Measure for measure

Measure for Measure (Engl. Measure for Measure ) is a comedy by William Shakespeare . It is one of the so-called " problem pieces " from Shakespeare's work and was probably written in 1603/04.

Shakespeare used various elements from a story in the collection of novels Hecatommithi (1565) by Giovanni Battista Giraldo Cint (h) io or from a dramatization of this story by Cintio himself, Epitia (printed 1583), as well as from the two-part comedy Promos based on Cintio's work and Cassandra (1578) by George Whetstone .

action

For Duke Vincentio the laws in Vienna have been violated too often. In order to put a stop to the general moral decline, which he believes to have partly to blame through his own leniency in the judiciary, he appoints Angelo as governor , who is supposed to enforce the laws that were all too liberally applied until then. Vincentio apparently leaves the city, but in fact he disguises himself as a monk to watch Angelo in his office. The supposedly conscientious Angelo quickly turns out to be too weak to resist the temptations of power. This becomes clear when he tries to make an example of Claudio, a young aristocrat, who, despite a marriage vow, impregnated his fiancée Juliet before the wedding; Claudio is to be executed before nine o'clock the next morning.

When his sister Isabella learns of her brother's misfortune through an acquaintance, she goes to Angelo, kneels down in front of him and begs him for mercy for her brother. But Angelo shows no compassion at first. He just tells her to come back. But his subsequent self-talk reveals that he is sexually attracted to Isabella and desires her. When Isabella reappears before him, he offers her not to have her brother killed if Isabella indulges in him for a night. Isabella, however, indignantly refuses this offer and lets the law take precedence.

Meanwhile, Vincentio, disguised as a monk, follows the action and reveals his plan to Isabella: Angelo was once engaged to Mariana, but abandoned her because she had lost her dowry in a shipwreck. Isabella is supposed to accept Angelo's request, but her place is supposed to be taken by Mariana. Isabella then pretends to arrange a meeting with Angelo and receives two keys from Angelo to meet him in his garden at night. After swapping places with Mariana at night, Angelo succumbs to the deception and believes that Isabella has given herself to him. Nevertheless, he does not pardon Claudio and even wants to have him executed at four o'clock; Claudio's head is to be sent to him at five o'clock after the execution of the death sentence. But Claudio is not executed at Vincentio's instigation and Angelo receives the head of a gypsy who died in prison the night before.

When Vincentio takes his place again as Duke, everything clears up. Angelo confesses his crime in a court case in which he was appointed as judge by the Duke and asks for the death penalty. Instead, however, the duke pardons him and condemns him to marry Mariana. Claudio is released from prison and marries his fiancée Juliet. At the end the Duke offers Isabella the marriage; However, this leaves it open whether she will actually marry him.

Literary templates and cultural references

The motif of the “monstrous ranson” , the ransom of one's own chastity that a woman has to pay for the life of her husband or brother, or the history of blackmailed trade and pardons for sexual intercourse with subsequent breach of the agreement is a far cry in world literature widespread, old narrative material. In the 16th century alone there were seven dramatic and eight non-dramatic versions that Shakespeare might have known. Three versions of the material can be identified as Shakespeare's main sources, either directly or indirectly: first, the story of Vicos convicted of manslaughter, his sister Epitia and the imperial governor Juriste, which is the fifth novella of the eighth decade in the Hecatommithi collection by Giovanni Battista Giraldo Cint (h) io from 1565; secondly, a dramatization of this story by Cintio himself with the title Epitia , which was printed in 1583; and third, a two-part comedy by Shakespeare's contemporary George Whetstone entitled The Right Excellent and Famous Historye of Promus and Cassandra from 1578. A novella version by this author that is identical in all essentials is also in the Heptameron of Civil Discourse (1582).

Shakespeare probably used George Whetstone's Promus and Cassandra as an immediate model ; Various elements of the plot, such as the Austrian setting, the character of Escalus or the hardened criminal as a substitute for the convicted brother, he seems to have also taken from Cintio's collection of short stories Hecatommithi , which Whetstone himself had used as a source in his comedy.

