Seminole Wars

The Seminole Wars , sometimes called the Florida Wars , were three armed conflicts in Florida between various Indian tribes, which are collectively known as the Seminoles , and the United States . The First Seminole War lasted from 1817 to 1818, the Second Seminole War from 1835 to 1842, and the Third Seminole War from 1855 to 1858. The Second Seminole War, also often referred to as the Seminole War, was the longest war in the United States since the American Revolution fought until the Vietnam War.

background

Colonial Florida

The Indian population in Florida had steadily declined since the arrival of the first Europeans. The American indigenous population had little resistance to the diseases brought in from Europe. The crackdown on Indian revolts by the Spaniards also reduced the population, especially in northern Florida. Numerous raids by soldiers and their Indian allies from the British province of Carolina on the entire Florida peninsula had led to the fact that at the beginning of the 18th century almost the entire indigenous population was either killed or abducted. When Spain had to cede Florida to Great Britain in 1763, the Spaniards took the few surviving Indians with them to Cuba.

Groups of different Indian tribes from the southeastern United States then began to immigrate to Florida, which is no longer populated. After the Yamasee War (1715-1717), Yamasee Indians moved to Florida as an ally of the Spaniards after conflicts with the British. Likewise, more and more Creek Indians settled in Florida. A group of Indians from the Hitchiti tribe , the Miccosukee , settled in the area around what is now Lake Miccosukee near Tallahassee . This group has retained its independent identity as Miccosukee to this day. Another group from the Hitchiti tribe, headed by Cowkeeper , migrated to what is now Alachua County , an area where the Spanish raised cattle in the 17th century. The largest and most famous ranch was called Rancho de la Chua and the area was later named Alachua Prairie . The Spaniards in San Agustin , later St. Augustine, called these Indians Cimarrones , which means something like "savage" or "fugitive" and is the most likely origin of the term "Seminoles". This name was eventually applied to the other Indian groups in Florida, although the Indians always viewed themselves as belonging to different tribes. Other groups in Florida at the time of the Seminole Wars were the Yuchi Indians, also called "Spanish Indians" because they were believed to be descended from the Calusa Indians, and Rancho Indians, who lived in coastal fishing villages. Slaves entering Spanish Florida were basically free. The Spanish dignitaries even greeted the escaped slaves, allowed them to settle in their own small town (Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, or Fort Mose for short near San Agustin) and used them as militia to defend the latter town. Other escaped slaves became part of various “Seminole” groups, sometimes as slaves, but sometimes also as free tribe members. The conditions of slavery were much easier among the Indians than in the English colonies. Joshua Reed Giddings wrote in 1858: “They kept their slaves on a level between submission and freedom; the slave usually lived with his own family and passed his time as he pleased; he paid his master a small amount of corn or other vegetables every year. These slaves viewed subservience among whites with the greatest degree of horror. ”While most of the Fort Mose slaves went to Cuba with the Spaniards when they left Florida in 1763, those who lived with the Indian tribes remained and slaves continued to flee Carolina and Georgia to Florida. The blacks who joined the Seminoles were integrated into the tribes, learned the Seminole languages, took on their clothing, and married Seminole women. Some of these Black Seminoles even became important tribal leaders.

Early political and military conflicts

During the American Revolutionary War , the British - who ruled Florida - recruited Seminoles to carry out raids against border settlements in Georgia. This event made the Seminoles enemies of the newly formed United States of America. Florida was returned to Spain as part of the 1783 Peace Treaty that ended the War of Independence. Spain's rule over Florida was not very effective, with only small garrisons at San Agustin, San Marcos, and Pensacola . The border between Florida and the United States was not controlled. Miccosukees and other Seminole groups were still occupying villages on the American side of the border and illegal American settlers were invading Florida.

Florida had been divided into east and west Florida by the British in 1763, and the Spanish maintained that division when they regained Florida in 1783. West Florida stretched from the Apalachicola River to the Mississippi . This, along with their Louisiana possessions , gave the Spanish control of all of the lowlands between the rivers that drain the areas west of the Appalachians . Together with the belief that expansion was the inevitable fate ( Manifest Destiny ) of the USA, the USA also wanted to buy Florida so that it could trade freely on the rivers in the west and thus not use Florida as a base for an invasion by a European power could serve.

The purchase of Louisiana in 1803 gave the United States control of the Mississippi Estuary, but large areas of Georgia, Alabama , Tennessee, and Mississippi drain through rivers that flow into the Gulf of Mexico through west or east Florida . The US claimed the purchase included land west of the Perdido River, while Spain claimed that western Florida extended as far as the Mississippi. Finally, the citizens of Baton Rouge set up their own administration, captured the Spanish fort there and applied for protection from the USA. President James Madison commissioned William CC Claiborne , governor of the Orleans Territory , to conquer west Florida from the Mississippi to the Perdido River. Claiborne, however, only occupied the area west of the Pearl River (today's eastern border of Louisiana). Then Madison sent George Mathews to negotiate with Florida. When the offer to cede the remainder of the disputed area of West Florida to the United States was rejected by the West Florida Governor, Mathews traveled to East Florida to instigate a rebellion similar to that which had taken place in Baton Rouge. However, since the residents of East Florida were satisfied with their previous status, a group of fighters (who were promised free land) was set up in Georgia. In March 1812 these "patriots" captured Fernandina with the help of gunboats of the US Navy . The conquest of Fernandina was originally approved by President Madison, which he later denied. However, the "patriots" did not succeed in conquering the Castillo de San Marcos near San Agustin, and the beginning war with Great Britain finally ended the American advance into East Florida. In 1813, however, American forces captured Mobile (then still known as Mauvila, also spelled Maubila) from the Spanish.

Before the "Patriot Army" withdrew from Florida, it was attacked by the Seminoles, allied with the Spanish. These attacks reinforced the Americans' belief that the Seminoles were their enemies. The presence of black Seminoles in the fighting heightened fears of a slave rebellion among Georgia "patriots". In September 1812, a group of Georgia fighters attacked Seminoles on the Alachua Prairie, but the Seminoles suffered only minor losses. In 1813, a larger force drove the Seminoles out of their villages on the Alachua prairie and killed or drove away thousands of cattle.

First Seminole War

Creek War and Negro Fort

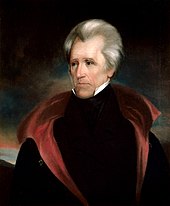

The next big event that had an impact on the Seminoles in Florida was the Creek War of 1813-14. Andrew Jackson became a national hero after defeating the Creek in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814 . After his victory, Jackson imposed the Treaty of Fort Jackson on the Creek, which included large losses of land in southern Georgia and central and southern Alabama for the Creek. As a result, many of the Creek left Alabama and Georgia and migrated to Florida.

