Scottish Gaelic language

| Scottish Gaelic (also: Gaelic) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | 57,375 in Scotland, 1,500 in Canada, 1,600 in the United States, 800 in Australia and 600 in New Zealand | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

gd |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

gla |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

gla |

|

The Scottish Gaelic language ( Gàidhlig / ˈkaːlʲikʲ / ; outdated also Ersisch ) is one of the Celtic languages and is spoken today in parts of Scotland , namely on the islands of the Inner and Outer Hebrides , in the west of the Scottish Highlands and in Glasgow . However, not all speakers, especially in Glasgow, are native or first-time speakers .

The language belongs to the Goidelic branch of the island Celtic languages and is closely related to Irish and Manx . The close relationship with the Irish language can be explained by the immigration of Scots from Ireland to Scotland since the 4th century.

terminology

Scots

Scottish Gaelic should not be confused with Scots , which developed from Anglo-Saxon and is therefore one of the Germanic languages .

Ersisch

The outdated term Ersisch refers to the fact that Scottish Gaelic was called "Irish" even by native speakers (e.g. Martin Martin) until at least the 17th century. This was probably obvious to the speakers of the time, since Irish was the written language for Scottish Gaelic up until this time . The name "Ersisch" (English Erse ) is a corruption of the word Éireannach (Irish).

history

General development of Scottish Gaelic

Around the 4th century, Irish-speaking population groups, mainly from the small kingdom of the Dál Riata in Northern Ireland , emigrated to nearby Scotland and settled there permanently. For centuries, two small empires of that name existed, one in Ireland and one in Scotland. Although immigrants were able to conquer by far the largest part of Scottish territory, Scotland has never been fully Irish or Gaelic in its history .

Cultural relations with Ireland remained very close until the 17th century. The largely standardized written Irish language was used throughout the Middle Ages . First evidence of an independent development of Scottish Gaelic is contained in the Book of Deer (probably 10th century). Its irregular orthography gives some indications of an independent Scottish pronunciation . However, it cannot be assumed with certainty that at this time we can already speak of an independent language . At that time, Scottish Gaelic was probably just a dialect of Irish ( classical Gaelic ). Only the so-called Leabhar Deathan Lios Mòir (Book of the Dean of Lismore) from the early 16th century provides reliable evidence that Scottish has moved so far from Irish Gaelic that there are two closely related but separate languages. This composite manuscript contains text passages in the Scottish Gaelic language, which are written in an orthography that is strongly based on the pronunciation of the Scots at the time . This quasi “external” view of the language gives direct insights into the pronunciation of the time, which would not be possible using the usual orthography. Today it is generally assumed that the linguistic separation of Scottish from Irish began between the 10th and 12th centuries, but that it was only possible to speak of an independent language from the 14th or 15th centuries.

While Scottish Gaelic was not spoken in the Lowlands since the late Middle Ages (14th century) and was replaced by Scots , it was displaced from the southern and eastern areas of Scotland in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the western highlands, on the other hand, Anglicisation did not begin until the 19th and 20th centuries. This pushing back of the ancestral language was mainly caused by external influences, beginning with the collapse of the clan society after 1745 and especially intensified after the introduction of compulsory schooling in 1872 with the exclusive use of the English language (the use of Gaelic in class or on the School grounds were often even punished).

Extinct dialects in southern Scotland

The term Scottish Gaelic refers to the dialects spoken in the Scottish Highlands, the Highlands . The Scottish Gaelic dialects that were once common in the Lowlands have died out. Of these dialects, the Glaswegian Gaelic, which was preferred in Galloway, was the last dialect to be used until modern times. From the 18th century, Lowland Gaelic was replaced by Lowland Scots, a Germanic language derived from Middle English. It is said that the last village to have speakers of Lowland Gaelic was the isolated town of Barr in Carrick, Ayrshire.

There is no secure language border between the northern and southern Scottish Gaelic dialects that is based on topographical conditions. Place names do not differ linguistically between Argyll and Galloway . The dialects on both sides of the North Channel (Straits of Moyle), which once connected Scottish Gaelic with Irish as a continuum, have died out. The closest Irish dialect to Scottish Gaelic is Ulster Gaelic in County Donegal (Gaoth Dobhair Gaeltacht ), which has a somewhat conservative vocabulary and older grammatical structures than the official standard Irish, which is based on the southern Irish dialects.

