Eccentric: About the pleasure of being different

Eccentrics: On the Pleasure of Being Different (originally Eccentrics: A Study of Sanity and Strangeness ) is a popular science book published by clinical neuropsychologist David Joseph Weeks with journalist Jamie James in 1995; In 1997 it appeared in German.

The book is based on the results of a study by DJ Weeks and Kate Ward from the 1980s, published in 1989 under the title Eccentrics: The Scientific Investigation and which is the only scientific study on the subject to date.

For further explanations and explanations of eccentricity, the behavior of historically documented eccentric personalities is used in the book.

content

introduction

With the subtitle A paradise of the Nerds (in the original A Golden Age of Wierdness ) Weeks introduces the topic of eccentricity by the acceptance of historical eccentrics like I. Norton , oofty goofty , Uncle Freddie Coombs , King of Pain and the Great Unknowns who enriched the life of the public in San Francisco with their eccentric way of life in the mid to late 19th century .

Weeks notes that there wasn't a major study of eccentric people until the 1980s. Psychology hardly or vaguely defines eccentric behavior - eccentricity does not represent a clinical picture - and also a lexical definition such as "a person who deviates from the conventional or existing norm that is different from the others" is too general and could also refer to one, for example extreme criminals or a person with a rare disease.

Weeks began his research at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital in 1984 with the intention of sharpening the profile of eccentric people and of distinguishing between unusual, creative thinking and pathological behavior (the line between genius and insanity) . When mentioned in the media, the study reached a volume of more than 1000 eccentric subjects , mostly from the USA and England.

The premises of the study were

- Eccentricity is “nothing normal” and therefore rare.

- The spectrum of human behavior ranges from absolute social conformity to completely bizarre non-conformity. Eccentric people are to be expected with multiple and consistent behaviors in the area of nonconformity.

- Cultural factors play an important role as different societies also have different standards of conformity.

- The literature available up until the 1980s does not give a clear definition of eccentricity. The exclusion What is not an eccentricity? should therefore also be taken into account.

- Is there a connection to psychological illnesses - or rather not? Neurotics are often dysphoric and feel miserable, schizophrenics cannot control their visions or heard voices and develop feelings of fear, people with schizoid personality disorder avoid contact and are extremely introverted: Illness implies suffering. Eccentrics, on the other hand, give the impression of feeling childlike joy in living out their fantasies and living them out fearlessly in private or in public.

The topic in 12 chapters

Each chapter is preceded by a topic-related quote; occasionally there are two quotations.

In the individual chapters, Weeks quotes from the interviews of the study in order to explain the eccentric aspects that he has worked out with concrete statements. Example:

"I don't see the point in having a special room set aside to fall unconscious in."

"I don't see why I should reserve an extra room just to pass out in it."

The investigation

Weeks begins with the description of conceptual difficulties before the start of the study: Eccentrics are not geographically limited, have no other, clearly visible "group membership", ie the selection criteria that should only become apparent through the study were missing. These difficulties had to be solved creatively in order to find suitable test subjects for the planned study.

The first attempt to search were small notices distributed all over Edinburgh with the text: “Eccentric? If you feel that you might be, please contact Dr. David Weeks at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital ”and a telephone number. A journalist became aware of this and wrote an article about it in The Scotsman . This was followed by radio and TV interviews (also in all four BBC programs ) and distribution in the US media: New York Times , Wall Street Journal , Los Angeles Times , International Herald Tribune, etc. In total, the potential contacts rose to 140 million People appreciated. In retrospect, Weeks referred to this approach as “multimedia sampling”.

Among the reports received, there were around 10% "lonely people who wanted to talk to someone" in addition to the apparent pranksters . You came into contact with shy, introverted eccentrics indirectly, through friends or relatives. Extroverted eccentrics were ready to point out other befriended eccentrics.

After sorting out apparently non-eccentrics, the number of test subjects was around a thousand people from all classes (but mainly middle class) and professions, between 16 and 92 years (average 45 years) with a slightly above-average overall education, which had lasted on average 14 years. Statistically, one eccentric came to around 10,000 people (± 50%, ie 1: 5,000 to 1: 15,000).

