Battle of Worringen

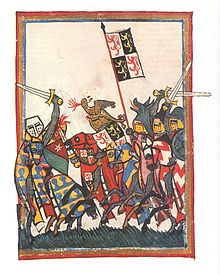

The Battle of Worringen, illustration from around 1440/50 from a manuscript of the Brabantsche Yeesten by Jan van Boendale

| date | June 5, 1288 |

|---|---|

| place | near Worringen (Fühlinger Heide) |

| output | Victory for Brabant |

| consequences | The Duke of Brabant becomes Duke of Limburg in personal union ; Power weakening of the Archbishop of Cologne |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Siegfried von Westerburg , Archbishop of Cologne

|

John I of Brabant , Duke of Brabant

|

| Commander | |

|

Siegfried von Westerburg |

John I of Brabant |

| Troop strength | |

4,200

|

4,800

|

In 1288, the Battle of Worringen was the final armed conflict in the six-year Limburg succession dispute . The main opponents of the conflict were Siegfried von Westerburg , Archbishop of Cologne , and Duke Johann I von Brabant . The outcome of the battle changed the power structure in the entire north-west of Central Europe .

The cause of the conflict

The conflict was triggered by the dispute over the succession of Irmgard, who was the only daughter of the last Duke of Limburg, Walram V and wife of Rainald von Geldern , who had brought the Duchy of Limburg to her husband after the death of her father . Associated with the sovereignty over this duchy was the title of Duke of Lower Lorraine . King Rudolf I confirmed this succession by Raynald 1282 Limburg belehnte .

Irmgard died the following year. The marriage had remained without children. In feudal law it was repeatedly disputed whether, in the event that there were no male heirs, the line of succession would be continued through the female line or through the closest male relatives. Against this background, the claim should be seen that Count Adolf V./VIII. von Berg asserted as the nephew of Walram V after Irmgard's death. In addition to him, Heinrich von Luxemburg, his brother Walram von Ligny, their cousin Walram von Valkenburg, Walram von Jülich ( provost of the Aachen Marienstifts ), his brothers Otto von Heimbach, understood each other through their descent from Duke Heinrich the Elder of Limburg († 1221) and Gerhard von Kaster, as well as his cousin Walram von Jülich-Bergheim and Dietrich von Heinsberg and his brother Johann von Heinsberg-Löwenberg as entitled to inherit. All of these applicants had agreed to make a decision on February 2, 1284 as to which of them, with the support of the others, should lay claim to the inheritance. At that point, a peaceful settlement seemed quite possible.

The long way to Worringen

Duke Johann I von Brabant could not make any claims to inheritance, unmistakably he had not only political interests, but also economic interests. A connection to Limburg could be established through the ducal dignity of Lower Lorraine , to which both the Brabant and the Limburg title went back.

The reason for the armed conflict that followed was provided by Adolf von Berg when he, realizing that he did not have sufficient funds to enforce his claim, sold it to Johann von Brabant on September 13, 1283. The Limburg vassals of Adolf refused to take the oath of homage to Johann , whereupon he and his troops invaded the Duchy of Limburg.

Siegfried von Westerburg , Archbishop of Cologne , in his capacity as sovereign of the Electorate of Cologne , could not accept the ambitions of Johann von Brabant, as he saw the increase in power that the Duchy of Limburg would give Brabant as a restriction and threat to his own position of power on the Lower Rhine recognized.

For his part, Rainald von Geldern recognized that he alone would not be able to assert himself against Johann von Brabant, and so he closed a week later on August 16, 1284 at the Vennebrucke hill (today Vinnbrück near Kempen - Tönisberg ) a military alliance with the Archbishop of Cologne directed against Brabant and Berg.

Rainald was enfeoffed with Wassenberg , which the Dukes of Limburg held in the past as a Cologne fief. The Rainald party also included Walram von Valkenburg, who was appointed by Rainald as his representative in Limburg. A complex treaty system in connection with the enfeoffment of Wassenberg bound Rainald and his allies, on the one hand, and the archbishop, on the other, tightly together.

