Sucked trumps

Sucked trumpet ( English , "suction trumpet", Spanish trompeta aspirada ) is a rare group of aerophones , similar in shape to natural trumpets , in which the sound is generated with the vibrating lips by sucking in air from a hollow body. For the sucked trumpets , no German-language name has yet been established and in the Hornbostel-Sachs systematics published in 1914 there is no instrument-based classification of a category of " sucked tubes " that is analogous to the wind instruments . The MIMO arranged in a supplement of the 2017 sucked trumpets in the trumpet group (423) a new subset Sucked (tubular) labrosones (423.123.1) to.

Sucked trumpets can consist of animal horns, conically wound strips of bark, long, approximately cylindrical wooden tubes or plant tubes. They were widespread in ritual music in Siberia , where they are referred to, among other things, by the Tungus name byrgy . On the American continent, ritually used sucked trumpets occurred in Canada , Mexico ( chirimía ) and Paraguay . The nolkin is best known in Chile . A special group are the bones found in Neolithic tombs on the Swedish island of Gotland and used in North America in the presence of hunters for decoy calls, which consist of two or three differently sized, telescopically assembled bones.

Classification and design

The Hornbostel-Sachs system, published in 1914, is based on the previously known types of instruments. Curt Sachs mentions in his Reallexicon of musical instruments from 1913 under the keyword “Byrgy” their special sound generation “by drawing in the air”, but he does not go into it further below. The system undertakes a classification for the (actual) wind instruments (group 42) on the upper level according to the acoustic possibilities of sound generation. In all wind instruments, a stream of air coming from the outside, which is periodically interrupted when entering a hollow body, sets the air inside vibrating, producing an audible sound. In the trumpet subgroup (423), the vibrating lips of the player cause the blown wind to vibrate and produce a loud sound. The trumpet player's lips are closed when at rest and, according to the principle of the upholstered pipe, open periodically due to the blowing pressure.

The sound of the sucked trumpet is also formed with the lips, but these are slightly open in the starting position and are periodically closed by drawing in air through a tube open at the bottom, so that the air flow sucked into the tube is periodically stopped. As with a natural trumpet, the fingerhole-free sucked trumpet can produce tones of the natural tone series . The frequencies of the lip movements must match the oscillation frequencies of the air column in the tube so that clear tones are produced.

Since no agreement has yet been reached among instrument experts , the sucked trumpets form an instrument group that has not yet been classified in the Hornbostel-Sachs system. A third group of aerophones related to the wind direction are those in which the wind sweeps past the sound-generating element in the usual way of playing in both directions (422.3). These include the harmonica instruments, including the mouth organs , in which the punch tongue produces a different sound depending on the wind direction, and the jew’s harps .

Ernesto Gonzalez made a first attempt at classifying the Chilean nolkin , who in an essay in 1986 classified the Mapuche musical instruments according to the Hornbostel-Sachs system and at the same time differentiated their origins between a pre-Columbian origin, a Spanish import and an influence of the Chilean military. González assigns the nolkin to the end-blown straight natural trumpets (423.121.1) according to their shape, without taking into account the different tone formation caused by blowing or sucking in air. The distinction between the wind direction was lost when the Hornbostel-Sachs system was translated into English. While the German original version contains the category (actual) wind instruments (42), its English title is wind instruments proper . The fact that the system explicitly refers to hollow bodies into which blows are made can be seen from the definition of trumpets (423): "The wind receives intermittent access to the column of air to be set in vibration through the intermediary of the vibrating lips of the blower." Translation, the word "Bläser" is just as ambiguous as player ("player"). The sucked trumpets insert in the appropriate places the form typology by another circuit division (approximately "blown" or "sucked longitudinal trumpets"), would mean that this distinction be supplemented with the remaining trumpet instruments would and would complicate the order. Jens Schneider (1993) therefore suggests adding a new category sucked (tubular) trumpets (423.123) at the level of end-blown trumpets ( longitudinal trumpets , 423.121) and side blown trumpets ( transverse trumpets , 423.122) and adding these according to the form to be further subdivided. For this, too, the word "Bläser" in German would have to be replaced by "Player". Another suggestion aims to generally remove all words with the meaning “bubbles / wind instrument” from the category of aerophones (4) and an end divider “blown” (-3), “sucked in” (-4) and “blown” everywhere and sucked in "(-5). This would mean the most extensive restructuring. No change to the previous classification would be needed if the low systematics in the convenient addition by José Pérez de Arce and Francisca Gili (2013) were accepted. The two extend the existing level of natural trumpets (423.1, only notes of the natural tone series) and chromatic trumpets (423.2, with a device to produce a chromatic scale) by a group of trompeta de la aspiracción (423.3, trumpets whose tones are created by suction) . This and some other changes are intended to take the “American perspective” into account.

