New York, Westchester and Boston Railway

| New York, Westchester & Boston Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The New York, Westchester and Boston Railway (abbreviated NYWB or NYW & B , called Westchester or Boston – Westchester ) was a standard-gauge, electrified high-speed railway that spanned the southern tip of the Bronx in New York City with some cities and towns in Westchester County in the US state of New York linked. It belonged to the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad (NYNH & H, called New Haven ) group of companies and was in operation from 1912 to 1937.

Most of the Westchester was built parallel to the existing New Haven lines to relieve them of local traffic. In addition, it had comparatively very spacious, ultra-modern and correspondingly expensive operating facilities and was therefore designed for very high transport services. Since the Westchester was built through largely sparsely populated areas, a corresponding demand never arose, so that the bankruptcy of the New Haven group of companies in the course of the global economic crisis finally meant the end of the railroad lines.

Most of the routes were dismantled in the years immediately after the closure. A smaller portion was taken over by the New York subway and is still in operation today.

prehistory

Railways in northern New York

In the mid-19th century, there were several rail lines running north from New York City east of the Hudson River . Seen from west to east, these were the Hudson River Railroad to Albany and Troy , the New York and Putnam Railroad to Brewster and the New York and Harlem Railroad to Chatham . From 1869, all three routes belonged to the newly formed New York Central and Hudson River Railroad , or New York Central for short , and ended at Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan from 1871 .

Since 1849 the tracks of the competing New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad , or NYNH & H or New Haven for short , ran further east . They branched off at Woodlawn from the New York and Harlem Railroad, crossed the New York - Connecticut state line at Port Chester and continued via Bridgeport to New Haven . In addition, a branch line was added in 1873 with the Harlem River Branch; the tracks of the previously independent Harlem River and Port Chester Railroad led from New Rochelle in a southerly direction down to the Harlem River (132nd Street).

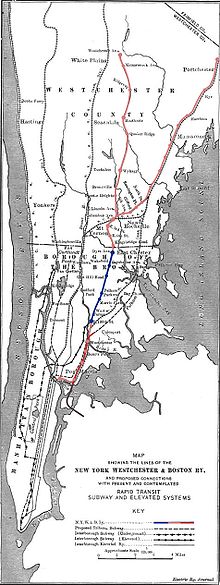

The New York, Westchester and Boston Railway Company was founded on March 20, 1872 to build another railroad between the existing lines from the then New York city limits on the Harlem River through Westchester County . The route was to run from the Harlem River through the eastern Bronx , then to Mount Vernon and on through the southeastern part of the county to Port Chester. The concession also included two branches, one from 177th Street, Bronx, east to Throgs Neck , and another from Mount Vernon north across White Plains to Elmsford . The tracks were to run in parts parallel and thus in competition with the two lines of the New Haven. However, the founders' crash of 1873 put an end to the company before construction began.

The New Haven is buying

In 1906, William Rockefeller and JP Morgan bought NYW & B for $ 11,000,000 and then transferred it to New Haven.

This excessive amount of money was due to the business practices of New Haven at the time. These consisted of buying up, consolidating and technically modernizing all local competitors practically at any price. By 1912, this had created a transport network with over 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of railways, as well as other tram and steamship lines in southern New England . This de facto monopoly in the transport industry was under the control of JP Morgan and his confidante on the board of New Haven, Charles Sanger Mellen .

In addition, New Haven hoped that the purchase and subsequent construction of NYW & B would have positive financial effects, because the route to Port Chester was heavily overloaded by the many local trains to and from New York City. This was primarily at the expense of profitable long-distance and freight traffic, so that an increase in transport capacities along this route seemed sensible. In addition, the New Haven was obliged by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to offer the tickets for local transport connections to and from New York City at a standard fare of 5 US cents. However, the trains in question had to use the route of the competing New York Central south of Woodlawn due to the lack of their own tracks, which in turn required a route fee of 24 cents per passenger for the journey to Grand Central station. In order to end the constant losses of 19 cents per passenger, the local trains should in future run over the NYW & B route to the Harlem River to allow passengers to transfer to the elevated train.

