Francesco Datini

Francesco Datini or Francesco di Marco Datini (* around 1335 in Prato ; † August 16, 1410 ibid) was a Tuscan long-distance trader, banker, cloth producer and speculator. The company he founded and expanded over decades operated primarily in the western Mediterranean, but also in England, Flanders and the Crimea , and ran numerous other companies in a kind of holding company. This structure was particularly preferred by the Tuscan wholesalers, but only a few ventured into banking or even speculation on bills of exchange .

Datini became famous on the one hand through a foundation for the poor in his native Prato, which still exists today, and on the other hand because a large part of his correspondence has been preserved - a total of over 150,000 letters, 11,000 of which are private letters. It is the basis for one of the most important scientific institutes on the economic history of the late Middle Ages - and it enables deep insights into everyday life. Datini was described by Johannes Fried (2009) as “perhaps the most famous medieval merchant”.

Life

Francesco di Marco Datini was born in Prato, Tuscany, in 1335 as one of the four children of Marco di Datino and Monna Vermiglia. Little is known about the parents. They had four children, lived in the Porta Fuia neighborhood, and owned some land near Prato that had been in the family since at least 1218. At least once the father and his son Francesco sold meat in the Prato market.

At the age of 13, the Great Plague made him an orphan. In addition, two of his three siblings died of the plague; their names were Nofri and Vanna. Francesco himself had already had a will drawn up, dated June 1, 1348. He wanted to leave numerous Prateser churches small amounts for the reading of masses for his soul, including San Piero in his native parish Porta Fuia. He himself wanted to be buried in San Francesco in Prato.

Together with his younger brother Stefano, who had also survived, he was initially taken in with a relative for thirteen months. They came under the tutelage of Piero di Giunta del Rosso, a cloth maker and dyer. The brothers actually received the loving reception in the memory of Francesco at Piera di Pratese Boschetti. Then he went to neighboring Florence as an apprentice , where Francesco worked in two shops. The lesson usually consisted of first introducing the boys to sales and the internal organization of the store. A specific organization of teaching as it was later developed did not yet exist.

Avignon

At the age of 15, Datini went to Avignon , where he initially worked as a delivery boy. Soon he was managing a branch of his foster father as a factor . Unlike the apprentices, he was involved in the profits. Like most traders, Datini was not tied to any particular trade. He did good business in Avignon with luxury goods and weapons, and the presence of a large Florentine merchant colony, which had contacts with the papal court as well as with secular potentates, helped him a lot. In addition, she had relationships with the arms manufacturers who were based around Milan , for example . This is why chain mail , gloves, helmets and crossbow bolts appear in the sources .

In 1353 he caught up with his younger brother Stefano, taking on his father's 138 lire legacy. In 1354 Piero di Giunta bought a small house in Prato for his foster son. Practically nothing is known about the next few years, except that Datini stayed in Prato for a few months from April 1359, before returning to Avignon on July 15.

From 1361 he worked in the arms business between Milan and Avignon, together with Niccolò di Bernardo, a nephew of his foster mother and another Tuscan. From 1363 to 1367 he was a partner in his company, but a few years after 1363 he rented a first bottega with his partner , with which the two owned their own shop. They paid the previous tenant Giovanni di Lotta 900 Florin to take over the inventory , and a further 300 as a kind of transfer fee.

Five years later he had already risen to become a partner in various trading companies. In October 1367, for example, he founded the Florentine Toro di Berto, a society that lasted until 1373 - and which flourished especially when the Pope was in Avignon. This Datini-di-Berto society is the first medieval society whose bookkeeping has been almost completely preserved.

In 1367 Datini opened his first own shop in the Loge des Cavaliers on the corner of rue la Mirallerie and la Lancerie (today rue du Puits-des-Bœufs and Place de l'Horloge). In the house there was a warehouse and a shop, a changing table and a tavern. This made his society one of the first to benefit from a papal bull of March 18, 1368, which allowed foreign cloth dealers to settle on the banks of the Sorgue and Durance . The company, which was initially closed for three years, was extended in 1370. However, Datini was the weaker partner here, because of the 2,500 florins that both partners brought in, he had to borrow half from Tuccio Lambertucci, with whom he had previously worked. Lambertucci thus became a silent partner. In addition, the first three years up to 1370 were a difficult phase, since Pope Urban V was not in Avignon, but in Rome . This halved the company's profits and only rose again with the return of the Pope.

In March 1373 Datini took over the management of his own company , which managed without the capital of others. In 1374 he was able to purchase a second house, a bella chasa et boteglia .

From 1376 the situation of the over a thousand Italian merchant colony in Avignon became extremely difficult. This was connected with the intention of the resident Pope to return to Rome, which soon led to conflicts in Italy, in which Florence also became entangled. Although the Florentine colony in Avignon dissolved by 1381, faced with the war, Datini was reluctant to return to Prato. This war cost the Florentines alone two million florins and brought them the papal ban - a catastrophe for the city's trade, which was almost paralyzed. Just two days after the dearly bought peace agreement broke out on June 24, 1378, a revolt of the lower classes, overburdened by war taxes. The Ciompi ruled until August 31st ; Together with other craftsmen in the cloth industry, they demanded a quarter for participation in the government and the formation of new guilds. When no immediate improvement in their living conditions was achieved, cloth production could not be increased as hoped, and the movement fell apart, the uprising collapsed.

Datini, who married Mona Margherita di Domenico Bandini in 1376, a 19-year-old Florentine woman from the lower nobility, could not remain unaffected by these events. Her father, Domenico Bandini, was finally executed as a rebel leader in an earlier revolt in 1360. This, too, may have delayed the return of Datini.

In 1382, shortly before his return to Prato, Datini founded a trading company in Avignon that existed until 1400 and took over its management. He took on Boninsegna di Matteo and Tieri di Benci as partners. Profit and loss were divided in these companies according to the contribution of money shares and the work performed. The longevity of this and other associations should be characteristic of his business activity, as, moreover, of the Tuscan companies as a whole.

Prato

In Prato, part of Florence, where the now wealthy man returned after a 33-day trip in January 1383, he became a member of the Arte della Lana , the wool guild. Only with this membership was he allowed to pursue a corresponding trade and at the same time was able to represent his interests in the city government. There he sat, albeit reluctantly, because he preferred to spend his time on business, on the city council and also became Gonfaloniere della Giustizia . As part of his numerous activities, friend and business contacts developed with Lapo Mazzei (the extensive correspondence between the befriended men was published by Cesare Guasti) and Guido del Palagio, but soon also with the most important Florentine families, such as the Medici , the Tornabuoni, the Pazzi , the Guicciardini, the Alberti and the Paciti. His correspondence with his Tuscan factors expanded greatly, such as to Siena .

