Hestercombe Gardens

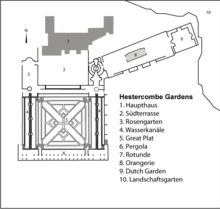

Hestercombe Gardens is part of Hestercombe House in the county of Somerset in southwest England . The entire garden area comprises three individual gardens from different style periods. The Edwardian garden was of supraregional importance from the beginning of the 20th century, the first joint work by the gardener and artist Gertrude Jekyll and the architect Edwin Lutyens . Hestercombe Gardens is now one of the most important listed gardens of the 20th century and is owned by the Hestercombe Garden Trust.

location

Hestercombe Gardens is located near the English village of Cheddon Fitzpaine and north of the town of Taunton in Taunton Deane in the English county of Somerset . The house and garden are surrounded by the Quantock Hills . The terrain slopes slightly towards the south and offers a sweeping view of the Taunton Valley and the Blackdown Hills.

history

In the 16th century, a country house for the English family of Richard Warre was first built on what is now Hestercombe Gardens. His son was a son-in-law of the influential English lord judge John Popham. In the 18th century the country house and the surrounding lands were owned by Coplestone Warre Bampfylde (1720–1791), a friend of Henry Hoares . The country house was enlarged and a Georgian landscaped garden was laid out under Bampflyde's guidance . In 1873 the property was owned by Edward Portman, 1st Viscount Portman . This also caused major changes to the house and garden, which were carried out between 1873 and 1878. In doing so, the main building got its present shape in a predominantly Victorian style . EWB Portman, eldest son of the 2nd Viscount Portman, received the property as a wedding present from his grandfather. He commissioned Gertrud Jekyll and Edward Lutyens with the structural and horticultural redesign of the garden in front of the house and to the side of it. This was carried out from 1904 to 1909.

The house and gardens were owned by the Portman family until 1944. In World War II, which used British Army the building. Here was part of the headquarters of the 8th Corps , whose mission was the defense of Somerset, Devon , Cornwall and Bristol . As part of the preparation for the invasion of Normandy , the 398th General Service Engineer Regiment was also stationed here and an American hospital was built after D-Day . In 1951 the house and land became the property of Somerset County Council. This used the building for administrative purposes and - to this day - as the headquarters of the Somerset Fire and Rescue Service. In the meantime, the entire complex has become the property of the Hestercombe Garden Trust , of which Somerset County Council is now the tenant.

In the 1970s the house and gardens were extensively restored, both of which were in a ruinous state at that time. Due to their complexity, the restoration of the perennial beds could not be carried out according to Jekyll's planting plans, but was carried out in a simplified form and in Jekyll's style.

In 1992 the landscape garden of the 18th century, which had meanwhile been forgotten, was rediscovered, exposed and restored according to original illustrations. At the beginning of the 21st century, part of the area was also designated as a “Biological Site of Special Scientific Interest”, as a rare species of bat ( lesser horseshoe bat , Rhinolophus hipposideros ) lives here.

The Georgian Landscape Garden

The English landscape garden from the 2nd half of the 18th century is the oldest garden in Hestercombe Gardens . It was laid out between 1750 and 1786 by the then owner of the property, Coplestone Warre Bampfylde. The Georgian landscape park, which is just over 16 hectares in size, is located in a valley north of the manor house. The landscape garden designed by Bampfylde himself was inspired by the then very modern “ Arcadian style ”. Plants were rather less important as ornamental objects in these gardens designed in this way and did not play a major role as an independent design element. Rather, trees and bushes should create moods and views in interaction with the surrounding landscape. Components of the landscape garden were a cascade waterfall, seating in areas that stand out in terms of landscape and perspective, a small temple and artificial ruins of a temple in the Greek style and a mausoleum .

The landscape garden was later neglected and was completely forgotten by the end of the 19th century at the latest. In 1992 it was rediscovered and exposed. The relatively high costs of restoration were mainly due to the restoration of the buildings. Funds from the National Lottery were also used for this purpose. The watercolors of his landscape garden made and preserved by Bampfylde, who was a painter, provided valuable information on how to restore them to the original.

As a landscape garden of the 18th century, however, the complex was rather insignificant. In no way can it be compared with landscape gardens that were created at the same time, such as the nearby Stourhead .

The Victorian garden

The Victorian Garden (called the Victorian Terrace or South Terrace) is in front of the manor house and above the Great Plat . Probably the first Viscount Portman had this garden laid out by the architect Henry Hall between 1873 and 1878 when he commissioned major changes to the house. The terrace looks out over the formal garden into the Taunton Valley. The Victorian Garden is framed by a rose garden (west) and the rotunda (east).

