The big mistake

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | The big mistake |

| Original title | Il conformista |

| Country of production | Italy , France , Germany |

| original language | Italian , French |

| Publishing year | 1970 |

| length | 111 minutes |

| Age rating | FSK 18 |

| Rod | |

| Director | Bernardo Bertolucci |

| script | Bernardo Bertolucci |

| production | Maurizio Lodi-Fe |

| music | Georges Delerue |

| camera | Vittorio Storaro |

| cut | Franco Arcalli |

| occupation | |

| |

The Italian director Bernardo Bertolucci achieved his first commercial success in 1970 with the film Der große Errtum (original title: Il conformista , also Der Konformist ) ; international critics recognized him as one of the great contemporary directors. The international co-production, set in Rome and Paris, is based on the novel Der Konformist by Alberto Moravia . Jean-Louis Trintignant plays a conformist who joins the secret police of fascist Italy out of an exaggerated need to adapt. The plot leaves something open; Bertolucci tells the political espionage in a volatile chronology as the subjective memory of the main character, in a lyrical tone and with action elements. He and his cameraman and friend Vittorio Storaro developed a distinct visual style with luxurious furnishings and borrowings from the entertainment cinema of the 1930s. The lighting goes beyond the mere creation of moods, the light becomes a narrative medium that communicates content - especially in the implementation of Plato's allegory of the cave , the main metaphor of the work.

action

Starting position

As a 13-year-old Marcello Clerici learned of the intrusiveness of the chauffeur Lino in 1917 and then shot him with his pistol. From then on, he felt guilty about the murder that had apparently been committed, and Marcello developed the need to be as normal as possible and socially adapted. This is reinforced by the aversion to his parents - the father in the asylum, the mother a disguised morphinist - and by his unacknowledged homosexuality. In fascist Italy he made a career as a civil servant and joined the secret police in 1938 through the mediation of his friend Italo. At the same time he would like to marry a woman; his choice falls on the petty-bourgeois, not particularly clever Giulia. He offers the secret police to spy on his former professor Luca Quadri, who is now a leader of anti-fascists, during his honeymoon in Paris.

Further course

On the way to Quadri, Marcello receives the order in Ventimiglia to murder him. With Giulia, he visits the professor in Paris who has set up luxuriously in exile with his French wife Anna. Anna quickly recognizes Marcello's hostile intentions and lets him understand. He lets her feel that he desires her. When Anna is later alone with Giulia, she manages to approach Giulia sexually; they are observed by Marcello, who leaves the place again. With Marcello's knowledge, the secret police Manganiello discreetly follows the two couples during the subsequent shopping spree and dance evening. The professor sets out on a journey to his remote villa in Savoy ; Anna is supposed to come later. Marcello uses the opportunity to arrange the murder of the professor in such a way that Anna is not also killed: He has a trap prepared for Quadri on the way to Savoy. However, Anna decides to take a ride at the last minute, out of disappointment that she could not win Giulia's affection. When Marcello finds out, he follows Anna with Manganiello in a car to save her. They reach the couple in a forest where Quadri is trapped by the secret police. He is stabbed. Marcello watches the murder from his car. When Anna knocks pleadingly on the window, he watches her motionless. She escapes into the forest, where the henchmen shoot her down.

Five years later, in 1943, he lives with Giulia and her child in Giulia's apartment, where they had to take in war refugees. On the day Mussolini's government was overthrown , he met Lino again on the street, whom he believed he had shot in 1917. But he hadn't killed him, only injured him. Marcello shouts to bystanders, confused and excited, that Lino was a fascist and murderer and that he had killed Professor Quadri. After the collapse of the political system and his great mistake in life, the final shot turns to a naked rascal boy.

Narrative structure and perspective

Differences to the novel

The starting material for the plot was the 1951 novel Il conformista by Alberto Moravia . The novel is inspired by the murder of Moravia's cousins Nello and Carlo Rosselli in 1937 . Carlo Rosselli had opposed in Italy, fought in the Spanish Civil War and published a resistance newspaper in Paris. It was assumed that the murderers, French fascists, acted on behalf of Italian government agencies. Moravia did not put the murder case at the center of his novel, but the question of how educated civil servants could be involved in a murder. The book is considered to be unimaginative and repetitive, the motivation of its characters as implausible and it was not well received at the time.

The novel tells a tragedy determined by fate. Bertolucci, however, has replaced fate with Marcello's unconscious as the driver of the events in the script, which he wrote alone . Therefore, Marcello and his wife die, which appears in the book as a divine act of justice and was criticized as a deus-ex-machina solution. In the novel, Marcello learns about Quadri's murder from the newspaper, in the film he is present at the murder. In addition, in Moravia's book, Marcello witnesses a sexual act of his parents; Bertolucci left this out, but later he realized that this " primal scene ", transferred in the love act between Anna and Giulia, recurs.

Fragmented plot

Perhaps the most important change that Bertolucci has made to the novel is to break up the temporally linear narrative structure. The script offered a chronological sequence of events, but even while shooting, Bertolucci was fascinated by the idea of the car trip interspersed with flashbacks , which is why he had a lot of film material shot of it. For him it is the present tense of the story. More than two thirds of the plot is told in flashbacks, within which time jumps and even flashbacks occur in the flashback. The event is not conveyed by an omniscient narrator, but from the subjective point of view of the character Marcello, in terms of content according to his understanding and formally according to his imagination. However, only the superficial narrative action is fragmented and erratic. In the portrayal of the film's central conflict, Marcello's tortuous search for conformity, Bertolucci narrates purposefully. The conformity sought by Marcello takes concrete form in the form of marriage and loyalty to the state. Anna in particular repeatedly endangers both, until his striving for normality culminates in murder, with which he believes he will ensure his loyalty to his wife and the state. But after the fall of this state, its non-conforming individuality comes to the fore.

The flashbacks depict events that may have shaped Marcello's psyche and curriculum vitae. Their apparently chaotic arrangement represents Marcello's work of memory; this is not tied to temporal logic and jumps and jumps across the time axis with ease. It is inconspicuous associations that trigger unexpected memories. The film thus makes use of structures similar to those in Proust's literary work . Marcello's memories form a stream of consciousness so that the narrative structure is more related to surrealist films than to conventional entertainment cinema. Of course, this stream is not uncontrolled, but rather testifies to conscious narrative decisions by Bertolucci. The memories are often imprecise or distorted; Expressionist camera work and equipment characterize her and thus Marcello as abnormal. Although most of the shots of the camera in the murder sequence do not show Marcello's subjective gaze, the impression can arise that the murder is depicted from his perspective. In addition to three detailed shots of his eyes, the previous subjective structure of the film contributes to this. "With this, Bertolucci shows that the perspective in films can not only be achieved using the camera if it suggests identification with the figure, but also through the narrative structure."

