Saxon postal mileage column

An electoral Saxon Postmeilensäule , colloquially Saxon Postmeilensäule or only Post column called, is a milestone except one, the distances and walking times eighth hour indicating exactly. The design of the stones varies depending on the distance they represent, they can be in the shape of an obelisk , an ancient herm or a stele . The model was based on Roman mile pillars , from which the incorrect designation as a pillar was derived. The Saxon Chief Postal Director Paul Vermehren arranged for it to be drawn up according to official distance determinations, the results of which are recorded as information in hours on the post-mile pillars made of carved natural stone.

The Saxon postal mile pillars were set up during the reign of August the Strong and his successor on all important post and trade routes and in almost all cities of the Electorate of Saxony to indicate official distances. This should create the basis for a uniform calculation of postal charges . Since the Electorate of Saxony was much larger than today's state of Saxony , such pillars can also be found in Thuringia , Brandenburg , Saxony-Anhalt and Poland .

Locations and images of the milestones still preserved or restored are listed in the gallery of the Saxon post mile pillars . In Saxony, the Saxon post mile columns are listed as a whole, which also includes replicas and remnants of these technical monuments that are true to the original.

precursor

In 1695, the Saxon postmaster Ludwig Wilhelm proposed a systematic survey with wooden pillars set up at regular intervals for the road from Leipzig to Dresden . Elector August the Strong thereupon ordered on June 18, 1695, “ that certain mileage owls be set ”. He had the conductor Heinrich Niedhart commissioned with it. The Electoral Saxon forest masters should instruct the wood for the pillars and the administrators of the Electoral Saxon authorities should take care of the erection of the pillars.

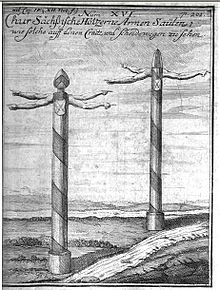

Furthermore, so-called arm pillars or arm pillars were widespread as signposts on streets in Saxony before 1700 . These pillars consisted of a wooden post with directional indicators in the form of human arms with hands at the top. Since the wood rotten quickly due to permanent exposure to moisture, numerous pillars overturned a few years after they were erected and were unusable.

The erection of the post mile pillars in the Electorate of Saxony was not a singular phenomenon. A number of countries are known from history in which such columns or stones with distance information on roads were erected.

Land survey by Zürner

The cartographic work of Pastor Adam Friedrich Zürner from Skassa formed the basis for the introduction of the Saxon post mile columns . Zürner had made a map of Grossenhain , through which August the Strong noticed him. After further cartographic work, the elector gave him the order on April 12th, 1713: " To bring offices and their lordships, manors, towns, villages and the like into mappas geographicas ". This meant the topographical recording of the Electoral Saxon areas. In addition to the heartland, they included the electoral Saxon parts of the counties of Henneberg and Mansfeld , the Schönburger Lande, the areas of the Albertine branch lines Saxony-Merseburg , Saxony-Weißenfels and Saxony-Zeitz as well as the two Lusatia .

The resulting map material remained largely secret for several decades for military reasons. The Elector only had the result of the expansion of the surveying assignment carried out a few weeks later - the creation of an improved postal map - published. The “ Chur-Sächsische Post-Charte ”, published for the first time in 1718 , remained in use with subsequent editions until the 19th century.

Since the distance information at that time was often based on inaccurate estimates, Zürner had to redetermine the distances or check the existing data. For this purpose, he constructed a measuring vehicle in the form of a travel baggage cart from the Electoral Saxony region. The rear wheel of the car with the circumference of a Dresden rod (4,531 m) passed each revolution on to a counter in the car by means of a chain . Zürner's assistants used a measuring cart for routes that were not suitable for a carriage, which also measured the distance by turning the wheel and was carried as the so-called fifth wheel on the cart in a case on the measurement cart . Both methods made it possible to measure the roads very precisely.

Another problem was the different units of measurement . In the electorate there were different mile measures at that time . For the sake of standardization, the Kursächsische Postmeile (1 mile = 2 hours of travel = 2000 Dresden rods = 9.062 kilometers) was introduced on March 17, 1722 . Zürner used the hour, which corresponded to half a mile, to indicate the distance on the distance columns.

The measurement runs usually began in Leipzig or Dresden , with the counter at the respective post office being set to zero. That is why there was talk of a Leipzig or Dresden distance. On such a journey, the surveyor's assistant had to drive in a numbered wooden stake every quarter of a mile and dig a hole next to it. The excavated material was then used to secure the wooden stake. The owner of the property was responsible for protecting the surveying post.

In some cases, the measurements were also continued outside the electorate. Wherever Saxon territory was interrupted by other areas of rule, measurements were also carried out on roads on which the Saxon post office operated with the owner's permission.

Land surveying turned out to be particularly difficult in Upper Lusatia , as the stands there tried to prevent Zürner's activity. Only on June 29, 1723, Zürner was able to begin surveying Upper and Lower Lusatia . The surveying work on the main roads in the country was completed in 1733.

