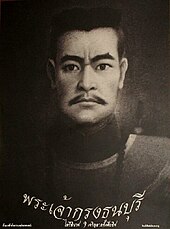

Taksin

Taksin the Great ( Thai ตากสิน มหาราช - ; in Thai historiography: Somdet Phrachao Krung Thonburi ("King of Thonburi"); * April 17, 1734 in Ayutthaya ; † April 6, 1782 (executed) in Thonburi ) , was King of Siam (Thailand) after the end of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya in 1767 until the beginning of the Chakri Dynasty .

Surname

As is common with high-ranking people in ancient Siam, the name Taksins changed several times in the course of his life when he took on new positions. Even posthumously, he was referred to by various names and titles. His real name was Sin , surnames did not exist in Siam at the time. With the assumption of the governor post in the province Tak he got the title Phraya Tak . Under this title he became known and sometimes his individual name was added to distinguish it, i.e. Phraya Tak (Sin) . In older western sources, which were not familiar with the Siamese naming conventions, he was later referred to as king, also as Phraya / Phya / Phaya Tak or Phyatak. During the turmoil of the war that led to the fall of Ayutthaya, he was probably briefly governor of Kamphaeng Phet , some sources therefore also refer to him as Phraya Kamphaengphet .

On his accession to the throne, like the kings of Ayutthaya before, he assumed a very long, auspicious title that manifested his claim to power, in which several elements from the names of earlier kings were included in order to derive continuity and legitimacy: Phra Si Sanphet Borom Thammikaratchathirat Borommachakkraphat etc. . (" Dharmic king of kings", "exalted world ruler "). In various Siamese royal chronicles he is referred to as King Ekathotsarot or Borommaracha IV . In current Thai histories he is called Somdet Phrachao Krung Thonburi ( สมเด็จ พระเจ้า กรุงธนบุรี , "King of Thonburi") because he was the only ruler who ruled from this capital. However, the name Phrachao Taksin ( พระเจ้าตากสิน ) has become common among the population . Since a cabinet decision in 1981 he has been nicknamed Maharat ( มหาราช , "the great").

Early years

Taksin was born in Ayutthaya as the son of a Chinese immigrant named Hai Hong (Thai: ไห ฮ อง ) and the Siamese Nok-Iang (Thai: นก เอี้ยง ) . Hai Hong, who was probably from Chaozhou (Teochiu) , was quite wealthy. He was allowed to operate amusement arcades in the capital, for which he had to pay taxes to the government, and carried the title Khun Phat Nai-Akon .

Taksin was adopted as a toddler by Chaophraya Chakri, the head of the Mahatthai (Ministry of the Northern Provinces). Legend has it that he noticed that his financial transactions had been particularly successful since then. Therefore he called the boy Sin (roughly: prosperity). Following tradition , Sin became a novice in a Buddhist monastery at the age of seven . After Sin left the monastery, he entered the king's service as a page. At the age of 20 he was re-ordained as a monk at Wat Kosawat Monastery. There he studied the scriptures and the Pali language for a full three years . According to another legend, he met the young Thong Duang (later King Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok (Rama I)) in the monastery . Both were prophesied later kingship by a Chinese fortune-teller, but neither took this seriously. After the three years Sin returned to him King Borommakot's court , where he became an assistant in the Mahatthai Ministry.

Governor and troop leader

After King Borommakot's death, Sin made civil and military careers under King Ekathat's reign . He became lieutenant governor in 1760, later governor of the Tak Province, which earned him the name Taksin ; his official title was Phraya Tak .

During the Siamese-Burmese War from 1764 he was a general in the army of the King of Ayutthaya. He is portrayed as a capable and brave military leader, but also as impulsive and headstrong. During the siege of Ayutthaya by the troops of the Burmese King Hsinbyushin , he commanded a fortified monastery just outside the city moat. There he took advantage of an opportunity to fire a cannon at the enemy without asking permission from the palace, as would have been his duty. For this he was brought to justice and severely disciplined.

Whether out of disgust for a leadership that placed traditional rules over military use or out of the knowledge that Ayutthaya could not be kept, Taksin and his subordinate troops evaded his superiors in November 1766 and occupied a fortress near the capital. When a great fire broke out in Ayutthaya in January 1767, he left the battlefield entirely and broke through the Burmese defensive ring with a force of about 1000 men in order to move south-east. A short time later, the Burmese took the capital and completely destroyed it. The king died or disappeared. Siam was on the ground, chaos and anarchy reigned in the country, and a doom and gloom spread.