The dramatic figure of the ruler in disguise was a popular figure in the early Jacobean theater and can be found in Thomas Middleton's The Phoenix (around 1603/04), Thomas Dekker's The Honest Whore, Part II or John Marston's The Malcontent (1604); It most likely has its origin in Elizabethan history drama ( history plays ), for example in Thomas Heywood's The First and Second Parts of King Edward the Fourth (around 1600).

This so-called Harun-al-Rashid motif of the adjustment of the ruler as a simple man of the people appeared in the world literature already in the collection of Oriental tales Thousand and One Nights , which in English as Arabian Nights was first printed in 1706, and was In terms of work history, Shakespeare's Measure for Measure is obviously geared towards the interest of the contemporary audience in the new King James I and his perception of his responsibility as ruler.

Shakespeare's most important change compared to his sources and templates is that Isabella, who as supplicant concludes the pact with the corrupt governor Angelo , does not really have to indulge herself by the bed trick , the nightly swap of places, and therefore consistently from an absolute position Can argue or act innocence.

The motif of the bed-trick , which Shakespeare also uses in All's Well That Ends Well , was not only widespread in the oral storytelling tradition of the time and the Italian short story literature , for example in Giovanni Boccaccio's collection of novels Decamerone (3rd day, 9th story), but had its forerunners in the Old Testament ( Genesis 38 ) and in the Amphitruo of the Roman poet Plautus .

Interpretation aspects

The focus of the play, Duke Vincentio von Vienna, is a fictional drama character invented by Shakespeare, which he has given various features of Elizabethan England. Vincentio's decision to transfer power to his deputy Angelo triggers the actual dramatic action, which Vincentio only takes back into his hands in the middle of the action in his disguise as a monk.

The delegation of responsibility to Angelo with the aim of putting a stop to the corruption and moral decline in Vienna, which Vincentio believes to have partly to blame due to his own leniency in the case law, does not necessarily represent a Machiavellian move by the Duke, as some interpreters assume . Rather, this transfer of power protects Vincentio as ruler from the accusation of tyrannical arbitrariness to which he might be exposed if he reversed his previous nineteen years of liberal government and legal practice into its opposite.

The imperative to crack down on legal practice is made clear at the beginning of the drama by the various scenes in the brothel setting of Mistress Overdone with her accomplices and customers; however, in the course of the plot, Shakespeare questions the legal rigor as an appropriate means of disciplining sexuality several times.

Vincentio's second motive for delegating power, besides enforcing the law with the necessary severity, is to examine his deputy Angelo, who is seen as an able and apparently dispassionate man. However, this concern of the Duke is only introduced as a plot later in the play.

Even the naming of Angelo contains a symbolic ambivalent meaning: On the one hand, the name refers to the almost superhuman virtue and purity of the person who bears the name; on the other hand, the term "angel" in early New English usage denoted not only an angel, but also a coin that was used during the reign from Eward IV to Charles I , which Shakespeare uses in the further course of the play for puns about counterfeiting.

In his campaign against the prevailing corruption and immorality, Angelo's approach proves to be unsuitable. During his investigation into the pimp Pompey, he shows little patience in his capacity as a judge; He leaves the research to Escalus, and then hastily condemns the young nobleman Claudio to death for reasons of general deterrence and general prevention, since his fiancée Juliet is expecting a child from him. He does not show any understanding that the young couple, after postponing the ceremony of their marriage because of an unresolved dowry issue , had anticipated the consummation of the conjugal union before their marriage was officially approved and thus recognized in public as legally valid.

Based on the information provided in the text, however, it is difficult to determine to what extent the couple's secret marriage vows were already legally valid at the time, since Shakespeare calls up the context of a long political and theological debate about public morality in England. Between 1576 and 1638 there were a total of 95 legislative proposals on this issue, which the Puritans in particular made with great enthusiasm; during the reign of Oliver Cromwell then fornication , adultery and incest were declared capital crimes in 1650 .