The counties of Berg and Mark were committed to the archbishop's military success in his function as Duke of Westphalia. Count Eberhard von der Mark took the family claims of his relative Adolf von Berg to Limburg as an opportunity to put his long-pursued attempts at emancipation from the ducal power under new auspices and to put a stop to the territorial consolidation attempts of the Archbishop of Cologne in the area of his duchy. So he confronted the Archbishop as a fellow campaigner of Adolf von Berg.

The Limburg knighthood was divided: the Drost von Limburg, Kuno Snabbe von Lontzen and his entire clan of the Skavedriesch stood on the side of Rainald. Heinrich von Mulrepas from the von Geilenkirchen family had held the office of Drosten before Kuno, but had been dismissed by Rainald. This explains why the Mulrepas and von Wittem's relatives were to be found on the side of Johann von Brabant. Both parties, the Skavedriesch and the Mulrepas with that of Wittem, were parties of equal power.

The Luxembourgers had also sided with Rainald, but held back in the first year of the conflict.

The period from September 1283 to June 1288 was marked by numerous disputes that left scorched earth everywhere, but especially in the Duchy of Limburg. There were repeated front changes by individual parties involved.

In May 1288, Count Heinrich von Luxemburg moved with his army towards Cologne . On the way there, his army grew by joining numerous vassals and allies. At the end of May Heinrich met with the Count von Geldern and the other allies in Valkenburg. The next steps were discussed. In the end, Rainald sold all claims and rights to the county of Geldern to Heinrich and his brother Walram of Luxembourg for 40,000 marks Brabant denarii . When this became known to him, Duke Johann von Brabant also set out, first in the direction of Valkenburg, then to Cologne. On May 25 or 26, negotiations took place in Brühl between Johann, Count Eberhard von der Mark, Adolf von Berg and Walram von Jülich. Representatives of the city of Cologne also took part. A Landfriedensbund was negotiated, which was contractually secured on May 27 or 28 in Cologne. Cologne thus became an important base for Johann. The first goal of the community was the razing of the archbishopric castle Worringen .

Worringen was besieged from May 29 to June 5; A large contingent of troops from Cologne's citizens supported the Brabant army with siege and slingshot machines.

At the same time, the Count of Luxembourg, Siegfried von Westerburg and their allies gathered near Neuss and moved to Brauweiler . They camped there on the night of June 5, 1288.

At this point, all parties involved had reached the limit of their resilience. After the Landfriedensbund of the city of Cologne with Johann, which can also be seen in the tradition of the emancipation efforts of the citizens of Cologne from their city lord since the first conflict with Anno II in 1074, there was no other way for the archbishop either. A decisive battle, which had always been avoided on this scale in previous years, had become inevitable for everyone.

June 5, 1288 on the Fühlinger Heide

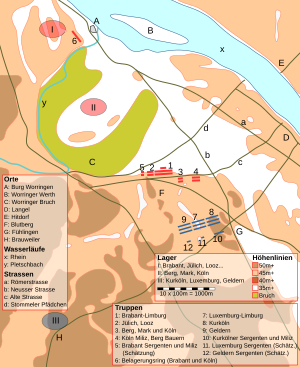

Early in the morning, after attending morning mass and having confessed, Archbishop Siegfried von Westerburg set out from his camp in Brauweiler with his army on the twelve-kilometer journey in the direction of Worringen. Johann von Brabant, informed by scouts of the approaching archbishop's army, moved towards him from Worringen and took up position on a hill southeast of the Worringer Bruch (northwest of today's Fühlingen ). The archbishop and his troops probably arrived there around 11:00 a.m. His constellations were formed west of today's Fühlingen, with the Luxembourgers taking the middle position on the archbishop's side compared to the Brabantians. The Archbishop himself stood with his Cologne troops on the right wing opposite the troops of Counts Adolf von Berg and Eberhard von der Mark, who were joined by the foot soldiers of the city of Cologne on the wing and the farmers of the Mark and Berg region. The Count of Geldern took a position on the left wing towards the riders of the Jülich and the Count of Looz, as well as the Brabant infantry, who were positioned on the outside.