Together with his former guardian, the cloth weaver Piero di Giunta and a distant relative, he joined two long-distance trading companies in Pisa (no later than January 1383) and Florence. One was a family trading company, the other a sole proprietorship.

In 1384 a modest wool company was founded in Prato, together with Piero di Giunta del Rosso, a master dyer, with whom he had been associated for a long time, and his son Niccolò, within the Arte della Tinta , the dyers' guild. In 1394, when Piero died, he took in Agnolo, Niccolò's son, as a partner. This connection of kinship and partnership with personal cooperation remained typical of Datini's trade organizations that bought unrefined woolen cloth abroad, especially in England , in order to have it finished in Prato. A company for veils soon joined this company.

In order to give adequate expression to its position in the city, the Datini had a city palace built between 1383 and 1399 between Via Rinaldesca and Via del Porcellatico. Famous painters of the time, such as Niccolò di Piero Gerini (around 1340-1414 / 15), Agnolo di Taddeo Gaddi and Bartolomeo di Bertozzo, decorated him. In front of the house was a garden with roses and violas. There was another building in front of today's entrance, so that what was then owned by far exceeded today's palace in terms of size. Piero di Giunta del Rosso had already acquired the property in 1354. The first, still very modest building cost only 63 lire, 6 soldi. Little by little, more adjoining buildings were bought. Datini calculated the total effort in 1399 to be around 6000 florins.

Florence

Since his business scope had long since exceeded the small town of Prato, whose population also shrank from 26,000 to 8,000 from the beginning of the 14th century to the first quarter of the following, Datini moved to Florence. There he founded a company with Stoldo di Lorenzo and another partner, and in 1388 another company with Domenico di Cambio, which continued until his death. In the same year he became a member of the silk makers' guild. He moved several times within the city, in which he lived almost continuously from 1394. He lived first at Ponte alla Carraia, then in Porta Rossa and Por Santa Maria, and finally in Via Santa Cecilia and in Piazza Tornaquinci. In addition, he traveled restlessly between the most important cities in Italy for his trading empire. In addition, multiple plague outbreaks forced him to leave the city. In 1390 he and his household fled to Pistoia , where he stayed until May 17, 1391.

In 1392 the Florentine company took part in a Genoese company in which the three local partners became managers: "Francesco di Marco, Andrea di Bonanno & Co". At the same time Datini turned his Pisan company into a company in which the Florentine company also owned most of the shares. This Pisan company was able to make its capital available to other companies: a further step towards closer integration.

The following year, the Genoese company set up branches in Barcelona , Valencia and Mallorca . Luca del Sera - he should be one of Datini's executors - now went to Barcelona. In 1394 three other companies were founded in Barcelona, Valencia and Mallorca, with agencies in Ibiza and in San Matteo, a village in Catalonia . Mallorca acquired copper in Venice, which was traded from 1398 via Jewish middlemen southwards via Honein (where they had fled from Mallorca from 1391) to the Tuat in southern Algeria , of which Datini was aware. This trade continued until September 1410, beyond Datini's death, though there was a serious break-in in 1407/08 when one of the caravans - they could contain 8,000 to 12,000 camels - was robbed. While San Matteo became an important wool collecting point, Ibiza was famous for its salt. The local branch was run by Florentines. In general, Datini surrounded himself almost exclusively with Tuscans, if possible from the cities he knew, better still from closer and further relatives.

In 1395 Datini became a member of the Florentine dyers' guild. A year later he converted the Catalan company into the Catalan trading company based in Barcelona or Valencia. The Florentine company again had a majority stake in the capital, its three shareholders in turn managed the three sub-companies. In addition, his sole owner company continued to exist there, taking on a leading role in his company system.

Such an interweaving of contribution shares was to become typical of Datini's society, the threads of which came together in Florence. The individual companies were connected to one another solely through his person or through his capital, which gave him the power to make decisions. Contacts in the most influential Florentine circles benefited his business. At the height of his company, Datini worked in 1398 with an invested capital of 45,500 florins.

In 1399 Datini had to flee again from the plague to Bologna , where he stayed until 1401. There he was able to use the extensive contacts of men who had also fled there, such as Filippo Tornabuoni, Piero Bonciani and Antonio di Niccolò da Uzzano, Bartolomeo Balbani from Lucca or Giovanni di Feo Bracci from Arezzo .

Margherita

Datini's wife, Margherita († 1423), was born in 1357 as the youngest of the seven children of Domenico Bandini, whose property in Florence was confiscated in 1358 as a result of political battles. She married Francesco, who was around forty at the time, at the age of 19, according to other sources at 16 in Avignon, without having been able to bring a dowry into the marriage. The marriage remained childless. In 1380 Monte Angiolini wrote to Datini that this fact represented a great burden after four years, on June 21, 1381 he apologized to Margherita for his interference. The distance between the spouses increased significantly, one of the reasons why there was an extensive correspondence between the two.

She went to Prato with Francesco in 1383, occasionally moving to Florence when Francesco relocated his business there. From there they reached 132 of the 182 received letters from her husband - they reached another 44 from Prato and 6 from Pisa. Margherita lived increasingly in Prato and took care of the expansion of the house and the land, as well as the daily routines in her huge household.

In their correspondence, numerous principles of commercial correspondence were taken to heart, such as the specification of the date of issue, the commissioned messenger, the reference to the last letter, the exact time of acceptance or the note "answered on ...". It is therefore known that at least 61 letters from Francesco and 24 letters from Margherita have been lost, of which we know a total of 248. Time gaps arose mainly because the two lived together in one house, such as in 1393, when they fled to Pistoia from the plague, or 1400–1401, when they went to Bologna for the same reason. Most letters are from the years 1394–1395 and 1397–1399, a phase in which up to three letters were written a day. Datini occasionally dictated his letters, sometimes even having them written in his own way. Margherita had to dictate them because she could not write at first. In addition, if it got too personal, both refer to the fact that the rest of the "a bocca", i.e. verbally, should be discussed, on the other hand, the two address each other with "tu", i.e. "you" when she dictates or . Have written. Of the 182 letters from Francesco, he wrote only 48 recognizable with his own hand. The remaining letters come from 18 different hands (Datini wrote around 7,000 letters in total).

Datini placed countless orders, reprimanded her and gave her instructions, discussed projects with Margherita - and yet she gradually took on the role of confidante and advisor.

This was by no means a matter of course, because Datini had an illegitimate son named Francesco in 1387 by his slave Ghirigora, a child who died in 1388. He had fathered a son as early as 1375, but he also died early, probably after four months. Ghirigora was hastily married while still pregnant. Margherita was outraged, felt humiliated. In 1392 Ginevra was also born, also the daughter of a slave. Margherita's sister Francesca, who was herself a multiple mother, even recommended a charlatan visit her in 1393 so that she could have a child. At the same time, Margherita was apparently suffering from very heavy bleeding and menstrual pain .