Also in 1814, during the British-American War , British units landed in Pensacola and other places in West Florida and began to recruit Indian allies. In May 1814, a British unit advanced to the mouth of the Apalachicola River and handed firearms to the Seminoles, Creek and runaway slaves living there. Then the British advanced up the river and began building a fort at Prospect Bluff. After the British and their Indian allies were repulsed in their attack on Mobile, an American army under General Jackson drove the British out of Pensacola. However, work on the fort at Prospect Bluff continued. When the war ended, the British forces left West Florida except for Major Edward Nicholls of the Royal Marines . He oversaw the supply of cannons, muskets and ammunition to the fort and told the Indians that the Treaty of Ghent would guarantee the recovery of all Indian territories lost during the war, including the lands of the Creek in Georgia and Alabama. However, the Seminoles were not interested in maintaining a fort and returned to their villages. Before leaving Florida in the summer of 1815, Major Nicholls suggested that the runaway slaves in that area take over the fort. Word quickly got around in the area, and the fort was soon only called "Negro Fort" by whites in the southern United States. They saw the existence of this fort as a dangerous incentive for their slaves to flee or revolt.

Andrew Jackson wanted to eliminate Negro Fort, but it was on Spanish territory. In April 1816, he informed the governor of West Florida that if he did not eliminate Negro Fort, he would. The governor replied that he did not have the necessary equipment to take the fort. Jackson then authorized Brigadier General Edmund Pendleton Gaines to look after the fort. Gaines ordered Colonel Duncan Lamont Clinch to build a fort (Fort Scott) on the Flint River on the northern Florida border. Gaines then made clear his intention to supply Fort Scott from New Orleans via the Apalachicola River, which meant that the transports would have to pass through Spanish territory and Negro Fort. Gaines explained to Jackson that using the Apalachicola River to supply Fort Scott would allow the U.S. Army to keep an eye on the Seminoles and Negro Fort, and if the fort fired at the supply boats it would give the Americans an opportunity to to destroy the fort.

A supply fleet for Fort Scott reached the Apalachicola in July 1816. Clinch marched down the river with more than 100 American soldiers and about 150 Creek. The supply fleet met Clinch at Negro Fort and the two gunboats of the fleet took up their positions on the river opposite the fort. The blacks at the fort fired their cannons at the US soldiers and their Creek allies, but they had no training in aiming the cannons. The Americans fired back from their gunboats. The ninth cannon shot, a "hot shot" (a cannon ball was heated to a red glow) landed in the fort's powder magazine. The following explosion could be heard 160 kilometers away in Pensacola, razing the fort to the ground. Of the approximately 320 people in the fort, around 250 died instantly, with many others succumbing to their injuries shortly afterwards. After the fort was destroyed, the US Army withdrew from Florida, but American looters and outlaws continued to raid the Seminoles, killing Indians and stealing their cattle. Reports of the murders and thefts by the white settlers spread among the Seminoles and led to retaliatory attacks, in particular livestock being stolen back from settlers. On February 24, 1817, the Seminoles murdered Mrs. Garrett, who lived in Camden County , Georgia, and her children, one three years old and the other just two months.

Fowltown and the Scott Massacre

Fowltown was a Miccosukee village in southwest Georgia, about 15 miles east of Fort Scott. Neamathla, the chief of Fowltown got into a dispute with the commander of Fort Scott over control of an area east of the Flint River that Neamathla claimed for the Micossukee. This southern Georgia land was ceded to the Creek in the Treaty of Fort Jackson, but the Micossukee did not consider themselves to be a Creek and therefore not bound by the Treaty, stating that the Creek had no right to give up Miccosukee land . In November 1817, General Gaines dispatched 250 men to arrest Neamathla. The first attempt was repulsed by the Miccosukee, but the next day, November 22nd, 1817, they were evicted from their village. Some historians date the beginning of the First Seminole War to this attack on Fowltown. David Brydie Mitchell , former Georgia governor and Indian commissioner, said in a report to Congress that the attack on Fowltown sparked the First Seminole War.

A week later, a supply boat for Fort Scott on Apalachicola was attacked by Seminoles. There were about 40 to 50 people on the boat, including about 20 sick soldiers, seven wives of soldiers and possibly a few children (There are reports of 4 children killed by the Seminoles, but these were not mentioned in previous reports of the massacre mentioned and their presence could not be confirmed.). Most of the boat occupants were killed. One woman was captured and six survivors made it to the fort.

General Gaines initially had orders not to invade Florida, but this was later changed to allow short crossings to Florida. When news of the Apalachicola massacre reached Washington, DC , Gaines was ordered to invade Florida and pursue the Indians, but was not to attack any Spanish facilities. However, Gaines had already left for East Florida to deal with pirates who had taken Fernandina. Then Andrew Jackson was ordered by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun to invade Florida.

Jackson's campaign against Florida

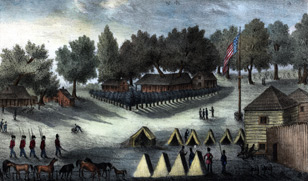

Jackson gathered his forces at Fort Scott in March 1818; it included 800 regular US Army soldiers, 1,000 Tennessee volunteers , 1,000 Georgia militiamen, and approximately 1,400 Lower Creek warriors. On March 13, Jackson's army invaded Florida and moved down the Apalachicola. When they reached the area where Negro Fort had stood, Jackson had his men build a new fort, Fort Gadsden . The army then fanned out to destroy the Miccosukee villages around Lake Miccosukee. On March 31, the Tallahassee Indian settlement was burned down and the Miccosukee settlement was captured the following day. More than 300 Indian huts were destroyed. After that, Jackson turned south and reached San Marcos on April 6th.

In San Marcos, Jackson captured the Spanish fort. There he met Alexander George Arbuthnot, a Scottish trader from the Bahamas . He traded with Indians in Florida and had written several letters to British and American officials on Indian affairs. There were also rumors that he had sold weapons to the Indians and equipped them for war. He probably actually sold firearms, since the Indians' main trade was deer hides and they needed firearms to hunt the deer. Two Native American leaders, Josiah Francis and Homathlemico, were arrested as they approached a British-flagged American ship anchored off San Marcos. As soon as Jackson arrived in San Marcos, the two were taken ashore and hanged.

Jackson then left San Marcos to attack villages along the Suwannee River that were mostly populated by runaway slaves. On April 12, the army found an Indian village on the Econfina River . Around 40 Indians were killed and around 100 women and children captured. In the village they found Elizabeth Stewart, the woman who had been kidnapped during the attack on the supply boat on the Apalachicola in November of the previous year. The army found the villages on Suwannee empty, however, and were attacked by Black Seminoles for almost the entire march. At the same time, Robert Ambrister, a Royal Marine and self-proclaimed British agent, was arrested by Jackson's soldiers. Having destroyed the main Seminole and black villages, Jackson proclaimed victory and sent the Georgia and Lower Creek militia home. The remaining army returned to San Marcos.

A military tribunal was held in San Marcos, accusing Ambrister and Arbuthnot of supporting the Seminoles and inciting them to go to war against the United States. Ambrister submitted to the mercy of the court, while Arbuthnot protested his innocence and insisted that he was only trading legally. The tribunal sentenced both men to death, but changed Ambrister's sentence to 50 lashes and one year of forced labor. Jackson modified the sentence so that Ambrister was also sentenced to death. Ambrister was shot on April 29, 1818, and Arbuthnot was hanged from the yard of his own ship.

