Ectopic pregnancy

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| O00.– | Ectopic pregnancy |

| O00.0 | Abdominal pregnancy |

| O00.1 | Tubal pregnancy |

| O00.2 | Ovarian pregnancy |

| O00.8 | Other ectopic pregnancy |

| O00.9 | Ectopic pregnancy, unspecified |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

As ectopic pregnancy ( EUG ) or ectopic pregnancy , including ectopic pregnancy or ectopic pregnancy is called a pregnancy in which the fertilized egg outside the uterine cavity (uterine cavity) ensconced has. Most extrauterine pregnancies occur in the fallopian tube and are therefore called ectopic pregnancies . However, implantation of the embryo can also occur in the ovaries and abdominal cavity . Pregnancies in the cervix , the uterine wall (for example in a scar after a caesarean section ) and in the intramural part of the fallopian tube are referred to as extrauterine pregnancy in the German translation of the ICD-10 , but are, strictly speaking, intrauterine but ectopic pregnancies.

With the exception of ectopic pregnancy , the embryo is not viable at an ectopic pregnancy. As a rule, the embryo dies after a few weeks due to an insufficient supply of nutrients, as the implantation site does not offer optimal conditions. In addition, ectopic pregnancy, including ectopic pregnancy, is a dangerous situation for the mother, as it can lead to severe, life-threatening internal bleeding, for example due to rupture of the fallopian tube.

Thanks to the improved diagnostic possibilities, extrauterine pregnancies can now be recognized very early. However, especially in countries with poor pregnancy care, extrauterine pregnancies are a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality despite improved diagnostics .

The treatment of an ectopic pregnancy usually consists of the surgical removal of the pregnancy, today usually via a laparoscopy . Alternatively, drug treatment may be effective in some cases.

Epidemiology

Ectopic pregnancies occur at a frequency of 1 to 2 in 100 intrauterine pregnancies. In most cases it is a tubular pregnancy, which is located in 4/5 of the cases in the ampullary part of the fallopian tube. 4 to 9% of pregnancy-related mortality in developed countries is due to extrauterine pregnancies. The fertility rate after ectopic pregnancy averages about 55%. However, there is a risk of recurrence of around 15%.

| Age (years) | Incidence Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| <20 | 0.4 |

| 20-30 | 0.7 |

| 30-40 | 1.3-2.0 |

In the last few years, in parallel with an increase in sexually transmitted infections, an increase in ectopic pregnancy has been recorded. In the United States , the number of new cases increased from 17,800 in 1970 ( incidence rate 4.5 per 1,000 pregnancies) to 88,400 in 1989 (16.0 per 1,000 pregnancies). Even after that, there was a further increase. However, mortality from this disease has decreased. However, it is the most common cause of death in the first three months of pregnancy and the fourth most common cause of mortality in the entire pregnancy.

Another reason for the increased incidence is the increased use of in vitro fertilization in women over 30 years of age. However, it can also be caused by improved early detection and the more frequent intrauterine contraception (contraception) using an IUD .

Emergence

In a normal pregnancy, the embryo reaches the uterine cavity at the blastocyst stage between the 5th and 6th day after fertilization and begins there on the 6th / 7th. Day to implant in the lining of the uterus . This process is called nidation or implantation.

During the first few days, the embryo is therefore completely dependent on the surrounding environment. If there is a disruption in the process of transport into the uterine cavity or implantation, this can result in an extrauterine implantation. In a typical ectopic pregnancy, the embryo attaches to the fallopian tube mucosa and grows into the mucous membrane. About 1% of the embryos settle outside the uterine cavity.

causes

There are a number of known risk factors for ectopic pregnancy. However, no such factors can be detected in a third to a half of the cases.

Risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease (pelvic inflammatory disease), infertility , the use of intrauterine devices , previous exposure to diethylstilbestrol , previous operations on the fallopian tube (tube surgery), intrauterine operations (scraping), smoking , previous ectopic pregnancies and a Sterilization . Although previous publications suggested a connection between endometriosis and ectopic pregnancies, this could not be proven.

Fallopian tube damage

The cilia of the fallopian tube mucous membrane transport the fertilized egg cell, which develops into an embryo through division, to the uterus. The number of cilia was sometimes reduced in ectopic pregnancies, leading to the hypothesis of ciliary damage, which is responsible for ectopic pregnancies. A 2010 review supported the hypothesis that ectopic pregnancies are caused by impaired embryo-tubal transport and changes in the fallopian tube environment leading to early implantation.