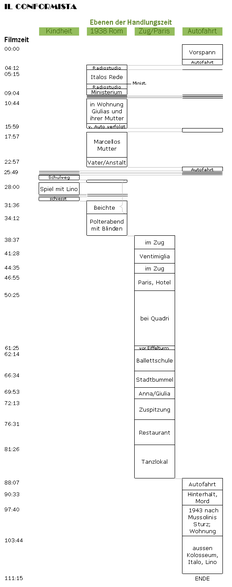

Several time levels can be identified in the above linearized plot. The first, most distant, time frame is the day in Marcello's childhood when he shoots Lino. On a second level in 1938 is his entry into the party and the subsequent visit to the minister. The engagement to Giulia and the confession form a further period; Whether this level is before, during or after the second is open. The visits to Marcello's mother and father cannot be clearly classified either. This is followed by the honeymoon. During a stopover in Ventimiglia, a small town on the border between Italy and France, it was noted that this sequence also took place on the border between dream and reality. The stay in Paris is a long, linearly narrated section. The subsequent car journey is the time frame from which most of the flashbacks occur. The film leads directly from the murder of Quadris and Anna (1938) to the day of Mussolini's fall (1943). The flashbacks to a different time level are usually introduced by brief flashbacks of a few seconds (and back again) before the narrative moves into the past for several minutes.

subjects

Since Bertolucci barely made a statement unambiguously, The Great Mistake triggered a multitude of interpretations that often contradict each other. The postmodern narrated film is an invitation to the audience for their own interpretation.

Political present and historiography

Bertolucci described himself as a communist from childhood and joined the Italian Communist Party two years before the Great Error emerged . He gave his answer to fascism during the opening credits, in the form of a red neon advertisement: It advertised La vie est à nous , which Jean Renoir shot on behalf of the French Communist Party for the 1936 election campaign . Renoir saw it as his contribution against National Socialism. Bertolucci: “I use history, but I don't make historical films; I only make seemingly historical films, because history cannot actually be portrayed using cinematic means: cinema only knows one narrative time, and that is the present. ”That is why the film deals with the present, which it historicizes. He investigated the dependence of the present on history and historiography the year before in the strategy of the spider . Here, too, he asks how to deal with Italy's fascist past, how it affects the present and how one can avoid ending up in the past again. He focuses more on the political meaning than the novel and supplements the plot with the agonizing, long murder. He accuses the Italian bourgeoisie of that time of "ethical-political indifference". Unfortunately, he says, the ideas of many Italians about normality and abnormality have remained the same since then.

conformism

Both Quadri and Italo doubt that Marcello is a staunch fascist. His partisanship is reversible; after the fall of Mussolini, he will opportunistically switch to the side of the new normal. Rather, its conformism is based on psychology.

Suppressed sexuality as a cause of fascism

Bertolucci's film was read against the background of Wilhelm Reich's theories that repressive societies suppress the sex drive and thereby pervert it; it discharges into brutality and sadism. Such fascist prototypes have learned the obedience in the patriarchal family, which they also show to the state. In a sexually repressive society, fascism finds particularly many supporters. This approach was not uncommon in Italian cinema around 1970; and The Wretched of Luchino Visconti and investigations against one above suspicion citizens of Elio Petri show deformed protagonist. These films come from Marxist directors who had put the lower social classes at the center in their early works and now examined the bourgeoisie psychologically. The big mistake is to describe the political by sexual terms. “For Bertolucci, neurosis is the intersection of sex and politics, the blind spot in the perception of reality.” Poetry, psychology and politics are interwoven and are intended to reveal the perverse structures of the state. Marcello's incident with Lino is nested in a confession he has to make before marriage. The priest is outraged by the incident and other sexual "sins". But after Marcello Clerici has revealed himself as a subversive hunter, who as such will still commit many sins, the priest immediately absolves him of all sins. The scene suggests that the church supports the authoritarian state in influencing the citizen psychologically.

Bertolucci found himself exposed to accusations that the great error established too simple a causality between homosexuality and fascism. In particular, the final scene, which remains firmly in the audience's memory, suggests this connection, as it appears like a dramaturgical revelation. Bertolucci protested against it and emphasized that Clerici's sexual inclination was only one of many facets of his personality. Some of the criticism sees it similarly and credits the director for avoiding simple attempts at explanation.

Oedipal tragedy

The oedipal struggle, conflicts with fathers and father figures, is a recurring theme in Bertolucci's films. In it he processes his own experiences; he struggled for independence in the face of the influence of his own father Attilio , a famous poet, his film patron Pasolini and Godard , whose artistic influence on him was overwhelming.

Marcello's biological father used to be a fascist torturer himself and met Hitler. He went crazy because of his fault and suffers from seeing too much. Nevertheless, he cannot help Marcello to understand, since he has fled into madness and murmurs incessantly slaughter and melancholy . The second father figure, Marcello's philosophy professor Quadri, is of no help to him either. Marcello reports of a dream that he was blind, Quadri surgically restored his eyesight and he ran away with Quadri's wife. This dream is a reversal of the Oedipus drama. But Quadri leaves the country. The difficult search for a strong father figure leads to Marcello's reference to the fascist state, in which he finds the supreme patriarch. He transfers his desire for mother and family to his homeland and nation. The representatives of this state are Italo and Manganiello; the latter is a father figure who does not tolerate nonsense and Marcello warns not to reveal the matter. Its name refers to manganello , the club that the fascist black shirts used.

Exaggerated behavior

Marcello wants to gain control over his life. "If you feel different , you have a choice: either to fight against the existing power or to seek protection," said Bertolucci. The very desire to be compliant is an admission that you are not. Marcello tries to create stability and fends off any subversion against the order guaranteed by fascism, especially deviating from the norm. He hunts "other people in order not to feel chased by abnormality himself." The marriage with Giulia is not motivated by love and sexual desire, but is intended to strengthen the normality sought. In order not to attract attention, he pursues an exaggerated sense of honor and duty. At crucial moments, however, he is unable to act - he returns the weapon that Manganiello had given him for the murder. How much his fate is directed by others is symbolized by the fact that Manganiello and Lino chauffeur him through the film.