Likewise, these considerations were made in anticipation of further expansion of New York City's main business district to the north. Until around 1850 this had developed mainly in the area of today's Financial District south of Canal Street and reached Midtown Manhattan around 1900 . It was generally assumed that the district of Harlem and the southern Bronx would experience a similar development by around 1950 in view of the recently opened subway, so that the new transport connection would become increasingly important. For the rural Westchester County itself, there were high hopes for a rapidly growing traffic volume. Between 1900 and 1910 the population had increased by over 70%, and the price of land had tripled at times.

construction

The originally planned branches to Throgs Neck and via White Plains to Elmsford were basically of no interest for the project to build a new line for local traffic parallel to the existing lines of the New Haven. An application was made to the responsible New York Public Service Commission to remove these routes from the concession. There only the elimination of the branch line to Throgs Neck was approved; the route to Elmsford could only be withdrawn as far as White Plains.

Construction work on the line began in May 1909. The first section from 180th Street station to North Avenue in New Rochelle was opened on May 29, 1912. From July 1 of the same year, it continued to the terminus Westchester Avenue in White Plains. The Harlem River Terminal was reached on August 3, 1912.

The entire route was very complex. The line consisted of two tracks and even had four tracks south of Mount Vernon. Wide curve radii and low gradients allowed a high expansion speed . This required massive site developments and dozens of engineering structures. Right from the start, the entire length of the line was electrified by means of an overhead line to enable continuous electrical operation.

The train stations and stops were just as lavishly and generously designed, with particular emphasis on aesthetics . The buildings and thus the railway as a whole should look as attractive as possible in order not to negatively influence the price of land and thus promote settlement development along the railway line. So the buildings were made of stone and often in the neo-renaissance style ; shops were set up inside and the outside areas laid out. The equipment also included terrazzo floors and central heating .

In addition, there was a fleet of comfortably equipped electric multiple units , each with an output of 350 hp and a top speed of 57 mph (92 km / h). The Westchester represented the state of the art of a rapid transit system at the time and was designed for very high capacities. The total cost of building the railroad and purchasing the vehicles officially came to $ 22 million.

The actual goal of reducing the loss-making number of passengers along the original route from New Haven to New York City required the completion of the new parallel line to Port Chester. Construction across North Avenue began in 1921; Mamaroneck was reached in 1926, Harrison in 1927, Rye in 1928 and Port Chester in 1929. The number of passengers in local traffic then fell on the existing routes, and so this could be set along the Harlem River Branch on July 27, 1930.

The route extension from North Avenue to Port Chester was apparently built to simpler standards for financial reasons. Two main tracks were laid here, too, but the platforms were only made of wood, and instead of large buildings there were only small wooden houses as access systems.

Route

Harlem River - 180th Street - Columbus Avenue

The route began on the north bank of the Harlem River at the Harlem River Terminal corner of 132nd Street and Willis Avenue. There was a direct rail connection to the IRT Third Avenue Line and a covered wooden pedestrian bridge over to its 133rd Street station . Of the total of six parallel platform tracks, two were used by NYW & B and four by the elevated railway.

The route first ran along the bank in a southeast direction and then flowed into the Harlem River Branch of New Haven. After four intermediate stops, the route branched off again at 174th Street, swiveled to the northwest and reached the subway at 180th Street with the IRT White Plains Road Line . Behind it it went northeast to the city limits and beyond that further north along South Fulton Avenue through Mount Vernon to Columbus Avenue station . By then there were five more stops on the New York side and three in Mount Vernon. The second station behind 180th Street , Pelham Parkway , was in the tunnel.

The New Haven railway line was crossed at Columbus Avenue ; the station was set up as a tower train station with corresponding transfer options. About half a kilometer to the northeast, the four-track line finally forked.