Women with inflammatory changes in the pelvis (pelvic inflammatory disease) are more likely to have ectopic pregnancies. This results from the formation of scar tissue in the fallopian tubes, which destroys the cilia. If both fallopian tubes are completely closed, the sperm and egg cell are unable to meet, so that fertilization of the egg cell is not possible, and therefore pregnancy does not occur. Surgical measures on the blocked fallopian tubes aim to reopen them. However, this removes the natural protection and increases the risk of an ectopic pregnancy. Intrauterine adhesions such as in Asherman's syndrome can on the one hand cause a cervical pregnancy. If these adhesions partially prevent access to the fallopian tube, it can also lead to an ectopic pregnancy. Asherman syndrome can be caused by intrauterine procedures such as curettage . A urogenital tuberculosis may be cause of Asherman's syndrome. In addition, there are adhesions of the fallopian tubes, which can also lead to extrauterine pregnancy.

A sterilization can increase an ectopic pregnancy the risk. 70% of all pregnancies after obliteration of the fallopian tubes are ectopic pregnancies, while 70% of pregnancies after fallopian tubes have been blocked by a clip are intrauterine. A Refertilization after sterilization also carries the risk of ectopic pregnancy. This is higher when more destructive methods, such as coagulation or partial removal of the fallopian tubes, have been chosen than with less destructive methods, such as clipping. A previous ectopic pregnancy increases the risk of a new ectopic pregnancy to 10%. This risk is also not reduced if the affected fallopian tube was removed and the other one appeared normal.

Other causes

Tobacco smoking is associated with a higher risk of ectopic pregnancy. Likewise, women who were exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) intrauterine are up to three times more likely than women without this exposure.

It has also been suggested that an abnormally increased formation of nitric oxide , through increased i-nitric oxide synthase activity (iNOS), reduces the number of strokes of the cilia and the contraction of the smooth muscle cells, thereby impairing embryo transport and thus leading to an ectopic pregnancy.

Although some research has shown a higher risk with age, it is believed that age is more of a surrogate marker for other risk factors.

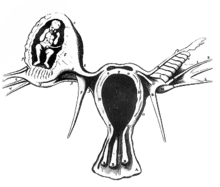

classification

N normal implantation ( nidation )

a ectopic pregnancy

b interstitial or cornuale ectopic pregnancy

c isthmic ectopic pregnancy

d ampullary ectopic pregnancy

e infundibular ectopic pregnancy

f Ovarschwangerschaft

g Zervixschwangerschaft

h intramural pregnancy

The majority of extrauterine pregnancies are found in one of the two fallopian tubes and are then called tubal or ectopic pregnancy. However, ectopic pregnancies also occur in the ovary, cervix, uterine wall, or in the abdominal cavity. Other rare locations are pregnancies in the ligamentum latum , the vagina , and in a rudimentary uterine horn in congenital malformations of the uterus. In individual cases, pregnancies also occurred after the uterus was removed ( hysterectomy ). If the fertilization of two egg cells leads to a simultaneous intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy, this is called a heterotopic pregnancy.

Tubal pregnancy

About 96% of all extrauterine pregnancies are ectopic pregnancies. Pregnancy occurs in the fallopian tube either near the fimbrial funnel (infundibular) (5% of all EUG), in the ampullary part (80%), in the isthmus (12%) and in the cornual or interstitial part of the fallopian tube (2%). The mortality in an isthmic or interstitial ectopic pregnancy is higher, as there is more frequent internal bleeding with a stronger blood supply (vascularization), such as from the ramus uterinus of the arteria ovarica , a connection to the arteria uterina , also known as Sampson's artery in the Anglo-American language , comes.

Ovarian pregnancy

About 0.2–2% of all extrauterine pregnancies are found in one ovary. An ovarian pregnancy can be distinguished from an ectopic pregnancy by the Spiegelberg criteria, named after the German gynecologist Otto Spiegelberg (1830–1881). After that, there is an ovarian pregnancy, if

- the sac is located in the ovary

- ectopic pregnancy is drawn to the uterus by the lig. ovarii proprium

- Ovarian tissue in the wall of the fruit sac can be demonstrated histologically

- the fallopian tube on the affected side is intact.

The clinical symptoms and the diagnostic findings correspond to those of tubal pregnancy. In the 1990s, an increase in ovarian pregnancy was observed, which was associated with gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT), an assisted reproductive process in which egg cells and sperm are brought into the fallopian tube together.

Cervical pregnancy

With 0.2–0.5% of ectopic pregnancies, cervical pregnancy is very rare. Due to the close anatomical relationship, there is usually early contact with the flow area of the arteria uterina , so that a curettage can lead to massive, insatiable bleeding, which can make a hysterectomy necessary. With the transvaginal ultrasound examination, cervical pregnancies can usually be recognized early. The diagnostic criteria are:

- empty womb (uterus)

- barrel-shaped cervix (cervix uteri)

- Gestational sac below the level of the orificium internum uteri

- "Sliding Sign": When pressure is exerted on the uterus with the transducer , the gestational sac can be moved to the cervical canal during extrauterine cervical pregnancy. During a regular pregnancy due to the adhesions, the gestation sac cannot be moved to the cervical canal.

