Fringed winged

| Fringed winged | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

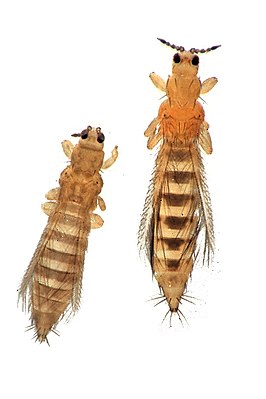

Thrips tabaci and Frankliniella occidentalis |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Thysanoptera | ||||||||||

| Haliday , 1836 | ||||||||||

| Submissions | ||||||||||

Fringed winged wings (Thysanoptera), also called thrips or bladder feet , are an order in the class of insects . They are called fringed wings because of the hair fringes on the wing edges. There are around 5,500 known species worldwide, of which around 400 are found in Central Europe and 214 in Germany.

designation

The scientific name Thysanoptera is made up of two Greek words: θύσανος thysanos "fringe" and πτερόν pteron "wing". The name "bladder feet" ( Physopoda ) refers to a flap-like structure on the end members of the feet ( arolium ). This can be everted like a balloon by increasing the pressure and is wetted with liquid by a gland, so it serves as an adhesive device on smooth surfaces.

Various names such as thunderstorm flies , thunderstorm animals, thunderstorm animals, thunderstorm worms or black flies are used in dialect or regionally for fringed wings . In ancient texts even today no longer find common vernacular names, such Putsigel , Gnidd or Gnudd in East Friesland, Hommel frogs or Flimmerchen in the Rhineland, Wettergeistlein in the Sudetenland, Kaulpanne in Flensburg.

features

Fringe-winged birds are usually between one and three millimeters in size, elongated and have strongly modified mouthparts with strongly asymmetrical mandibles, which are mainly used for pricking and sucking on plants. The adults have four narrow wings, but rarely fly actively (less than whiteflies ); many species are even wingless. The larvae are translucent and light green.

External anatomy

head

The mostly large complex eyes on the head of the fringed winged wing extend on the back (dorsal) to the ocellen hill and on the belly (ventral) to the genae . The number of ommatidia varies from species to species. Winged species also usually have three point eyes (ocelles), which are arranged on the top of the head between the complex eyes as an equilateral triangle. The ocelles lie a little higher on an ocellen hill. The tentorium is strongly regressed in most of the fringed winged birds. The flagellum antennas of most species consist of seven to eight limbs, but antennae with lengths between four and nine limbs generally occur. They can be moved in all directions thanks to their special steering on the antenna ring. In the second antenna element, the so-called pedicel which is Johnston's organ housed. The function of special sensillae on the third and fourth antenna element is still unclear.

When thrips are mouthparts asymmetrical. This is due to the fact that the right upper jaw ( mandible ) is severely receded and effectively only consists of a basic skeleton. The left mandible, on the other hand, is shaped into a piercing bristle , as with the other representatives of the Condylognatha (see external systematics). The front end of the mouthparts, the labrum , is usually asymmetrical and trapezoidal . In contrast to the mandibles and labrum, the lower jaws ( maxillae ) are symmetrical. In the fringed winged species they consist of the stipes and the lacinia, the second ark ( cardo ), has mostly receded. The Laciniae are so fused that they form a suction tube. The lip or labium is fused in the middle. The mouth opening lies behind the cibarium on the back and underside of the head cone. During the suction process, the unpaired mandible is used to poke a hole in the surface, into which the paired, stiletto-shaped laciniae are then introduced. The muscles of the cibarium act as a suction pump. Alternating with sucking, saliva is pumped into the opening.

thorax

The thorax essentially consists of two parts: the prothorax , which connects to the head cone, and the pterothorax . As the Greek word πτερόν (pteron = "wing") already indicates, the wings are attached to the latter, if they are present at the respective representative. The dorsal area of the prothorax, the pronotum , is trapezoidal to right-angled in the fringed winged birds and has bristles that are characteristic especially at the edge. The ventral side of the prothorax has many areas where the surface is made up of membranes.