What is commonly referred to as the Scottish Gaelic language has its lexical, grammatical and phonetic basis in the Outer Hebrides and Skye , i.e. the Gaelic dialects spoken on the western islands (the only exceptions here are Arran and Kintyre ). The dialect of Lewis stands out, however, because the pronunciation of the "narrow" ( palatalized ) / r / as [ð] and the tonality are due to Norse influences from the Vikings .

Extinct dialects in Eastern Scotland

Scottish Gaelic in eastern Scotland ceased to exist in the 19th century. The dialects in Sutherland were more archaic in vocabulary and grammar than those of the Western Isles, where the majority of Scottish Gaelic speakers live. These native speakers often mocked the Gaelic of the speakers in Sutherland. Due to the stigmatization of speaking “bad” Gaelic, this devaluation of their dialect ensured that the language change to English was accelerated and the use of Gaelic in everyday life came to an abrupt end.

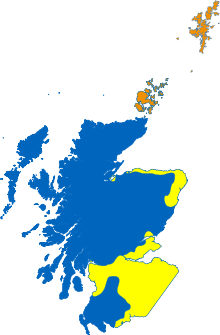

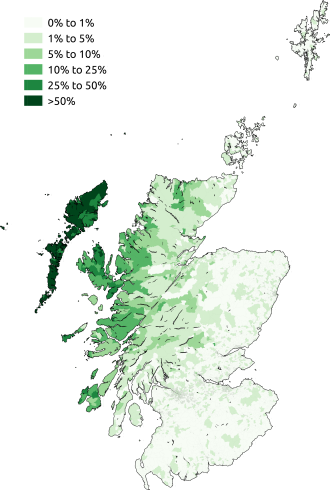

Today's distribution

The number of speakers is 57,375 according to the 2011 census. That is approximately 1.1 percent of the population of Scotland (1.1% of the population over three years old). Compared to the 2001 census, there is a decrease of 1275 speakers. In 2011, around 87,056 people stated that they had knowledge of Gaelic, 6,226 fewer than in 2001, when 93,282 people stated that they had knowledge. Despite the slight decrease, the number of speakers under the age of 20 increased. Scottish Gaelic is not an official language in the European Union or the United Kingdom. (The only Celtic language that has de jure official status in the UK is Welsh in Wales). Still, Scottish Gaelic is classified as a native ( indigenous ) language in the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages , which the British government has also ratified. In the Gaelic Language Act (Gaelic Language Act) of 2005, a language development institute was set up, the Bòrd na Gàidhlig , "with a view to securing the status of the Gaelic language as the official language of Scotland".

Outside Scotland, there are about 1,500 Scottish Gaelic speakers in Canada, mainly in the province of Nova Scotia . 350 people there stated in the 2011 census that they speak Gaelic as their mother tongue.

Gaelic is the everyday language used mainly in the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles / Na h-Eileanan Siar) by around 75% of the population. Since the Gaelic Language Act 2005, Gaelic has also been officially used in the public parlance there (Comhairle nan Eilean Siar). The highest percentage of Gaelic speakers are in Barvas on Lewis; slightly over 64% of the residents use the language in everyday life (2011 census). On the mainland of the north-west coast of the highlands, Gaelic is not used in any municipality by more than about 25% of the population. Most of the speakers live in the Kyle of Lochalsh in the highlands. In Glasgow (Scottish Gaelic Glaschu, pronunciation: [ ˈglasəxu ]) there are relatively many Gaelic speakers for a city. There has also been a Gaelic-language school (consisting of a pre-school, elementary school and secondary school) Sgoil Ghàidhlig Ghlaschu with around 630 students in Woodside since 2006 , which has made it its mission to promote the Gaelic language also among the younger generation. All subjects except English are taught in Gaelic. Since 2013 there has also been a Gaelic-speaking primary school in the Scottish capital, Edinburgh, the Bun-sgoil Taobh na Pàirce with around 230 students on Bonnington Road. In addition to a handful of really bilingual primary schools in the Outer Hebrides, Gaelic is mainly used in so-called Gaelic-medium units (GMU) at 61 primary schools with almost 2000 students (as of 2005). Of these schools, 25 were in the Western Isles , 18 in the Highland, and 6 in Argyll and Bute . The age structure and thus the prognosis of the language for the future is still rather unfavorable, since it is mostly only used in daily use by people over 40 years of age. Still, there are successful efforts to cultivate Gaelic; Gaelic programs ( culture , children's programs , etc.) with English subtitles are regularly broadcast by the BBC and Scottish Television . The BBC also maintains a Gaelic radio program Radio nan Gaidheal . In Stornoway on Lewis, Grampian Television also has Gaelic programs.

