Ion Keith-Falconer

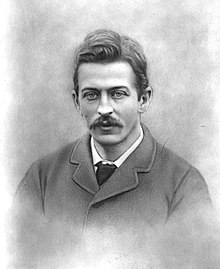

Ion Grant Neville Keith-Falconer (born July 5, 1856 in Edinburgh , † May 11, 1887 in Sheikh Othman near Aden , Yemen ) was a British theologian , philologist , missionary and cyclist . He spoke several languages, was a professor of Arabic at the University of Cambridge and a three-time national champion in cycling. In 1886 he founded a Christian mission near Aden and died there the following year, presumably of malaria .

biography

family

Ion Keith-Falconer was the third son of Francis Keith-Falconer, 8th Earl of Kintore (1828-1880), and his wife Louisa Madaleine (1828-1916), nee Hawkins. He had five siblings, three brothers and two sisters. His eldest brother was Algernon Keith-Falconer , later the 9th Earl of Kintore and Governor of South Australia . The Clan Keith performs its history up to the year 1010 back as an ancestor of the Scottish King Malcolm II. In the legendary (not historical) Battle of Barry against an invasion of Danes have successfully supported and believed to have been rewarded with land. The family was very religious and the father a prominent member of the Calvinist Church of Scotland .

In March 1884, Ion married Keith-Falconer Gwendolen Bevan, daughter and one of the 16 children of Robert Cooper Lee Bevan , senior partner of Barclays Bank ; the church wedding took place in Cannes . The marriage remained childless. After Keith-Falconer's death in 1887, his widow Gwendolen married the British officer Frederick Ewart Bradshaw in India in 1894 and had two daughters. She died in 1937. One of her sisters was the writer Nesta Webster , who was close to fascism , one of her brothers was Anthony Ashley Bevan , an Arabist like her husband, and another brother was the philosopher Edwyn Bevan .

School, training and work

Ion Keith-Falconer spent his childhood and youth at the Keith Hall family estate near Inverurie . There he and his brother Dudley were tutored by a private tutor until he attended a preparatory school in Cheam near Epsom from the age of eleven ; Dudley stayed home because of his poor health. At the age of 13, Ion Keith-Falconer switched to Harrow School . He was one of the best students there and won several prizes for his achievements in German . In 1873 he left Harrow and was henceforth taught with three other boys in preparation for his visit to the University of Cambridge by a vicar in Hitchin , primarily in mathematics , which he originally wanted to study. He also dealt with the tonic-sol-fa teaching method for singing lessons. In 1873 his brother Dudley, who had been very close to him, died in 1877, another, younger brother named Arthur.

In October 1874 Keith-Falconer began studying theology and religious studies at Trinity College , Cambridge, after which he studied Hebrew and Semitic languages . He has received several awards for his academic achievements; nevertheless, he was not considered a "nerd". In 1881 he obtained his master's degree (MA). Since he had developed a special interest in Arabic , he went to Leipzig for further studies , where, among other things, he heard lectures from Friedrich Delitzsch . In a letter he reported on the anti-Semitism in the writings of August Rohling and gave his impression that there was “general anti-Jewish agitation” in Germany. He then traveled to Egypt to learn the everyday language in addition to classic Arabic. His goal was by learning the languages to be able to compare different scriptures with one another in order to get an overall picture. He was convinced that each of the “holy writers” of biblical texts had their own inspiration and that God did not use them as mere “passive instruments” because it was God who gave them humanity and individuality. Although it is God's word , the Bible did not “fall from heaven”.

After further trips abroad, he returned to Cambridge in 1882 to create a translation of the classic Arabic text Kalīla wa Dimna from Syriac , which was published in 1885 and praised by colleagues. He was then entrusted by the university with various teaching positions and appointed as the examiner for Semitic languages. He was also asked to write a contribution to the Encyclopædia Britannica on the shorthand after Isaac Pitman , which he had taught himself as a student. He had used this writing in 1878 to record the speeches at the Ecumenical Broadlands Conference so that they could be published. When he was once writing down the sermon in shorthand in a church, the woman sitting next to him was outraged by the “naughty boy” who “painted” during the service, as he reported in a letter in 1884.

Cycling

Keith-Falconer learned to ride a bicycle while at school in Harrow, initially on a low crank wheel . As a student in Cambridge he switched to the penny farthing , was active as a cyclist from 1874 to 1882 and was nicknamed "Muscular Christian" because of his religiousness. In 1874 he took a penny farthing from Bournemouth to Hitchin over 135 miles (217 km) in 19 hours and 15 minutes (driving time approx. 16 hours) and wrote an article about it for The Field, the Country Gentleman's Newspaper . The cyclist and publicist George Lacy Hillier described this article as "one of the first in-depth reports devoted to our sport", with which Keith-Falconer made cycling popular, especially since the author had "as good a name as his".