At the time of the creation of Measure for Measure , Angelo's decision is obviously to be classified as extremely rigorous based on the assessment at the time, especially since both Lucio and Provost express their pity for the condemned. Angelo, on the other hand, insists on an objection from Escalus that he would sentence himself to death in a comparable case; As the further course of the plot shows the audience, Shakespeare unmistakably employs the means of dramatic irony in massive form .

Angelo's hostile rationality and literal faithfulness to the law, which the Duke had previously expressly authorized to interpret, collapse the moment the novice Isabella asks for mercy for her brother. Angelo now has to experience for himself that he has sexual desires, which Isabella triggers in him precisely because she embodies a female equivalent or a female alter ego for him in her chastity, virtue and moral rigor . He also has to find that he does not want her as a spouse, but clearly has a desire to dirty or rape her. Although he is terrified of this diabolical side in himself, this does not prevent him from demanding Isabella's unconditional devotion as the price for her brother's life.

In contrast to Shakespeare's literary models in Cintio and Whetstone, Isabella in Measure for Measure is not a balanced or mature woman who is knowledgeable about life, but rather young and inexperienced; she would like to see even stricter religious rules for the convent she wants to join . Therefore she rejects Angelo's request full of indignation and hopes for Claudio's approval or at least his understanding for her decision to put the value of her own chastity above that of his life. At the same time, in this context, she explains quite credibly that she would be ready to die a martyr 's death at any time to save her brother's life, even though her slightly erotic- masochistically exaggerated assurance arouses doubts about her asexuality . In addition, she overlooks the fact that Angelo does not seek her life, but only desires her body. When Claudio, despite his earlier determination to die a manly death, shows a creatural fear of death in view of the possibility of saving his life, Isabella reacts excessively cool and extremely callous.

A tragic outcome therefore initially seems inevitable; only the presence of the duke disguised as a monk prevents an irrevocably tragic development. Since the audience, in contrast to the characters in the drama, is aware of the secret presence of Vincentios, who appears incognito as a monk, from the start, the audience is guaranteed a happy outcome from the outset, with the worst in the play is avoided.

The motif of the ruler in disguise, also known in world literature as the Harun-al-Rashid motif , was very popular in English drama at the beginning of the 17th century; As in the various disguised ruler plays by John Marston or Thomas Dekker, Shakespeare also speaks to an interest of his contemporary audience, who asked themselves how the new ruler James I would exercise his governmental responsibilities in the future.

In order not to have to give up his incognito to save Claudio's life, the duke is forced to resort to the bed-trick : Angelo's former fiancée Mariana takes Isabella's place at the nightly get-together. Vincentio puts Angelo in the same situation for which Claudio has been sentenced to death, since Angelo is now sleeping with a woman to whom he had previously promised marriage.

In order to beat Angelo at his own gun, Shakespeare consciously accepts various improbabilities in the course of the plot and the development of the character. Similar to All's Well That Ends Well , Angelo is brought to the knowledge of his guilt in a cleverly staged court case. While still in disguise, the duke appoints his governor to judge his own cause, who then convicts himself.

Even the title of the piece alludes to the biblical warning in Matthew - Gospel (7.1-5) to not to judge, not to be directed at himself. Angelo now has to experience that he has disregarded this warning: He is now threatened with death as the measure that he himself used in the case of Claudio. While Claudio actually loved his fiancée, Angelo only sought sexual satisfaction in his relationship with Isabella, which he even wanted to rape. In addition, he gave orders to kill Claudio even though he believed he had slept with Isabella and was not even willing to keep the pact that had previously been made.

After convicting himself in the court case, however, Angelo ultimately shows enough insight to demand the death penalty twice for himself. Vincentio then pardons him to marry Mariana on the condition that both Mariana and Isabella intercede for him. Although Isabella has to assume at this point that Angelo had her brother killed, she brings herself to speak up for Angelo. This indicates a change in the character drawing of Shakespeare's protagonist, which is also expressed in her public confession to the shame that she did not actually incur, but that could be attached to her in the future. At the end of the play, the duke finally offers her marriage to reconcile and restore a just order; Since Isabella does not answer this explicitly, it remains to be seen whether she will accept Vincentio's offer.

