Min-Fest

| Min festival in hieroglyphics | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old empire |

Heb-ef-en-Min-peret ḥb = fn-Mnw-prt Coming out / extracting the min |

|||||||||

| Middle realm |

Heb-ef-en-Min-peret-em-per ḥb = fn-Mnw-prt-m-prw Min moving out to his house |

|||||||||

| New kingdom |

Heb-ef-en-Min-peret-em-chetiu ḥb = fn-Mnw-prt-m-ẖtjw Excerpt of the Min to the place (house) of the stairs |

|||||||||

| Excerpt of the Min to the "stairs of Amun" in Karnak | ||||||||||

The Min feast (also excerpt of Min to his house , excerpt of Min to the house of the stairs ) was a religious celebration to the worship of the ancient Egyptian god Min and has been in the Old Kingdom since the 4th Dynasty (from 2639 to 2504 BC .) under the name "Extract of Min". The texts that exist in this period refer to the origins of the early dynastic period , when the Min festival is initially characterized as a grain offering in the representation of the white bull as the rebirth of the deity Osiris .

In the festival lists of the Old Kingdom, the Min festival was the end of the calendar of major festivals. In the course of the history of Ancient Egypt , there was a clear change in meaning in the orientation of the Min festival.

In the 18th Dynasty (from 1550 to 1291 BC), which was counted as part of the New Kingdom , there were changes in the festive rites. At the latest from Pharaoh Amenemope's accession to the throne (996 BC) in the 21st dynasty , the respective ruler sees himself in the role of a white bull and in this context as Min-Amun. The complete change of the original character of the Min-Festival has been completed; the old tradition of the Min festival ends with the beginning of the 21st dynasty and is continued with the new Min Amun festivals.

background

The deity Min experienced different symbol assignments in Egyptian mythology and was therefore later merged with several other deities. The connection between Amun-Re and Min to Amun-Re-Kamutef ("Amun-Re, bull of his mother") is documented for the first time in the Middle Kingdom . In the second intermediate period (from 1648 to 1550 BC) the special forms Min-Amun, Amun-Min ("Min-Amun / Amun-Min, bull of his mother") and Min-Kamutef ("Min, bull of his mother ") followed "). At the beginning of the 18th dynasty (1550 BC), Amun-Re-Kamutef merged into Kamutef ("his mother's bull"). Finally, in the 21st dynasty at the latest, Amenemope (“Amun of Karnak”) was added as a new statue deity, which was derived from Kamutef.

Dating

| Ju-pesdjenet-em-duat in hieroglyphics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old empire |

Ju-pesdjenet-em-duat Jw-psḏnt-m-dw3t New moon festival in the Duat |

||||

| New kingdom |

1-nu-schemu 1-nw-šmw First month of the Schemu period |

||||

The oldest documents from the 4th Dynasty refer to the heading Min festival in the season Schemu ; In the festival calendar of the sun sanctuary of Niuserre , the Min festival is also recorded for the Schemu season, but without specifying an explicit date. Only in the calendar of Medinet Habu (MHK 1430) the Min festival is unique in the 11th Schemu I dated. The reference to the link to the civil administrative calendar was an additional provision . At the same time, the Min festival is scheduled in the ancient Egyptian lunar calendar . It is also noticeable that at other lunar festivals there are no corresponding additional information for the civil administrative calendar.

The often-mentioned view that the Min-Fest was celebrated on a fixed day in the civil administrative calendar as well as on a specific lunar month day is on the one hand contradicting and on the other hand not possible in practice. The only explanation is the assumption that the 11th Schemu I represents the date in the civil administrative calendar in the year of the first reformulation. Presumably this part of Medinet Habu's calendar is a copy of the calendar in the Ramesseum .

The termination then relates to the epoch of Ramses II , in which the 11th Schemu I coincided with a new moon day ; especially the ninth, 34th and 59th year of government come into question. In the reign of Ramses III. In the third year of the reign, new moon day and Schemu I coincided; at the same time represents the third year of Ramses III's reign. the last possible formulation in the calendar.

A further indication arises from the dean lists of the Sethos script , in which Sebeschsen , the star of Min, entered the Duat on the 6th Schemu I on the body of the groove and the decreed arrangement under Sesostris III as a dating basis . ( 12th Dynasty ) in the seventh year of his reign. Under Ramses III. the date shift by five days of celebrations is known; for example at the Opet festival , which was postponed from the 14th Achet II to the 19th Achet II.

In Greco-Roman times , two processional processionals for the first and 15th Schemu I to the “ birthplace of Min-Amun ”, which also refer to the connection to the new and full moon , are documented if the festivities are appropriately assigned to the lunar calendar . In the chronocrat lists , the corresponding days of the Egyptian administrative calendar shifted from the 17th Peret II to the 19th Schemu II, since the Egyptian calendar was incompatible with the Sothis lunar calendar . The changes in the fixed dates in the Egyptian administrative calendar are also well documented in the Tebtynis lunar calendar .

