolution of 1848 Sue appeared as a left-wing journalist and political activist, who was also elected member of parliament in 1850.

After the coup d'état by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte in 1851, he was briefly arrested and emigrated to the then (until 1860) still Piedmontese Savoy . Here, along with other fictional and political texts, he finished a work that had begun in 1849 and finally comprised around 6000 pages: Les Mystères du peuple (“The secrets of the people”). It is a history of France seen from below, so to speak, from the Celtic period around 50 BC. Until 1848, depicted as a family saga of a Breton lower-class family.

After completing this book in 1856, Sue went on a major European tour and died a few months after returning. Another monumental work, Les Mystères du monde (“The secrets of the world”), which was supposed to depict injustices and hardships around the world, did not get beyond beginnings.

The secrets of Paris

The plot of the story, which originally appeared as a serialized novel in the features section, can hardly be reproduced in brief because of its complexity. For illustration, the table of contents of chapters 1 to 14 is given below. The complete edition from 1988 comprises 169 chapters in 15 parts plus an epilogue on a total of 1977 illustrated pages. Most editions of the novel cover 65 chapters.

The story takes place in Paris in the middle of the 19th century: In a poor district, different people meet in the pub "Zum White Rabbit". The "stabber" (a crook), the "singer" (a 16-year-old orphan), also called "Marienblume", the "owl" who raised and abused her and the "schoolmaster", a robbery who escaped from prison and Ally of the owl. A stranger protects the singer from the knife. He speaks English with his own kind and calls himself "Rodolphe". His ally is a disguised "coal bearer" named Murph, who warns him that "Sarah" and "Tom" are on his trail. He flees from the two, who shortly afterwards ask for him in the bar and also speak English. When Sarah and Tom leave the pub, they are attacked and robbed by the schoolmaster. To save their lives, they promise to give him more money to be handed over at a meeting on a plane outside Paris. Meanwhile Rodolphe brings the singer to a wealthy farmer in the country, who was his wet nurse, in order to free her from the pressures of need. Back in Paris he wants to set a trap for the schoolmaster, who sees through him and almost kills him. Rodolphes assistant, the coal carrier, who is actually an English nobleman, is seriously injured. A black doctor, David, takes care of the two and addresses Rodolphe as "Highness". In the meantime the stabber has also become an ally of Rodolphes. To thank him, Rodolphe gave him an estate in Algeria that had to be defended against Arabs and thus also accommodated the combative impulses of the knife stabber. In the fight between Rodolphe and the schoolmaster, Rodolphe's men manage to capture the latter. Rodolphe does not want to hand him over to justice or kill him himself, but rather weaken him and give him the opportunity to repent. He lets David take his eyesight out of him and gives him a small pension that he is supposed to use in a nursing home in the country. The schoolmaster swears revenge on him. It also turns out that the peasant woman was the wife of the schoolmaster, who had been a successful businessman in his previous life. Because of his bad character, he gambled away his fortune and became a criminal. With the farmer's wife he has a son who he kidnapped and who then escaped, but who is mentioned in a document and still plays an important role in the course of the later plot. The reader now also learns that Rodolphe is a ruling German Grand Duke and that Sarah and Tom are former noble friends who became opponents due to an incident.

In the further course of chapters 15 to 65 it becomes clear that Rodolphe had a relationship with Sarah, an English duchess, from whom an illegitimate child emerged, namely the singer. In order to get rid of it, Sarah gave this child to the notary Ferrand, famous for his honesty, with the task of caring for it and providing it with a life pension that would benefit the carer in the event of death. Ferrand had the child sold to the owl for little money through a straw man and issued a fake death certificate for the girl. He shared his life pension with the “carer”. A young man, Germain, who worked at Ferrand, turns out to be the prodigal son of the schoolmaster and the farmer's wife. After many detours, the singer was legitimized as the child of Grand Duke Rudolf von Gerolstein, formerly Rodolpe, and became a princess. She falls in love with a duke, but cannot forget her past as a Parisian street girl and therefore goes to a convent. There she becomes abbess, but dies soon after. The schoolmaster kills the owl who uses his blindness to mistreat him and ends up in the madhouse. His last consolation is that his son forgives him. Interwoven into the plot are a number of other characters who either find happiness or fate's revenge.

The effect of the story is based not only on the surprising twists and turns and frequent moments of tension, but also on the atmospherically dense depiction of different milieus and the vivid depiction of different characters.

effect

Sue's serial novels of the 1840s and its countless translations and imitations across Europe marked the breakthrough of the new genre of the serialized novel in the feature pages of many newspapers newly formed, in turn, to a wide audience hoped that easily konsumierbarem reading higher buyer numbers and greater market share.