Keith-Falconer was unusually tall for the time at over 1.90 meters. Therefore, it was easier for him than his competitors to master large high bikes, which gave him advantages in bike races. Coming from a well-to-do family, he could afford to have the best (and largest) bicycle models built for himself and to take time for training. In Cambridge he was praised as the "fastest cyclist in the world", as he set several national records. In spite of everything, he was more interested in his studies than in cycling, which for him was just a balance for his desk work. So he sometimes forgot to start in races for which he had registered, which is why Lacy-Hillier, who was otherwise only praised, criticized him as "unreliable".

Keith-Falconer recommended cycling as a means of “character building” because it “kept the young guys away from pubs, variety theaters, arcades and other traps”. He hated alcohol, swearing, and betting; so he boycotted a university competition in protest because bets could be placed on it. On May 1, 1877, he was elected President of the London Bicycling Club and remained so for nine years, which in turn spoke for his popularity with his contemporaries. He was also President of the Cambridge University Bicycle Club (CUBiC), which had its own cycling track , and was one of the founding members of the British National Bicycle Union .

In 1876 Keith-Falconer was English amateur champion in Lillie Bridge over four (6.4 km) and in 1878 over two miles (3.2 km). In October 1878 he beat professional driver John Keen at Cambridge in a two-mile race by five yards (less than 5 m); Such races “amateur against professional” were not common at the time and required approval from the newly founded Bicycle Union . Against the professional driver Frederick Cooper, however, he lost two races the following year. In June 1881 he made a 13-day tour of 994 miles (1,600 km) from Land's End to John o 'Groats , and his detailed account of the trip appeared in several newspapers. In July 1882 he contested his last important race on the grounds of the Crystal Palace near London, in which he became English amateur champion over 50 miles (80 km) and improved the existing record by seven minutes.

Faith and Missionary Work

At the age of seven, Ion Keith-Falconer is said to have given Bible readings, for which he went to farm workers in their homes without the knowledge of his family. During his student days in Cambridge, he was involved in the nearby Barnwell settlement , which had grown rapidly due to the influx of railway workers and where social injustice prevailed as a result. Together with friends and acquaintances, he raised money to convert a former theater into a mission, where church services were held regularly. He was also involved in the mission in the London borough of Tower Hamlets , an area largely populated by the poor; Not only did spiritual events take place there, but about the winter of 1879, when many people were starving, the poor were also regularly fed. He also initiated the establishment of an assembly hall there and was financially involved.

Since his school days in Harrow, Keith-Falconer had a "deeply pietist and thoroughly evangelical " desire to devote his future life to religious work. After reading an article by Major General FT Haig, a member of the Church Mission Society (CMS), in The Christian magazine in 1885, in which he called for the evangelization of the Arabian Peninsula , and after talking to the author, he decided to do so to go to Aden, administered by the British , to set up the first Protestant mission station on the peninsula. Keith-Falconer followed the example of his fellow student Charles T. Studd , who had gone to China as a missionary. The aim of his project was to establish a Christian parish for Muslim converts .

In October 1885 Ion and Gwendolen Keith-Falconer left Great Britain for Aden to settle in the Crater district , initially in a hotel. At that time, Aden was administratively part of British India and, with its location in front of the entrance to the Suez Canal, of particular strategic importance, important trade routes to and from Mecca also met there . Every morning, Keith-Falconer gave his wife an hour teaching Arabic, who was struggling with the language. He was admired and respected by the locals for his knowledge of Arabic and the Koran . He used to read aloud from the Gospel of Luke in a park in Arabic , which is why he was called the " Sāhib who speaks Arabic like a book".

After a few weeks, the couple moved to the village of Sheikh Othman, about 13 km away, because Keith-Falconer was of the opinion that he could achieve more in this rural environment than in Aden itself, but also to distance himself from the British living there and the To start proselytizing towards the north. His mission should not be seen by the locals in connection with the resident British, the British authorities and thus British imperialism . Many Arabs believed, he wrote in a letter, "that Europeans are smart people who get drunk and have no religion".

Keith-Falconer wanted to set up a school and hospital in Sheikh Othman with his own money. After a four-month stay, the couple returned temporarily to Great Britain, where Keith-Falconer was recognized as an official missionary for the Church of Scotland . He also became Lord Almoner's Professor of Arabic - a chair funded by the British Crown - at Cambridge University and gave a lecture on the pilgrimage to Mecca to explain its religious and political significance to his audience.

In late 1886, Ion Keith-Falconer returned to Yemen with his dog Jip . His wife and the young Glaswegian doctor Baruch Stewart Cowen (* 1863), who was supposed to work in the hospital, followed on other ships. Provisionally erected corrugated iron huts served as accommodation , as the landlord of a bungalow had agreed the year before, but then surprisingly changed his mind. Eventually another small house was rented and an Arab cook and two other servants from Somalia were hired. Meanwhile, a new home was being built for the missionaries. Sinker, author of the book Memorials and former tutor of Keith-Falconer, described these circumstances in detail because he wanted to refute any allegations that “the noble dead man” acted hastily or negligently.

