Transport history of the Electorate of Saxony

The history of traffic in Saxony describes the development of state infrastructure measures in the public transport and communication sector of the state of Saxony . The period shown includes the High Middle Ages in the 15th century and the subsequent early modern period up to 1806.

overview

The penetration of the area for the establishment and consolidation of rule by a small social elite was one of the most pressing logistical problems in Europe in the Middle Ages . The feudal form of rule remained for a long time a personal association of the prince and his entourage, including the lower feudal lords . The lack of institutionalization of the state offices limited the degree of penetration of the Saxon territory by public authorities. A large part of the rooms on Saxon territory remained undeveloped and had no history. The level of technical development was low, the possibilities for overcoming great distances were few, and overall social and geographical mobility was poorly developed. There were hardly any paved roads, there were no regular transport services, and spatial mapping was only rudimentary. The bonds in space were consistently weak and irregular and by no means secured. The Via Regia and the Via Imperii were two important traffic routes that crossed the Saxon region. Traders and travelers traveled on them, bringing information, knowledge and goods. Networked places and cities were the first to form along these routes. These included cities that had grown at an early stage, such as Leipzig, Görlitz and Bautzen.

The overarching development in the early modern period from 1500 to 1800 led to technical and social progress and social differentiation in Saxony. A heterogeneous and increasingly professionally acting state civil servants and engineers were formed. In addition to the state bureaucratisation, the expansion of the state infrastructure formed the second important pillar for penetrating the Saxon territory and for establishing an orderly state rule. The tasks of the public infrastructure in the early modern period included the construction of canals , dykes , forests and roads . Today's much more extensive public services of general interest developed from the first attempts at regulation in the public infrastructure sector. Significant for this was the development of the Saxon engineering corps within the Saxon army, which carried out pioneering work in the state and helped to expand the state infrastructure. The regulation and expansion of the road network formed by far the largest and most difficult task of the state after the state survey work began.

The Saxon land peace applies as a general basis for the structural development of the state areas from the 15th century . This brought about the stabilization of a basic internal security and enabled the general mobility of the population to increase. The spatial expansion of the trade via the Via Regia and the Leipzig trade fair trade increased the need and demands of travelers for a more developed infrastructure. The court culture in Saxony developed new forms and needs for example in communications or tourism additional facilities such as restaurants or hotels being incurred.

A hindrance to the establishment of a comprehensive infrastructure in the early modern period was the limited technical knowledge of the time and the low social mobility of pre-modern society. At the time, geographical areas were barriers that were difficult to overcome. The maintenance and operation of networks and means of transfer were associated with a high level of effort and expense. The control, overview and influence over the territory by the responsible actors were limited.

Wherever a dense network of infrastructural facilities developed, the prerequisites for subsequent settlement and densification of the area were given. The possibility of a quick exchange of information about the closely staggered post lines in the 18th century promoted the networking of the places in the regional and supra-regional area considerably and brought about a sustainable growth spurt.

Individual aspects

Saxon engineering corps

The military engineers distinguished themselves for the construction of the Saxon fortresses. The main tasks of the Saxon fortresses were to block mountain passes to Bohemia and to defend the Elbe as a supply and transport route. Brandenburg and France mainly used fortresses to secure their national borders. In the 18th century Saxony still owned fortresses in Wittenberg, Pleißenburg , Königstein , Sonnenstein, Stolpen , Torgau , Senftenberg and Freiberg.

The Saxon engineers were formed in 1712 from the artillery department of the Saxon Army as an independent troop unit and thus formed the first independent engineering corps in Germany. The commander of the Corps of Engineers were to 1745 at the same time at the top of civil upper building office . The measurements carried out by the engineers largely concerned the royal estates and domains in Saxony and Poland. In addition to the surveys, the maintenance of the buildings and improvements went hand in hand; Engineer officers were permanently stationed in Poland to keep the royal estates in their structural condition. Activities also included urban planning tasks, such as when an exact survey and drawing of the suburbs of Dresden were completed for regulation in 1736. The Upper Military Building Commission was set up in 1720 to regulate the fortifications and other military buildings.

Builders: Wolf Caspar von Klengel , Christian Friedrich Erndel

Road network

The economic and social development of the modern era is characterized by increasing mobility, which has shaped the transport of goods and people over long distances. The increasing traffic made it necessary to adapt and improve the traffic routes. Saxony was connected to the European road network primarily through the Via Imperii and the Via Regia . Both were central trade routes in Europe and attracted the largest traffic flows. As the intersection of the two trade routes, Leipzig also formed the center of the Saxon route network.

