Constitutional laws of the German Reich 1933–1945

The constitutional laws of the German Empire were from 1933 through the seizure of power by the Nazi Party in the German Empire until its demise in 1945 applicable state law . The essential transition to this was the ordinance of the Reich President for the protection of the people and the state of February 28, 1933, with which the individual basic rights of the Weimar Reich constitution were suspended for an indefinite period. With this ordinance, the Nazi state ended a long constitutional tradition that began with the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679. The Enabling Act of March 24, 1933 abolished the separation of powers . With the synchronization laws of March and April 1933, the federal state was converted into a central state .

These constitutional laws, which were shaped by National Socialist ideology and came into force mainly between 1933 and 1935, were the basic laws of the National Socialist state. They were referred to as constitutional laws because they usually concerned constitutionally regulated issues such as legislative competence , national structure , nationality , state symbols , military sovereignty , territorial existence and political parties and formed the core of the national leader state. However, the basic state laws were not summarized in a "Hitler Constitution", either in a single document or in several.

Elements of the national constitution

Insofar as a codification of the “overall national constitution” of the Nazi regime is sought in vain, the program of the guiding political norms can be found in individual thematic constitutions. When assessing constitutional law, it is noticeable that the individual regulations represent “elements of a constitution” at best. In order for the National Socialist program statements to be implemented into applicable law, they had to acquire constitutional status as a priority state law. Legislation to which this was granted were, in historical sequence, the Enabling Act , the Provisional Coordination Act , the Second Coordination Act , the Law Against the Formation of Parties , the Law on Securing the Unity of Party and State , the Law on the Reconstruction of the Reich , the German municipal code and the Reichsstatthaltergesetz .

Abolition of fundamental rights and creation of new principles

After the Reichstag fire at the end of February 1933, most of the basic rights were effectively suspended by Hindenburg's emergency decree . From then on, there were just as few guarantees for personal freedom , freedom of opinion and the press as, for example, for the protection of property , the confidentiality of letters or the inviolability of the home .

After the successful Reichstag election at the beginning of March 1933, the Enabling Act followed in the same month, which granted the Reich government its own legislative and amendment competence, which also extended to laws with constitutional status . This removed the separation of powers between parliament and the Reich government. Immediately there were no more laws preserving the rule of law , which Adolf Hitler's "crown lawyer" Carl Schmitt referred to in his work State, Movement, People : "The Weimar Constitution no longer applies."

In contemporary literature, a National Socialist constitutional state of ethnic origin has been asserted; this had nothing in common with the traditional western protection of individual legal interests. Within six months, around 100,000 opponents of National Socialism were arrested on the basis of the Reichstag Fire Ordinance. Measures by the secret state police (Gestapo) could no longer be attacked in the administrative courts from 1936 , and from December 1933 the communities were no longer allowed to bring an action against interference in their self-government sovereignty. Also with the exclusion of legal recourse, the professional civil service, which had been cleared of unpleasant people, was restored in April of that year .

The Volkish Principle

The völkisch principle is the constitutional side of the illusion of the mandate of rule of the Germanic race, whose leading representatives derived a claim to world domination and a Europe-wide policy of conquest. According to the National Socialist view, the ideal of the "purity of species" of the people served as the basis for militant anti-Semitism and thus formed the basis for political community.

Volkish inequality

The ethnic inequality describes the relationship to "non-Germans" and to "foreigners". Peoples and individuals are fundamentally unequal, and the German people are " master race ". According to the jargon of the authorities, an internalized awareness of “species equality” gives rise to the ability to expose “species diversity”, which helps to separate the friend from the enemy. The segregation of Jews from the life of the German people, with legal consequences, was made clear from this point of view. With the Reichsgericht , the highest judiciary also joined the view that Jews were legally incomplete. From this thesis of human and ethnic inequality (“inequality and inequality”), the National Socialist power and terror system sucked in a central, comprehensive domestic and foreign political self-justification.

The national equality

A principle of "equality between people" was pure nonsense in Hitler's eyes. The Nazis was expressed as a natural law inequality and diversity of people. In order to use the good and convincing sound of the terminology of the principle of equal treatment and to tie in with it, it was superimposed with the phrase "national equality", which is to be established in legal language. In contrast to the principle of equal treatment in the Weimar Constitution , which entitles the state but is also obligatory , the promised "national equality" shortened the individual's freedom of action and gave no guarantees of action or omission with regard to the state's obligation to the citizen. Instead, the principle was that the Führer could determine the sphere of activity of the individual “ Volksgenossen ” as part of the “ Volksgemeinschaft ” and that the private character of individual existence was abolished. A sphere that was free of state influence no longer existed.

Transfer of legislative power from the Reichstag to the Reich government

Reich laws could also be passed by the Reich government without the involvement of the Reichstag . This also applied to constitution-amending laws, insofar as they did not repeal the constitutional organs of the Reich Government and the Reichstag. Treaties with foreign states could also be concluded without the consent of the Reichstag. The Reichstag could still be involved as before. Of the 993 new laws under National Socialism, only eight laws were passed by the Reichstag. The transfer of legislative competence was originally limited to April 1, 1937. It was twice extended for a limited period by the Reichstag and was extended for the first time on May 10, 1943 for an indefinite period. Nevertheless, the Enabling Act should transfer real legislative power to the government. In C. Schmitt one can read that the liberal-constitutional separation of government and legislation was undesirable and had to be overcome in the long run.

