Mummy portrait

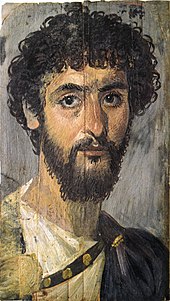

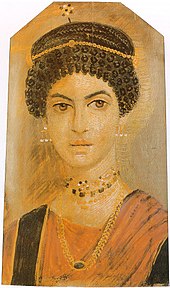

Mummy portrait (also Fayum portrait ) is the modern name for portraits that were wrapped in the mummy wrapping on wooden panels in Egypt or, more rarely, painted on the wrapping of mummies .

Mummy portraits have been found in all parts of Egypt, with a special concentration in the Fajum ( e.g. Hawara ) and in Antinoopolis . They date to the Roman period , although this custom apparently began in the late last BC or early 1st century AD. The end of their production is controversial. Recent research on this question tends towards the middle of the 3rd century.

The mummy portraits mostly show a person in the chest or head portrait in frontal view . The background of the picture is always one color. In their artistic tradition, these sculptures are clearly of Roman origin. Technically, two groups can be distinguished: pictures in encaustic (wax painting) and in tempera , whereby the former are of higher quality on average.

Research history

Today about 900 mummy portraits are known. Most of the images were found in the Fajum necropolis . In many cases, thanks to the Egyptian climate, the pictures are still very well preserved, and even the colors usually look fresh.

For the first time, mummy portraits were discovered and described by the Italian explorer Pietro della Valle in 1615 during his stay in the Saqqara oasis - Memphis . He brought two of the mummies with him to Europe; today they are in the Dresden State Art Collections . After that, interest in ancient Egypt increased over the course of time, but new mummy portraits did not penetrate the consciousness of Europeans again until the beginning of the 19th century. Today it is unclear where the first of these finds came from, possibly again from Saqqara or from Thebes . In 1827, Léon de Laborde brought two portraits allegedly found in Memphis to Europe, one of which is now in the Louvre and the other in the British Museum . The Prussian baron Heinrich Menu von Minutoli acquired several mummy portraits as early as 1820 , but they were lost along with other Egyptian artefacts in 1822 when the "Gottfried" sank on the North Sea. From the expedition that Jean-François Champollion carried out in Egypt in 1828/29, Ippolito Rosellini brought a portrait from an unknown site to Florence that was so similar to the two portraits that Laborde found that they must also have come from Memphis. Through the British Consul General in Egypt, Henry Salt , several pictures reached Paris and London in the 1820s. Some of the people depicted on them were long considered the family of the Theban archon Pollios Soter, who was also known from written sources , but this turned out to be wrong.

As a result, it took a long time before new finds of mummy portraits became known. The first such news from 1887 is initially of a rather fatal nature for science. Daniel Marie Fouquet received information about the discovery of several portrait mummies in a grotto. A few days later he set out to look at them, but came too late as the explorers had burned almost all of the wooden pictures on the three cold desert nights before. He acquired the last two of the 50 or so portraits. It is unclear where they can be found; possibly he was rubayat . A little later, the Viennese art dealer Theodor Graf found more paintings there and tried to exploit these finds as profitably as possible. He won over the well-known Leipzig Egyptologist Georg Ebers to publish his findings. Using presentation folders, he promoted the pieces across Europe. Although not much was known about the context of the find, he went so far as to ascribe the portraits found to known Ptolemaic rulers and their relatives using other works of art, especially coin portraits . None of these assignments were really coherent and conclusive, but they brought him a lot of attention, especially since people like Rudolf Virchow supported these interpretations. All of a sudden, mummy portraits were on everyone's lips. At the end of the 19th century, the portraits became coveted collectibles and were widely distributed through the international art trade because of their very own, special aesthetic.

Scientific research was also advancing. Also in 1887 Flinders Petrie began his excavations in Hawara , where he discovered, among other things, an imperial necropolis from which 81 portrait mummies were recovered in the first year. At an exhibition in London, the portraits became a crowd puller. The following year he successfully continued digging in the same place, but faced competition from a German and an Egyptian art dealer. In the winter of 1910/11, Petrie returned to the site and dug up a further 70 portrait mummies, which, however, were in very poor condition. With a few exceptions, the excavations of Flinders Petrie are the only examples of mummy portraits that have been found in a systematic excavation and the results of which have been published. Although these publications leave many questions unanswered from today's perspective, they are still the most important source for the circumstances of the mummy portraits. In March 1892, the German archaeologist Richard von Kaufmann discovered the so-called grave of Aline , in which some of today's best-known mummy portraits were found. Other important sites were Antinoopolis and Achmim . French archaeologists like Albert Gayet dug in Antinoopolis . As with many other researchers of the time, his methods left much to be desired. His excavation documentation is inadequate and many find contexts can no longer be explored today. On the other hand, as a devotee of occult science , he asked fortune tellers for information about his findings.