Right at the beginning of the battle, the archbishop succeeded in overcoming the Bergische infantry and the Cologne militia and routed them. But the archbishop placed himself in a strategically extremely unfavorable position, which almost led to the dissolution of his formation. In the opinion of the military historian Ulrich Lehnart , this early action by the archbishop was already the decisive event that would determine the outcome of the battle. The fiercest battle raged in the middle of the two fronts between the Brabants and the Luxemburgers. First Walram von Luxemburg-Ligny, then Heinrich von Luxemburg, Heinrich von Houffalize, Heinrich's bastard brother, and his younger brother (whose name was probably Baldwin) lost their lives. This wiped out an entire generation of the House of Luxembourg.

Probably around 3:00 p.m. the knights of the Counts von Berg and von der Mark attacked the Archbishop and his troops again on the right flank with the Cologne patricians and the troops of the Bergisch farmers and the Cologne militia. Encouraged by the fiery speech of Walter Dodde and the role model of the patrician Gerhard Overstolzen , they again intervened in the fighting with all their might to compensate for their debacle of the morning. Overstolzen, armed as an armored rider, had dismounted his horse and stood at the head of the infantry on foot, later collapsed from exhaustion and died without a fight.

The way of fighting of the Bergischen farmers and the Cologne militia is described in such a way that they hit everything and everyone, no matter if enemy or friend. This was probably also due to the fact that they did not know most of the coats of arms and therefore could hardly distinguish between enemy and friend.

The archbishop soon recognized his situation as hopeless and offered Gottfried von Brabant his surrender. The infantry of the Bergisch farmers and the Cologne militia captured the archbishop's flag wagon , which caused the total collapse of the resistance of the Cologne wing. Anyone who was unable to escape was taken prisoner.

Rainald von Geldern on the left wing soon saw his situation as hopeless. While trying to escape undetected, he was taken prisoner by the Duke of Brabant. Walram von Valkenburg was the last vassal of the archbishop who left the battlefield after a fierce duel with the provost of the Aachen Marienstift. He owed it to the help of Count Arnold von Loon that he managed to escape.

The last fighting took place between the Skavedriesch and the Mulrepas, who seemed to be waging their own conflict here. Finally the still living Skavedriesch surrendered, with which all fighting was over. This should have been the case around 5:00 p.m.

The surviving knights and their horses were captured and promised ample ransom.

Most of the dead on the battlefield were disfigured beyond recognition by the horses' hooves. In addition, the corpses of the infantry were responsible for the fact that the dead could no longer be identified by their tabards. The bodies were buried in several mass graves.

Today's estimates consider it likely that around 10,000 fighters were involved in the battle. Lehnart determined around 2,300 Panzerreiter (knights) for the Brabant armed forces and around 2,800 for the Kurkölnischen. The portion of the Cologne patricians on the Brabant side is said to have consisted of about 60 armored riders.

The infantry on the Brabant side is estimated at around 2,500 men (including 500 Bergische farmers and 1,500 Cologne militia), that of the archbishopric at around 1,400.

According to sources, 1,100 fighters are said to have died on the battlefield, 700 later died from their injuries. In Cologne there are said to have been more than 700 widows after the battle. 600 fighters are said to have been buried in the mass graves.

The infantry had to accept the greatest losses. In view of the fact that medieval equestrian battles were not aimed at killing the enemy but capturing them in order to receive a ransom for his release and thus to be able to cover his own war costs, this seems realistic.

The extreme harshness with which the Bergisch farmers and the Cologne militia proceeded in their second intervention may have been the reason why many armored riders preferred to be captured by the opposing knights rather than being slain by the opposing infantry.

The effects of the battle

The outcome of the battle had significant consequences for each of the parties involved.

