Monument protection and preservation in Thailand

Monument protection and monument preservation in Thailand deal with the legal basis, the administrative organization and the concrete measures of monument protection , as well as with the methods of monument preservation in the Kingdom of Thailand resp. the former Siam (until 1939). The heritage protection and monument preservation tradition in Thailand goes back to the middle of the 19th century. In today's times of increasing threat to cultural goods , they are becoming increasingly important for national awareness as well as for the interests of cultural tourism.

Framework

The oldest archaeological relics of the Thai cultural area come from the Neolithic of the 6th millennium BC. A first civilization in the narrower sense emerged with the Dvaravati culture in the sixth century of our era. The first, smaller area state was Haripunjaya in the north of the country in the 8th / 9th. Founded Century. In the 13th century, the two larger territorial states of Sukhothai (in northern central Thailand in the first half of the 13th century) and Lan Na (in northern Thailand in the second half of the 13th century) emerged. From this time onwards one can speak of a state continuity of the country. In the following seven centuries an original Thai culture was able to develop. Their continuity was facilitated by the fact that the area we call Thailand today was never, not permanently and never completely occupied in its entirety, even if it was due to the location of the country between the two Burmese states in the west and the Khmer in the east, repeatedly exposed to massive wars of aggression and has been temporarily occupied in parts. Furthermore, Thailand was the only country in Southeast Asia that was never colonized , which was not least due to the skillful foreign policy of the rulers of the Chakri dynasty and their governments, even if they made considerable territorial concessions to the colonial powers on all of the country's borders at the time ( French Indochina , Federated Malaysian States / Non- Federated Malaysian States and British India ). In this way an authentic culture could develop and maintain almost without prejudice to cultural imperialist endeavors. Only with the Vietnam War (1965-1975), in which the country served as a resting and recreational area for the US armed forces, then through the mass tourism that began in the mid-1970s and finally through the consequences of globalization , this authenticity has been and is now For half a century it has been beset and changed in ever increasing and faster ways.

- See also History of Thailand

history

The first law for the protection of cultural property in Thailand was enacted at the beginning of the rule of King Mongkut (also Phra Chom Klao or Rama IV, 1851–1868) in 1851 and was called the "Proclamation on Temple Boundaries and Temple Looters". This legislation was in the context of the king's diplomacy, which successfully performed a balancing act in an effort to open up the country to positive international impulses on the one hand and to establish relationships with the western powers of the time, while on the other hand destructive western influences or even to prevent direct colonization. In keeping with the king's personal interests in history , art history, and archeology, a small intellectual elite was formed who carried out a number of archaeological studies and organized museum exhibitions. Although these projects were a private affair of the king and not an official government program, they nonetheless helped to make the preservation of cultural heritage a generally recognized value and to raise awareness of monument protection issues among the more educated public. By initiating what we now call monument protection and preservation, the king awakened an awareness of the value of culture in his subjects and used this as a welcome means of developing national awareness and unity.

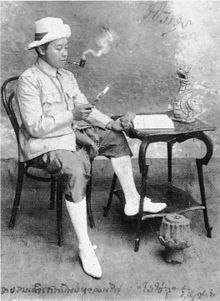

His son and successor, King Chulalongkorn (also Phra Chunlachom Klao or Rama V, the Great, 1868–1910) successfully continued his father's policy, intensifying and accelerating it. Chulalongkorn also shared his interest in the past. He wrote about archaeological topics himself, installed a museum in his palace in 1874, sought the return of stolen objects at the Ethnological Museum in Berlin in 1886 , founded the museum department as a state authority in 1888 and founded the antiques club in 1907, which is dedicated to the study of archeology , History and Art History promoted the Literature Club in 1914. The first scientific excavation in Ayutthaya also took place during his time . During a long trip in 1897 he had visited Thebes , Giza , Pompeii , Rome , Florence and Venice , among others . Impressed and influenced by the palaces and monuments he had got to know on his journey, he built a summer palace in the old capital Ayutthaya in order to create a continuity between its old, respected dynasties (1351–1767) and his own, the Chakri dynasty ( since 1782) to demonstrate.