Measure for Measure ends with a multitude of marriages: Angelo marries Mariana and Vincento possibly Isabella, Claudio marries Juliet, and courtier Lucio is married to prostitute Kate Keepdown. This multiplication of marriages at the end has been interpreted time and again by numerous interpreters of the work as a parody of Shakespeare on the conventional end of comedy as a genre . Above all, the last marriage is understood in such an interpretation as a punishment that breaks apart from the genre, since the Lucio concerned expressly considers this marriage to be worse than a flogging or execution. According to such an interpretation, Duke Vincentio, through the forced marriage, petty-mindedly avenges himself for Lucio's imaginative slander against which he could not defend himself in his disguise as a monk. From the point of view of the time, however, this would be an extremely mild punishment for the offense of lese majesty .

While for Claudio and Mariana the wedding means an official confirmation of their love for each other, also in public, the marriage of Angelo and Mariana at best represents the possibility of a new beginning and thus reminds of the end of All's Well That Ends Well , which also includes the attempt a reconciliation and a new beginning.

In its dramatic structure, Measure for Measure is structured by a complex of topics in which questions of sexuality, law and grace as well as authority and power are linked. In this respect there is a thematic relationship between the piece and The Merchant of Venice . Since the genre boundaries between drama and other public discourses were still comparatively open at that time, it can be assumed that both the contemporary audience and the royal court saw corresponding statements in the play in relation to the public discussions on these questions.

In his role as ruler incognito, Vincentio prevents the potentially disastrous consequences of the separation of crown and state, but is forced, within the framework of the absolutist model of rule, to which James I also admitted with increasing clarity, to recognize his own complicity in the disastrous behavior of the people . The dangers that threaten the state and society in Vienna come primarily less from the subjects and more from the officials and those in power.

The interpretation of the ruling figure in Measure for Measure in Shakespeare's research turns out very differently on this background. Vincentio in his role as ruler is not only interpreted positively, but is also often understood as a power man in the Machiavellian sense, who is accused of abuse of power, intrigue , sadism and, with regard to Isabella, patriarchal sexism .

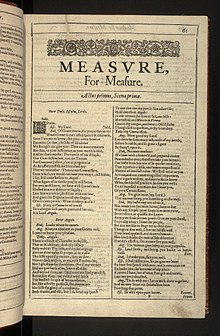

Dating and text

According to the entry in the account book of the Master of the Revels , the first performance of a play with the title Mesur for Mesur by a poet named Shaxberd on Boxing Day 1604 at the court of James I in Whitehall is attested by His Majesty's Players , i.e. by a troupe in the Shakespeare was a partner and actor.

Like other plays, of which a court performance has been passed down, the play was in all probability not written specifically for this purpose, so that in Shakespeare research it is generally assumed that the work was written as early as 1603/04.

As the earliest text version of Measure for Measure, only a print in the first folio edition from 1623 is preserved. For a long time the reliability of this print edition was disputed; some passages are obviously corrupted and the question of possible cuts or revisions by other authors or editors is very difficult to clarify.

It is largely unanimous that the immediate model for the print was a copy by the professional scribe Ralph Crane, whose work can be seen in the peculiarities of spelling and punctuation . It is unclear, however, whether Crane copied the uncorrected draft version of Shakespeare (so-called foul paper or rough copy ), or whether his copy was based on a revised version of the original manuscript that had been changed by interventions by someone else. The majority of the newer editors assume that a rough copy of Shakespeare provided the template for the copy of Cranes. Most of the errors and inconsistencies in the surviving text, such as contradicting time specifications, incomplete stage directions or uncorrected double versions, are therefore attributed to typical peculiarities of Shakespeare's draft versions.

