Women's suffrage in Europe

The enforcement of women's suffrage in Europe went from the 18th century a long struggle of the women's movement ahead:

The women in the countries wanted and should be given the right to political polls actively as passively take part, so even choose how well elected to.

history

Olympe de Gouges is considered to be the first “modern” fighter for women's suffrage . In the course of the French Revolution , she wrote, among other things, the Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens (published September 1791), was arrested during the reign of terror in the summer of 1793 for hostility to Robespierre and executed in the autumn after a brief show trial.

In 1838, the British crown colony of Pitcairn , an island in the South Pacific, was the first territory to have sustainable women's suffrage.

In 1906, Finland was the first European country to give women the right to vote with its state legislature of June 1st. Finland was then a Russian Grand Duchy . The reasons why the Scandinavian countries were the first to introduce the right to vote for women are closely linked to the political trends and innovations of the time. Finland became the pioneer of women's suffrage in Europe after the Russian tsar, to whom the Finnish parliament was then subordinate, promised a reform of the suffrage. The women's rights movement in Finland and other Scandinavian countries was hot at the time. So it happened that the demands of Finnish women for voting rights were taken into account in the course of the reform. Finland was the first country where women not only theoretically had the right to stand for election, but were actually elected to parliament.

General women's suffrage was introduced in Norway in 1913 through new legislation and in Denmark in 1915 through an amendment to the Danish constitution . In 1917 the right to vote was introduced in the Netherlands (active followed in 1919).

After the February Revolution in 1917, women in Russia gained the right to vote and stand for election. They were admitted to the elections for the Soviets as well as for the City of Dumas . The following year, women's suffrage was enshrined in the RSFSR constitution of July 10, 1918.

On February 6, 1918, the United Kingdom followed suit with the Representation of the People Act 1918 , although the right to vote was initially restricted to women over 30 if they themselves or their spouses had property-based municipal voting rights. Full electoral equality was granted on July 2, 1928.

On November 28, 1918, universal suffrage for women was introduced by state decree in Poland , which had regained its independence after the First World War . The first eight women moved to the newly elected Sejm in 1919 . Even before 1795 and the partitions of Poland (1772, 1793 and 1795) women paying taxes had partial voting rights.

In Austria , women received universal suffrage on November 12, 1918 ( men 1907 ) through the law on the state and form of government of German Austria , with which it declared itself a republic in the course of the collapse of Austria-Hungary : Article 9 speaks for the upcoming Election of the constituent national assembly of “general, equal, direct and secret voting rights of all citizens regardless of gender” and Article 10 of “Suffrage and electoral procedures of state, district, district and municipal councils”.

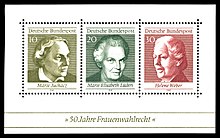

Marie Juchacz , Marie-Elisabeth Lüders and Helene Weber

Caricature by Gustav Brandt , front page of the Kladderadatsch magazine from January 19, 1919

On the same day, the Council of People's Representatives in Germany published an appeal to the German people in which the Reich government, which came to power in the course of the November Revolution, proclaimed "with the force of law": "All elections to public bodies are henceforth based on the same, secret, direct to exercise universal suffrage on the basis of the proportional electoral system for all male and female persons aged at least 20 years. ”Shortly afterwards, the right to vote was legally fixed with the ordinance on elections to the German constituent assembly of November 30, 1918. In this way, women in Germany were able to exercise their right to vote at national level for the first time in the election to the German National Assembly on January 19, 1919. Austria and Germany were thus among the avant-garde in Europe. In memory of the decision at that time in Germany that gave German Post AG with the initial issue date January 2, 2019 a special stamp in the nominal value of 70 euro cents with the inscription 100 years of women's suffrage out. The design comes from the graphic artist Frank Philippin from Höchst in the Odenwald .

The Czechoslovakia led in 1920 a women's suffrage, Sweden in 1921. In December 1931, Spain has the right to vote for women in the Constitution of the Second Spanish Republic recognized in 1931, and applied for the first time in the parliamentary elections of November 1933rd

On December 11, 1934, two months before a parliamentary election in Turkey , women in Turkey were given the right to vote and stand for election.