The taped interviews were conducted as a field study in the personal environment of the eccentrics. In addition, standardized personality questionnaires , intelligence tests and tests for diagnosing schizophrenia and other mental illnesses were used.

The result was “a group picture of people who were as different as society as a whole”, but who, as a group, showed the following characteristics, found in decreasing frequency, the first five being found in almost every eccentric:

- unadjusted ;

- creative ;

- strongly motivated by curiosity ;

- idealistic and unshakably optimistic : with the aim of improving the world and making the people in it happier;

- happily runs one or more hobby horses ;

- is aware of being different from an early age;

- intelligent ( intelligence quotient around 115 to 120 on average);

- stubborn and outspoken ; convinced that you are right yourself and that the rest of the world is out of step;

- without competition , without a demand for recognition or confirmation by society;

- unusual eating habits and lifestyle;

- not particularly interested in the views or company of others, except for the purpose of convincing them of their own - right - point of view

- endowed with a mischievous sense of humor ;

- single ;

- usually the oldest or only child;

- incorrect spelling .

It concludes with detailed descriptions of several eccentrics in the study, which exemplify the first five properties.

Eccentric from four centuries

In the historical description of eccentrics, the exact facts must be taken into account, which are often less precise the further one goes back in time. This also includes the exact knowledge of the environment, the "normal behavior" regulated by law or code of conduct, because the eccentric behaves differently from the normal people living around him. As a historical person whose conclusion is eccentric or not? cannot be hit is called Nero . Edith Sitwell made exactly this mistake in her book The English Eccentrics , published in 1933 , by also describing charlatans and "decorated hermits" who behaved unusually for money.

The 150 historical eccentrics quoted by Weeks and James can be found in the period from 1551 to 1950 and are covered multiple times and through different, independent sources. As the oldest eccentric on this list, the Honorable Henry Hastings (1551-1640) is mentioned, an English landed gentleman and "original in the time in which he lived". Others are John Bigg (1629–1696), the "Dinton Hermit" (hermit from Dinton / Buckinghamshire) and Sir Thomas Urquhart (1611–1660), who allegedly died of a laughing fit . From around 1725 eccentrics were increasingly found.

An analysis of the historical eccentrics of Great Britain in relation to their social class gave the following result:

- High nobility 16%, land nobility 21%, upper middle class 49%, lower middle class 10%, working class 4%.

The explanation is that the rich and powerful ("idle classes") on the one hand had better conditions to let their eccentricity run free, on the other hand they are also interested in the interests of their fellow citizens who watch them carefully - and leave written evidence. Among the upper classes, for example, the writer and builder include William Thomas Beckford (1760-1844) and the politicians and especially morbid inclined towards George Augustus Selwyn (1719-1791). One of the rarer lower class eccentrics was the Scot Henry Prentice .

The tendency of the British class distribution also fits that eccentrics were hardly to be found in America during the tough pioneering days and that they only appeared from the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century. John Chapman (1774–1847) was known as "Johnny Appleseed" and dedicated his entire life to planting apple trees. Davy Crockett (1786–1836) also showed eccentric features. Many more examples follow, with the remark that the extroverts (about 3/4 of the 150 cases) were described as “popular and popular”, the introverts (about 1/4 of the 150 cases, including “recluses”) were more likely to be “ suspiciously "dealt with.

Historically eccentric women used to be documented almost exclusively in the upper classes. Among them was Victoria Claflin Woodhull (1838-1927), an American journalist, newspaper publisher, financial broker, spiritualist and one of the most famous women's rights activists of the 19th century. Other was the British writer and ambassador wife Margaret-Ann Tyrrell (1924-1939), who wrote a reinterpretation of world history hidden high in a tree in the embassy garden in Paris and Susanna Montgomery, Countess of Eglinton (1690-1780), who had dinner together ingested with trained rats whom she thought were more grateful than humans.