Reception history and work criticism

Measure for Measure , which was initially devalued as dark comedy in Victorian literary criticism , has since the beginning of the 20th century under the influence of Ibsen's or Shaw's so-called “problem pieces” from the younger Shakespeare criticism in a new, understanding-promoting perspective without, however, reducing the differences in the interpretation of the work or even reaching a consensus on the meaning of the piece.

The work is regarded as an outstanding paradigm for problem play if only because the assignment to a specific genre or group of works proves to be problematic. On the one hand, the happy ending seems too forced in many ways or too much owed to the mere conventions of the classic comedy ending to actually turn the piece into a comedy. Above all, the tragic value conflicts or ambivalences of the main characters are presented with too much urgency for the playful resolution with the help of the cunning deus-ex-machina intervention of the disguised duke to ultimately convince. On the other hand, the piece cannot be understood as a pure tragedy due to the broad spectrum of different stylistic elements, which, in addition to sacred debates about sin and atonement or justice and grace, also include an abundance of grotesque brothel and prison scenes.

Accordingly, the assessment of whether the behavior of the main characters, especially the Duke and the protagonist Isabella, should be understood as positive or should be condemned, is particularly controversial in the history of interpretation. Likewise, in the analysis of the work, opinions differ as to whether the various elements of the piece as a whole even form a dramatic unit. Various interpreters still assume that this work as a whole will be divided into a first half with debates and reflections and a second action-dominated half. Nor has it been possible to reach agreement so far as to whether the piece in its overall statement is an allegory of Christian beliefs about guilt and grace or a pessimistic rejection of the Christian doctrine of salvation .

The only general consensus among the current criticism is the assessment that this piece is both a relevant and fascinating work that repeatedly challenges its recipients to re-examine.

By contrast, until the end of the 19th century the work was largely ignored or at least severely neglected in Shakespeare research, as the design of its characters and thematic aspects seemed strange to a large number of critics.

By the middle of the 20th century at the latest, however, a similarly intensive examination of the work began, as was previously only observed in Shakespeare's great tragedies, such as Hamlet , Othello , King Lear and Macbeth . While the assessment by the renowned English literary scholar FR Leavis from 1942 that the play was one of the “greatest works in the Shakespeare canon ” was for a long time considered a “blatant outsider opinion”, this judgment is now shared by almost all Shakespeare interpreters today.

In the recent history of the reception of the work, a radical re-evaluation or rediscovery of the original status is now called for, with the abundance of interpretive contributions growing steadily and meanwhile hardly being overlooked. However, according to the well-known German Shakespeare researcher Ulrich Suerbaum, this increased renewed interest in Measure for Measure in the current discussion has only led to a deeper understanding of the work to a comparatively small extent.

In retrospect, the predominant method of character analysis in Shakespeare's interpretation at the beginning of the 20th century faced major problems in this piece from the start, since Measure for Measure can only be accessed to a very limited extent , if at all, through a psychological interpretation of the characters involved is. All three main characters ultimately remain a mystery as characters, since Shakespeare only provides very sketchy character-related information in his work. Despite the long role that he plays, the duke usually only appears in disguise, but not in his actual role. In addition, Isabella reveals little about herself in the piece: the self-portrayal of the main characters in the form of a dramatic monologue, which is common in other works , is completely missing here. The statements about the motives or intentions of the other characters are either very poor or even unreliable, such as Lucio's absurd accusations against the duke.

In addition, there are actual or apparent contradictions between the general character drawing and the respective specific appearance of the characters in certain situations. For example, it is difficult to understand why the duke, who is designed as a noble figure, transfers the restoration of the corrupt or desolate order in his state to another figure and also gives the impetus for the offensive intrigue of the bed trick . Isabella's harsh or reckless behavior towards her brother in the prison scene is just as implausible. The sudden change in Angelo, initially portrayed as virtuous and principled, is hardly conclusive from a psychological point of view. The attempts to explain or justify the behavior of the main characters in this regard mostly relate to a very narrow text base and are therefore not very convincing as a whole.