The subsequent King Vajiravudh (also Phra Mongkut Klao or Rama VI., 1910-1925) was a student of history ( University of Oxford ) and an active archaeological pioneer (for example in the exploration of the Thanon Phra Ruang and the ancient sites of Sukhothai in 1907 ) in the tradition of its two predecessors. During his reign, monument protection in Thailand reached a modern level of bureaucratic form with a significant increase in the importance of the protection, care and restoration of cultural assets, including ancient monuments, ancient objects, art objects and archaeological sites. All of these matters have been overseen by the Fine Arts Department (FAD) established in 1911 since that time . With the help of its 13 regional offices spread all over the country, the FAD takes care of all aspects of monument protection and preservation. All regional offices have specialized sub-departments, including an academic research department, a monument preservation department and a technical department.

The protection and maintenance of the cultural heritage finally entered an even more scientific phase in an early period of the reign of King Bhumibol Adulyadej (also Bhumibol the Great or Rama IX., 1946-2016). A milestone was the enactment of the Act of Ancient Monuments, Antiques, Objects of Art and National Museums on August 2, 1961 and the ministerial decrees based on it. Among other things, since the entry into force of this law, the dating of archaeological finds has only been based on reliable methods, the restoration method of anastilosis has become common practice in Thailand and much more. By decentralizing the management of monuments and a higher degree of public participation and cooperation in the protection of cultural assets, the law adapted to changing social framework conditions. Further regulations followed that supported, strengthened, specified or developed this law, such as the 1985 FAD decree on the preservation of monuments. A number of articles of the Venice Charter have been adopted in accordance with the 1985 decree. This was greatly facilitated by Thailand's accession to the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), which was also completed in 1985 . All of these steps and enactments following the 1961 Act resulted in stricter procedures with clear guidelines, rules and regulations on monument preservation.

The extraordinary importance of cultural monuments for politics and society in Southeast Asian countries may be evident from a singularity of history, the border conflict between Cambodia and Thailand over Prasat Preah Vihear, which has meanwhile been declared a (Cambodian) world cultural heritage . This conflict, which smoldered for several decades and flared up again and again at different intensities - ultimately a late consequence of the colonial policy of the 19th and 20th centuries - escalated in 2008 to the point of military clashes between the two states with several dead and injured.

Monument Protection Act of 1961

The basis of the Thai monument protection is the "Law on Ancient Monuments, Antiques, Works of Art and National Museums" of August 2, 1961 and the ministerial decrees based on it. With this law, Thailand got a monument right that endowed the FAD and the responsible authorities with very far-reaching powers compared to other countries. In a total of 40 articles, the law regulates all matters relating to the objects defined therein.

Preamble (Articles 1 to 6)

- Articles 1 to 3 regulate the name and the entry into force of the law as well as the fact that this law makes the two previous laws of 1934 and 1943 obsolete.

- Article 4 contains important definitions of terms. As "Ancient Monuments" (ancient monuments) are defined immovable property, (which are by their age, their architectural characteristics and its historical significance for historical science, art (history) or the archeology of use here is not between historical buildings and ground monuments differentiated , the legal texts relate equally to both). The law defines “ancient objects” as things that have arisen naturally, or were created by humans, or are part of an ancient monument, a human skeleton or animal remains and which, due to their age, are the characteristics of them Manufacture or their historical significance are useful in the fields of art, history or archeology. "Art objects" are understood to mean objects that have been produced by handicraft and are considered valuable in the field of art. “Minister” refers to the specialist minister executing this law (in the sense of the ministry), with "general director" is the general director (in the sense of the general directorate) of the Fine Arts Department (according to the German understanding, roughly the cultural department of the Departmental Ministry) and a "responsible official" is a person appointed by the executing minister (in the meaning of the competent authority).

- Articles 5 and 6 regulate the responsibilities and competences of the Ministry and the Directorate General. In particular, it is about the possibility of appointing further "responsible officials" and, in cooperation with the provincial governments, to set up, so to speak, lower monument protection authorities.