The pterothorax, on the other hand, consists of several units, namely the meso- and metathorax . In species with wings, the pterothorax is particularly robust, but in species without wings it is only found in a greatly simplified manner.

wing

The expression of the wings is very different within the fringed wings. Some species have no wings, others are fully developed, and still other species have intermediate forms. The presence can also depend on gender; if one sex is wingless, it is usually the male. Only in a few species are the training or presence of the wings also variable within the species. In many species of Tubulifera, the females shear off their wings mechanically after mating. If there are wings, they are 1 to 1.2 millimeters long and have around 150 to 200 of the eponymous fringes, which give the wing a normal outline overall. Within this contour, however, only 20 to 45% are actually covered by fringes. The diameter of the fringes is 1–2 µm. The shape of the wings and the fringes enables a determination of subordination due to their different nature . The wings of the Terebrantia have veins, their surface is covered by numerous short hairs (setae) in addition to the fringes; both are absent in the Tubulifera. The fringes of the Terebrantia are attached by a base, which, thanks to its special structure, allows two positions: parallel to the wing (in rest position) and spread apart (in flight position). With the Tubulifera, on the other hand, the fringes have grown deep into the wing and have no special base, but their position cannot be adjusted. The wings are attached to the pterothorax; they have a connection at the approach that causes the wings to be coupled. In the resting position, the wings lie on the abdomen, either side by side (Terebrantia) or one above the other (Tubulifera) - they are fixed here by special bristles.

legs

As with all insects, the legs of the fringed winged wing are divided into six sections. The tarsi have only one or two limbs. The function of the partially highly specialized training of the various leg parts varies greatly from one type to another. For example, the hip ( coxa ) of the hind legs is more pronounced in many representatives and thus offers the ability to jump. Particularly noteworthy, however, are the tarsi's suction cups ( arolium ), which are responsible for the name bladder feet , and which allow the animal to literally suck on its ground.

abdomen

The abdomen is made up of eleven segments . The first segment is partially arranged under the thorax and the eleventh is strongly reduced. The genitals of the males are on the underside of the ninth segment, and of the females on the underside of the eighth segment. The tenth segment again allows a distinction to be made between the subordinates. In the Tubulifera this is tubular, whereas in the Terebrantia it is conical . The females of the Terebrantia carry a well-developed, saber-shaped ovipositor at the end of the abdomen (8th and 9th segment), which is only missing in one genus ( Uzelothrips ). When at rest it is usually placed in a recess in the abdomen. The males carry a phallus (or aedeagus ), usually with two paramers.

Internal anatomy

Nervous system

The fringed winged nervous system located in the head can be divided into the three brain areas proto-, deuto- and tritocerebrum . The antenna nerve emerges from the deutocerebrum, making this part of the brain particularly easy to find. In the thorax there are again three ganglion centers , which are named analogous to the thoracic segments pro, meso- and metathoracic ganglion. This is where the leg and wing nerves end, among other things. The nervous system in the abdomen consists mainly of two cords fused to form a ganglion cord, which lead two nerve endings into each segment.

Digestive system

Like all insects, the fringed winged intestine is made up of three parts . The food is sucked in by a suction pump (cibarial pump), in which a cavity is expanded by attaching muscles and thus negative pressure can be generated. The esophagus is relatively long and wide compared to that of aphids . At the transition to the midgut there is a valve (valva, or valvula cardiaca) made of a double-walled cylinder that protrudes into the lumen, the inner tube of which collapses under negative pressure, preventing pulp from being sucked back from the midgut when the cibarial pump is active. A second, similar valve (Valvula pylorica) prevents backflow from the rectum into the midgut. The midgut is, as is typical for insects, a simple tube, which is lined with an epithelium of cells with numerous microvilli , it lies, different for each species, in several loops, sometimes mutually differentiated sections are recognizable. The anus is located under the dorsal plate of the eleventh abdominal segment, the so-called epiproct .