In the middle decades of the 20th century, therefore, the method of thematic interpretation was increasingly chosen as an alternative to the character analysis approach in the work interpretation. As the first authoritative exponent of such a development of the work, George Wison Knight, in his famous interpretation volume on Shakespeare's dark tragedies, The Wheel of Fire , demanded a shift in the interpretation from the behavior of the characters to the central theme of the work, which he described in Measure for Measure in 1930 Essentially saw in the relationship between the moral nature of man and the bluntness of human justice.

In the subsequent interpretations in terms of reception history, concepts such as forgiveness or sexuality and domination were increasingly brought to the fore when determining the central theme of the piece. In the further history of interpretation, this spectrum of relevant topics was then expanded further. Although the approach of a thematic development has basically proven to be quite profitable for Measure for Measure and has contributed to making previously incomprehensible moments explainable, a conclusive overall interpretation of the work is still missing.

According to Ulrich Suerbaum, the previous development in the history of interpretation has even led to the fact that this Shakespeare drama has been increasingly reinterpreted "from a play that is problematic for reception to a play about problems".

In the more recent discussion, despite the progress made in thematic interpretation, the limited suitability of this approach for a coherent overall analysis of the work is emphasized. On the one hand, numerous performers in this direction have primarily brought their own topics or their own terminology to the piece without relying on the terms or concepts available there. On the other hand, such a theme-related interpretation approach only takes into account the specific dramatic form of the work to a limited extent, or not at all: The characters in the play are seen here less as independent actors and actors, but rather as mere representatives of certain conceptions or points of view.

For example, according to Suerbaum, Measure for Measure is not just about justice and grace, but about basic human action options, whose individual freedom to act is restricted by laws. Freedom of action based on self-determined will and self-set goals exists only where legal regulations do not exist or are inactive. Thus, man tends, as Measure for Measure shows to inherently the granted freedom toward licentiousness ( license ) or vice ( vice exploit), especially in the area of sexuality that the in Shakespeare's work as a paradigm for both the problem free action as well as legal regulation can be seen. The questions that arise in the course of the play are aimed at the extent to which the state or the ruler must intervene in the freedom of action of its citizens or subjects so that it does not degenerate into licentiousness or arbitrariness. This implies the problem of the relationship between the state's restriction of freedom ( restraint ) and the individual's own self-discipline. Also connected with this is the question of the extent to which the ruler, who is responsible for statutory regulation and punishment, is free in his own actions or is equally subject to precisely these restrictions.

It is precisely these questions that are dramatically problematized in the play, in that all the main characters are confronted with alternative challenges or tasks that are in contrast to their previous role in life. In this respect, the first scenes of the piece can be understood as educational games in which the protagonists discuss, reflect or practice their new roles, which they partly actually perform in their respective actions, partly only in imagination.

In addition, the extensive debates or discussions, which are mostly used by the subject interpretations as evidence for their respective interpretations, are dramatic acts, partly in the form of real and partly also imaginary actions. Accordingly, for example, in the supplication scene (II, 2) in which Isabella stands up for her brother, three different levels of action can be distinguished. First of all, the rational, initially cool discourse is about the pros and cons of a pardon; On a second level, Isabella and Angelo harass each other by playing for the opponent in what way they would behave in the role or position of the other. On a third level, there are abstract concepts such as faults , mercy , the law , authority and modesty , which are presented or symbolized in the dialogue as acting persons.

After the phase of theme interpretations of the work, there has been no further development of a dominant or closed approach to an overall interpretation in the literary examination of the piece. The view that Shakespeare deliberately designed Measure for Measure in a complex, by no means unambiguous structure, so that this piece neither contains a riddle with a hidden solution, nor an experiment with it, is predominantly represented in the various interpretations and analyzes in the critics of the last decades a clear result or a parable used to illustrate or dramatically present a particular point of view or conception. Instead, the openness and complexity of the work is emphasized, raising questions that would be answered ambiguously and juxtaposing positions, such as the Angelos and Isabellas, that would turn out to be incompatible and indefensible. In the same way, Shakespeare brings characters onto the stage that the recipients cannot meet with undiminished sympathy or with full rejection or distancing.