Outward appearance

Marcello doesn't feel comfortable in the crowd and is awkward in social interaction. He is often spatially isolated from other characters, especially in the murder scene. He appears “elegantly reserved, yet vulnerable”, an unstable character with a protective shield from the soul, who makes abrupt movements and always keeps his legs close together, even when he's running. Trintignant, as his portrayal of the figure is circumscribed, breaks through Freudian clichés; With tightly controlled gestures and speech, he creates a portrait of a weak man who leans against the strong. Only a slightly distorted smile and a tight stalk betrayed the true character behind the engaging appearance. His facial expressions never feel too much and never too little. He emphasizes the ambivalent character of the hero and keeps the audience at a distance.

Images of women

How Marcello and Giulia met is left out. It also remains open to what extent the marriage and the honeymoon serve to cover up the espionage mission; Marriage and civil service are closely intertwined. Giulia comes from a middle-class family; Marcello describes them as “completely kitchen and bed” and “mediocre” and that's why he chose them. In contrast to Marcello and Anna, she has a rather simple mind, superstitious, free from deep brooding and accepts herself just as she is. Her only concern is the confession that she is no longer a virgin; when her husband calmly takes note of this, she reacts relieved and not puzzled. For Bertolucci, because she accepts the murder as necessary for Marcello's career, she is a "monster of everyday fascism."

Anna is the clearest character in the film. Marcello quickly sees through it. Although mostly referred to as lesbian - she tries to seduce Giulia - she also offers herself to Marcello. He seems to be burning for her - has he recognized a kindred soul in her? Is it an oedipal longing for his professor's wife? Should it confirm its normality? Other memories are still uncertain. Lolling on the desk of the minister in Rome is a woman who is played by Dominique Sanda as well as the prostitute in Ventimiglia. Speculations that Anna might be a double agent can be refuted by the fact that Marcello remembers these scenes after meeting Anna; her face with these women could be a projection of Marcello, who now sees Anna in all seductresses. The two scenes in which the chauffeur Lino tries to seduce the young Marcello and Anna Giulia have formal similarities. The seducers blur their gender assignment. Lino takes on feminine features as he opens his long hair; Anna has a masculine gesture and actively seduces Giulia. Both Marcello and Giulia don't quite understand what is happening to them. Marcello may be reenacting his childhood experience with the lesbian love act.

From a feminist point of view, it is criticized that while Anna and Giulia's tango lesbian women are quite fond of it, they could feel betrayed by the fact that this dance aims to seduce Marcello and the male audience. A second objection is that the otherwise innovative narrative on the gender issue remains conventional and always retains a traditional male point of view. In addition, the lesbian Anna, who challenged the patriarchy and Catholic Italy because of Giulia's seduction, was evicted from the story by an act of violence. However, it should not be forgotten that the events are told as Marcello's subjective memory and correspond to his image of women.

Metafilmic discussion

That Bertolucci not only deals with father-son conflicts in general, but also very personally, can be seen in the figure of Professor Quadri. As a young filmmaker, Bertolucci was deeply impressed by the work of Jean-Luc Godard , who from 1960 broke with the cinematic narrative conventions of the time. Godard aimed to prevent the usual immersion of the audience in a plot and to draw their attention to the cinematic narrative means that construct "reality". In order to be more independent of economic constraints, he contented himself with small budgets. The first influences on Bertolucci's style can be seen in his Before the Revolution (1964). Most visibly, Bertolucci fell under Godard's spell with Partner (1968), where he completely gave up his own style and imitated his role model. Not only was the criticism rejected, he himself soon declared his partner unsuccessful. With the star-studded, visually baroque and artificially illuminated large-scale production The Great Error , he moved far in the opposite direction.

He changed the names of the professor and his wife, Edmondo and Lina in the novel, to Luca and Anna, after Godard and his former wife and actress Anna Karina . However, a similarity to the Italian luce for light can also be seen in the first name Luca . To make it clear, he took the liberty of giving Quadri Godard's real address (rue St. Jacques 17) and telephone number (26 15 37) in Paris. In addition, he had considered Wiazemsky for the role of Anna Anne Wiazemsky , with whom Godard was close friends. From 1967 onwards he had also radicalized himself politically and called for the destruction of conventional film language and entertainment cinema, because this was a capitalist manipulation of the masses. Bertolucci: "Well, maybe I'm Marcello, I make fascist films and I want to kill Godard, who is a revolutionary, makes revolutionary films and was my teacher."

When the film came out, it was suspected that Bertolucci wanted to consciously separate after his liberation from Godard's influence. The film is a "declaration of independence". The depiction of the murder of Quadri underlines this: The coat of one of the murderers hides the view of Quadri like a curtain that falls and rises. That has already been interpreted as meaning that Bertolucci with Quadri symbolized in Godard conclude want, but also reminiscent of representations of the assassination of Julius Caesar and advances Quadri or Godard so close to a tyrant. Bertolucci used this Shakespeare play as a model for a murder in the Spider's Strategy . A visual presentation was perhaps Shoot the Piano Player of Truffaut where followers woman shoot at an alpine Serpentine. It would be an homage to the renewing but popular Truffaut and a rejection of Godardian political films. Quadri's saying goes in the same direction: “The time for reflection is over. The time to act has come. ”This is a reversal of the opening monologue in Godard's The Little Soldier . Quadri's actions, however, consist of fleeing Italy and settling in comfortably in exile. Just as Godard took refuge in the production of idealistic, neglected films instead of facing the challenge of the mass audience. Quadri's fate is mapped out in its political impotence; Bertolucci let him and Anna die in his script because, although they were on the right side, they were still too bourgeois and decadent for him.

Plato's allegory of the cave as a cinematographic metaphor

The big mistake contains a cinematic implementation of Plato's allegory of the cave , a central teaching example of epistemology . This is based on slaves who have been chained in an underground cave since they were born and can only see one wall at a time. A fire burns behind them. Between the fire and them, behind a small wall, sculptures are carried past, which cast shadows on the visible wall. The slaves' idea of reality is made up of these shadows alone. Plato asked to get out of the cave and to go to the sun, source of truth. However, the cave dwellers kill anyone who returns with the truth - they don't want to see it.