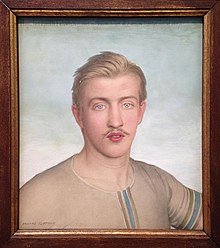

In the months that followed, Keith-Falconer and his wife had repeated fever attacks, presumably due to malaria. Nevertheless, Keith-Falconer pushed the work on the buildings and made further language studies, for example in Somali . His health deteriorated from the end of April, and on the morning of May 11, 1887, his wife found him dead in bed. That evening he was buried by Crater in the Holkat Bay European cemetery . A memorial service for him was held in the Assembly Hall in Tower Hamlets; a painting from the mid-1870s was exhibited showing him in his cycling jersey, and there was a memorial service in Cambridge.

aftermath

After Ion Keith-Falconer's death, his mother and widow Gwendolen agreed with the Church of Scotland to continue the mission and, as agreed with him, to bear the costs for several years. Cowen practiced in the hospital until 1888 and took care of the completion of the building, then he emigrated to Australia , where he died in 1948 at the age of 85 as a respected doctor. The mission, which consisted primarily of the hospital, came to be known as the Keith-Falconer Mission , and in 1897 the Keith-Falconer Memorial Church was dedicated in Aden . Keith-Falconer's goal of founding a Christian community for Muslim converts could never be achieved, even if the medical care provided by the hospital was appreciated by the local population. Already in the first months of its existence the Sultan of Lahidsch was treated there. From 1904 the Dansk Kirke-Mission i Arabien (DKM) got involved in the facilities of the mission and founded schools and workshops. It continued until the independence of South Yemen from Great Britain in 1967 and after a brief closure from 1968 to 1972.

David D. Grafton , Professor of Islamic Studies at the University of Hartford , summed up Keith-Falconer's work in 2006: His exemplary approach to proselytizing was the interest in and in-depth knowledge of Islamic traditions and the acceptance of Muslim structures. According to Grafton, Christian proselytizing - like Keith-Falconer - should not lose sight of the welfare of the Muslim community, especially in light of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 . Even if it were not possible to convert Muslims to Christianity, it would be of crucial importance to present oneself as a true Christian in the Muslim world of today, in which the gospel is often associated with Western values and imperialism. This is Ion Keith-Falconer's legacy.

Publications

- Kalilah and Dimnah; or the Fables of Bidpai: being an account of their literary history, with an English translation of the later Syriac version of the same, and notes . University Press, Cambridge 1885.

literature

- Robert Sinker: Memorials of the Hon Ion Keith-Falconer. Late Lord Almoner's Professor of Arabic in the University of Cambridge, and Missionary to the Mohammedans of Southern Arabia . George Bell & Sons, London 1890.

- James Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer of Arabia . Hodder and Stoughton, Edinburgh 1923 ( archive.org ).

- Keith-Falconer, the Hon. Ion Grant Neville . In: John Archibald Venn (Ed.): Alumni Cantabrigienses . A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, from the Earliest Times to 1900. Part 2: From 1752 to 1900 , Volume 4 : Kahlenberg – Oyler . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1951, pp. 8 ( venn.lib.cam.ac.uk Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- Andrew Ritchie: Early Bicycles and the Quest for Speed. A History, 1868-1903 . McFarland & Co., Jefferson, North Carolina 2018, ISBN 978-1-4766-3046-5 .

- James McLaren: The Church of Scotland South Arabia Mission 1885–1978: A History and Critical Evaluation . Tentmakers Publications, Stoke-on-Trent 2006, ISBN 1-901670-18-X .

- John Green: Cortis, Falconer, and the Amateur-versus-Professional Bicycling Scene of the 1880s . In: Andrew Ritchie / Gary Sanderson (eds.): Cycle History 22nd Proceedings of the International Cycling History Conference . Cycling History (Publishing) Ltd., Paris 2011, p. 34-39 .

- David D. Grafton: The Legacy of Ion Keith-Falconer . In: International Bulletin of Missionary Research . tape 31 , no. 3 , 2006, p. 148-152 ( bu.edu ).

Web links

- Keith-Falconer Mission Hospital in Sheikh Othman, Aden in Southern Arabia. Scottish mission hos .: International Mission Photography Archive, ca.1860 – ca.1960. In: digitallibrary.usc.edu. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

References and comments

- ↑ Richard Refshauge: Kintore, ninth Earl of (1852-1930). In: Australian Dictionary of Biography. January 29, 2019, accessed January 28, 2019 .

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 1.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 6.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 65.