Today mummy portraits can be found in almost every major archaeological museum in the world. Due to the often improper salvage, the circumstances of the finds can no longer or only insufficiently be reconstructed, which reduces the cultural-historical-archaeological value. In research, in addition to their cultural and historical value, the research results are in part controversial.

Materials and Manufacturing

Preserved mummy portraits are for the most part painted on wooden panels. There were also mummy portraits that were applied directly to the mummy canvas or the shrouds. The wooden panels were made from high-quality imported hardwoods ( oak , linden , sycamore , cedar , cypress , fig , lemon ) cut into thin, rectangular pieces and then polished. Sometimes the boards were also primed with a plaster mixture. In some pictures, preliminary drawings can be seen. Occasionally, multiple or bilateral use of the wood can also be proven. The pictures were set in a "picture window" in the mummy wrapping.

A distinction must be made between two painting techniques: On the one hand, the encaustic technique, on the other hand, the egg tempera technique . There are also mixed forms or deviations from the common painting techniques. The pictures in encaustic technique appear " impressionistic " due to the juxtaposition of bright and saturated colors , pictures in tempera form, on the other hand, are more subdued because of the delicate gradation of their chalky hues. Sometimes gold leaf was used for the jewelry and wreaths of the sitters. Accentuation and differentiation of light and shadow were related to the localization of the light source. The color of the background was used, especially in early, high-quality portrait examples .

Cultural-historical context

In Ptolemaic times , the burial customs of the Egyptians largely followed old traditions. The corpses of the upper class were mummified , they received a decorated coffin and a mummy mask was placed over the head of the mummy. The Greeks who came to the country followed their own customs. There is ample evidence from Alexandria and other places that the bodies were cremated according to Greek custom. This generally reflects the situation in Hellenistic Egypt, where the rulers pretended to be pharaohs before the Egyptians , but otherwise lived in a completely Hellenistic world that took in only a few indigenous elements. It was not until later that the Ptolemaic pharaohs, such as Cleopatra, were mummified. The Egyptians, on the other hand, only slowly integrated themselves into the Greco-Hellenistic culture, which has dominated almost the entire eastern Mediterranean region since the conquests of Alexander the Great . This changed fundamentally with the arrival of the Romans. Within a few generations, any Egyptian influence disappeared from everyday culture. Cities like Karanis or Oxyrhynchos are largely Greco-Roman places. There are clear indications that a mixture of different ethnic groups had manifested itself within the ruling class of the empire.

The survival of Egyptian forms can only be observed in the field of religion. Egyptian temples were built in the second century. In the funeral culture, Egyptian and Hellenistic elements were mixed. Coffins are becoming increasingly unpopular. Their production stopped completely sometime in the second century. The mummification of corpses, on the other hand, appears to have been practiced in large parts of the population. The Egyptian mummy masks became more and more Greco-Roman in style. Egyptian motifs became increasingly rare. The adoption of Roman portrait painting in the Egyptian cult of the dead must also be seen in this context . These portraits are entirely Roman in their sense of style. In the Roman cult of ancestors, portraits of the ancestors, painted or three-dimensional, played an important role. These ancestral portraits were placed in the atrium of the houses. Greek authors report that in Egypt the mummies were kept indoors for a while. It can therefore be assumed that in the custom of painted mummy images, elements of the Roman ancestral cult were mixed with Egyptian belief in the dead. The portraits known from the Roman ancestor cult, which were placed in the middle of the house, "migrated" to the mummies, which were kept in the house for quite a while. The heads or busts of men, women and children were shown in the pictures. They are in the time of 30 BC. Dated to the 3rd century BC. The portraits seem very individual today. For a long time it was assumed that the pictures were made while the portrayed were still alive and that they were kept in the household as “salon pictures” until death, presented and added to the wrapping of the mummy after death. However, recent research suggests that the pictures were more likely to be painted after death. The multiple use of wood may speak against this; In the case of some pieces, it is even assumed that individual portraits have changed, which was only possible before the burial. The individualization of the portrayed consists only of a few points that were inserted into a given scheme. The custom of depicting the deceased was not new, but the pictures now replaced the earlier Egyptian death masks, which, however, continued to exist and were not infrequently found in the immediate vicinity, even in the same graves as painted portraits.