The allegory of the cave is the pivot between the content and form of the Great Error . The sequence in Quadri's office is considered by some to be the real key to understanding the film, because it deals with how human delusion hinders the search for truth. When Marcello visits Quadri's office, he locks the window on the side so that daylight only comes from one direction. He alludes to Plato as an attempt to deceive the professor about his true intentions, i.e. to blind him. Quadri warns that the Italian people see shadows of reality instead of reality; but we only see him as an outline in the backlight, which weakens his point of view. Marcello shows the height of the sculptures with a raised hand, but his shadow on the wall behind him seems to make the Saluto romano . When Quadri opens the side window again and more light enters the room, Marcello, only a shadow in the picture, dissolves into nothing. Marcello knows Plato's parable, and yet he cannot see its meaning for himself. The last scene, in which Marcello is only dimly lit by a flickering fire and looks through bars at a rascal boy, also has an unmistakable similarity to Plato's cave. It is controversial whether Marcello now comes to the knowledge of his true nature or whether he has reached the cave and the shadows again.

Lack of cognitive ability and political blindness appear allegorically in the physical blindness of some figures, especially Italo, who represents the state of the Italian nation. Marcello's dream of having an eye operation by Quadri can also be interpreted in this sense. The motif is also found at the opposite end of the political spectrum with the blind flower seller in Paris singing the Internationale .

Fascism glorified energetic movement up to and including war. Marcello remains immobile at the sight of fascist violence; the film can be interpreted as a warning against passive viewing in the face of seductive fascism in action. The reference can also apply to action and violence staged in entertainment films and their viewers. The slaves chained in Plato's cave resemble the audience immobilized in the cinema seats. It can be difficult for them to distinguish between projection and reality. The car window through which Marcello looks at the murder is like a movie screen. Bertolucci also blames his audience for “active-passive complicity with repressive, deadly violence”, who experience the scene with a corresponding discomfort.

The allegory of the cave can be regarded as the ancestor of any theoretical discussion about cinema, because it is the first time that images are generated. It is noticeable that Plato carefully designed the “projection conditions” in his parable: A small wall ensures that the shadows of the sculpture carriers and the slaves' own shadows are not thrown onto the wall. If these shadows were visible to the slaves, they would undermine the reality of what was listed and aroused suspicion in them. Bertolucci occasionally aims at precisely this reflection. He points out to the audience that reality is an asserted one and, with the complex time structure and some staged details, suggests a distanced view. They disrupt the audience's identification with the characters and undermine the usual way of seeing by exposing the illusion-generating mechanisms instead of veiling them as usual and faking what is shown as real. There is the transition from a painting of the bay to the “real” bay in Ventimiglia; the painting is inspired by René Magritte . It is also strikingly unreal that Quadri only has a few stains of blood after several knife wounds, but Anna, who shoots a hunter in the back once, has an obvious red color all over her face. The unreal is practically “performed” during the train journey, where the landscape and the Ligurian Sea can easily be seen as a rear projection through the window . Without a cut or recognizable reason, the light temperature outside changes within seconds between sunset red and cold gray blue.

Visual implementation

Light as a narrative

An important feature of the Nouvelle Vague , which began at the end of the 1950s, was the use of only natural light and instead of studio light, as was common in conventional entertainment cinema. Therefore, according to Bertolucci, artificial light sources were frowned upon as cheap kitsch among the younger directors of the 1960s. The big mistake for him was the first production he worked with it, and he discovered that artificial light can enormously enrich the language of a film. Bertolucci and Storaro use light as a narrative element that not only creates moods, but also transmits expressions, to a degree that is only found in few other films. Storaro understands the use of cameras and lighting not as painting, but as writing, because he uses light, movement and color to impress further statements on the pictures. This is most evident in the parable of the cave in Quadri's office above. On the other hand, the light is often in motion, for example the swinging lamp in the restaurant kitchen that Marcello uncovered when he was hiding from Manganiello in the dark, or the searchlights at the end of the film.

Storaro explained that Marcello lives in the shadows and wants to hide in the darkest corner. He strived for an immediacy between Marcello and his surroundings and created a “visual cage” around him. The light should not be able to penetrate the shadows, sharp contrasts should arouse fear of space . In the case of indoor shots, there is usually no outside world, no reality perceptible through the windows, because the dictatorship consisted only of appearances and scenery. To underline this, the scene in the insane asylum takes place outside . You used slats and tracing paper; In order to be able to use the full day for shooting, layers of gelatin were hung in front of the windows for the evening sequence in the dance hall during the light of day in order to weaken the outside light. In this hermetic world, Storaro wanted to avoid colors because they represent passions. At that time the public associated color with comedies and black and white with drama, but the solution of shooting in black and white was too easy for them; so he chose a monotonous color palette. On the trip to Paris, to a free country, he opens the cage and the shadows a little, the light becomes softer, the color warmer. Every time the plot leads back to Marcello's secret mission, Storaro puts him back in the visual cage. He calls the lighting in the officer's office in Ventimiglia one of the worst blunders of his career. Instead of creating a tension between light and dark, he designed it to be similar, i.e. bright and in mild contrast, to the rest of the Ventimiglia sequence.

One of the most discussed lighting effects is the scene in Giulia's apartment, where the venetian blinds screen the incoming light and Giulia is also wearing a zebra-striped dress. One of the interpretations offered is that the bright petty-bourgeois life is mixed with dark abnormality; another that Marcello remembers stripes and sees them "everywhere", similar to how he sees Anna's face in several women. The scene is said to be an exaggeration of the film noir style or "undoubtedly a reference to the prison of marriage that Marcello goes into." Storaro himself explained that he had too little an arc lamp, the outfitter only at the last minute with this Dress showed up and the combination was pure coincidence.

Camera work, image composition and equipment

The movements of the camera were not determined by Storaro, but by the director. One of the stylistic devices in the big mistake is that Marcello often moves away from other characters, but also the camera sometimes moves away from him. The camera movements are smooth, except for the scene in which the murderers are chasing Anna. Here Storaro and his assistant each operated a camera by hand. Extremely strained by the heaviness of the device, and also under time pressure because of an approaching storm, they captured tremendously shaking images that clearly stand out from the rest of the film. In the scene in which Marcello feels chased by a car, the image axis is oblique. It stays that way until the driver of the car, Manganiello, gets out and introduces himself to Marcello as a comrade. The change back to the straight image axis does not take place as usual with a cut, it is rather visible within one shot. This is one of the stylistic excesses that characterize Marcello's character. They expose the madness of his personality and the ideology that surrounds him. Marcello can often be seen through panes or as a reflection, an expression of his unstable self-image and the merging with his identification figures. One example is the reflection of Italo, which lies over Marcello in the radio studio. The compositions are often divided by strong lines and contrasts to emphasize Marcello's isolation from other figures.