The BBC launched the BBC Alba channel on September 19, 2008 , which can be seen on satellite television in Scotland. Transmission via Freeview (DVB-T) and cable television is planned. The daily news broadcast to Là (The Day) can be received worldwide on the Internet.

Percentage of Gaelic speakers by age, Scotland, 2001 and 2011

| Age | 2001 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Total share | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| 3-4 years | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| 5-14 years | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| 15-19 years | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| 20–44 years | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| 45–64 years | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| 65–74 years | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| 75 and older | 2.0 | 1.7 |

The number of Gaelic speakers is only slightly decreasing. It is positive that the proportion of speakers under the age of 20 has increased. The number of speakers has stabilized over the past ten years. All Gaelic speakers are bilingual (including English).

Despite the close relationship to Irish, speakers of the other language cannot communicate with one another without problems, which is why they are often forced to switch to English as the lingua franca . In addition, a dialect of Scottish Gaelic, Canadian Gaelic , is spoken in Nova Scotia ( Cape Breton Island ) in Canada, according to conservative estimates, by around 500 to 1000 mainly elderly people.

Gaelic speakers in Scotland between 1755 and 2011

| year | Scottish population |

Gaelic (monoglott) |

Gaelic and English (bilingual) |

Total share of Gaelic speakers |

| 1755 | 1,265,380 | 289,798 (22.9%) | unknown | unknown |

| 1800 | 1,608,420 | 297,823 (18.5%) | unknown | unknown |

| 1881 | 3,735,573 | 231,594 ( 6.1%) | unknown | unknown |

| 1891 | 4,025,647 | 43,738 | 210,677 | 5.2% |

| 1901 | 4,472,103 | 28.106 | 202,700 | 4.5% |

| 1911 | 4,760,904 | 8,400 | 183.998 | 3.9% |

| 1921 | 4,573,471 | 9,829 | 148,950 | 3.3% |

| 1931 | 4,588,909 | 6,716 | 129,419 | 2.8% |

| 1951 | 5,096,415 | 2,178 | 93,269 | 1.8% |

| 1961 | 5,179,344 | 974 | 80.004 | 1.5% |

| 1971 | 5,228,965 | 477 | 88,415 | 1.7% |

| 1981 | 5,035,315 | - | 82,620 | 1.6% |

| 1991 | 5,083,000 | - | 65,978 | 1.4% |

| 2001 | 5,062,011 | - | 58,652 | 1.2% |

| 2011 | 5,295,403 | - | 57,602 | 1.1% |

Peculiarities of the language

The Scottish-Gaelic language shares some peculiarities with the other living Celtic languages , including the grammatical changes in the initial sound of words ( lenation , i.e. “weakening” of consonants, as well as nasalization) and the basic word order verb-subject-object . Questions are therefore not formed by placing the verb in front, as in German, but mainly by question particles together with the dependent verb form. Similar to some northern European languages, voiceless plosives are pre- aspirated (pre-breathed): tapadh leat - ("thank you"): / ˈtaxpa ˈlʲæt /

Lening:

| Expression | pronunciation | translation |

|---|---|---|

| màthair | [ maːher ] | mother |

| mo mhàthair | [ mo vaːher ] | my mother |

| to cù | [ ən kuː ] | the dog |

| do chù | [ do xuː ] | your dog |

| Tha mi brònach | [ ha mi ˈbrɔːnəx ] | am-I-sad = I am sad. |

| Tha mi glè bhrònach | [ ha mi gleː ˈvrɔːnəx ] | am-I-very-sad = I am very sad. |

| A bheil thu brònach? | [ a veɪl u ˈbrɔːnəx ] | Question-particles-are-you-sad? = Are you sad? |

grammar

Scottish Gaelic is syntactically simpler than its direct precursor, Old Irish . The sentence structure follows the VSO pattern , not SVO as in English. An essential feature is the lenation , which z. B. is used for the formation of the preterital forms, the case or to illustrate the gender and the plural form.