The commissioners of the pictures apparently belonged to the wealthy upper class of the military, civil servants and religious dignitaries. Not everyone could afford such pictures; many mummies were found without a portrait. Flinders Petrie states that for every 100 mummies he excavated, only one or two mummies with portraits were found. Prices for mummy portraits have not survived, but it can be assumed that the material cost more than the actual wages, since painters were viewed as craftsmen in antiquity and not as artists as they are today. The findings in Aline's grave are also interesting. It contained four mummies: the mummy of Aline, two children and that of her husband. However, her husband was not equipped with a mummy portrait, but had a gold-plated, plastic mummy mask. Plastic mummy masks may have been preferred when the financial means allowed. It is unclear whether the portrayed were of Egyptian, Greek or Roman origin or whether this form of representation was common among all ethnic groups . Some names of those portrayed are known in writing; there are names of Egyptian, Macedonian, Greek and Roman origins. Hairstyles and clothing were always based on Roman fashion. Women and girls were often depicted with precious jewelry and in splendid robes, men often in special costumes. Greek inscriptions are relatively common, and occupational titles are rarely found. The portrait of Eirene is the only mummy portrait to show an inscription in hieratic script . It is unclear whether these inscriptions always reflected reality or just played an ideal that did not correspond to actual living conditions. A single inscription clearly indicates the occupation of the sitter, a shipowner . The mummy of a woman named Hermione had grammatike as an inscription next to the name . For a long time it was assumed that Hermione was a teacher, and Flinders Petrie gave the supposed teacher to Girton College in Cambridge , an educational institution. Nowadays, however, it is assumed that the inscription indicated the level of education of the deceased. Some of the men shown were shown with sword belts or even with sword pommel, which suggests that they belonged to the Roman military.

The religious meaning of the mummy portraits, as well as the associated funeral rites, has not been adequately explored. However, there are signs that the custom developed from genuine Egyptian rites that were adapted by a multicultural upper class. The custom of mummy portraits was widespread from the Nile Delta to Nubia , as can be proven by finds. It is noticeable that, apart from the sites in the Fajum (especially in Hawara and Achmim) and in Antinoopolis, other forms of burial were predominant. At the same time, different forms of burial existed side by side at many sites. The grave types were not least dependent on the status and financial possibilities of the client. There are also local traditions and customs. Portrait mummies were found in rock graves and free-standing grave complexes, but also in small pits just below the surface. It is noticeable that almost all of these burials lack grave goods, apart from a few gifts in the form of pottery and plant containers.

For a long time it was assumed that the latest portraits must be dated to the end of the 4th century; In recent years, however, it has become more and more assumed that the last panel portraits are in the middle, the last painted shrouds in the second half of the 3rd century. It is generally believed that production has declined sharply since the beginning of the 3rd century. There are several reasons for the end of the mummy portraits in discussion, which, however, cannot be viewed in isolation from one another, but rather worked together: On the one hand, the Roman Empire was in a severe economic crisis in the 3rd century, which also affected the financial possibilities of the upper class Took influence. Although she continued to spend a lot of money on representation purposes, she shifted more and more to public appearances, for example at parties or games, and no longer so much to the production of portraits. However, other areas of sepulchral culture , such as sarcophagus production, remained at a high level.

In any case, a religious crisis is recognizable, which had only limited to do with Christianity, as was long assumed, especially since the last images were dated to the time of the final victory of Christianity . Christianity still explicitly allowed mummification in later times, so it could not be the reason for the end of portrait painting. However, a neglect of the Egyptian temples in the course of the advancing Roman Empire can be shown. Interest in Egyptian and ancient cults decreased massively at the latest by the 3rd century. With the Constitutio Antoniniana , the granting of Roman citizenship to all free persons, the social structure shifted. In addition, the Egyptian cities were allowed self-administration for the first time since they became part of the Roman Empire . Now the provincial upper class and their relationship to one another changed. It is probable that all factors interacted that led to a change in rites and probably also in fashion. A clear statement about the end of the mummy portraits cannot, however, be made based on current knowledge.

It is possible that new discoveries will show a different picture of burial forms in the coming years. There are suspicions that the center of mummy portrait production - and thus also the center of this form of burial - was in Alexandria. Recent discoveries in Marina el-Alamein make this assumption appear more and more realistic. Today, mummy portraits are considered to be one of the few examples of ancient art that can be used as a substitute for "large" paintings that have not been preserved - and especially Roman portrait painting - and give an impression of the painting of Greco-Roman antiquity.