Ancient monuments [architectural and ground monuments] (Articles 7 to 13)

- Section 7 grants the General Management the power to declare any monument it deems suitable by publication in the official government gazette ( Royal Thai Government Gazette ) as a protected monument and to determine the size of the necessary area around the monument. This area should be protected like the monument itself. Changes to or deletions from the list of monuments must also be published in the government gazette. If the monument or property is owned or owned by another person, this person must be informed by the General Management. The owner then has 30 days to apply for a court ruling against the registration or the measurement of the property size. If he fails to do so or if the court rejects the action in the last instance, the General Management can proceed with the registration procedure.

- Article 8 stipulates that all monuments registered under the previously applicable legal provisions are to be treated as if they had been registered under this law.

- Article 9 stipulates that in the event that a registered ancient monument owned or legally owned by any person decays or becomes dilapidated or damaged, the owner or holder must notify the General Management within 30 days of becoming aware of the damage.

- Article 10 regulates that no one is allowed to restore or modify a registered monument, or carry out any excavations in the surrounding protected area, unless he is acting on the instructions of the General Management or has its permission. If the permit is linked to conditions, these must be strictly observed.

- Article 11 gives the General Directorate the power to commission the official or any other person to carry out repairs or whatever may be necessary for any ancient monument, even if it is owned or owned by another person To maintain the original condition or to restore the monument, provided that the owner or owner must be informed beforehand.

- Article 12 states that in the event of the sale of a registered monument, the seller must notify the Directorate-General of the name and address of the buyer and the date of sale within 30 days of the sale. A person who acquires ownership of an ancient monument by inheritance or by declaration of will must notify the General Management of this within 60 days of the acquisition. In the case of an acquisition by several owners, it is sufficient for one of the co-owners to comply with this reporting requirement.

- Article 13 authorizes the Ministry, if it deems this to be appropriate for the preservation of a registered monument, to issue an order to conduct visits and, in particular, to charge an entry fee for monuments that are not privately owned. Such a decree can be issued with the same content for all monuments or differently for individual monuments.

Antiques and works of art (Articles 14 to 24)

- Article 14 authorizes the Directorate-General to register any antique or art object in the possession of the FAD as protected by entry in the Government Gazette if such object is of particular art, history or archeological value.

- Article 15 regulates that no one may restore or modify a registered antique or a registered work of art unless he has received the appropriate permission from the General Management. If this permit contains conditions, these must be observed.

- Article 16 stipulates that in the event that a registered antique or a registered work of art deteriorates, requires restoration, is damaged or lost, the owner must inform the General Management within 30 days of becoming aware of this change.

- Article 17 specifies that the seller of a registered antique or a registered art object must notify the General Management in writing of the name and address of the buyer and the date of sale within 30 days of the sale. A person who acquires ownership of a registered antique or a registered work of art through inheritance or a declaration of intent must inform the General Management of this within 60 days of the acquisition. If several people acquire ownership of one and the same item, it is sufficient for one of the co-owners to comply with this disclosure requirement.

- Article 18 states that antiques or works of art owned by the state and under the care and maintenance of the FAD are generally inalienable, unless otherwise provided by law. However, if there is a disproportionately large amount of the same items, the Directorate General may, with ministerial approval, dispose of some of these items through sale or exchange for the benefit of the national museums, or give them to the excavators as a reward or in exchange for their services.

- Article 19 stipulates that no one may trade in antiques or works of art or exhibit them in a business-like manner against the charging of entrance fees to the public, unless they have received a license from the General Management. The application for the license and its issue must be submitted to the General Management in the prescribed form. In the event that the Directorate General refuses to issue the license, an appeal against this decision can be lodged with the Ministry within 30 days. The decision of the ministry is then final.

- Article 20 goes on to state that, according to Article 19, the licensee must affix the license in a clearly visible manner in his business or exhibition space. Furthermore, he must truthfully keep a list of the antiques or art objects in his possession. This inventory must be submitted to the General Management in the prescribed form and kept ready in the business or exhibition rooms.

- Article 21 authorizes the competent authority to enter all localities in which antiques or works of art are traded or exhibited. This can be done to inspect whether a licensee is complying with the provisions of this law, or whether there is an antique or an art object that the licensee has illegally appropriated. The competent authority is empowered to seize any antique or any work of art that can reasonably be assumed to have been obtained through unlawful means.