- Blood flow around the gestation sac in the color Doppler

Intramural pregnancy

Intramural pregnancy is a pregnancy that is implanted in the uterine muscles ( myometrium ) and not surrounded by decidua . Risk factors are adenomyosis uteri and previous operations on the uterus, such as a caesarean section, which can lead to an implantation in the scar. Intramural pregnancies are very rare, accounting for <1% of all extrauterine pregnancies.

Ectopic pregnancy

About 1% of extrauterine pregnancies are localized in the abdominal cavity. Because of the often low symptoms, abdominal pregnancies are sometimes recognized late. In advanced pregnancies, the placenta sits on the abdominal organs or the peritoneum and has a sufficient supply of blood. This is usually the case in the intestines and mesentery. Other locations, such as those near the renal artery, hepatic artery or the aorta have also been reported.

Although live births are very rare in ectopic pregnancies , they are extremely dangerous because of the high risk of bleeding. Most ectopic pregnancies therefore have to be removed by laparotomy after the diagnosis is made well before the fetus is able to survive .

The maternal morbidity and the mortality of mother and child are high (mother 20%, child 80%), since removal of the placenta usually leads to uncontrollable bleeding. For this reason, for example, intestinal segments are removed together with the placenta.

Depending on the location of the placenta, consideration must also be given to leaving the placenta where it will calcify or reabsorb over time .

Tubal abortion

During nidation, blood vessels open and bleed. The fallopian tube can fill with blood and is then known as the hematosalpinx . If there is an implantation near the fimbrial funnel, bleeding from the fimbrial end occurs after the fruit capsule has broken open. The blood can push the pregnancy out of the fallopian tube. However, this so-called tubal abortion is rare.

Heterotopic pregnancy

In rare cases, fertilization of two egg cells results in simultaneous intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy. This is called heterotopic pregnancy. Due to the symptoms that arise, the intrauterine pregnancy is often only discovered after the ectopic. Since an ectopic pregnancy is surgically removed at an early stage, the intrauterine pregnancy is often not yet visible on ultrasound. If the hCG levels rise after the operation, there is a possibility of a normal pregnancy still developing.

Although heterotopic pregnancies are very rare, their frequency is increasing. This is attributed to the increasing use of IVF. The intrauterine embryo survival rate is about 70%.

Successful pregnancies after rupture of the fallopian tube have also been reported when the placenta settles on abdominal organs or the outer wall of the uterus.

Persistent ectopic pregnancy

Persistent extrauterine pregnancy is when trophoblasts persist after organ-preserving removal of the ectopic pregnancy. In 15 to 20% of women, trophoblast tissue grows again after such an operation, some of which is embedded in deeper fallopian tube layers. It forms new hCG and can lead to renewed clinical symptoms such as bleeding after weeks. Therefore, after ectopic pregnancies, the serum hCG values are checked in order to observe their decrease. It is also possible to administer methotrexate at the same time as the operation .

Pregnancy after hysterectomy

In a few isolated cases, extrauterine pregnancies after hysterectomy have been reported. Most of these were early ectopic pregnancies that had already existed at the time the uterus was removed and had not been recognized. But even several years after the hysterectomy, pregnancies occurred that must have arisen from fistulas between the vagina and the abdominal cavity. Even after the cervix was preserved, there have been isolated reports of later extrauterine pregnancies.

Symptoms

Early symptoms in ectopic pregnancy can be very mild or completely absent. Clinically, there is an ectopic pregnancy between the 5th and 8th week after the start of the last menstrual bleeding (on average after 7.2 weeks). If modern diagnostic options are not available, it is more often the case that an extrauterine pregnancy is discovered later.

Possible symptoms of ectopic pregnancy can include:

- Breast tenderness

- frequent urination and dysuria

- Missing period ( secondary amenorrhea )

- Nausea , vomiting

- Pelvic pain (usually on the side of an ectopic pregnancy)

- vaginal bleeding, usually of low intensity, which makes it difficult to distinguish between a disturbed early pregnancy, nidation bleeding or a normal pregnancy

As the disease progresses, the pain usually increases due to internal bleeding and vaginal bleeding due to falling progesterone levels. Inflammation does not play a role in the development of pain in an ectopic pregnancy . Since inflammation in the pelvic area occurs extremely rarely during pregnancy, adnexitis can almost be ruled out if the pregnancy test is positive . Ectopic pregnancy can also cause symptoms such as those found in appendicitis , diseases of the urinary tract or the gastrointestinal tract. The pain is caused by prostaglandins that are released at the implantation site or by free blood in the abdominal cavity, which irritates the peritoneum .

Diagnosis

An ectopic pregnancy must be assumed in every woman with abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding if the pregnancy test is positive. An ultrasound examination , which shows a fruit sac with fetal parts and heart actions outside the uterus, is evidence of an extrauterine pregnancy.