Jackson left a garrison in San Marcos and returned to Fort Gadsden. Jackson first reported that everything was peaceful and that he would retire to Nashville , Tennessee. Later, however, he reported that the Indians were gathering, where they were fed and equipped by the Spaniards, so he left Fort Gadsden on May 7, 1818 with 1,000 men and made his way to Pensacola. The governor of west Florida protested, stating that most of the Indians in Pensacola were women and children and that the men were unarmed, but Jackson didn't stop that. When Jackson reached Pensacola on May 23, the governor withdrew to Fort Barrancas with the 175-strong Spanish garrison and left the city of Pensacola to Jackson. Both sides then fought a gun battle for a few days before the Spaniards surrendered to Jackson on May 28 at Fort Barrancas. Jackson installed Colonel William King as military governor in west Florida and returned home.

Effects

There were international entanglements over Jackson's warfare. US Secretary of State John Quincy Adams had only just started negotiations with Spain to buy the Florida colony. Spain now protested against the invasion and conquest of West Florida and suspended negotiations. However, Spain did not have the means to take action against the USA and retake West Florida, so Adams simply let Spain protest before finally, in a letter to Spain, blamed the British, the Spanish and the Indians for the war. In the letter he also apologized for the conquest of West Florida and stated that the conquest of Spanish territory was not in accordance with American policy and offered to return San Marcos and Pensacola. Spain accepted this and eventually resumed negotiations on the sale of Florida. Feeling that this would strengthen his diplomatic status , Adams defended Jackson's actions as necessary and demanded that Spain either better control the residents of East Florida or cede East Florida to the United States. Finally, an agreement was reached in which Spain ceded eastern Florida to the USA and renounced all claims to western Florida.

Britain protested the execution of two British citizens who had never entered US territory. Voices were raised in Britain to seek redress and retaliate. America already feared another war with Great Britain. However, given the importance of the US to the UK economy, Britain chose to prioritize good relations.

There were also discussions in America about the executions. Congressional committees held hearings on the Ambrister and Arbuthnot tribunals. While most Americans supported Jackson's actions, some were also concerned that he might become an American Napoleon . When Congress convened again in December 1818, draft resolutions were introduced condemning Jackson's actions. Jackson was too popular, however, and so the applications failed, but the executions of Ambrister and Arbuthnot left a lifetime "smudges" in Jackson's biography, which did not prevent him from later becoming President of the United States.

First interwar period

Spain gave Florida to the United States in 1821 under the Adams-Onís Treaty . The administration was built up gradually. General Andrew Jackson was named military governor of Florida in March 1821, but did not arrive at Pensacola until July of that year. He resigned from the post in September and returned home in October, so he had held this post for just 3 months. His successor, William P. Duval , was not appointed until April 1822. But before the end of the year he made an extended home visit to Kentucky . Other offices have suffered from similar irregularities and long absences from office holders.

But the Seminoles were still a problem for the new government. In the spring of 1822, Captain John R. Bell, Florida Provisional Secretary and Temporary Seminole Commissioner, made an estimate of the number of Seminoles. He reported 22,000 Indians and 5,000 slaves held by the Indians. He estimated that two thirds of the Indians were refugees from the Creek War and thus (according to US views) without a claim to land in Florida. Native American settlements have been identified in the Apalachicola area, along the Suwannee, thence southeast to the Alachua Prairie, and finally southwest to just north of Tampa Bay .

Florida officials have been concerned about the situation with the Seminoles from the start. Until a treaty on a reservation was signed, the Indians could not be sure where to sow and reap, and they had to deal with white illegal settlers who simply occupied their land. There was no system of licensed dealers, and the unlicensed dealers mainly supplied the Seminoles with liquor. Due to the frequent lack of government officials in Florida, meetings with the Seminoles were often canceled, postponed, and sometimes only held to arrange a location and date for a new meeting.

The Moultrie Creek Treaty

In 1823 the government finally decided to settle the Seminoles on a reservation in central Florida. A meeting to negotiate the relevant contract was set for September 1823 at Moultrie Creek, south of St. Augustine. About 425 Seminoles attended the meeting and chose Neamathla as their chief negotiator. The terms of the contract negotiated there provided that the Seminoles submitted to the protection of the USA and gave up all claims to land in Florida, in exchange they would receive a reservation with 16,000 km². The reservation would be in central Florida starting from north of what is now Ocala south to a line level with the south end of Tampa Bay. The borders were to be inland on both sides to prevent contact between the Indians and coastal traders from the Bahamas and Cuba. However, Neamathla and five other chiefs were allowed to keep their villages on Apalachicola.

In the Moultrie Creek Treaty , the US government was obliged to protect the Seminoles as long as they were peaceful and law-abiding. The government should deliver agricultural implements, cattle and pigs to the Seminoles, compensate them for the relocation to the reservation and the losses involved, and provide the Seminoles with an annual ration of provisions until the Seminoles could sustain themselves through their first harvest. The government should also pay the Seminoles $ 5,000 annually for 20 years, and also provide maintenance for an interpreter, school, and blacksmith for 20 years. In return, the Seminoles had to agree to the construction of roads through their reservation and had to seize any refugee or runaway slave who was in their area and extradite them to the jurisdiction of the United States.

The implementation of the contract was delayed again and again. Fort Brooke with 4 infantry companies was built in the spring of 1824 on the site of what is now Tampa Bay to show the Seminoles that the government was serious about relocating to the reservation if necessary. In June, James Gadsden , the author of the contract and the person responsible for its implementation, reported that the Seminoles were dissatisfied with the contract and wanted to renegotiate it. The fear of a new war spread. In July, Governor DuVal mobilized the militia and ordered the Tallahassee and Miccosukee chiefs to meet with him in St Marks. At this meeting he ordered the Seminoles to move to the reservation by October 1, 1824 at the latest.

The Seminoles slowly moved to the reservation despite occasional conflicts with whites. Another fort, Fort King , was built near the reservation authority, in what is now Ocala, and in the spring of 1827 the army reported that all Seminoles had moved to the reservation and that Florida was peaceful. This peace lasted 5 years, during which there were repeated calls to relocate the Seminoles to areas west of the Mississippi. The Seminoles refused to accept such demands and also the suggestions that they should join the Creek (supposedly) related to them. Most whites viewed the Seminoles as simply creeks who had recently immigrated to Florida, while the Seminoles viewed Florida as their ancestral home and denied any connection with the Creek.

The problem of runaway slaves also led to repeated disputes between whites, slave hunters and Seminoles over ownership of slaves. New plantations in Florida increased the number of slaves who repeatedly fled to the Seminoles. Concerned about the threat of an Indian uprising or a slave rebellion, Governor DuVal requested additional federal troops for Florida. Instead, however, Fort King was closed in 1828. The Seminoles, on the other hand, did not find enough food at this time and the yields from hunting in the reserve continued to decline, which is why more and more Seminoles were leaving the reserve. Also in 1828, Andrew Jackson, the old enemy of the Seminoles, was elected President of the United States. In 1830, the Indian Removal Act finally passed Congress. Any problems with the Seminoles should be resolved by relocating them to areas west of the Mississippi.

Payne's Landing Contract

In the spring of 1832, the reservation's Seminoles were asked to report to Payne's Landing on the Ocklawaha River . The treaty negotiated there required the Seminoles to relocate west if suitable land was found there. They should settle on the Creek Reservation and become part of the Creek Tribe. The delegation of seven chiefs who were to inspect the area of this new reserve did not leave the reserve until October 1832. After roaming the reservation for several months and speaking to Creek, who had already been relocated there, the seven chiefs signed a declaration on March 28, 1833 confirming that the new land was acceptable. After their return to Florida, however, most of the chiefs revoked this statement, claiming that they had not signed the treaty or had been forced to sign it and that they had no authority to decide on behalf of all the tribes and groups on the reservation. The inhabitants of the villages near Apalachicola were more easily persuaded and relocated in 1834.