The road system in the electorate was in a bad state in keeping with the times. Apart from princely instructions to improve the roads, there was no suitable official substructure that could coordinate and monitor the implementation. Many orders failed mainly due to the lack of funding. The local churches should have paid for them alone. Fixed state budgets for road construction came about much later.

Infrastructural innovations came with the registration of the state roads in a cadastre from 1691 to 1694. The first general road construction mandate from 1706 aimed to standardize the construction technology and stipulated the street width.

Systematic road construction activities did not begin in Saxony until the last third of the 18th century. In the “General Instructions to the Road Commission” of January 25, 1765, it was possible to bring about a turning point in road construction . With the road construction mandate of April 28, 1781, the organization and technical construction were regulated and responsibility for the maintenance and expansion of the most important roads was transferred to the Saxon state. The preparatory work for the pioneering road construction mandate was carried out by the Saxon cabinet minister and smelter, Detlev Carl von Einsiedel . As an entrepreneur, he had a vital interest in regulated traffic conditions as a material prerequisite for an intensified circulation of goods.

The condition of the roads improved towards the end of the 18th century, when more Chausseestrassen were built in Saxony than with a solid base and the backwardness in road construction was gradually overcome. Until then, repairs had not been made systematically. From then on, the road construction methods practiced in France were conveyed via Bohemia and Austria for use in Saxon artificial road construction.

Elbe river traffic

A large part of the trade to and from Bohemia and the North German Hanseatic cities ran over the Elbe . The electricity provided various professions with a livelihood. Skippers, fishermen and bombers , i.e. towers, received their income from the Elbe. The inhabitants of the riverside places in Saxony lived from the shipping traffic and from the quarries, which would not have been operated without the cheap possibility of removing the stones by water.

Waymarks

Up until the end of the 17th century, in Saxony and elsewhere, there was little or no information about distances or locations along the roads. The road layout was therefore hardly transparent and difficult to anticipate for non-residents.

Since 1682, wooden signposts, so-called arm pillars at junctions, have marked the Electoral Saxon route network. In the course of the second Saxon land survey from 1713, additional wooden distance markings were set up. With this they prepared the setting up of stone markings, the milestones.

According to the electoral order of 1721, the Saxon signposts should be erected at regular intervals along the main roads. The post mile pillars were erected nationwide from 1722 and indicated the road network for drivers and travelers in the course of the road. Despite difficulties in the implementation due to the resistance of the local authorities, the Saxon signpost system became a model for the other states in the empire.

The distance information carved in stone obelisks in leagues was an important symbol of a new spatial thinking that showed increasing control and hegemony over distant and remote areas of land through a state order.

Land surveys

The premodern Saxon society had no regular postal service or precise maps. People and messages moved at the same speed until the invention of telegraphy in the late 18th century. Until the Thirty Years' War only merchant goods were transported on wagons. However, people with or without messages traveled on foot or on horseback.

As a precondition for administrative and political orders, spatial knowledge in Saxony was therefore developed early and systematically. For this purpose, the spaces between the settlement points were brought into focus and the territories of the state were measured, mapped and marked out.

The first map of the Wettin lands was drawn up in 1566 by the theologian Job Magdeburg . It served only representative purposes and hung as a showpiece in the princely art chamber. The first Saxon land survey took place between 1586 and 1633. This meant that Saxony already had maps. However, these found no practical application.

In 1713 the second Saxon land surveying was started under the direction of Adam Friedrich Zürner . The aim was to create a precise postcard. Together with a number of assistants, he had surveyed the Saxon region in two decades and drew 141 large and 761 smaller topographic maps. After Zürner's death, his work was bundled and published in the Atlas Saxonicus novus . The miles sheets of Saxony are the result of the third topographical survey of the state of Saxony based on the French model, which was carried out with interruptions between 1780 and 1825. You are the third attempt to create a detailed map of Saxony and were under the direction of the Saxon military under the leadership of Friedrich Ludwig Aster , commander of the Saxon engineering corps. As a result of this triangulation, more than 400 mile sheets were created by 1806.

communication

In the early modern period, the state of the communications infrastructure in a country was an indicator of a country's stage of development. As a result, the establishment of dense communication networks was of great importance. Regular communications links and services were underdeveloped in the early modern period. News, goods and travel therefore took a long time to reach their intended purpose and were associated with a high search effort since there were no regular scheduled services.