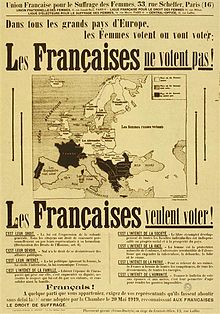

In July 1936, the French Chamber of Deputies voted unanimously (475 to 0) for women's suffrage; however, the text was not placed on the agenda of the second chamber (Senate). The draft constitution of January 20, 1944 contained women's suffrage: On April 21, 1944, the Comité français de la Liberation nationale spoke out in favor of women's suffrage. After the end of the German occupation of France on October 5, 1944, the Provisional Government of the French Republic agreed. They were entitled to vote for the first time in the municipal elections on April 29, 1945; the first election at national level was the election of the National Assembly on October 21, 1945 . 33 of the 586 elected MPs (= 5.6%) were women.

In 1946 the Italian women were given full suffrage (previously they had - since 1925 - only the right to vote at the municipal level), in 1948 the Belgian women .

On February 7, 1971, after a successful referendum , the women's suffrage in Switzerland on the federal level introduced. In 1959, the majority of men eligible to vote had rejected women's suffrage. At the cantonal level, it was first introduced in 1959 in the canton of Vaud ; The last canton to join was the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden in 1990 - albeit not voluntarily, but based on a decision by the Federal Supreme Court .

In 1984, Liechtenstein became the last Western European country to join, after the introduction had previously been rejected in two referendums (1971 and 1973).

First demands

In Europe, the first voices for the political participation of women were raised during the French Revolution when Olympe de Gouges published the Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens in 1791 . French women also demanded the right to vote during the revolutions of 1831 and 1848. In Great Britain , the first petition for women's suffrage was introduced in 1832. Hedwig Dohm demanded the right to vote in 1876 in her work “The women nature and law. On the women's question ”. In all countries, however, the votes that demanded women's suffrage (such as in 1869 publicly by the Saxon Louise Otto-Peters ) remained the exception; they hardly met with understanding or even with a response. In the last third of the 19th century, in a number of European countries, such as Sweden and Denmark, the voices for women's suffrage gradually grew louder. Contrary to what has long been claimed in research, German women did not go a separate way; they were neither particularly late in getting involved, nor were they particularly reticent. In 1891 the Social Democrats were the first party to demand women's suffrage. The German bourgeois women's movement, like in other countries at the end of the 19th century, campaigned for the right to vote, for example Helene Lange from the early 1890s and then in 1896 in her programmatic publication “Frauenwahlrecht”. It was not by chance that the International Woman Suffrage Alliance was founded in Berlin in 1904 .

In some Mediterranean countries, the first demands arose after 1900, sometimes only after the First World War . In Britain, the suffragette movement advocated women's suffrage and general women's rights in the early 20th century . A minority of the British suffragettes around Emmeline Pankhurst made use of violence, making them an exception among women campaigners around the world.

The triggers for the emergence of a women's suffrage movement were:

- Suffrage reforms that benefited only men and ignored women

- Electoral laws that deprived a minority of privileged women from the right to vote which they traditionally enjoyed, as in Great Britain and Austria, and

- the strengthening of women's movements, which not only strived for civil, but also political rights. In the Eastern European countries, which were ruled by Russia, Austria and Prussia, no independent women's movement could develop. There were few votes for women's rights here; the struggle for national independence was a priority.

Strategies and fighting methods

In all countries women first made their demands in newspapers and their own newsletters. Later they resorted to classic elements of lobbyism and public relations such as petitions and legislative initiatives. Women's rights activists in Protestant countries were very involved in collecting signature lists. In 1907, the women's suffrage association in Iceland was able to show 11,000 signatures from women, which roughly corresponded to the number of men entitled to vote. In only a few countries, as in Great Britain and the Netherlands, were street protests, demonstrations and vigils added to the protest repertoire at the beginning of the 20th century.