Columbus Avenue – Westchester Avenue

From Columbus Avenue one stretch continued north towards White Plains. It was consistently two-pronged and had a total of nine other stations in Mount Vernon, Eastchester , New Rochelle, Scarsdale and White Plains. The terminus White Plains – Westchester Avenue was the corner of Westchester Avenue and Bloomingdale Road immediately east of the city center.

Columbus Avenue – Port Chester

The other branch line was also continuously double-tracked and initially ran east and served two more stations each in Pelham and New Rochelle, before meeting the New Haven for the second time just after what is now New Rochelle station . There the route swiveled to the northeast and ran parallel to New Haven to Port Chester station just before the New York – Connecticut state border. Along this section, the Westchester not only served all stations of the New Haven, but also a few additional stops. In contrast to the Harlem River Branch, it had its own tracks throughout.

business

Westchester's operating facilities were designed so that, in addition to local trains (strollers) that stopped everywhere, express trains that did not stop at every station could also be offered. While the two-track sections north of Columbus Avenue were used by both train groups in mixed operation, the outer pair of tracks on the four-track section served the locals and the inner track was used by the express trains for overtaking in the same direction . The stations along this route were aligned to this operating scheme, so that at conventional stations only side platforms existed on the outer pair of tracks, while express stations had two central platforms between the directional tracks. Express stations were in particular 180th Street , Pelham Parkway and East 3rd Street on the four-track section and Wykagyl and Heathcote on the route to White Plains. In the direction of Port Chester , the assignment changed as construction progressed.

Westchester was required by concession to offer at least 60 pairs of local trains with a maximum interval of 30 minutes between 4:00 a.m. and 1:00 a.m. in Mount Vernon there had to be at least 50 pairs of trains to and from New York City. According to the will of NYW & B, the associated express trains should also run with a time delay of half, which in turn should be timed so that it was possible to change trains on East 3rd Street in the direction of travel. The travel time between 180th Street and White Plains was 25 minutes by local 39 and by express train. In the direction of New Rochelle (North Avenue) it took 25 minutes with the local and 13 minutes with the express.

Operations began in 1912 with 20-minute intervals for locals and 40-minute intervals for express trains. It should be compressed further to 15/15 minutes later. Overall, the route was designed to allow local and express trains to run in extreme cases every five minutes in each direction and thus to almost reach the level of the New York subway.

The end

Westchester was a high-loss company from the start. The cause of losses of more than 3 million dollars a year in recent times was not only due to the dimensioning of the operating systems and the associated fixed costs . The number of passengers also never reached the originally targeted level because the assumptions regarding population growth in the region had been far too optimistic. Although the number of passengers rose steadily over the years, from 2,874,484 (1913) to 6,283,325 (1920) and finally 14,053,188 in 1928, the Westchester did not get more than 264 trains a day by 1930, which meant the line capacity was far from being exhausted.

In addition, both New York Central and New Haven offered commuter trains to New York City on their parallel routes, which, unlike Westchester, went directly to Grand Central Terminal in the city center. In addition, unlike other railway companies, NYW & B could not rely on profitable freight traffic.

As long as Westchester did not break even , New Haven had to bear the deficit and on top of that the interest burden and the loan guarantee. NYW & B was thus fully dependent on the financial health of its parent company.

This, in turn, has always seemed to be a very healthy company. But Mellen had built a pyramid system from the 336 subsidiaries of New Haven , the profits of which were mainly achieved by falsifying accounts. Although these facts had come to light as early as 1913, the financial troubles of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railway apparently did not seem to have ended. The global economic crisis led to bankruptcy in October 1935. Westchester then fell into arrears due to the lack of support payments and followed around a month later on November 30th. By then it had amassed a total deficit of $ 45,000,000.