Coordination of the countries

The alignment of the federal states took place in several stages. With the provisional law for the alignment of the states with the Reich of March 31, 1933, a Reich government law, both the state parliaments and citizenships as well as the municipal self-governing bodies such as local councils, district and district assemblies were dissolved and re-formed according to the number of votes that were in the election for the German Reichstag on March 5, 1933, within each country or in the area of the electoral body, the nominations were allotted. In this election, the NSDAP had become the strongest force with 43.9% of the vote, even though it had missed an absolute majority. The votes cast on the Communist Party were lost without replacement. The only exception was the Prussian Landtag , which was re-elected at the same time as the Reichstag on March 5, 1933. A dissolution of the Reichstag also resulted in the dissolution of the representative assemblies of the federal states. Legislative competence was transferred to the state governments.

A little later, Reich governors were appointed. They could appoint and dismiss the chairman of the state government, dissolve the state parliament and order new elections. They had to ensure that the guidelines drawn up by the Reich Chancellor were implemented . The Reichsstatthalter was the main ruler in the country. With a law of the Reichstag at the beginning of January 1934, all sovereign rights of the states were transferred to the Reich and the synchronization was completed. The state governments remained in place, but were subordinated to the Reich government as Reich funds authorities. The state parliaments were abolished; the states, on the other hand, remained as Reich administrative districts with a special property law position and retained their property, including the state forest . But they were no longer states. The Reichsstatthalter were only needed for special direct access. They were placed under the Reich Ministry of the Interior and lost the right to report directly to the Führer. The Reichsrat was dissolved by the Reich Government Act. With this federalism had been eliminated altogether, which in turn justified the dissolution of the Reichsrat .

New constitutional law through government law

With the law on the rebuilding of the empire , the government gained the power to set completely new constitutional law without being limited to changes to the Weimar constitution.

The abolition of the imperial colors black, red and gold

From March 12, 1933, the black-white-red flag of the empire and the swastika flag had to be hoisted together. This was the departure from the colors of the German Confederation (1848–1866) and the state symbol of the Weimar Republic. From September 17, 1935, the swastika flag was the imperial, national and trade flag.

Special exclusions and systematic persecution of Jews

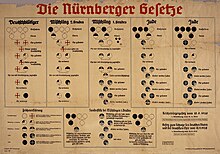

According to the so-called law for the restoration of the civil service of April 7, 1933, civil servants who had at least one Jewish grandparent were to be retired. A temporary exception was made for civil servants who had been civil servants since August 1, 1914 and earlier, and for front-line soldiers and their fathers and sons. The " front fighter privilege " had been requested by Reich President von Hindenburg in a letter to Hitler as an exception. Due to the “ Hereditary Health Act ” (mostly supposedly) “hereditary sick persons” could be rendered sterile against their will and that of their guardians. The “ hereditary health courts ” responsible for the decision only made a decision taking into account the interest in preventing hereditary offspring without weighing up the interests of the “hereditary disease”. The Reich Citizenship Law differentiated between citizens and Reich citizens. Reich citizens could only be citizens of " German or related blood ". A Jew was not allowed to be a citizen of the Reich and was not allowed to hold public office. A Jew was considered to be someone who was descended from at least three “fully Jewish by race” grandparents. Since a “race” could not be proven, a legal fiction was resorted to: According to the first ordinance on the Reich Citizenship Law , a grandparent was considered “fully Jewish” if he belonged to the Jewish religious community. The same ordinance decreed the dismissal of the last Jewish officials who had remained in office according to the provisions of the “front-line fighter privilege”. The " Blood Protection Act " forbade Jews from marrying citizens of "German or related blood" and from extramarital relations. Both were punished as “ racial disgrace ” with penitentiary or prison.

The German Reich as a one-party state

With the " Law to Safeguard the Unity of Party and State " of December 1, 1933, the NSDAP became the only authorized party. This law established increased obligations towards leaders, people and state for members of the NSDAP and SA. Anyone who undertook to form a new political party could be punished with imprisonment for up to three years. Even for projects that were terminated at an early stage of preparation, the reduction in penalties customary for experimental and preparatory actions was not provided. By virtue of the law, the NSDAP became the “bearer of the state idea” and “inextricably linked” with the state.

The leader principle

After the death of Reich President Paul von Hindenburg , the office of Reich President was legally combined with the office of Reich Chancellor. As a result, the powers of the Reich President were transferred to the " Führer and Reich Chancellor" Adolf Hitler. Fuehrer was initially the leader of the NSDAP and the National Socialist movement. Only three weeks after the unification of the offices was it regulated that Führer is the “Führer of the German People and Reich”. The title Reich President could no longer be applied to Hitler. The Führer was the highest legislature, highest judge and ruler, in whose hands the supreme organizational power, the supreme command of the armed forces and the power of representation under international law were united. Governmental power was concentrated with the Fiihrer, and then all other state powers; the "volkish common will of the Führer" prevailed.

The legal status of the "national comrade"

There was no law that comprehensively and conclusively described the rights and duties of the “ national comrade ”. In principle, the “Volksgenosse” should represent the position granted to him by the Führer and serve as a “real follower”. This basic characteristic should be expressed accordingly depending on the facilities and strengths, readiness for action and performance. In essence, the rights of the family, property and the availability of labor were seen as the skeleton of the national, around which the body flesh of the new proclaimed "order of life" then closes. In the light of the ideological impetus, these core elements signified the reality of the “national constitution”. “Innate” political rights which the individual had for his own sake were not recognized. No individual attention was paid to the individual, he only drew his justification from the meaning and value of a structural cell of the “people's body”. In the context of the National Socialist legal conception, the individual did not ensure any legally relevant interest. Even before the Nuremberg Laws , this racial ideological approach was transferred to civil law by the later very controversial legal scholar Karl Larenz and argued there.