Bertolucci used to say during the production process that the strategy of the spider was influenced by what he had seen himself, whereas the great error was influenced by the cinema. The fascist era is modeled on American and French films from the 1930s, the outfits and costumes of which are taken up again. The locations appear artificial and stylized. The characters sometimes behave like film stars of the time, for example when Anna imitates Marlene Dietrich with a cigarette in her mouth and her thumb hooked on the women's pants . The fact that the representatives of the fascist state always wear hats - even in bed - goes beyond a mere stylistic feature. A hat partially covers the face and uniformed the wearer, who is released from personal responsibility and guilt by the totalitarian state.

The last section from 1943 differs markedly from the previous parts of the film. If these took place during the day or on the blue Parisian evening, it takes place at night. The same apartment looks shabby five years later; the living conditions have a neorealistic touch. This can be interpreted in such a way that the past recalled by Marcello was more beautiful, or understand it as the effect of the war on everyday life. One review sees a figurative poetic justice in the fact that Marcello and Giulia's life is reduced to proletarian proportions. But Bertolucci also avoids making clear statements visually. "It would be disproportionate to use intellectual effort to bring clarity to scenes whose strength is precisely the ambivalence."

cut

In the first years of his cinematic work, Bertolucci cultivated a negative attitude towards editing. To avoid it as much as possible, he preferred plan sequences , because they were alive to him while a cut cools the material; the editing room looked to him like a slaughterhouse or a morgue. His collaboration with Franco Arcalli began with the big mistake , which was forced on him by the producer. Arcalli was able to convince and inspire him after just a few days. Thanks to Arcalli's assembly work, he discovered the creative possibilities that the cut offers, so that you can still improvise after the recordings, above all discover and make visible connections that were previously hidden. Bertolucci: “When cutting short shots together, he worked with a sense of proportion and pulled off the film at arm's length, just as the salespeople measure scraps of fabric. (...) It was as if the cut, which had previously always run horizontally from one side of the cutting table to the other, was now given a vertical dimension, as it were in successive layers, each of which revealed a deeper truth. ”This corresponds to Plato's demand to leave the cave and see things in a new light; the images take on a new meaning.

Manufacturing

The Italian television company RAI began funding feature films in the late 1960s. One of the first projects was Bertolucci's Strategy of the Spider (1969). This was followed immediately by The Big Mistake , whose budget is said to have been $ 750,000. Bertolucci and Storaro had known each other since Bertolucci's Before the Revolution (1964), when Storaro was a camera assistant and found the director to be very talented and competent, but also arrogant. In the strategy of the spider , he was a cameraman; this production established their decades of collaboration and friendship. The shooting of The Spider's Strategy took place in the fall of 1969, but this film was only released to the public after the Big Error , in August 1970. Shortly after the end Bertolucci asked his friend if he on his next project Il conformista where the cameraman still a swivel wanted, do the job needed. Storaro said goodbye and left the room. But Bertolucci followed suit and finally accepted Storaro's suggestion that this cameraman be and that his operator should bring Enrico Umetelli with him. For the cast of Anna Bertolucci was still thinking of Brigitte Bardot while developing the script , also considered Anne Wiazemsky , but decided on Sanda when he had seen her in Une femme douce . The film was shot in the winter of 1969/1970. Storaro was not available for a single day for pre-production and suitable locations sometimes had to be found while working. The location of some scenes at the beginning was the Palazzo dei Congressi in Rome , built in the fascist era , the Colosseum , the Castel Sant'Angelo and in Paris the Gare d'Orsay and the Eiffel Tower . The scene with the party that Italo held before Marcello's marriage was missing in the original version and was only reinstated in the 1990s.

Acceptance by critics and the public

The work was premiered at the Berlin Film Festival on July 1, 1970, under the German title Der Konformist ; The movie was shown in the cinemas as The Big Mistake .

Contemporary reactions

When it was published, the political position of the work was dealt with more than in later reviews. In Italy, left-wing critics resented Bertolucci for accepting money from the American Paramount and mixing profane sex with sacred politics. They accused him of portraying fascism as an individual-psychological problem instead of seeing it, like them, as part of the class struggle . The audience felt the murder scene at that time as brutal and shocking. Bertolucci also saw himself exposed to the accusation of nostalgia and “fascinating fascism” because of his stylized representation of the 1930s and the action elements. Der Spiegel saw a subtle, differentiated figure drawing done, but also sacrificed Bertolucci's earlier political panache. The critic Pauline Kael also judged mixed . The damned are hysterical, the great error is lyrical. Bertolucci's poetic expression creates a splendid, emotional film, the director's most accessible to date. Nevertheless, it is not a great film, because the style suppresses the content - and he indulges in fascist decadence - but the director is very promising for the future. If she claimed that the narrative structure caused unnecessary effort for the viewer, Positif found it very traditional, a broad audience would be able to follow the plot effortlessly.

But Bertolucci also received wide praise, especially for the visual poetry of the work. The Corriere della Sera commented : “Nobody should claim that the young director, who was previously regarded as the standard-bearer of the Italian avant-garde, has surrendered to the front of the commercial cinema. Rather, like The Strategy of the Spider, the film goes in search of the lyrical magic of bourgeois decay and into the undergrowth of the subconscious, from the end to the beginning, so to speak. (...) He trusts the evocative power of the figures and landscapes, which are caught in a dark, depraved mood. “ Avanti! found the film “remarkable: through the elegance of its expression, the psychological introspection, the power to conjure up, the quality of its style.” The film magazine Positif predicted after the premiere in Berlin that the great error would sell well, like The Damned . It is a spectacle in the established Italian tradition, which leaves nothing to be desired, and is luxuriously photographed. However, Marcello's psychoanalytic drawing is simplistic; and that family, social and sexual characteristics influence political attitudes no longer comes as a surprise. But the work proves that the future and salvation of Italian cinema does not lie in revolutionary bohemian cinema, but in commercial one. Bertolucci is a master, catches up with the great filmmakers of the peninsula: "The film impresses us more because of its tragic charm than because of its virulence, it is more of a tragic poem about error and delusion than a work of struggle." The magazine Sight & Sound said: “In this film, every sequence, every lyrical note is both spectacular and important. Visible action and psychological undercurrents meet in an electrifying way. "