An insufficient increase in the β-hCG in the serum can also be an indication of an ectopic pregnancy. From a β-hCG value of around 1500 IU / ml, a normal intrauterine pregnancy can be shown with high probability on ultrasound. If a high-resolution transvaginal sonography does not show an intrauterine pregnancy at such a value, an extrauterine pregnancy must be considered.

In recent years, the use of progesterone determination has become more and more important, especially in the case of low β-HCG values, where ultrasound diagnostics have not yet provided any information. For example, a high progesterone level combined with a low level of β-HCG suggests an early, but probably intact, intrauterine pregnancy. However, if this progesterone level is low, the pregnancy is disturbed and an ectopic pregnancy is more likely.

An ectopic pregnancy can be visualized using a laparoscopy or laparotomy . After tubal abortion or rupture, it can be difficult to find the pregnancy tissue. A laparoscopy in an early week of pregnancy can provide normal findings despite an ectopic pregnancy.

A puncture of the Douglas space (Kuldozentese) was previously used to detect intra-abdominal bleeding before the introduction of ultrasound into clinical routine. Today it no longer plays a role in the diagnosis of extrauterine pregnancy. The Cullen's sign may also indicate a ruptured ectopic pregnancy with bleeding into the abdominal cavity.

treatment

Surgical therapy

Surgical treatment is necessary if bleeding has occurred or cardiac action is detected. The pregnancy can then be removed by means of a laparoscopy or an abdominal incision. In the case of an ectopic pregnancy, an opening of the fallopian tube (salpingotomy) with preservation of the fallopian tube is often necessary. Alternatively, the fallopian tube can be completely removed (salpingectomy).

Medical therapy

Since 1993, early ectopic pregnancy can also be treated with systemic or local administration of methotrexate . The drug, a cytostatic agent, inhibits the growth of the embryo and causes an abortion, which is then reabsorbed in the abdominal cavity or expelled vaginally. Contraindications are liver, kidney or blood diseases as well as an ectopic pregnancy of> 3.5 cm.

Possible complications

The most common complication of ectopic pregnancy is internal bleeding, leading to hypovolemic shock . However, mortality is low when there is access to modern medical care.

Schematic representation of a tubal rupture

forecast

Post-ectopic fertility depends on several factors. The most important factor here is an unfulfilled desire to have children in the past. The choice of treatment also plays a role. The rate of subsequent intrauterine pregnancies is higher after methotrexate treatment than after surgical therapy. The chances of conceiving are better after receiving the fallopian tube than after removing it.

Live births in ectopic pregnancies

Live births have been repeatedly reported in ectopic pregnancies born through an abdominal incision (laparotomy).

- In 1986 an abdominal incision was made in Germany on suspicion of a uterine rupture and an ectopic pregnancy was developed on the date.

- In 1999, a healthy girl was born in Ogden, Utah , USA , who had developed outside of the uterus, which was not detected by obstetric ultrasound. The location of the pregnancy was only determined after a caesarean section.

- Also in 1999, a 32-year-old British woman gave birth to triplets. Two children developed in the uterus and the third after the fallopian tube ruptured in the abdominal cavity.

- In 2008, a 37-year-old British woman was diagnosed with a greater omentum . The child was born in the 28th week of pregnancy. Mother and child survived.

- In 2008, an ovarian pregnancy was found in a 34-year-old Australian woman who was 38 weeks pregnant. The girl weighed 2,800 g and was healthy.

- In 2011, a 23-year-old woman was given birth to a healthy child in Saudi Arabia. An ectopic pregnancy was found during a caesarean section because of breech position . During the ultrasound examinations during pregnancy, the suspicion of a bicornuate uterus , a malformation of the uterus , was expressed. In addition, the woman had reported complaints in the lower abdomen during pregnancy.

In 2008, however, 163 cases of advanced ectopic pregnancies since 1946 were analyzed in a publication. The incidence was 19% higher in non-industrialized countries. In only 45% of the cases described, the diagnosis was correctly made before the operation. 72% of the fetuses and 12% of the mothers died.

Veterinary medicine

Ectopic pregnancy also occurs in other mammals , especially all domestic animals. Ectopic pregnancies are most common in cattle .

While primarily primary ectopic pregnancies occur in humans and the pregnancy has immediately lodged itself in the wrong place, in animals it is mostly secondary ectopic pregnancies. An embryo or fetus comes out of the uterus and nests in another place, usually in the free abdominal cavity.

Ovarian pregnancy has not yet been described in the animal kingdom. Ectopic pregnancies are also of no importance in veterinary medicine.

history

The first description of an extrauterine pregnancy in 963 is attributed to Albucasis (936-1013). He reported on a patient with a swelling of the abdomen, from which pus flowed over the abdominal wall, in which a human skeleton was found. Jacob Noierus carried out the first surgical interventions in ectopic pregnancy in 1591 and 1596, in which he merely pulled the fetus out through an abdominal incision. The Frenchman Jean Riolan (1577–1657) from Paris first reported in 1604 about a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. The patient died in the fourth month of her eighth pregnancy one day after the symptoms began.

