Nassenfels earth fort

| Nassenfels earth fort | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Scuttarensium |

| limes | ORL NN ( RLK ) |

| Dating (occupancy) | around 90 AD to 110 AD at the latest |

| Type | Cohort fort (?) |

| unit | Cohors I Breucorum (?) |

| size | approx. 1.50 - 1.70 ha |

| Construction | a) wood-earth |

| State of preservation | largely overbuilt, partly preserved underground |

| place | Nassenfels |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 47 '59.6 " N , 11 ° 13' 26.8" E |

| height | 400 m above sea level NHN |

| Subsequently | Kastell Kösching (east) |

| Backwards | Small fort of Neuburg (southwest) |

| Upstream | Fort Pfünz (northeast) |

The Nassenfels earth fort , which is also known as the Nassenfels wood-earth camp , was most likely given the name of the civil settlement Scuttarensium, which later expanded at the same location, during its existence . Nassenfels was a Roman troop base occupied for only a few decades and established by the army command at the time after crossing the Danube in the nineties of the first century AD. The complex belonging to the Raetia province developed into an important civil place located in the Limes hinterland. With the fall of the Limes around 259/60 AD and the associated destruction of the place, Roman life came to a standstill. Today nothing remains above ground of the partly extensive remains of ancient buildings in and around the Upper Bavarian market Nassenfels , district of Eichstätt .

location

The Nassenfelser area was already visited by the people of the Stone Age . On the Jura plateau of the Speckberg near Nassenfels, the largest Paleolithic open-air station in southern Germany was excavated from 1963 . During the investigation of a 3000 square meter area in the "Maueräcker" corridor, led by the archaeologist Anneli O'Neill, in autumn 2010, in addition to the expected civil post-castle findings from the early 2nd to 3rd centuries AD, Iron Age pit houses and two Graves (101 and 102) from the time of the bell beaker exposed. Their equipment included a stone arm protection plate , flint arrowheads and carefully crafted ceramics.

An important Roman expansion goal from the Danube north to the Alp and the Ries basin was certainly the development of this settlement chamber with its fertile loess soils . The Bavarian historian Johannes Aventinus (1477–1534) already reports on this vegetation . So the fort was built on good ground north over the Schutter. This flows from Nassenfels to the southeast towards the Danube, creating a direct connection for small watercraft. The garrison was at the southern foot of the Franconian Alb in the western foothills of the Ingolstadt basin.

Surname

The name Scuttarensium is derived from the Schutter flowing through Nassenfels and the valley of the same name that it formed. The name Schutter is traced back to a Celtic origin. The ancient place name was preserved by a spoil with carefully carved letters, which was walled up in the cemetery wall until 1953 and is now in the anteroom to the Catholic Church of St. Nicholas in Nassenfels, consecrated in 1741. The stone, executed as tabula ansata , was created after the end of the garrison in the 2nd century and shows a consecration to Mars and Victoria . The place name in the inscription can only be read in remnants, but the Latin name of the Schutter - Scutara - is documented for the time before the first turn of the millennium.

Marti et Victoriae

vik (ani) Scu [t] t (arienses) cur (am) ag (entibus)

C (aio) Iul (io) Impetrato et T (ito) Fl (avio)

Gemellino IMP C [o?] M III

Translation: "The inhabitants of the Vicus on the Schutter (set) (this monument) to Mars and Victoria under the direction of Caius Iulius Impetratus and Titus Flavius Gemellinus ..."

The rest of the text is debatable. The abbreviations are resolved differently by different epigraphers . In addition to imp (ensis) com (munibus) f (ecerunt) , the ancient historian Karlheinz Dietz can also imagine a consular date : Imp (eratore) C [o] m (modo) III , which would result in a date for the year 181 AD .

Research history

Generations of researchers and historians contemplated locating a fort in Nassenfels. All the evidence seemed to confirm that. At the beginning of the 20th century it looked as if tangible evidence of the garrison location had been discovered for the first time. The Imperial Limes Commission reported that during excavations in 1901 it seemed as if the location of a Roman earth fort could finally be determined. The wall discovered at that time was cut in the winter of 1911/12 during a renewed investigation, which revealed its post-Roman structure. In its depth, however, the excavators encountered a strong cultural layer with finds from the 2nd century AD.

It was not until the early 1990s that parts of the fence around the wood-earth store were finally discovered. From 2010 to 2016, parts of the northern fort area and the vicus that had remained untouched so far were completely built over by the development of a new building area in the "Maueräcker" corridor, which has been known for ancient times.