A method of sound generation in aerophones, which was originally also disregarded, characterizes the membranopipes . For them, the Musical Instrument Museums Online (MIMO), an international committee that wants to coordinate and make digital information about musical instruments in museums available, introduced another wind instrument category (424) in the Hornbostel-Sachs system in 2011. In an appendix from November 2017, which contains some additions and minor corrections to their 2011 classification, Jens Schneider's (1993) suggestion reappears to create a new group in the Hornbostel-Sachs system for the nolkin . It was named sucked (tubular) labrosones (423.123.1) and divided into instruments without a mouthpiece (423.123.11) and with a mouthpiece (423.123.12). The term labrosones (from Latin labium , "lip", and sonus , "sound, noise", for example "lip tweeter") goes back to Anthony Baines (first used in 1976), who gave a more coherent definition for the category of brass instruments ( corresponds to "brass instruments", in which Hornbostel-Sachs wanted to introduce "trumpets"). Labrosones can refer to vibrations of the lips in either direction of the wind.

The outer shape is important for the categorization of the aerophones on the lower levels, because sucked trumpets can in principle consist of the same variety of materials and shapes as natural trumpets and natural horns , which are defined solely by the method of sound generation with the lips. In addition to straight tubes made of plant material, clay or bones, the primitive trumpets also include curved animal horns and rounded vessels such as calabashes and snail horns . Not all musical instruments with these trumpet shapes depend on lip vibrations. The player hums, sings or speaks into some vessels in order to take advantage of the resonance amplification or sound distortion caused by the vessel. The sound frequencies generated can sometimes in turn produce corresponding lip vibrations. The Australian didgeridoo is at such a transition to the sound generation of a trumpet .

One possible reason why the sucked trumpets are played by drawing in breath is that the high notes are easier to produce this way. In order to achieve high notes in a trumpet, the lips must be taut. Blowing spreads the lips apart, making tensing more strenuous, while drawing in air promotes lip tension. With a thin and preferably tapered tailpipe, it is also easier to keep the lips close together and thus airtight. In addition, the soft area of the lips in the oral cavity vibrates when sucking in.

distribution

Natural trumpets and horns are mainly blown lengthways around the world, while animal horns in Africa such as the South African phalaphala are usually blown from the side. The oldest trumpet-shaped wind instruments were probably used as voice distorters in order to drive away evil spirits in magical rituals or to imitate the voice of a spirit. They also retained the magical aspect of the wooden trumpets belonging to the sphere of the shepherds and the metal trumpets (such as the karna ) used in military environments .

Apart from the Neolithic bird-bone instruments, sucked trumpets are no different in shape from the simple conical natural trumpets or horns. The inner diameter of the tube at the upper end is only a few millimeters because it has to be held between the lips. Like the trumpets, the sucked trumpets are often associated with magical rituals. In addition to Siberia, Central and South America, “suction trumpets” also used to occur in northern and northeastern Europe - there as swan bones yus' pöl'an - but they were practically unknown in the rest of Europe. Jeremy Montagu (2006) nevertheless considers it possible that the discovery of an approximately 190 centimeter long wooden wind instrument from the 2nd millennium BC in County Mayo in western Ireland in 1791 . When sucked trumped was played. This mayophone , made up of two slightly conical halves and probably once wrapped in a spiral with a sheet of bronze sheet, is said to have been blown with a single reed , according to popular belief .

The snail horn, which is mainly blown from the side, is widespread throughout Oceania . It is a traditional signal or ritual instrument. Jeremy Montagu mentions the ethnologist Hans Fischer (1958), who refers to an unusual way of playing the snail horn on the island of Mangareva , reported by Te Rangi Hīroa in 1938. Accordingly, the snail horns on this island were played by suction.