Archbishop Siegfried von Westerburg was a prisoner in the power of Count von Berg in the "Novum Castrum" ( Castle Burg an der Wupper ). Only through the Atonement Treaty of May 19, 1289 did he regain freedom. In the meantime the cathedral provost of Cologne, Konrad von Berg, a brother of Adolf von Berg, had taken over the government of the archbishopric. The winners of the battle had created facts that Siegfried had to approve, willy-nilly, in addition to the payment of the ransom of 12,000 marks through the atonement contract. In addition, he had to renounce his fortification rights in the Bergisches Land. Eberhard von der Mark received fortification sovereignty and Adolf von Berg his right to mint, which he had to renounce in 1279 in favor of the Archbishop.

One of the facts that have been established in the meantime was the de-fortification of the Rhine, first and foremost the razing of Worringen Castle , as well as that of the archbishopric castles of Zons and Neuenberg . This corresponded to the demands of the citizens of Cologne and Count von Berg.

Adolf von Berg granted Dusseldorf city rights on August 14, 1288 , thereby setting a further counterpoint to the previously undisputed power of the Archbishop on the Lower Rhine and thus laying the foundations for the future Bergisch royal seat . This was accompanied by the establishment of a canons' foundation . In 1322 Mülheim was also granted city rights by the Counts of Berg. Both cities, Düsseldorf and Mülheim, later developed into urban trade and economic centers. The competition between the cities of Cologne and Düsseldorf was a frequent cause of tension between them in the following years.

In Westphalia, the castles of Neu-Isenberg , Volmarstein , Limburg an der Lenne , Raffenburg and the cities of Menden , Fürstenberg and Werl were taken and mostly demolished; this corresponded to the demands and wishes of Eberhard von der Mark. Eberhard also acquired the bailiwick through the Essen monastery , which remained in the family until it went out in 1609. At the same time, the Cologne defeat marks the decline of the Cologne suzerainty over the Counts of the Mark.

Walram von Jülich conquered Zülpich with the help of the citizens of Cologne , but one cannot yet speak of territorial development here.

The developments favored the expansion of the territories of the Counts von Berg and von der Mark, while the efforts of the Archbishop to secure and expand his ducal power in Westphalia were thwarted.

After his release, Siegfried obtained papal dispensation , which released him from the observance of the concessions he had made in captivity from the point of view of the Church, but this actually did nothing. Not the process that Siegfried brought against Cologne, and not even the papal ban could change anything. In fact, the city of Cologne had already achieved the status of an imperial city in many respects , although de jure recognition would be another 200 years away.

After a respite, the Duke of Brabant had to deal with Walram von Valkenburg again militarily before he was enfeoffed with the Duchy of Limburg on September 1, 1292 by the newly elected King Adolf von Nassau . The addition of the Limburg lion into the Brabant coat of arms in the time of John II was a visible sign of the territorial dominance over Limburg . From then on it showed the Brabant (golden lion in the black field) in the first and fourth fields, the Limburg lion in the second and third fields (red lion in the white field).

reception

An important narrative source, because it is in a timely context, is the Yeeste van den Slag van Woeronc by Jan van Heelu .

Jan Frans Willems edited and commented on it in 1836. On this basis, the text was first translated into High German in 1988 by Frans W. Hellegers and published in the exhibition catalog Der Name der Freiheit .

Heelu wrote his Rymkronik for Margaret of England, daughter-in-law of Duke John I of Brabant and wife of John II of Brabant, shortly before the death of John I.

|

Slag Van Woeringen. First Boek. |

The battle of Worringen. First book. |

|

Vrouwe Margirete van Inghelant, Die seker hevet van Brabant Tshertghen Jans sone Jan, Want sie dietsche tale niet en can Daer bi willic haer ene gichte Sinden van dietschen Gedichte, Daer sie dietsch in empty moghe; Van haren sweer, den hertoghe, Sindic haer daer bi Beschreven; Want en mach niet scoenres geven Van ridderscape goote date. |

I want to give Mistress Margaret of England, who married Duke Jan von Brabant's son Jan, a present in the form of a story in German, with which she might learn this language, which she does not speak; the story is about her father-in-law, the Duke, whom I have described here; for there can be nothing more beautiful than great knightly deeds. |

Since the late Middle Ages the topic appeared on the Battle of Worringen in other sources so the Codex Manesse , in the Brabant's Yeesten and Johann Koelhoff in Cologne Chronicle .