Margherita, however, accepted the child after initial rejection and soon took loving care of Ginevra. So she took care of the selection of a wet nurse , the equipment, education and training, which z. B. extended to the procurement of suitable toys and musical instruments. She almost adopted her as her own daughter. The mother, Lucia, was freed and Datini married her to one of his co-workers. She continued to live in Margherita's household and the two even became friends. Ginevra was also married on November 24, 1407 to a colleague named Lionardo, son of Ser Tommaso, her trace is lost in the course of the 1420s. Margherita also took care of an otherwise unknown daughter "Chaterina" of the apparently seriously ill father, but not mentioned in the only letter that mentions the child, around 1398. After the death of her husband, Margherita spent a lot of time with Ginevra and her husband Lionardo in Florence.

Francesco, who constantly tried to control and direct his wife - which accounts for a significant part of the correspondence - for a long time underestimated his wife, who ran a huge construction site and a large family for decades, and received and entertained numerous guests, e. B. Francesco Gonzaga . Her nieces also came into the house and lived there for long periods of time, like Tina, whose education Margherita took care of - and she was supposed to learn to read. Although Margherita could only read simple letters, she was able to represent and dictate very complicated facts - a skill that Francesco did not recognize until 1386. Margherita tried her hand at writing - a first letter in uncertain script dates from 1387 - and in 1396 Ser Lapo Mazzei was amazed at her progress. From 1399 she taught his son to write. In that year she also wrote most of the letters to Francesco herself. As if that were enough to prove her skill, from then on she wrote only one letter in her own hand.

At this time, Francesco and Margherita were living even more distant than before. When Francesca, Margherita's sister, died in 1401, Francesco's friends urged him to at least give his wife some comfort.

Bank formation and speculation

In 1399 Francesco Datini went back to Florence and ventured there to found a bank, together with a Prateser. Such banks had little in common with the simple pawnbrokers, the Lombardi , but they too lent money and were therefore suspected of engaging in usury . Datini's partner Domenico di Cambio said: "Francesco di Marco wants to lose his reputation ... in order to become money changers, among whom there is none who does not engage in usury". Datini became a member of the Arte del Cambio , the guild of changers , on March 4, 1399 . Nevertheless, he avoided getting involved in credit transactions with great ecclesiastical and secular lords. As a result, much larger banks, like those of the Florentine banks of the Bardi and Peruzzi, collapsed in his childhood .

But Datini had long since - in the eyes of contemporaries - advanced on much more reputable terrain. He had started speculative business in which he bet by means of bills of exchange (5000 in total) on exchange rate fluctuations of various currencies, especially between Flanders, Barcelona and Italy. Domenico di Cambio was of the opinion that he would "rather earn 12% in goods transactions than 18% in bills of exchange".

The ascent was almost ruined by a catastrophe in 1400. In another wave of the plague, almost all of his shareholders died, so that he had to close his companies in Pisa and Genoa . The bank in Florence was also closed and the production of wool and silk scarves in Prato was stopped. When Datini returned after a year from Bologna, where he had fled because of the plague, he complained on September 20, 1401 of the loss of his best employees, such as the banking specialist Bartolomeo Cambioni, Niccolò di Piero, who knew production techniques, Manno the Elder 'Albizzo and Andrea di Bonanno, who ran the business in the Pisa and Genoa area. Datini decided to give up the bank and the two production facilities as well as Pisa and Genoa.

Datini largely recovered from this severe blow within a few years, but thought more and more - he expressed this in letters to his friend Ser Lapo Mazzei from Florence - about establishing a charitable foundation. This was obvious insofar as the companies saw themselves obliged to give God a share of the profit, yes, to set up his own account for "Messer Domeneddio". It stood for the poor and was the first to be paid out when a society was dissolved.

Nonetheless, Datini tried to expand his business framework further by trying to initiate business with the Hafsids and the Marinids of Tunisia and Morocco in North Africa . In the trading metropolises of the eastern Mediterranean, such as Venice, he had business partners so that he was informed in good time about political events, prices, goods quality and changing trade customs, about piracy and everything that could influence his business.

Ascent to the Calimala

In 1404, at the age of almost 70, he was accepted into the most important Florentine guild, the cloth finisher's guild (Arte di Calimala) . The trade in cloths of the highest quality was reserved for its members. Trade contacts connected him with more than forty Italian and at least ten French cities, with Bruges and a few other places in the empire , such as Nuremberg , but also with Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and the Levant - with a total of 267 places. 1634 letters from 63 different senders alone reached him. B. from Rome.

testament

After Datini's death on August 16, 1410, his wife Margherita - she died ten years later - and his partner Luca del Sera were appointed executors. The considerable sum of exactly 72,039 florins, 9 soldi and 4 denarii went to a pious foundation at Datini's request. In addition, there was real estate ownership in the estimated amount of 11,245 florins. The Florentine company was to be run for another five years so that its profits could flow into the foundation, which had total assets of more than 100,000 florins. That this sum represented a considerable fortune is made clear by the price information from this period. A pig cost 3 florins, a good riding horse 16 to 20, a slave 50 to 60 florins, a purple robe like the one Datini wore in a painting cost around 80 florins.

Datini's wife arranged everything that was necessary, such as ordering a tombstone from Niccolò di Piero Lamberti (around 1370–1451), which is still in the cathedral today. She made do with a small portion of the property, which allowed her to live an adequate life in the house of the deceased.

The Ceppo de 'poveri Foundation - Ceppo was called a stump into which churchgoers threw their donations for the poor - celebrated its 600th anniversary in 2010. The municipality of Prato still appoints a five-person steering committee and four dignitaries, each of whom represents a district. Since then, this foundation has not only managed Datini's assets for the benefit of the poor Pratos, but also his house and all of his correspondence. Even before Datini was founded, there had been a Ceppo vecchio , the Monte Pugliesi , since 1282 , so that Datini's foundation was soon called Ceppo nuovo .

When Prato was sacked in 1512, the institutions were burdened with a mountain of debt, so that they had to be closed in 1537. However, the two foundations were merged on June 13, 1545 by Cosimo I de 'Medici and resumed their function under the name Casa Pia de' Ceppi . Since then she has been taking care of the poor in the city on the one hand, especially children, and on the other hand she promotes art and art preservation, especially in the church of San Francesco, which Datini was very close to. Extensive restoration work was carried out there in 2010. Before being bagged and walled up under a staircase in the 17th century, the documents that Datini left behind were viewed and sorted one last time in 1560 by Alessandro Guardini, a scholar from Prato.