Like Taksin himself, much of his unit was of Chinese descent , according to the historian Prince Damrong Rajanubhab . Their ethnic background may also have been a reason for their direction of movement: many Chinese settled on the eastern Gulf coast . They moved to Chon Buri and on to Rayong . There Taksin held a meeting at which he was proclaimed head (chao) in his own right in view of the dissolved state order in Ayutthaya . He even awarded feudal titles to local village heads, a right that actually belonged to the king. In June 1767, Taksin's army captured Chanthaburi , whose provincial governor had opposed him, probably because he was pursuing his own ambitions. As a result, he controlled the entire east coast with several smaller ports and associated ships.

In October 1767 - six months after the fall of Ayutthaya - he advanced with his army to the west, into the plains of central Thailand, which were then still occupied by Burmese. He took the Thonburi fortress and had the Burmese commander executed. The news of this alerted the headquarters of the Burmese occupation forces near Ayutthaya. However, the main army had already returned to Burma, and only a few thousand men remained to occupy it. Taksin opposed the troops deployed against him, won the first smaller skirmishes and finally overran the Burmese garrison. The Siamese troops subordinate to these may overflow to Taksin. The liberation of the old capital had more symbolic value, it also reinforced the charisma with which Taksin was able to achieve his goals.

Empire founder

Taksin did not have Ayutthaya rebuilt, but chose the small fortress town of Thonburi (now part of Bangkok) on the western bank of the Mae Nam Chao Phraya ( Chao Phraya River ) as the new capital. According to legend, he had a dream in which previous kings of Ayutthaya appeared to him and drove him out of the old royal city. But there were also rational reasons: the city fortifications of Ayutthaya had been destroyed, it would have been very laborious and possibly too long to rebuild them in order to repel a potential new attack by Burma. The rice fields around the old capital were also devastated during the war or at least not cultivated, which would have made supplies more difficult. The walls of Thonburis, however, were intact, it was strategically located and surrounded by cities that were also under the control of Taksin and his allies. In addition, Taksin was then only one of several rival warlords and had no way of knowing that he would assert himself as king of all of Siam. Practical and strategic considerations may therefore have been more important than symbolic links to the past.

Despite the relocation of the capital, he tried to maintain continuity with the old empire: he had King Ekathat solemnly cremated, which had not been done during the chaos of war. In addition, Taksin married four ladies-in-waiting of the old kingdom, daughters of high-ranking aristocrats, in order to connect with the old elite. Taksin's advisor eventually convinced him that the people, the military and the civil service wanted him to be king and he was crowned on December 28, 1767.

According to the contemporary French historian François-Henri Turpin, Taksin based his claim to rule primarily on his charity:

“It was under these unfortunate circumstances [of hunger and plague] that [Taksin] developed his compassionate character. The poor did not have to remain in want for long. The treasury, usually used for the maintenance of luxury, was opened for the relief of the needy. For money, foreign countries supplied the products that their own soil had not given. It was through his generous gifts that the usurper justified his claim to rule. Violations were punished and security restored. "

However, after the fall of the capital, the former area of Siam was split up into a large number of smaller states and rulers. Principalities that had been dependent on Ayutthaya as vassals, such as Nakhon Si Thammarat , became self-employed. Both the governor of Phitsanulok and a son of the former king Borommakot , who controlled Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat), declared themselves kings (vassals of Burma). A kind of "monastic republic" was formed around Fang in what is now the province of Uttaradit . The local monks had political and military ambitions contrary to their religious vows and took Phitsanulok in 1768.

In the same year, Taksin invaded Korat and gained control of the area. The following year he took Nakhon Si Thammarat. The northern Malay sultanates, including Patani , sent tribute to Thonburi in 1769. In 1773 he reinstated the exiled King Ang Non II in Cambodia , who recognized Taksin as overlord. In 1774 the kingdoms of Lan Na (present-day northern Thailand) and Luang Phrabang (present-day northern Laos) fell from Burma and came under the protection of Taksin. Chiang Mai and Nan were gradually snatched from the Burmese.

Taksin enforced inner order with a hard hand in all the chaos. The strictest penalties, even for minor offenses, were the order of the day. Less than two years after his accession to the throne, he accused two of his wives of cheating on him with other men. He had them raped publicly before their arms and heads were cut off. Since Taksin could not rely on old rulers or an influential family, he made many dangerous enemies. But he also found brilliant helpers, including the brothers Thong Duang and Surasi , who served him as military leaders from around 1770. After he had put down another uprising in Korat, Thong Duang was enfeoffed with the title Chaophraya Chakri in 1775 (he is the later founder of the Chakri dynasty ).

Securing the Empire and Conquests

Taksin was in a similar situation to that of the great King Naresuan two centuries earlier, who freed the country from its dependence on the Burmese and not only restored the kingdom of Ayutthaya, but even expanded it. This was also the aim of Taksin, as far as this can be seen from his actions. Burma held large areas of Southeast Asia under his control and, as a result of this encirclement, posed a great threat to Taksin's empire.