- Article 22 stipulates that no one is permitted to export or otherwise take out of the territory of the Kingdom of an antique or an art object, regardless of whether the object is registered as protected or not, except by the General Management a permit was granted for this. The application for approval and the approval itself must be submitted to the General Management in the prescribed form. This provision does not apply to pure transit shipments. The licensee has to pay a fee set by ministerial decree for the approval.

- Article 23 stipulates that any person who intends to remove an antique or an art object temporarily from the territory of the Kingdom must apply to the Directorate General for a license. If this request is rejected, the applicant is entitled to lodge a complaint with the ministry within 30 days. The decision of the ministry is then final. If the General Directorate considers the application to be justified or the Ministry decides in favor of the applicant and the applicant has agreed to the conditions and requirements by paying a security deposit, the General Directorate shall issue a time-limited approval.

- Article 24 provides that antiques or works of art that have been buried, concealed or abandoned in such circumstances that no one can claim to be the original owner or owner, will become state property. Even if the place of burial, hiding, or loss is someone's property or possession. The finder of such an antique or such an art object must hand it over to the competent authority, the local administration or a police authority. Such a finder is entitled to a reward equal to one third of the value of the item found.

National museums (Articles 25 to 27)

- Article 25 states that national museums for the preservation of antiques and art objects that are in public ownership should be established. Every point at which a national museum is to be established, as well as a change in the status of a national museum, must be published by the ministry in the Government Gazette. The national museums that already existed when this law came into force should remain national museums under this new law.

- Article 26 stipulates that antiques and works of art that are in the hands of the state under the custody and care of the FAD should generally not be kept anywhere else than in the national museums. But in cases where it is impossible or inexpedient to keep them in the national museums, they can also be kept elsewhere, subject to ministerial approval. These provisions do not apply to antiques and works of art that are temporarily exhibited in other locations with ministerial approval, as well as to objects that are located outside the national museums for restoration purposes by order of the FAD. If there are a large number of similar antiques or works of art, the General Directorate may allow ministries or administrative departments to keep some pieces with them for a limited period of time.

- Article 27 empowers the Ministry to issue visitor regulations for the national museums as it deems appropriate in order to ensure appropriate behavior during the visits. The ministry can also set entrance fees. Both regulations are to be implemented by ministerial decree.

Archaeological Fund (Articles 28 to 30)

- Article 28 declares that an archaeological fund should be set up for expenditure on measures for the benefit of monuments and museum activities.

- Article 29 explains that this fund should be made up of monies acquired by the provisions of this law, monetary benefits arising from the monuments, monetary and property donations, as well as from the central fund or the capital that the FAD at the time of entry into force this law is available.

- Article 30 stipulates that the fund's bookkeeping and payment transactions must be carried out in compliance with ministerially prescribed rules.

Catalog of punishments (Articles 31 to 39)

- Article 31 provides that whoever finds an antique or an art object that has been buried, concealed or abandoned under such circumstances that no one can claim to be the original owner or owner, and that he keeps this opposite city for himself or for another , punishable by up to two years in prison or a fine or both.

- Article 32 states that anyone who destroys, damages or renders an ancient monument unusable, or who causes the monument to depreciate, should be punished with imprisonment of up to one year or a fine or both. If the monument concerned is a registered, protected monument, the perpetrator should be punished with imprisonment between three months and five years and an additional fine.

- Article 33 states that whoever damages or destroys an antique or an art object, or causes its loss or depreciation or its uselessness, should be punished with imprisonment for up to two years or a fine or both.

- Article 34 stipulates that those who violate the provisions of Articles 9, 12, 16, 17 or 20, or the ministerial decrees referred to in Articles 13 and 27, will be imprisoned for up to one month or a fine or both should be punished.

- Article 35 stipulates that anyone who violates the provisions of Article 10 or the conditions of the Directorate-General's authorization mentioned therein shall be punished with imprisonment for up to one year or a fine or both.

- Article 36 stipulates that anyone who violates the provisions of Article 15 or the conditions of the Directorate-General's authorization mentioned therein shall be punished with imprisonment for up to one year or a fine or both.

- Article 37 stipulates that anyone who violates the provisions of the first sentence of Article 19 should be punished with imprisonment for up to six months or a fine or both.