Breathing and circulation

The trachea of the fringed wing consists mainly of two main strands running laterally on the back and two secondary strands running on the ventral side. The air enters through three pairs of spiracles . The heart lies in the seventh and eighth abdominal segments. From here the aorta runs relatively straight to the head. The heart is controlled by six muscle cords arranged in a star shape and the aorta is also extensively sheathed by muscles.

distribution

Since fringed- winged birds can be transported several hundred to thousands of kilometers by the wind due to their low weight as aerial plankton , they can be found all over the world except in the polar regions . The widespread distribution of numerous wingless species, including across seas, shows that, due to their low weight, wingless individuals can also occasionally be spread by air. Another factor is the trade in plants and other goods that began in the Middle Ages and is still widespread today with many species of fringed winged birds. The main focus of distribution is nevertheless in the tropics. There are currently around 400 species in Central Europe and around 5,500 worldwide. Many species are tied to special host plants .

Way of life

Flight behavior

Fringed wings reach flight speeds of about ten centimeters per second. The wing beat frequency is quite high at around 200 Hz , but lower than that of many other very small insects such as B. Mosquitoes. The animals achieve the high flapping frequency through neuron asynchronously excited flight muscles, in which the frequency of the wing flapping is not given by individual nerve impulses, but results directly from the biomechanics of the flight apparatus. Accordingly, they vary lift and propulsion less by adjusting the flap of the wing, but more by changing the flight attitude. For the very small animals, the surrounding air is a viscous (tough) medium, the wings work with Reynolds numbers of about 10 and thus an order of magnitude or more below that of large insects. The wing fringes form an almost air-impermeable surface that differs only slightly in its aerodynamic properties from a membranous wing with the same outline. The way in which the wings work in detail, in particular the generation of lift, is not yet fully understood. The flight speed, which is low in relation to typical wind speeds, means that fringed-winged birds are no longer able to maintain a different flight direction compared to the wind direction, even at a relatively low altitude above the vegetation. For migrating individuals it follows that they have no control over the direction of spread.

nutrition

Almost all Terebrantia species (around 95%), but only a small part of the Tubulifera, are plant suckers (Phytophage). Many species feed on the outer layers of the leaves , called the epidermis , and the mesophyll below . They prick individual cells with their mouthparts and suck out the liquid. The affected cells then become light and have a silvery sheen. The leaf damage is similar to that caused by spider mites . Some species induce plant galls, inside which they live and feed. Depending on the species, only individual plant species are attacked (monophagy) or a wide range of different host plants are used (polyphagia). Other species are flower visitors and feed mainly on pollen. Some fringed wings are important as pollinators. Cycads of the Macrozamia genus may rely on cycadothrips for pollinators. Known in Europe is the pollination of heather by the Heidethrips Taeniothrips ericae on the windswept Faroe Islands, where all other pollinators fail.

About 60% of Tubulifera feed on fungi, many of them on dead wood. Species from three genera ( Scolothrips , Karnyothrips and Franklinothrips ) are obligatory predators, mostly from eggs, mites, scale insects or other fringed winged birds . Predatory species such as Franklinothrips vespiformis sting the larvae and also adults of other fringed-winged birds and suck them up. Numerous other types, e.g. B. of the family Aeolothripidae, are facultative predators, also the tobacco bladder, which is feared as a pest .

Reproduction and development

Many fringed winged species reproduce at least in part by means of virgin generation , i.e. by asexual reproduction. In some species all individuals are females; Males are unknown in these (thelytocia). When determining the sex of some species, an influence of the bacterial genus Wolbachia has been proven, which parasitizes in egg cells and can suppress the development of males in many insect species. The sex of fringed winged birds is determined by haplodiploidy . As in the much better known case of the hymenoptera , unfertilized eggs always turn into males. The sex ratio has only been investigated in more detail in a few species; in some cases it has been found to be very variable and dependent on the nutritional status, population density and environmental factors. According to Lewis, the ratio between females and males in many species is around 4: 1.