The US Senate ratified the Payne's Landing Treaty in April 1834. The treaty gave the Seminoles three years to relocate to the areas west of the Mississippi. The government interpreted the three-year period beginning in 1832 and expected the Seminoles to be relocated by 1835. Fort King was reactivated in 1834. A new Seminole commissioner, Wiley Thompson , was also appointed in 1834, with the task of persuading the Seminoles to relocate. He gathered the chiefs at Fort King in October 1834 to negotiate with them about moving west. The Seminoles explained to him that they had no intention of going west and that they were not bound by the Payne's Landing treaty. Thompson then requested reinforcements for Fort King and Fort Brooke, reporting that "after receiving the annual grant, the Indians bought an unusually large amount of gunpowder and lead." General Clinch Washington also warned that the Seminoles were not planning to to relocate, and that he needed more troops to force them to do so. In March 1835, Thompson again called the chiefs to a meeting to read them a letter from Andrew Jackson. In that letter, Jackson said, "If you ... refuse to relocate, the commanding officer is empowered to remove you by force." The chiefs asked for 30 days to respond. A month later, the Seminole chiefs told Thompson that they would not relocate west. Thompson and the chiefs began to argue, and eventually General Clinch even had to intervene to avoid bloodshed. Ultimately, eight chiefs agreed to relocate west, but asked for a stay until the end of the year, which Thompson and Clinch agreed to do.

However, five of the main Seminole chiefs had not consented, including Micanopy of the Alachua Seminoles. Therefore, Thompson declared that these chiefs had been removed from their position. When relations with the Seminoles deteriorated dramatically, Thompson banned the sale of firearms and ammunition to them. Osceola , a young Seminole, was particularly angry about this spell, because he thought it would equate him with slaves and he said: “The white man should not blacken me. I'll make the white man red with blood and then blacken him in the sun and rain ... and the buzzard will live on his flesh. ”Even so, Thompson declared that Osceola was a friend and gave him a rifle. However, later, when Osceola continued to cause problems, he had him locked up at Fort King for one night. The next day, to ensure his release, Osceola agreed to obey the Payne's Landing contract and persuade his followers to do so.

The situation got worse. On June 19, 1835, a group of whites looking for their cattle found a group of Indians around a campfire. They were busy cooking the remains of a cattle that they claimed was one of their herd. The whites were disarming and whipping the Indians when two more Seminoles came along and opened fire on the whites. Three whites were wounded, one Seminole killed and one wounded. This incident became known as the "Skirmish at Hickory Sink". After the Seminoles complained to Commissioner Thompson and received no satisfactory answer, the Seminoles became even more convinced that their complaints about unfair behavior by the white settlers were not heard. Believing that he was responsible for the Hickory Sink incident, among other things, the Seminoles killed Private Kinsley Dalton (after whom Dalton , Georgia was named), who was delivering mail from Fort Brooke to Fort King, in August 1835 .

In November 1835, Seminole chief Charley Emathla sold his cattle to Fort King to prepare himself and his people for the journey to Fort Brooke and westward from there. This was seen as treason by other Seminole chiefs, as they had agreed at a meeting a few months earlier that any chief who sold his cattle would be punished with death. Osceola met Emathla on his way back to the village and killed him, then scattered the money from the trade over his body.

Second Seminole War

When it was finally assumed that the Seminoles would oppose the relocation, Florida began to prepare for war. Two companies with a total of 108 men under the command of Major Francis L. Dade were dispatched from Fort Brooke to reinforce Fort King. On December 28, 1835, the Seminoles attacked this unit and destroyed it. Only two soldiers made it back to Fort Brooke, one of whom later died of his wounds. For the next several months, Generals Clinch, Gaines, and Winfield Scott, and Territory Governor Richard Keith Call , led larger troops through the area in unsuccessful attempts to pursue the Seminoles. In the meantime, the Seminoles struck across the state, attacking isolated farms, settlements, plantations and army facilities and even burned the lighthouse on Key Biscayne (Cape Florida Lighthouse). Supply problems and a high number of illnesses (especially in summer) forced the army to abandon several forts.

Andrew Jackson wasn't the only American tired of war. Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock was among those who found the remains of the Dade group in February. In his newspaper he wrote a lurid account of the discovery before going on to state his own opinion on the conflict: “The government is wrong, and that is the main reason for the continued opposition from Indians who honor their country against our efforts to to enforce a dubious treaty. The natives did everything possible to avoid war, but they were forced to do so by the tyranny of our government. "

On November 21, 1836, the Seminoles fought American troops in the Battle of Wahoo Swamp, killing David Moniac, the first West Point graduate who was, at least partially, of Indian descent. Success in this important battle earned the Seminoles a great deal of confidence and belief that they could defend their territory in the Florida wilderness against the white settlers and the Creek. Towards the end of 1836, Major General Thomas Jesup was appointed commander of American troops for this theater of war. He changed the war tactics. Instead of sending large units to field the Seminoles in a field battle, he focused on exhausting the Seminoles. To do this, however, he needed a large force, which he got. After all, Jesup had 9,000 soldiers under his command. About half of them were militiamen and volunteers. He was also responsible for a brigade of Marines and units of the Navy, as well as the River Navy, who patrolled the coasts and rivers.

In January 1837 the fortunes of war turned. Many Seminoles and Black Seminoles were killed or captured in numerous skirmishes. At the end of January, some Seminole chiefs sent a messenger to Jesup, and a ceasefire was arranged. In March, some chiefs (including Micanopy) signed a "capitulation", in which it was agreed that the Seminoles, accompanied by their allies, would move "their negroes and their" bona fide "property" to the west. At the end of May, many chiefs, including Micanopy, complied. However, two important leaders, Osceola and Sam Jones (also called: Abiaca, Ar-pi-uck-i, Opoica, Arpeika, Aripeka, Aripeika) had not surrendered and were known to vehemently oppose relocation. On June 2, 1837, these two leaders, along with 200 followers, stormed the poorly guarded detention center at Fort Brooke and led away 700 surrendered Seminoles. The war was on again, and Jesup never again trusted the word of an Indian. At Jesup's orders, Brigadier General Joseph Marion Hernández commanded an expedition that captured some Seminole leaders , including Coacoochee (Wildcat), Osceola, and Micanopy, when they appeared to negotiate under a white flag. Coacoochee and a few other prisoners managed to escape Fort Marion near St. Augustine, but Osceola did not go with them. He later died in captivity, possibly of malaria.