Educational work in the form of fictional stories and plays were widespread in Sweden; Switzerland used modern advertising media such as film and neon advertising in the 1920s. It was also popular to provide everyday objects such as thimble, pencil, dishes or pocket mirrors with the demand for women to vote. On most imaginative were the English suffragettes , who opened their own shops and a "corporate identity" with the colors green, white and purple developed ( g reen, w hite, v Iolet for " g ive w omen v ote" = dt. Give women the right to vote ).

French activists took individual acts of civil disobedience such as the tax boycott and the burning of the civil code , but they were unable to find a following. Only in Great Britain was there a mass movement. While the vast majority were moderate, a small minority became radical after 40–50 years of unsuccessful protests: They attacked MPs, threw window panes and started fires. Some responded to her arrest with a hunger strike.

Overall, it was important for the electoral movements to formulate their concerns in a culturally accepted framework. But if the prevailing gender image did not provide for a public appearance for women, new identities had to be created first, as in southern Europe, so that the demand for political participation became legitimate.

International networking

1904 was based in Berlin World Alliance for Women's Suffrage (Engl. International Woman Suffrage Alliance later International Alliance of Women ). One of his goals was to reduce the voting distance between the sexes. As is customary around the world, women's rights activists were divided on the question of whether they should simply demand a right to vote, as the men had (which could possibly be a census vote , a position held by prominent figures in the movement such as John Stuart Mill ), or whether they should everywhere demand the extension to equal and universal suffrage for men and women. The World Federation was an important engine that ensured global networking with its regular congresses and motivated individual women and groups from many countries to stand up for their rights. But it only accepted the respective umbrella organization of a state. For this reason, women from countries that did not exist as separate states at the time, such as Poland, the Czech Republic or the Baltic states, were not represented in the World Federation and found no hearing for their demand for national independence, which was often associated with political rights for women and men.

The socialist women were united in the " Women's International ". The first socialist women's congress was held in Stuttgart in 1907 under the direction of Clara Zetkin . The comrades demanded women's suffrage with the same urgency as the general men's suffrage for the lower social classes, in those countries in which it had not yet been implemented, other than at the national level. At the second meeting in Copenhagen in 1910, they decided to introduce International Women's Day as a "day of struggle" for women's suffrage. They organized the first demonstrations for women's suffrage in many countries.

Abolition of class or gender barriers

The path to universal women's suffrage ran parallel to the fiercely contested abolition of census suffrage for men. Only in a few countries was universal suffrage for both sexes introduced at the same time as in 1906 in the Grand Duchy of Finland, which was then part of Russia. The sooner men got the unrestricted right to vote, the longer the women had to wrestle for it. France and Switzerland became latecomer states because they were the oldest male democracies in Europe; The situation was similar in Greece and Bulgaria.

The social democratic parties were the first to include the demand for women's suffrage in their program. In its Erfurt program of 1891 , the SPD demanded “General, equal, direct suffrage and voting rights [...] regardless of gender for all elections and votes.” At its second party congress in 1903 , the Russian RSDRP accepted an almost identical demand . However, many workers feared that women's suffrage was an obstacle to enforcing full worker suffrage and saw contradictions between the emancipation of the working class and women.

In many states, the liberals sympathized with women's suffrage. What is decisive, however, is that liberal politicians often stuck to a census and made political participation dependent on social status or education. Accordingly, the majority of bourgeois women also demanded restricted voting rights for their gender. The main concern for them was the lifting of gender barriers, although some women’s rights activists only saw this as a first step to be followed by universal suffrage.

Each side of the political spectrum feared negative consequences for themselves. Socialists and liberals often believed that conservatives and clericals in particular would benefit from women's voting rights, while conservative parties invoked the danger that women would use their votes to strengthen left and liberal parties. They also saw women's suffrage as the first step towards complete emancipation . This was also one of the reasons why the lifting of the class barrier tended to prevail.

European developments

In central Europe, almost all countries introduced women's suffrage after the First World War. In most of these states, a complete upheaval took place around 1918, which included the introduction of universal suffrage for both sexes in the course of either a revolution or the establishment of a new state.