Gotland bird bones

The origin of the sucked trumpets is unknown. Certain forms of Neolithic bird bones may not have been blown as flutes or whistles as is the custom, but may have had a reed or were played by suction to imitate bird calls. This assumption was expressed by Riitta Rainio and Kristiina Mannermaa (2012) about the discovery of 44 swan bones in 1986 in a woman's grave in Ajvide on the island of Gotland , which are dated to the Middle Neolithic (around 2900 to 2300 BC). In the case of a group of five artifacts consisting of two swan bones with different diameters pushed into one another, the smaller hole of 4 millimeters appears ideal for use with a reed or as a "suction trumpet". The larger inside diameter is around 10 millimeters with a total length of around 7 centimeters. The narrower tube acts as a mouthpiece when sucking in and the wider tube determines volume and sound. Replicas of these swan bones can easily be played as a lengthwise flute or by suction, in which case they produce an unusually loud sound.

In their reports published in 1998 and 2002, the excavators assumed that the swan bones were flutes; in later investigations this was doubted. The side perforations on some pieces of bone (always three on the top and three opposite on the bottom) appear unsuitable as finger holes for playing the flute. If Ajvide's swan bones were used for sound production at all, other researchers besides the musical archaeologist Riitta Rainio also consider their use as sucked tubes to be the most likely.

Tennessee bird bones

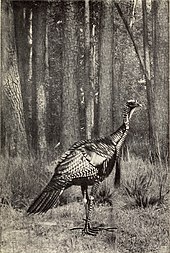

Up to the present day there are reports of bird bones from which sounds are elicited by suction. Hunters in North America most commonly use turkey wing bones to make decoy calls to hunt these very wild birds. The American businessman Edward Avery McIlhenny, who worked as a bird ringer, explained in a book on turkey hunting in 1914 that the rapid drawing in of air with such a wing bone can generate several calls to attract turkeys effectively. Typically, the enticing instruments, like the Neolithic finds, consist of two bones of different sizes, the radius and ulna of the turkey or swan, which are scraped to the right size at the ends, 10 to 40 millimeters deep into each other and connected airtight with a bowel or string or with tree resin become. Occasionally, three-part instruments have a humerus with a larger diameter attached to the lower end in order to amplify the sound. In North America, the tradition of attracting birds when hunting by imitating bird sounds within shooting range can be traced back to the 18th century.

Corresponding two-part bird bones from prehistoric times were found in Eva in the US state of Tennessee . They come from a settlement of hunters, fishermen and gatherers who lived from 8000 or 6000 to around 1000 BC. Was inhabited. The nine excavated bird bones are laterally imperforate and poorly preserved than the artefacts from Ajvide, but, like there, they are in two parts. The found layer of bird bones is dated to 5700 to 4700 BC. Dated. In the excavation report from 1961, the two-part bird bones are explained as presumed flutes . Howard L. Harlan (1994), an expert in the manufacture of turkey callers, however, recognized the found objects as early forerunners of these traditional hunting instruments.

The birdbone (and trumpet-shaped) aerophones generally have no finger holes. However, one-piece bird bone decoy whistles with a finger hole have been found in New Mexico . The two-part bird bones from the Ajvide and Eva sites were made from the wing bones of large birds using the same methods. Chest cocks and swans are most suitable, in which the diameter of the ulna is 5 to 9 millimeters and the radius is 8 to 13 millimeters. The ulna of the finds are 5.5 to 10.5 and the radius 3.0 to 6.0 centimeters long. If not broken, the upper end, which the player puts between the lips, has a notch or two notches opposite. The fundamental tones generated with both prehistoric sucked trumpets have a frequency range between 600 and 900 Hertz . Today's two-part turkey bones lure instruments are 15 to 20 centimeters in length and are larger than the prehistoric ones.

Byrgy

In addition to the Tungusic word byrgy , several Turkic languages in Siberia , which like Tungus belong to the Altaic languages , have names for different forms of sucked trumpets : purgu, abyrga, syynpyrgyzy and amyrga . From this it is concluded that this type of instrument was known a long time ago among the hunters of North Asia who used it to hunt deer ( Altai-Maral ) and elk . Curt Sachs (1913) calls the byrgy a Hunter Instrument Siberian Khakassians ( "Kačinzen") which mimic instrument with the wooden the cry of a doe to the male lure. Predominantly Turkic people from Manchuria might sucked trumpets at Mongols , Tungus , west to the Ugric -speaking peoples, and have spread to Russia, where she from the Komi and Udmurt under the name tschiptschirgan were taken.