In the 19th century, the battle of Worringen was a theme of history painting . Well-known painters who took up the subject were Nicaise de Keyser in the painting After the Battle of Worringen (1840) and Peter Janssen the Elder in the painting Walter Dodde and the Bergischen Peasants at the Battle of Worringen (1893). A recent artistic reception is in Stadterhebungsmonument of Bert Gerresheim be found in Dusseldorf. Here the horror of battle is placed at the center of a sculptural collage.

In 1893 the city of Düsseldorf renamed its Ringstrasse to Worringer Strasse . Worringer Platz has been a reminder of the battle since 1906 .

literature

- Wim Blockmans: The Battle of Worringen in the Self- Understanding of the Dutch and Belgians , in: Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte , 125/1989, pp. 99-109. ( Online version )

- Wilhelm Herchenbach , Henri Adolphe Reuland: History of the Limburg succession dispute. The battle of Worringen and the elevation of Düsseldorf to a city. Bagel, Düsseldorf 1883. ( digitized version )

-

Wilhelm Janssen , Hugo Stehkämper (Ed.): The day at Worringen June 5, 1288 , adR: Publications of the State Archives of North Rhine-Westphalia, Series C: Sources and Research , Volume 27, Düsseldorf 1988.

Note: is also published as- Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte , 124/1988, pp. 1–453. ( Online version )

- Messages from the city archive of Cologne , issue 72 ISBN 3-412-04388-5

- Jean-Louis Kupper: Duke Johann I von Brabant and the Principality of Liège before and after the Battle of Worringen , in: Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte , 125/1989, pp. 87-98. ( Online version )

- Ulrich Lehnart: The battle of Worringen 1288. Warfare in the Middle Ages. The Limburg War of Succession with special consideration of the Battle of Worringen, 5.6.1288. AFRA-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-923217-66-8 .

- Jan Müller: The Battle Of Worringen, 1288, The History and Mythology Of A Notable Event , work on obtaining the title Master of Arts in History at the University of Alberta, Alberta 1993. ( PDF file : 1.2 MB; 4. March 2006)

- Werner Schäfke (Ed.): The name of freedom, 1288–1988, aspects of Cologne history from Worringen to today. Handbook for the exhibition of the Cologne City Museum in the Josef-Haubrich-Kunsthalle Cologne, January 29, 1988 - May 1, 1988, 2 volumes, Cologne 1988.

- Vera Torunsky : Worringen 1288 - causes and consequences of a battle. Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-7927-1029-3

Web links

- Sascha Sturm: Worringen 1288 - Decision in the six-year-long conflict of the Limburg succession dispute (March 4, 2006)

- Sebastian Thelen, Christoph Wenzel: Protest , a project of the St. Ursula-Gymnasium Düsseldorf , was created as part of the German History student competition for the Federal President's Prize 2004/2005 . (March 4, 2006)

Remarks

- ↑ Memorial to the Treaty of Vinnbrück

- ↑ For the power constellation before the battle of Worringen see: Irmgard Hantsche: Atlas zur Geschichte des Niederrheins . Cartography by Harald Krähe. Bottrop / Essen: Verlag Peter Pomp, 1999 (series of publications by the Niederrhein Academy, vol. 4), p. 32f

- ↑ The “wagon with key” shown in the picture in Koelhoff's chronicle is not the archbishop's flag wagon, but the wagon of the citizens of Cologne, i.e. the adversary. See Ernst Voltmer: Standart, Carroccio, Fahnenwagen. The function of the field and rulership symbols of medieval cities using the example of the Battle of Worringen. In: Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte 124, 1988, pp. 187–209

- ↑ Internet portal Westphalian history

Coordinates: 51 ° 2 ′ 33.1 ″ N , 6 ° 53 ′ 15.6 ″ E