Most of the southern and southeastern countries gained women's suffrage after World War II and in the post-war period, with Belgium and France also falling into this timeline. In the Romance countries, where the civil code or a patriarchal, non-denominational legal system applied, the underage of women was more firmly anchored in society. Feudal-agrarian structures and the dominant influence of the church still shaped the gender order in the first half of the 20th century . In many southern countries the value of women's activities was only recognized in the resistance against the German occupation in World War II, whereupon they were given the right to vote as a “reward” or in return.

In Switzerland and Liechtenstein , the introduction of women's suffrage depended on a male referendum, which made the struggle of women very difficult. Because it was easier to protest against a decision of the government than against a "popular no".

Portugal and Spain were shaped by a long dictatorship of an authoritarian regime that prevented women from enjoying universal suffrage in Portugal and reversed earlier achievements in women's politics in Spain. In both countries, it was not until the end of the dictatorship in the mid-1970s that women came into possession of their civil rights. In other countries, too, authoritarian or fascist regimes such as Italy (until 1946) and Bulgaria prevented the implementation of general women's suffrage.

Anti-feminism

British reformers prevented women's suffrage in the Reform Act 1867 mainly because it could cause political differences within families between the spouses. For this reason, in Scandinavia and Great Britain, municipal suffrage was initially only introduced for single and widowed women - with the official reason that married women were already represented by their husbands.

Women faced gender barriers that did not affect men. In some Catholic countries such as Belgium, Italy and Orthodox Bulgaria, married mothers were granted local voting rights first because they were considered “more valuable” than childless women. On the other hand, the idea never occurred to make the eligibility of men dependent on the fathering of legitimate children. These had compulsory military service as a prerequisite for equal rights.

In order to minimize the supposedly unpredictable consequences of women's suffrage, the parliamentarians discussed all possible forms of a specifically female census. In some countries, such as Greece, a certain educational census has been introduced for women; in contrast to male voters, they had to provide evidence of schooling. In England, Hungary and Iceland women were temporarily subject to an age census, according to which they could only exercise their right to vote at the age of 30 and 40 respectively. Another form was the moral census, which initially denied prostitutes in Austria, Spain and Italy the right to vote.

Chronology of the introduction of women's suffrage in European countries

The years indicate the year in which unrestricted universal women's suffrage was introduced. In some countries there was previously restricted voting rights for women (e.g. only from a certain age, only for local elections, etc.).

- 1906 Finland

- 1913 Norway

- 1915 Denmark

- 1915 Iceland

- 1917 Russia

- 1917 Estonia

- 1918 Latvia

- 1918 Germany

- 1918 Austria

- 1918 Poland

- 1919 Luxembourg

- 1919 Netherlands

- 1920 Czechoslovakia

- 1921 Sweden

- 1928 United Kingdom

- 1931 Spain

- 1934 Turkey

- 1944 France

- 1945 Hungary

- 1945 Slovenia

- 1945 Bulgaria

- 1946 Italy

- 1974 Portugal

- 1948 Belgium

- 1952 Greece

- 1960 San Marino

- 1962 Monaco

- 1971 Switzerland

- 1984 Liechtenstein

See also

- Women's suffrage in Northern Europe

- Women's suffrage in Eastern Europe

- Women's suffrage in southern Europe

- Women's suffrage in Western Europe

- Women's suffrage outside Europe

- List of states by year in which women's suffrage was introduced

literature

- Bettina Bab; Gisela Notz ; Marianne Pitzen ; Valentine Rothe (Ed.): With power to choose! 100 years of women's suffrage in Europe. Frauenmuseum , Bonn 2006, ISBN 978-3-928239-54-7 , (publication for the exhibition of the same name in the Frauenmuseum, Bonn)

- Gisela Bock : The political thinking of suffragism: Germany around 1900 in an international comparison, in: dies .: Gender stories of the modern age. Ideas, politics, practice. Göttingen 2014, 168–203.

