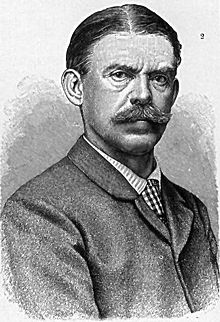

Georg Schweinfurth

Georg August Schweinfurth (born December 17 . Jul / 29. December 1836 greg. In Riga , Governorate of Livonia , Russian Empire ; † 19th September 1925 in Berlin ) was a Russian- Baltic German explorer . Its official botanical author's abbreviation is “ Schweinf. "

Life

His ancestors came from Wiesloch , he himself was born in Riga and grew up strictly pietistic . Schweinfurth studied from 1856 to 1862 in Heidelberg , Munich and Berlin a . a. Botany and paleontology . From 1863 to 1866 he traveled to Egypt and South Sudan as well as the Azande and Mangbetu regions in the Congo as a companion to Arab - Nubian ivory traders (demarcation of the Nile region in the southwest). He lost an eye in a shipwreck in the Congo near Kisangani .

In 1867 he was elected a member of the Leopoldina . Since 1882 he was a corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences .

On August 15, 1868, Schweinfurth began his third trip to Africa in Suez . On behalf of the Humboldt Foundation in Berlin , he traveled from Khartoum up the Nile to Faschoda and the Jur region in 1869 . Advancing further and further with slave hunters, he traversed the countries of the Bongo , Schilluk , Nuer and the Dinka , undertook a trip to what he believed to be cannibalist Niam-Niam , visited the land of the Mittu and Madi and discovered the land of the hitherto unknown in 1870 (also anthropophagous ) Monbutto ( Mangbetu ) the Uelle river ( Uelle-Makua ( Ubangi )). He also won certain information from the dwarves of Akka , from whose circle he, a man named Adimukuh, who described himself as Akka for later education took, which, however, in late summer 1871 in Berber of dysentery died. After overcoming the greatest difficulties, he arrived safely in Khartoum in July 1871, from where he reached the port of departure in Suez on October 4, 1871.

From 1873–1874 Schweinfurth traveled to the Libyan desert and Lebanon. "The results he achieved in ethnography, botany and geography are therefore among the most important things that have ever been achieved on African soil," said Friedrich Embacher in 1882 about the work In the Heart of Africa . Indeed, his work was very influential.

In 1875 he founded the Geographical Society in Cairo and found support in Alexandria from Johannes Schiess . In 1889 Schweinfurth moved to Berlin in order to permanently establish his botanical collections there, which he repeatedly enriched with new research trips in the following years.

Schweinfurth remained a bachelor. He published and compiled collections that are still used scientifically today. His main work was "In the heart of Africa". From 1872 he was a member and from 1906 an honorary member of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory . He was an honorary member of the Thuringian-Saxon Association for Geography.

In addition, he was active in colonial politics and in 1887 a member of the German Colonial Society . In doing so, he influenced the acquisition and organization of German colonies and, in lectures such as 1887, immediately called for the conquest.

Schweinfurth was buried in the Botanical Garden in Berlin. His grave was later declared an honorary grave of the city of Berlin , and it retained this status until 2009. Several streets in German cities are named after him.

Critical reception

As early as 1885 Schweinfurth was accused of using his travelogues, especially the extensive descriptions of cannibalism, to remove the ground from philanthropic attitudes and "doubtfulness". Paola Ivanov even considered it to be the main reason that the Azande cannibalism was taken for granted for a long time. Schweinfurth took over their designation as "Numniam" from the Dinka , who apparently saw them as cannibals or wanted to denigrate them as such. In 2001 Susan Arndt, Heiko Thierl and Ralf Walther went so far as to say that cannibalism could not be proven in Africa in a single case. Schweinfurth himself understood, although he names the doubts and exaggerations of his contemporaries (here the “Nubians”) and above all the alleged cannibals himself, to brush them aside with a kind of superior western colonial knowledge: “The Nubians even want to know that here and since porters who died and were buried on the way have been brought from their graves. Some of the Niamniam, on the other hand, asserted that in their home there was so much loathing of man-eating that everyone refused to eat from a bowl with a cannibal. "And he continues:" Of all known peoples of Africa whose cannibalism is established , the fans ... on the equatorial west coast seem to be related to Niamniam in more ways than one. "

Taxonomic honor

The plant genus Schweinfurthia A. Braun of the plant family of the plantain family (Plantaginaceae) and Schweinfurthafra Kuntze of the family of the mallow family (Malvaceae) was named in his honor. Schweinfurth was one of the first to describe regional differences between chimpanzees in the west and east of the African continent. That is why the East African chimpanzee or long-haired chimpanzee ( Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii ), a subspecies of the common chimpanzee , bears his name.