Of all foreign authors in the 19th century, Sue, alongside Charles Dickens, had the most profound influence on contemporary German literature, from high-level to the fields of trivial literature and colportage . This is particularly true of the “Secrets of Paris”, which immediately after its publication in Germany circulated in numerous parallel translations and caused a flood of imitators. Above all, authors of undemanding entertainment literature wanted to reveal the "secrets" of European capitals and German capital cities and for the first time looked at the criminal underworld and social defects of urban life. Sue rubbed off both on the social novel in the pre-March and post-March period ( Ernst Dronke , Hermann Klencke , Luise Mühlbach , Theodor Oelckers , Louise Otto-Peters , Robert Prutz , Georg Weerth , Ernst Willkomm ), as well as on authors of realism by Gutzkow and Raabe via Gustav Freytag to the old Fontane . Fontane still counted Sue's “Secrets of Paris” and “The Eternal Jew” among the “best books” in 1889. While the authors of Poetic Realism transfigured, faded out or whitewashed with humor (following Dickens), Sue was much more radical in his representation of reality after 1850 and can be considered a forerunner of the naturalistic movement . Sue not only gave wings to the German feuilleton novel, but also had an immense impact on the development of the Kolportag novel from John Retcliffe to Karl May .

Sue's contribution to raising awareness of the social problems of the time can also hardly be overestimated. A witness to this is Friedrich Engels , who wrote in February 1844: “The well-known novel by Eugène Sue, The 'Secrets of Paris', has made a deep impression on public opinion, especially in Germany; the haunting way in which this book depicts the misery and demoralization that is the lot of the 'lower classes' in big cities must necessarily have drawn public attention to the plight of the poor in general. ”Just a year later, Marx and Engels a review of Sue's work by the Young Hegelian Franz Szeliga (the i. Franz von Zychlinski ) as an opportunity to critically examine the novel in the “ Holy Family ”. "Systematically and with biting sarcasm, Sue's uncontrolled journalistic ideas and the inconsistencies of his social utopianism, borrowed from Fourier , which only serves the reader's need for sensation, are mercilessly torn to pieces and refuted."

Another effect is the inclusion of passages from Les Mystères du Peuple by Maurice Joly in his conversations in the underworld between Machiavelli and Montesquieu of 1864, which in turn form an essential basis for the anti-Semitic martial protocol Protocols of the Elders of Zion , which is still widespread today .

A five-part miniseries , based on the serial novel The Secrets of Paris , was broadcast on First German Television in 1982 .

Works (translations into German, selection)

- The salamander. A novel from sea life . German from L [udwig] von Alvensleben . Peeters, Leipzig 1832. ("La Salamandre")

- The art of pleasing. Novella ("L'Art de Plaire"). Wigand Verlag, Leipzig 1844 (translated by Ludwig von Alvensleben ).

- The secrets of Paris. Translated by A [ugust] Diezmann. Vol. 1-8. With Illustr. by Theodor Hosemann . Meyer & Hofmann, Berlin 1843. (Attached to Volume 8: Gerolstein. The End of the Secrets of Paris . German by Heinrich Börnstein .)

- The Eternal Jew. German by Ludwig Eichler . Illustrated by C. Richard. 10 vols. Weber, Leipzig 1844/1845. Volume 2, digitized Volume 6, digitized .

- The secrets of Paris. Complete edition. Translated from the French by Helmut Kossodo . With contemporary illustr. Vol. 1-3. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 1988. (Insel Taschenbuch 1080); that. in two volumes. 2008, ISBN 978-3-458-35088-0 . - Full paperback edition. Translated from the French by NO Scarpi. Droemersche Verlagsanstalt Th. Knaur Nachf., Munich / Zurich, ISBN 3-426-02008-4

Imitations of the "Secrets of Paris" (selection)

- [Anon .:] The secrets of Berlin. From the papers of a Berlin criminal investigation officer. With illustrations in steel engraving by P. Habelmann. 6 vols., Berlin, 1844. (In 1987 an abridged and edited new edition by Paul Thiel was published by Das Neue Berlin.)

- August Braß : The Mysteries of Berlin . 5 vols., Berlin, 1844.

- L. Schubar [d. i. Rudolf Lubarsch]: Mysteries of Berlin . 12 vols. Berlin, 1844/46

- RB [d. i. Robert Bürkner]: Secrets of Königsberg. A novel. Vol. 1 [not published more]. Koenigsberg, 1844

- Julian Chownitz [d. i. Joseph Chowanetz]: The secrets of Vienna. 2 vols., Leipzig, 1844.

- Johann Wilhelm Christern : The secrets of Hamburg. 2 vol., Hamburg a. Leipzig, 1845.

- L. van Eikenhorst [d. i. Jan David de Vries]: Amsterdam's secrets. From the Dutch by E (dmund) Zoller. 12 parts, Stuttgart, 1845. (The foreign fiction. Vol. 395–406.)

- George Ezekiel : The Bastard Brothers or Secrets of Altenburg. Novel. From the estate of a detective. 2 vols., Altenburg, 1845.

- Suan de Varennes: The Mysteries of Brussels. German edited by E [dmund] Zoller. 13 Bdchn., Stuttgart, 1846/47. (The foreign fiction. Vol. 541–545, 801–808.)

- Heinrich Ritter von Levitschnigg : The secrets of plague. 4 vol., Vienna, 1853.

- Jakob Alešovec : Ljubljana Mysteries: Moral novel from the present . Ljubljana, 1868.