Three types of sucked trumpets are known throughout this region : The first type has a cylindrical tube made of plant material that is otherwise used to make flutes, such as a hollowed out alder or willow branch or a bamboo cane.

The sucked trumpets , which are made from strips of bark in a spiral, are conical and correspond to the usual bark trumpets. These are typical very old pastoral instruments in the European and Asian north, which were also found in New Zealand, South America and the Cree Indians of Canada. The trumpets, often made from birch bark, included the neverlur in Scandinavia and the truba or taure in Latvia .

The third type, like the alphorn, consists of a round piece of wood that has been split lengthways into two halves, hollowed out and put back together again. These wooden trumpets, which are also part of the shepherd's instruments, such as the bazuna in northern Poland, the fakürt in Hungary and the trembita in the Ukraine, are usually wrapped in birch bark or linden bark. To this type belong the byrgy of the Khanty in western Siberia and the similar instrument of the tofalars in southern central Siberia. Both have a carved mouthpiece and a wooden tube about 80 centimeters long, which expands to 4 to 6 centimeters in diameter at the lower end. The pyrghy the local Khakassians is wrapped in regular intervals with strips of birch or willow bark, hold the timber halves. The sound produced by suction resembles the call of a roe deer. The type of instrument - where still available - is used ritually, for example in shamanic ceremonies. The Tschiptschirgan of the Udmurts consists of a 1.5 to 2 meter long tube and, like the musical bow kon-kón of the Mari, is one of the musical peculiarities of the Volga Federal District .

Nolkin

Design

The first description of the nolkin among the Mapuche comes from the linguist Rodolfo Lenz (1863–1938) in his folklore studies ( Estudios araucanos, 1895). The nolkin is of pre-colonial origin and could have existed as early as the 11th century, although the type of wind instrument is not clear from the early Spanish reports.

For the tube of the nolkin is Senecio otites used, to the genus Senecio belonging thistle plant in Chile with wide umbels of the Mapuche lolkin or liglolkin is called. This name passed on to the aerophone. Other spellings besides nolkin are ñolkin, ñorquin, lolkin and lolkiñ . The shrub plant Valeriana viriscens , which belongs to the valerian genus, can be used as an alternative . The tube is 1 to 1.5 meters long and has a narrow diameter of 4 to 5 millimeters on the inside and a little more on the outside at the top. The gradually increasing outer diameter is 15 millimeters at the lower end, according to another description 2 to 3 centimeters. If the upper pipe diameter is too large, a thinner bamboo blow-in pipe is inserted. The tube is divided along its entire length by a series of knots that narrow the inner diameter to 3 to 5 millimeters at these points. As a special feature among the sucked trumpets , the nolkin has a cattle horn attached to the bottom for sound amplification. To match the diameter of the horn and tube, the tube end is first wrapped with woolen cord, then the horn is attached and tied on the outside with the woolen cord. The end of the cord is then stretched to a hole drilled in the mouth of the funnel and tied there. Due to the different lip position compared to the trumpets, the player does not put on an instrument mouthpiece , but rather sticks the tube end, which is pointed at a 45-degree angle on two sides, between the lips. He positions the tube on the side of the mouth and inclines it slightly downwards. It was not until the Spaniards introduced cattle after their colonial conquest of South America in the 16th century. With the nolkin as a pre-Columbian musical instrument, a bell made of a rolled leaf or wickerwork could have been used in the past instead of the cow horn .

Closest in shape to the nolkin is the larger and deeper sounding trutruka with a two to five meter long straight bamboo tube and a bell made of a curved cow horn attached in the same way. The trutruka is a blown natural trumpet like the smaller, but otherwise identical, corneta . Another wind instrument that is much easier to play than the trumpets is the small single-tone flute pifüllka ( pifilca ), of which some specimens made from animal bones have been preserved in museums. Otherwise the pifüllka is made of hardwood with one hole, occasionally - like a double flute - with two parallel holes. It has no finger holes and is closed (closed) at the lower end. The wind instrument troltroklarin , which was made from a plant called troltro ( Cynara cardunculus or Silybum marianum ), has disappeared. In addition, there is the cattle horn kull kull , which is blown through a side hole and was introduced by the Spanish cavalry as a loudly sounding signaling instrument .