Lutyens and Jekyll added the so-called Gray walk to the south terrace . This is a densely planted to ignore passing over the entire length of the building herbaceous border . Scented perennials were used here in blue-silver-white colors such as lavender , rosemary , catnip , or baby's breath .

The Edwardian formal garden

Edward Lutyens was commissioned in 1903 to design a formal garden for Hestercombe House. Lutyens' first task in creating the design concept for the approximately 1.5 hectare site was to take into account the house itself. At the time, it was a Victorian building that was considered extremely unattractive and not very elegant. In front of the front of the house, the terrain sloped gently to the south and gave an unobstructed view of the Taunton Valley. That is why he planned the center of the garden to the south and thus in the front of the front building. The visitor's attention should be drawn away from the house to the center of the facility. In addition, the view fell into the far- reaching landscape of Eastern Devon over the Tornton Dean to the Blackdown Hills. Other parts of the new formal layout also extended diagonally to the east of the house.

Lutyens worked on the formal garden for a total of five years. During this time he was responsible for the overall planning as an architect and was also responsible for the planning of architectural details such as the use of building materials or the design of the water systems, the orangery or the decorative and useful elements of the garden. As in previous joint projects, his colleague on horticultural issues was Gertrude Jekyll. She drafted the planting plans for the borders and beds and adjusted the plants to the existing structural conditions.

The Great Plat - Center of the Edwardian Gardens

The center of the central part of the garden is The Great Plat , a ground floor made up of lawns and flower beds. Lutyens used the stylistic devices of gardens from the Tudor period and Italian Renaissance gardens . It is a so-called sunken garden , i.e. a large, lowered ground floor with lawn and plants and a pergola at the southern end.

The parterre garden is below the house and is laid out in a square. The link to the higher house is a wall made of rubble stones on the north side . Direct access to the house with its horizontally running double borders and the lawn path in between was not included in the planning.

The relatively large area of the Great Plat was geometrically structured and loosened up by Lutyens primarily by means of a diagonal cross of paths. The crossroads consists of stone bands running in the grass, which are bordered with slate and delimit the four wide grass paths. At the end of each path a quarter-circle staircase was created. The ground floor is bordered on three sides by massive quarry stone walls made of broken slate plates, which are also planted.

The area of the Great Plat is divided into four triangular beds, the edges of which are made of natural stone slabs and strips of planted Bergenia cordifolia . Here Lutyens was inspired by the concept of the parterre de pièces coupées pour des fleurs and the parterre à l'angloise . This means that the flower borders do not lie between gravel , but between lawn and pavement and, contrary to the concepts of Renaissance and Baroque gardens, are bordered with natural borders made of plant bands. Common elements in the planning of the individual beds in Jekyll are the double borders and the planting of the retaining walls.

Lutyens built a low wall with a pergola over the entire length of the south side of the Great Plat (72 m). This serves both as the end of the terrace to the south, but at the same time as a transparent link between the garden and the landscape on the other due to its construction. At the same time, it also connects the two water basins on the terraces on the side of the middle ground floor. In the pergola, round and angular columns alternate, which are piled up from rubble stones of regional origin. The pergola is lush with various climbing plants such as climbing roses , clematis , wisteria , honeysuckle or grapevines .

Jekyll's planting plans show that she set different vertical accents in the plantings to counteract the depth of the sunken parterre. For example, solitary plantings with tall grass perennials brought the Great Plat closer to the three higher garden sides.

Side terraces

On either side of the Great Plat are two higher garden terraces. They frame the central garden area on both sides and connect the building to the north with the pergola at the southern end of the garden. Over the entire length of the side terraces of 43 m, two small walled water channels run from north to south , which are surrounded by lawns and plant beds. The canals are walled with a total of three circular loops at regular intervals. The water channels are fed by two round grotto-shaped niche wells at the northern ends of the terrace. Both water channels end in rectangular water lily ponds just before the transverse pergola and are lushly planted with various aquatic and marsh plants. For example, irises , calla , frog spoons or arrow herbs were used .

While the western side terrace ends below the Victorian garden in front of the house, the eastern side terrace ends below the rotunda, which connects the garden areas below the house with the orangery and the Dutch Garden to the east of the main house .

Gertrud Jekyll was inspired by the pattern of old handicrafts for the central garden element, the partly circularly entwined water channels. In addition, there are clear Italian and Moorish-Islamic influences.