For copulation , the male rises on the female's back and bends his abdomen asymmetrically on the female's ventral side to introduce his sperm into the vagina . It holds on to the front legs. The copulation lasts depending on the type from several seconds to several minutes. The females of most species make sure that only one mating is made. The female then lays twenty to several hundred eggs in (Terebrantia) or on (Tubulifera) plant tissue. For species also reproduce without fertilization, it can already ovipositor to an embryonic come.

The eggs have the shape of an ellipsoid and are relatively large compared to the size of the females. The development of the embryo takes between two and twenty days, depending on the species. The larvae resemble adult fringed winged birds in shape and way of life, but they have neither wings nor wing sheaths. The two larval stages are followed by a prepupal stage . In most species, this transformation takes place at a depth of around 20 centimeters in the ground. However, some species go into the ground to a depth of one meter, while others remain on the surface. Some species pupate in a self-made cocoon . The pre-pupal stage is followed by another pupal stage in the Terebrantia, and even two in the Tubulifera. The pupal stages probably do not correspond directly to the pupae of the holometabolic insects , but have arisen convergent .

The overwintering of the fringed winged birds in Central Europe occurs predominantly in the imaginal stage, some species are also known to overwinter larvae. The animals leave unstable habitats such as grain fields on the fly to seek out special wintering habitats. The wintering takes place in the litter, in the ground and in crevices and cracks, e.g. B. in tree bark. Animals looking for a place to hide prefer narrow crevices and cracks in which they have physical contact from all sides (thigmotaxis). Through this behavior, they often invade man-made crevices. This enables you to trigger smoke and fire alarms (for information on penetrating monitors, see Miscellaneous).

Many species of fringed winged winged birds can train numerous generations per year, especially in tropical latitudes or in permanently warm greenhouses. However, many species of the temperate zones develop only one generation per year. The rhythm of development is often correlated with the flowering rhythm of the host plant.

mimicry

Various types of fringed winged birds use mimicry to camouflage themselves from enemies . The so-called Batessian mimicry, in which inedible or defensive animals are imitated in their appearance, is particularly important. Examples of this are the representatives of the genera Aeolothrips and Desmothrips , which try to deter with stripes on the wings. In general, camouflages as small wasps or bed bugs are common. A number of species from both subordinates imitate ants in physique and behavior .

Symbiosis and parasitism

Symbiotic intestinal bacteria of the genus Erwinia have been detected in plant-sucking fringed- winged species. The influence of the bacteria on the species Frankliniella occidentalis , which has been particularly well investigated as a plant pest, shows that the fringed-winged birds can benefit or suffer disadvantages from the bacteria, depending on external conditions. Obligatory endosymbionts, as they have been demonstrated by other plant-sucking insect groups, do not seem to exist in fringed-winged birds.

As specialized parasitoids of fringed-winged wingers, ore wasps of the family Eulophidae have become known, which parasitize in the larvae. The ore wasp , which parasitizes in Frankliniella occidentalis, Ceranisus menes , was examined for its suitability for biological pest control without it having been used so far.

So far only two species of fringed winged fly have been discovered that parasitize on other animals. The South American species Aulacothrips dictyotus lives under the wings or the larval wing sheaths of the cicada species Aethalion reticulatum . Aulacothrips rarely or never leaves its host, both the pupae resting and the oviposition take place on the host. A second parasitic species in the genus was recently discovered.

Sociality

Some Australian thrips that live in self-made, blister-like leaf galls of acacias have developed approaches to sociality . Some individuals develop into "soldiers" here, who are characterized by their height, but only have limited reproductive capabilities. Its task is to defend the bile against other species of fringed winged winged birds that use the bile without being able to produce it (kleptoparasites).