First, an attempt was made to keep the railway alive through cost-cutting measures and simultaneous efforts to increase the number of passengers. However, because there was no improvement in the course of the next two years in view of the high costs for interest, lease and property tax, operations were initially discontinued by a court order. The last train to Port Chester ran on October 31, the last between the Harlem River Terminal and White Plains on December 31, 1937. After attempts to sell the company to an investor or to bring it under state control, failed which Westchester finally liquidated by court order .

The city of New York acquired the section between 174th Street and the city limits behind the Dyre Avenue station for 1.7 million dollars in order to integrate it into its subway network . The electric railcars stayed with the New Haven; they were converted to non-motorized passenger cars and used in suburban trains in the Boston area. The remaining fixed assets were auctioned in March 1942 and brought in $ 423,000; Rails and overhead lines were dismantled and then used in the armaments industry for war use. Many of the station buildings were left to the responsible municipalities to compensate for the tax debts.

Technical details

The New York, Westchester and Boston Railway was designed as a largely independently operated rapid transit system and built through sparsely populated areas in many places. In addition, the routing did not have to align with existing, slower-to-travel railway lines. In this respect, almost no compromises were necessary in terms of routing, concession or technical equipment, so that the railway represented what was technically feasible at the time.

Route

The route should be laid out for as high an expansion speed as possible , which should be achieved by low inclines (maximum 1%) and gentle curves (maximum 4 degrees). Level crossings should also be consciously avoided. To make this possible in the partly hilly terrain, generous cuttings, viaducts and dams had to be created along the route. In addition, there were over 70 engineering structures, namely a 0.75 mile (1.2 km) long, four-track tunnel with an underground station under the Pelham Parkway in the Bronx, several viaducts and a few dozen bridges and underpasses. All of these buildings were extremely massive; even pedestrian walkways, insignificant in themselves, were made of steel.

Graveled sleeper tracks were laid throughout the route. This was also done on bridges and viaducts in order to keep the noise level as low as possible, for which purpose concrete troughs were placed on the structure. The cant in the curves has also been precisely optimized for the driving speeds expected there. The train protection was carried out by means of automatic block signals.

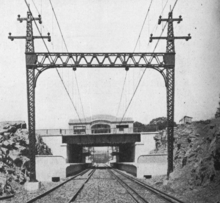

power supply

New Haven's 25 Hz, 11 kV AC system was used for power. The overhead line was suspended from portal lattice masts and had two support cables arranged one above the other (compound catenary) . The upper suspension ropes were suspended from the upper edges of the trusses and remained without power. In the middle of the 300-foot (91.44 m) long fields, the lower suspension cables were suspended by means of insulators and connected to each other with transverse rods. In particular, the lower suspension cables were not attached to the masts. So that the overhead line could follow the course of the tracks in curves, the supporting ropes were additionally tensioned laterally at these points. In addition, additional cross wires were attached to guide the pantographs within the switch corner.

Another, "experimental" (experimental) type of overhead contact line was used for experimental purposes from Columbus Avenue in the direction of New Rochelle . This single catenary was equipped with only one suspension cable that was hung directly on the underside of the portal mast. This construction, which is more conventional from today's point of view, should ultimately prevail within the NYNH & H group of companies.

Stations

The stations were designed by the architects Reed & Stem , New York and designed according to the aspects of aesthetics, durability and ease of maintenance. The reception buildings were made of concrete and were built in the style of historicism , namely Mission Revival , in the style of neo-renaissance and neoclassicism . In their interior, shops and offices were often set up in addition to the ticket offices; Terrazzo was used for floors and wall coverings . Since the tracks often came to rest in the cut or on a dam, the station buildings were often not at the same height, but below, above or to the side above the route, whereby one of the outer walls was usually flush with the retaining wall of the site development.

The platforms were designed as elevated platforms and, like the station buildings, were made of concrete instead of the wood that was customary at the time. The rear boundary wall, stairs and the Doric columns for the platform roof were also made of concrete. Only the front edge of the platform was designed as a wooden plank in order to be able to widen the clearance profile a little if necessary.