Datini would probably not have set up this foundation if his friend Ser Lapo Mazzei had not convinced him, whose thinking was strongly influenced by the ideals of the Franciscans. This success is probably also due to Margherita Datini, who also ensured that his work was continued in this sense. She also had paintings put up on the outside walls of the house that recalled the life of the deceased. Some of the houses served the foundation as a hospice for a long time . As early as 1399, Francesco had taken part in the pilgrimage of the Bianchi (the whites), who went barefoot and clad only in white linen from town to town, praying and trying to reconcile their enemies. Datini was also the owner of a copy of Dante's Divine Comedy . He writes that he did not want to starve on his pilgrimage: “And so that we also have everything we need for life, I took my two horses and the riding mule with me; and for these animals we loaded a pair of saddle chests, in which there were many boxes with all sorts of confectionery, and a great deal of wax in the form of little torches and candles, and cheese of all kinds, and fresh bread and biscuits and pretzels, with and without sugar, and more other things that man needs for life, so that the two horses were fully loaded with our provisions; and besides these they carried a large sack of warm robes ... "

The trading empire

Datini's company system reached its greatest expansion for the time being in 1399. It comprised trading companies, banks and production companies, especially for the further processing of semi-finished cloth products. Although he also did business in the eastern Mediterranean, like many of his Tuscan contemporaries, he concentrated his activities largely in the west. The ability to move funds without cash played a decisive role in this decision for the West. With all this, a dense communications network had to be maintained over considerable distances.

Datini founded both sole proprietorships and companies in the western Mediterranean. Either he himself had the majority share in the capital of the respective company, as in Avignon, in both production plants and in the bank, or the company in Florence had the majority of the capital as in the case of the companies in Pisa, Genoa and Catalonia. Since these companies only invested part of their capital in other firms and were only linked by personal union, they could no longer drag each other into bankruptcy .

Datini managed this complex in the form of a kind of holding company in which the company in Florence, without producing itself, held a large share of the capital in the companies it ran - a form of organization that the Medici of the 15th century fully developed. As Maggiore - that's how Datini was called - he personally managed the entire company, represented by his trade mark. With the support of the staff from the Florentine company, he governed down to the most insignificant personnel issues, made his choices, provided training and control, received reports from everyone and incessantly gave written instructions himself. On average, he picked up pen fifty times a day.

According to the organizational form, Datini ran two companies alone, namely in Florence and Prato, plus joint ventures in Avignon, Genoa, Barcelona - with branches in Valencia and Mallorca -, in Pisa, plus two companies in Prato and two in Florence. There were a total of six trading companies, of which he managed one alone, two production companies ( Compagnia della Lana for wool and Compagnia della Tinta for dyeing), a bank, plus the mixing company in Prato, which he personally managed. This alone required extensive correspondence, to which other addressees joined in numerous places. In 1962, Federigo Melis assigned this extensive correspondence to the 280 or so places of the senders and addressees noted in the letters. The vast majority of the correspondence was written in Tuscan , but Datini's archive also contains 2,678 letters in Catalan , and Latin also occurs occasionally, but never within the trading empire, but only in external correspondence and almost exclusively with northern Italian partners. Datini, who certainly spoke Provençal after his long stay in Avignon , received 86 written records in this language. The letters from his Avignon period that have not survived contain numerous documents in Provençal, but they have been lost.

In all companies, the partners, but above all Datini personally, did a large part of the work. Notwithstanding this, each of his companies also had permanently employed factors, notaries , accountants or cashiers, messengers and apprentices who, unlike the companies , the shareholders, did not participate in the profit. The Datini archive contains a contract with Berto di Giovanni, a young man from Prato who worked for Datini for three years, received 15 florins in the first year, 20 in the second and 25 in the third, and all expenses reimbursed . There is also an acknowledgment of receipt of the wages of a young accountant who received twelve florins a year.

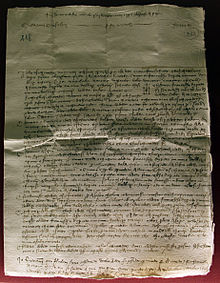

Around 600 accounts books (Libri contabili) of very different types have survived from Datini's possession . They comprehensively reflect the business practice of that time. There was the Quadernacci di Ricordanze , which are nothing more than notebooks in which daily income and expenses were recorded as they were incurred. There were also all sorts of notes, even the latest news from the day in brief. The entries from the Ricordanze were then systematically compiled in the Memoriali . The Libri grandiflora , finally, led every society, namely (since 1382 at the head office and since 1397 in Avignon) in double-entry bookkeeping, were magnificently bound by Francesco in parchment or leather, wore his trademark and were continually with the letters of the alphabet Mistake. According to the custom at the time, the front of the first sheet was almost always headed with a religious sentence such as: "In the name of God and the Blessed Virgin Mary" or "In the name of God and business". In addition, incoming and outgoing books ( libri d'entrata e d'uscita ) were kept, also called debtor and lender books (libri dei debitori e creditori) , in which the incoming and outgoing cash was entered, which in turn was then entered into the Libri d'Entrata e d'Uscita della Cassa grande was summarized.

In Avignon there were cash cassettes in the trading house, which were settled every evening and then emptied into the cassa grande , to which Francesco Datini was the only one who had the key. Then every single trading house kept its books, which contained inventory lists, receipts and waybills, etc.; the partners and factors abroad also kept records and there were also property registers, payrolls and the twelve handbooks of the cloth factory in Prato.

Finally, Datini also kept private accounts and recorded his personal expenses and those for his household in the account books “di Francesco proprio”, while he wrote partnership agreements, accounts that gave information about the respective capital status of each company member, and balance sheets, especially in a Libro segreto , a secret book. The right of the merchant to keep these books closed to public scrutiny was so firmly anchored that a friend of Datini's when the tax officials of the city council of Florence asked to see all the books in 1401 wrote: “The financial plight of the commune compels them to this shamelessness to commit."

Datinis archive

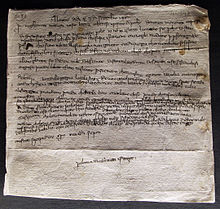

Datini began to keep his papers as early as 1364 in Avignon, but most of the documents date from 1382 to 1410, i.e. the second half of his business life.

The Datini archive is by far the most extensive surviving merchant archive of the Middle Ages. It comprises over 152,000 "items" in 592 folders, including more than 125,000 business letters, around 11,000 private letters and a further 15,802 documents of other kinds. The 574 account books alone, including the main books, form a huge pool. There are also around 300 partnership contracts, mostly contracts from other companies that had a business relationship with Datini's company. After all, the archive contains around 5,000 bills of exchange in addition to a large number of other documents. Even after his death, the ongoing correspondence ended up in the archive; the transmission only stopped in 1422.

