Georg Melantrich from Aventine

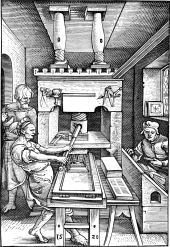

Georg Melantrich von Aventin ( Czech Jiří Melantrich z Aventina , originally Jiří Černý Rožďalovický ; * around 1511 in Rožďalovice , † November 19, 1580 in Prague ) was a Czech printer and publisher during the Renaissance .

He expanded his printing house into a company of European format. The basis of his business became the Bible , which he probably edited four or five times. He published a wide range of religious and edifying works for Catholic and Lutheran audiences, humanistic literature, and Latin poetry . His collaboration with the Italian doctor and botanist Pietro Andrea Mattioli was of international importance . His workshop also produced manuals and dictionaries, legal works, and entertainment literature.

Melantrich was a member of the Prague Old Town Council . In 1557 he was raised to the nobility. He was a humanistically educated Utraquist , influenced by the Lutheran faith and tolerant of Catholics.

From 1576 he worked with his son-in-law Daniel Adam z Veleslavína , who took over and continued the printing company after Melantrich's death.

Childhood and youth

The date of birth of Jiřík Černý, who later became Melantrich of Aventine, is unknown. The often given year 1511 is based on the historical calendar of Daniel Adam , according to which Melantrich was 69 years old. He came from a simple utraquist family. In 1534 he entered the arts faculty of Charles University in Prague as a bachelor's degree .

It is assumed that after obtaining his bachelor's degree he went to study in Wittenberg , where the German humanist and theologian Philipp Melanchthon taught at the time, but it has not been proven. During this time, Jiří Černý changed his last name to Melantrichos (Greek "Schwarzkopf"). The often-voiced assumption that Melantrich met Sigismund Gelenius , who had been employed in Johann Froben's printing works in Basel since 1524 , is not supported by the sources.

The historian Zikmund Winter writes that a certain Jiří Černý printed an edifying brochure in 1541 . It was his first and last work, because his printing company went bankrupt after it was published . Whether this Jiří Černý was identical with Melantrich is unproven. Melantrich is clearly documented in 1545 during the reign of Johann von Pernstein in Prostějov , Moravia , where he worked in Jan Günther's print shop on the book Doktora Urbana Rhegia rozmlouvání s Annou, manželkou svou (Doctor Urbanus Rhegius' conversation with his wife Anna) . Melantrich later published this book twice.

Beginnings in Prague

Melantrich worked in Prostějov until the end of 1546 or beginning of 1547. Then he went to Prague , which was experiencing an economic boom at the time. The Severin-Kamp printing company had been working in Prague since 1488. Among other things, two Bible editions emerged from it in 1529 and 1537. Only this one company survived the crisis in the 1520s. In 1544, however, ten printing works were again working in Prague and their number grew steadily.

Melantrich brought printing material with him from Moravia and in 1547 he published another work by Rhegios, the Czech translation of his catechism . However, the promising beginning of the workshop was interrupted by a printing ban that Ferdinand I issued in response to the first class uprising in Bohemia in 1547. Melantrich then entered the business of Bartoloměj Netolický, who as a moderate Catholic was not affected by the ban. Officially only an employee, Melantrich was obviously an equal partner in business terms. The work of the two printers can be clearly distinguished according to the letters and other typographical material used. Melantrich took part in the printing of the documents that Ferdinand I had compiled for the uprising and the religious work Testamentové a neb kšaftové dvanácti patriarchův ( Testaments of the twelve patriarchs ). He prepared intensively for the main project of the coming years, the new edition of the Czech Bible . It was later referred to as the Melantrich Bible or Melantriška .