Style of play

The Mapuche are a people who live in the central parts of Chile and in neighboring Argentina . The nolkin is preferred on the Chilean coast because the thistle plant thrives there best, and also in the entire Mapuche area. All instruments were and are played by men, while the Idiophone (multiple vessel rattles and mouth harp Birimbau are) a domain of women.

The range for all wind instruments is low as in the songs sung the Mapuche and includes up to six, up to eight notes even when practiced in exceptional cases nolkin poker players could produce more tones. Each melodic phrase revolves around a central note, with nolkin players often ending a phrase with a glissando to a high note. The duration of a melodic phrase depends on how long the player can inhale. With its almost cylindrical long tube, the nolkin produces tones that roughly correspond to the overtone series . The cow horn has no influence on the pitch. A typical instrument produces the tone sequence e 1 - a 1 - c sharp 1 - e 2 - g 2 - a + 2 from the 3rd to the 8th partial . Even if the nolkin sounds quieter than the trutruka , it stands out in the orchestra with the beauty of its clear, fine sound as soon as the other instruments take a back seat . Because of its delicate voice, the nolkin is the preferred instrument of young people, stated the Chilean composer Carlos Isamitt (1887–1974) in the first detailed description of the nolkin in 1937.

The nolkin is or was used for shamanic and festive rituals. The machitun , the healing ceremony of the shaman ( machi ), and the religious fertility festival ngillatum , which usually takes place twice a year, are at the center of the Mapuche ritual music. The essential instrument of the machi , which it needs to fall into a trance, is the shaman's drum, kultrún , a flat wooden kettle drum. The same rhythmic patterns that the machi uses to maintain their magical abilities are also part of the music at the great ngillatum festival. There some 100 participants dance to the rhythm of several kultrún and the tones of the wind instruments trutruka, corneta and pifüllka . The quieter sounding nolkin is more likely to be used in smaller ensembles at other festive events. While the trutruka can hold its own , the nolkin and the other traditional wind instruments of the Mapuche are increasingly being displaced by the influence of the national Latin American musical styles. In contrast, there are efforts by Mapuche cultural organizations to revive indigenous culture and the playing of traditional musical instruments.

Chirimía

In Mexico , chirimía primarily refers to a double-reed instrument made of a cylindrical wooden tube with up to ten finger holes, played in folk music and religious ceremonies . The name can literally be translated as “my chirp” and derived from Spanish chirriar , “creak, chirp”. With the Spaniards, this name and so-called wind instruments with single or double reeds became widespread in Central and South America. In the early days of the conquistadors , every wind instrument and an entire ensemble could be called chirimía . By the 1990s, the reed instrument chirimía had become rare in Mexico. The Catalan spelling xirimía stands for variants of the European shawm that are still in use , furthermore xeremia denotes a double pipe pipe in Ibiza and xeremia a bagpipe in Mallorca .

Under the Spanish name chirimía there was also a sucked trumpet in Mexico with a thin tube about two meters long, the bell of which consisted of a calabash . According to the Mexican ethnomusicologist Samuel Martí (1906–1975) from 1955, this instrument was blown on church towers in the states of México , Puebla , Guerrero , Morelos and Oaxaca on Good Friday. In addition to Martí's statement, there is only a vague reference to the name chirimía known as “a kind of trumpet” in a lexicon entry from 1984 in the specialist literature .

Cattle horn in Paraguay

The Swedish ethnographer Karl Gustav Izikowitz (1903–1984) reports in his extensive study of South American musical instruments from 1935 that the Guayaki Indians (Guayaquí, today Aché) living in eastern Paraguay do not blow cattle horns, but the air from a small opening in the Tip suck. The horn was therefore used as a signaling instrument.