Rolling material

The fleet consisted of 95 four-axle solo multiple units delivered by Pressed Steel Car and Osgood-Bradley between 1912 and 1929. They each had two traction motors with 175 hp each ( axle formula Bo'2 '), could accelerate at up to 1 mph / s (0.447 m / s²) and were limited to a top speed of 57 mph (92 km / h). The wagons also had dead man and follow-up controls ; the power consumption took place via two pantographs , which were arranged above the bogies.

The railcars were 70 feet 4 inches (21.44 m) long, 9 feet 7 3/4 inches (2.94 m) wide, 13 feet 3 1/4 inches (4.04 m) high, and 120,000 pounds (54, 43 tons). Depending on the year of construction, they offered 78 to 80 seats, had large windows and thermostat-controlled heating.

The entire car body consisted of a steel frame with riveted and partially already welded steel plates. The cars were painted in New Haven Green and had transitions with bellows at the front and two characteristic round windows with a diameter of 20 inches (51 cm) at head height. The two driver's cabs were arranged on the right-hand side as seen in the direction of travel. Three compressed air-operated pocket sliding doors with central control were installed on each side; two at the ends and one in the middle. Since the Westchester operated on the Harlem River Branch in mixed operation with conventional trains and there were only low platforms, the two door openings at the vehicle ends were also equipped with steps.

In addition to the railcars, there were also four flat cars , a boxcar , a four-axle electric locomotive and a petrol-electric contact line assembly car for maintenance work.

Depot

The depot was located north of 180th Street station immediately east of the railway line and included a building yard and workshop. This in turn consisted of a 49 feet (14.94 m) wide, 171 feet (52.12 m) long, three-tier hall in steel frame construction and was designed solely for the maintenance and repair of these railcars. Great emphasis was placed on being able to carry out all repairs as quickly and as quickly as possible. The building had large windows for bright rooms and, with its compact external dimensions, was designed for maximum use of space.

Tariff and tickets

Fares were after (at the beginning) a total of eight zones (zones) staggered, wherein the rate was 5 cents for a single trip per zone. Each zone represented a certain section of the route, the boundaries of which were not based on actual distances, but on the municipal boundaries. The 8.39 mile (13.5 km) drive from the Harlem River Terminal to Dyre Avenue within New York cost 5 cents as well as the 1.65 miles (2.66 km) from Kingsbridge Road to Columbus Avenue within Mount Vernons. This zone system differed just as much from the flat-rate tariffs for inner-city transport at the time as well as from the kilometer-based tariffs that were common with conventional railways. The idea for this came from London and Berlin . In addition to their European models, the tickets were marked in a different color depending on the destination zone, for example in red for the New York City area.

At the starting point, passengers bought a ticket to the desired destination zone. This destination zone determined the color and the starting point determined the fare to be paid. The cards were then canceled with a stamp when entering the station at a turnstile and handed over to another turnstile and destroyed when leaving the destination station. The color marking made it easier to check because at each station in a certain zone only tickets in the exact color of this zone were to be handed in. In addition, no train conductors were necessary.

Traces and remains

The section between 180th Street and the city limits today forms the IRT Dyre Avenue Line of the New York City Subway and is served by Line 5. The 4.5 mile (7.24 km) long section was converted to power rail after the sale and finally opened on May 15, 1941 as a shuttle service and on May 6, 1957.

As of 2008, exactly the five original stations are in operation along the route between Morris Park and Dyre Avenue . On 180th Street, the trains no longer go to the original NYW & B station, but thread a little further north into the IRT White Plains Road Line and use the IRT station of the same name . The Westchester station building and the associated platforms including roofing have been preserved and are used as a depot. Overall, the Dyre Avenue Line looks like a normal subway route on the outskirts of New York, apart from the comparatively spacious reception building and the greater distance between stations.