Despite these recent attempts by literary criticism to focus on the openness and complexity of the various parts of the play, the current criticism of Shakespeare still has its problems of developing an appropriate understanding of the work and of grasping more than just partial structures.

In terms of stage history, Measure for Measure, in contrast to the controversial reception in literary studies and criticism, was hardly seen as difficult to play or in need of adaptation; However, it was not until the 20th century that the play met with greater interest from the theater audience.

Before the restoration period , apart from the court performance mentioned above, no other performances can be proven; In 1662, an adaptation of William Davenant was played as The Law against Lovers with unmistakably comical features. In Davenant's makeover, Isabella is only put to the test by Angelo and in the end he is married. In addition, the lovers Beatrice and Benedikt from Much Ado About Nothing are built into his version in order to reinforce the genre features of the comedy.

Around 1700 Charles Gildon designed Measure for Measure, Beauty the Best Advocate, a version that came closer to the original. From 1720 onwards, in terms of theater history, a return to Shakespeare's original version prevailed; In the performances of Thomas Guthrie in 1930 and 1933 and the much-vaunted production by Peter Brook in 1950, the current references to the work were particularly emphasized. While Vincentio and Isabella were presented as ideal characters in the performances until after World War II , the political and social implications of the plot were also emphasized in later productions, for example by Jonathan Miller or Charles Marowitz. In a 1991 performance by the Royal Shakespeare Company , Trevor Nunn staged Measure for Measure in the style of Ibsen and interpreted Angelo as a study of sexual repression. Male self-image was also questioned in a performance by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1983/84.

The text was first translated into German by Christoph Martin Wieland 1762–66; further translations followed by Friedrich Ludwig Schröder in 1777 and as part of the Schlegel - Tieck edition (1839/40). The first musical adaptation was the comic opera Das Liebesverbot by Richard Wagner in 1836, based on Shakespeare's Measure for Measure . In 1936, Bertolt Brecht used the core plot of Shakespeare's play in The Round Heads and the Pointed Heads , a drama about the conflict between rich and poor.

Since the time after the Second World War, Maß für Maß has been one of the most frequently staged Shakespeare dramas in Germany, with the play initially being staged as a mystery play of grace, while later productions focus on the process of experience of the main characters and the dangers of power. Peter Zadek's iconoclastic staging in Bremen in 1967 turned this criticism of power into a provocation.

The attractiveness and charm of Measure for Measure for the modern stage lies in particular in the theatrical ambiguity and the most diverse display options that the work offers for a staging without having to brush the text against the grain.

In this regard, for example, Duke Vincentio was a wise, benevolent, god-like figure in Brooks' first production, whereas Zadek brought the Duke onto the stage as an evil, power-abusing character who plays with people. Adrian Noble, on the other hand, showed Vincentio in his production as an autocratic but enlightened ruler who ruled Vienna in the 18th century.

Text output

- English

- JW Lever (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The Arden Shakespeare. Methuen, London 1965, ISBN 978-1-9034-3644-8

- NW Bawcutt (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 978-0199535842

- Brian Gibbons (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-67078-4

- German

- Walter Naef and Peter Halter (eds.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. English-German study edition. Stauffenburg, Tübingen 1977, ISBN 3-86057-546-5

- Frank Günther (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 978-3423127523

literature

- Hans-Dieter Gelfert : William Shakespeare in his time. CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65919-5 , pp. 337–343.

- Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells (Eds.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2nd Edition, Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , pp. 294-296.

- Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare Handbook. Time, man, work, posterity. 5th, revised and supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 448-454.

- Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Reclam, Ditzingen 2006, ISBN 3-15-017663-8 , 3rd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 178-188.

- Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, ISBN 0-393-31667-X .