- Article 38 provides that anyone who, in violation of Article 22, exports or otherwise removes an unregistered antique or art object from the territory of the Kingdom of Thailand shall be punished with imprisonment for up to one year or a fine or both .

- Article 39 provides that anyone who, in violation of Article 22, exports or otherwise brings out of the territory of the Kingdom of Thailand a registered antique or a registered work of art shall be punished with imprisonment of between three months and one year and an additional fine.

Finally, Article 40 contains the transitional provisions of the law.

Structures and implementation

Monument protection and preservation are a task of the state in Thailand and are administered by two large departments of the Ministry of Culture, the "Office of Cultural Promotions", and the Fine Arts Department (FAD). While the former department is responsible for intangible cultural assets, monument protection and preservation in our sense fall within the area of responsibility of the FAD with its two subdivisions, the "Office of Archeology" and the "Office of National Museums" (office for national museums ), as well as its 13 regional offices. This responsibility includes the supervision of the meanwhile 41 national museums as well as the Thai UNESCO World Heritage (see below).

The Office of Archeology, established in 1908 as a private "Antiquity Club" and only later converted into a state administration, has been the central authority for the preservation of monuments since 1926 and is divided into seven departments: for general affairs, for planning and evaluation, for research, for the restoration and preservation of ancient monuments, for the preservation and restoration of murals and immovable sculptures, for inspection and maintenance as well as for historical park projects. Under the Monument Protection Act of 1961, the Office has the power to approve or reject requests for archaeological investigations on public land.

As many of these archaeological sites, ancient cities and monuments are Thailand's attractions and key destinations for tourism, they are promoted by the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) and its offices in the provinces and cities. In the past few decades, the participation of public and local associations in Thai monument preservation has increased significantly. There are now over 1,400 museums spread across the country. Most of them are not dependent on the government, but are financed by private foundations, gifts and donations and run by volunteers. These include archaeological museums, ceramic museums, ethnographic museums, traditionally built houses and much more.

The Thai archaeologists can be roughly divided into two large groups. One group, whose work focuses on the inventory, preservation and restoration of archaeological sites, is associated with the FAD, the other, whose main focus is on scientific research, with academic institutes such as universities and colleges. The first - and for a long time the only - training center for archaeologists in Thailand was the archaeological faculty of Silpakorn University in Bangkok. Most of the Thai archaeologists have studied at this university. The focus of the courses given there is on Thai archeology and archaeological practice. The course can be completed with a bachelor's , master's or doctorate . “Cultural Resource Management” has also been offered since 2006 (as a sub-graduate course) and 2007 (as a master’s course). In recent decades, other universities and colleges have the country (including the Thammasat University , the Chulalongkorn University , the Srinakharinwirot University (all three in Bangkok), the University of Khon Kaen , the Chiang Mai University and Burapha University ) started developing archaeological programs and adding archaeological courses to their curriculum without offering appropriate degrees.

Problems

Even if Thailand was fortunate not to have been robbed of its cultural goods by colonial powers on a large scale, the robbery grave mishap and even more the illegal international antiques trade, as in all emerging countries, represent a major problem in the protection of monuments in Thailand. On the part of the Thai government and The monument protection organizations try to counteract this problem - apart from through criminal consequences - in particular through bilateral and multilateral agreements and cooperation. The country has been a founding member of SEAMEO (Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization) since 1965 and of the associated SEAMEO-SPAFA (Southeast Asian Regional Center for Archeology and Fine Arts) since 1985 . In many cases, the robbers' graves are recruited from middlemen, mostly international antique dealers from Bangkok. Easily accessible, sparsely populated and very extensive prehistoric sites in central and northeastern Thailand are the preferred targets of the predators.

Another big problem lies in the contradiction that often emerges between the interests of the responsible and implementing authorities and scientists on the one hand and those of the local population on the other, for example when it comes to the restoration of a monument, recently as a spiritual or holy place is visited. The restoration technique of anastilosis , which is often used in Thailand , the first step of which is the complete removal of the monument, naturally meets with complete incomprehension and massive opposition from the faithful, in whose eyes the sanctuary is being destroyed.