All these documents are to this day in the former house of Francesco and Margherita Datini in Prato in Via Lapo Mazzei - a name that was of great importance for Datini because he was a close friend and trustworthy advisor. The upper floor is still largely in its original condition. Shortly after 1410, the foundation added heavily faded paintings today. The windows on the ground floor were only changed in the 17th century as part of a renovation.

When all the furnishings were removed from the house in the 17th century in order to renovate the house, Datini's "papers" were also torn from the cupboards and deposited under a staircase in the house. There they were forgotten until 1870.

Scientific importance

The real rediscoverer of the papers was Archdeacon Don Martino Benelli from Prates, who in 1870 sorted the documents sewn into sacks with the help of Don Livio Livi. Initially, the holdings were moved to the bishop's residence during the restoration of the Datini house. Livi made the archive better known through publications, by publishing in the specialist journal Archivio Storico Italiano around 1903 . On the 500th anniversary of his death in 1910, a pamphlet on Datini appeared under the auspices of his foundation. In 1915, Sebastiano Nicastro published an extensive inventory in a series on Italian archives. In 1927 Datini's will was published.

The work on banking and bills of exchange that Raymond de Roover presented at the end of the 1940s, and in which documents from Datini's archive appeared, first put the importance of the Prateser entrepreneur on a level that extended beyond Italy's borders. Outstanding popular scientific works, especially the biography first published in 1957 by Iris Origo in London, made Datini and the merchant spirit of his time known beyond specialist circles.

It was not until 1958, on the occasion of an international exhibition with the participation of Soviet scientists - after all, Datini's trade relations had extended to Crimea - and chaired by former President Luigi Einaudi , that it was agreed to return the holdings to their original location. The Ministry of the Interior , to which all archives in Italy were subordinate until 1975 - today they are assigned to the Ministry of Cultural Assets and Tourism - ordered that a branch of the Florentine State Archives should be set up, which soon became autonomous. In the same year Guido Pampaloni published an inventory.

Federigo Melis and Armando Sapori , who disagreed about the importance of Datini's holding, caused numerous, initially mainly Italian, scientists to search the archives with a view to their research areas. The holdings emerged not only in urban history studies, but also in thematically more focused works such as Raymond de Roover's history of money, banking and credit. In the meantime there is hardly a question about medieval economic history in which Prateser archives do not play a role. The spectrum ranges from questions of the history of mentality to meticulous detailed studies of the internal functioning of such a company. But the questions have now grown far beyond this and do not directly affect fields of economic history such as writing, the history of the sexes, regulatory behavior, medicine, etc.

In addition, the holdings were used as an opportunity to found their own research institute, the Istituto di storia economica "Francesco Datini" , which annually organizes lecture and discussion weeks on changing topics and generously supports research on the holdings. The XLII. Settimana di Studio , a week of research and study that took place in Prato from April 18-22, 2010, was devoted to the question of where economic history is developing. As early as 1979 the bones of Datini were examined from an anthropological point of view.

The institute in Via L. Muzzi 38 is not only strongly anchored scientifically, but also in the city of Prato itself. On August 17, 2007, the city celebrated the 597th anniversary of Datini's death in a big celebration. The Gonfalone del Comune laid a wreath on his monument. Datini had determined in his will that a mass should take place on the day after his death, along with a public honor. His tombstone, which was restored in the 1990s, is also cared for. In 2010, the 600th anniversary of Datini's death, extensive memorial services were held. The Italian Post issued a special postage stamp. The Datini palace has been restored.

Literature and Editions

Overarching, primarily biographical work

- Giampiero Nigro (Ed.): Francesco di Marco Datini. The Man, The Merchant , Firenze University Press, Fondazione Istituto Internazionale di Storia Economica "F. Datini", Florence 2010.

- Robert Brun: A Fourteenth-Century Marchant of Italy: Francesco Datini of Prato , in: Journal of Economic Business History (1930) 451-466.

- Robert Brun: Annales avignonnaises de 1382 à 1410 extraites des archives Datini , in: Mémoires de l'institut historique de Provence 12 (1935) 17–142.

- Cassandro Michele: Aspects of the Life and Character of Francesco Di Marco Datini , in: Giampiero Nigro (Ed.): Francesco di Marco Datini. The Man, The Merchant , Firenze University Press, Fondazione Istituto Internazionale di Storia Economica "F. Datini", Florence 2010, pp. 3-51.

- Michele Luzzati: Datini, Francesco. In: Massimiliano Pavan (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 33: D'Asaro – De Foresta. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1987, pp. 55-62.

- Iris Origo : "In the name of God and of business." Life picture of a Tuscan merchant of the early Renaissance, Francesco di Marco Datini (1335–1410) , translated into German by Uta-Elisabeth Trott, CH Beck, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-406-30861 -9 .

- Joseph Patrik Byrne, Eleanor A. Congdon: Mothering in Casa Datini , in: Journal of Medieval History 25/1 (1999) 35-56.

- Elena Cecchi: Le lettere di Francesco Datini alla moglie Margherita (1385-1410) , Prato 1990.

- Ann Crabb: Ne pas être mère: l'autodéfense d'une Florentine vers 1400 , in: Clio. Histoire, Femmes et Sociétés 21 (2005), publ. in June 2007. ( Online, accessed November 17, 2014 )

- Ann Crabb: "If I could write": Margherita Datini and letter writing, 1385-1410 , in: Renaissance Quarterly 60 (2007) 1170-1206.

- Valeria Rosati (ed.): Le lettere di Margherita Datini a Francesco di Marco (1384-1410) , Cassa di risparmi e depositi, Prato 1977 (Biblioteca dell'Archivio Storico Pratese, 2).

- Diana Toccafondi, Giovanni Tartaglione (ed.): Per la tua Margherita… Lettere di una donna del '300 al marito mercante. Margherita Datini e Francesco di Marco 1384–1401 , CD-ROM, Archivio di Stato di Prato, Prato 2002.

- Cesare Guasti: Ser Lapo Mazzei. Lettere di un notaro ad un mercante del secolo XIV , 2 vols., Florence 1880.

- Veronica Vestri: Appunti per una storia istituzionale della Casa Pia dei Ceppi dal secolo XIV al secolo XIX , in: Una casa fatta per durare mille anni , Polistampa, Prato 2012.

- Armando Sapori : Cambiamenti di mentalità del grande operatore economico tra la seconda metà del Trecento ei primi del Quattrocento , in: Studi di Storia economica (1967) 457-485.

- Veronica Vestri: Istituzioni e vita sociale a Prato nel primo quattrocento , laurea , Florence 1993, Prato 1994.

Inventory, archive and Palazzo Datini

- Elena Cecchi Aste: L'Archivio di Francesco di Marco Datini. Fondaco di Avignone. Inventario , Rome 2004.