Examples:

- òl - dh'òl - drink (en) - drank

- am bàrd (nom.), a 'bhàird (gen.), a' bhàrd (dat.)

- a bhròg - his shoe, a bròg - her shoe

- a 'bhròg - the shoe, na brògan - the shoes

Unlike most Indo-European languages, a verbal noun takes on many of the tasks of the non-existent infinitive. Another peculiarity is the habitual concept for activities that recur regularly or represent general facts (“the earth is round”, “she goes to work every day”).

Phonology

1. Vowels

| grapheme | phoneme | example |

|---|---|---|

| a | [ a ] | bata |

| à | [a:] | bàta |

| e | [ ɛ ] , [ e ] | le, teth |

| è, é | [ɛ:] , [e:] | sèimh, fhéin |

| i | [ i ] , [i:] | sin, ith |

| ì | [i:] | mìn |

| O | [ ɔ ] , [ o ] | poca, arched |

| ò, ó | [ɔ:] , [o:] | pòcaid, mór |

| u | [ u ] | door |

| ù | [u:] | door |

| grapheme | phoneme | example |

|---|---|---|

| ai | [ a ] , [ ə ] , [ ɛ ] , [ i ] | caileag, iuchair, geamair, dùthaich |

| ài | [aː] , [ai] | àite, bara-làimhe |

| ao (i) | [ɰː] , [əi] | caol, gaoil, laoidh |

| ea | [A] ,[ e ],[ ɛ ] | geal, deas, bean |

| eà | [ʲaː] | ceàrr |

| èa | [ɛː] | nèamh |

| egg | [ e ] , [ ɛ ] | hurry, ainmeil |

| egg | [ɛː] | cèilidh |

| egg | [eː] | fhéin |

| eo | [ʲɔ] | deoch |

| eò (i) | [ʲɔː] | ceòl, feòil |

| eu | [eː] , [ia] | ceum, fire |

| ia | iə , [ia] | biadh, dian |

| ok | [ i ] , [ᴊũ] | fios, fionn |

| ìo | [iː] , [iə] | sgrìobh, mìos |

| iu | [ᴊu] | piuthar |

| iù (i) | [ᴊuː] | diùlt, diùid |

| oi | [ ɔ ] , [ ɤ ] | boireannach, goirid |

| òi | [ɔː] | fòill |

| ói | [O] | cóig |

| ua (i) | [uə] , [ua] | ruadh, uabhasach, duais |

| ui | [ u ] , [ ɯ ] , [ui] | muir, uighean, tuinn |

| ùi | [uː] | you in |

Consonants - graphemes

| bra | fh | mh | ph | ch before a, o, u | ch before e, i | chd | gh before e, i | th | ie |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| / v / | /H/-/-/ | / v / | / f / | / x / | /H/ | / xk / | / y / | /H/ | / y / |

| bha | fhuair | mhath | phiseag | hole | chì | cuideachd | taigh | tha | dh'f½h |

| was | found | Well | kitten | lake | I will see | also | House | is | went |

The grapheme / bh / can be silent inside the word as in “leabhar” (book) - / ljioar /. The grapheme / fh / is mostly silent like in "glè fhuar" (very cold). The grapheme / mh / sounds a bit more nasal than / bh /.

2. Lening (softening, belongs to the initial mutations ) changes plosives (b, p, t), nasals (m) and fricatives (f, s): The initial mutation occurs, for example, after the possessive pronoun “mo” (my).

| Plosive b | Plosive p | Plosive t | Nasal m | Fricative f | Fricative s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| botal (bottle) | piuthar (daughter) | tunnag (duck) | muc (pig) | fearann (country) | saighdear (soldier) |

| mo bhotal | mo phiuthar | mo thunnag | mo mhuc | mo fhearann | mo shaighdear |

| [ v ] | [ f ] | [ h ] | [ v ] | [ - ] | [ h ] |

3. Nasalization still recognizable in Irish only exists as an echo, e.g. B. to còmhnaidh [ ən ̃ɡɔːniː ] instead of [ ən kɔːniː ] ˈʲɡ

4. unvoiced plosives (P, T, c (k)) experienced in most Scottish dialect a preaspiration (tapadh: [ taʰpə ]); on Arran , on the North Sea coast and in other dialects, however, this pre-aspiration is absent. As a result, there are several pronunciation variants : [ h p, h t, h k], [xp, xt, xk] ( Lewis ), [p, t, xk], [hp, ht, xk].