Taksin went even further than Naresuan had. In 1777, Taksin's generals conquered the kingdom of Champasak in southern Laos , and the following year Vientiane , which had remained loyal to the Burmese. Until the cession to France in 1893, the Lao states remained vassals of Siam. One of the loot from this period is the famous Emerald Buddha (today in Wat Phra Kaeo in Bangkok ). Hundreds of Laotian families were deported to the central Thai lowlands as workers. Even Cambodia did not remain quiet, and so the two generals Chaophraya Chakri and Surasi 1781 had to again be able to be entrusted with the reassurance.

Mental changes and judgment

During this time, strong personality changes made themselves felt in Taksin. He devoted himself excessively to meditation. According to the records of the explorer Johann Gerhard König from 1778, he hoped to become such a god and be able to fly through the air. The king claimed to be a Sotāpanna (Thai sodaban , "stream- entrant "), i.e. H. one who has reached the first stage on the path to enlightenment. Two monks confirmed him in the assumption that his special achievements and skills would prove that he had achieved this status. As such, he claimed to be above (ordinary) monks in the religious hierarchy, even if he was a layman. He therefore forced monks to bow to him, which was not customary before (according to the Theravada Buddhist idea, every single monk embodies the holy Sangha and does not have to bow to any layperson, no matter how high-ranking it is, not even to the king). However, much of the established clergy refused. He had stubborn whips, including monks and court members. In this way he made an enemy of an important part of the clergy and aristocracy. Contrary to what is claimed in many accounts of Siamese history, the point was not that Taksin allowed himself to be worshiped as a god, new Buddha or Bodhisattva .

Taksin is portrayed as increasingly paranoid. The French missionary Jean-Joseph Descourvières described him somewhat euphemistically as plus que demi-fou (“more than half crazy”). His fear of conspiracies against him, however, was not entirely unjustified - there was indeed dissatisfaction in circles of the traditional aristocracy (of which he himself had never belonged) and probably plans to overthrow him. As an upstart who had made an enormous rise to rulership in a lifetime, his own power base was thin. With politically unwise decisions and actions he had turned all relevant social groups against him: monks, long-established family dynasties, civil servants and merchants. Draconian punishments were pronounced on the smallest of occasions, he had people locked up, flogged and tortured in order to make them confess to acts they probably did not commit; their own family members were no exception.

This led to a rebellion under the leadership of a Phraya Sankhaburi (Phaya San), who forced Taksin to abdicate and to be ordained as a monk at Wat Chaeng (today: Wat Arun ). The news from the capital prompted Chaophraya Chakri, who was well connected with the most powerful families in the country, to return from Cambodia and take power. The rebels were arrested and executed, but Taksin's confidants and relatives such as his son Intharaphitak were also killed. Taksin was taken from the temple and put on trial. He was accused, among other things, of mistreating the Supreme Monk Patriarch and convicting subjects without trial. He was found guilty.

On April 6, 7, or 10, 1782, Taksin's death sentence was carried out. There are contradicting information about the method of execution : Either he was simply beheaded at the fortress Wichaiprasit , or according to the law on the execution of royalty with a sandalwood club (Thai: การ สำเร็จโทษ ด้วย ท่อน จันทน์ - Kan Samret Thot duai Thon Chan) from the 15th century Wrapped in a velvet sack and killed by a blow with a sandalwood club in the neck, as royal blood was not allowed to be shed. On the same day, Chaophraya Chakri ascended the throne as King Ramathibodi (later he was referred to as Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok or Rama I ). He founded the Chakri dynasty , which is still ruling today .

According to the Thai Royal Chronicles , Taksin was buried in the temple (wat) of Bang Yi Ruea Tai. Legend has it that instead of Taksin, someone else was executed and the deposed king was brought to Nakhon Si Thammarat in the south of the country , where, according to one variant, he became a monk, according to another, he lived in a luxurious palace until 1825.

In 1784, the new ruler Rama I had a subsequent burial ceremony for Taksin, with which his services to Siam were recognized, which he undoubtedly had to show.

In the Chenghai district of Shantou in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong , the possible home of his father, there is a tomb of King Taksin, which does not contain the remains, but the (presumed) robe of King Taksin.

effect

On October 27, 1981, he was posthumously awarded the title of "the great" (Maharat) by cabinet resolution. His coronation day, December 28th, is a national day of remembrance, but not an official holiday. The Taksin Maharat National Park in Tak Province is named after him. There are also numerous statues in various places in the country, such as Thonburi , Tak and Phitsanulok .

literature

- Jiří Stránský: The reunification of Thailand under Tāksin, 1767–1782. Society for Nature and Ethnology of East Asia, Hamburg 1973, DNB 830300341 .