From the analysis of the 150 historical eccentrics (and as a demarcation from charlatans ) it is concluded: “Real eccentrics never act. They are strong individuals with their own peculiar tendencies [..]. They are not ready to compromise. "

Eccentricity and Creativity: The Artists

In 1952, Brewster Ghiselin published The Creative Process , the summary of a symposium on creative artists and scientists. He identified four phases of the creativity process:

- (1) Preparation : The creative person identifies “a problem” (issue) that should be solved, and acquires the knowledge and tools to tackle that problem.

- (2) Incubation : The topic sinks into the subconscious and the creative brain establishes (new) thematic connections.

- (3) Enlightenment : The creative solution "suddenly penetrates consciousness" and is implemented.

- (4) Verification : The new solution is subjected to an endurance test. Scientists carry out further empirical work, artists present their work to the public.

One of Weeks' test subjects suggested that “every move away from the applicable norm” is in itself a creative act and, in connection with pronounced individualism, fits into the “continuum” of eccentric behavior. The historical figures Jesus , Pablo Picasso and Igor Stravinsky are cited as examples . Quoting Sigmund Freud , there would be a “preservation of childlike openness to follow unconscious impulses”.

As part of Ghiselin's structuring, Weeks found the following results in his study:

- Three quarters of eccentrics describe themselves as creative (or are referred to as creative by others).

- There are two main groups of scientists and artists; a third, smaller group are the religious eccentrics.

- (1) Preparation and (2) Incubation: Eccentrics show “the phenomenon of total immersion” (an “increased emotional state”) by dealing with the topic spatially (drastically redesigning their surroundings) or physically (lifestyle, clothing, drugs) want to approximate direct visualization. The result can be a "vision".

- (4) Review: Here eccentrics differ from non-eccentrics in that they rarely doubt, they simply know, for example through their “vision”, that their approach is the right one - and follow it consistently.

- Explanations from eccentrics in the study support the evidence of a psychological study that found a direct correlation between the ability to visualize mental images and the ability to think creatively.

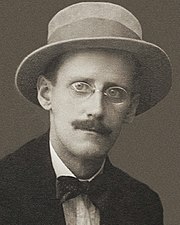

In addition to eccentric artists "whose annals would fill volumes" who have created significant things in their field, such as the poet Emily Dickinson (1830–1886), the writer James Joyce (1882–1941) and the artist Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) , there were also creative but “unusually bad” eccentrics who stuck to their vision of art all their lives.

The latter group includes Robert Coates (1772–1848), “the worst actor in the world”, who became famous primarily for his interpretations of Romeo , William McGonagall (1825–1902), “the worst poet of all time”, creator of “ Verses devoid of any euphony that violated the simplest laws of metrics, ”and the wealthy Florence Foster Jenkins (1868–1944), who gave singing concerts in a shaky and colorless voice without any talent and was able to spend one evening with Enrico Singing Caruso in the Metropolitan Opera . Her memorial inscription, which she wrote herself, reads: "Some people say I cannot sing, but none can say I didn't sing."

The scientists

From conversations with eccentric people who work as scientists, Weeks derived the following statements:

- Eccentric Scientists

- are “strongly theory-oriented” and are less based on their own experimental data.

- tend to advocate results with enthusiasm, having found "what should be right". Your “phase of critical analysis” is drowned in “a drunken frenzy of discovery”, while non-eccentric people repeatedly question, check and verify their own postulates and theories themselves.

- are less likely to be discouraged by inconsistencies in their theories.

- are more loners than team workers.

- make connections "which established science would declare beyond the limits of what is permitted" and follow unexpectedly consistent data with fascination.

Historical eccentric scientists are cited who were either laughed at in their time, but afterwards their theories turned out to be (partially) correct, or who were famous and respected in their time - especially due to the behavior of the eccentric - whose theories were mutually exclusive but later turned out to be mostly wrong.

An example of the first case is James Burnett, Lord Monboddo (1714–1799), a Scottish lawyer , man of letters, and amateur naturalist who, in The Origin of Language, was the first - and 70 years before Darwin - to propound the idea that the human tailbone was a What was left of its ape-like ancestors. Burnett was then exposed to "tail jerking" throughout his life, for example he was referred to as a "connoisseur of materia a posteriori ".