5. Some sounds (phonemes) are not used in German. Example: ao [ ɯ ] or dh / gh [ ɣ ] , [ χ ]

6. Scottish Gaelic is more conservative in spelling than Irish, which has deleted some silent graphemes for the sake of simplicity: Scottish: “latha” (day) / la: /; Irish "la" (day) / la: /.

7. In Scottish Gaelic, the emphasis is on the first syllable, for example Alba (Scotland), Gàidhlig (Gaelic), in words of English origin the emphasis of the language of origin is often adopted, for example giotàr (guitar), piàno (piano).

Verbs

There is no infinitive; non-finite verb forms are: verbal nouns, past participle and imperative. Verbs are determined by person / number (only in the subjunctive), mode ( indicative / subjunctive ), gender verbi ( active / passive ) and tense . There is also an independent verb form, also known as a statement form, as well as a dependent form, which is derived from the basic form of the verb and can be significantly different from the statement form in the case of irregular verbs.

To be the verb"

There are two forms of the verb "sein": the verb "bi" and the copula form "is".

1. "bi" is used when characterizing a noun through adjectives and phrases: "Iain is happy" - Tha Iain toilichte . The conjugated form is "tha" in the present tense in declarative clauses and takes different forms in negative and interrogative clauses (dependent form):

| Declarative sentence | negation | question | negated question | Tense |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tha mi toilet. | Chan eil mi toilet. | What about the toilet? | After hurry thu toilet? | Present |

| Bha mi toilet. | Cha robh mi toilet. | To robh thu toilet? | After robh thu toilet? | preterite |

| Bidh mi toilet. | Cha bhi mi toilet. | Am bi thu toilet? | After bi thu toilet? | Future tense |

| Bhiodh tu toilet. | Cha bhiodh tu toilet. | At biodh tu toilet? | After biodh tu toilet? | conjunctive |

(Last line: In the subjunctive, the verb changes in the 1st person sing. To: Bhithinn toilichte and in the 1st person plural to: Bhitheamaid toilichte )

2. The copular form “is” is used for identification and definition, the connection of two nouns. There are two patterns: "X is Y" is used to connect two specific nouns: Is mise Iain (I am Iain). "Y is an X" is used to connect a definite and an indefinite noun. Is e Gearmailteach a th 'ann an Iain . (Iain is a German). “Is” is often abbreviated to “'S”.

| Declarative sentence | negation | question | negated question | Tense |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is mise Iain. | Cha mhise Iain. | Am mise Iain? | After mise Iain? | Present + future |

| Bu mhise Iain. | Cha bu mhise Iain. | Am bu mhise iain? | After bu mhise Iain? | Past tense + subjunctive |

The affirmation and negation of verbs

There are no words for “yes” and “no” in the Scottish Gaelic language. The verb serves as an answer to yes / no questions by repeating it in the statement form for "yes" or in the dependent form for "no".

| question | affirmation | negation | translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| What about the toilet? | Tha. | Chan rush. | Are you happy? Yes No. |

| To robh leabhar agad? | Bha. | Cha robh. | Did you have a book Yes No. |

| An deach thu? | Chaidh. | Cha deach. | Did you go Yes No. |

Tempora

There are separate verb forms only for the past tense , future tense and subjunctive, as well as passive and impersonal forms. The present tense can only be expressed by the progressive form: "X is swimming" (Tha X a 'snàmh, literally: is X when swimming).

| Present | preterite | Future tense | conjunctive | Verb stem |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tha ea 'dùineadh an dorais. | Dhùin e an doras. | Dùinidh e an doras. | Dhùineadh e an doras. | dùin - close |

| Tha e ag òl cofaidh dubh. | Dh'òl e cofaidh dubh. | Òlaidh e cofaidh dubh. | Dh'òladh e cofaidh dubh. | òl - drink |

| Tha ea 'fàgail na sgoile. | Dh'fhàg e an sgoil. | Fàgaidh ee an sgoil. | Dh'fhàgadh e an sgoil. | fàg - leave |

| Tha ea 'leughadh leabhar. | Leugh e leabhar. | Leughaidh e leabhar. | Leughadh e leabhar. | leugh - read |

In the present tense, the progressive form appears with bi + verbal nouns - "He is on / while drinking black coffee."