Later assessments

In a Bertolucci monograph, Tonetti (1995) judges the great error : “Platonic philosophy is not only part of the content, it is also part of the cinematic narrative technique. The formal aspect (its incoherent moments and the daring flashbacks that arose during assembly) is a milestone, precisely because it does not aim at the pointless demonstration of narrative technique, but finds its substance in fresh ideas for classic, stimulating theories. "Kline (1987 ), who in his book on Bertolucci primarily applies a psychoanalytic perspective: “In the story of political intrigue and psychological complexity, Bertolucci subtly but definitely criticized the conformity that he and his audience have towards roles that are determined by the characteristics the cinema experience are given. "

Brief reviews in film lexicons highlight the visual style. The film-dienst says: “Coolly observing, stylistically refined and using a complicated flashback technique, Bertolucci's film analyzes the world of consciousness of the Italian bourgeoisie on a model case. Individual and political history are closely related to one another, although - despite his technical virtuosity - the combination of both aspects does not always seem compelling. "" The Chronicle of the Film "from Chronik-Verlag judges:" Bernardo Bertolucci uses the fluidly narrated film for the first time a wide audience. As in his earlier avant-garde films, he proves to be a master of effective visual design. ” The large film lexicon finds:“ The complicated flashbacks are sometimes confusing, which increases the appeal of this multi-layered work. The sophisticated optics, which are not limited to costumes and backdrops, but are particularly noticeable in Vittorio Storaro's carefully composed pictures, also played a large part in this. With Der Konformist Bertolucci achieved his greatest triumph to date with critics and audiences. ”It sounds similar in“ 1001 Films ”:“ In this film, Vittorio Storaro amazed with his camera technology. The color, camera position and equipment are used so well that the story is sometimes overlaid by the images. ”The scene in which Anna dances a tango with Giulia is particularly emphasized. That is "wonderfully erotic", one of the most romantic, sensual and splendid dance scenes ever filmed, "which has a provocative effect through its pure elegance."

Impact on Storaro and Bertolucci's careers

Vittorio Storaro's contribution to the Great Error had a lasting influence on the lighting in commercial film productions; it was a milestone in film history. As a pioneering act, the work influenced a whole generation of cameramen and is considered to be one of the greatest achievements of their craft. The producers, who had previously made sure that expensive stars were presented in the best light and that identifying figures remained recognizable, began more often to allow scenes to take place in the shadows. Francis Ford Coppola , admirer of the Great Error , portrayed characters in his godfather trilogy who, like Marcello, prefer to stay in the shadows. He took over the lighting concept, but tried in vain to win Storaro as cameraman for the second part .

In Bertolucci's career, the Great Error started an increase in available funds. His first four films took place in Italy, were cast with Italians and had a modest budget. The cast of the main role with the star Jean-Louis Trintignant and the submission of the popular Alberto Moravia made the film aimed at a wider audience. Commercial success and the proven ability to master complex interwoven narratives and to lead an international cast of actors opened the way for Bertolucci to more expensive productions such as The Last Tango in Paris and 1900 . Thematically, Bertolucci set on his previous film The Strategy of the Spider , which revolves around the past, father figures and betrayal. Stylistically, Der große Errum marked a turning point in his work. Before he had tried to renew the film language, now he used all visual and narrative means in free spaces within conventional cinema without ever completely abandoning the idea of authorship.

Awards

At the 1970 Berlin International Film Festival , Bertolucci won the Interfilm Prize and the film was nominated for the Golden Bear . He also received an Oscar nomination for the script.

literature

- Alberto Moravia : The conformist. Roman (original title: Il conformista ). German by Percy Eckstein and Wendla Lipsius . Wagenbach, Berlin 2009, 316 pp., ISBN 978-3-8031-2620-7

- Dietrich Kuhlbrodt : Bernardo Bertolucci . Film 24 series, Hanser Verlag, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-446-13164-7 (essayistic review)

- Bernd Kiefer: The big mistake / the conformist . In: Reclam classic films . Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-15-009418-6 , Volume 3, pp. 210-213 (general overview)

- Frédérique Devaux: Le mythe de la Caverne dans Le conformiste de Bernardo Bertolucci . In: CinémAction: Philosophy et cinéma . Corlet-Télérama 2000, ISBN 2-85480-932-7 , pp. 175-183 (French; deals in detail with the treatment of the allegory of the cave in The Great Error)

- Jean-Louis Baudry: Le dispositif: approches métapsychologiques de l'impression de réalité. Communications, Ecoles des hautes études en sciences sociales. Seuil, Paris 1975, pp. 56-72 (French; compares the facilities of the Platonic cave and the cinema with reference to a psychoanalytic view of the dream)

- Robert Ph. Kolker: Bernardo Bertolucci . British Film Institute, London 1985, ISBN 0-85170-166-3 , pp. 87-104 (English; focuses on stylistic aspects)

- Marcus Stiglegger : Il Conformista . In: Sadiconazista. Fascism and Sexuality in Film . Gardez! Verlag, St. Augustin 1999 (2nd edition 2000), ISBN 3-89796-009-5 , pp. 95-105 (thematically oriented film analysis)

Web links

- The great error in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Peterson, Thomas E.: Alberto Moravia. Twayne, New York 1996, ISBN 0-8057-8296-6 , pp. 65-66

- ^ A b Milano, Paolo: Moravia, Alberto: The conformist. Book review in: Commentary, New York, No. 13 1952, pp. 196-197

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Kline, T. Jefferson: Bertolucci's dream loom. University of Massachusetts Press, 1987, ISBN 0-87023-569-9 , pp. 82-104

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Devaux, Frédérique: Le mythe de la Caverne dans Le conformiste de Bernardo Bertolucci, in: CinémAction: Philosophie et cinéma. Corlet-Télérama, 2000, ISBN 2-85480-932-7 , pp. 175-183

- ↑ Bernardo Bertolucci in Gili, Jean: Le cinéma italien, Union Générales d'Editions, Paris 1978, ISBN 2-264-00955-1 , p. 44

- ↑ Bernardo Bertolucci in conversation with Sight & Sound, autumn 1972 edition. Marcello and Giulia are shot at by an Allied airplane in the novel.