The animal magnetism of Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815) was famous in the 18th century and Mesmer celebrated it in theatrical performances, but in modern times it has only survived in esotericism . Mesmer's use of hypnosis, on the other hand, has been further explored in medicine.

Sunken continents and golden ages

This chapter deals with the religious and cultural visions of eccentrics and their effects on posterity.

The historical figures Jesus, Buddha, Mohammed and also Joseph Smith (1805–1844; founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints ) and Elspeth Buchan (1738–1791; founder of the Buchanites ) are viewed from this perspective. Due to the eccentric way of life and breaking with social norms, the messages of these people are "galvanized with their personal charisma".

Just like religious visions, according to Weeks, visions of civilizations that give culture, for example the myth of Atlantis, have occupied many eccentrics and made them come up with the most daring theses according to the principle "Nothing can prove that I am wrong".

These include Ignatius Donnelly (1831-1901) with his bestselling Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (1882; the book was published in more than 50 editions), or Augustus Le Plongeon (1825 to 1908), who published that Atlantis a branch of the Maya have been and Jesus spoke his last words on the cross in the Mayan language. James Churchward (1851–1936), who claims to have been gifted with mystical abilities, went one step further and, from 1926, described the even more important, also submerged continent of Mu - and thus continues to inspire writers and draftsmen today. Churchward had adopted the ideas of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891; co-founder of the Theosophical Society ), whose very complex history of civilization - which of course also includes Atlantis - was based on her own supernatural revelations, some of which can also be found in the Hindu Rigveda . At the time of her death, Blavatsky had more than 100,000 followers.

Weeks distinguishes these consistent and self-convinced eccentrics - “The real eccentric does not pretend” - from charlatans like Edgar Cayce , who offered their Atlantis services - contact and advice from the wandering souls of the Atlantids - for money.

Eccentricity and mental illness

An important element of the study was to compare the forms of perception of eccentrics with those of people with mental illnesses and, if possible, to delineate them. By default, Weeks is referring to an investigation at a UK university hospital that found only two eccentrics among 23,350 discharged patients after treatment for mental illness.

In Weeks' study, all subjects were subjected to the standardized present state examination interview (PSE interview), a questionnaire that has been used internationally since the 1960s in order to be able to easily standardize and classify the psychiatric status of patients, with three levels of each symptom ( strong / weak / absent). The presence and absence of symptoms are summarized in the table below.

| PSE symptom | Strongly present in eccentrics (in%) |

Weakly present in eccentrics (in%) |

Not available for eccentrics (in%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual hallucinations | 9 | 26th | 65 |

| Acoustic hallucinations | 5 | 25th | 70 |

| Delusional misinterpretation | 5 | 26th | 69 |

| Religious delusions | 4th | 41 | 55 |

| Paranormal delusions | 3 | 27 | 70 |

| Paranoia | 2 | 41 | 57 |

| Thought Transfer "Other people hear my thoughts." |

1 | 5 | 94 |

| Breaking off thoughts "My thoughts suddenly break off." |

1 | 29 | 70 |

| Delusion of foreign control of the mind |

1 | 11 | 88 |

| Influencing thoughts "Thoughts of others influence me from the outside." |

0 | 0 | 100 |

| Delusion mind reading |

0 | 38 | 62 |

According to Weeks, this results in the following statements:

- In comparison with the extremely wide range of psychological symptoms in normal persons (mild symptoms around 15%), eccentrics show the same symptoms less often (mild symptoms around 8%).

- 36% of eccentrics stated that they have other eccentrics (grandparents, uncles, aunties, distant relatives) in the family (unconfirmed hypothesis of a milieu theory ).

- The incidence of mentally ill relatives in eccentrics was slightly higher than that in normal people.

- Because of their ego-reference, eccentrics show practically no symptoms of "outside influence".

- There is no similarity between eccentrics and schizophrenics.

- Only one male out of more than 1,000 subjects in the study was diagnosed with psychosis.