Jesup organized a kind of driven hunt with several columns, the aim of which was to drive the Seminoles further south. On Christmas Day 1837, Colonel Zachary Taylor's column of 800 men met around 400 Seminoles on the northern coast of Lake Okeechobee . The Seminoles were led by Sam Jones, along with Alligator and the recently escaped Coacoochee. They had tactically favorable surrounded in marshland on a tree island from cutting rushes positioned. Taylor's troop entered an elongated island of trees and had half a mile of swamp in front of them, with Lake Okeechobee beyond. The rushes stood up to 5 feet high there, and the mud and water were 3 feet deep. Horses were absolutely useless there. Apparently the Seminoles wanted to use this area as a battlefield. They had mowed the grass for an open field of fire and notched the trees so they could aim their rifles. Their scouts sat in the trees and could watch every movement of the incoming troops. At about 12:30 p.m., when the sun was at its zenith and not even a breeze, Taylor led his soldiers into the middle of the swamp. His plan was to attack the Indians directly instead of encircling them. All of his men marched on foot, the front line being made up of volunteers from Missouri . As soon as they were within range, the Indians opened fire. The volunteer unit was blown up and its leader Colonel Gentry was fatally wounded, leaving them without leadership. They fled back through the swamp. The fighting in the swamp was grueling for five companies of the Sixth Infantry; all but one of the officers fell, and most of their foot soldiers died or were wounded. When a small part of the regiment withdrew in order to regroup, it was found that only 4 men from these companies were unharmed. The Seminoles were eventually driven out of the swamp and escaped across the lake. Taylor had 26 dead and 112 wounded, the Seminoles 11 dead and 14 wounded. Even so, the Battle of Lake Okeechobee was hailed as a great victory for Taylor and for the army.

In late January, Jesup's troops encountered a large cluster of Seminoles east of Lake Okeechobee. The Seminoles were originally positioned on an island of trees here, too, but cannon and rocket fire drove them away from there. They took up position again behind a broad river. The Seminoles eventually dispersed after inflicting more casualties than they suffered. This is how the Battle of Loxahatchee ended. In February 1838, the Seminole chiefs Tuskegee and Halleck Hadjo Jesup approached and promised they would stop fighting if they were allowed to stay south of Lake Okeechobee. Jesup liked the proposal, but had to write to Washington for permission. The chiefs and their followers camped near the army while they waited for the answer. When the Minister of War rejected the proposal, Jesup captured the 500 Indians in the camp and sent them west.

In May, Jesup's request to resign from command was granted and Zachary Taylor was given supreme command of the Florida armed forces. With fewer troops, Taylor concentrated on keeping the Seminoles out of northern Florida by building smaller posts at intervals of 30 km, which were connected by a network of roads. The following winter was pretty calm, incidents and skirmishes continued, but no major actions. Support for the war waned in Washington and across the country. Many people thought the Seminoles deserved to stay in Florida. The war was by no means over and extremely expensive. President Martin Van Buren dispatched the commanding general of the Army, Alexander Macomb, to negotiate a new treaty. On May 19, 1839, Macomb announced that an agreement had been reached with the Seminoles. The Seminoles would stop fighting and be assigned a reservation in southern Florida.

During the summer the agreement seemed to hold up. On July 23, however, 150 Indians attacked a trading post on the Caloosahatchee River, which was guarded by 23 soldiers under the command of Colonel William S. Harney. Some of the soldiers, including Harney, escaped to the river and escaped on boats, but the remaining soldiers and several civilians from the trading post were killed. Many accused the '' Spanish '' Indians, led by Chakaika, of the attack. But some also suspected Sam Jones and his miccosukees, who made the deal with Macomb. Sam Jones promised to hand over those responsible for the attack to Harney within 33 days. Before that time was over, however, two soldiers visiting Sam Jones' camp were killed.

The army was now using new tactics. So attempts were made to track down the Indians with bloodhounds, but with poor results. Taylor's system of posts and patrols kept the Seminoles moving but could not drive them out either. In May 1839, Zachary Taylor's transfer was approved. He had served longer than any other commander in the Seminole War and was replaced by Brigadier General Walker Keith Armistead. Armistead immediately went on the offensive. The army searched the hidden camps of the Seminoles, burned the fields and drove away the horses, cattle and pigs. By the middle of summer, the army had destroyed around 2 km² of the Seminole fields.

The navy also played an important role in the war, sailors and marines went up the rivers and they sailed the Everglades . In late 1839, Navy Lt. John T. McLaughlin handed command of a combined Navy-Army force in Florida. McLaughlin established his headquarters on Tea Table Key Island. From December 1840 to mid-January 1841, McLaughlin's troops crossed the Everglades in canoes from east to west, making them the first whites to do so.

Indian Key

Indian Key is a small island in the upper Florida Keys . In 1840 it was the administrative seat of Dade County and wrecks were cannibalized in the harbor. Early in the morning of August 7, 1840, a large group of "Spanish" Indians crept onto the island. A man accidentally spotted the Indians and sounded the alarm, so 40 of the approximately 50 residents were able to escape, the rest were killed. Among the dead was Dr. Henry Perrine, former US Consul in Campeche , Mexico , who waited on Indian Key until it was safe to take possession of his 93 km² mainland property that Congress had given him.

At the naval base at Tea Table Key there were only a medical doctor and his patients, who were protected by five sailors under the orders of a cadet. This small group mounted a number of cannons on barges and used them to attack the Indians on Indian Key. The Indians fired back with cannons stationed on the island. However, the recoil of the cannons on the barges was so strong that the sailors were thrown into the water, so that they had to retreat. The Indians eventually burned down the buildings on Indian Key after thoroughly looting them. In December 1840, Colonel Harney, led by 90 men, found Chakaika's camp deep in the Everglades. Chakaika was killed and some men in his group were hanged.

The war is subsiding

Armistead had $ 55,000 to bribe chiefs and get them to surrender. Echo Emathla, the chief of Tallahassee, surrendered, but most of the Tallahassee under Tiger Tail resisted. Coosa Tustenuggee finally accepted US $ 5,000 and surrendered with his 60 men. Lesser chiefs received $ 200 and each warrior received $ 30 and a rifle. By the spring of 1841 Armistead had sent 450 Seminoles west. Another 236 were in Fort Brooke waiting to be removed. Armistead estimated that 120 warriors had been moved west during his tenure and that there were no more than 300 warriors left in Florida.

In May 1841 Armistead was replaced by Col. William Jenkins Worth. Since the war was now unpopular among the population and in Congress, Worth had to accept cuts. Almost 1,000 civil servants in the army were dismissed and smaller commands were merged. Worth ordered "search and destroy" missions, which drove the Seminoles almost entirely from northern Florida.

The continued pressure from the army had an effect. More groups of Seminoles surrendered in order not to starve to death. Others were captured as they approached to negotiate, including a second time Coacoochee. A generous bribe secured Coacooche's cooperation in persuading more Indians to give up.

After Colonel Worth recommended in the spring of 1842 that the remaining Seminoles be left alone, he received permission to grant them an informal reservation in southwest Florida and to declare the war over, which he did on August 14, 1842. In the same month, Congress passed the Armed Occupation Act, which promised settlers free land if they tilled the land and managed to defend themselves against the Indians. In late 1842, the remainder of the Indians who lived outside the reservation in southwest Florida were arrested and taken west. By April 1843, the army presence in Florida was reduced to just one regiment. In November 1843, Worth reported that the only American Indians left in Florida were 95 men and approximately 200 women on the reservation, and that these would no longer pose a threat.