The people fell under class assignments. This is how the peasant class, the class of industry, the class of trade and craft, that of handicrafts, traffic, medicine, law, defense and education were categorized. There was also the state of the art and the cultivation of science. The Reichsnährstand , the Reich Chamber of Culture , consisting of the Reich press , theater and music chamber, were considered to be imperial estates . There was of course no professional law , because the National Socialist state became a unitary state and not a corporate state .

The judiciary

In order to preserve the appearance of legality, Hitler left many lawyers in office, including in the exposed Reich Ministry of Justice. As representatives of the traditional legal principles, they suspected the National Socialists and tried to defend the rule of law, but the ministerial resistance subsided to the same extent as the National Socialist pressure built up and increased. Hardly any different fared the highest court, the Reichsgericht, whose president Erwin Bumke was increasingly brought before he was finally relieved of his independence . When Otto Thierack was elected Minister from the ranks of the National Socialists in 1942, his notorious judges' letters were promptly issued . They served the goal of completely abolishing the independence of the judiciary.

The Association of National Socialist German Lawyers (BNSDJ) was founded in the late 1920s . In 1933, the BNSDJ took over the coordination of the judiciary in the federal states in the capacity of a "Reich Commissioner". The existing legal organizations were urged to dissolve so that they would functionally merge with the BNSDJ. Not only the German Association of Judges were affected by the pressure , but also the lawyers ' and notaries' associations . The organizations of judicial officers and bailiffs also had to submit to the BNSDJ. After law professors, bar associations and legal journals were brought under external control, the chamber districts ultimately lost their independence in order to be subordinated to the Reich Chamber with instructions. The retrospective confirms that the majority of lawyers not only adapted to the circumstances that were destructive to the rule of law, but even gave general encouragement.

The leader as chief judge

Under the pretext of an attempted putsch (see “ Röhm Putsch ”), Chancellor Hitler personally ordered the shooting of 85 National Socialists. The act was justified as “ state emergency ”. The measure of the Reich government was legitimized by enactment of law. As a result, the executions were no longer criminal offenses worthy of sanction and were therefore not prosecuted as such. The contemporary doctrine of constitutional law took the view that the Führer had all-encompassing leadership power and was the first judge of his people. The Reichstag ultimately decided on Hitler's legal status, which made the legal opinion expressly binding in 1942.

The special dishes

The Reich government decided to set up special courts for political crimes. The defendant's rights of defense were severely restricted for a specific purpose. The opening of the main hearing was no longer dependent on an opening resolution that had taken place and preliminary interim proceedings . Interrogation protocols were no longer kept in the main negotiations. The decisions of the special court were not subject to appeal . The judges had however planned budgetary salaried judges from the Higher Regional Court of his, in whose district the Special Court was working.

The People's Court

The People's Court was re-established for serious political crimes such as high treason and treason as well as attacks against the Reich President. The members of the People's Court were no longer recruited from the crowd of employed judges, but instead were appointed by the Reich Chancellor for five years, even if they were not properly qualified. Intermediate proceedings were also inopportune in the proceedings before the People's Court. The filing of appeals against judgments was inadmissible. The choice of defense attorney required the approval of the court.

Dismantling of basic judicial rights in criminal law

The rule of law “ No punishment without law ”, which was already contained in the Criminal Code for the North German Confederation and later guaranteed in the Weimar Constitution, was repealed. According to the National Socialist view, this principle was only the “Magna Charta of the criminal”. He lost protection against arbitrary measures and obediently employed, unwritten customary law. In the case of Marinus van der Lubbe's punishment, for example, there was a blatant breach of the constitution when the main defendant in the Reichstag arson trial was sentenced to death by the law on the imposition and execution of the death penalty, to the particular displeasure of the Dutch government .

After the fire in the Reichstag, measures involving deprivation of liberty were permitted at any time and without any special requirements. Urgent suspicions were not required for a deprivation of liberty. Hindenburg's emergency decree was taken as the legal basis for the imposition of protective custody and its execution in concentration camps of the SA, later the SS and finally state concentration camps .

From 1935 it should also be possible to punish an act which, according to the basic idea of a criminal law or according to the common sense of the people, deserves punishment. If no criminal provision was found, the act should be punished according to the law, the basic idea of which applied best to the act. The realization of a similar offense should be sufficient for a punishment, which also meant the annulment of the criminal law prohibition of analogy .

The constitutional prohibition of multiple punishments, which was not included in the Weimar Constitution, was also abolished. If a sentence was declared served by the People's Court for pre-trial detention, or if a defendant was acquitted, the enforcement officer of the Secret State Police transferred him. The latter was able to order protective custody and carry it out by being sent to a concentration camp. Concentration camp detention was also ordered in other cases.

In cases of non-political crime, preventive detention was introduced by decree from 1936. This was regularly associated with being sent to a concentration camp. Preventive detention was neither regulated by law nor open to legal action. Within a few years many laws were passed which, by extending the death penalty as a whole, transformed criminal law into an instrument of terror. While before 1933 the death penalty was only provided for three criminal offenses, there were at least 46 offenses in 1943/1944 in which the death penalty was threatened. Overall, the maximum sentence was widely used, and the courts passed over 40,000 death sentences between 1933 and 1945.

Further tightening of criminal law were:

- from 1934 the treachery law . Prison was provided for up to five years for hateful and inflammatory remarks. The truth of what was said was no justification.