In the past tense, the verb stem, which is identical to the command form, is lenited if possible, verbs with a vowel at the beginning of the word are preceded by “dh”, verbs with “f” are lenited and additionally provided with “dh” for l, n, r the lenation does not appear in the written language, only in the spoken word. In the dependent form, the word "do" is placed in front of the verb: An do dhùin ..?; cha do dh'òl ..; dh'fhàg to do ... .

In the future tense, the ending “(a) idh” is added to the verb stem in the statement form, only the verb stem is used for the dependent form: An dùin ...; chan òl ..; on fàg ..? After a relative pronoun, the verb is lenited and given an “(e) as” ending: S e seo an doras a dhùineas mi . (This is the door I'll close.)

In the subjunctive, the verbal form is lenited and the ending “(e) adh” is added to the verb stem, the ending is retained for the dependent form, but the lenition is canceled: An dùineadh ...; chan òladh ..; am fàgadh ..? In the 1st person singular / plural verb and personal pronouns merge into one word: dh'òlainn (I would drink); dh'òlamaid (we would drink).

- All other tenses are put together: perfect , past perfect , future tense II .

- There are ten irregular verbs (besides bi and is); these are also the most frequently used verbs.

- Habitual, recurring activities are expressed in the present by the simple future tense, in the past by the subjunctive.

Nouns

- Nouns are determined by four cases : nominative ( accusative form is identical), genitive , dative and vocative as well as by two genera : masculine and feminine .

- Genitive and dative forms of some nouns and adjectives are formed by vowel umlaut within the word: alt - uilt, clann - cloinn (e), gorm - guirm .

Adjectives

- With a few exceptions, the adjective comes after the noun it describes.

- a 'chaileag bhàn - the blonde girl

- to duine maol - the bald man

- 'S e duine eireachdail a th' ann - He's a handsome man.

- 'S e duine laghach a th' ann - He's a nice man.

- However, a small number of adjectives come before the noun and lenate it:

- to ath-sheachdain - next week.

Prepositional pronouns

- In addition to the simple form, many prepositions have fused forms with personal pronouns / possessive pronouns : ann (in), annam (in me), nam (in mine).

The numbers from 1 to 10

The particle “a” comes before the numerals if it is not used together with a noun. The numerals 1 and 2 create a lenition (breath) of the noun and the singular form is used for the plural. Female nouns have a dual form, with the last consonant being slender: dà chois, but “aon chas” and “trì casan”!

| Gàidhlig | German | Gàidhlig cat m. (Cat) | Gàidhlig cas f. (Foot leg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ah-aon | one | aon chat | aon chas |

| a dhà | two | dà chat | dà chois |

| a trì | three | trì cait | trì casan |

| a ceithir | four | ceithir cait | ceithir casan |

| a cóig | five | cóig cait | cóig casan |

| a sia | six | sia cait | sia casan |

| a seachd | seven | seachd cait | seachd casan |

| a h-ochd | eight | ochd cait | ochd casan |

| a naoi | nine | naoi cait | naoi casan |

| a dyke | ten | dyke cait | dyke casan |

The numbers from 11 to 1,000,000

For some time now, two systems have existed side by side for the numbers from 20 to 99: a relatively modern system of ten (decimal system) and a traditional system of twenty (vigesimal system). In schools these days, however, the system of ten is mostly taught and used. For Numeralia over twenty the vigesimal system is mostly used, especially for years or dates. The singular of the noun is used for the numbers 21–39. The noun comes in front of the number “fichead” (twenty): “two cats to twenty” (= 22); "A cat ten to twenty" (= 31); two (times) twenty cats and one (= 41) or "four (times) twenty thousand - four hundred - two (times) twenty and thirteen" (= 80,453)! A thousand is “mìle” and a million is “muillean”. In the decimal system, only the singular of the noun is used.