The last major problem here is the award of public contracts for the preservation and restoration of archaeological remains and historical buildings in the hands of private companies. These companies often only approach their tasks from the technical side without having in-depth archaeological knowledge or the necessary professional empathy. They also focus on reducing costs and saving time in order to maximize profits. Potential, valuable knowledge is lost and the result of your work is often archaeologically incorrect and - from an aesthetic point of view - unsightly.

UNESCO World Heritage Sites and UNESCO World Document Heritage

Thailand has been a member of ICCROM since 1967 and in 1991 the first world heritage sites were recognized by UNESCO. There are currently five in the country, including three cultural heritage sites and two natural heritage sites, as well as four document sites.

The following were named world cultural heritage:

- 1991 the Sukhothai Historical Park and the Si Satchanalai and Kamphaeng Phet Historical Parks , which are related to it in spatial, temporal and cultural context

- 1991 Ayutthaya Historical Park

- 1992 the archaeological sites of Ban Chiang

- Impressions of the Thai world cultural heritage

Received their status as world natural heritage:

- 1991 Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary

- 2005 the Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex

The list of candidates also includes:

- since 2004 the Khmer buildings in the Phimai Historical Park (from the 11th century), in the Amphoe Phimai in the province of Nakhon Ratchasima and the associated temples Phanom Rung (from the 7th century) and Prasat Mueang Tam (from the 9th century) , both located in Buri Ram Province .

- since 2004 the Phu Phrabat Historical Park (with prehistoric sites from the sixth millennium BC to Khmer facilities), in the province of Udon Thani

- since 2011 the national park Kaeng Krachan

- since 2012 Wat Phra Mahathat Woramahawihan in Nakhon Si Thammarat

- since 2015 the monuments, archaeological sites and the cultural landscape of Chiang Mai , the capital of the Lan Na empire

- since 2017 the Wat Phra That Phanom in the Amphoe That Phanom in the province of Nakhon Phanom (from the 8th / 10th century), the historical buildings connected with it and its landscape

- Impressions of the Thai World Heritage candidates

A status as World Soundtrack Awards were given:

- 2003 the so-called inscription No. 1 of King Ramkhamhaeng from Sukhothai, the earliest evidence of Thai writing, today in the National Museum in Bangkok

- 2009 the document archive of King Chulalongkorn (1868–1910) in Bangkok

- 2011 the Epigraphic Archives at Wat Pho in Bangkok

- 2013 the minutes of the Council of the Siam Society in Bangkok

literature

- Waeowichian Abhichartvoraphan & Kenji Watanabe: A Review of Historic Monument Conservation in Thailand. Problems of Modern Heritage . In: Proceedings of the School of Engineering . Series E 40, Tokai University, Tokyo 2015, pp. 7-14, ISSN 0388-0788

- Fine Arts Department (Ed.): A Compilation of Royal Proclamations of King Rama IV, BE 2394-2404 . Fine Arts Department, Bangkok 1968

- Fine Arts Department (Ed.): Theory and Practice in the Preservation and Restoration of Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites . Fine Arts Department, Office of Archeology, Bangkok 1990.

- Fine Arts Department (Ed.): Ancient Monuments, Ancient Objects, Art Objects and National Museum Act of 1961 . Fine Arts Department, Bangkok 2005.

- Fine Arts Department (Ed.): 105 years of the Fine Arts Department . Fine Arts Department, Bangkok 2016.

- Pthomrerk Ketudhat: Development of archeology in Thailand . In: Muang Boran Journal , 21 (1-4), 1995, pp. 15-55, ISSN 0125-426X

- Thanik Lertcharnrit : Cultural Heritage Management in Thailand . In Encyclopedia of Global Archeology Springer, New York 2013, 2014, pp. 7287-7293, ISBN 978-1-4419-0426-3

- Thanik Lertcharnrit: Archaeological Heritage Management in Thailand . In: American Anthropologist , Vol. 119, No. 1, March 2017, pp. 134-136, ISSN 0002-7294

- Sayan Praicharnjit: The Management of Ancient Monuments, Ancient Objects, Art Objects and National museums by Local Administration Organizations . King Prajadhipok's Institute, Nonthaburi 2005.