- from 1935 the Blood Protection Act . Marriages between Jews and non-Jews, as well as extramarital relations between Jews and non-Jews, were punished with imprisonment or penitentiary.

- from 1939 the Special War Criminal Law Ordinance . The death penalty was expanded to include espionage, rioting, disintegration of the military and desertion.

- from 1939 the ordinance against public pests . The death penalty has been extended to any crime in which the perpetrator has acted taking advantage of the exceptional circumstances caused by the state of war; The short name was “blackout crime”.

- from 1939 the ordinance against violent criminals. The death penalty was provided for crimes committed with the use of a weapon. This also applied to attempts and crimes that were committed before the regulation came into force, i.e. with retroactive effect.

- from 1941 the amendment of the penal code. For the first time, the type of offender is named in the Criminal Code. In the opinion of Roland Freisler , the special part of the Criminal Code should list offender types instead of descriptions of actions. The perpetrator type arouses in the reader a personality that is more lively and lasting than a description of the action.

- from 1941 the Polish Criminal Law Ordinance . The death penalty was intended as a standard penalty for anti-German statements. Singing Polish patriotic songs was considered anti-German and was subject to the regular penalty.

- From 1944 the Special War Criminal Law Ordinance 1944. For all crimes, the death penalty can be recognized if the regular range of punishment is not sufficient to atone for the common sense of the people.

Territorial expansion of the German Empire

In addition to the basic state laws, regulations on the territorial expansion of the empire also received constitutional status. With them the "unity of the German People's Empire" should be completed. This included the annexation of Austria in 1938 , the reunification with the Sudeten German territories and the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in 1939 , as well as the reunification of the Memel Land with the German Reich in the same year .

Repeal of the Weimar Constitution

The Weimar Imperial Constitution was not expressly repealed, unlike its predecessor, the Bismarckian Imperial Constitution . It was also not replaced by a systematic National Socialist body of law. For this reason it was initially claimed that the Weimar Constitution had retained its fundamental validity despite its National Socialist reform. Völkisch jurists disagreed with this, because they took the view that the Enabling Act and the Law on the Rebuilding of the Reich were the core elements of a constitution of the German Reich that was just emerging. Their legitimacy is not based on the Weimar Constitution, but on the "National Socialist Revolution".

Today's constitutional theory is based on the assumption that the essential parts of the Weimar Constitution were permanently and materially suspended. In 1933 it ceased to be the basic order of the German state.

The Weimar Constitution was not expressly repealed during the Allied occupation law. This only happened with the introduction of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany . A few rules of the Weimar Imperial Constitution continue to apply as simple constitutional law, for example the right to designate nobility. Other norms continued to apply until the Basic Law came into force, such as the transfer of civil servants' liability under state liability law to the state in accordance with Art. 131 WRV.

“Völkisches Constitutional Law” as unwritten constitutional law

The legal theory of the time assumed that the “völkisch constitutional order” in a written constitutional document , as it would have been characteristic of the 19th century, could not be exhausted. As unwritten, it is an elastic order until unity and wholeness are found in the political community of the German people. Their greatest advantage is that the basic order does not freeze. As Chancellor of the Reich, Hitler declared in a government declaration in 1933 that he ultimately wanted to conclude the rebuilding of the Reich with a constitutional charter. In 1937 he declared that a constitutional constitution that should be kept as short as possible had to be created, which the children had to learn in school. The project was not pursued; Even the participation of the aligned countries in the increasing number of statutory ordinances failed. The doctrine of constitutional law turned out to be irrelevant with regard to the actual development of national constitutional law.

Philosophical justification of the national constitutional law

The conceptual starting point of the National Socialist doctrine was not the state, but the people. The people is the union of all Germans , to which only "German bloods" belonged. All "alien" and " foreign races " were excluded. A Jew could not be a citizen because the criteria were not met. In this sense, the people were not the people of the state , but the people who were formed in their "kind" by the doctrine of uniformity. Included were the " people belonging to the people " who lived outside the state borders. The Reich should be a national state and only a means to an end. The state purpose finalized in the preservation of the "racially valuable elements" and the "preservation of the nationality". The empire as a unitary state turned away from legal principles at the national and tribal level. The Führer principle meant that “Führer” had to be categorized for all administrative levels and institutions.

The sole "bearer of the German state idea" was the NSDAP. As an alleged “class of the elite”, the NSDAP was supposed to be the “leader of the nation”. The NSDAP therefore determined the leading positions for the offices. The authorities had to work very closely with the NSDAP. In personal union, the Reichsführer of the SS was also head of the German police and Reich Minister of the Interior. Many Gauleiter were also Reich Governors. The management of the corporate organizations, i.e. the German Labor Front , the Reichsnährstand and the Legal Guardian Association and the Academy for German Law, lay in the hands of Reich leaders of the NSDAP.

Adolf Hitler was understood as the "bearer of the volkish will", as a leader. The leader should not be an organ of the state, but the embodiment of the "völkisch common will". Subordinate to the Führer were the Unterführer. Despite all the organizational diversity and overlapping areas of responsibility of the highest Reich authorities and subordinate authorities, this “Führer principle” remained intact until the end of the war. Most of Hitler's last criminal orders were obeyed.

Constitutional quality of national constitutional law

Today's constitutional theory has the type of a democratic constitution in mind, as it has established itself under constitutional law in the free, not only Western, world. Necessary elements of a constitution of this type are: respect for human dignity as a premise, the principle of popular sovereignty , the principle of the separation of powers , the inviolability of fundamental rights , judicial independence , the rule of law , the welfare state and the cultural state principle.