- Anne Dunlop: "Una chasa grande, dipinta": Palazzo Datini in Prato , in: Dies .: painted palaces. The Rise of Secular Art in Early Renaissance Italy , Penn State Press 2009, pp. 15-41.

- Sara Catharine Ellis: The Late Trecento Fresco Decoration of the Palazzo Datini in Prato , thesis, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario 2010 ( online , PDF)

- Jérôme Hayez, Diana Toccafondi (eds.): Palazzo Datini a Prato. Una casa fatta per durare mille anni , Polistampa, Florence 2012.

Use of script and internal organization

- Franz-Josef Arlinghaus : 'Io', 'noi' and 'noi insieme'. Transpersonal concepts in the contracts of an Italian trading company of the 14th century ( online RTF )

- Franz-Josef Arlinghaus: Between note and balance. On the momentum of the use of writing in commercial accounting using the example of Datini / di Berto-Handlungsgesellschaft in Avignon (1367–1373) , Diss. Masch. Münster 1996, Frankfurt 2000 ( partially online ).

- Hans-Jürgen Huebner, Ludolf Kuchenbuch : writing, money and time. Francesco Datini's letter of exchange dated December 18, 1399 in the context of his bookkeeping , in: Old European written culture, course unit 5: From the Bible to the library. Seven case studies on the profile and development of the written culture in the Middle Ages , FernUniversität Hagen 2004, pp. 115–137.

Economic organization and its means

- Enrico Bensa : Francesco di Marco da Prato. Note and documenti sulla mercatura Italiana del secolo XIV , 2 volumes, Milan 1928.

- Markus A. Denzel : La Practica della Cambiatura. European payment traffic from the 14th to the 17th century , Stuttgart 1998.

- Gaetano Corsani : I fondaci ei banchi di un mercante pratese del Trecento , Prato 1922.

- Bruno Dini: Una pratica di mercatura in formazione (1394-1395) , Florence 1980.

- Luciana Frangioni: L'azienda trasporti di Francesco Datini (con trascrizione del relativo quaderno del 1402) , in: Studi di Storia Medioevale e di Diplomatica 7 (1983) 55-117.

- Marco Frittajon, Georgios Korakakis, Massimiliano Gaiatto, Manuel Gerardi: Organizzazione della produione del commercio (sec.XIV-XVI) , website of the Università Ca 'Foscari, Venice ( Memento of January 23, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- Federigo Melis : Il problema Datini. Una necessaria messa a punto , in: Nuova Rivista Storica (1966) 682-709.

- Federigo Melis: L'archivio di un mercante e banchiere del Trecento: Francesco di Marco Datini da Prato , in: Moneta e Credito 7 (1954) 60-69.

- Raymond de Roover : Money, Banking and Credit in Mediaeval Bruges. Italian Merchant-Bankers, Lombards, and Money Changers. A Study in the Origins of Banking , Cambridge / Mass. 1948.

- Victor I. Rutenburg: Tre volumi sul Datini. Rassegna bibliografica sulle origini del capitalismo in Italia , in: Nuova Rivista Storica 50 (1966) 666–681.

Non-Tuscan branches and companies

- Francesco Bettarini: La comunità pratese di Ragusa (1414-1434). Crisi economica e migrazioni collettive nel tardo medioevo , Leo S. Olschki, Florence 2012.

- Michele Cassandro: Il Libro giallo di Ginevra della compagnia fiorentina di Antonio della Casa e Simone Guadagni. 1453-1454 , Florence 1976.

- Elena Cecchi Aste: Il carteggio di Gaeta nell'archivio del mercante pratese Francesco di Marco Datini, 1387-1405 , Gaeta 1997.

- Martin Malcolm Elbl: From Venice to the Tuat: Trans-Saharan Copper Trade and Francesco di Marco Datini of Prato , in: Money, Markets and Trade in Late Medieval Europe. Essays in Honor of John HA Munro , Brill, Leiden 2007, pp. 411-459.

- Luciana Frangioni: Milano fine Trecento. Il carteggio milanese dell'Archivio Datini di Prato , Opus libri, Florence 1994.

- Ingrid Houssaye Michienz: Datini, Majorque et le Maghreb (14e-15e siècles). Réseaux, espaces méditerranéens et stratégies marchandes , Ph.D, Florence 2010, Brill, Leiden 2013. ISBN 9789004232891

- Giampiero Nigro: Mercanti in Maiorca. Il carteggio datiniano dall'isola (1387-1396) , Florence 2003ff.

- Christiane Villain-Gandossi: Les salins de Peccais au XIVe siècle, d'après les comptes du sel de Francensco Datini , in: Annales du Midi 80 (1968) pp. 328-336.

Patronage, piety

- Joseph Patrik Byrne: Francesco Datini, "father of many". Piety, Charity and Patronage in Early Modern Tuscany , Diss. 1989, Indiana University, Bloomington 1995.

- Simona Brambilla (ed.): "Padre mio dolce". Lettere di religiosi a Francesco Datini. Antologia , Rome 2010 (Letters of the Religious; Letter 1-204, pp. 1–281, Letters 205-220 by Datini; pp. 283–323, 28 plates). ( online , PDF)

Web links

- Institute for Economic History "Francesco Datini" in Prato

- Biography of Datini on the institute's website

- Website of the Prato State Archives ( archive version from December 3, 2012 ( memento from December 3, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) in German)

- The Wills and Codicils of Marco (1348) and Francesco di Marco (1410) Datini , translated into English by Joseph Patrik Byrne

- Literature by and about Francesco Datini in the catalog of the German National Library

- Archivio Datini. Corpus lemmatizzato del carteggio Datini (Italian, English, French)

- Simonetta Cavaciocchi: Il Palazzo Datini. La Dimora , Prato State Archives

- Stefan Finsterbusch: The treasure on the cellar stairs , in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, July 26, 2015

Remarks

- ↑ Federigo Melis counted over 152,000 letters (F. Melis: Aspetti della vita economica medievale , Siena 1962, pp. 30–32.)

- ↑ The tradition is far from complete. Datini received and kept around 6,000 letters from Venice , but only a few dozen counter- letters have survived (cf. Eleanor Congdon: Datini and Venice. News from the Mediterranean Trade Network , in: Dionisius A. Agius, Ian Richard Netton (eds.) : Across the Mediterranean Frontiers. Trade, Politics and Religion, 650-1450 , Turnhout: Brepols 1997, pp. 157–171, here: pp. 161f.)

- ^ Johannes Fried: The Middle Ages: History and Culture , Munich, 3rd edition 2009, p. 401.

- ^ John Reader: Cities , London: William Heinemann 2004, p. 93.

- ↑ In English translation by Joseph Patrick Byrne: The Black Death , Westport, Connecticut 2004, pp. 170f. Now also available digitally .