Saxon Post

The beginnings of a regular post office in Saxony go back to around 1500. An electoral court post was set up for the communication of the prince's court. This official messenger system was not public and only limited to the group of people around the elector.

The development of the post in Saxony was mainly triggered by external influences. The general development of imperial mail was largely driven by the Holy Roman Empire and in particular the von Thurn und Taxis family , because they owned the shelf . When Emperor Charles V took office , the post rates , which were still fluctuating under Maximilian , became a permanent institution in Germany too; they were fixed on fixed roads, the post roads . With this fixation and the opening of the channels, the Post's relay system quickly became interesting for other customers, for territorial lords, merchants and magistrates. The entire west of Germany was penetrated with the messenger network of the imperial post. Independent entrepreneurs from the ranks of the townspeople built functioning postal systems against privileges at their own expense. There was lively competition for the new communication system. The attempt by the emperor to turn the postal system into a shelf and thus a monopoly of the Imperial Post Office, which had existed since 1490 , met with bitter resistance from the sovereigns. Because this would have restricted the sovereignty of the sovereigns in a sensitive area. The Saxon electors benefited from this situation because they were able to further expand their own position of power at the expense of that of the emperor. Thus, the sovereign's postal law became an extensive instrument of rule that extended to information and newspaper systems. The Saxon electors also viewed the post office as a source of income and temporarily left the management of the postal business to specialists who leased the company as a whole.

In Saxony, the messenger service of the city of Leipzig stood out as a widely networked postal facility. The Leipziger Botenanstalt also conducted correspondence on long-distance connections to Breslau , Prague , Nuremberg and Hamburg . Before the Thirty Years' War, the transformation of this institution into a state post office began and in 1613 the state post office of Saxony was officially founded, which was initially set up as a post office and later continued to do its services as a post office. Leipzig asserted itself as a traditional traffic hub against Dresden, until finally in 1693 the upper post office in Leipzig was designated as the location for the highest Saxon postal authority and was given priority over Dresden.

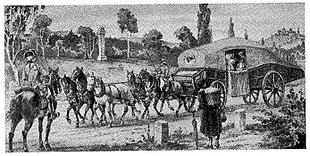

The first traveling post in Saxony started in 1660. It initially led from Leipzig to Berlin. In 1661, the Saxon postal system was finally included in a postal order as a regal shelf . The first mobile post office within Saxony was set up on August 30, 1683 and drove twice a week from Leipzig to Dresden. With this stagecoach parcels, letters, merchandise and people were transported. From then on, Saxon stagecoaches were one of the most frequented modes of transport. They were part of everyday life on the streets of Saxony. Usually the traveling mail left every major city once a week. However, the speed was only five kilometers per hour. In 1692, the second connection within Saxony began its service on the route from Leipzig to Schneeberg. On May 16, 1693, a postal and tax regulation was published in which the postal charges and the uniform operation of the postal services were regulated.

For a short time around 1700, the company was given into private hands for expansion and further investments, and decentralized, only to be nationalized again after a few years. Under the direction of the Leipzig Chief Postmaster, regional postmasters, mostly innkeepers , leased certain courses that appeared profitable in terms of their news volume. Above all, the Leipzig merchants Johann Jacob Kees the Elder and his son Johann Kees the Younger expanded the Saxon post office into a nationwide institution at the end of the 17th century. The two Saxon postmasters together created 39 further postal connections in addition to the five connections that existed in 1697. The number of post offices, mail expeditions, and post offices rose from 25 in 1690 to 144 in 1720. The post stations were mostly 18 to 27 kilometers apart.

The economic center Leipzig received a unique geometric communication structure since the 1690s, whereby the development of the postal network with carriage operation was flanked by land surveying, road signage, road construction, cartography and the publication of a course book. This led to the establishment of timetables and time regulations and the information on the exact route of the post lines in maps. Theologians from the Electorate of Saxony praised the establishment of this communication structure as a sign of God's blessing on this land. As in Kurhannover and Prussia, the remaining messenger mail was simply banned in Saxony.

In 1712, the postal system came back under the administration of the lordly chamber college . The Saxon postal network at the time was tighter than that of all other postal networks of the German territorial states. The network of expanded post roads now led traffic in all directions.

→ See also: German postal history

Periodical newsletters

The importance of cheap mass news papers was already evident in the first half of the 16th century. Due to the massive printing of leaflets that spread around the world along the busy trade routes, the Reformation was spread throughout Europe.

Another early modern innovation concerned the creation of newsletters. Georg Greflinger's Nordic Mercurius from Hamburg became the prototype of the political magazine and Hamburg became Germany's leading news city.