Aftermath

The Second Seminole War had cost approximately US $ 40,000,000. More than 40,000 soldiers, militiamen and volunteers had served in the war. This Indian war cost the lives of 1,500 of them, most of them as a result of diseases and epidemics, and there are also many Indian deaths. It is estimated that around 300 Army, Navy and Marines men were killed, along with 55 volunteers. There is no precise information about the number of Seminole warriors killed. A large number of Seminoles died of disease and starvation in Florida on their way west and after arriving in the west. An unknown, but apparently no small number, of white civilians were killed by the Seminoles during the war.

Second interwar period

Peace had returned to Florida. Most of the Indians stayed in the reservation. Groups of ten or more frequented Tampa to trade and get drunk. Looters continued to approach the reservation, however, and so President James Polk had to create a 30 km wide buffer zone around the reservation. No land was allowed to be claimed in the buffer zone, no one was granted real estate in the buffer zone, and the US Marshal had instructions to remove any illegal settler immediately upon request. In 1845, Thomas P. Kennedy converted his fishing supplies shop on Pine Island into an Indian trading post. The job did not go very well, however, as whites who sold whiskey to the Indians persuaded them that they would be arrested and sent west if they visited Kennedy's shop.

The Florida government put pressure on the removal of all Indians from Florida. For their part, the Indians tried to limit their contacts with the whites as much as possible. In 1846, Captain John T. Sprague was appointed Indian Commissioner in Florida. He had great difficulty getting the chiefs to meet him at all. They were extremely suspicious of the Army as many of the chiefs had also been captured under a white flag. But he managed to meet with all the chiefs in 1847 while investigating the raid on a farm. He estimated that there were 120 warriors at the time, including 70 Seminoles in Billy Bowleg's group, 30 miccasokees in Sam Jones' group, 12 creeks in Chipco's group, plus 4 Yuchi and 4 Choctaws. In addition, he estimated 100 women and 140 children.

Indian attacks

The Pine Island trading post was burned to the ground in 1848, and in 1849 permission was given to Thomas Kennedy and his new partner, John Darling, to open a new post on Paynes Creek (a tributary of the Peace River). A group of Indians lived outside the reservation at the time. Its members were therefore also called the “outsiders”. They consisted of 20 warriors under the leadership of Chipco, composed of 12 miccosukees, 6 Seminoles, a creek and a yuchi. On July 12, 1849, four warriors of this group raided a farm on the Indian River, just north of Fort Pierce, killing a man and wounding another man and woman. News of this raid caused large parts of the population on the east coast of Florida to flee to St. Augustine. On July 17, 1849, five "outsiders" (the four from the farm robbery plus one other) raided Kennedy's trading post. Two shop workers, including Captain Payne, were killed and another worker and his wife were wounded trying to hide their child.

The US Army was unable to take care of the Indians. She had only a few men stationed in Florida and had no means to move them quickly to protect settlers and farms or to confront the Indians. However, the War Department began rearming and set up two companies of volunteers under the command of Major General David Twiggs to protect the settlers . Captain John Casey, who was supposed to be relocating the Indians west, managed to organize a meeting between General Twiggs and a couple of Indian chiefs in Charlotte Harbor. At this meeting, Billy Bowlegs, with the consent of the other chiefs, promised to hand over the five men in charge to the Army within thirty days. On October 18, Bowlegs handed three of the men over to Twiggs, along with the severed hand of another who had been killed in an attempt to escape. The fifth man was captured, but escaped.

However, after Bowlegs surrendered the three killers, General Twiggs, to their disappointment, told the Indians that he had been ordered to remove them from Florida. The government envisaged three measures to carry out the removal. The army in Florida was increased to 1,500 men. US $ 100,000 was provided to encourage the Indians to relocate. Eventually, a delegation of Seminole chiefs was brought in from Indian territories to the west to negotiate with the chiefs in Florida. A Miccosukee sub-chief, Kapiktoosootse, agreed to lead his people west. In February 1850, 74 Indians embarked for New Orleans . They were paid a total of US $ 15,953 as a bribe and in compensation for the belongings left behind in Florida. However, there were incidents that worsened relations. Two miccosukees who had come to trial at the same time as Kapiktoosootse were shipped to New Orleans without her consent. In March, a mounted unit of the 7th Infantry penetrated deep into the reservation. Then the remaining Indians broke off contact. In April General Twiggs had to report to Washington that there was no hope of persuading any more Indians to move.

In August 1850, an orphan boy who lived on a farm in north central Florida was murdered by Indians. After numerous complaints, the war minister in Washington finally ordered the responsible Indians to be extradited, otherwise the president would hold the entire tribe accountable. Captain Casey managed to contact Bowlegs the following April. Bowlegs promised to extradite the guilty even though they were part of Chipco's group over which he had no authority. However, Chipco extradited three men as suspected murderers, who were then arrested when they appeared in Fort Myers for trial. In custody they protested, declared their innocence and asserted that Chipco had only extradited them because he didn't like them; however, others are responsible for the murder. Captain Casey believed them. The three men tried to escape, but were caught and then chained in the cell. She was later found hanged in her cell. One was found alive, but left hanging until he too died. It was noted in the community that the guard who chained the three of them, their brother's father-in-law, was one of those killed in the 1849 attack on the Darling store.

More Indian resettlements

In 1851 General Luther Blake was commissioned by the US Secretary of the Interior to move all of the Indians who remained in Florida to the west. He had already successfully relocated the Cherokee from Georgia and should now be able to do the same with the Seminoles. He was given funds to pay $ 800 for each man and $ 450 for each woman and child. He then went to Indian territory to find suitable interpreters before returning to Florida in March 1852. He penetrated deep into the Indian territories to track down Indian chiefs and by July had finally persuaded 16 Indians to go west. However, since Billy Bowlegs insisted on staying in Florida, Blake took Bowlegs and a few other chiefs with him to Washington. President Millard Fillmore presented Bowlegs with a medal, then he and three other chiefs were persuaded to sign a statement promising to leave Florida. The chiefs were then sent on a tour of Baltimore , Philadelphia and New York City . When the chiefs returned to Florida, they immediately revoked their statement. As a result, Blake was fired in 1853 and Captain Casey was again assigned with the Indian relocation.

In January 1851, the Florida Government had created the post of Florida Militia Commander and appointed Benjamin Hopkins. For the next two years, the militia tried to persuade those Indians who still lived outside the limits of the reservation to relocate. During this time, the militia only managed to capture one man, a few women and 140 pigs. An old Indian woman committed suicide when she was captured while her family escaped. The entire operation had cost the state $ 40,000.

Florida officials again urged the federal government to take action. Captain Casey continued trying to persuade Indians to move west, but was out of luck. He again sent Billy Bowlegs and others to Washington, but the chiefs refused to move. In August 1854, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis drafted a program to force the remaining Seminoles into submission or final battle. The plan included a trade embargo against the Indians, the surveillance and sale of land in southern Florida, and an increased army presence to protect the settlers. Davis said that if the Indians did not consent to the move, the army would force them to do so.