Eastern part of the garden

The garden section, which is closed off to the east, essentially consists of three parts: the rotunda, a rectangular orangery in the middle and the so-called Dutch Garden at the end. The entire complex follows the main house, which recedes on the eastern side, and thus has a slightly northeastern orientation.

The rotunda is the connecting piece on the one hand to the east-lying side terrace and on the other hand borders directly on the victorian terrace , the Victorian garden on the south terrace in front of the main front of the house. The rotunda is a circular courtyard with a central circular water basin. The courtyard is surrounded by head-high walls made of rubble stones, in which niches are embedded. The adjoining orangery was intended to serve as a private retreat for the family. Lutyens designed it in the style of Christopher Wren and surrounded it with geometric lawn panels. The Dutch Garden is square and has four polygonal main perennial beds as well as numerous other circular, square or polygonal plant beds. Decorative elements designed by Lutyens himself, such as jewelry buckets or vases, enhance them.

The perennial beds of the Dutch Gardens are mostly planted with white and silver colored plants. Large white flowering Yucca gloriosa as groups used vertical elements alternate with colored purple flowered dwarf lavender (Lavandula) , catnip (Nepeta) or silver-colored Stachys (Stachys) , Santolina from or rosemary. The Chinese roses or fuchsias (Fuchsia magellanica) that are also used are contrasted in color .

Planting plans and concepts

The planting plans designed by Gertrud Jekyll for the formal garden of Hestercombe Gardens were extremely complex and included a multitude of precisely coordinated perennial species and varieties as well as summer floriferous plants. To do this, she used and mixed native cultivated plants with simple wild herbs and exotic plants from other continents. She often combined flowering plants with leafy plants in order to emphasize the color effect of the flowers even more with suitable, color-contrasting leaf colors.

The planting in Hestercombe Gardens had both a strengthening and a moderating effect on the architecture. Gertrud Jekyll used the strict order and regularity of the architectural elements as a framework for her “plant pictures”, her perennial and floral borders.

As a trained painter, she brought her own impressionistic influences and ways of seeing into the color composition of the plants in the plant arrangements. It is also known that Jekyll liked to be inspired by the well-known English landscape painter William Turner , whose work she copied during her student years at the National Gallery in London when dealing with colors and shades of color .

However, the planting plans designed for the formal garden could not be implemented in the long term - the horticultural effort had been too great. Even when the formal garden was restored from 1973 onwards, the perennial and summer flowerbeds were no longer exactly replanted, but only reconstructed in a simplified manner based on Jekyll's original plans.

Garden architecture

Edward Lutyens was solely responsible for the construction planning , the architectural elements of the formal garden and the selection and use of the necessary building elements and materials. Due to the fact that the mansion was not included, he planned the garden to move away from the house. The view of the visitor should therefore lead away from the rather inconspicuous house. To this end, Lutyen included the natural surroundings of Hestercombe House and, above all, the panorama of the south-west English landscape. The visitor should experience the garden as a diverse space.

The result was a formal garden in which Lutyens was inspired by stylistic garden elements from different eras. The concept of a square, geometrically structured base with laterally delimiting and higher terraces was already used in the 16th and 17th centuries, for example. In today's view of the garden, the elevated Dutch Garden is interpreted as a reminiscence of the Dutch influence on English Tudor gardens. The orangery, which is also to the side of the main ground floor, is also historicizing in its architectural style and deliberately copies the architectural style of Christopher Wren. Lutyens also attached particular importance to the line of sight in the individual garden areas, which can already be found in Italian models of the Renaissance period such as the Villa Lante . The existing water basins and channels are reminiscent of the garden concepts of the typical architectural garden of the 19th century.

Inspired in this way and further developing his own ideas, Lutyens preferred geometric structures that often alternated when laying out the garden areas. In Hestercombe Gardens, for example, there are numerous level changes with staircases and stairs, orientation axes, pergolas, lookout points (so-called "vistas") as well as water basins and water channels. Lutyens was careful to ensure that the architecture served the garden itself and did not dominate it. Connections between stone and plant were deliberately planned everywhere, for example in the vegetation on the large terrace retaining walls on the side ground floor.