The first periodicals appeared in Leipzig only after the electorate of Saxony entered the Thirty Years' War . The oldest newspaper privilege in Leipzig dates back to 1633. In 1634 Moritz Pörner from Leipzig published a newspaper that appeared about four times a week.

The first daily newspaper in the world, Die Einkommenden Zeitung , was published in Leipzig from 1650 to 1652 by the printer Timotheus Ritzsch . The development of this completely new medium, which was tied to the infrastructure of the postal system, undermined the authority of the local governments and magistrates. Some of the newly founded newspapers, including the Frankfurter Postzeitung of the Frankfurter Reichspostmeister Johann von den Birghden , were not aimed at the local market, but at the national market. In the Holy Roman Empire there were around 200 newspaper companies in around eighty printing locations between 1605 and 1700.

The first edition of Acta eruditorum was published in Leipzig in 1682 . It was the first major magazine that came from Leipzig. It became necessary because new discoveries and insights in many areas of science overwhelmed book production. Around 1700, Leipzig developed into the most important printing location for magazines in Germany over several decades. Up to a third of all these papers came from Leipzig during the Enlightenment . This is also where the first magazines were created, in which opinions were presented and polemicized against other views: Here in Leipzig, Christian Thomasius laid the foundation for opinion-based journalism with the monthly discussions (published 1688 to 1690). Leipzig remained the most important German magazine location for decades. In the first decades of the 18th century, around a third of German magazines appeared in Leipzig. These included important journals such as the historical-critical journal Talks in dem Reiche der Todten by David Faßmann or the moral journal Die Vernutenigen Tadlerinnen by Johann Christoph Gottsched , both belonging to the genre of moral weeklies .

The newspaper leaseholder in Kursachsen was given the task of selling all domestic and foreign newspapers in the Electorate and was forbidden from selling newspapers by private individuals or postal officials. This was the first newspaper distribution monopoly.

Consequences

The expansion of the communication and transport infrastructure changed the way people thought about space and time at the time. Sequences of movement accelerated, space shrank and areas that otherwise remained in the darkness of lack of tradition were integrated into a transmission network and connected to the centers.

See also

literature

- Wolfgang Behringer: The world's timetable. Notes on the beginnings of the European transport revolution. In: Hans-Liudger Dienel, Helmuth Trischler (Hrsg.): History of the future of traffic. Traffic concepts from the early modern era to the 21st century (= contributions to historical traffic research. Volume 1). Campus, Frankfurt a. M. 1997.

- Origin and development of metropolises, publications of the interdisciplinary working group Urban Culture Research IAS, Volume 4, 4th Symposium June 20th - 23rd, 1996 Bonn, Aachen 2002, edited by Michael Jansen and Bernd Roeck.

- Winfried Müller, Swen Steinberg: People on the move - The Via Regia and its actors, essays on the 3rd Saxon State Exhibition, published on behalf of the Dresden State Art Collections, Sandstein Verlag, Görlitz 2011.

- Hans-Jürgen Teuteberg, Cornelius Neutsch: From the wing telegraph to the Internet: History of modern telecommunications, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, 1998, quarterly for social and economic history: Supplements No. 147, ISBN 3-515-07414-7 .

- Karin Zachmann: Mercantilism in Electoral Saxony. State economic policy with a production-centered approach. In: Günter Bayerl, Wolfhard Weber: Social history of technology. Ulrich Troitzsch on his 60th birthday. Waxmann Verlag, Münster 1998.

- Collective of authors (head of Eberhard Stimmel): Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen , Transpress VEB Verlag for Transport, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-344-00264-3 .

- Post pillars and milestones . Published by the research group Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen e. V. Dresden / Grillenburg (City of Tharandt). 3rd revised edition, Schütze-Engler-Weber Verlag GbR, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-936203-09-7 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Winfried Müller , Swen Steinberg: People on the move - The Via Regia and its actors, essays on the 3rd Saxon State Exhibition, published on behalf of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Sandstein Verlag, Görlitz 2011, in: Ralf Pulla: Tidied up and labeled: Kursächsische Postmeister und Cartographers in the Augustan Age (pp. 125–132), p. 131.

- ↑ Winfried Müller , Swen Steinberg: People on the move - The Via Regia and its actors, essays on the 3rd Saxon State Exhibition, published on behalf of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Sandstein Verlag, Görlitz 2011, in: Uwe Fraunholz: Erbauen und Destören: Sächsische Ingenieur- Officers and builders at the via regia in the Baroque age (pp. 114–124) , p. 122.