The Brazilian ethnologist Herbert Baldus (1899–1970) provides a further description in an article published posthumously in 1972, which is based on field research. Baldus emphasizes that there is no attached mouthpiece, just a small hole in the thinly scraped tip. The cattle horn served as a sign. A long ringing tone is followed by several short tones that mean "come". The signal can also be called. Other Guayaki wind instruments mentioned by Baldus are a calabash flute ( vessel flute ) with two burnt-in finger holes that produce three tones, and a flute made of Chusquea ramosissima (called takuapi , a type of bamboo ), which is closed at the bottom and has three finger holes . The length of a museum horn is 25 centimeters measured on the outside and the opening diameter is 7.5 centimeters. This makes it much smaller than the Mapuche's horn kull kull . Further descriptions are not available.

literature

- Timo Leisiö: On Euro-Siberian Byrgy, or the Sucked Concussion Reed. Etno-Musikologian Vuosikirja, Volume 10 ( Proceedings of the European Seminar In Ethnomusicology Jyväskylä 1997 ) 1998, pp. 64-95

- Riitta Rainio, Kristiina Mannermaa: Bird Calls from a Middle Neolithic Burial at Ajvide, Gotland. Interpreting Tubular Bird Bone Artefacts by Means of Use-wear and Sound Analysis, and Ethnographic Analogy . In: Janne Ikäheimo, Anna-Kaisa Salmi, Tiina Äikäs (Eds.): Sounds Like Theory. XII Nordic Theoretical Archeology Group Meeting in Oulu April 25-28, 2012. Monographs of the Archaeological Society of Finland , 2, 2014, pp. 85-100, here pp. 89-92

- Riitta Rainio: Sucked Trumpets in Prehistoric Europe and North America? A Technological, Acoustical and Experimental Study. In: Ricardo Eichmann, Lars-Christian Koch, Fang Jianjun (eds.): Studies on music archeology X sound - object - culture - history. Lectures at the 9th Symposium of the International Study Group on Music Archeology in the Ethnological Museum of the State Museums in Berlin, 9. – 12. September 2014. Marie Leidorf, Rahden 2016, pp. 151–168

- Riitta Rainio, Kristiina Mannermaa, Juha Valkeapää: Recapturing the sounds and sonic experiences of the hunter-gatherers at Ajvide, Gotland, Sweden (3200–2300 cal BC). In: Journal of Sonic Studies, Volume 15, December 14, 2017

- Jens Schneider: The Nolkin: A Chilean Sucked Trumpet. In: The Galpin Society Journal , Volume 46, March 1993, pp. 69-82

Web links

- Tesoros Mapuche: “El Ñolkin” . Youtube video ( nolkin the Mapuche)

- Lef Caniupil - ñolkitun inaltu kutral. Youtube video ( nolkin the Mapuche)

- Ensemble Ülger - Vol I - Khakassia Youtube Video (Ensemble Ülger from Khakassia with a pyrghy made of birch bark, pictured 3: 05–3: 30)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Curt Sachs : Reallexicon of musical instruments, at the same time a polyglossary for the entire field of instruments. Julius Bard, Berlin 1913, sv "Byrgy", p. 65

- ↑ Sucked Trumpets. In: Grove Music Online, March 26, 2018

- ^ Ernesto González (Greenhill): Vigencias de instrumentos musicales Mapuches. In: Revista Musical Chilena, Volume 15, No. 166, Santiago, 1986, pp. 4-52

- ↑ Philipp Emmanuel Müller: The melodic structures of the Ülkantun - On the influence of universal sound principles on the orally traditional sound system of the Mapuche Indians . Herbert Utz, Munich 2009, p. 122f

- ↑ Jens Schneider, 1993, p. 79

- ↑ José Pérez de Arce, Francisca Gili: Clasificación Sachs-Hornbostel de instrumentos musicales: una revisión y aplicación desde la perspectiva americana. In: Revista musical chilena , Volume 67, September 2013, pp. 42-80, amended Hornbostel-Sachs system in the appendix

- ^ Revision of the Hornbostel-Sachs Classification of Musical Instruments by the MIMO Consortium. MIMO addition to the Hornbostel-Sachs system from 2011

- ↑ ADDENDA and CORRIGENDA for the Revision of the Hornbostel-Sachs Classification of Musical Instruments by the MIMO Consortium, as published on the CIMCIM website. Appendix to the MIMO addition to the Hornbostel-Sachs system from November 2017

- ^ Anthony Baines: Brass instruments: Their History and Development. Faber & Faber, London 1976, p. 40