- ↑ Luciana Frangioni: Armi e mercerie fiorentine per Avignone, 1363-1410 , in: Studi di storia economica toscana nel Medioevo e nel Rinascimento in memoria di Federigo Melis, Pisa 1987, pp. 145-171.

- ^ Enrico Bensa: Francesco di Marco da Prato , Milan 1928, p. 75.

- ↑ The focus of the work of Franz-Josef Arlinghaus lies on this stock : From the note on the balance sheet , which has been partially published, but with a different title (see literature).

- ↑ Michel Hayez: Éviter la récession économique, souci des papes Urbain V et Grégoire XI au départ d'Avignon, in Avignon au Moyen Âge, textes et documents , Avignon 1989, p. 97f.

- ↑ Federigo Melis : Aspetti della vita economica medievale , Siena 1962, pp. 135ff.

- ↑ La firma is the signature in Italian today. In the commercial area, this emerged from the dealer symbol, usually in connection with a cross. A general term for a company did not yet exist, but the term “company”, which emphasizes the role of the head of the company, is used in research. The modern term “company” feigns a supra-personal continuity that has rarely existed in this way. If they existed, as in the case of the family companies in Venice (see the economic history of the Republic of Venice ), then it was on the basis of close relationships among brothers who were considered partners without a contract.

- ↑ Datini's archive forms the most important basis for the research of the Florentine trading company of Tornabuoni up to 1410, which concentrated primarily on wool and fabrics, but whose activities cannot be fully represented for this phase, cf. Eleonora Plebani: I Tornabuoni. Una famiglia fiorentina alla fine del Medioevo , FrancoAngeli, 2002, p. 27. Simone Tornabuoni wrote Datini for the last time in November 1393.

- ↑ Jérôme Hayez: Un facteur siennois de Francesco de Marco Datini: Andrea di Bartolomeo di Ghino et sa correspondance (1383-1389) , in: Bollettino / Opera del Vocabolario italiano 10 (2005) 204–397.

- ↑ The Prato State Archives give an idea of the documents .

- ↑ St. Christophorus is well preserved , but also "Speranza e Prudenza" . A concise biography in the Grove Dictionary of Art .

- ↑ Bruce Cole: The interior decoration of the Palazzo Datini in Prato , in: Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz 13 (1967) 61-82 and Ders .: The interior decoration of the Palazzo Datini in Prato , in: Studies in the History of Italian Art, 1250-1550, Ed. B. Cole, London 1996, 1-22.

- ↑ Here is a floor plan of the building .

- ↑ In 1910, the reconstruction of the external appearance of the palace came to the following conclusion ( memento of May 19, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Massimo Livi Bacci Europe and its people. A population history , Munich: Beck 1999, p. 10 (ital. Bari: Laterza 1998).

- ↑ Around 1390 a painting was created that depicts Datini. It comes from Tommaso di Piero del Trombetto. A picture can be found here .

- ↑ On Datini's business activities in Barcelona cf. Maria Elisa Soldani. Uomini d'affari e mercanti toscani nella Barcellona del Quattrocento , o. O., 2010; especially pp. 364–374.

- ↑ José Bordes García: Il commercio della lana di 'San Mateo' nella Toscana del Quattrocento: le dogane di Pisa , in: Archivio Storico Italiano 165 (2007) 635–664.

- ↑ Datini's trade in African goods via Mallorca has long been underestimated. Cf. Martin Malcolm Elbl: From Venice to the Tuat: Trans-Saharan Copper Trade and Francesco di Marco Datini of Prato , in: Money, Markets and Trade in Late Medieval Europe: Essays in Honor of John HA Munro , Leiden: Brill, 2007 , Pp. 411–459, here: p. 434. The basic source edition is Giampiero Nigro: Mercanti in Maiorca. Il carteggio datiniano dall'isola (1387-1396), 3 vols., Florence: Le Monnier 2003.

- ^ Christiane Villain-Gandossi: Comptes du sel (Libro di ragione e conto di sale) de Francesco di Marco Datini pour sa compagnie d'Avignon, 1376-1379 , Paris 1969 (on the salt of Pecais ).

- ^ Jérôme Hayez: Le rire du marchand. Francesco di Marco Datini, sa femme Margherita et les “gran maestri” florentins , in: La famille, les femmes et le quotidien. XIVe-XVIIIe siècles. Textes offerts à Christine Klapisch-Zuber , eds. I. Chabot, J. Hayez, D. Lett, Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne 2006.

- ^ Richard A. Goldthwaite: The Economy of Renaissance Florence , The Johns Hopkins University Press 2009, pp. 78f.

- ^ Roberto Greci: Francesco di Marco Datini a Bologna (1400-1401) , in: Rendiconti e atti dell'Accademia delle scienze dell'Istituto di Bologna. Classe di scienze morali LXVII (1972-1973) pp. 133-219 and Ders: Il soggiorno bolognese di Francesco di Marco Datini , in: Ders. Mercanti, politica e cultura nella società bolognese del basso Medioevo , Bologna 2004, pp. 171–268.

- ^ Bruno Dini: Nuovi documenti su Giovanni di Bernardo di Antonio da Uzzano , in: Studi dedicati a Carmelo Trasselli , ed. G. Motta, Soveria Mannelli 1983, pp. 309–329.

- ↑ Joseph Patrik Byrne, Eleanor A. Congdon: Mothering in the Casa Datini , in: Journal of Medieval History 25.1 (1999) pp. 35–56, here: p. 39, she was only 16 years old.

- ↑ This and the following mainly based on Elena Cecchi: Le lettere . For historiography cf. Joseph Patrik Byrne: Crafting the Merchant's Wife's Tale: Historians and the domestic rhetoric in the correspondence of Margherita Datini , in: Journal of the Georgia Association of Historians (1996), pp. 1-17.

- ↑ The Datini Institute put the letter of January 16, 1386 online .

- ↑ Eleanor Congdon translated the letter from Mona Piera on the occasion of this event into English. See Katherine L. Jansen, Joanna Drell, Frances Andrews: Medieval Italy. Texts in Translation , University of Pennsylvania Press 2010, p. 441.

- ↑ Katherine L. Jansen, Joanna Drell, Frances Andrews: Medieval Italy. Texts in Translation , University of Pennsylvania Press 2010, pp. 444f.

- ↑ For more details cf. Joseph Patrik Byrne, Eleanor A. Congdon: Mothering in the Casa Datini , in: Journal of Medieval History 25.1 (1999) 35-56 ( online ( Memento of the original from 10 August 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. , PDF). According to her, Margherita was not born until 1360 (p. 36).

- ↑ Ingrid Houssaye Michienzi: Les efforts of compagnies Datini pour établir des relations avec les pays du Maghreb, fin XIVe-XVe siècle debut , in: Relazioni economiche tra Europa e mondo Islamico secc. XIII-XVIII. Atti delle Settimane di Studi 38, Fondazione Istituto internazionale di Storia economica "F.Datini", 1.-5. May 2006, Ed. S. Cavaciocchi, Florenz 2007, pp. 569-594.