In 1672 Reinier de Graaf published De mulierum organis in generationi inservientibus tractatus novus in his work . a pictorial representation based on a work by the French surgeon Benoit Vassal on autopsy findings in a 32-year-old woman who had already given birth to eleven children and died on January 6, 1669 of a hemorrhage during an ectopic pregnancy. In 1693, Bussière from Paris found an unruptured ectopic pregnancy during the autopsy of an executed young woman. The French doctor de Saint Maurice from the Périgord described the first ovarian pregnancy in 1682. In this woman, too, the diagnosis was only made after death.

The American John Bard (1716–1799), father of obstetrician Samuel Bard (1742–1821), carried out the first successful operation for an EUG through an abdominal incision in 1759 in New York . He removed a dead but mature fetus from a 28-year-old woman who survived the procedure.

William Baynham (1749-1814) reported two cases of EUG, which he treated surgically. One had already occurred 5 years earlier.

The removal of an ectopic pregnancy through the vagina in 1816 by John King from South Carolina was also successful .

Up until the end of the 19th century, the diagnosis was made by palpating a tumor to the side or behind the enlarged uterus, uncertain signs of pregnancy such as stomach and chest discomfort, missed menstruation , increased blood flow to the vagina and rocking back and forth (balloting). of the tumor content. Since the ectopic fetus was considered to be the cause of mortality, the primary goal of treatment was to kill it. This was attempted through starvation, enemas and bloodletting in the mother, as well as the use of strychnine , electrotherapy , galvanotherapy and injection of morphine into the sac . However, the prognosis was poor. The death rate was 72 to 99%. Ectopic pregnancy was one of the leading causes of death in young women at the time. This only improved with the introduction of the removal of the fallopian tubes (salpingectomy) by Robert Lawson Tait (1845–1899), who first performed it in 1884.

The German gynecologist Richard Frommel (1854–1912) was one of the first to advocate immediate surgical intervention in extrauterine pregnancy, contrary to the then prevailing doctrine that recommended wait-and-see behavior.

While the mortality was 12.3% between 1908 and 1920, it fell to 11.7% between 1920 and 1937 and was only 1.7 to 2.7% between 1937 and 1947. This was the result of the introduction of blood transfusions as a routine procedure, a better understanding of the shock mechanisms, improved care after operations and earlier diagnosis through increased use of kuldozentesis and pregnancy tests .

Kuldoscopy was used as a further diagnostic procedure in the early 1960s . However, the idea of looking directly at the abdominal cavity arose around the beginning of the 20th century. As early as 1901, the Russian doctor DO Ott was able to depict pelvic and abdominal organs by opening the Douglas room (kuldotomy), vaginal mirrors and a head mirror, which he called ventroscopy.

The Swede Hans Christian Jacobaeus (1879–1937) was the first to describe the technique of laparoscopy in 1910 and used it primarily for diagnosing patients with ascites and liver diseases. In 1929 the internist Hans Kalk (1895–1973) developed a new type of laparoscope. It enabled an exact diagnosis and Kalk already recognized that “a large area of indications would open up for laparoscopy in gynecology”, which was confirmed after the introduction by Hans Frangenheim .

In 1953, WB Stromme broke the practice of removing the fallopian tube by opening the fallopian tube to remove the product of pregnancy and thereby preserving it. Twenty years later, HI Shapiro and DH Adler succeeded in laparoscopic removal of an ectopic pregnancy in 1973.

Diagnosis, which is increasingly earlier today, has become possible thanks to significantly improved pregnancy tests, the quantitative determination of β-hCG and vaginal ultrasound examinations .

literature

- Jürgen Hucke: Ectopic pregnancy. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8047-1480-3 .

- W. Pschyrembel , JW Dudenhausen: Practical obstetrics. 17th edition. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-11-012881-0 , p. 565 ff.

- Peter Oppelt: Ectopic pregnancy. In: Manfred Kaufmann , Serban-Dan Costa , Anton Scharl: Die Gynäkologie. 2nd Edition. Springer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-540-25664-4 , pp. 286-301.

- E. Kucera, R. Lehner, Peter Husslein : Extrauterine pregnancy. In: Henning Schneider , Peter Husslein, Karl Theo M. Schneider: The obstetrics. 3. Edition. Springer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-540-33896-9 , pp. 32-39.

- Heinrich Schmidt-Matthiesen, Diethelm Wallwiener: Gynecology and obstetrics. Schattauer Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7945-2618-5 , p. 179.