South of 180th Street , the viaduct down to the Harlem River Branch and the track connection at the Harlem River Terminal to the IRT Third Avenue Line remained, because otherwise there would have been no track connection for the transfer of rolling stock. After the opening of the connecting curve to the White Plains Road Line, this makeshift solution became superfluous and dismantled over time. The reception building at the Harlem River Terminal remained until 2006.

Local traffic along the Harlem River Branch was not resumed after the end of NYW & B either on the part of New Haven, so the stations there were abandoned. As part of the north-east corridor , however, the line still plays an important role in long-distance traffic.

North of the New York city limits, the route has often been built over with factories and houses, especially in the Mount Vernon and New Rochelle area, so that it can only be seen in sections on aerial photographs. Further north, however, the railway embankment stands out structurally from the rest of the landscape, particularly due to the land development and its wide curve radii. In some places there are still individual culverts and bridge abutments, such as on Columbus Avenue . The course of the tracks north of New Rochelle and on the Harlem River Branch in the Bronx can be traced through the wider portal masts of the overhead line and individual bridge elements that are still present. Most of the station buildings were either sold and converted, abandoned to decay or demolished over time, provided that no other use was available.

The route between Mount Vernon and White Plains is partly used for other purposes; the cut in the Heathcote area serves as a subgrade for a bypass road and north of it as a hiking trail. The Westchester Mall now stands on the site of the terminus in White Plains .

Additional information

Books

- Arcara, Roger: Westchester's forgotten railway, 1912-1937; the story of a short-lived short line which was at once America's finest railway and its poorest: the New York, Westchester & Boston Railway , expanded and revised edition. Quadrant Press, New York 1972. (English)

- Bang, Robert A .: The New York, Westchester & Boston Railway Company 1906-1946 . Self-published, Port Chester 2004. ISBN 978-0-9762797-1-6 . (English)

- Bang, Robert A., John E. Frank, George W. Kowanski, and Otto M. Vondrak: Forgotten railroads through Westchester County . Self-published, Port Chester 2007. ISBN 978-0-9762797-3-0 . (English)

- Harwood, Herbert H .: The New York, Westchester & Boston Railway: JP Morgan's Magnificent Mistake . Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2008. ISBN 978-0-253-35143-2 . (English)

Magazine articles

Beginning in 1912, a number of articles appeared in the Electric Railway Journal . Two of them offer a good overview:

- McGraw Publishing Company (Eds.): The New York, Westchester & Boston Railway . In: Electric Railway Journal, Volume XXXIX, No. 21, May 25, 1912, pp. 864 ff. (English)

- McGraw Publishing Company (Eds.): Track and Stations of the New York, Westchester & Boston Railway . In: Electric Railway Journal, Volume XXXIX, No. 23, June 8, 1912, pp. 956 ff. (English)

- Herbert H. Harwood Jr .: Grass grows on the Westchester . In: Trains . Kalmbach Publishing Co., October 1951, ISSN 0041-0934 , p. 42-47 .

Web links

- New York, Westchester, & Boston Railway on nycsubway.org (private site, contains contemporary and current photos as well as the mentioned articles from the Electric Railway Journal, but only textually complete; in particular, a number of images and most of the technical drawings are missing; English)

- Bryk, William: The (Rail) Road of Hubris ( Memento October 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) . In: New York Press, News & Columns. (English)

- Otto M. Vondrak: The New York Westchester & Boston Railway Co. , 2007. (private page, English)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Whittemore, Henry: Fullfilment of the Remarkable Prophecies Relating to the Development of Railroad Transportation ( Memento of August 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) , 1909. (Sections on BOSTON AND ALBANY RAILROAD, HUDSON RIVER RAILROAD and NEW YORK AND NEW HAVEN RAILROAD)

- ↑ Christopher T. Baer: PRR CHRONOLOGY: 1873 - February 2005 Edition ( Memento from July 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 103 kB) , 2005. P. 41.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h McGraw Publishing Company (ed.): The New York, Westchester & Boston Railway . In: Electric Railway Journal, Volume XXXIX, No. 21, May 25, 1912, pp. 864 ff.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Bryk, William: The (Rail) Road of Hubris . In: New York Press, News & Columns.