The Bible, especially as a complete edition in the Czech language, was a lucrative commodity in Bohemia in the 16th century. Their edition greatly increased the printer's prestige. Melantrich was fully aware of this. That is why he is already listed as a partner of Netolický in the first edition from 1549. Although the Bible promised certain profit, the preparation and printing of such a large book were extremely time-consuming and took several years. Without large savings or a rich sponsor, the project could not be carried out, because there were still no opportunities to take out a loan for such a project. In addition to providing legal security, Netolický obviously also provided Melantrich with financial support. Undoubtedly at Melantrich's instigation, Netolický also secured the privilege to print and sell the Bible for a period of ten years. The translator and chancellor of Prague's old town Sixt von Ottersdorf subjected the Czech text of the Melantrich Bible to a linguistic test, and the typographical design of the book was carefully planned. The edition brought Melantrich a considerable profit and, together with other Bible editions, became the mainstay of his enterprise.

By 1552 Melantrich published another 17 titles. With the exception of the New Textament of 1551, however, they were rather of a smaller size.

independence

The years 1552–1560

In 1552 Melantrich took over the Netolický printing house and went into business for himself. As early as 1550, the Prague printers were gradually granted new privileges, initially limited to individual books. Obviously, the decisive factor was that Melantrich succeeded in buying the privilege for the Bible from Netolický. He relocated the printing company from Lesser Town to Prague's Old Town , where he had already bought a house in 1551 and acquired citizenship .

At that time he printed rather smaller titles, for example the bloodletting calendar , peasant practices , a prayer book, another Czech translation by Urbanus Rhegius, a book called Studnice života (Fountain of Life) or the chancellery manual Formy a notule čili Tytulář . He married in 1554, but his wife died a short time later. He married again the following year. Obviously, after starting his own business, he held back because he was busy buying and renovating the house. But he also made new business and social contacts. Melantrich had contact with the humanist and patron Jan Hodějovský z Hodějova and with other scholars from his circle, for example with the young Thaddaeus Hagecius . Contacts with the court of the Bohemian governor Ferdinand II of Tyrol were also important .

On December 7, 1556, the second edition of the Melantrich Bible appeared. He had been working on it since 1555 and was issuing a very large number of copies, as the privilege of selling it ended in 1559. The edition had a new title page and Melantrich used a new printer signet for the first time . Although it was re-set, it only differed from the previous edition in details.

Immediately after the Bible had finished printing, work on other titles began. Among them was, for example, the book of funeral sermons by the reformer Johann Spangenberg . The Latin poetry collections of Melantrich's humanistic friends are small in size and print run, but of high quality in typography. One of these collections contained verses in celebration of the wedding of Wilhelm von Rosenberg on February 28, 1557. It is probably no coincidence that this noblewoman later published the popular Lutheran book of edification Jesus Syrach, jinak Ecclesisticus with the subtitle zrcadlo pobožnosti, ctnosti, kázně i počestnosti (mirror of piety, discipline, virtue and respectability), which Luther's friend Caspar Huberinus wrote and which Tomas Reschl, Catholic priest in Königgrätz , had translated into Czech. The book was first published in 1557 and then a few more times.

In mid-August 1557 Melantrich was honored with a coat of arms and the title of nobility from Aventine . The name refers to the Roman Aventine , where the first public library was located. On June 20, 1558 he became councilor of Prague's Old Town . With an interruption in the years 1560–1565, in which Melantrich's main entrepreneurial activity falls, he participated in the city administration as councilor until 1579.

During this time Melantrich published rather smaller prints. In 1558 he printed the New Testament in small format, a year later a similar octave edition of the illustrated Gospels and Epistles . Every year he published the bloodletting calendar and the peasant practice and also printed the files of the state parliament .

The years 1561–1564

In 1561, in addition to smaller collections of poetry, bloodletting calendars, peasant rules, meeting files, a new edition of Jesus Syrach and a third edition of the Bible, the book Epistolarum Medicinalium libri quinque ( doctors' letters in five books ) was printed, the letters of the Italian doctor, naturalist and botanist Pietro Andrea Mattioli to important patients. Mattioli lived in Prague as Ferdinand von Tirol's personal physician from 1554 . The doctor's letters, with the imprint of which new medical discoveries were published at that time, were a prestige project and Melantrich had a new signet made for this occasion, proudly bearing the Latin motto nec igne nec ferro (neither through fire nor through iron (I go under)) announced. The book was sold all over Europe and granted stately privileges for this market.