Eccentric childhood

During the study, eccentric adults were asked about memories related to their childhood experiences. This resulted in

- that at least two-thirds believed they knew by the age of eight that they were different from everyone else.

- that a similarly large number believed that they could attach this knowledge to a very concrete experience in their youth.

- that many had experienced "phases of isolation" in childhood when they were excluded from families or peers because of their differences.

- that some believed they had deliberately evoked their parents' anger or disappointment.

- that from a “sensitivity to banality and boredom” they had “feelings of superiority” towards classmates at an early age.

- that they occasionally experienced affection from their peers as a "popular troublemaker and charismatic ringleader".

- that they had fewer problems during puberty than their peers due to their self-confidence gained at an early age.

The eccentric personality

Self-portrayal , a term from social psychology , is the staging strategy used in social groups in order to achieve a certain reputation with other people. It is methodically divided into five different tactics: being a role model, making yourself popular, promoting yourself, appearing in need of help and intimidating. Since eccentric people are more or less indifferent to the reputation of others - or their acceptance by others - Weeks suggests five new criteria for recording eccentric people.

- (1) rarity

- Unusuality (exceptionality) is rare. According to Weeks, the incidence of “classic eccentrics” is around 1: 10,000.

- (2) Being extreme

- With the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16 PF) by personality psychologist Raymond Bernard Cattell , 16 so-called personality factors can be examined. The results are given on a 10-point scale (1: absence, 10: saturation), and only 2.3% of an average population show the two extremes 1 and 10 at either end of the scale.

Weeks examined eccentrics with the 16-PF interview and put together what percentage of them find themselves at the upper or lower extreme value.

| 16-PF characterization | Eccentric in the extreme value range (in%) | Eccentrics in the extreme range (in%) |

|---|---|---|

| intelligent | 15th | 15th |

| dominant, assertive | 14th | 39 |

| straight ahead, spontaneously | 15th | 14th |

| suspicious | 11 | 10 |

| imaginative, unconventional | 11 | 8th |

| independent, resourceful | 10 | 7th |

| brave, bold | 7th | 11 |

| shy, shy | 7th | 1 |

| emotional | 7th | 3 |

| impulsive | 6th | 2 |

| sensitive, sensitive | 6th | 3 |

| selfish, disregarding rules | 6th | 6th |

| emotionally stable | 5 | 4th |

| reserved, distant | 5 | 5 |

| radical | 5 | 5 |

| tough, tough | 4th | 5 |

| seriously | 3 | 5 |

| confident, serene | 3 | 10 |

| following one's own instincts | 1 | 8th |

- (3) Special properties

- Weeks reports that the identification of eccentric people with a thing, a topic or an associated personality can be pursued to the point of "obsession". Eccentrics are fully aware of their own personality, but live out their topic with all the consequences.

- Another special feature is the eccentric humor. Weeks explains it using examples, ranging from subtle-absurd puns to unpredictable, brutal derailments.

- (4) Unusual combinations of behaviors and traits

- The way in which behaviors and properties can be combined in eccentrics is explained using the examples of Gerald Thywhitt-Wilson (bbb) and - from the study - John Slater. Slater, who had worked in more than ten very different professions, wandered barefoot, wearing only striped pajamas, Great Britain from Land's End in the south to John o 'Groats in the north, accompanied by his Labrador Guinnes, who made two pairs of women's thongs Wore suede. The librarian Thomas Birch, who lived in the 18th century and whose only goal was to fool fish disguised as a tree and to be a perfect angler, serves as a counter-example.

- (5) Doing ordinary things in an unusual way

- The estate owner John Alington (1795–1863) taught his farm workers geography on a walk-in (and navigable), true-to-scale model of the world. Pastor Francis Waring (1760–1833) gave short sermons of a few minutes on Sundays in up to three churches (which he reached by horse), let his children eat from a trough and slept with his wife in a wicker basket hanging from the ceiling.

- Eccentrics often seek and find ways of doing ordinary things in new, unusual ways. The following are examples from the study in which the subjects redesign their surroundings, often “protesting against the achievements of modern life”; H. they vehemently reject.