The national constitutional law repealed these principles, they already applied in the Weimar constitution. There were contradictions, because the national constitutional law did not serve to limit state power, but to expand it, and it was based on the relationship of a follower to the leader; all others did not participate in the law. The national constitutional law formed the polar opposite of a legal system and led to the disregard of all traditional values up to total nihilism . The right of the Nazi state was injustice in the sense of the negation of any normative binding. According to modern constitutional doctrine, the basic constitutional regulations, which were referred to as national constitutional law, have no constitutional properties.

The repeal of the national constitutional law after the Second World War

After Hitler's suicide on 30 April 1945 which ended World War II in Europe with the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on 8 May 1945. On 23 May 1945, Hitler was testamentary used managing national government with Karl Doenitz arrested as President.

At the Potsdam Conference from July 17 to August 2, 1945, the heads of government of the three victorious powers agreed that all those Nazi laws which formed the basis for the Nazi regime or which made discrimination based on race, religion or political conviction possible should be abolished . With the control council laws , in particular the control council law No. 1 concerning the repeal of Nazi law of September 20, 1945, the following were repealed: the legislative competence for the Reich government, the impeachment of Jewish officials, the criminal law by analogy, the one-party state, the discrimination against Jews in marriage law and citizenship law. The NSDAP was banned; the People's Court and the special courts were abolished. Although the National Socialist rule was based on the denial of basic rights, the Allied Control Council did not restore the basic rights of the Weimar constitution. On the British side, it was feared that fundamental rights such as freedom of speech and the press could endanger the Allied occupying power and make denazification more difficult.

German constitutional law since 1949

With the entry into force of the Basic Law (GG), the völkisch constitution was visibly abandoned. In a conscious departure from National Socialist law, the GG standardizes a free and democratic basic order which, according to the Federal Constitutional Court, "represents a rule of law based on the rule of law on the basis of the self-determination of the people according to the will of the respective majority and freedom and equality, with the exclusion of any violence and arbitrary rule" .

In the neo-Nazi milieu , which stands for the resumption and dissemination of National Socialist ideas, these principles , which are undisputed in jurisprudence , are denied, for example by the so-called Reich Citizens' Movement or the National Democratic Party of Germany . Since its foundation in 1964, the NPD has programmatically represented a nationalist nationalism and, in accordance with its goals and the behavior of its supporters, strives to eliminate the free democratic basic order. In 2011, a former Lower Saxony municipal mandate holder even demanded the reinstatement of the constitution and laws of the German Reich in force on May 23, 1945 to "restore the German Reich's ability to act as a nation-state under international law ."

literature

- Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde (Ed.): Constitutional law and constitutional law in the Third Reich . CF Müller, Heidelberg 1985.

- Martin Broszat : The State of Hitler . 15th edition, Munich 2000.

- Udo Di Fabio : The Weimar Constitution. Departure and failure . Munich 2018.

- Horst Dreier : The German constitutional law doctrine in the time of National Socialism. First report at the conference of the Association of German Constitutional Law Teachers in Leipzig from October 4 to 6, 2000. Berlin / New York 2001, p. 9 ff.

- Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth : Constitutional history . 14th edition, Munich 2015.

- Rolf Grawert : The National Socialist Rule . In: Josef Isensee / Paul Kirchhof : Handbook of the constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany . Volume I: Historical Foundations , 3rd Edition, Heidelberg 2003.

- Peter Häberle : Constitutional Studies as Cultural Studies . 2nd edition, Berlin 1998.

- Jörg Haverkate : Verfassungslehre: Constitution as a reciprocal order . Munich 1998.

- Adolf Laufs : Legal developments in Germany . 6th edition, Berlin 2006.

- Diemut Majer : Foundations of the National Socialist Legal System. Leader principle, special law, unity party . Stuttgart / Berlin / Cologne / Mainz 1987.

- Walter Pauly : The German constitutional law doctrine in the time of National Socialism. Second report at the conference of the Association of German Constitutional Law Teachers in Leipzig from October 4 to 6, 2000. Berlin / New York 2001, pp. 73 ff.

- Dieter Rebentisch : The Führer State and Administration in the Second World War. Constitutional development and administrative policy 1939–1945 . Stuttgart 1989.

- Klaus Stern : The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V. The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000.

- Michael Stolleis : History of Public Law in Germany. Third volume. Constitutional and administrative law studies in the republic and dictatorship 1914–1945 . Munich 1999.

- Michael Stolleis: National Socialist Law . In: Concise dictionary on German legal history . 2nd edition, Berlin 2016, Sp. 1806-1824.

Remarks

- ^ Dieter Rebentisch: Führer State and Administration in World War II. Constitutional development and administrative policy 1939–1945 . Stuttgart 1989, p. 96.

- ↑ Klaus Stern : The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 789 f.

- ↑ See Constitutional Laws of the German Reich (1933–1945) , collection of links on verfassungen.de, accessed on June 4, 2019.

- ↑ Provisional law for the alignment of the states with the Reich of March 31, 1933, RGBl. I p. 153.

- ↑ Second law for the alignment of the states with the Reich of 7.4.1933, RGBl. I p. 173.

- ^ Law against the formation of new parties of July 14, 1933, RGBl. I p. 479.

- ↑ Law to ensure the unity of party and state of December 1, 1933, RGBl. I p. 1016.

- ↑ a b c d Law on the Rebuilding of the Reich of January 30, 1934, RGBl. I p. 75.

- ↑ The German municipal code of January 30, 1935, RGBl. I pp. 49-64.

- ↑ Reichsstatthalter Act of 30.01.1935, RGBl. I pp. 65-66.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 812 f.