Immediately thereafter, Melantrich began work on another, now much better known work by Matthioli - his herbarium . The Czech edition was ready in 1562. It was the first Czech edition of the book, which was already known across Europe at the time. Compared to previous editions, the book was expanded and revised by the author. Melantrich received the royal privilege for the edition as early as 1554.

The initiator of the edition was probably Ferdinand von Tirol, who verifiably supported the preparation and printing. All those affected, including Melantrich, were involved in the financing. Mainly because of the more than 200 large and lavishly executed woodcuts , the project was even more demanding than Melantrich's first Bible edition.

Thaddaeus Hagecius translated the herbarium into Czech. The German version, translated by the doctor Georg Handsch , appeared in 1563. The almost simultaneous edition of the Czech and German versions covered the entire book market in Central Europe. The Czech edition was sold in the countries of the Bohemian Crown and in Poland , the German in Germany, Austria and other countries with a German-speaking population, not excluding Bohemia.

At that time there was no well-developed book trade . The books were sold unbound directly in the offices and at fairs , including at the Frankfurt Book Fair , which Melantrich attended. A large number of the books were also sold by bookbinders .

Simultaneously with the herbarium, Melantrich published three Latin textbooks, including Melanchton's Latin grammar, as well as a number of smaller publications. In 1562 Melantrich edited at least 19 books, the highest annual output of his print shop ever.

In 1563, in addition to the usual bloodletting calendar and the peasant rules, Melantrich published other small collections of poetry, including a collection by Bohuslaus Lobkowicz von Hassenstein , and the edifying booklet O nekřesťanském a hrozném lání, rouhání, Bohu zlořečení (On the terrible unchristian, Cursing and blasphemy) and above all a book by the Dutch scholar Erasmus von Rotterdam with the long title: Kniha Erasma Rotterdamského, v kteréž se jednomu každému křesťanskému člověku naučení dává, jak by se k smrti hotoviti in demasěl ( teaching every Christian how to prepare for death). The book contains woodcuts by Hans Holbein the Younger . The woodcuts were made from scratch in Prague. This made it possible to change some satirical, anti-Catholic scenes. The text was translated by the chief judge Johann Popel von Lobkowitz , who had been the Czech censor since 1547 . The book was therefore published without any difficulties and even experienced a new edition.

The most important work of Melantrichs in 1564 was the book Práva a zřízení zemská království Českého (The rights and the national order of the Kingdom of Bohemia) by Wolf z Vřesovic, which describes the legal and political constitution of the then Bohemia. The edition also contains a full-page illustration of a session of the regional court.

The years 1564–1570

After 1564 there was a certain break in Melantrich's production. Only more popular titles are published, in some cases new editions of older works, but only a few really large and weighty projects, as was the case with the herbarium. There are several possible reasons. Melantrich was already 53 years old, he devoted himself again intensively to work in the city council and also had the large and representative Renaissance house U dvou velbloudů (near the two camels) in Kunešov in today's Melantrichova ulice from 1563-67 , which is still one of the Main streets of Prague's Old Town, bought and completely renovated. This house, later also called Melantrich House, was demolished at the end of the 19th century. Melantrich lived here with the whole family, and the printing shop was also located here. Another reason for Melantrich's reduced business activity was that Archduke Ferdinand moved away from Prague and moved to Ambras Castle in Tyrol . Up until the time of Rudolf II, Prague had lost the character of a royal seat . Important personalities, humanists of European format and humanistically oriented Czechs, for example Thaddaeus Hagecius, were now far more attracted to the court of Maximilian II in Vienna than to Prague. In addition, Jan Hodějovský z Hodějova died in 1566, so that Melantrich's circle of humanistically oriented friends and employees, but also patrons and customers, had disintegrated.