Weeks found all five criteria in around a quarter of all test subjects, many show three, and the vast majority show two of these criteria - in their “experiments in matters of subjectivity”.

The psycholinguistic analysis

This chapter reports the results of the psycholinguistic application of the TLC (communication disorders in schizophrenics) scale by psychologist Nancy Andreasen to interviews with eccentrics and non-eccentrics.

| TLC focus | Eccentric (in%) | Normal people (in%) |

|---|---|---|

| Urge to speak (or increased speed of speaking) |

35 | 6th |

| Strip a topic (answering a question in an indirect or off-topic way) |

33 | 2 |

| Awkwardness (unnecessarily detailed language or excessively verbose) |

32 | 6th |

| Referring to oneself (bringing the topic to itself again and again) |

28 | 1 |

| Language poverty (saying little or nothing on the subject) |

10 | 5 |

| Aimlessness (unable to follow a thought to the end) |

6th | 18th |

| Agreement on topic (jump from train of thought to train of thought) |

4th | 32 |

| Perseveration (repeating words or ideas over and over) |

2 | 8th |

The following conclusions, partially supported by literature from external research, are derived from these results:

- About two thirds (64%) of the eccentrics and about half (48%) of the eccentrics - compared to normal people - show no communication peculiarities at all.

- Speech patterns that are more common in normal people than eccentric people cannot be called “speech disorders”.

- Some eccentrics lack the tendency to digress.

- Referring to oneself is actually not surprising in an interview in which a person is asked about themselves. The increased "egocentrism" (compared to normal people) could be "an expression of their innocent, almost childlike conception of themselves and their worlds".

- With eccentrics (but not with eccentrics) there is a direct, significant connection between self-reference and creativity.

- Eccentrics are less likely to get off topic than normal people; they are thematically "more persistent".

- In summary: The results are referred to as "communication peculiarities" and not as "communication disorders" with the conclusion: "Even if eccentrics are sometimes annoying, absurd and puzzling, they are certainly never boring."

Eccentric women

The historical analysis shows that until around 1950, most of all documented eccentric people (85%) are men. The reason for this lies in the image of women at that time: women were more in the house and were less or less noticed in public. An eccentric man was more likely to be accepted in public because he was also the provider of the household. In the case of eccentric daughters or wives dependent on home owners, it was easy to find “ hysterical ” accommodation in a private institution.

Among the historically documented eccentrics, a quarter - from the point of view of their male descriptors - attracted attention because of their striking beauty and wealth. Wealth in particular meant independence, possibly power, and freedom for eccentric behavior.

From today's perspective, eccentricity differs significantly in women and men; it shows gender dimorphism . The following statements could be made after the study:

- Eccentric women tend to manifest themselves later in life; eccentric men manifest themselves earlier, from adolescence.

- Eccentric women tend to be more curious, more radical, more eager to experiment and more closed than men.

- Eccentric women tend to be aggressive. With regard to increasing aggressiveness, the following can be determined on average:

- Normal people <eccentric men <eccentric women; 40% of eccentrics appear in the top end of the scale.

- Two explanations are given for this:

- On the one hand, eccentric women still have to "defy society with courage" and counter social pressure.

- On the other hand, the perception of this increased aggression can result from a certain image of women, i. H. the same behavior that is perceived as "normal aggression" in a man gives the appearance of "increased aggression" in a woman.

The chapter closes with short biographies of well-known eccentric women such as James Berry , Lillie Hitchcock Coit , Mary Kingsley , Mary Edwards Walker and Viktoria Claflin Woodhall .

Sexual eccentricity

Defining “sexual eccentricity” is difficult because the perception and acceptance of certain sexual practices has changed over time. What used to be classified as symptoms of mental illness, personality disorders or perversion is now more or less dismissed as harmless deviations and otherness. Furthermore, the classification as eccentric is difficult or doubtful when it comes to groups of people who live in connection with one another in a form of sexual subculture .

The following tendencies were derived from the interviews with the eccentric people in the study:

- Eccentrics tend to be solitary and find it difficult to be physically intimate with other people.

- Eccentrics are generally "not particularly interested in sex".