- ^ Ordinance of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State of February 28, 1933, RGBl. I p. 83.

- ↑ a b c d e Uwe Wesel : History of the law. From the early forms to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 978-3-406-54716-4 , Rn. 296.

- ↑ Law to remedy the distress of people and empire of March 24, 1933, RGBl. I p. 141.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth : Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 334.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 305.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law. Munich 2000, p. 794 f.

- ↑ Section 7 of the Act on the Secret State Police of February 10, 1936, Preußische Gesetzessammlung 1936, p. 21 [22].

- ^ Rolf Grawert: Die Nationalozialistische Herrschaft , in: Josef Isensee / Paul Kirchhof : Handbook of the State Law of the Federal Republic of Germany , Vol. I: Historical Foundations , 3rd Edition, Heidelberg 2003, p. 243.

- ^ Mario Wenzel: Germanic master race. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Vol. 3: Enmity against Jews in the past and present. Saur, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-598-24074-4 , p. 107.

- ↑ Diemut Majer: Foundations of the National Socialist Legal System . Stuttgart [u. a.] 1987, p. 157.

- ↑ Horst Dreier : The German constitutional law doctrine in the time of National Socialism. First report at the conference of the Association of German Constitutional Law Teachers in Leipzig from October 4 to 6, 2000. Berlin / New York 2001, p. 35.

- ↑ Kai Henning / Josef Keller: The legal position of the Jews , in: Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde (Ed.): Constitutional law and constitutional law in the Third Reich . Heidelberg, 1985, pp. 191 ff. [195].

- ↑ Diemut Majer: Foundations of the National Socialist Legal System . Stuttgart [u. a.] 1987, p. 159.

- ↑ Diemut Majer: Foundations of the National Socialist Legal System . Stuttgart [u. a.] 1987, p. 161.

- ^ Rolf Grawert: Die Nationalozialistische Herrschaft , in: Josef Isensee / Paul Kirchhof: Handbook of the State Law of the Federal Republic of Germany , Vol. I: Historical Foundations , 3rd Edition, Heidelberg 2003, p. 243.

- ↑ Diemut Majer: Foundations of the National Socialist Legal System . Stuttgart [u. a.] 1987, p. 148.

- ↑ Diemut Majer: Foundations of the National Socialist Legal System . Stuttgart [u. a.] 1987, p. 149.

- ↑ Diemut Majer: Foundations of the National Socialist Legal System . Stuttgart [u. a.] 1987, p. 151.

- ^ A b Walter Pauly : The German doctrine of constitutional law in the time of National Socialism. Second report at the conference of the Association of German Constitutional Law Teachers in Leipzig from October 4 to 6, 2000. Berlin / New York 2001, p. 95.

- ↑ Diemut Majer: Foundations of the National Socialist Legal System . Stuttgart [u. a.] 1987, p. 150.

- ^ Enabling Act of March 24, 1933.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 306.

- ↑ Leader's decree on government legislation of May 10, 1943, RGBl. I p. 295.

- ↑ Carl Schmitt: State, Movement, People . Hamburg 1933, p. 6.

- ↑ RGBl. I, p. 153.

- ↑ Second law for the alignment of the states with the Reich of 7 April 1933, RGBl. I p. 173

- ↑ a b c Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 787.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 788.

- ↑ Horst Dreier: The German constitutional law doctrine in the time of National Socialism. First report at the conference of the Association of German Constitutional Law Teachers in Leipzig from October 4 to 6, 2000. Berlin / New York 2001, pp. 9 ff. [28].

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The State of Hitler . 15th edition, Munich 2000, p. 151.

- ↑ Rolf Grawert: Die Nationalozialistische Herrschaft , in: Josef Isensee / Paul Kirchhof: Handbuch des Staatsrechts der Bundes Republik Deutschland , Vol. I: Historical Foundations , 3rd Edition, Heidelberg 2003, p. 242.

- ↑ Michael Wildt : The first 100 days of Hitler's government , Zeitgeschichte-online , July 5, 2017.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 311.

- ↑ Art. 4 of the law on the rebuilding of the empire of January 30, 1934, RGBl. I p. 75.

- ↑ Hubert Rottleuthner : The constitutional situation in the »Third Reich«. Destruction of the constitution during the Nazi dictatorship , website of the DHM , no year.

- ^ Decree of the Reich President on the provisional regulation of the flag raising of March 12th, 1933, RGBl. I p. 103.

- ↑ Art. 2 of the Reichsflaggengesetz of September 15, 1935, RGBl. I p. 1145.

- ↑ RGBl. I, p. 175.

- ^ Peter Longerich: Politics of Destruction. An overall presentation of the National Socialist persecution of the Jews . Munich 1998, ISBN 3-492-03755-0 , pp. 42 and 600.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V. The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 795.

- ↑ Law for the Prevention of Hereditary Offspring of July 14, 1933, RGBl. I p. 529.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 322.

- ^ Reich Citizenship Law of September 15, 1935, RGBl. I p. 1146.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 325.

- ^ First ordinance to the Reich Citizenship Law of November 14, 1935, RGBl. I p. 1333.

- ↑ Law for the protection of German blood and German honor of September 15, 1935, RGBl. I p. 1146.

- ↑ Law to ensure the unity of party and state of December 1, 1933, RGBl. I p. 1016.

- ^ Law against the formation of new parties of July 14, 1933, RGBl. I p. 479.

- ↑ Law on the Head of State of the German Reich of August 1st, 1934, RGBl. I p. 737.