One species of kleptoparasite ( Phallothrips houstoni ) has developed a remarkable life cycle. It invades galls that produce other species of thrips (of the genus Iotatubothrips ) on casuarinas . The female locks herself in a compartment that is separated by a self-made partition. Their first generation of offspring consists of a morph of particularly large, heavily sclerotized and wingless animals. These leave the compartment, then kill all animals of the gall producer and thus take over the gall for related offspring of their own species.

Economic factors

Fringed winged pests

Some fringed winged plants cause leaf damage to plants, so they are classified as pests and controlled by humans. Scirtothrips dorsalis and Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis are particularly feared pests in subtropical and tropical countries. In many cases, the main damage lies in the visual impairment of fruits or leaves (of ornamental plants), which can greatly reduce the commercial value. Most of the species known as pests are polyphagous generalists. 26 native species are listed as pests by the plant protection authorities in Germany . Most significant of these is the immigrant (neozoon) Frankliniella occidentalis ; also of importance are Frankliniella intonsa , Thrips tabaci ( "Zwiebelthrips") and Parthenothrips dracaenae . In Central Europe , only three species are of concern as pests in cereals: Limothrips cerealium , Limothrips denticornis and Haplothrips aculeatus . Most of the damage is considered minor. The plant protection authorities only recommend the use of insecticides in the event of severe infestation (damage threshold principle). Fringe-winged birds are hardly harmful because of the direct damage to plants (which are often hardly detectable), but as vectors (carriers) of viral diseases. A number of species of the genus Tospovirus ( Bunyaviridae ) are spread exclusively by fringed winged birds (14 species known as vectors).

A number of fringed winged species are used for biological pest control , i. H. as beneficial insects. The most widespread is the use of species of the genus Franklinothrips , especially Franklinothrips vespiformis . It is used exclusively in greenhouses, mostly against other species of thrips. Similar to plant pests carried over with crops, the species can easily escape into the wild due to its way of life and is one of the 52 species (neozoa) introduced into Europe. Since the main problem of use is the sensitivity of this tropical species to cold in all life stages, an actual settlement in the field is unlikely.

Fringed wings as pests

A number of fringed-winged species have been found to sting people occasionally, mostly outdoors in hot muggy weather and in large numbers. They pierce the skin with their stabbing mouthparts and release some saliva, most often on the bare arms. The result of the bite is skin lesions and a red, inflammatory swelling, very similar to a mosquito bite. Stings are known both from predatory species and from pure herbivores, feeding through blood is in no case possible. It is assumed that the animals are either misdirected by exhalations from the skin or that they are trying to absorb moisture.

Fringed wings and TFT monitors

For owners of TFT monitors , fringed wings can be a nuisance: If the animal crawls through the ventilation slots into the flat screen, it can get between the panel glass and the diffuser film and be trapped there. A living, moving insect is no less disruptive than a deceased one that remains in place on the monitor image. At the request of the computer magazine c't , Samsung confirmed that “no dust, animals or foreign bodies should get between the diffuser film and the TFT panel”. Other manufacturers do not rule out a warranty claim , as it is a matter of "impermissible dirt particles", however, according to research by Prad.de , processing via the various service providers is differently simple.

Combat

Fringed wings can be controlled using various methods. In addition to preventive methods, such as isolating the plant for a few days before applying it to the culture, showering infested plants with soapy water is a relatively simple method that can also be used at home. In the case of flying species, sticky boards in colors such as light blue and yellow matched to fringed wings can also help . In the agricultural sector, where these home remedies are unsuitable for use, attempts are sometimes made to master the situation through biological pest control . Here z. B. the introduction of predatory mites of the genus Amblyseius , predatory flower bugs of the genus Orius or larvae of the lacewing Chrysoperla carnea . When nematodes such as Steinernema , Heterorhabditis and Thripinema are spread , attempts are made to damage the pupae living in the soil. Another approach is the use of entomopathogenic mushrooms . The main problem here, however, is that the required humidity and the temperatures that are tailored to the fungus are often difficult to achieve. Of course, pesticides and insecticides are also sprayed. However, the sometimes enormous number of fringed-winged birds in a field, which can reproduce without a partner, can easily develop resistant representatives. None of the currently approved insecticides has e.g. B. against Frankliniella occidentalis still satisfactory effect.