- ^ Karin Zachmann: Kursächsischer Merkantilismus. State economic policy with a production-centered approach. In: Günter Bayerl, Wolfhard Weber: Social history of technology. Ulrich Troitzsch on his 60th birthday. Waxmann Verlag, Münster 1998, p. 129.

- ↑ Winfried Müller , Swen Steinberg: People on the move - The Via Regia and its actors, essays on the 3rd Saxon State Exhibition, published on behalf of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Sandstein Verlag, Görlitz 2011, in: Ralf Pulla: Tidied up and labeled: Kursächsische Postmeister und Cartographers in the Augustan Age (pp. 125–132) , p. 130.

- ↑ Wolfgang Behringer : The timetable of the world. Notes on the beginnings of the European transport revolution. In: Hans-Liudger Dienel , Helmuth Trischler (Hrsg.): History of the future of traffic. Traffic concepts from the early modern era to the 21st century (= contributions to historical traffic research. Volume 1). Campus, Frankfurt a. M. 1997, pp. 40-57, here: p. 49.

- ↑ Winfried Müller , Swen Steinberg: People on the move - The Via Regia and its actors, essays on the 3rd Saxon State Exhibition, published on behalf of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Sandstein Verlag, Görlitz 2011, in: Ralf Pulla: Tidied up and labeled: Kursächsische Postmeister und Cartographers in the Augustan Age (pp. 125–132) , p. 131.

- ↑ Winfried Müller , Swen Steinberg: People on the move - The Via Regia and its actors, essays on the 3rd Saxon State Exhibition, published on behalf of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Sandstein Verlag, Görlitz 2011, in: Ralf Pulla: Tidied up and labeled: Kursächsische Postmeister und Cartographers in the Augustan Age (pp. 125–132), p. 125.

- ↑ Winfried Müller , Swen Steinberg: People on the move - The Via Regia and its actors, essays on the 3rd Saxon State Exhibition, published on behalf of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Sandstein Verlag, Görlitz 2011, in: Ralf Pulla: Tidied up and labeled: Kursächsische Postmeister und Cartographers in the Augustan Age (pp. 125–132), p. 127.

- ↑ Winfried Müller , Swen Steinberg: People on the move - The Via Regia and its actors, essays on the 3rd Saxon State Exhibition, published on behalf of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Sandstein Verlag, Görlitz 2011, in: Uwe Fraunholz: Erbauen und Destören: Sächsische Ingenieur- Officers and builders on the via regia in the Baroque age (pp. 114–124), p. 123.

- ^ Origin and development of metropolises, publications of the interdisciplinary working group Urban Culture Research IAS, Volume 4, 4th Symposium June 20-23, 1996 Bonn, Aachen 2002, edited by Michael Jansen and Bernd Roeck, Chapter Wolfgang Behringer: Infrastructure development as a criterion for central locality in the early modern period Germany (pp. 69–76), p. 69.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Teuteberg , Cornelius Neutsch: Vom Flügeltelegraphen zum Internet: History of modern telecommunications, Franz Steiner Verlag , Stuttgart, 1998, quarterly for social and economic history: Supplements No. 147, ISBN 3-515-07414-7 , chapter: Karl Otto Scherner: The design of German telegraph law since the 19th century, pp. 132–162, p. 133.

- ↑ Winfried Müller , Swen Steinberg: People on the move - The Via Regia and its actors, essays on the 3rd Saxon State Exhibition, published on behalf of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Sandstein Verlag, Görlitz 2011, in: Ralf Pulla: Tidied up and labeled: Kursächsische Postmeister und Cartographers in the Augustan Age (pp. 125–132), p. 125

- ^ Origin and development of metropolises, publications of the interdisciplinary working group Urban Culture Research IAS, Volume 4, 4th Symposium June 20-23, 1996 Bonn, Aachen 2002, edited by Michael Jansen and Bernd Roeck, Chapter Wolfgang Behringer: Infrastructure development as a criterion for central locality in the early modern period Germany (pp. 69–76), p. 74.

- ↑ Winfried Müller , Swen Steinberg: People on the move - The Via Regia and its actors, essays on the 3rd Saxon State Exhibition, published on behalf of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Sandstein Verlag, Görlitz 2011, in: Ralf Pulla: Tidied up and labeled: Kursächsische Postmeister und Cartographers in the Augustan Age (pp. 125–132), p. 126.

- ↑ https://www.historicum.net/medien-und-kommunikation/themen/artikel/zeitung/