Writings and works

- Contribution to the flora of Ethiopia Georg Reimer, Berlin 1867 online at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek digital

- Reliquiae Kotschyanae Georg Reimer, Berlin 1868 online at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek digital

- Linguistic results of a trip to Central Africa Wiegandt & Hempel, Berlin 1873

- In the heart of Africa FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1874 Part 1 at archive.org Part 2 online at archive.org

- Artes Africanae. Illustrations and descriptions of productions of the industrial arts of Central African tribes . Brockhaus [u. a.], Leipzig 1875 ( digitized version )

- Discours prononcé au Caire à la séance d'inauguration le 2 juin 1875 Soc. Khédiviale de Géographie, Alexandria 1875

- Abyssinian plant names in: Treatises of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin, pp. 1–84, 1893

- Types of vegetation from the colony of Eritrea Vegetationsbilder 2nd row, issue 8 (1905) online at archive.org

- Arabic plant names from Egypt, Algeria and Yemen Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), Berlin 1912 online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library

- On untrodden paths in Egypt Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1922

- African sketchbook German book community, Berlin 1925

literature

- Georg Schweinfurth: In the heart of Africa 1868–1871 . Erdmann, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-522-60450-4 .

- Manfred Kurz: The Africa explorer Georg August Schweinfurth (1836–1925). In memory of his 150th birthday , in: Kraichgau 10, 1987, pp. 125-131.

- Christoph Marx: The Africa traveler Georg Schweinfurth and cannibalism. Considerations for dealing with encounters with foreign cultures. In: Wiener Ethnologische Blätter 34, 1989, pp. 69–97.

- Ursula von den Driesch: Schweinfurth, Georg August. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0 , p. 50 f. ( Digitized version ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Georg Schweinfurth in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Georg Schweinfurth in the German Digital Library

- Baltic Historical Commission (ed.): Entry on Georg Schweinfurth. In: BBLD - Baltic Biographical Lexicon digital

- Newspaper article about Georg Schweinfurth in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Works by Georg Schweinfurth in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Search for "Georg Schweinfurth" in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Author entry and list of the described plant names for Georg Schweinfurth at the IPNI

- Website Georg Schweinfurth - Expedition

- Rabe K. & Kilian N. 2011: Georg Schweinfurth: Collection of botanical drawings in the BGBM at the BGBM Berlin-Dahlem

- Georg Schweinfurth archive , Koninklijk museum voor Midden-Afrika

Individual evidence

- ^ Member entry by Georg Schweinfurth at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on June 26, 2016.

- ^ A b Franz Wallner: Nature and Ethnology. A new Africa wanderer. In: Neue Freie Presse , Abendblatt, No. 2597/1871, November 16, 1871, p. 4, top left. (Online at ANNO ). .

- ^ Directory of the members of the Thuringian-Saxon Geography Association on March 31, 1885 ( Memento from December 1, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Michael Schubert: The black stranger: the image of the black African in the parliamentary and journalistic colonial discussion in Germany from the 1870s to the 1930s. Steiner, Stuttgart 2001, p. 96, note 111.

- ^ Matthias Fiedler: Between adventure, science and colonialism: the German Africa discourse in the 18th and 19th centuries. Böhlau, Cologne 2005, p. 100.

- ↑ Schweinfurth in the list of honors of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein

- ^ Wilhelm Schneider: The primitive peoples, misunderstandings, misinterpretations and mistreatment. Paderborn 1885, p. 170.

- ^ Paola Ivanov: Pre-colonial history and expansion of the Avungara-Azande. R. Köppe, 2000, p. 78.

- ↑ Wolfgang Cremer: Pipes, hemp and tobacco in Black Africa: A historical representation. 2004, p. 180.

- ↑ Susan Arndt, Heiko Thierl, Ralf Walther: AfrikaBilder: Studies on racism in Germany. Unrast 2001, p. 369.

- ↑ Georg Schweinfurth: In the Heart of Africa , Chapter 12 The people of Niamniam, the "Wolverine".

- ↑ Lotte Burkhardt: Directory of eponymous plant names - Extended Edition. Part I and II. Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin , Freie Universität Berlin , Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-946292-26-5 doi: 10.3372 / epolist2018 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schweinfurth, Georg |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Schweinfurth, Georg August (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German Africa explorer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 29, 1836 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Riga , Livonia Governorate , Russian Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 19, 1925 |

| Place of death | Berlin |