Web links

- Taksin the Great ( Memento from August 10, 2002 in the Internet Archive ) Page about King Taksin the Great (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b The exact date is disputed: April 6 (DK Wyatt: Thailand a short history ), April 7 (Terwiel: Thailand's political history ) or April 10 ( Royal Gazette, เล่ม ๑๒๐, ตอน ที่ ๘๔ ก, หน้า ๔๑ )

-

↑ z. B. François Henri Turpin: History of the Kingdom of Siam. 1771. English version, Bangkok 1908. Facsimile at Applewood Books, Bedford MA 2009.

Adolf Bastian: Reisen in Siam in 1863. Facsimile at Unikum-Verlag, Barsinghausen 2013.

Meyer's travel books. World Travel. First part: India, China and Japan. Facsimile at BoD - Books on Demand, 2013.

Carl Ritter: The geography of Asia. Volume III, Berlin 1834. - ↑ Dhiravat Na Pombejra: Administrative and Military Roles of the Chinese in Siam during an Age of Turmoil, circa 1760–1782. In: Maritime China in Transition 1750–1850. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2004, p. 343.

- ↑ ML Manich Jumsai: Popular History of Thailand . Chalermnit, Bangkok 2005, p. 354.

- ^ BJ Terwiel : Thailand's Political History. From the Fall of Ayutthaya to Recent Times . River Books, Bangkok 2005, ISBN 974-9863-08-9 , p. 39.

- ↑ a b c B. J. Terwiel: Thailand's Political History. From the Fall of Ayutthaya to Recent Times . River Books, Bangkok 2005, ISBN 974-9863-08-9 , p. 40.

- ^ Terwiel: Thailand's Political History. 2005, p. 41.

- ^ A b Terwiel: Thailand's Political History. 2005, p. 42.

- ^ A b c Terwiel: Thailand's Political History. 2005, p. 43.

- ^ Terwiel: Thailand's Political History. 2005, p. 44.

- ^ François-Henri Turpin: Histoire civile et naturelle du royaume de Siam Et des révolutions qui ont bouleversé cet Empire jusqu'en 1770. Costard, Paris 1771, p. 339. Original quote: “Ce fut dans ces circonstances malheureuses que Phaïa-Thaé développa son caractere compatissant. Les pauvres ne languirent pas longtemps dans le besoin. Le trésor public, épuisé ordinairement pour l'entretien du luxe, fut ouvert pour le soulagement des malheureux. L'étranger fournit à prix d'argent les productions que le sol de la patrie avoit refusées. Ce fut par ses largesses que l'usurpateur justifia les titres de sa grandeur. Les abus furent réformés, & la sûreté rétablie. "

- ^ Wyatt: Thailand. A short history. 2004, p. 123.

- ↑ a b Patit Paban Mishra: The History of Thailand. Greenwood, 2010, p. 69.

- ^ David K. Wyatt : Studies in Thai History . Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai 1994, ISBN 974-7047-19-5 , pp. 136 f.

- ^ David K. Wyatt : Thailand. A short history. 2nd Edition. Yale University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-300-08475-7 , p. 126.

- ^ Terwiel: Thailand's Political History. 2005, p. 54.

- ^ Terwiel: Thailand's Political History. 2005, p. 55.

- ^ Terwiel: Thailand's Political History. 2005, pp. 57-58.

- ↑ Quoted in David K. Wyatt: Thailand. A short history. 2nd Edition. Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai 2004, p. 127.

- ^ Wyatt: Thailand. 2004, p. 127.

- ^ Terwiel: Thailand's Political History. 2005, pp. 58-60.

- ^ Terwiel: Thailand's Political History. 2005, p. 60.

- ↑ a b Nidhi Eoseewong: Thai politics in the reign of the King of Thon Buri . Arts & Culture Publishing House, Bangkok 1986, p. 575.

- ↑ For detailed information, see Wikipedia: The execution of Thai royalty

- ^ Wyatt: Thailand. A short history. 2004, p. 128.

- ↑ Patit Paban Mishra: The History of Thailand. Greenwood, 2010, p. 69.

- ^ David K. Wyatt : Thailand. A short history. 2nd Edition. Yale University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-300-08475-7 , p. 128.

- ↑ King Taksin the Great

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Taksin |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Taksin the Great; Taksin Maharat; Phaya Tak; Tak Sin; Borommaracha IV. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of Siam |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 17, 1734 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ayutthaya |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 6, 1782 |

| Place of death | Thonburi |