Systematics

Tribal history

The oldest currently known paleontological finds date to the late Triassic , around 200 million years ago. The species Triassothrips virginicus from Virginia and Kazachothrips triassicus from Kazakhstan found from this age can be assigned to the Aeolothripidae , a family of the Thysanoptera. From the following Jurassic and Upper Cretaceous Period , some finds in Eurasia and North America can be reported. Various Cretaceous and Tertiary amber deposits provided a rich fauna of this insect order. Almost all of the species described from the Eocene Baltic amber belong to recent families, around a third of the species belong to recent genera.

External system

In the cladistics , the order Thysanoptera is compared to the order of the Schnabelkerfe (Hemiptera) within the Condylognatha . This in turn stands opposite the Psocodea within the Acercaria . The Acercaria probably form the dichotomous sister group of the ground lice (Zoraptera) within the Paraneoptera .

| Paraneoptera |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Internal system

The Thysanoptera are divided into the two suborders Tubulifera and Terebrantia , which in turn are divided into the nine families listed below. Of these, only the Thripidae and the Phlaeothripidae are divided into further subfamilies. The system at lower levels is very controversial and complex due to the fact that several monotypical genres have been described over the years . To date there have been no comprehensive genetic studies of the great abundance of species (approx. 5,500) that would bring new knowledge from a phylogenetic point of view. The Merothripidae are considered to be the most primitive family with the most plesiomorphic characteristics. The following shows the system down to the subfamily level. The species numbers are attached (Mound & Morris 2007 according to the world checklist (cf. web links)).

-

Terebrantia

- Adiheterothripidae (6 species)

- Aeolothripidae (190 species)

- Fauriellidae (5 species)

- Heterothripidae (70 species)

- Melanthripidae (65 species)

- Merothripidae (15 species)

-

Thripidae

- Dendrothripinae (95 species)

- Panchaetothripinae (125 species)

- Sericothripinae (140 species)

- Thripinae (1,700 species)

- Uzelothripidae (1 species)

-

Tubulifera

-

Phlaeothripidae

- Idolothripinae (2,800 species)

- Phlaeothripinae (700 species)

-

Phlaeothripidae

Types (selection)

History of exploration

The first known illustration of a fringed wing was the drawing made in 1691 by the Jesuit father Filippo Bonanni of a representative of the genus Haplothrips . The next mention is made by Carl de Geer in 1744. He coined the name Phyasapus (bladder foot) with his description, as the ends of the front pairs of legs reminded him too strongly of bags. The name thrips was ultimately coined by Carl von Linné when he summarized 11 species under this generic name in his Systema naturae in 1758 and 1790. Johann August Ephraim Goeze wrote in his Entomological Entries in 1778 ... in a footnote: "This sex [meaning the genus Thrips described by Linnaeus ] is not to be confused with certain small borer beetles in the wood, which the ancient people called thrips." Why Linnaeus this one Chose name, he unfortunately did not write.

The name Thysanoptera followed with the description of Alexander Henry Haliday in 1836, in which he also described 33 previously unknown species and raised the fringed winged to the rank of order. After some smaller work by various researchers, Uzel presented the monograph of the order Thysanoptera in 1895 , in which he described 135 species.

Trivia

Fringed wings in music

A song is dedicated to the fringed wing under the title Thunderstorm . It can be found on the CD ears post , the second album by singer / songwriter Jasper März .

swell

literature

- D. Grimaldi, A. Shmakov, N. Fraser: Mesozoic Thrips And Early Evolution Of The Order Thysanoptera (Insecta) . In: Journal of Paleontology . Vol. 78, No. 5, 9/2004, pp. 941-952.