In 1564 Melantrich asked for a new privilege to print Bibles. He not only prepared a new edition, but also endeavored to avert competitors. In addition, he defended himself indirectly against illegal book imports, which mainly brought the so-called Nuremberg Bible into the country. This was another Czech translation of the Bible published in 1540 by Anton Koberger .

Aside from smaller collections of poetry, the occasional works of this period include the prints on the occasion of the death of Emperor Ferdinand I. Vincenc Makovský z Makova, administrator of the school at the Church of St. Nicholas on the Lesser Quarter, wrote the Elegii na smrt císaře Ferdinanda ( elegies on the death of Emperor Ferdinand) in 1565 , Archbishop Antonín Brus z Mohelnice gave his funeral oration in print and Heinrich Scribonius, Provost of the Metropolitan Chapter at St. Vitus , expressed his grief in writing. In 1566 the humanist Johann Balbin wrote the work Querela Iusticie čili Nářek spravedlnosti , in which it is stated that after the death of the emperor "justice fled to heaven and is absent on earth."

In 1565 Melantrich also published the sermons of Girolamo Savonarola under the title Sedmero krásné a potěšitelné kázání (Seven beautiful and comforting sermons). The book was obviously selling well, as Melantrich published two more reprints in the following years.

An entertainment book entitled Kronika o Herkulesovi (Chronicle of Hercules ) by the Prague dean and mathematician Sigmund Antoch von Helfenberg also found good sales . Melantrich had the popular folk books popular at that time in his program, as evidenced by book lists and the few surviving copies. In addition to the surviving wills of the twelve patriarchs and the richly illustrated allegorical mirror Theriobulia by Johannes Dubravius , according to a list from 1586, there were: Alexandreis , Apollonius, Brigida, Bruncvík , Eulenspiegel , Fortunatus , Frantova práva (old Czech rascals guild ), Jovian , Salman and Morolf , Meluzína , Pyramus and Thisbe and the popular Kronika sedmi mudrců ( The Seven Wise Masters ).

A notable edition from 1567 was called Knížka v českém a německém jazyku složená, kterak by Čech německy a Němec česky… učiti se měl (little book in Czech and German on how the Czechs should learn German and the Germans learn Czech). The popular conversation manual of Andreas von Glatau was reprinted up to the 17th century. In 1568 Melantrich published the Latin comedies of Publius Terentius Afer , among other things . All of these books sold very well and served as a welcome replacement for the large edition projects of the first half of the decade.

After 1570

In 1570 there was finally a new edition of the Bible. The work had a new index and register . Most importantly, it received a completely new set of woodcuts created especially for this edition by top artists. It is therefore no wonder that the typographic and artistic quality of the edition makes it one of the best Czech prints ever.

The title page has also been redesigned and features the only known image of Melantrich. The more than one hundred woodcuts represented a completely new understanding of illustration , which clearly stands out from the publications common at the time and ties in with contemporary Italian painting and graphics . The Bible was dedicated to Emperor Maximilian II. After his death in 1576, Melantrich apparently inserted a new title page with a dedication to Emperor Rudolf II in the remaining unsold edition. Somewhat surprisingly, there were censors' comments on the edition of 1570, although the text did not differ from previous editions. This obviously shows the tension and religious polarization that can also be felt elsewhere, which culminated in the second Bohemian uprising in 1618 .

A number of Melantrich's younger employees, who were involved in editions of school books and other publications at that time , were later connected to the struggle for the Confessio Bohemica . Their supporters belonged to the ranks of the Protestant opposition. Among other things, it was the Prague rector Petrus Codicillus von Tulechov who wrote the bloodletting calendar and peasant rules and prepared the new Latin-Czech-German dictionary , which was published in 1575 with great success. Another was the theologian, Hebrew and preacher Paul Pressius , who prepared a textbook on grammar for Melantrich.