Web links

- Ectopic pregnancy. Information from the Gynecological Endoscopy Working Group V. of the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics

- Entry on extrauterine pregnancy in the Flexikon , a Wiki of the DocCheck company

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d E. Kucera, R. Lehner, Peter Husslein: Extrauterine pregnancy. In: Henning Schneider, Peter Husslein, Karl Theo M. Schneider: The obstetrics. 3. Edition. Springer Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-540-33896-9 , pp. 32-39.

- ↑ a b WHO: Maternal and perinatal health. last accessed on November 9, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Jürgen Hucke, Ulrich fillers: Extrauterine pregnancy. In: Gynecologist. 38 (2005), pp. 535-552, doi: 10.1007 / s00129-005-1705-1

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j J. Lermann, A. Müller, C. Schulze, S. Becker, A. Boosz, SP Renner, MW Beckmann: Die Extrauteringravidität. In: Gynecology. up2date 3 (2009), pp. 383-402, doi: 10.1055 / s-0029-1224626

- ↑ Surveillance for Ectopic Pregnancy - United States, 1970-1989. In: MMWR. 42 (1993) (SS-6), pp. 73-85, wonder.cdc.gov

- ↑ B. Trabert, VL Holt, O. Yu, SK Van Den Eeden, D. Scholes: Population-based ectopic pregnancy trends, 1993-2007. In: Am J Prev Med. 40 (2011), pp. 556-560, PMID 21496755

- ↑ AA Creanga, CK Shapiro-Mendoza, CL Bish, S. Zane, CJ Berg, WM Callaghan: Trends in ectopic pregnancy mortality in the United States: 1980-2007. In: Obstet Gynecol. 117 (2011), pp. 837-843, PMID 21422853 .

- ↑ T. Sadler: Medical Embryology. 10th edition. Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-13-446610-4 , pp. 25-44.

- ↑ CM Farquhar: Ectopic Pregnancy. In: Lancet. 366 (2005), p. 583, PMID 16099295

- ↑ AK Majhi, N. Roy, KS Karmakar, PKJ Banerjee: Ectopic pregnancy - on analysis of 180 cases. In: Indian Med Assoc. 105 (2007), pp. 308, 310, 312 passim , PMID 18232175 .

- ↑ BestBets: Risk Factors for Ectopic Pregnancy. Retrieved December 2, 2011 .

- ↑ G. Bogdanskiene, P. Berlingieri, JG Grudzinskas: Association between ectopic pregnancy and pelvic endometriosis. In: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 92 (2006), pp. 157-158, doi: 10.1016 / j.ijgo.2005.10.024

- ↑ RA Lyons, E. Saridogan, O. Djahanbakhch: The reproductive significance of human Fallopian tube cilia . In: Hum Reprod Update . tape 12 , no. 4 , 2006, p. 363-372 , doi : 10.1093 / humupd / dml012 , PMID 16565155 .

- ↑ JL Shaw, SK Dey, HO Critchley, AW Horne: Current knowledge of the aetiology of human tubal ectopic pregnancy. Hum Reprod Update 16 (2010), pp. 432-444, PMID 20071358 , doi: 10.1093 / humupd / dmp057 .

- ↑ JI Tay, J. Moore, JJ Walker: Ectopic pregnancy . In: West J Med. Band 173 , no. 2 , 2000, pp. 131-134 , doi : 10.1136 / ewjm.173.2.131 , PMID 10924442 , PMC 1071024 (free full text).

- ↑ a b c d e L. Speroff, RH Glass, NG Kase: Clinical Gynecological Endocrinology and Infertility. 6th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999, ISBN 0-683-30379-1 , pp. 1149 ff.

- ↑ a b J. G. Schenker, EJ Margalioth: Intra-uterine adhesions: an updated appraisal . In: Fertility and Sterility . tape 37 , no. 5 , 1982, pp. 593-610 ., PMID 6281085 .

- ↑ C. Klyszejko, J. Bogucki, D. Klyszejko, W. Ilnicki, S. Donotek, J. Kozma: Cervical pregnancy in Asherman's syndrome [article in Polish]. In: Ginekol Pol . tape 58 , no. 1 , 1987, pp. 46-48 , PMID 3583040 .

- ↑ D. Dicker, D. Feldberg, N. Samuel, JA Goldman: Etiology of cervical pregnancy. Association with abortion, pelvic pathology, IUDs and Asherman's syndrome. In: J Reprod Med . tape 30 , no. 1 , 1985, pp. 25-27 , PMID 4038744 .

- ↑ O. Bukulmez, H. Yarali, T. Gurgan: Total corporal synechiae due to tuberculosis carry a very poor prognosis following hysteroscopic synechialysis . In: Human Reproduction . tape 14 , no. 8 , 1999, p. 1960–1961 , doi : 10.1093 / humrep / August 14 , 1960 , PMID 10438408 .

- ↑ M. Al-Azemi, B. Refaat, S. Amer, B. Ola, N. Chapman, W. Ledger: The expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in the human fallopian tube during the menstrual cycle and in ectopic pregnancy . In: Fertil. Sterile. tape 94 , no. 3 , May 2009, p. 833-840 , doi : 10.1016 / j.fertnstert.2009.04.020 , PMID 19482272 .