- M. Hutchins et al. a. (Ed.): Thysanoptera. In: Insects. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Part 3. 2nd edition. Gale Group, 2003, ISBN 0-7876-5779-4 .

- T. Lewis: Thrips, Their Biology, Ecology and Economic Importance. Academic Press, New York 1973.

- W. A Mound, G. Kibbly: Thysanoptera: An Identification Guide. CAB International, 1998, ISBN 0-85199-211-0 .

- LA Mound, BS Heming: Thysanoptera. In: The Insects of Australia: a Textbook for Students and Research Workers . Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria 1991, pp. 510-515.

- LA Mound, (2005): Thysanoptera: diversity and interactions. In: Annual review of entomology. 50 (2005), pp. 247-269. doi: 10.1146 / annurev.ento.49.061802.123318

- Gert Schliephake : Thysanoptera, Fransenflügler. In: Stresemann - Excursion fauna of Germany . Volume 2. Spectrum Akademischer Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, pp. 155–159.

- Gerald Moritz: Thrips. Die Neue Brehm-Bücherei Vol. 663. Westarp Sciences, Hohenwarsleben 2006, ISBN 3-89432-891-6 .

- Hermann Priesner: Handbook of Zoology. Volume 4: Arthropoda. 2nd half: Insecta, Thysanoptera (Physopoda, cystopods). 1968, ISBN 3-11-000657-X .

- G. Schliephake, K.-H. Klimt: The animal world of Germany. Part 66: Thysanoptera, fringed winged wing. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena 1979.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernhard Klausnitzer: The insect fauna of Germany ("Entomofauna Germanica") - an overview. In: Linz biological contributions. 37th volume, issue 1, Linz 2005, pp. 87-97 ( PDF (779 kB) on ZOBODAT ).

- ↑ BS Heming (1971): Functional morphology of the thysanopteran pretarsus. Canadian Journal of Zoology 49 (1): 91-108. doi: 10.1139 / z71-014

- ↑ László Gozmány (Hrsgb.): Vocabularium nominum animalium Euroae septem linguis redactum. Akedémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1979. Volume 1, page 1045.

- ↑ a b Heinrich Kemper: The animal pests in language use. Duncker & Humblot, 1959. Limited preview on Google Books

- ↑ Diane E. Ullman, Daphne M. Westcot, Wayne B. Hunter, Ronald FLMau (1989): Internal anatomy and morphology of Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) with special reference to interactions between thrips and tomato spotted wilt virus. International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology 18 (5/6): 289-310. doi: 10.1016 / 0020-7322 (89) 90011-1

- ^ S. Sunada, H. Takashima, T. Hattori, K. Yasuda, K. Kawachi (2002): Fluid-dynamic characteristics of a bristled wing. Journal of Experimental Biology 205: 2737-2744.

- ↑ Bernard J. Crespi : Sex allocation ratio selection in Thysanoptera. In: Dana L. Wrensch, Mercedes A. Ebbert (Ed.): Evolution and diversity of sex ratio in insects and mites. Springer Verlag, 1992, ISBN 0-412-02211-7 .

- ↑ Trevor Lewis: Thrips. Their biology, ecology and economic importance. Academic Press, London, GB 1973, ISBN 0-12-447160-9 .

- ↑ Lewis J. Stannard, Jr .: A Synopsis of Some Ant-Mimicking Thrips, with Special Reference to the American Fauna (Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae: Idolothripinae). In: Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. Vol. 49, No.4 (1976), pp. 492-508.

- ↑ EJ de Vries, G. Jacobs, MW Sabelis, SBJ Menken, JAJ Breeuwer: Diet-dependent effects of gut bacteria on their insect host: the symbiosis of Erwinia sp. and western flower thrips. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 271 (1553) 2004, pp. 2171-2178, doi: 10.1098 / rspb.2004.2817

- ↑ Serguei V. Triapitsyn: Revision of Ceranisus and the related thrips-attacking entedonine genera (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) of the world. In: African Invertebrates. 46 (2005), pp. 261-315.