Third Seminole War

Increasing army presence and Indian attacks

As of 1855, there were about 700 soldiers in Florida. At the same time, the Seminoles decided to strike back and, in turn, launch attacks when the opportunity arose. Allegedly Sam Jones was the inventor of the plan, while Chipco is said to have rejected it. On December 7, 1855, First Lieutenant George Hartsuff, who had already led several patrols into the reservation, left Fort Myers with ten men and two cars. They found no Seminoles, but found a few cornfields and three abandoned Indian settlements, including Billy Bowlegs'. On the evening of December 19, Hartsuff told his subordinates that they would return to the fort the following day. When the men were loading the wagons and saddling their horses on December 20th, 40 Seminoles under Billy Bowlegs attacked them. Several soldiers were shot, including Hartsuff, who was able to hide. The Seminoles killed and scalped 4 soldiers, killed the mules, looted and eventually burned the wagons before escaping with the soldiers' horses. Seven soldiers, four of them wounded, made it back to Fort Myers.

When news of the attack reached Tampa, the citizens elected militia officers and organized vigilante groups. The newly formed militia marched into the Peace River valley, recruited more men and manned a few forts along the river. Governor James Broome began raising as many vigilantes as he could. Since the state of Florida had limited resources, he tried to persuade the army to accept as many volunteers as possible. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis accepted two infantry companies and three mounted companies, a total of 260 men. Governor Broome mobilized another 400 men from the state of Florida. Both the forces controlled by the US government and those controlled by the state were largely armed with voluntary donations. General Jesse Carter was appointed "Special Agent ... of no military rank" by Governor Broome to command the troops. Carter assigned half of the soldiers to the guard, so that only 200 men were available for patrols. A newspaper in Tampa noted at the time that patrols were preferably conducted in the open, which was easier for the horses but could be seen from a distance by the Seminoles.

On January 6, 1856, two men who had collected cycad stalks south of the Miami River were killed. The settlers in the area immediately fled to Fort Dallas and Key Biscayne. A group of around 20 Seminoles under Ocsen Tustenuggee attacked a group of woodcutters in the vicinity of Fort Denaud and killed 5 of the 6 men. Despite the militia units stationed there, the Seminoles also carried out raids on the coast south of Tampa. They killed a man and burned down a house in what is now Sarasota , before they took over Dr. Braden Castle on March 31, 1856. Joseph Braden in what is now Bradenton . "Braden Castle" itself was defended too well, however, so that they only captured 7 slaves and 3 mules. Because they were hindered by the prisoners and the looted property, the Seminoles could not move quickly. While they were taking a break at Big Charley Apopka Creek and were roasting a cow they had captured and slaughtered, they were tracked down by the militia. The militiamen killed two Seminoles and took back the slaves and mules from “Braden Castle”. The scalp of one dead Seminole was shown publicly in Tampa, the other in Manatee.

During April, army and militia units patrolled Florida and the reservation, but could not provide Seminoles. Only at Bowlegs Town was there a six hour battle in which 4 soldiers were killed and another 3 wounded before the Seminoles withdrew. The Seminoles continued to raid across the state. On May 14, 1856, 15 Seminoles raided Captain Robert Bradley's farm, killing two of his children, while Bradley shot a Seminole. Bradley was likely a target for killing Tiger Tail's brother during the Second Seminole War. On May 17, the Seminoles ambushed a motorcade in central Florida, killing three men. As a result, post and station service in and around Tampa was suspended until the militia could provide protection. On June 14, 1856, the Seminoles attacked a farm two miles from Fort Meade, Florida . All residents made it into the house and were able to hold out the Seminoles. The gunfire was heard in Fort Meade, whereupon 7 militiamen set out. Three of the militiamen were killed and two more wounded. More militiamen tried to track the Seminoles but were forced to surrender after a downpour soaked their gunpowder supplies. On June 16, a group of 20 militiamen surprised a group of Seminoles on the Peace River and killed some of them. The militiamen withdrew after their own losses of two dead and three wounded. Afterwards they proclaimed that they had killed up to twenty Seminoles, whereas the Indians admitted only 4 dead and 2 wounded. One of the dead, however, was Ocsen Tustenuggee, who was apparently also the only chief to lead settlement raids.

The citizens of Florida grew increasingly dissatisfied with the militiamen. There were complaints that the militiamen would pretend to patrol for 1–2 days and then return home to do field work. In addition, some of them would indulge in laziness, drunkenness, and theft. The officers were accused of unwilling to complete the necessary paperwork. But most importantly, the militia were unable to stop the raids on the settlers.

New strategy

Brigadier General William S. Harney returned to Florida in September 1856 as commander of federal troops. Remembering the lessons of the Second Seminole War, he again had the forts manned in a line through Florida and patrols deep into the Seminole area. He planned to push the Seminoles into the Big Cypress Swamp and the Everglades, believing the Seminoles could not survive there during the rainy season. He wanted to stop the Indians when they left their flooded retreat to cultivate fields in the dry land. Part of Harney's plan was also to use boats to get to islands and dry land in the swamps as well. At first, however, he made an attempt to negotiate with the Seminoles, but was unable to even establish contact with them. In early January 1857 he ordered his troops to actively pursue the Indians. Harney's plan hardly resulted in success and in April he and the Fifth Infantry were withdrawn and the riots after Kansas posted.

Colonel Gustavus A. Loomis replaced Harney as commander in Florida, but the withdrawal of the Fifth Infantry left him with only ten companies from the Fourth Artillery, which were later reduced to four. To this end, Loomis organized volunteers in boat associations who were given metal "alligator boats" that had been specially built for use in the swamps. Each boat could hold up to 16 men. These boat associations captured numerous Indians, mostly women and children. The regular soldiers, however, were far less successful. Several officers, including Captain Abner Doubleday , watched how easily the Seminole army patrols avoided. Doubleday attributed this to the fact that most of the soldiers were recently immigrant immigrants who did not know how to move about in the wilderness.

In 1857 ten companies of the Florida militia were taken over into the federal service, which was nearly 800 men by September. In November these forces captured nearly 18 women and children from Billy Bowleg's group. The troops also found and destroyed several villages and fields. On New Year's Day 1858, the troops began to advance into the Big Cypress Swamp and destroyed several settlements and fields there as well. An Indian delegation from the Indian territory also tried again to contact Bowlegs. Last year the Seminoles had finally been granted their own reservation in Indian territory, separate from the Creek. In addition, payments of $ 500 to each warrior (more for the chiefs) and $ 100 to each Indian woman were promised. On March 15, Bowlegs and Assinwar's group accepted the offer and headed west. On May 4, 163 Seminoles (including a few previously captured) were shipped to New Orleans. On May 8, 1858, Colonel Loomis declared the war over.

Aftermath

When Colonel Loomis declared the end of the Third Seminole War, it was believed that there were no more than a hundred Seminoles left in Florida. In December 1858 another attempt was made to ship the remaining Seminoles west. On February 15, 1859, two more groups with a total of 75 Seminoles surrendered and were resettled. However, there were still Seminoles in Florida after that. Sam Jones' group still lived in southeast Florida, inland from Miami and Fort Lauderdale. Chipco's group lived north of Lake Okeechobee and neither the army nor the militia could spot him. Individual Indian families lived scattered across the wetlands of southern Florida. However, since the war was officially over and the remaining Seminoles remained quiet, the militiamen were sent home and the regular army troops disarmed. All the forts that were built in the Seminole Wars were abandoned and soon stripped of any useful material by settlers. In 1862, the State of Florida contacted Sam Jones with a promise to help keep the Seminoles neutral in the Civil War. The state did not fulfill its aid pledges, but the Seminoles were also not interested in fighting another war. In the Florida constitution of 1868, at the instigation of the Republicans of the reconstruction era, the Seminoles were each given a seat in the two chambers of the Florida Parliament, but the Seminoles did not exercise this right. In the constitution of 1885 it was abolished by the Southern Democrats, along with the right to vote for blacks and other minorities.