- There is no evidence that the sexual practices of eccentrics differ from those of other people in any particular way.

- When eccentrics have a love affair, they go about it with their usual enthusiasm. After that, however, they have difficulty maintaining this relationship.

More than four fifths of the chapter deal with historical eccentrics who, in their time, through their libidinal behavior such as homosexuality ( Stephen Tennant , Siegfried Sassoon , Ronald Firbank , the Ladies of Llangollen (Eleanor Charlotte Butler and Sarah Ponsonby)), transvestism (the Abbé de Choisy , Ed Wood Junior ), sadomasochism ( TE Lawrence , Percy Graininger ), or combinations thereof ( Francis Dashwood , George Selwyn , John Wilkes ) caused a stir.

Eccentricity and health

The shortest chapter of the book presents results from the analysis of historical eccentrics and the interviews during the study.

- Eccentrics in the historical sample (1551 to 1950) have an average life expectancy of around 60 years, which, according to Weeks, is above the average at the time.

- The study eccentrics consulted a doctor about every eight years; when they did, it was almost always used to diagnose and treat serious health problems. Ordinary people have 16 times the frequency of visits to the doctor.

- In the eccentric group, the test subjects repeatedly emphasized "how essential humor is for their well-being and self-respect in an increasingly bleak and conformist world."

Weeks speculates on these results with the following assumptions:

- From a purely subjective point of view, eccentrics made a happier and more humorous impression than the control group.

- Without feeling the need to adapt (“personal freedom that we unnecessarily give away”), eccentrics experience less negative stress . By spontaneously, creatively and curiously following your inspirations, you “destroy the breeding ground for neuroses” and experience positive stress (eustress).

- The main communication partner of an eccentric person is himself. "Basically, you are playing a brainstorming game with yourself as the only player."

- When it comes to “the health of the social organism, eccentrics are indispensable” because they bring up a variety of ideas and exemplify behaviors that allow the group to adapt. Absolute behavioral uniformity is detrimental to a social organism. "Eccentrics, seen in this way, are the mutations of social evolution".

thanksgiving

About 70 people are named in the acknowledgments. Special thanks go to Kate Ward, who conducted the majority of the interviews and the fieldwork , and to all the eccentrics who participated in the study "with patience, enthusiasm and ingenuity" and who gave the time for the interviews.

literature

The literature contains about 140 literatures alphabetically listed after the first author, covering the period from the 1950s to the 1980s.

Image sources

Eight references are listed for the 18 illustrations used in the book.

register

The register contains about 300 names, mostly of the eccentrics mentioned in the book.

reception

- In her book In and Out: Eccentricity in Britain , Waltraud Ernst, Professor of Medical History, describes the book and the study as "the only study of eccentricity providing a sustained scientific or psychological approach".

- The Spektrum der Wissenschaft book review states, “Certainly this book is more popular than scientific, more promoting a previously neglected topic as a definitive study of the psychology of the eccentric. One might reproach Weeks for systematic flaws in his method, for example that extroverted eccentrics are overrepresented compared to those who quietly indulge their whimsy to themselves. But he laid the foundation stone for the first time and adequately defined the term eccentric, which according to Weeks can only be found in one of the four standard textbooks on psychiatry and is also missing in my edition of dtv-Brockhaus. "

- Die Zeit writes: “David Weeks has now published the results of the unique psychological study together with the American science author Jamie James in the book 'Eccentrics - about the pleasure of being different' [...]. 'Eccentrics are healthier because they are happier,' Weeks believes in hundreds of interviews. "

- Review at literaturkritik.de: "Weeks and James try to research the phenomenon of the eccentric for the first time using empirical science."

Web links

- David Joseph Weeks website with comments on how research on eccentrics has changed since his study was published.

Explanations and individual evidence

- ↑ In one of four psychology textbooks, Weeks found the definition “predominantly inadequate or passive psychopathy ”.

- ↑ In this context, “normal” is a relative term. Anyone who is characterized today by his behavior as a “normal person” would violate many behavioral norms of the Middle Ages or even today's different cultures.