In Egyptology , the seasonal connection of the Min festival with the upcoming harvest is undisputed, which is why, according to the consistently mentioned Schemu appointments in the Sothis lunar calendar, the lunar month Renutet as equation with February represents the calendar framework as the fixing date for the celebrations.

Character of the Min-Fest

The Min-Fest took place in camera and is therefore different from the large public processions that require a long distance to meet the demands of the cheering population. In contrast, the Min-Fest only includes a short procession that starts at the temple chapel and ends there again soon.

Due to the lack of public, the Min-Fest shows the character of daily rituals for the care and feeding of idols that take place in the hidden temple areas. Bar processions are therefore completely absent. An accompanying cheering population would be inappropriate for the deity Min, since Min is the god of new formation and the growth of the vegetable kingdom. He acts alone in a protected intimacy .

The incompatibility with a public procession stems from its lunar character and the associated light intensity with cosmic forces . The Min festival is connected with the task of the god Min to guarantee the original creation as well as to protect the inheritance of Osiris and to pass it on to Horus . These tasks can only be performed in the seclusion and darkness of his temple chapel.

Previous interpretations

The Egyptologist Alexandre Moret identified the white bull with Osiris, who was killed in order to rise again . The grain offering symbolizes the spirit of fertility, which has as its content the return of a strong successor. In equating Horus , who became worldly ruler through the murder of his father Osiris by Seth , the sacrifice of the white bull is said to guarantee the existence of kingship.

Similarly meadow interpreted Egyptologist Henri Gauthier grain sacrifice of a white bull, who was killed at the end of the festivities. This notion is still the subject of many literary descriptions. According to previous opinions, the procession of the white bull represented the third part of the Min-Fest liturgy, which took place at the same time as a second procession in which the statue of Min was carried along. At the end of the third part, the priesthood sent four birds in the four directions. This was followed in the fourth part by the white bull handing over a bundle of corn ears to the king. The simultaneous sacrifice of the white bull after the ears of corn were handed over was understood as a guarantee of a successful harvest for the upcoming harvest season.

The assumed sequence of rituals is based on a text that cannot be linked without contradiction to the pictorial scenes depicted. The Egyptologist Émile Chassinat points out the circumstances that a sacrifice of the white bull is not mentioned in ancient Egyptian texts and that iconographic representations of the bull sacrifice are missing. In connection with the course of the procession, if the images are interpreted precisely, problems arise in interpreting them as killing. As a result, the older explanations mostly available in Egyptology are mainly based on the theories of the Myth and Ritual School , which were represented in particular by Alexandre Moret.

New investigations

Slaughtering the white bull in the interior of an ancient Egyptian temple is almost impossible according to the current state of research, since animals were examined by the priests for divine evidence before they were slaughtered as sacrifices to God and killing was unthinkable if a sign was seen. No ancient Egyptian text gives detailed information about the execution and type of ritual slaughter.

Due to new investigations of the liturgical texts , the previous interpretations seem unlikely, since the white bull also played an important role in royal ideology and was understood as a mediator of royalty. The life of the white bull symbolized the life and continuation of the reign of the respective king as well as the determination of his heir to the throne.

Supplementary descriptions of the pictorial representations as well as newly found parallel texts and festival descriptions from temples of gods in Greco-Roman times can also no longer confirm earlier interpretations and interpretations of the Min-Festival in their previous form. There is now a new and clear sequence of rites that move the white bull into the center of the Min festival.

Festive course

opening

At the beginning of the festival, the priests carried the king on a sedan chair from his palace, which was located in the New Kingdom near the Amun temple in Karnak . Before the procession started, the king spoke the opening words: "Because of the beauty of his father, may the king be carried to him on his beautiful feast on the stairs to make an offering to his ka ". In addition to the King and the Great Royal Wife, the king's sons, the guards, and a limited number of officials and priests were present.

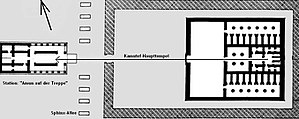

In addition, two Anubis jackals as "openers of the ways" and the statues of the royal ancestors formed the entourage. After the gates of the tenth pylon of Karnak had passed, the procession along the Sphinx avenue reached the temple of Kamutef .

Arrival at the temple of Kamutef

The king, who was already expected in the Kamutef temple, stepped to the holy divine shrines (rooms 9 to 11) . Immediately in front of these rooms, the “Holy of Holies”, stood the statue of Min, which was attached to a support frame and which was symbolically transported only a very short distance into the small transverse hall (room 8). In the small chapels (rooms 5 and 7) were probably the important cult objects “ God's shadow ” and “ Lattichgarten des Min”, which were later integrated into the procession.