- ↑ a b c Kidney, Peggy: Bertolucci's adaptation of The Conformist: A study of the function of the flashbacks in the narrative strategy of the film, in: Aycock, W. & Schoenecke M. (Eds.): Film and literature. A comparative approach to adaptation. Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock 1988. ISBN 0-89672-169-8 . P. 103

- ^ Tonetti, Claretta Micheletti: Bernardo Bertolucci. The cinema of ambiguity. Twayne Publishers, New York 1995, ISBN 0-8057-9313-5

- ↑ a b c Bernardo Bertolucci in: Ungari, Enzo: Bertolucci. Bahia Verlag, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-922699-21-9 , pp. 71-74. (Original: Ubulibri, Milan 1982)

- ↑ Kidney 1988, p. 97, similarly also Kiefer, Bernd: Der große Irrtum / Der Konformist, in: Reclam Filmklassiker, Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-15-009418-6 , Volume 3, p. 211

- ↑ a b c d Rush, Jeffrey S .: The Conformist (Il conformista), in: Magill's Survey of Cinema, Foreign Language Films, Volume 2, Salem Press, Englewood Cliffs NJ 1985, ISBN 0-89356-245-9 , p 615-619

- ^ Giora, Rachel / Ne'eman, Judd: Categorical organization in the narrative discourse: A semantic analysis of II conformista . Journal of Pragmatics, 26 1996, pp. 715-735

- ↑ Kidney 1988, pp. 98 and 101

- ↑ a b c Farber, Stephen: Film: Sex and Politics, Hudson Review, Summer 1971, 24: 2, pp. 306-308

- ↑ Loshitzky 1995, pp. 58-60; see. also Mellen 1971, p. 5.

- ↑ Positif July / August 1971: Les pannaux coulissants de Bertolucci, pp. 35–40

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Kolker, Robert Ph .: Bernardo Bertolucci. British Film Institute, London 1985, ISBN 0-85170-166-3 , pp. 87-104

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Mellen, Joan: Fascism in contemporary film. Film Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 4, Summer 1971, pp. 2-19

- ↑ Kidney 1988, pp. 102-103.

- ^ Kline, T. Jefferson: Il conformista. Iin: Bertellini, Giorgio (Ed.): The cinema of Italy. Wallflower Press, London 2004, ISBN 1-903364-99-X , p. 179.

- ↑ Tonetti 1995, p. 114

- ↑ Bernardo Bertolucci in Gili 1978, pp. 63-64.

- ^ Kuhlbrodt, Dietrich: Bernardo Bertolucci. Film 24 series, Hanser Verlag, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-446-13164-7 , p. 157; Kiefer 1995, p. 213; Bertin, Célia: Jean Renoir, cinéaste. Gallimard 1994, ISBN 2-07-031998-9 , p. 47

- ↑ Bernardo Bertolucci in Gili 1978, p. 72; see. also Filmkritik March 1971, pp. 143–144.

- Jump up ↑ Loshitzky, Yosefa: The radical faces of Godard and Bertolucci. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 1995, ISBN 0-8143-2446-0 , pp. 60-61.

- ↑ Kiefer 1995, pp. 212-213.

- ↑ a b c d e f Bernardo Bertolucci in conversation with Sight & Sound, autumn 1972 edition.

- ↑ Farber 1971, p. 306; Mellen 1971, p. 18; Giora / Ne'eman 1996, p. 731

- ↑ Witte, Karsten: The late mannerist. in: Bernardo Bertolucci. Film 24 series, Hanser Verlag, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-446-13164-7 , p. 53; Sight & Sound, Fall 1972; Mellen 1971, p. 6

- ↑ Picchietti, Virginia: Gender transgression in three Italian films. In: Forum Italicum, A Journal of Italian Studies, Vol. 38, No. 1, Spring 2004, p. 122.

- ↑ Kiefer 1995, p. 213.

- ↑ Kline 2004, p. 177

- ↑ Farber 1971, p. 305; also Weiss, Andrea: Vampires & Violets: Frauenliebe und Kino. German edition: Ed. Eberbach im eFeF-Verlag, Dortmund 1995, ISBN 3-905493-75-6 , p. 120. Original edition: Verlag Jonathan Cape, London 1992

- ↑ Mellen 1971, p. 3, Farber 1971, p. 306, Kolker 1985, p. 88.

- ↑ a b Kolker, Robert Ph .: Bernardo Bertolucci. British Film Institute, London 1985, ISBN 0-85170-166-3 , pp. 187-188

- ^ Kinder, Marsha: Bertolucci and the dance of danger, Sight and Sound, Herbst 1973, p. 187

- ↑ Kolker 1985, pp. 94-95 and 188

- ↑ Kline 2004, p. 175

- ↑ Bertolucci in conversation, in: Cineaste Magazine, Winter 1972–1973, New York.

- ↑ a b Kiefer 1995, p. 211

- ↑ Tonetti 1995, p. 114. In a similar sense, Farber 1971, p. 306.

- ↑ Kuhlbrodt 1982, p. 153, Tonetti 1995, p. 103, and Giora / Ne'eman 1996, p. 727.

- ^ Roud, Richard: Fathers and Sons, in: Sight and Sound, Spring 1971, p. 63; Kline 1987, p. 83.

- ↑ a b c Roud 1971, p. 64.

- ↑ Farber 1971, p. 306

- ↑ Tonetti 1995, p. 104 and p. 106

- ↑ Kiefer 1995, p. 212

- ↑ Kiefer 1995, p. 212, Tonetti 1995, p. 104, and Roud 1971, p. 63

- ↑ a b Monthly Film Bulletin, Volume 38, 1971, British Film Institute, pp. 237-238

- ↑ a b c Roud, Richard: Fathers and Sons, in: Sight and Sound, Spring 1971, p. 62.

- ↑ a b c d Kael, Pauline: The Conformist. The poetry of images. The New Yorker, March 27, 1971

- ^ Metzler Film Lexicon. Edited by Michael Töteberg. JB Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-476-02068-1 , pp. 140-141. Rush 1985, p. 619 also emphasizes the detachment.

- ↑ Tonetti 1995, pp. 109 and 116.