Although Melantrich was closest to Lutheran in the field of religious literature (Rhegius, Mathesius), he also published works that were accepted on all sides (Jesus Syrach, the sermons of Erasmus of Rotterdam, Thomas von Kempen ) also outspokenly Catholic works, such as the already mentioned sermons by Savonarola or the postil of Johann Ferro printed in 1575 at the expense of Archbishop Antonín Brus and Wilhelm von Rosenberg . This two-volume publication stands out again for its typographical quality and it does not give the impression that Melantrich printed it out of compulsion, as was stated in older literature in his "defense". It is much more likely that Melantrich wanted to offer the widest possible range. Ferros Postille is adorned with first-class woodcuts and set with the special Melantrich- Schwabacher , which contained a complete set of diacritics , so that it was not necessary to work with digraphs as in older prints . Some of the printing blocks that Melantrich used for Ferros Postille were already used in 1564 for the illegal issue of Jan Hus's postil. The older assumption that the sticks would prove the origin of Hussen's book from Melantrich's workshop is unlikely, however. Melantrich had probably bought the sticks second-hand in Nuremberg, where Hus's postil was probably printed in 1564.

The Confessio Bohemica, in which a number of Melantrich's friends participated, he could not print even out of consideration for the emperor. On the contrary, in 1575 he published a congratulatory poem by the court archivist Paul Seller on the occasion of Rudolf's coronation.

Collaboration with Daniel Adam z Veleslavína

In 1576 Melantrich engaged his eldest, then nineteen-year-old daughter Anna to the thirty-year-old Prague professor Daniel Adam z Veleslavína . No doubt he did it for practical reasons, as he had to hand over the prosperous company to a capable successor. The wedding took place on November 27, 1576, and on this occasion a small anthology with Latin verses was published. Daniel Adam, who had been using the title “z Veleslavína” since 1578, began to act as Melantrich's partner and run the printing company immediately after the wedding. This brought new dynamism to the book edition, but also certain operational problems. In 1577, for example, the archbishop threatened to close the printing works because they mistakenly or deliberately failed to submit the Bible edition to the censors. The Veleslavín, close to Calvinism and the Brethren , was obviously not ready for fine maneuvering and compromises, as Melantrich had done up to then.

In 1577 Cicero's Latin letters and the extensive Latin thesaurus of Basil Faber came out. In 1578 the highly regarded historical Veleslavín calendar was published. Another well-known work was printed in 1579: Práva městská Království českého (The City Rights of the Kingdom of Bohemia) by the lawyer Paul Christian von Koldin .

The books mentioned above were the joint work of the two printers. Melantrich independently published the songs of Šimon Lomnický z Budče and the dialogues of the Swiss humanist and Calvin opponent Sebastian Castellio . Melantrich's last book was the Massopust (Carnival), a moral book by the utraquist pastor Vavřinec Leandr Rváčovský, which was written in a coarse language.

On Tuesday, November 15, 1580, Melantrich dictated his will . He died on Saturday, November 19th. He was buried in the Bethlehem Chapel. The strained relationship with Veleslavín is shown by the fact that Melantrich left him with absolutely nothing. Melantrich's son Jiří, who was still underage at the time, inherited the business and the father also gave the other children generous consideration. Veleslavín ran the business until 1584, when Jiří, who had come of age, took over. However, this was heavily indebted. After his untimely death in 1586, Daniel Adam took over the printing business again as the main believer . He continued his edition policy, which had already been established in 1576 and was in some ways linked to Melantrich. Like Melantrich, Daniel Adam was the most important Bohemian printer of his time. While Melantrich was more concerned with compromise and tolerance, Veleslavín acted much more purposefully. In this, too, both reflected the time in which they lived.

Melantrich's legacy

Typographer

We know practically nothing about Melantrich's training, but it is very likely that he actually got to know the operation of a large print shop , such as Froben's office in Basel. This suggests his thorough knowledge of typography and the printing trade , as well as experience with publishing , its organization and economy.