- ↑ Law on the swearing in of civil servants and soldiers of the Wehrmacht of August 20, 1934, RGBl. I p. 785.

- ↑ Decree of the Reich Chancellor of August 2nd, 1934 on the implementation of the law on the head of state of the German Reich of August 1st, 1934, RGBl. I p. 751.

- ↑ Alisa Schaefer: Führergewalt instead of separation of powers , in: Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde (Hrsg.): Staatsrecht und Staatsrechtslehre in the Third Reich . Heidelberg, 1985, pp. 89 ff. [95] with further reference to Ernst Rudolf Huber: Das Staatsoberhaupt des Deutschen Reiches , Journal for the entire political science 1935, pp. 202 ff. [222 f.]

- ↑ Rolf Grawert: Die Nationalozialistische Herrschaft , in: Josef Isensee / Paul Kirchhof: Handbuch des Staatsrechts der Bundes Republik Deutschland , Vol. I: Historical Foundations , 3rd Edition, Heidelberg 2003, p. 248.

- ↑ Michael Stolleis : History of Public Law in Germany , Vol. 3: Constitutional and Administrative Law Studies in the Republic and Dictatorship 1914–1945 . Munich 1999, p. 332.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 320.

- ↑ Herwig Schäfer: The legal position of the individual - From the basic rights to the national subordinate position , in: Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde (Ed.): Constitutional law and constitutional law in the Third Reich . Heidelberg, 1985, pp. 106 ff. [113].

- ↑ Uwe Wesel refers in his work History of Law. From the early forms to the present in marg. 299 (p. 502) in response to this quote from Karl Larenz: “ I do not have rights and duties as an individual, as a human being or as a bearer of an abstract, general reason ... but as a member of a community that is legally based, the national community . Only as a being living in community, as a national comrade, is the individual a concrete personality. ... Legal comrades are only those who are national comrades; People are comrades who are of German blood. This sentence could be placed at the top of our legal system in place of § 1 BGB, which expresses the legal capacity of 'every person'. "

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V. The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 824f.

- ↑ Rolf Grawert: Die Nationalozialistische Herrschaft , in: Josef Isensee / Paul Kirchhof: Handbuch des Staatsrechts der Bundesoline Republik Deutschland , Vol. I: Historische Basis , 3rd edition, Heidelberg 2003, p. 245.

- ↑ a b Uwe Wesel: History of the law: From the early forms to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2001, Rn. 298.

- ↑ Law on State Emergency Defense Measures of July 3, 1934, RGBl. I p. 529.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 315 f.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V. The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 844 f.

- ^ Resolution of the Greater German Reichstag of April 26, 1942, RGBl. I p. 247.

- ^ Ordinance of the Reich government on the formation of special courts of March 21, 1933, RGBl. I p. 136.

- ↑ Art. III of the law amending provisions of criminal law and criminal procedure of April 24, 1934, RGBl. I pp. 341-348.

- ↑ § 2 of the Criminal Code for the North German Confederation of May 31, 1870, Federal Law Gazette North German Bund 1870, p. 197.

- ↑ Art. 116 WRV

- ↑ Joachim Gernhuber: Das völkische Recht in: Otto Bachof (Ed.): Tübinger Festschrift for Eduard Kern. Tübingen 1968, p. 167 ff [170].

- ↑ Law on the imposition and execution of the death penalty of March 29, 1933, RGBl. I 1933. p. 151.

- ^ Gerhard Anschütz: The constitution of the German Reich of August 11, 1919. 14th edition Berlin 1933, reprint 1987, Art. 116. P. 584 above.

- ^ Ordinance of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State of February 28, 1933, RGBl. I p. 83 - Reichstag Fire Ordinance

- ^ Circular decree of the Reich Minister of the Interior of April 1934, Marlis Graefe, (Ed.): Sources on the history of Thuringia . 4th edition, Erfurt 2008, p. 155.

- ↑ a b c d Uwe Wesel: History of the law. From the early forms to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2001, Rn. 304.

- ↑ Section 402 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of February 1, 1977, RGBl. 1877, pp. 253-346.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 337.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: On the perversion of criminal justice in the Third Reich. Quarterly books for contemporary history 1958, p. 390 ff [399.]

- ↑ Martin Broszat: On the perversion of criminal justice in the Third Reich. Quarterly books for contemporary history 1958, pp. 390 ff [394 f.]

- ↑ Martin Broszat: On the perversion of criminal justice in the Third Reich. Quarterly books for contemporary history 1958, pp. 390 ff [397.]

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 682.

- ^ Law against insidious attacks on the state and the party and for the protection of party uniforms of December 20, 1934, RGBl. I 1934, p. 1269.

- ↑ Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor of September 15, 1935. RGBl. I 1935, p. 1146 f.

- ^ Ordinance on Special Criminal Law in War and Special Use of August 17, 1938. RGBl. I 1939, pp. 1455-1457.

- ^ Ordinance against public pests of September 5, 1939, RGBl. I 1939, p. 1679.

- ^ Ordinance against violent criminals of December 5, 1939, RGBl. I 1939 I p. 2378.

- ↑ Law amending the Reich Criminal Code of September 4, 1941, RGBl. I 1941, p. 549 f.

- ^ Bernd Mertens: Legislation in National Socialism. Tübingen 2009, p. 78.

- ^ Ordinance on the administration of criminal justice against Poland and in the incorporated eastern regions of December 4, 1941. RGBl. I, 1941 pp. 759-761.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 682.

- ^ Fifth ordinance to supplement the special war criminal law ordinance of May 5, 1944. RGBl. I, 1944 p. 32 ff.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V. The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 812 f.