Building history

In the course of the Roman occupation of the territory downstream of the Danube, the first advanced military camps and fort chains in wood-earth construction were built. The Eining fort , which was built between 79 and 81 AD on the downstream side of the Danube, and the Kösching fort on the southern side of the Danube, dated to spring 80 AD by a building inscription, are among the very early constructions of this development Opposite was the Oberstimm fort , which was built in the forties of the 1st century AD and played an important role as a garrison site at that time.

Possibly in a second wave around 90 AD, during the reign of Emperor Domitian (81–96), further garrisons emerged in quick succession. These include Nassenfels Castle, which may have already been developed via the existing Neuburg an der Donau site . A bridge over the Danube ten kilometers west of Neuburg and south of the village of Stepperg could not be fixed until the middle of the 2nd century AD (145 ± 10, 165 ± 5) according to dendrochronological sapwood boundary dating. To the west of Nassenfels, Roman troops had already advanced much further north to secure the fertile Ries basin and had set up the Weissenburg , Munningen , Unterschwaningen and Gnotzheim forts . Pfünz Castle, northeast of Nassenfels, was possibly built at the same time . In the opinion of the archaeologist Dietwulf Baatz , among others, this location can perhaps be seen as an advanced successor to Nassenfels.

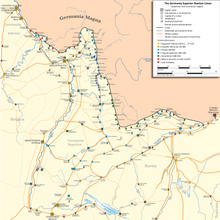

A well-developed road connected Eining with the fortifications of Pförring , a Trajan foundation, Kösching and Nassenfels, which were almost in line . From this junction in the south Neuburg and the Donausüdstraße , to the north Pfünz, Böhming , founded at the earliest during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138), and the area of Germania magna could be reached. Another route connected Nassenfels with the Oberdorf fort, which was possibly also built in the Domitian era .

Very little has been known about the wood-earth warehouse in Nassenfels that was built around 90 AD, especially its interior development. The approximately 1.50 to 1.70 hectare complex is oriented relatively precisely according to the cardinal points, whereby only the westernmost part, but there in its full north-south extension, is archaeologically accessible. The middle and eastern section of the camp is severely disturbed, among other things, by the later vicus development. Today's Geniusstraße follows the course of the southern front of the fort in its eastern section. At the end of it, you come across Winkelmannweg. This follows the old Roman route straight to the north; in the village he comes across the west-east running Roman road, which is also based on an ancient route.

Since 2001, emergency excavations have been taking place in the "Krautgartenfeld" corridor just a little west of the village in order to prevent a new settlement. The scientific director was the archaeologist Claus-Michael Hüssen from the Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), Ingolstadt branch . Among other things, numerous palisade ditches of civil buildings from the Flavian period (69–96), which obviously belonged to the early vicus of the fort, were revealed .

Troop

In the past, the Cohors I Breucorum was often accepted as a crew in Nassenfels. The unit could have been garrisoned here in Domitian times until it was moved forward to Pfünz.

Post-pastoral use

The wood-earth warehouse was leveled after its abandonment and the free space gained was used for further civil development. The archaeologist Thomas Fischer assumes the end of the camp at the beginning of the 2nd century. Of the civil buildings that were newly built at that time, a large stone building with its long sides facing west-east, which was presumably built over the area of the Principia (staff building) , could be examined more intensively. The building, which was probably built in the early 2nd century, probably served public purposes. A statue of the genius loci excavated in the rear of the building supports this thesis. The flowering of the regionally important vicus is evidenced by a large number of stone monuments from the 2nd and 3rd centuries. In the corridor Krautgartenfeld, in addition to the early Roman findings by aerial photography in 1976, a generously dimensioned villa suburbana could be observed, the courtyard wall of which covers over three hectares. From 2002 the outbuildings of this post-fortified villa were archaeologically examined.

With the end of Roman rule north of the Danube, the buildings that had remained undamaged during the Limes fall fell into disrepair - Nassenfels was evidently cleared. In the early Middle Ages, there were new settlements on the fringes of the Roman building remains. During the construction of the recycling center in 2013, twelve mining houses from the Carolingian era were uncovered. The villa suburbana could obviously have been visited again at the beginning of the 5th century. This is attested by a hallmarked belt fitting documented several times in the Raetian Danube foothills. However, the permanent resettlement of the villa area is only guaranteed from the 7th century. Pit houses and wells were also built within the remains of the building. The excavations in the Krautgartenfeld lasted from 2001 to 2006. A seven by twelve meter early medieval church was also partially uncovered. There were also outbuildings and a cemetery. Spolia from the villa was walled up in the early medieval buildings. In the 10th century the settlement of this place broke off to the present day.

literature

- Thomas Fischer , Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Pustet, Regensburg 2008. ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , pp. 186-187.

- Jochen Haberstroh : Vicus, Villa and Curtis? Excavations in the villa rustica of Nassenfels . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 2004, pp. 116–119.