The quality of Melantrich's publications consists not only in the good typesetting and careful large woodcuts , but also in the typographical arrangement of the typesetting, the appropriate and sensitive use of initials and other decorative elements, in the composition of individual pages, and especially in the design of the title pages recognizable, and also in the ability to combine and select different fonts . All of this betrays an obvious artistic talent. This ability can be seen most clearly in the small prints of Latin poetry, because these works did not have to attract the buyers' attention with a large amount of text flowery touting the book on offer.

Entrepreneur

From 1547 to 1580 Melantrich published at least 223 book titles and smaller prints. The number was probably higher because the small occasional prints and the entertainment literature in particular have often not survived and there are no other testimonies to them either. Of the known publications, 111 were Czech , 75 Latin , 3 German , one Italian and 33 multilingual (textbooks and dictionaries). The thematic range of Melantrich's company was also large and demonstrates the ability to recognize and cover a gap in the market at the right time and skillfully master unexpected twists and turns and difficulties. Melantrich's success was also due to the fact that he was able to win capable friends, employees and patrons. The operational sequence was organized in such a way that the work on extensive representative projects alternated with the printing of smaller casual or entertainment books. The editions of his prints were a few thousand, a very high number at the time. Melantrich supplemented it with frequent reprints of already sold out titles. He also played the de facto role of the court and country printer in the Kingdom of Bohemia . The surviving texts of a personal character, especially Melantrich's testament or the foreword to the Bible, present him as a pious, sincere believing man.

Czech ore typographer

During the time of the national rebirth , especially in their shooting phase, Melantrich, like Jan Ámos Komenský or Jan Hus , became extremely popular. With his entrepreneurial success, the humanistic foresight, with the fact that he had dedicated his life to the edition of Czech books, with many assumed and actual personal characteristics, he corresponded exactly to the ideals of the emancipating Czech society. He was therefore honored with the title of Czech archetype , which can be found, for example, on the plaque in the town hall of his native Rožďalovice .

From 1910, the Melantrich publishing house used the name of the Renaissance printer. This publisher was almost as important during the First Republic as Melantrich was in Renaissance Bohemia.

literature

- Jiří Pešek: Jiří Melantrich z Aventýna - Příběh pražského arcitiskaře , Slovo k historii 32, Melantrich, Prague 1991.

- Zikmund Winter: Řemeslnictvo a živnosti 16. věku v Čechách: 1526-1620 , Česká akademie císaře Františka Josefa pro vědy, slovesnost a umění, Prague 1909, pp. 265–272 ( online ).

Web links

Remarks

- Jump up ↑ Jiří Pešek: Jiří Melantrich z Aventýna - Příběh pražského arcitiskaře , Slovo k historii 32, Melantrich, Prague 1991, pp. 1-4.

- ↑ Karel Herain: Jiří Melantrich z Aventina , Umění V., 1932, p. 129.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 5.

- ↑ The collection was published in 1548 under the title Akta těch všech věcí, které jsou se mezi nejjasnějším knížetem a pánem panem Ferdinandem I. a některými osobami ze stavův panského, rytířského a městského kresálovstvi. léta 1547 zběhly , cf. the advertisement of the 1880 reprint here .

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 6–9.

- ↑ a b Jiří Pešek, p. 10.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 10-12.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 15-16.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 16.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 17-19.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 20.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 21.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 22-24.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 24.

- ↑ a b Jiří Pešek, p. 25.

- ↑ Dobroslav Líbal, Jan Muk: Staré město pražské - architektonický a urbanistický vývoj , Prague 1996, pp 248-250.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 25-27.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 27.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 30.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 30–32.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 32.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 34.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 35.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 36.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 37.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 37–39.

- ↑ a b Jiří Pešek, pp. 2–3, 14–15, 37.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Jiří Pešek, p. 1.

- ↑ Vojtěch Pejlek: Melantrich 1898-1998 , Melantrich, Praha 1998, p. 121.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Melantrich from Aventine, Georg |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Melantrich z Aventina, Jiří |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Bohemian printer and publisher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1511 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Rožďalovice |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 19, 1580 |

| Place of death | Prague |