- ↑ F. Plotti, A. Di Giovanni, C. Oliva, F. Battaglia, G. Plotti: Bilateral ovarian pregnancy after intrauterine insemination and controlled ovarian stimulation. In: Fertil Steril. 90 (2008), p. 2015, pp. E3 – e5, PMID 18394622 , doi: 10.1016 / j.fertnstert.2008.02.117

- ^ Spiegelberg criteria on whonamedit.com

- ↑ F. Lehmann, N. Baban, B. Harms, U. Gethmann, R. Krech: Ovarian pregnancy after gamete transfer (GIFT) a case report. In: obstetric women's health. 51 (1991), pp. 945-947, doi: 10.1055 / s-2008-1026242

- ↑ Diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy with ultrasound . In: Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology (= Acute Gynaecology Volume 1: Early Pregnancy Complications ). tape 23 , no. 4 , August 2009, p. 501-508 , doi : 10.1016 / j.bpobgyn.2008.12.010 .

- ↑ HK Atrash, A. Friede, CJ Hogue: Abdominal pregnancy in the United States: frequency and maternal mortality. Obstet Gynecol 69: 333-337 (1987).

- ↑ I. Delke, NP Veridiano, ML Tancer: Abdominal pregnancy: review of current management and addition of 10 cases. In: Obstet Gynecol. 60: 200-204 (1982).

- ^ 'Special' baby grew outside womb. BBC news, August 30, 2005, accessed July 14, 2006 .

- ↑ Bowel baby born safely. BBC news, March 9, 2005, accessed November 10, 2006 .

- ^ J. Zhang, F. Li, Q. Sheng: Full-term abdominal pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature . In: Gynecol. Fruit. Invest. tape 65 , no. 2 , 2008, p. 139-141 , doi : 10.1159 / 000110015 , PMID 17957101 .

- ↑ K. Talbot, R. Simpson, N. Price, SR Jackson: Heterotopic pregnancy. In: J Obstet Gynaecol. 31 (2011), pp. 7-12, PMID 21280985

- ↑ Claude Henri Diesch: Heterotopic Pregnancy - A Current Review of the Literature. In: Speculum. 23 (2005), pp. 17-21, kup.at (PDF; 158 kB)

- ↑ E. Kemmann, S. Trout, A. Garcia: Can we predict patients at risk for persistent ectopic pregnancy after laparoscopic salpingotomy? In: The Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists . tape 1 , no. 2 , February 1994, p. 122-126 , doi : 10.1016 / S1074-3804 (05) 80774-1 , PMID 9050473 .

- ↑ G. Tews, T. Ebner, K. Jesacher: Features of the ectopic pregnancy. In: Journal of Reproductive Medicine and Endocrinology. No. 1 (4), 2004, pp. 268-271.

- ↑ eMedicine - Surgical Management of Ectopic Pregnancy: Article Excerpt by R Daniel Brown. Retrieved September 17, 2007 .

- ^ U. Mahboob, SB Mazhar: Management of ectopic pregnancy: a two-year study . In: Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad: JAMC . tape 18 , no. 4 , 2006, p. 34-37 , PMID 17591007 .

- ^ L. Clark, S. Raymond, J. Stanger, G. Jackel: Treatment of ectopic pregnancy with intraamniotic methotrexate - a case report . In: The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology . tape 29 , no. 1 , 1989, pp. 84-85 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1479-828X.1989.tb02888.x , PMID 2562613 .

- ↑ Togas Tulandi, Seang Lin Tan: Advances in Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Current Trends and Developments . Informa Healthcare, 2002, ISBN 0-8247-0844-X , p. 240 .

- ^ A b William W. Hurd, Tommaso Falcone: Clinical reproductive medicine and surgery . Mosby / Elsevier, St. Louis, Mon 2007, ISBN 978-0-323-03309-1 , pp. 724 .

- ↑ Michael Böhme, Jürgen Nieder, Wolfgang Weise : Ectopic pregnancy at the appointment with a living child. In: Zentralbl Gynakol. 108: 516-519 (1986) PMID 3727853

- ↑ Registry Reports. (PDF) (No longer available online.) In: Volume XVI, Number 5. ARDMS The Ultrasound Choice, Ogden, Utah, October 1999, archived from the original on December 23, 2010 ; accessed on June 22, 2011 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Miracle baby. (No longer available online.) Utah News from KSL-TV, Ogden, Utah, August 5, 1999, archived from the original on September 30, 2011 ; accessed on June 22, 2011 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Doctors hail 'miracle' baby. In: BBC News. September 10, 2009, accessed December 2, 2011 .

- ↑ Laura Collins: Miracle baby Billy grew outside his mother's womb. In: Daily Mail, London. August 31, 2008, accessed September 3, 2008 .