Lutyens was known for paying great attention to the materials used in his architectural planning. He liked to use regional stone types for this, including in the formal garden of Hestercombe Gardens. The so-called "Ham-Hill stone", a warm, sand-colored type of sandstone , was used here to a large extent . This sandstone was mainly used to build niches, balustrades , banisters and the orangery as a large building. Locally occurring slate (local lias , called morte ) was used to a large extent, especially for walls, stone slabs, step systems or water basins. Lutyens took up the principle of the dry stone wall layered out of slate stones, which is a common feature of the region in south-west England. Walls of this kind can be planted over a large area without any major inconvenience, a circumstance that Jekyll used to further expand the connection between plants and architecture, which can be found again and again. The large pergola was also made of slate. The alternating square and round columns were layered from evenly thin natural stones. As a further design element, the building material used was processed and used in different ways, such as quarry stone, finely cut or ground.

Lutyens created a certain rusticity through the use of local stone types in alternating shapes and colors. This was not typical of gardens of the early Edwardian period, but it clearly shows the influence of the Arts and Crafts movement on it.

Collaboration between Gertrude Jekyll and Sir Edwin Lutyens

The productive collaboration between gardener (as she called herself) Gertrud Jekyll and the much younger architect Edward Lutyens began in 1896 and lasted until 1912. During this time, they designed around 100 gardens together. When they worked together, Lutyens designed the building, designed the spatial arrangement of the garden and planned the structural details. Jekyll was responsible for the planting plans and finally checked the overall appearance of the architecture and the plant.

The synthesis of formalism and architecture with naturalism and nature by means of the finely tuned selection of plants was typical of this collaboration . Lutyens provided the formal backbone of the complex and ensured that the house and open space were harmoniously interlinked. Jekyll supplemented this with border compositions coordinated in color and texture. There is agreement among experts that Jekyll's work has given the garden architectural element of the perennial borders a new reputation thanks to the combination of horticultural knowledge and artistic standards. With their respective skills and their combination, Jekyll and Lutyens developed gardens, the typical style of which was the division of the system into departments and rooms, the conception of viewing axes and the existence of different levels. Ornate stairs and paving, the frequent use of material from the respective region, the element of water and the planting that always corresponded to the respective conditions were also typical.

The formal garden at Hestercombe Gardens was the first major Jekyll and Lutyens garden project to emerge in this style. As part of their collaboration, both quickly gained a certain degree of notoriety in the English aristocratic circles, whereby Lutyens, who was previously unknown as an architect, benefited from Jekyll's good contacts. Around 1900 the statement "A Lutyens House with a Jekyll garden" was the epitome of the finest English lifestyle. The well-known English garden writer Penelope Hobhouse writes:

“The collaboration between the architect Edwin Lutyens and the gardener Gertrude Jekyll became the epitome of good taste and perfection for a generation that stood on the brink of the abyss that threatened the First World War. Architecture and planting strategy jointly created aesthetic and horticultural works, few of which have been preserved in their original state, but whose influence continues to have an effect in countless gardens. "

Assessment of Hestercombe Gardens in garden architecture and history

Leading garden architects and historians see the formal garden of Hestercombe Gardens as an outstanding example and masterpiece of the longstanding collaboration between Gertrud Jekyll and Edward Lutyens. The combination of formally designed systems as a “structural principle” with lush, non-formal planting as a typical “decorative principle” reached its artistic climax here. Hestercombe Gardens is also an example of "... that the architect can very well be in harmony with nature, that a formal garden can be part of the landscape."

At the same time, Hestercombe Gardens is an important contemporary manifestation of the Arts and Crafts movement, which was becoming popular at the time . Both Lutyens and Jekyll sympathized in many ways with this social as well as artistic trend. Important principles of movement such as closeness to nature and solid craftsmanship or the fairness of materials in the selection of construction materials were consistently implemented here. This is also an assessment of Hestercombe Gardens: "The attraction of Hestercombe lies in the subtle connection of the different levels, the changing viewpoints and, above all, in the harmonious selection of plants and building materials."

Hestercombe Gardens is an important milestone in the development of garden art in England and is logically one of the most important listed gardens of the 20th century. It shows the move away from the Victorian representative garden with its carpet beds and historicizing elements and the extensive English landscape garden towards the architectural garden . Aspects of natural plant growth became more important again. Ultimately, Hestercombe Gardens also shaped the typical image of a lush English country house garden, which in this form is typical of rural England, for many garden lovers.

literature

- Ursula Buchan, Andrew Lawson: English Garden Art. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-421-03663-6 .

- Reiner Herling: Classical English Gardens of the 20th Century. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8001-6541-4 .

- Richard Bisgrove: The Gardens of Gertrude Jekyll. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8001-6561-9 .

- Mark Laird, Hugh Palmer: The Formal Garden. Architectural landscape art from five centuries. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-421-03056-1 .

- Ehrenfried Kluckert, Rolf Toman: Garden art in Europe. From antiquity to the present. Ullmann, Potsdam 2013, ISBN 978-3-8480-0351-8 .