- Karl Heinz Rieder : Nassenfels - Roman fort with vicus and medieval castle . In: Ingolstadt and the Upper Bavarian Danube Region (= Guide to Archaeological Monuments in Germany 42), Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-8062-1716-5 , pp. 170–173.

- Oswald Böhme: The presumed Roman earth fort in Nassenfels . In: Historische Blätter für Stadt und Landkreis Eichstätt 22, 1973, pp. 6-8.

Web links

- The topography of the fort and vicus Nassenfels near Arachne , the object database of the University of Cologne and the German Archaeological Institute; accessed on December 14, 2017.

Remarks

- ^ Ua: Friedbert Ficker: The paleolithic open-air station Speckberg near Nassenfels . In: Historische Blätter für Stadt und Landkreis Eichstätt 18, 1969, pp. 9–12; Explorations in the palaeolithic open-air station “Speckberg” . In: Bavarian history sheets 31, 1966, pp. 1–33.

- ↑ Anneli O'Neill: Two bell-shaped graves in Nassenfels . In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2010 (2011), pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Claus-Michael Hüssen : Roman occupation and settlement of the Middle Rhaetian Limes area . In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 71, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, pp. 5–22; here: p. 7.

- ↑ Johannis Aventini - The highly acclaimed and well-known Beyer historian Chronica Feyerabend, Frankfurt a. Main 1580, p. 160.

- ↑ Wolfgang Czysz , Lothar Bakker a . v. a .: The Romans in Bavaria . Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1600-2 , p. 485.

- ↑ a b Dietwulf Baatz : The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube . Mann, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-7861-1701-2 , p. 310.

- ↑ Hans Bauer: Schwabmünchen. Historical Atlas of Bavaria . Part Schwaben, series I, issue 15. Edited by the Commission for Bavarian State History at the Academy of Sciences, Laßleben, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-7696-9947-5 , p. 15.

- ↑ CIL 03.05898 ; Epigraphic Database Heidelberg ; Ubi erat Lupa (with photos) .

- ↑ Karlheinz Dietz : Comments on inscriptions from Nassenfels, district of Eichstätt, Upper Bavaria . In: Bavarian History Leaves 71 (2006), pp. 36–37; here: p. 34.

- ↑ Karlheinz Dietz : Comments on inscriptions from Nassenfels, district of Eichstätt, Upper Bavaria . In: Bavarian History Leaves 71 (2006), pp. 36–37; here: p. 35.

- ↑ Karlheinz Dietz : Comments on inscriptions from Nassenfels, district of Eichstätt, Upper Bavaria . In: Bavarian History Leaves 71 (2006), pp. 36–37; here: p. 36.

- ^ Report on the work of the Reichslimeskommission in 1901 In: Yearbook of the Imperial German Archaeological Institute 17, Reimer, Berlin 1902, p. 71.

- ^ The exploration of the Upper German-Raetian Limes 1908–1912 . In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission 7, 1912, Baer, Frankfurt am Main 1913, p. 173.

- ↑ Fort Eining at 48 ° 51 ′ 1 ″ N , 11 ° 46 ′ 15 ″ E

- ↑ CIL 03, 11955 ; more precisely: Epigraphic Filebase Heidelberg

- ↑ Kösching Fort at 48 ° 48 ′ 39 ″ N , 11 ° 29 ′ 59 ″ E

- ↑ AE 1907, 00186 ; AE 1907, 00187 ; Inscription at Ubi erat lupa .

- ↑ Hans Schönberger u. a .: Oberstimm Castle. The excavations from 1968 to 1971 (= Limes research - studies on the organization of the Roman border on the Rhine and Danube 18), Mann, Berlin 1978. p. 14.

- ↑ Fort Oberstimm at 48 ° 42 ′ 43.9 ″ N , 11 ° 27 ′ 18.49 ″ E

- ↑ Neuburg small fort at 48 ° 44 ′ 12.61 ″ N , 11 ° 10 ′ 32.5 ″ E

- ↑ Marcus Prell: Roman river bridges in Bavaria on the current state of research. In: Louis Bonnamour (ed.): Archeology des fleuves et des rivières. Editions Errance, Paris 2000, ISBN 2-87772-195-7 , pp. 65-69; Marcus Prell: The Roman Danube Bridge near Stepperg. Diving archaeological studies 1992 to 1996. Reprint from the Neuburger Kollektaneenblatt 145 (1997), pp. 1–80.