- ↑ The minimum required for qualification was two independent sources that refer to this person as "eccentric" (or synonyms thereof).

- ↑ Freely translated: "... an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whoever I want, for as long or as short as I can, to change this love every day if I like it!"

- ^ Robert Chambers: Traditions of Edinburgh by Robert Chambers . W. & R. Chambers, 1869, p. 343.

- ↑ K. Randell Jones: In the Footsteps of Davy Crockett . John F. Blair, Publisher, 2006, ISBN 978-0-89587-602-7 , p. 241.

- ^ Brewster Ghiselin: The Creative Process , University of California Press, reissue 1985, ISBN 978-0-520-05453-0 .

- ↑ AJ Durnell and NE Wetherick: The relation of Reported Imagery to cognitive performance , Brit. J. Psychol., Vol. 67, pp. 501-506 (1976), doi: 10.1111 / j.2044-8295.1976.tb01538.x .

- ↑ "Some people say I can't sing, but nobody can say that I didn't sing."

- ↑ Blavatsky's Venusian space travelers lead Weeks to suspect that Erich von Däniken could also have been inspired by her.

- ^ Present State Examination (PSE). Item Group Checklist. Clinical History Schedule. World Health Organization. Assessment, Classification and Epidemiology (2014) ; accessed on February 9, 2017.

- ↑ An occurrence in this category indicates a clearly recognizable symptom.

- ↑ Appearance in this category is not sufficient to infer a clear mental illness, as normal persons occasionally show these symptoms as well.

- ↑ An appearance in this category means without any findings .

- ↑ The following 16 personality factors are examined: Warmth (e.g. feeling good in society), logical reasoning, emotional stability, dominance, liveliness, awareness of rules (e.g. morality), social competence (e.g. sociability), sensitivity, Vigilance (e.g. distrust), aloofness (e.g. closeness to reality), privacy, anxiety, openness to change, self-sufficiency, perfectionism and tension.

- ↑ Extreme persons can show a very different personality spectrum in individual aspects. The percent data does not say that all extreme people have the same personality spectrum.

- ↑ It is mentioned that a number of eccentrics in the study consistently identified with Robin Hood and his way of life.

- ↑ One subject had focused his entire life on potatoes (nutrition, history, socio-political impact, ...).

- ↑ T Hought, L anguage and C ommunication, ie thinking, language and communication.

- ↑ The table only shows results in which one of the two groups achieved at least 4%.

- ↑ The TLC scale was developed by Andreasen as an aid to diagnosing and measuring schizophrenia . The results and distribution patterns found are called "communication disorders". However, eccentrics do not fit into any of these patterns, but differ from normal people occasionally and only in "special features".

- ↑ Weeks mentions two parallel results: (1) In state institutions (“strict, fixed criteria”), men predominate in admission (real problem cases), in private institutions (softer criteria) women predominate (possibly even admission without being required; according to Weeks: "Double standards in psychiatry"). (2) Today nine out of ten husbands leave their alcoholic wives, while only one in ten (dependent) wives leaves their alcoholic husbands.

- ↑ Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby: Life with the Ladies of Llangollen (p. 219), Viking (1984), ISBN 978-0-670-80038-4 .

- ↑ Weeks reports in the chapter Eccentricity and Mental Illness of three confirmed and two unconfirmed married couples in which both partners are eccentrics.

- ^ Oxford Brookes University: Waltraud Ernst ; Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ↑ Loosely translated: The only study of eccentricity that offers a sustainable scientific or psychological approach.

- ^ Waltraud Ernst: Histories of the Normal and the Abnormal: Social and Cultural Histories of Norms and Normativity . Routledge, September 27, 2006, ISBN 978-1-134-20549-3 , p. 99.

- ↑ Book review in Spectrum of Science (September 1, 1997), Michael Groß: Ezentriker. About the pleasure of being different ; Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ↑ Jörg Blech: Praise the Macke: Eccentrics are happier and healthier than “normal” people , Die Zeit, January 17, 1997; Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Frank Müller: Eccentric - The Longing for Being Different , literaturkritik.de, February 2004; Retrieved March 3, 2017.