- ↑ The station 133rd Street in the Bronx was intended as a transfer point . See also map Interborough Rapid Transit Co. - 1904 .

- ↑ Clifton Hood: 722 Miles , centennial edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2004, ISBN 0-8018-8054-8 . P. 108 ff.

- ↑ PLANS OF CENTRAL'S RIVAL .; New Haven Road's Subsidiary Line to Begin Building at Once. In: The New York Times. May 2, 1909, p.

- ↑ WESTCHESTER LINE A 'ROAD BEAUTIFUL'; Inspection Trip Shows a Railway Built on a Public-Be-Pleased Plan. In: The New York Times. May 21, 1912, p. 9.

- ^ NEW TRANSIT LINE TO WHITE PLAINS; To be Opened To-morrow by the New York, Westchester & Boston Railway. In: The New York Times. June 30, 1912, Section: Bronx Real Estate Business Financial, p. XX5.

- ↑ Christopher T. Baer: PRR CHRONOLOGY: 1912 - March 2005 Edition ( Memento of October 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 46 kB) , p. 11.

- ^ Gilbert O. Browne: Construction of the New York, New Haven & Hartford New High Speed Electric Line Running North from New York City. In: Railway Age Gazette. June 7, 1912.

- ↑ a b c d e McGraw Publishing Company (ed.): Track and Stations ( Memento June 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Track and Stations of the New York, Westchester & Boston Railway. In: Electric Railway Journal. Volume XXXIX, No. 23, June 8, 1912, pp. 956 ff.

- ^ A b c d e f g h Robert A. Bang, Otto M. Vondrak: NYW & B - History of the New York Westchester & Boston Railway

- ↑ Christopher T. Baer: PRR CHRONOLOGY: 1930 - August 2004 Edition ( Memento from October 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 84 kB) , p. 24.

- ↑ The colors used correspond to the color scheme of the railway line template .

- ↑ WEST CHESTER FIGHT ON TRAINS HALTED In: The New York Times. August 28, 1930, p. 5.

- ↑ NEW HAVEN FILES UNDER SECTION 77 In: The New York Times. October 24, 1935, p. 31.

- ↑ a b SUBURBAN RAILWAY Invokes SECTION 77 In: The New York Times. December 1, 1935, p. F1.

- ↑ WESTCHESTER LINE TO HALT TOMORROW In: The New York Times. October 30, 1937, p. 21.

- ↑ WESTCHESTER LINE PASSES WITH 1937 In: The New York Times. January 1, 1938, p. 36.

- ↑ a b Vondrak, Otto M .: NYW & B - Roster

- ^ McGraw Publishing Company (eds.): The Signal System of the New York, Westchester & Boston Railway . In: Electric Railway Journal, Volume XL, No. 3, July 20, 1912, pp. 80 ff.

- ^ McGraw Publishing Company (eds.): Energy Distribution on the New York, Westchester & Boston Railway . In: Electric Railway Journal, Volume XXXIX, No. 24, June 15, 1912, pp. 1004 ff.

- ^ A b c McGraw Publishing Company (Ed.): New Steel Cars for the New York, Westchester & Boston Railway . In: Electric Railway Journal, Volume XXXIX, No. 13, March 30, 1912, pp. 492 ff.

- ^ McGraw Publishing Company (eds.): Repair Shop of the New York, Westchester & Boston Railway . In: Electric Railway Journal, Volume XL, No. 23, December 14, 1912, pp. 1186 ff.

- ↑ RAIL LINE IS ADDED TO SUBWAY SYSTEM In: The New York Times. May 16, 1941, p. 25.

- ↑ SUBWAY TRAINS RUN TO DYRE AVE. In: The New York Times. May 7, 1957, p. 37.