- ↑ Roman Road according Nassenfels at 48 ° 44 '27.86 " N , 11 ° 5' 9.93" O ; Römerstrasse according Nassenfels at 48 ° 44 '19.43 " N , 11 ° 4' 59.86" O ; Roman road to Nassenfels at 48 ° 44 ′ 40.3 " N , 11 ° 5 ′ 21.45" E ; Roman road to Nassenfels at 48 ° 44 ′ 50.38 " N , 11 ° 5 ′ 34.75" E ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstraße at 48 ° 44 '0.52 " N , 11 ° 4' 27.82" O ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstrasse at 48 ° 43 ′ 57.16 ″ N , 11 ° 4 ′ 23.51 ″ E ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstrasse at 48 ° 43 ′ 57.16 ″ N , 11 ° 4 ′ 23.51 ″ E ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstrasse at 48 ° 43 ′ 55.77 ″ N , 11 ° 4 ′ 22.72 ″ E ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstrasse at 48 ° 43 ′ 54.29 ″ N , 11 ° 4 ′ 14.2 ″ E ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstraße at 48 ° 43 '55.59 " N , 11 ° 4' 9.39" O ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstrasse at 48 ° 43 ′ 55.45 ″ N , 11 ° 4 ′ 4.22 ″ E ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstraße at 48 ° 43 '53.16 " N , 11 ° 3' 57.51" O ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstraße at 48 ° 43 '46.84 " N , 11 ° 3' 54.05" O ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstrasse at 48 ° 43 ′ 36.21 ″ N , 11 ° 4 ′ 0.91 ″ E ; Römerstrasse to Donausüdstrasse at 48 ° 43 '26 " N , 11 ° 4' 7.65" E

- ↑ Weissenburg Fort at 49 ° 1 ′ 51 ″ N , 10 ° 57 ′ 45 ″ E

- ↑ Kastell Munningen at 48 ° 55 '37.65 " N , 10 ° 36' 7.55" O

- ↑ Castle Unterschwaningen at 49 ° 4 ′ 10.25 ″ N , 10 ° 37 ′ 20.54 ″ E

- ↑ Gnotzheim Fort at 49 ° 3 ′ 25.9 ″ N , 10 ° 42 ′ 16.2 ″ E

- ↑ Fort Pfünz at 48 ° 53 ′ 2 ″ N , 11 ° 15 ′ 50 ″ E

- ↑ Fort Pförring at 48 ° 49 ′ 6.5 ″ N , 11 ° 40 ′ 56.5 ″ E

- ↑ Böhming Castle at 48 ° 56 ′ 46 ″ N , 11 ° 21 ′ 39 ″ E

- ↑ stamp of southern Gaul potter FLAVIVS GERMANVS on smooth Sigillata. According to Jörg Heiligmann: The "Alb-Limes": a contribution to the history of Roman occupation . Theiss, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 380620814X , p. 130 as well as list 10, no. 4 and plate 154, fig. 16.

- ↑ Fort Oberdorf at 48 ° 52 ′ 7 ″ N , 10 ° 20 ′ 30 ″ E

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Pustet, Regensburg 2008. ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , pp. 186–187 (with ill.).

- ↑ Jochen Haberstroh : Vicus, Villa and Curtis? Excavations in the villa rustica of Nassenfels . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 2004, pp. 116–119; here: p. 117.

- ↑ Wolfgang Czysz , Lothar Bakker a . v. a .: The Romans in Bavaria . Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1600-2 , p. 136.

- ↑ Thomas Fischer, Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Pustet, Regensburg 2008. ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 , pp. 186-187; here p. 187.

- ↑ Martin Luik : Castle Köngen and the end of the Neckar Limes. On the question of the post-fort use of forts in the right-Rhine Limes area . In: Ludwig Wamser , Bernd Steidl: New research on Roman settlement between the Upper Rhine and Enns (= series of publications of the State Archaeological Collection 3), Colloquium Rosenheim, 14. – 16. June 2000, Greiner, Remshalden-Grunbach 2002, pp. 75-82; here: p. 78.

- ↑ Jochen Haberstroh : Vicus, Villa and Curtis? Excavations in the villa rustica of Nassenfels . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 2004, pp. 116–119; here: p. 116.

- ^ Guided tour of the excavation , Donaukurier, April 26, 2013

- ↑ Early medieval settlement at the Nassenfels recycling center at 48 ° 47 ′ 53.11 ″ N , 11 ° 14 ′ 7.52 ″ E

- ↑ Jochen Haberstroh: Vicus, Villa and Curtis? Excavations in the villa rustica of Nassenfels . In: The Archaeological Year in Bavaria 2004, pp. 116–119; here: pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Location of the outbuilding of the villa in Krautgartenfeld at 48 ° 47 ′ 58.5 ″ N , 11 ° 13 ′ 7.06 ″ E

- ↑ Daniel Funk: Unique treasure in the ground. State Office for Monument Preservation is critical of the expansion of “Krautgartenfeld” in Nassenfels . Donaukurier, December 1, 2015