Erecting the pillars

On September 19, 1721, the electoral order was issued to the offices of the cities of Dresden, Meißen and Grossenhain to erect stone post mile pillars. On November 1, 1721, the order was extended to the entire country. On the same day, the responsible state authority issued the general ordinance for the “ setting of the stone post pillars ” and the order that the landowners of the locations intended for the installation should assume the costs. A separate instruction was issued for Upper Lusatia on November 24, 1721.

Zürner, whom August the Strong commissioned by decree on December 14, 1721, worked out which pillars should be set in detail . Zürner stipulated that a large distance column had to be erected directly in front of the city gates, a quarter mile column every quarter mile, a half mile column every half miles and a full mile column every miles. While in the Electoral Saxon part of the county of Henneberg cast iron columns were to be erected instead of the stone pillars, not a single column was erected in the Electoral Saxon part of the County of Mansfeld .

Originally , around 300 distance columns and around 1200 street columns were set between 1722 and 1823, including replacement columns. Around 200 of these have survived, at least in part, or have been reconstructed true to the original, and after 1990 a large number of them have been reproduced.

Today, the old Dresden-Teplitzer Poststrasse in its Saxon section is considered to be the most complete historical traffic connection with preserved post mile columns.

The material used for the pillars in Saxony is varied and represents the main building stones of the state, which are also reflected as architecture-defining building materials in the Saxon architectural landscape. The Elbe sandstone from several extraction sites in Saxon Switzerland and in the area of the Tharandt Forest was used for most of the objects . Frequent applications are also documented with the Rochlitzer porphyry in central Saxony or the Lausitz granite in eastern Saxony. In the Chemnitz area, Hilbersdorf porphyry tuff is added as column material, which was obtained from Hilbersdorf and Flöha . In the Upper Ore Mountains and Vogtland, pillars made of granites from these areas have been erected, for example from Wiesa granite, granite from the Greifenstein area , Schwarzenberg granite, Kirchberg granite or Bad Brambach granite of the "Fichtelgebirge" type. The problem of differentiated weathering behavior associated with this variety of rocks turns out to be a monument conservation challenge in some cases . For this reason, too, numerous pillars no longer exist.

Resistances

Both the costs and the responsibility for setting up the pillars had to be borne by the local authorities, which is why the measures did not meet with unanimous approval in the country. Because the performance of the cities was very different depending on the commercial structure and size, the financial burdens hit the places very differently. Regardless of their size, they often had a similar number of city gates and therefore a comparable number of pillars. Often there were three to five goals. In 1722, the Saxon state parliament asked the elector to forego the costly project, which aroused opposition from many city councils and landowners across the country. Numerous cities tried to ignore or delay the decree.

To implement the instructions, the elector had to take tough measures and threatened disciplinary measures with an "order" of July 24, 1722 for negligence, default or damage to the pillars and, on September 7, 1724, again punishments for every official for missed deadlines and for every single negligence Height of 20 thalers. The gaps appeared particularly conspicuous on the streets of Central Saxony, in the area of the places Colditz , Grimma , Oschatz , Rochlitz and Waldheim , as well as the routes from these cities to Leipzig and from there to Zeitz and were the subject of public reprimands in the decree of September 7th by the elector.

In the course of this conflict, many places sought to have only one pillar set up. Zürner knew the location of many small communities very well. In the course of implementing the project, he began to support the cities in their endeavors and advocated the elector's approval. In many cases, this was granted in accordance with the requests of the cities. Wooden arm pillars were erected on the national connecting roads or existing objects were repaired. After 1727, the practice of one pillar per city had prevailed in many cases.

Since the order of September 19, 1721 was already accompanied by a 24-point memorandum with a list of the advantages of the ordinance, problems seem to have been expected from the start. The memorandum named as advantages of the land survey, for example, that the payment of "bothen, relay, guards and other carriages" would be verifiable and that the prices could no longer be set arbitrarily, that there would be fewer complaints from travelers about excessively high fees being paid At that time, courts and higher authorities were busy to a large extent, and that travel and transport times would for the first time be precisely determined by the measurement. Another argument was made that roads are more recognizable in winter and at night.

The resistance against the post mile pillars in Upper Lusatia was particularly strong . The city councils of Bautzen and Görlitz refused in 1723 to even receive Zürner on this matter. It was not until March 31, 1724 that the Upper Lusatian estates declared themselves ready to obey the instructions.

Since individual columns were damaged or even overturned, an order from 1724 stipulated imprisonment and other “severe and exemplary punishments” for such acts .

Due to the sustained resistance, the Saxon state parliament was finally able to prevail against the elector on April 12, 1728 with the decision to erect the pillars only on main and post roads.

Appearance

It is unclear to what extent August the Strong himself was involved in developing the designs for the columns. The appearance of the columns, which ultimately followed baroque, antique models is associated with the then Oberlandesbaumeister Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann .

Distance column

The large distance column consists of seven parts. The base is formed by the plinth, pedestal and the pedestal crown. The superstructure consists of an intermediate plate (shaft base), shaft, coat of arms and attachment (tip). The pillars have an average height of 8 cubits (4.53 meters) and rest on a foundation half a cubit high. The individual parts of the column are held together by means of iron pins cast in lead . On the shaft of the column is the direction of destination, written in Fraktur at Zürner's instructions and created using distance tables that were drawn up for each city. Some of the routes interrupted by borders are indicated by a gr or a horizontal line. Part of the inscription is a post horn attached to all four sides on all pillars , which stood as a symbol of the state's postal sovereignty. The coat of arms of the Electorate of Saxony with a gold-plated crown and the Polish royal crown with the royal-Polish-Lithuanian coat of arms are attached across the corner .

The pillars originally erected in front of the city gate usually bore the distance information on two sides and the city name of the destination on the other two. Columns erected later directly on the market square, however, contained the distance information on all four sides.

Full mile column

The all-mile column was erected to mark every full mile on Poststrasse. It is about 3.75 meters high and resembles the large distance column in its shape. However, it is slimmer and has no coat of arms . The lettering is attached on two sides so that the traveler could read it in the direction of travel. On the street side is the so-called row number with which all street pillars and stones are numbered. Since a number is assigned to each quarter mile, each full mile column has a row number that can be divided by four.

Half mile pillar

The half-mile pillar, also known as the hourly pillar, since the hour was a distance of half a mile, has a low base and an overlying shaft that tapers from top to bottom. A roof-shaped beveled plate forms the upper end. The total height is about 3 meters. It bears the same inscriptions as the all-mile column. The herm-like design of the post half mile column meant that only a few of this type are preserved today. The row number is always even, but not divisible by four.

Quarter milestone

The quarter milestone rests on a low base and consists of a rectangular plate or stele. The total height is about 1.7 meters. Inscriptions were not provided for these columns, they only bear the monogram "AR", a post horn , the year of manufacture and, on the narrow side facing the street, the always odd row number.

Distance column on the market in Neustadt in Saxony

All-mile column on the Old Dresden-Teplitzer Poststrasse near Breitenau

Half mile pillar in Markneukirchen

Quarter milestone in Bad Lausick

Coat of arms of the Electorate of Saxony on the distance column in Geringswalde

successor

In the Kingdom of Saxony in connection with the work of were Normalaichungscommission and the related lead works by Albert Christian Weinlig and Julius Ambrosius Hülße the preparations for the introduction of the metric system completed. These also provided for a transition phase for old units of measurement. At almost the same time, these efforts took place at the German Confederation level . After a new survey in 1858, a new system of milestones was created between 1859 and 1865 - the Royal Saxon milestones in the form of station, full mile, half mile, branch and border crossing stones - (from 1840: 1 mile = 7.5 km) . After the introduction of the metric system around 1900, these were partly redesigned into kilometer, road, corridor boundary or street keeper stones. In Saxony, the Royal Saxon milestones are listed as a whole under monument protection, which also includes replicas and remnants of these technical monuments that are true to the original.

literature

- Carl Christian Schramm : Saxonia Monumentis Viarum Illustrata. - Way-wise men, arms and miles pillars . Wittenberg 1727.

- Eberhard Stimmel : Saxon postal mile columns - Bibliography . Published by the research group Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen e. V. Verlag für Bauwesen, Berlin 1988.

- Collective of authors: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . Published by the research group Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen e. V. transpress publishing house for transport, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-344-00264-3 .

- Gustav Adolf Kuhfahl : The Saxon post mile columns of August the Strong… . Verlag des Landesverein Sächsischer Heimatschutz, Dresden 1930.

- Hans-Heinrich Stölzel : Existing post-mile columns and remnants of the Saxon region. In: Sächsische Heimatblätter . Volume 6, 1971, pp. 261-271.

- Post pillars and milestones . Published by the research group Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen e. V. Dresden / Grillenburg (City of Tharandt). 3rd revised edition, Schütze-Engler-Weber Verlag GbR, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-936203-09-7 .

Web links

- Gallery of the Saxon post mile pillars

- Research group Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen e. V.

- Saxon post mile pillars

- Map of the offices of Wurzen, Eilenburg & Düben (Schenck, Amsterdam 18th century, no mention of Zürner) This map shows two of the Saxon post mile pillars created by Zürner: a half mile pillar (fallen over, with the monogram “AR”) and a standing quarter milestone.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, pp. 115-117.

- ^ O. Herrmann: Quarry industry and quarry geology . 1st edition, Berlin 1899.

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, pp. 99, 100, 121.

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, pp. 96-97.

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, p. 100.

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, p. 111.

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, pp. 95-96.

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, p. 98.

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, p. 97.

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, p. 99.

- ↑ cf. Research group Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen e. V. ( Memento from January 7, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, p. 94.

- ^ Paul Domsch: Albert Christian Weinlig. A picture of life based on family papers and files. Chemnitz 1912 (Treatises and reports by the Technical State Schools in Chemnitz, Volume 2), p. 83.

- ↑ Law and Ordinance Gazette for the Kingdom of Saxony, 1858, March 12, 1858 No. 18, Law concerning the introduction of a general national weight and some provisions on measures and weights in general .

- ↑ Author collective: Lexicon Kursächsische Postmeilensäulen . 1989, p. 143.