- Maurizio Peleggi: National heritage and global tourism in Thailand : In: Annals of Tourism Research , Volume 23, Issue 2, 1996, pp. 432-448, ISSN 0160-7383

- Craig J. Reynolds: Globalization and cultural Nationalism in modern Thailand . In: Joel S. Kahn: Southeast Asian Identities. Culture and the Politics of Representation in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand . Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore 1998, pp. 115-145, ISBN 978-186-0642-45-6

- Kannikar Suteerattanapirom: The Development of Concept and Practice of Ancient Monuments Conservation in Thailand . In: Damrong Journal. Journal of the Faculty of Archeology , 5 (2), 2006, pp. 133-150, ISSN 1686-4395

Web links

- Official website of the Fine Arts Department (thai), accessed May 10, 2017

- Official website of the Siam Society , accessed on May 10, 2017, and the Archives of the Journal of Siam Society from 1904 on the official website of the Siam Society, accessed on May 10, 2017

- Official website of the Siamese Heritage Trust (English and Thai), accessed May 7, 2017

- Official website of the Southeast Asian Regional Center for Archeology and Fine Arts , accessed May 11, 2017

- Thailand Charter on Cultural Heritage Management on the official website of ICOMOS Thailand, accessed on May 8, 2017

- World cultural heritage and natural heritage sites of Thailand on the official website of the UNESCO World Heritage (English), accessed on May 11, 2017, as well as Thailand's World Document Heritage on the official website of the UNESCO World Document Heritage (English), accessed on May 11, 2017

Individual evidence

- ^ Preston Jones: The US Military and the Growth of Prostituation in Southeastern Asia . John Brown University, Siloam Springs (AR) undated

- ↑ Nick Kontogeorgopoulos: Tourism in Thailand. Patterns, Trends, and Limitations . In: Pacific Tourism Review , Vol. 2, University of Puget Sound, Tacoma (WA) 1998, pp. 225-238.

- ↑ Michael E. Jones: Thailand and globalization. The state of the utilities of buddhism culture, and education and the social movement of socially and spiritually engaged alternative education. In Rodney K. Hopson, Carol Camp Yeakey, Francis Musa Boakari (Eds.): Power, Voice and the Public Good. Schooling and Education in Global Societies (Advances in Education in Diverse Communities. Research, Policy and Practice, Volume 6) , Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2008, pp. 419–453, ISBN 978-1-84855-184-8 .

- ↑ Craig J. Reynolds: Globalization and cultural Nationalism in modern Thailand . In: Joel S. Kahn: Southeast Asian Identities. Culture and the Politics of Representation in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand . Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore 1998, pp. 115-145.

- ↑ Patrick Jory: Thai Identity, Globalization and Advertising Culture , in: Asia Studies Review , Volume 23, Issue 4, 1999, pp. 461-467.

- ↑ Kevin Hewison: Localism in Thailand. A study of globalization and its discontents . CSGR Working Paper No. 39/99, University of Warwick, Coventry 1999.

- ^ Fine Arts Department (ed.): A Compilation of Royal Proclamations of King Rama IV, BE 2394-2404 . Fine Arts Department, Bangkok 1968.

- ↑ Thanik Lertcharnrit: Cultural Heritage Management in Thailand . Springer, New York 2013.

- ↑ a b c d Thanik Lertcharnrit: Archaeological Heritage Management in Thailand . In: American Anthropologist , Vol. 119, No. 1, March 2017, p. 134.

- ↑ Thanik Lertcharnrit: Cultural Heritage Management in Thailand . Springer, New York 2013, p. 2.

- ^ Fine Arts Department (Ed.): 105 years of the Fine Arts Department . Fine Arts Department, Bangkok 2016.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Act of ancient monuments, antiques, objects of art and national museums of August 2, 1961 on the UNESCO website (English), accessed on May 7, 2017.

- ↑ a b Act of ancient monuments, antiques, objects of art and national museums of August 2, 1961 with subsequent ministerial decrees on the UNESCO website, accessed on May 7, 2017.

- ^ Fine Arts Department (ed.): Ancient Monuments, Ancient Objects, Art Objects and National Museum Act of 1961 . Fine Arts Department, Bangkok 2005.