- Penelope Hobhouse : The Garden. Eine Kulturgeschichte Dorling Kindersley, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-8310-0481-1 .

- Günter Mader: History of garden art. Forays through four millennia. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-8001-4868-4 .

- Günter Mader, Laila Neubert-Mader: British garden art. DVA, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-421-03722-0 .

- Geoffrey Jellicoe , Susan Jellicoe, Patrick Goode, Michael Lancaster: The Oxford Companion to Gardens. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 0-19-286138-7 .

- Ira Diana Mazzoni : 50 Classics Gardens & Parks. Garden art from antiquity to today. Gerstenberg Verlag, Hildesheim 2008, ISBN 3-8369-2543-5 .

- Patrick Taylor: 100 English Gardens. The finest grounds in the English Heritage Parks and Gardens Register. Falken Verlag, Niedernhausen / Ts. 1996, ISBN 3-8068-4885-8 .

Web links

- hestercombe.com - Official website of the garden (English)

- Hestercombe Gardens - Parks & Gardens UK ( Memento of May 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- Hestercombe House Gardens - European Garden Network (EGHN)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Günter Mader: History of garden art. Forays through four millennia. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-8001-4868-4 ; P. 177.

- ↑ Reiner Herling: Classical English Gardens of the 20th Century. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8001-6541-4 ; P. 23.

- ↑ Reiner Herling: Classical English Gardens of the 20th Century. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8001-6541-4 ; P. 32.

- ↑ a b c d Reiner Herling: Classical English gardens of the 20th century. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8001-6541-4 , p. 25.

- ↑ a b Ehrenfried Kuckert, Rolf Toman: garden art in Europe. From antiquity to the present. Ullmann / Tandem, Königswinter 2007, ISBN 3-8331-3500-X , p. 479.

- ↑ Mark Laird, Hugh Palmer: The Formal Garden. Architectural landscape art from five centuries. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-421-03056-1 , p. 204.

- ↑ Ira Diana Mazzoni: 50 Classics Gardens & Parks. Garden art from antiquity to today. Gerstenberg Verlag, Hildesheim 2008, ISBN 3-8369-2543-5 , p. 224.

- ↑ Mark Laird, Hugh Palmer: The Formal Garden. Architectural landscape art from five centuries. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-421-03056-1 , p. 205.

- ↑ Patrick Taylor: 100 English Gardens. The finest grounds in the English Heritage Parks and Gardens Register. Falken Verlag, Niedernhausen / Ts. 1996, ISBN 3-8068-4885-8 ; P. 24.

- ^ A b Günter Mader: History of garden art. Forays through four millennia. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-8001-4868-4 , p. 175.

- ↑ Penelope Hobhouse: The Garden. Eine Kulturgeschichte Dorling Kindersley, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-8310-0481-1 ; P. 409.

- ↑ Reiner Herling: Classical English Gardens of the 20th Century. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-8001-6541-4 ; P. 23 ff.

- ↑ a b Penelope Hobhouse: The garden. Eine Kulturgeschichte Dorling Kindersley, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-8310-0481-1 ; P. 406.

- ^ A b Ira Diana Mazzoni: 50 Classics Gardens & Parks. Garden art from antiquity to today. Gerstenberg Verlag, Hildesheim 2008, ISBN 3-8369-2543-5 ; P. 222.

- ↑ Ursula Buchan, Andrew Lawson: English garden art. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-421-03663-6 ; P. 96.

- ↑ Representing: Ira Diana Mazzoni: 50 classic gardens & parks. Garden art from antiquity to today. Gerstenberg Verlag, Hildesheim 2008, ISBN 3-8369-2543-5 ; P. 223.

- ↑ Mark Laird, Hugh Palmer: The Formal Garden. Architectural landscape art from five centuries. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-421-03056-1 ; P. 176.

- ↑ Avray Tipping, quoted in Mark Laird, Hugh Palmer

- ↑ Patrick Taylor: 100 English Gardens. The finest grounds in the English Heritage Parks and Gardens Register. Falken Verlag, Niedernhausen / Ts. 1996, ISBN 3-8068-4885-8 ; P. 21.

- ↑ see in detail Ehrenfried Kuckert, Rolf Toman: Gartenkunst in Europa. From antiquity to the present. Ullmann / Tandem, Königswinter 2007, ISBN 3-8331-3500-X ; P. 204 ff.

Coordinates: 51 ° 3 '11.3 " N , 3 ° 5' 2.7" W.