- ↑ Klaus P. Wachsmann : The primitive musical instruments. In: Anthony Baines (ed.): Musical instruments. The history of their development and forms. Prestel, Munich 1982, pp. 13–49, here p. 45

- ↑ Jens Schneider, 1993, p. 74

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse : A Survey of Musical Instruments. Harper & Row, New York 1975, p. 785

- ↑ Riitta Raini, Kristiina Mannermaa, 2014, pp. 89–92

- ↑ Jeremy Montagu: Review by: Simon O'Dwyer: An Guth Cuilce / The Mayophone. Study and Reproduction. Rahden 2004 . In: The Galpin Society Journal, Volume 59, May 2006, pp. 272-276, here p. 273

- ↑ Simon O'Dwyer: To Guth Cuilce / The Mayophone. Study and Reproduction. In: Ellen Hickmann, Ricardo Eichmann (Hrsg.): Studies on music archeology 4. Music archeology Source groups: soil documents, oral tradition, record. Music-Archaeological Sources: Finds, Oral Transmission, Written Evidence. (= Orient-Archaologie, Volume 15) Marie Leidorf, Rahden 2004 pp. 393–407

- ^ Hans Fischer : Sound devices in Oceania. Construction and play technique, distribution and function. Strasbourg 1958, reprint: Valentin Koerner, Baden-Baden 1974

- ↑ Te Rangi Hīroa : Ethnology of Mangareva, Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin No. 157, Honolulu 1938

- ↑ Jeremy Montagu: The Conch Horn. Shell Trumpets of the World from Prehistory to Today. Hataf Segol Publications, 2018, p. 106

- ↑ Riitta Rainio, Kristiina Mannermaa, 2014, pp. 89–92

- ^ Edward Avery McIlhenny: The Wild Turkey and its Hunting. Doubleday, Page & Company, New York 1914, p. 182

- ↑ Riitta Raini, Kristiina Mannermaa, 2014, p. 94

- ^ Howard L. Harlan: Turkey Calls. At Enduring American Folk Art. Harlan-Anderson Press, Nashville 1994

- ^ Riitta Rainio, 2016, p. 152

- ↑ Riitta Rainio, 2016, pp. 153–155

- ^ Werner Danckert: Hirtenmusik. In: Archiv für Musikwissenschaft, 13th year, issue 2, 1956, pp. 97–115, here p. 110

- ↑ Timo Leisiö: Byrgy . In: Grove Music Online, March 26, 2018

- ↑ Face Music - Traditional Instruments - Khakas people. face-music.ch (German)

- ^ Mark Slobin, Jarkko Niemi: Russian Federation. II. Traditional music. 2. Non-Russian peoples in European Russia. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ↑ Jens Schneider, 1993, pp. 69, 80

- ↑ Jens Schneider, 1993, p. 71f

- ↑ Juan A. Orrego-Salas: Araucanian Indian Instruments . In: Ethnomusicology , Volume 10, No. 1 ( Latin American Issue ) January 1966, pp. 48-57, here p. 51

- ^ Sarah Butler: Music Inside the Walls: Mapuche Expressive Culture and Identity in the Context of a Southern Chile Boarding School . (Master thesis) Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney, 2013, p. 61

- ^ Carlos Isamitt : Cuatro instrumentos musicales Araucanos. In: Boletín Latinoamericano de Música, Volume 4, Montevideo 1937, pp. 55-66

- ↑ Jens Schneider, 1993, pp. 74-76

- ↑ Dale A. Olsen: World Flutelore: Folktales, Myths, and Other Stories of Magical Flute Power. University of Illinois Press, Chicago 2013, p. 211

- ↑ John M. Schechter, Henry Stobart: Chirimía. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ↑ John M. Schechter: Chirimía. In: New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments , 1984

- ↑ Jens Schneider, 1993, p. 76f

- ↑ Karl Gustav Izikowitz: Musical instruments and other sound of the South American Indians, a comparative ethnographical study. Gothenburg 1935

- ↑ Jens Schneider, 1993, p. 77

- ↑ Herbert Baldus : The Guayaki of Paraguay . In: Anthropos , Volume 67, Issue 3./4, 1972, pp. 465-529, here p. 496

- ↑ Jens Schneider, 1993, p. 77f