| Gàidhlig | German |

|---|---|

| a h-aon deug | 11 |

| a dhà dheug | 12 |

| a trì deug | 13 |

| a ceithir deug | 14th |

| a cóig deug | 15th |

| a sia deug | 16 |

| a seachd deug | 17th |

| a h-ochd deug | 18th |

| a naoi deug | 19th |

| a fichead | 20th |

Nouns with numerals Vigesimal system and decimal system

| Gàidhlig (Vigesimal) | Gàidhlig (decimal) | German |

|---|---|---|

| dà chat ar fhichead | fichead is a dhà cat | 22 cats |

| naoi cait ar fhichead | fichead is a naoi cat | 29 cats |

| aon chat deug ar fhichead | trithead is a h-aon cat | 31 cats |

| dà fhichead cat is a h-aon | ceathrad is a h-aon cat | 41 cats |

| dà fhichead cat is a dhà dheug | caogad is a dhà cat | 52 cats |

| trì fichead cat is a sia | seasgad is a sia cat | 66 cats |

| trì fichead cat is a seachd deug | seachdad is a seachd cat | 77 cats |

| ceithir fichead cat is a h-ochd | ochdad is a h-ochd cat | 88 cats |

| ceithir fichead cat is a naoi deug | naochad is a naoi cat | 99 cats |

| mìle is dà fhichead cat | - | 1040 cats |

| trì mìle seachd ceud ceithir fichead is a naoi cat | - | 3789 cats |

| ceithir fichead mìle ceithir ceud dà fhichead is a trì deug cat | - | 80,453 cats |

| dike ar fhichead | trithead | 30th |

| dà fhichead is a dyke | caogad | 50 |

| trì fichead is a dyke | seachdad | 70 |

- In addition to cardinal numbers and ordinal numbers, there are separate numerals for people from 1 to 10

- the Indo-European dual is still recognizable: the word for “two” dà is followed by the dative singular in the lenited form, if possible. (e.g. aon phiseag: one kitten; dà phiseig: two kittens; trì piseagan: three kittens.)

Language examples

| Gàidhlig | German |

|---|---|

| A bheil Gàidhlig agad? | Do you speak gaelic |

| Ciamar a tha thu? | How are you? |

| Cò as a tha sibh? | Where are you from? |

| Tha mi glè thoilichte! | I am very happy! |

| Chan hurry with idleness. | I do not understand. |

| Dè thuirt thu? | What did you say? |

| Tha mi duilich! | I am sorry! |

| Latha broad sona dhuit. | Happy Birthday. |

| Tha gradh agam place! | I love you! |

| Tha mi 'g iarraidh a dhol dhachaigh | I want to go home |

A-màireach

Èiridh sinn aig seachd uairean 's a' mhadainn a-màireach agus gabhaidh sinn air bracaist anns a 'chidsin. Ithidh mise ugh agus tost. Ithidh mo charaid, an duine agam hama agus ugh. 'S toil leamsa uighean ach cha toil leam hama. Òlaidh mi cofaidh gun bainne, gun siùcar agus òlaidh e tì làidir le bainne agus dà spàinn siùcar. Tha sinn glè shona seo! Tha e grianach agus an latha breagha an-diugh! Tha sinn a 'falbh anns a'sgoil a-màireach. Coimheadaidh sinn air an tidsear fhad 'sa sgrìobhas ise rudan air a' chlàr-dubh.

Translation: In the morning

We get up at seven in the morning and have breakfast in the kitchen. I eat eggs and toast. My friend eats some ham and egg. I love eggs, but I don't like ham. I drink coffee without milk, without sugar, and he drinks strong tea with milk and two spoons of sugar. We are very happy here. It's sunny and a beautiful day today. We go to school in the morning. We see our teacher who is writing something in the class register all the time.

Comparison between Scottish Gaelic and Irish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic is called Gàidhlig in Scotland , Irish Gaelic is called Gaeilge in Ireland . Using the example of the question "How are you?" the differences should become clear.

Examples:

Gàidhlig (Leòdhais) - Dè mar a tha thu?

Gàidhlig (standard) - Ciamar a tha thu?

Gaeilge (Ulaidh) - Caidé mar a tá tú ?, or Cad é mar atá tú?

Gaeilge (standard) - Conas atá tú?

Gàidhlig - Chan eil airgead agam. (I have no money.)

Gaeilge - Níl airgead agam. (I have no money.)