Hairstyles, clothes and jewelry

Various hairstyles can be found on mummy portraits. They represent one of the most important dating aids. For the most part, the deceased are depicted with the fashionable hairstyles of their time. There are many analogies to the hairstyles of sculptures . When they showed members of the imperial family, they were often displayed publicly throughout the empire as a means of propaganda. As a result, fashions that were often initiated by members of the imperial family also spread. Nevertheless, it seems that fashions in the provinces, as can be seen from the mummy portraits, often lasted longer than, for example, at the imperial court, at least several possibilities existed side by side. Naturally, it is easier to observe fashion trends in female hairstyles. Men generally wore a short hairstyle. For women, a rough chronological sequence can be traced: from simple middle parting hairstyles in the Tiberian period to more pronounced forms of ringlet curls, pigtail hairstyles and curly toupees over the forehead in the late 1st century, smaller oval pigtailed nests in the early Cantonese period , simple middle parting hairstyles with neck knots in the second half of the 2nd century, wig-like, puffy and straight, strict hairstyles in the Severian era up to braid loops on the head, which were in fashion in the late phase of mummy portraits and were only found on a few shrouds. It seems that curly hairstyles in particular were very popular in Egypt.

Like the hairstyles, the clothing also corresponds to the general fashions in the Roman Empire, as they are also known from statues and busts. Both men and women usually wear a thin chiton as an undergarment. Over it, a coat is usually worn by both sexes, which is placed over the shoulders or wrapped around the upper body. For men, both pieces of clothing are almost exclusively white, while women often wear red and pink tones, but also yellow, green, white, blue and purple. The chitons always have a decorative stripe ( clavus ) in light red or light green, sometimes also in gold, but mostly in dark shades. On shrouds from Antinoopolis are robes with long sleeves and very wide clavi. So far not even a clearly represented toga , after all a symbol of the Roman citizen, has been found. Rather, Greek cloaks and togas cannot be distinguished on representations in the first century and in the first half of the second century due to the similar draping. Since a toga was never depicted on the full-length shrouds either, it can be assumed that it was not part of the pictorial program. In the late 2nd century, the way of draping changes. Now the depiction of clothing is developing into the Togagewall typical of the third century in particular. These weren't real togas, however.

With a few exceptions, jewelry is only found in women. It also corresponds to the common types of jewelry of the Greco-Roman East. Simple gold link chains and massive gold bracelets can be found especially in pictures from Antinoopolis. There are also depictions of precious and semi-precious stones such as emeralds , carnelians , garnets , agate or amethysts , and more rarely pearls. Most of the time, the stones were cut into cylindrical or round pearls. Sometimes there are magnificent necklaces that show the gemstones set in gold.

There are three basic forms of earrings: Firstly, there are round or teardrop-shaped pendants that were widespread, especially in the 1st century, which (if one consults real archaeological finds) were probably spherical or hemispherical. In later times the taste changed to S-shaped bent hooks made of gold wire, on which up to five pearls made of different materials and in different colors were drawn. The third form is more elaborate pendants, with two or three, sometimes even four, vertical rods hanging from a horizontal bunny, most of which are decorated with a white pearl at the bottom. Often there are golden hairpins adorned with pearls, dainty tiaras or, especially in Antinoopolis, golden hairnets. In addition, amulets and pendants are shown in many pictures , which most likely had a magical function.

Art historical significance

The mummy portraits are of particular importance in terms of art history. It is known from ancient sources that panel painting (as a genre in contrast to wall painting ), i.e. the painted picture on wood or another movable painting surface, was of great importance. However, very few works of this panel painting have survived, such as the Septimius Severus Tondo , a framed portrait from Hawara or the picture of a man flanked by two deities.

The mummy portraits show elements of icon painting with their focus on the essentials and frontality of the representation . A direct connection has occasionally been made here. They represent only a very small percentage of the ancient portrait painting that once existed. In their entirety, they probably had an influence on icon painting in the Byzantine period .

literature

- WM Flinders Petrie : Roman Portraits and Memphis IV. London 1911 (Petrie's excavation publication, online ).

- Klaus Parlasca : Mummy portraits and related monuments. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1966.

- Klaus Parlasca: Ritratti di mummie, Repertorio d'arte dell'Egitto greco-romano. Volume B, 1-4, Rome 1969-2003 (corpus of all known mummy portraits).

- Henning Wrede : Mummy portraits . In: Lexicon of Egyptology . Vol. IV, Wiesbaden 1982, columns 218-222.