According to the representations of Medinet Habu , the priesthood consecrated the ithyphallic statue of the god Min during parallel sacrifices that were prepared in the open sun courtyard (room 3). The offerings are described in more detail in the texts: "Cattle, beer, wine, geese and other good things". Accordingly, the drink and burnt offerings were freshly prepared in the Sonnenhof. In addition, the air was soaked with clouds of incense .

The subsequent transfer of the heavy stone statue on a support frame is difficult to imagine, as the door openings were only one meter wide and only a few priests were allowed to touch the statue of the gods. On representations of the Min festival from the reign of Ramses III. the statue of God is symbolically supported by a priest with a long, thin pole and a small statue of a king, which would be impossible if it were made from solid stone. Therefore, it must have been a wooden statue that was in the forecourt (room 1) from the start and was decorated for the further procession in the columned hall (room 2).

After the drink and burnt offerings, the Sem priest anointed the wooden statue in the forecourt and ritually cleansed it in another consecration. Many of the pictures show how the king personally supported the statue. At the time of the anointing of the gods, the white bull was still in his own cult temple and was prepared for his task in the extension of the Kamutef temple after the sacrifices were over.

Further course

The white bull is characterized by black fur on the left temple, which identifies it as the sacred animal of Min. In addition, it is decorated with two feathers from the sun crown, the neck is decorated with a valuable embroidered red cloth. The white bull represents the link between the moon and the sun and thus symbolized Horus in the horizon , who personified the rising sun. He merged with Chepri as a symbol of eternal life and resurrection.

The fourth part was opened by the procession of the white bull in the courtyards of the annex to his cult temple, which was followed by the further procession of the statue of the gods. In the sixth part the priesthood solemnly cut off a bundle of ears of corn in front of the white bull in order to receive the benevolence of the white bull for the upcoming harvest and the renewal of the royal rule.

This was followed by the shooting of arrows and the raising of birds in the four directions. The eighth part of the procession ended with the return of the Min statue with accompanying incense and libations in the temple chapel.

literature

- Arne Egberts : In quest of meaning. A study of the ancient Egyptian rites of consecrating the meret-chests and driving the calves (= Egyptologische uitgaven. Volume 8). 2 volumes. Nederlands Institut voor het Nabije Oosten, Leiden 1995, ISBN 90-6258-208-7 (also: Leiden, Univ., Diss., 1993).

- Frank Feder : The ritual "saha-ka-sehnet" as a temple festival of the god Min. In: Rolf Gundlach, Matthias Rochholz (ed.): Festivals in the temple (= Egypt and Old Testament, files of the Egyptological temple conferences. Part 2). 4th Egyptological Temple Conference , Cologne, October 10-12 , 1996. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-447-04067-X , pp. 31-54.

- Frank Feder: Greetings to you, Min-Amun, Lord of the Sehnet Chapel - a hymn on its way through cult history. In: Caris-Beatrice Arnst: Encounters - Ancient Cultures in the Nile Valley. Ceremony for Erika Endesfelder , Karl-Heinz Prize, Walter Friedrich Reineke , Steffen Wenig . Wodtke & Stegbauer, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-934374-02-6 , pp. 111-122.

- Catherine Graindorge : From Min's White Bull to Amenemope: Metamorphoses of a Rite. In: Carola Metzner-Nebelsick (Hrsg.): Rituals in prehistory, antiquity and the present. Studies in Near Eastern, Prehistoric and Classical Archeology, Egyptology, Ancient History, Theology and Religious Studies (= International Archeology. Study Group, Symposium, Conference, Volume 4). Interdisciplinary conference from 1st to 2nd February 2002 at the Free University of Berlin. Leidorf, Rahden 2003, ISBN 3-89646-434-5 , pp. 37-43.

- Rolf Krauss : Sothis and moon dates. Studies on the astronomical and technical chronology of ancient Egypt (= Hildesheimer Egyptological contributions. Volume 20). Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1985, ISBN 3-8067-8086-X .

- Christian Leitz (Hrsg.): Lexicon of the Egyptian gods and names of gods . Volume 3: P - nbw (= Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. Volume 112). Peeters, Leuven et al. 2002, ISBN 90-429-1148-4 , pp. 288-291.

- Herbert Ricke : The Kamutef Shrine Hatshepsut and Thutmoses' III. in Karnak. Report on an excavation in front of the Muttempel district (= contributions to Egyptian building research and antiquity volumes 3 and 2, ZDB -ID 503160-6 ). Swiss Institute for Egyptian Building Research and Antiquity, Cairo 1954.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alexandre Moret , Georges Davy : Des clans aux empires. L'organization sociale chez les primitifs et dans l'Orient ancien (= L'Évolution de l'humanité . Synthèse collective. Section 1, 6). La Renaissance du Livre, Paris 1923, pp. 173-175.

- ^ A. Egberts: In quest of meaning. Leiden 1995, p. 361.