Adaptations of works by Sue

- The Mährlein von Fletsch und Winzelchen: A pretty and instructive story for children. After Eugène Sue, edited by Franz Lauter. - Frankfurt a. M: Ullmann, 1844. Digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Les Mystères de Paris was the model for Johann Nestroy's Posse Lady und Schneider from 1849 with music by Michael Hebenstreit

- L'Orgueil. La Duchesse was the model for Johann Nestroy's Posse Kampl from 1852 with music by Carl Binder

- Atar Gull or: The fate of an exemplary slave. Comic by Nury / Brüno based on the novel Atar Gull , Avant-Verlag, Berlin 2012

literature

- Peter Heidenreich: Text strategies of the French social novel in the 19th century using the example of Eugene Sue's “Les mystères de Paris” and Victor Hugo's “Les miserables”. Tuduv, Munich 1987. Series Language and Literature Studies Vol. 22. - Since 2004: Herbert Utz Verlag ISBN 3-88073-219-1

- Walburga Hülk : When the heroes became victims. Basics and function of social order models in the feature novels "Les mystères de Paris" and "Le juif errant" by Eugène Sue. Winter, Heidelberg 1985. Series: Studia Romanica Bd. 61. ISBN 3-533-03686-3 .

- Kurt Lange: Eugen Sue's sea novels. Your origin and character. Adler, Greifswald 1915.

- Materials for the criticism of the feature section novel. "The Secrets of Paris" by Eugène Sue. Edited by Helga Grubitzsch. Athenaion, Wiesbaden 1977. Series Literaturwissenschaft Vol. 3. ISBN 3-7997-0675-5 .

- Achim Ricken: Panorama and panorama novel. Parallels between panorama painting and literature in the 19th century, shown in Eugène Sue's “Secrets of Paris” and Karl Gutzkow's “Knights of the Spirit”. Peter Lang, Frankfurt 1991. Series: Europäische Hochschulschriften, R. 1: Deutsche Sprache und Literatur; Vol. 1253. ISBN 3-631-43725-0 .

- Bodo Rollka: The trip to the basement. Notes on the strategy of educational success. Eugène Sue's “Secrets of Paris” and Günter Wallraff's “Right Down”. Arsenal, Berlin 1987. Series: Berlin contributions to the pleasure of wit and understanding; 7. ISBN 3-921810-92-2 .

- Cornelia Strieder: Melodrama and social criticism in works by Eugène Sue. Palm & Enke, Erlangen 1986 (= Erlanger Studies; 66) ISBN 3-7896-0166-7

- Margrethe Tanguy Baum: The historical novel in France during the July monarchy. An investigation based on the works of the authors Frédéric Soulié and Eugène Sue. Peter Lang, Frankfurt 1981. (= Bonn Romance Works; 9) ISBN 3-8204-6175-2 .

- Andrea Jäger: Marx reads wars ... his opponents read Eugène Sue . In: Cultural philosophers as readers. Portraits of literary readings. Festschrift for Wolfgang Emmerich for his 65th birthday . Edited by Heinz-Peter Preußer and Matthias Wilde. Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2006 ISBN 3-8353-0011-3 , pp. 21-29

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans Felten: French literature under the July Monarchy (1830-1848). Haag et al. Herchen, Frankfurt am Main 1979, ISBN 3-88129-214-4 , p. 132.

- ↑ See: Erich Edler: Eugène Sue and the German mystery literature. Berlin-Neukölln: Rother 1932. (Dissertation, partial print.)

- ↑ See the basic work of Erich Edler: The beginnings of the social novel and the social novella in Germany. Frankfurt / M .: Klostermann 1977.

- ^ Theodor Fontane: Complete Works. Vol. 22/1. Literary essays and studies. First part. Munich: Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung 1963, p. 499.

- ^ Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Works. Vol. 1. Berlin: Dietz Verl. 1974, p. 497.

- ↑ See Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Works. Vol. 2. Berlin: Dietz Verl. 1974, pp. 172-221. (Chapter VIII: The course of the world and the transfiguration of "critical criticism" or "critical criticism" as Rudolph, Prince of Geroldstein .)

- ↑ Erich Edler: The beginnings of the social novel and the social novella in Germany. Frankfurt / M., Klostermann, 1977, p. 96.

- ↑ The Gemeimnisse of Paris , fernsehserien.de

- ↑ http://www.avant-verlag.de/comic/atar_gull_oder_die_geschichte_eines_modellsklaven/

Web links

- Literature by and about Eugène Sue in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Eugène Sue in the German Digital Library

- Works by Eugène Sue in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Eugène Sue on the Internet Archive

- Literature by and about Eugène Sue in the Berlin State Library

- About Eugène Sue with bibliographies

- Article in "Names, Titles and Dates of French Literature" (source for the "Life and Creation" section)

- Eugène Sue (1804-1857) - December 10, 2004, 200th birthday

- Works by Eugène Sue in the original French and in English at Project Gutenberg

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sue, Eugène |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Sue, Joseph-Marie (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 10, 1804 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 3, 1857 |

| Place of death | Annecy |