- ↑ a b c Film Critique March 1971, pp. 134–147

- ↑ Kuhlbrodt 1982, p. 147, Kiefer 1995, p. 213, Kolker 1985, p. 103, Kline 2004, p. 176, Rush 1985, p. 617.

- ↑ Giora / Ne'eman 1996, p. 728

- ↑ Picchietti 2004, pp. 123-126.

- ↑ Kline 2004, p. 174.

- ↑ a b Weiss 1995, pp. 119-120.

- ↑ Picchietti 2004, pp. 125-127; also Sheldon, Caroline, quoted. in: Witte, Karsten: The late mannerist, in: Bernardo Bertolucci. Film 24 series, Hanser Verlag, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-446-13164-7 , p. 50

- ↑ see the article on Partner (1968)

- ↑ Loshitzky 1995, p. 64

- ↑ Kline 2004, pp. 178-179

- ^ Monthly Film Bulletin, Vol. 38, 1971, British Film Institute, pp. 237-238; Tonetti 1995, pp. 105-107, and Kline 2004, p. 180

- ↑ Kolker 1985, p. 214

- ↑ Kline 2004, p. 178

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Vittorio Storaro in: Shadows of the Psyche, American Cinematographer February 2001, pp. 84–93

- ↑ Kuhlbrodt 1982, p. 156

- ↑ a b Tonetti 1995, pp. 116-121

- ↑ Vittorio Storaro speaks of a catharsis in: Shadows of the Psyche, American Cinematographer February 2001, p. 93.

- ↑ Witte, Karsten: The late mannerist, in: Bernardo Bertolucci. Film 24 series, Hanser Verlag, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-446-13164-7 , p. 52; Positif July / August 1971, p. 36; Kinder 1973, p. 187; Loshitzky 1995, p. 64.

- ↑ on the subject see Filmkritik March 1971, p. 137, Devaux 2000, p. 176, Loshitzky 1995, p. 62–63 and Kline 2004, p. 178 and 180.

- ↑ Baudry, Jean-Louis: Le dispositif: approches métapsychologiques de l'impression de réalité. Communications, Ecoles des hautes études en sciences sociales, Seuil, Paris 1975, p. 63

- ↑ Baudry 1975, p. 63

- ^ Vittorio Storaro in Film Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 3, spring 1982, p. 20

- ^ Vittorio Storaro in Guiding Light, American Cinematographer February 2001, p. 73, and in Film Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 3, spring 1982, p. 15

- ↑ Pizzello, p / Bailey, J .: Shadows of the psyche, American Cinematographer February 2001, page 85

- ^ Vittorio Storaro in: Shadows of the Psyche, American Cinematographer February 2001, pp. 87-88; Storaro in Film Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 3, Spring 1982, p. 20

- ^ Giora / Ne'eman 1996, p. 727

- ↑ Kuhlbrodt 1982, p. 146; Kiefer 1995, p. 213; also Metzler Film Lexikon. Edited by Michael Töteberg. JB Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-476-02068-1 , p. 140

- ^ Metzler Film Lexikon 2005, p. 140; see. also Vittorio Storaro in: Shadows of the Psyche, American Cinematographer February 2001, p. 89

- ↑ Positif No. 121, November 1970, p. 56; Sight & Sound, Fall 1972 edition; Loshitzky 1995, p. 62

- ↑ Tonetti 1995, p. 107; similarly also Mellen 1971, p. 5.

- ↑ Kuhlbrodt 1982, p. 146.

- ↑ Bertolucci in: Ungari 1984, p. 71; similarly in Gili 1978, p. 59

- ^ Film-Korrespondenz, March 1973, pp. 6–9

- ↑ Vittorio Storaro in Guiding Light, American Cinematographer February 2001, pp. 74 and 76

- ↑ regarding Sanda and Bardot: gem. Dominique Sanda in: Il voulait que je sois. Cahiers du cinéma No. 543, February 2000, supplement Hommage à R. Bresson, p. 12; Regarding Wiazemsky: Roud 1971, p. 64

- ↑ Sight and Sound, 1994, p. 54

- ↑ Kuhlbrodt 1982, pp. 238-239

- ↑ Der Spiegel No. 18/1971, p. 194

- ↑ Tonetti 1995, pp. 105-107.

- ↑ Loshitzky 1995, p. 67

- ↑ Der Spiegel: Marcello's End . In: Der Spiegel . No. 28 , 1970, pp. 130 ( online ).

- ↑ a b Positif No. 121 of November 1970, p. 56.

- ↑ Corriere della Sera, January 30, 1971, cited above. in: Dizionario del cinema italiano. Dal 1970 al 1979. Vol. 4, Volume 1, Gremese Editore, Rome 1996, p. 198

- ↑ Avanti, March 25, 1971, cit. in: Pitiot, Pierre and Mirabella, Jean-Claude: Sur Bertolucci. Editions Climats, Castelnau-le-Lez 1991, ISBN 2-907563-43-2 , pp. 103-104

- ↑ Tonetti 1995, p. 120

- ↑ The great error. In: Lexicon of International Films . Film service , accessed March 2, 2017 .

- ↑ The Chronicle of the Film. Chronik Verlag, Gütersloh / Munich 1994. ISBN 3-570-14337-6 , p. 390

- ↑ Dirk Manthey, Jörg Altendorf, Willy Loderhose (eds.): The large film lexicon. All top films from A-Z . Second edition, revised and expanded new edition. Volume III (H-L). Verlagsgruppe Milchstraße, Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-89324-126-4 , p. 1611 .

- ^ Schneider, Steven Jay (Ed.): 1001 Films. The best films of all time . Edition Olms, Zurich 2004.

- ↑ Kael 1971; Kline 1987, p. 95

- ↑ Foreword to Ed. P. 10, Fisher, Bob: Guiding Light, pp. 76-77, and Introduction to Shadows of the Psyche, p. 84, in: American Cinematographer February 2001

- ↑ Schumacher, Michael: Francis Ford Coppola. Bloomsbury, London 1999, ISBN 0-7475-4678-9 , p. 167

- ^ Wood, Mary P .: Italian cinema. Berg, Oxford and New York 2005, ISBN 1-84520-161-2 , p. 127

- ^ History of international film. Verlag JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2006, p. 542; and Russo, Paolo: Breve storia del cinema italiano. Lindau, Turin 2003, ISBN 88-7180-341-8 , p. 138