- ↑ On writing from Provençal cities: Cesarina Donati: Lettere di alcuni mercanti provenzali del '300 nell'Archivio Datini , in: Cultura neolatina: Bollettino dell'Istituto di filologia romanza 39 (1979) 107–161.

- ^ Karlfriedrich Gruber: Nicholaio Romolo da Noribergho. A contribution to the Nuremberg trading history of the 14./15. Century from the Archivio Datini in Prato (Tuscany) , in: Mitteilungen des Verein für Geschichte der Stadt Nürnberg 47 (1956) 416-425.

- ^ Arnold Esch : La fine del libero comune di Roma nel giudizio dei mercanti fiorentini: lettere romane degli anni 1395-1398 nell'Archivio Datini , in: Bullettino dell'Istituto storico italiano per il Medioevo e Archivio Muratoriano 86 (1976-77) 236 -277.

- ↑ A portrait of Piero and Antonio Miniati of her has also come down to us .

- ↑ Jacob Soll: The Reckoning. Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations , New York 2014, p. 16.

- ↑ Finally on Ceppo cf. Paolo Nanni: L'ultima impresa di Francesco Datini. Progettualità e realizzazione del “Ceppo pe 'poveri di Cristo” , in: Reti Medievali Rivista 17.1 (2016) 281-307.

- ^ Archivio Datini .

- ^ Tommaso Franchi: L'influenza francescana nei consigli di ser Lapo Mazzei e nelle disposizioni d'ultima volontà di Francesco di Marco Datini , in: Archivio storico pratese VI (1926) 89-95.

- ^ Joseph P. Byrne: The Merchant as Penitent: Francesco Datini and the Bianchi Movement of 1399 , in: Viator 20 (1989) 219-231.

- ↑ Quoted from: Michael Matheus (Ed.): Pilgrims and Pilgrimage Sites in the Middle Ages and Modern Times , Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1999, p. 8.

- ↑ How far his scope of action extended is shown by the spatial extent of his correspondence on a map of the Datini Institute or the alphabetical list of the locations .

- ↑ In addition: Luciana Frangioni: I costi del servizio postale alla fine del Trecento , in: Aspetti della vita economica medievale. Atti del Convegno di studi nel X anniversario della morte di Federigo Melis, Florence, Pisa, Prato, 10.-14. March 1984, Florence 1985, pp. 464-474 and Dies: Organizzazione e costi del servizio postale alla fine del Trecento. Un contributo dell'Archivio Datini di Prato , Prato: Istituto di studi storici postali 1983.

- ↑ Angela Orlandi (ed.): Mercanzie e denaro: la corrispondenza datiniana tra Valenza e Maiorca (1395-1398) , Valencia 2008.

- ^ Giampiero Nigro: Mercanti in Maiorca. Il carteggio datiniano dall'Isola, 1387-1396 , Florence: Le Monnier 2003 and Angela Orlandi (ed.): Mercanzie e denaro: la corrispondenza datiniana tra Valenza e Maiorca (1395-1398) , Valencia 2008. Review: David Abulafia: Commerce and the Kingdom of Majorca: 1150-1450 , in: Iberia and the Mediterranean World of the Middle Ages. Studies in Honor of Robert I. Burns, Leiden a. a .: Brill 1996, pp. 345-377.

- ↑ There are only a few places where there are studies such as Guido Bandini: Lettere datiniane pervenute dalla Sardegna , in: Annali della Facoltà di Economia e commercio dell'Università di Cagliari 1 (1959-60) 193-211 or Helen Bradley: The Datini Factors in London, 1380-1410 , in: DJ Clayton, RG Davies, P. McNiven, A. Sutton (Eds.): Trade, Devotion and Governance. Papers in Later Medieval History , Phoenix Mill / Washington 1994, pp. 55-79.

- ↑ Federigo Melis, Aspetti della vita economica medievale (studi nell'Archivio Datini di Prato), Siena 1962, prospetto III, now digital: Carteggio Datini - Località mittenti e destinatarie .

- ↑ Josh Brown: Multilingual merchants: the trade network of the 14th century Tuscan merchant Francesco di Marco Datini , in: Esther-Miriam Wagner, Bettina Beinhoff, Ben Outhwaite (eds.): Merchants of Innovation. The Languages of Traders , de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2017, pp. 235–251.

- ^ Giovanni Livi: L'archivio di un mercante toscano del secolo XIV. (Francesco di Marco Datini) , in Archivio storico italiano LXI (1903) 425-431.

- ↑ Giovanni Livi: Dall'archivio di Francesco Datini, mercante pratese, celebrandosi in Prato addi XVI d'Agosto MDCCCCX auspice la casa de pia 'Ceppi il V. centenario della morte di lui , Lumachi, Florence 1910th

- ^ Sebastiano Nicastro: L'Archivio di Francesco Datini in Prato. Inventario , in: Gli archivi della storia d'Italia , p. II, Vol. IV, Eds. G. Mazzantini, G. degli Azzi, Rocca San Casciano: Cappelli 1915, pp. XXIV-76.

- ^ Renato Piattoli: Il codicillo del testamento di Marco Datini , in: Archivio storico pratese VII (1927) 20-22.

- ↑ Guido Pampaloni: Inventario sommario dell'Archivio di Stato di Prato , Florence, Empoli 1958.

- ↑ Klaus Bergdolt : Medical Matters in Correspondence by Francesco Datini (1335–1410), businessman from Prato , in: Würzburger medical historical reports 7 (1989) 35–43.

- ↑ A list of the Atti of the Settimane di Studio can be found here .

- ↑ Elena Cristina Lombardi Pardini: Le ossa di Francesco Datini , in: Archivio per l'antropologia e la etnologia, 109–110 (1979–1980) 435–448.

- ^ Giampiero Nigro, Isabella Lapi Ballerini, Daniela Valentini, Veronica Vestri : Una lapida di marmo bianca. Il restauro della pietra tombale di Francesco Datini nel S. Francesco di Prato , Prato 1995.

- ↑ The festival program of the city of Prato can be found here .

- ↑ In January 2011, the long-time restorer Svitlana Claudia Uluvko died ( Morta la restauratrice di palazzo Datini , in: Il Tirreno, January 12, 2011).

- ↑ Review by Patrizia Sardinaa in: Al-Masāq: Journal of the Medieval Mediterranean 27.3 (2015) 307–309.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Datini, Francesco |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Datini, Francesco di Marco |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian merchant |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1335 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Prato (Tuscany) , Italy |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 16, 1410 |

| Place of death | Prato (Tuscany) |