- ↑ Arthur Bradshaw. In: oxfordhistory.org.uk. October 19, 1917. Retrieved January 28, 2019 .

- ↑ Anthony Ashley Bevan followed his brother-in-law Ion Keith-Falconer as Lord Almoner's Professor of Arabic in Cambridge in 1893 .

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 10.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 15.

- ↑ Green, Cortis, Falconer. P. 34.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 16.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 17.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 13.

- ^ Sinker: Memorials. P. 95.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 51 f.

- ^ Grafton, The Legacy of Ion Keith-Falconer , 149.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 62.

- ^ Sinker: Memorials. P. 137.

- ↑ Michael Hutchinson: Re: Cyclists: 200 Years on Two Wheels . Bloomsbury, London / New York 2017, ISBN 978-1-4729-2561-9 , pp. 99 .

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 12.

- ^ A b Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 67.

- ^ The Advertiser (Adelaide) , April 9, 1889, p. 5.

- ↑ Jim McGurn: On your Bicycle. The Illustrated Story of Cycling . Open Road, 1999, ISBN 1-898457-05-0 , pp. 61 . With this epithet reference was made to the philosophy of "Muscular Christianity", which emerged in the second half of the 19th century in Great Britain and the USA and propagated characteristics such as Christian faith, patriotism and athleticism for personal development. See veritesport.org

- ^ Andrew Ritchie: Bicycle Racing. Sport, Technology and Modernity 1867-1903 . Phil. Diss., 2007, p. without .

- ↑ a b c Green, Cortis, Falconer. P. 35.

- ^ David V. Herlihy : Bicycle. The History . Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2006, ISBN 0-300-12047-8 , pp. 186 .

- ^ Robson, Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 26.

- ↑ a b Ritchie: Early Bicycles. P. 66.

- ↑ The information about these championships is contradictory. While The Badminton Library of Cycling from 1901 and other sources provide this information, Angelo Gardellin states in his book Storia del Velocipede e dello Sport Ciclistico (p. 223) from 1947 that Keith-Falconer was English champion in 1876 and 1878 become the short haul of a mile. The information from an English, up-to-date source is to be given preference.

- ↑ Jim McGurn: On your Bicycle. The Illustrated Story of Cycling . Open Road, 1999, ISBN 1-898457-05-0 , pp. 61 f .

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 32.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 30.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 8.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 38.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 46 f.

- ↑ a b Grafton: Legacy. P. 148.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 69 f.

- ↑ Grafton: Legacy. P. 149.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 86.

- ↑ Grafton: Legacy. P. 150.

- ↑ Grafton: Legacy. P. 151.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 100 f.

- ^ University of Glasgow: Story: Biography of Baruch Stewart Cowen. In: universitystory.gla.ac.uk. June 16, 2011, accessed February 1, 2019 .

- ^ Sinker: Memorials. P. 195.

- ^ Sinker: Memorials. P. 198.

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 147 f.

- ^ Ion Keith-Falconer. Aden Airways, December 2, 2007, accessed January 28, 2019 . The cemetery has since been leveled. See al-bab.com

- ^ Edward Clifford: Ion Keith Falconer, 1856-1887. Arabic scholar, missionary and sportsman. National Galleries Scotland, accessed January 27, 2019 .

- ^ Sinker: Memorials. P. 232.

- ↑ Grafton: Legacy. P. 152.

- ↑ The Argus (Melbourne) , July 1, 1948, p. 5. In Australia, Baruch Stewart Cowen specialized in the treatment of miners suffering from tuberculosis and organized the resistance of workers against unhealthy working conditions in the gold mines of the Bendigo Mine Owners' Association , which is why he "Champion of the Eaglehawk Miners" was named; see smh.com.au . The Stewart Cowen Community Rehabilitation Center in Eaglehawk, a suburb of Bendigo , was named after him in 1998. See hnb.dhs.vic.gov.au

- ^ Adel Aulaqi: From Barefoot Doctors to Professors of Medicine. A Brief History of Medicine in Yemen 1940–2015 . Eldat Shams Medical History Publishing, Chesham, Bucks. 2017, ISBN 978-0-9956619-0-5 , pp. 32 .

- ↑ The Keith-Falconer Mission 1886-1963. In: al-bab.com. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ^ Robson: Ion Keith-Falconer. P. 153.

- ↑ Book review The Church of Scotland South Arabia Mission 1885–1978: A History and Critical Evaluation. In: al-bab.com. Retrieved January 27, 2019 .

- ^ Grafton, The Legacy of Ion Keith-Falconer , 152.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Keith-Falconer, Ion |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Keith-Falconer, Ion Grant Neville (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British scholar, missionary and cyclist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 5, 1856 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Edinburgh |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 11, 1887 |

| Place of death | Sheikh Othman near Aden , Yemen |