Irish Gaelic : Scottish Gaelic

Gael: Gàidheal (Gäle)

lá: latha (day)

oíche: oidhche (night)

isteach: a-steach (enter)

scoil: sgoil (school)

páiste: pàisde (child)

gan: gun (without)

údarás: ùghdarras (authority)

oifig: oifis (office)

oscailte: fosgailte (open)

bliain: bliadhna (year)

raidió: rèidio (radio)

rialtas: riaghaltas (kingdom)

parlaimint: pàrlamaid (parliament)

oileán: eilean (island)

See also

literature

- Michael Klevenhaus : Textbook of the Scottish Gaelic language. Buske, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-87548-520-2 .

- Bernhard Maier : Dictionary Scottish Gaelic / German and German / Scottish Gaelic. Buske, Hamburg 2011. ISBN 978-3-87548-557-8

- Katherine M. Spadaro, Katie Graham: Colloquial Scottish Gaelic. Routledge, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-20675-4 .

- Henry Cyril Dieckhoff: A Pronouncing Dictionary of Scottish Gaelic. Gairm Publications, Glasgow 1992, ISBN 1-871901-18-9 .

- Morag MacNeill: Everyday Gaelic. Gairm Publications, Glasgow 1994, ISBN 0-901771-73-2 .

- Donald John Macleod: Can Seo. Gaelic for Beginners. Pitman Press, Bath 1979, ISBN 0-563-16290-2 .

Web links

- Linguae-celticae.org Very detailed regional studies on the situation of the language; in addition, information on all Celtic languages.

- Schottisch-gaelisch.de Gaelic courses in Germany

- Sabhal Mòr Ostaig Gaelic courses in Scotland, Isle of Skye (in Gàidhlig / English)

- Stòr-Dàta Briathrachais online dictionary Gàidhlig / English

Individual evidence

- ↑ Census 2011 Scotland: Gaelic speakers by council area ( Memento of February 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Oifis Iomairtean na Gaidhlig ( Memento of 17 October 2013 Internet Archive )

- ^ Australian Government Office of Multicultural Interests ( Memento of May 19, 2010 on WebCite ) (PDF). As of December 27, 2007.

- ^ After David Ross: Scottish Place-Names . Birlinn, Edinburgh 2001, ISBN 1-84158-173-9 , pp. 24 ff .

- ↑ Gàidhlig Ghallghallaibh agus Alba-a-Deas ("Gaelic of Galloway and Southern Scotland") and Gàidhlig ann an Siorramachd Inbhir-Àir ("Gaelic in Ayrshire") by Garbhan MacAoidh, published in GAIRM numbers 101 and 106.

- ↑ James Crichton: The Carrick Convenanters 1978

- ↑ 2011 Census of Scotland, Table QS211SC, May 30, 2014.

- ↑ Scotland's Census Results Online (SCROL), Table UV12, May 30, 2014.

- ↑ Scottish Government, “A 'fàs le Gàidhlig”, September 26, 2013, of May 30, 2014.

- ^ "Official text of the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005". Statutelaw.gov.uk. May 26, 2011, from March 27, 2014

- ↑ 2011 Census of Canada, Topic-based tabulations, Detailed mother tongue (192). Statistics Canada, as of June 30, 2014.

- ↑ Glasgow Gaelic School - Sgoil Ghaidlig Ghlaschu

- ↑ www.myjobscotland.gov.uk , April 7, 2013

- ↑ Radio nan Gaidheal: Gaelic-language radio program of the BBC

- ^ BBC News

- ↑ News broadcast of the gaelic television program

- ↑ Source: National Records of Scotland © Crown copyright 2013

- ^ MacAulay: Gaelic demographics, table KS206SC of the 2011 Census

- ^ Henry Cyril Dieckhoff: A Pronouncing Dictionary of Scottish Gaelic. Gairm Publications, Glasgow 1992.

- ^ Katherine M. Spadaro, Katie Graham: Colloquial Scottish Gaelic. Routledge, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-20675-4 .

- ↑ Colin Mark: At the Faclair Gàidhlig-Beurla. Routledge, London 2004, ISBN 0-415-29761-3 , p. 706.

- ^ Morag MacNeill: Everyday Gaelic. Gairm Publications, Glasgow 1994.