Film adaptations

- In 1953, the film Seminola was shot in Hollywood , which tells how the cavalry lieutenant Caldwell (Rock Hudson) and his childhood friend Osceola (Anthony Quinn) try in vain to prevent a war over the intended relocation of the Seminoles. The superior Caldwells could not be dissuaded from raiding an Indian camp in the swamp forests of Florida and was defeated by the Seminoles. Caldwell faces a court martial and is sentenced to death.

- In 1971 DEFA shot the film Osceola - The Right Hand of Retribution (original title Osceola) which depicts the beginning of the Second Seminole War and the circumstances that led to it as true to history as possible. The desperate attempt to live peacefully with the white Americans, the relationship or coexistence of Indians and blacks, as well as the life of Osceola are reproduced based on historical traditions.

literature

- Thom Hatch: Osceola and the Great Seminole War: A Struggle for Justice and Freedom. St. Martin's Press, New York 2012. ISBN 978-0-312-35591-3 (print); ISBN 978-1-4668-0454-8 . (eBook)

See also

- Indian Wars

- Timeline of the Indian Wars

- Seminoles

- Black Seminoles

- Florida , History Section

swell

- Buker, George E. 1975. Swamp Sailors: Riverine Warfare in the Everglades 1835-1842 . Gainesville, Florida: The University Presses of Florida.

- Collier, Ellen C. 1993. Instances of Use of United States Forces Abroad, 1798-1993 . on Naval Historical Center - accessed March 11, 2010.

- Covington, James W. 1993. The Seminoles of Florida . University Press of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, ISBN 0-8130-1196-5 .

- Florida Board of State Institutions .: Soldiers of Florida in the Seminole Indian, Civil and Spanish-American wars . , 1903

- Giddings, Joshua Reed, The exiles of Florida: or, the crimes committed by our government against the Maroons, who fled from South Carolina and other slave states, seeking protection under Spanish laws , Columbus, Ohio, 1858.

- Higgs, Robert. 2005. “Not Merely Perfidious but Ungrateful”: The US Takeover of West Florida . at The Independent Institute - accessed March 11, 2010.

- Hitchcock, Ethan Allen . (1930) Edited by Grant Foreman. A Traveler in Indian Territory: The Journal of Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Late Major-General in the United States Army . Cedar Rapids, Iowa : Torch.

- Kimball, Chris. 2003. The Withlacoochee . ( Memento of March 22, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- Knead, Joe. 2003. Florida's Seminole Wars: 1817-1858 . Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-2424-7 .

- Mahon, John K. 1967. History of the Second Seminole War . Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press.

- Milanich, Jerald T. 1995. Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe . Gainesville, Florida : The University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1360-7 .

- Missall, John and Mary Lou Missall. 2004. The Seminole Wars: America's Longest Indian Conflict . University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2715-2 .

- Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army. 2001. Chapter 7: The Thirty Years' Peace . American Military History . P. 153, accessed March 11, 2010.

- Tebeau, Charlton W. 1971. A history of Florida , Coral Gables, Fla., University of Miami Press. ISBN 0-87024-149-4 .

- US Army National Infantry Museum. It was Indian . at US Army Infantry Home Page - URL retrieved October 22 , 2006 .

- Many, John. 1996. The Florida Keys: A History of the Pioneers . Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. ISBN 1-56164-101-4 .

- Vocelle, James T. 1914. History of Camden County Georgia , Camden Printing Company.

- Vone Research, Inc. The Seminole War Period. Coastal History . ( Memento of September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) - URL retrieved October 22 , 2006.

- Weisman, Brent Richards. 1999. Unconquered People . Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1662-2 .

- "American Military Strategy In The Second Seminole War," by Major John C. White, Jr.

- Letter Concerning the Outbreak of Hostilities in the Third Seminole War, 1856 , State Library and Archives of Florida, accessed March 11, 2010.

Web links

- Black Seminoles and the Second Seminole War: 1832–1838 , accessed March 11, 2010.

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. Milanich

- ↑ The Alachua Seminoles, however, retained their special identity at least until the end of the Third Seminole War.

- ↑ The English expression maroon for a runaway black slave is probably also derived from the Spanish word cimarrón .

- ↑ Missall, pp. 4–7, 128, Knetsch, p. 13, Buker, p. 9/10.

- ^ The Exiles of Florida , p. 79.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 10/12.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 12/13, 18.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 13, 15-18.

- ↑ Collier

- ↑ Collier

- ↑ Missall, pp. 16-20.

- ↑ Higgs

- ↑ Missall, pp. 21/22.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 24-27.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 27/28.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 28-32; Vocelle, p. 75.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 33-37.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 36/37; Knetsch, pp. 26/27.

- ↑ Missall, p. 38.

- ^ Office of the Chief of Military History.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 39/40.

- ↑ Missall, p. 42.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 42/43.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 46/47.

- ↑ Acquisition of Florida: Treaty of Adams-Onis (1819) and Transcontinental Treaty (1821) [1]

- ↑ Missall, p. 45.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 44, 47-50.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 53-61.

- ↑ Missall, p. 55.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 58-62.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 63-54.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 64/65.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 69-71.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 75/76.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 78-89.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 83-85.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 86/90.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 90/91.

- ↑ tebau, S. 158th

- ↑ Missall, pp. 91/92.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 94-121.

- ↑ Hitchcock, pp. 120-131.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 12-125.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 126-134, 140/141.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 138/139, 140/141; Mahon, p. 228.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 144–147, 151.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 152, 157-164.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 165-168.

- ↑ Missall, pp. 169-181, 182-184; Covington, pp. 98/99.

- ↑ Buker, pp. 99-101; Mahon, p. 289.

- ↑ Buker, pp. 106/107; Many, pp. 33-35; Mahon, pp. 283-284.

- ^ Mahon, p. 282.

- ↑ Knetsch, pp. 128-131; Mahon, p. 298.

- ↑ Mahon, pp. 298-300; Covington, pp. 103-106.

- ^ Covington, p. 107.

- ↑ Mahon, pp. 313/314, 316-318.

- ^ Kohn, George Childs: Dictionary of Wars , 3rd ed., P. 486.

- ↑ Mahon, pp. 321, 323, 325; Missall, pp. 177, 204/205; Florida Board of State Institutions, p. 9.

- ^ Covington, pp. 110/111.

- ^ Covington, pp. 112-114.

- ^ Covington, pp. 114-116.

- ^ Covington, pp. 116-118.

- ^ Covington, pp. 118-121.

- ^ Covington, pp. 122/123.

- ^ Covington, pp. 123-126.

- ^ Covington, p. 126.

- ^ Covington, pp. 126/127.

- ↑ Covington, S. 128/129.

- ^ Covington, pp. 130-132.

- ^ Covington, pp. 130-132.

- ^ Covington, pp. 132-133.

- ^ Covington, pp. 133/134.

- ^ Covington, pp. 134/135.

- ^ Covington, pp. 135/136.

- ^ Covington, pp. 135-140.

- ^ Covington, pp. 140-143.

- ^ Covington, pp. 145/146.