- ↑ Antoon JM Loomans: Exploration for hymenopterous parasitoids of thrips. In: Bulletin of Insectology. 59 (2) (2006), pp. 69-83.

- ↑ Thiago J. Izzo, Silvia MJ Pinent, Laurence A. Mound: Aulacothrips dictyotus (Heterothripidae), the first ectoparasitic thrips (Thysanoptera). In: Florida Entomologist. 85 (1) 2002, pp. 281-283. doi : 10.1653 / 0015-4040 (2002) 085 [0281: ADHTFE] 2.0.CO; 2

- ↑ Adriano Cavalleri, Lucas A. Kaminski, Milton de S. Mendonça Jr .: Ectoparasitism in Aulacothrips (Thysanoptera: Heterothripidae) revisited: Host diversity on honeydew-producing Hemiptera and description of a new species. In: Zoologischer Anzeiger. 249 (3-4) 2010, pp. 209-221. doi: 10.1016 / j.jcz.2010.09.002

- ↑ Thomas W. Chapman, Brenda D. Kranz, Kristi-Lee Bejah, David C. Morris, Michael P. Schwarz, Bernard J. Crespi: The evolution of soldier reproduction in social thrips. In: Behavioral Ecology. 13 (4) 2002, pp. 519-525. doi: 10.1093 / beheco / 13.4.519

- ↑ LA Mound, BJ Crespi, A. Tucker: Polymorphism and kleptoparasitism in thrips (Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae) from woody galls on Casuarina trees. In: Australian Journal of Entomology. 37 (1998), pp. 8-16. doi: 10.1111 / j.1440-6055.1998.tb01535.x

- ↑ David G. Riley, Shimat V. Joseph, Rajagopalbabu Srinivasan, Stanley Diffie: Thrips Vectors of Tospoviruses. In: Journal of Integrated Pest Management. 1 (2): 2011 doi: 10.1603 / IPM10020 open access ( Memento of the original from November 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 722 kB)

- ↑ Laurence a: Mound & Philippe Reynoud: Franklinothrips; a pantropical Thysanoptera genus of ant-mimicking obligate predators (Aeolothripidae). In: Zootaxa. 864 (2005), pp. 1-16.

- ^ P. Reynaud: Thrips (Thysanoptera). Chapter 13.1. In: A. Roques et al. a. (Ed.): Alien terrestrial arthropods of Europe. BioRisk 4 (2) 2010, pp. 767-791. doi: 10.3897 / biorisk.4.59

- ↑ G. Leigheb, R. Tiberio, G. Filosa, L. Bugatti, G. Ciattaglia: Thysanoptera dermatitis. In: Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 19 2005, pp. 722-724. doi: 10.1111 / j.1468-3083.2005.01243.x

- ↑ Carl C. Childers, Ramona J. Beshear, Galen Frantz, Marlon Nelms: A review of Thrips species biting man including records in Florida and Georgia between 1986-1997. In: Florida Entomologist. Vol. 88, No. 4 2005 download

- ↑ Dead insect in the picture: a warranty claim? Prad.de, accessed on May 23, 2015 .

- ↑ Thorsten Zegula, Peter Blaeser, Cetin Sengonca: Development of biological control methods against the harmful thrips Frankliniella occidentalis and Thrips palmi recently introduced to Central Europe and Germany in greenhouse cultivation. Agricultural Faculty of the University of Bonn, series of the teaching and research focus USL, 102.

- ↑ George O. Poinar Jr.: Life in Amber. Stanford 1992.

- ↑ see: Laurence A. Mound & David C. Morris: The insect Order Thysanoptera: Classification versus Systematics. In: Zootaxa. 1668 (2007), pp. 395-411. download (PDF; 198 kB)