Web links

- Measure for measure - in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Measure for Measure by William Shakespeare - English text edition in the Folger Shakespeare Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 448. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : Der Shakespeare-Führer. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 180 f. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 294.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 448 and 450. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : Der Shakespeare-Führer. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 180 f. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 294. See also Brian Gibbons (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-67078-4 , Introduction , pp. 6 ff. See also JW Lever (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The Arden Shakespeare. Methuen, London 1965, ISBN 978-1-9034-3644-8 , Introduction , pp. XXXV ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 449. For the further meaning of the term “angel” in Early New English as a coin, see the information in the Oxford English Dictionary , online at [1] . Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ↑ See as far as Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 448 f. See also in more detail Brian Gibbons (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-67078-4 , Introduction , pp. 1 ff. See also JW Lever (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The Arden Shakespeare. Methuen, London 1965, ISBN 978-1-9034-3644-8 , Introduction , pp. XLVii ff. And Lxxxiii ff.

- ↑ See as far as Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , pp. 449-452. See also JW Lever (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The Arden Shakespeare. Methuen, London 1965, ISBN 978-1-9034-3644-8 , Introduction , pp. XLVii ff. And Lii ff. And Lxxviii ff.

- ↑ See Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 452. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 295 f. See also JW Lever (ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The Arden Shakespeare. Methuen, London 1965, ISBN 978-1-9034-3644-8 , Introduction , pp. XLix ff. And Lxiii ff. And xci ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 448. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : Der Shakespeare-Führer. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 180 f. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. 2015 edition, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 294.See also Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. corrected new edition. Oxford 1997, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , p. 468. See also Brian Gibbons (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-67078-4 , Introduction , p. 1. See also NW Bawcutt (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1991, ISBN 978-0199535842 , Introduction , pp. 1 ff. Also JW Lever (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The Arden Shakespeare. Methuen, London 1965, ISBN 978-1-9034-3644-8 , Introduction , pp. XXXI ff.

- ↑ Cf. Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 448. See also Ulrich Suerbaum : Der Shakespeare-Führer. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 180 f. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. 2015 edition, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 294.See also Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor : William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. corrected new edition. Oxford 1997, ISBN 0-393-31667-X , p. 468. See also Brian Gibbons (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-67078-4 , Introduction , p. 202. Likewise JW Lever (Ed.): William Shakespeare: Measure for Measure. The Arden Shakespeare. Methuen, London 1965, ISBN 978-1-9034-3644-8 , Introduction , pp. XXXI ff. And Lxii ff.

- ↑ See as far as Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 181, and Manfred Pfister : Staged Reality: World stages and stage worlds. In: Hans Ulrich Seeber (Ed.): English literary history. 4th ext. Ed. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-476-02035-5 , pp. 129–154, here p. 153.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 181 f.

- ↑ See Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 182.

- ↑ See as far as Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 183f.

- ↑ See G. Wilson Knight: The Wheel of Fire. Interpretation of Shakespeare's Tragedy . Meridian Books, Cleveland and New York, 5th revised and expanded edition 1957, new edition 1964 (first edition Oxford University Press 1930), pp. 73ff., Accessible online in the Internet Archive at [2] . Retrieved July 26, 2017. G. Wilson Knight regards the work at this point as “a studied explication of a central theme”. See ibid., P. 73. See also in detail Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 184 f. A detailed description of the early history of interpretation of the work can also be found in the contribution by Ulrich Suerbaum: Shakespeare-Wissenschaft aktuell? In: Shakespeare-Jahrbuch West 1978-79, pp. 276-289.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 185.

- ↑ See in detail Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 185 f.

- ↑ Cf. Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , p. 186 f.

- ↑ See as far as Ina Schabert : Shakespeare Handbook. Kröner, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 , p. 452 f. See also in detail Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. 3rd rev. Edition. Reclam, Ditzingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-020395-8 , pp. 186-189. See also Michael Dobson , Stanley Wells : The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2nd rev. Edition 2015, ISBN 978-0-19-870873-5 , p. 296.