- ↑ Waeowichian Abhichartvoraphan & Kenji Watanabe: A Review of Historic Monument Conservation in Thailand. Problems of Modern Heritage . In: Proceedings of the School of Engineering . Series E 40, Tokai University, Tokyo 2015, pp. 7-14.

- ↑ Sonja Meyer: The border conflict between Thailand and Cambodia . In Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs , 28 1, Hamburg University Press, Hamburg 2009, pp. 47-68, ISSN 1868-1034 .

- ↑ Regarding the definitions, it should be noted that in Thailand, compared to Western standards, they are quite “spongy”. This can essentially be traced back to Chulalongkorn, for whom the term cultural heritage referred to anything that was somehow old. So it is not surprising that there is still no clear and sharp definition of this term in the legislative context in Thailand. The formulations ancient monuments , ancient objects and art objects are commonly used. (Based on Thanik Lertcharnrit: Cultural Heritage Management in Thailand . Springer, New York 2013, p. 2)

- ↑ a b The English language text uses the term useful .

- ↑ a b c “Person” can mean a natural or legal person.

- ↑ Thanik Lertcharnrit: Archaeological Heritage Management in Thailand . In: American Anthropologist , Vol. 119, No. 1, March 2017, p. 134f.

- ↑ Thanik Lertcharnrit: Cultural Heritage Management in Thailand . Springer, New York 2013, pp. 2f.

- ↑ a b Thanik Lertcharnrit: Cultural Heritage Management in Thailand . Springer, New York 2013, p. 3.

- ↑ Sayan Praicharnjit: The Management of Ancient Monuments, Ancient Objects, Art Objects and National museum by Local Administration Organizations . King Prajadhipok's Institute, Nonthaburi 2005.

- ↑ Thanik Lertcharnrit: Archaeological Heritage Management in Thailand . In: American Anthropologist , Vol. 119, No. 1, March 2017, p. 135.

- ↑ Thanik Lertcharnrit: Cultural Heritage Management in Thailand . Springer, New York 2013, p. 4.

- ↑ a b Thanik Lertcharnrit: Cultural Heritage Management in Thailand . Springer, New York 2013, p. 5.

- ↑ Phuthorn Phumathon: The treasure hunter at Ban Wang Sai, Lopburi. A problem of archaeological site in Thailand . In Matichon Newspaper , September 17, 1993, p. 28.

- ↑ Thanik Lertcharnrit and Santhawee Niyomsap: Public peceptions and opinions about archeology in Thailand. A case of rural villagers in Central Thailand. In Muang Boran Journal , 34 (3), 2008, pp. 95-108.

- ↑ MLVarodom Suksawasdi: The recent restoration of Phra Chedi Luang. Problems and solutions . In Muang Boran Journal , 19 (2), 1993, pp. 155-171.

- ↑ Thanik Lertcharnrit: Cultural Heritage Management in Thailand . Springer, New York 2013, p. 6.

- ↑ The Sukhothai, Si Satchanalai and Kamphaeng Pet historical parks on the official UNESCO World Heritage website, accessed on May 10, 2017.

- ↑ Ayutthaya Historical Park on the official website of the UNESCO World Heritage, accessed on May 10, 2017.

- ↑ Archaeological sites of Ban Chiang on the official website of the UNESCO World Heritage, accessed on May 10, 2017.

- ↑ Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai Forest Complex on the UNESCO website, accessed on May 8, 2017.

- ↑ The King Ram Khamhaeng Inscription on the official website of the UNESCO World Document Heritage, accessed on May 11, 2017.

- ↑ Archival Documents of King Chulalongkorn's Transformation of Siam (1868-1910) on the official website of the UNESCO World Document Heritage, accessed on May 11, 2017.

- ↑ Epigraphic Archives of Wat Pho on the official website of the UNESCO World Heritage Site (English), accessed on May 11, 2017.

- ↑ "The Minute Books of the Council of the Siam Society", 100 years of recording international cooperation in research and the dissemination of knowledge in the arts and sciences on the official website of the UNESCO World Heritage Site (English), accessed on May 11, 2017 .