- Barbara Borg : Mummy Portraits. Chronology and cultural context. von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1742-5 .

- Susan Walker, Morris Bierbrier: Ancient Faces, Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt. British Museum Press, London 1997, ISBN 0-7141-0989-4 .

- Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies (= Zabern's illustrated books on archeology . / Special issues of the ancient world ). von Zabern, Mainz 1998, ISBN 3-8053-2264-X ; ISBN 3-8053-2263-1 .

- Wilfried Seipel (Ed.): Pictures from the desert sand. Mummy portraits from the Egyptian Museum Cairo; an exhibition at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, October 20, 1998 to January 24, 1999. Skira, Milan 1998, ISBN 88-8118-459-1 .

- Klaus Parlasca; Hellmut Seemann (Ed.): Moments. Mummy portraits and Egyptian funerary art from Roman times [to the exhibition Moments - Mummy portraits and Egyptian funerary art from Roman times, in the Schirn-Kunsthalle Frankfurt (January 30th to April 11th, 1999)]. Klinkhardt & Biermann, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-7814-0423-4 .

- Nicola Hoesch: Mummy portraits. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , column 464 f. (Comment).

- Paula Modersohn-Becker and the Egyptian mummy portraits… Catalog book for the exhibition in Bremen, Art Collection Böttcherstraße, October 14, 2007–24. 2. 2008. Hirmer, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-7774-3735-4 .

- Jan Picton, Stephen Quirke, Paul C. Roberts (Eds.): Living Images, Egyptian Funerary Portraits in the Petrie Museum. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek CA 2007, ISBN 978-1-59874-251-0 .

- Stefan Lehmann : Mummies with portraits. Evidence of the private cult of the dead and belief in gods in Egypt during the imperial era and late antiquity. In: John Scheid , Jörg Rüpke (eds.): Funéraires et culte des morts. Colloquium at the Collège de France, Paris 1st – 3rd March 2007. Steiner, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-515-09190-9 , pp. 135-152.

Web links

- Mummy portrait in the large art dictionary by PW Hartmann

- The mummy portraits in the Petrie Museum (one of the largest collections of these works outside of Egypt)

- Mummy portrait of the Munich antique collections - high-resolution digital version in the culture portal bavarikon

Individual evidence

- ↑ Corpus of all known copies: Klaus Parlasca: Ritratti di mummie , Repertorio d'arte dell'Egitto greco-romano Vol. B, 1-4, Rome 1969–2003; Another copy that has since emerged: Petrie Museum UC 79360, BT Trope, S. Quirke, P. Lacovara: Excavating Egypt , Atlanta 2005, p. 101, ISBN 1-928917-06-2

- ↑ a b c d Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, p. 10 f.

- ↑ a b Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, pp. 13 f., 34 ff.

- ^ Petrie: Roman Portraits and Memphis IV. P. 1.

- ↑ German Archaeological Institute (ed.): Ancient monuments. Volume 2. Berlin. 1908. ( digitized version )

- ↑ a b c d e f g Nicola Hoesch: Mummy portraits. In: The New Pauly . Vol. 8 (2000), p. 464.

- ^ Wrede, LÄ IV, 218

- ↑ Such pictures are possibly indications that the pictures were made during the lifetime of the depicted

- ↑ Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, pp. 40–56; Walker, Bierbrier: Ancient Faces , pp. 17-20

- ↑ in summary: Judith A. Corbelli: The Art of Death in Graeco-Roman Egypt , Princes Risborough 2006 ISBN 0-7478-0647-0

- ↑ Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, p. 78

- ^ Nicola Hoesch: Mummy portraits in: Der Neue Pauly , Vol. 8 (2000), p. 464; other researchers such as Barbara Borg assume that mummy portraits began in Tiberian times.

- ↑ a b Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, p. 58

- ^ Nicola Hoesch: Mummy portraits in: Der Neue Pauly , Vol. 8 (2000), p. 465

- ↑ Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, pp. 53–55

- ↑ Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, p. 31

- ↑ Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, pp. 88–101

- ↑ Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, pp. 45–49.

- ↑ Barbara Borg: "The most delicate sight in the world ...". Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, pp. 49–51

- ↑ Barbara Borg: “The most delicate sight in the world…” Egyptian portrait mummies , Mainz 1998, pp. 51–52

- ^ Susan Walker, Morris Bierbrier: Ancient Faces, Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt . London 1997, pp. 121-122, no. 117

- ^ Susan Walker, Morris Bierbrier: Ancient Faces, Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt . London 1997, pp. 123-124, No. 119