- ↑ Law on the reunification of Austria with the German Reich of August 13, 1938, RGBl. I pp. 237-240.

- ↑ Law on the reunification of the Sudeten German territories with the German Empire of November 21, 1938, RGBl. I pp. 1641-1649.

- ^ Decree of the Führer and Reich Chancellor on the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia of March 16, 1939, RGBl. I pp. 485-597.

- ↑ Law on the reunification of the Memelland with the German Empire of March 23, 1939, RGBl. I p. 559 f.

- ↑ Art. 178 para. 1 WRV

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 338.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V. The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 810.

- ↑ a b c Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V. The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 811.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 338.

- ↑ Udo Di Fabio: The Weimar Constitution. Departure and failure . Munich 2018, p. 244.

- ^ Rolf Grawert: Die Nationalozialistische Herrschaft , in: Josef Isensee / Paul Kirchhof: Handbook of the constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany , Vol. I: Historical bases , 3rd edition, Heidelberg 2003, p. 227.

- ↑ Udo Di Fabio: The Weimar Constitution. Departure and failure . Munich 2018, p. 245.

- ↑ Art. 123 para. 1 GG; Art. 109 para. 3 sentence 2 WRV; Federal Court of Justice, decision of November 14, 2018, Az.XII ZB 292/15.

- ↑ Art. 34 GG

- ↑ Heinz Bonk , Steffen Detterbeck : Art. 34 , Rn. 9-12. In: Michael Sachs (Ed.): Basic Law: Comment . 7th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66886-9 .

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V. The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 812.

- ↑ Martin Broszat: The State of Hitler . 15th edition, Munich 2000, p. 361.

- ^ Dieter Rebentisch : Führer State and Administration in World War II. Constitutional development and administrative policy 1939–1945 . Stuttgart 1989, p. 96 f.

- ↑ Horst Dreier: The German constitutional law doctrine in the time of National Socialism. First report at the conference of the Association of German Constitutional Law Teachers in Leipzig from October 4 to 6, 2000. Berlin / New York 2001, p. 58.

- ↑ a b c d e Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 816.

- ↑ a b c Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 814.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 822.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 823.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 821.

- ↑ Klaus Stern: The constitutional law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume V: The historical foundations of German constitutional law . Munich 2000, p. 822.

- ^ Peter Häberle: Constitutional theory as cultural studies . 2nd edition, Berlin 1998, p. 28.

- ↑ American Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776.

- ↑ Michael Stolleis: National Socialist Law , in: Concise Dictionary of German Legal History , 2nd Edition, Berlin 2016, Sp. 1810–1824 [1808].

- ↑ Jörg Haverkate: Verfassungslehre: Constitution as a reciprocal order . Munich 1998, p. 98.

- ^ Adolf Laufs: Legal developments in Germany . 6th edition, Berlin 2006, p. 404.

- ^ Adolf Laufs: Legal developments in Germany . 6th edition, Berlin 2006, p. 411.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth: Constitutional History . 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 348 f.

- ↑ Article I, Paragraph 1, Letter a of the Control Council Act No. 1 relating to the repeal of Nazi law of September 20, 1945, Official Gazette of the Control Council in Germany p. 6; Law to remedy the distress of people and empire of March 24, 1933, RGBl. I p. 141 (Enabling Act).

- ↑ Article I, Paragraph 1, Letter b of the Control Council Act No. 1 on the repeal of Nazi law of September 20, 1945, Official Gazette of the Control Council in Germany p. 6; Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service of 7.4.1933, RGBl. I p. 175.

- ↑ Article I, Paragraph 1, Letter c of the Control Council Act No. 1 relating to the repeal of Nazi law of September 20, 1945, Official Gazette of the Control Council in Germany p. 6; Art. I of the law amending the Criminal Code of June 28, 1935, RGBl. I pp. 839-843.

- ↑ Art. I, Paragraph 1 of the Control Council Act No. 1 regarding letter e of the repeal of Nazi law of September 20, 1945, Official Gazette of the Control Council in Germany p. 6; Law against the formation of new parties of July 14, 1933, RGBl. I p. 479.

- ↑ Article I, Paragraph 1 of the Control Council Act No. 1 Letter k concerning the repeal of Nazi law of September 20, 1945, Official Gazette of the Control Council in Germany p. 6; Law for the protection of German blood and German honor of September 15, 1935, RGBl. I p. 1146.

- ↑ Art. I Para. 1 of the Control Council Act No. 1 Letter l on the repeal of Nazi law of September 20, 1945, Official Gazette of the Control Council in Germany p. 6; Reich Citizenship Act of September 15, 1935, RGBl. I p. 1146.

- ↑ Art. I, Paragraph 1 of the Control Council Act No. 2 on the dissolution and liquidation of Nazi organizations of October 10, 1945, Official Gazette of the Control Council in Germany, p. 19.

- ↑ Art. II of the Control Council Act No. 4 on the reorganization of the German judiciary of October 20, 1945 p. 26.

- ↑ Matthias Etzel: The repeal of National Socialist laws by the Allied Control Council , Tübingen 1992, p. 52.

- ↑ Federal Constitutional Court in consistent case law since BVerfGE 2, 1 (principle 2) - SRP ban

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of January 17, 2017 - 2 BvB 1/13 , Rn. 633 (NPD II).

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of January 17, 2017, Az. 2 BvB 1/13, Rn. 801 (NPD II).

- ↑ Cf. Eckhard Jesse: Staatsrecht und Staatsrechtslehre im Third Reich: After 1933 the great career , Die Zeit , November 29, 1985 (review).