- ^ Baby Born After Rare Ovarian Pregnancy. Associated Press May 30, 2008, archived from the original June 3, 2008 ; Retrieved September 5, 2012 .

- ^ Rebekah Cavanagh: Miracle baby may be a world first. May 30, 2008, accessed May 30, 2008 .

- ↑ Amal A Dahab, Rahma Aburass, Wasima Shawkat, Reem Babgi, Ola Essa, Razaz H Mujallid: Full-term extrauterine abdominal pregnancy: a case report. In: J Med Case Reports. 5 (2011), p. 531, PMID 22040324 , jmedicalcasereports.com (PDF; 410 kB).

- ↑ D. Nkusu Nunyalulendho, EM Einterz: Advanced abdominal pregnancy: case report and review of 163 cases reported since 1946. In: Rural Remote Health. 8 (2008), p. 1087, rrh.org.au

- ↑ Johannes Richter: Animal Obstetrics. Georg Thieme Verlag, 1993, ISBN 3-489-53416-6 , p. 146.

- ↑ a b c d e f S. Lurie: The history of the diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy: a medical adventure. In: Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 43 (1992), pp. 1-7, PMID 1737602 , elsevierhealth.com (PDF)

- ^ Toby E. Huff: Intellectual Curiosity and the Scientific Revolution: A Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-17052-9 , p. 196.

- ↑ Ectopic Pregnancy ( Memento of 26 May 2011 at the Internet Archive )

- ↑ John Bard: A Case of Extra-Uterine Fetus. In: Medical Observations and Inquiries of the Society of Physicians of London. Vol. 2 (1764), pp. 369-372.

- ↑ Ira M. Rutkow: The History of Surgery in the United States, 1775-1900: Periodicals and pamphlets. Norman Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0-930405-48-X , p. 89.

- ^ John King: Analysis of the subject of extra-uterine foetation, and of the retroversion of the gravid uterus. Wright, Norwich 1818.

- ^ Marc A. Fritz, Leon Speroff: Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2010, ISBN 978-0-7817-7968-5 , p. 1384.

- ↑ JS Parry, HC Lea: Extrauterine pregnancy. In: Am J Obstet Gynecol. 9, pp. 169-170 (1976).

- ^ Robert Lawson Tait: Five cases of extrauterine pregnancy operated upon at the time of rupture. Br Med J 1 (1884), p. 1250.

- ^ Robert Lawson Tait: Pathology and Treatment of Extrauterine Pregnancy. In: Br Med J. 2 (1884), p. 317.

- ^ Robert Lawson Tait: Lectures on ectopic pregnancy. Birmingham 1888, pp. 23, 25.

- ↑ History of the Erlangen University Women's Clinic ( Memento of the original from December 6, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Richard Frommel : On the therapy and anatomy of tube pregnancy. In: Deutsch Arch Klin Med. 42 (1888), pp. 91-102.

- ↑ P. Graffagnino: Ectopic pregnancy. In: Am J Obstet Gynecol 4. (1922), pp. 148-158.

- ↑ CG Collins, WD Beacham, DW Beacham: Ectopic pregnancy, mortaiity and morbidity factors. In: Am J Obstet Gynecol. 57, pp. 1144-1154 (1949).

- ↑ HL Riva, LA Kammeraad, PS Anderson: Ectopic pregnancy: report of 132 cases and comments on the role of the culdoscope in diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol 20: 189-198 (1962).

- ↑ DO Ott: Ventroscopic illumination of the abdominal cavity in pregnancy. In: Z Akus i Zhensk Bolez. 15 (1901), p. 7.

- ^ Hans Christian Jacobaeus : About the possibility of using cystoscopy when examining serous cavities. Münch Med Wochenschr 57 (1910), pp. 2090-2092.

- ↑ Hans Christian Jacobaeus : Brief overview of my experiences with laparoscopy. Münch Med Wochenschr 58 (1911), p. 2017.

- ↑ Hans Kalk : Experience with laparoscopy (at the same time with a description of a new instrument). In: Z Klin Med. 111 (1929), p. 303.

- ↑ Hans Kalk , Egmont Wildhirt : Textbook and Atlas of Laparoscopy and Liver Puncture. Thieme, Stuttgart 1962.

- ↑ Hans Frangenheim : The importance of laparoscopy for gynecological diagnostics. In: Fortschr Med. 76 (1958), pp. 451-452.

- ↑ Hans Frangenheim : The laparoscopy and the culdoscopy in gynecology. Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 1959.

- ↑ WB Stromme: Salpingostomy for tubal pregnancy: Report of a successful case. Obstet Gynecol 1 (1953), pp. 472-475.

- ^ HI Shapiro, DH Adler: Excision of an ectopic pregnancy through the laparoscope. In: Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973, 117, pp. 290-291, PMID 4269637 .