- Gisela Bock: Women in European History. From the Middle Ages to the present. Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 978-3-406-46167-5

- Sylvia Paletschek ; Bianka Pietrow-Ennker : Women's Emancipation Movements in Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century: Conclusions. In: Sylvia Paletschek; Bianka Pietrow-Ennker (Ed.): Women's Emancipation Movements in the Nineteenth Century. A European Perspective. Stanford University Press et al. A., Stanford Calif. u. a. 2004, ISBN 0-8047-4764-4

- Angelika Schaser , On the introduction of women's suffrage 90 years ago on November 12, 1918 , in: Feministische Studien 1 (2009), pp. 97–110 , ISSN 2365-9920 (online), ISSN 0723-5186 (print).

- Mariette Sineau: Law and Democracy. In: Georges Duby ; Michelle Perrot: History of Women. Volume 5: 20th Century. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1995, pp. 529-559 ISBN 3-593-34909-4

- Kari Uecker: It happened 100 years ago: For the first time, all Norwegians were allowed to vote. The right to vote came in stages and only after a long struggle . In: dialog . Announcements from the German-Norwegian Society e. V., Bonn. 32nd year 2013, No. 43, p. 23 (with reference to the exhibition on the anniversary in Oslo 2013, see also www.stemmerettsjubileet.no)

Web links

- Germany

- Women's suffrage in Germany. In: lwl.org

- 100 years of women's suffrage on the information portal on political education of the Federal Working Group on Political Education Online

- Austria

- Women's suffrage in Austria. Democracy Center Vienna

- Women's suffrage in Austria. In: onb.ac.at

- Switzerland

- Women's suffrage in Switzerland ( Memento from June 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Federal Agency for Civic Education: MW 04.03 Introduction of women's suffrage in Europe - bpb. In: bpb.de. October 26, 2012, accessed August 3, 2018 .

- ↑ In Article 64, cf. Archived copy ( memento of the original dated November 5, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. and Leon Trotsky: History of the Russian Revolution , Frankfurt am Main 1982, p. 303ff

- ↑ full text on Archive.org ; Brian Williams: Women Win the Vote. Cherrytree, London 2005

- ↑ Law of November 12, 1918 on the state and form of government of German Austria in the State Law Gazette in retro-digitized form at ALEX - Historical legal and legal texts online

- ↑ Call of the Council of People's Representatives to the German People (dokumentarchiv.de)

- ↑ Ordinance on the elections to the German constituent assembly of November 30, 1918 (dokumentarchiv.de)

- ↑ Wahlrechtslexikon von Wahlrecht.de on women's suffrage

- ↑ Angelika Schaser, On the introduction of women's suffrage 90 years ago on November 12, 1918 , in: Feministische Studien 1 (2009), pp. 97–110 , here pp. 107f.

- ↑ Article 10 of the Turkish Constitution of 1924 has been changed ( full text ( memento of the original from November 1, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice . )

- ↑ Christine Bard: Les Filles de Marianne. Histoire des féminismes. 1914-1940. Fayard 1995, p. 355

- ^ Yvonne Voegeli: Women's suffrage. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Women's suffrage. In: landtag.li , Landtag (Liechtenstein) , accessed on April 30, 2010

- ↑ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 289.

- ↑ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, Katherine Holden: International Encyclopedia of Women's Suffrage. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara, Denver, Oxford 2000, ISBN 1-57607-064-6 , p. 85.

- ↑ On the special path in matters of women's movement in detail Gisela Bock: The political thinking of suffragism: Germany around 1900 in an international comparison. In: dies .: Gender stories of the modern age. Ideas, politics, practice. Göttingen 2014, 168–203.

- ^ Gisela Bock: The political thinking of suffragism: Germany around 1900 in an international comparison. In: dies .: Gender stories of the modern age. Ideas, politics, practice. Göttingen 2014, 168–203, here p. 179.

- ↑ Storjohann: Suffragette Power - women in power for 100 years! January 21, 2018, accessed on November 7, 2019 (German).

- ^ Carole Pateman: Beyond Suffrage. Three Questions About Woman Suffrage, in: Caroline Daley u. Melanie Nolan (Ed.): Suffrage and Beyond. International Feminist Perspectives. New York 1994, pp. 331-348, here p. 334.

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/deutsch/geschichte/deutsch/spd/1891/erfurt.htm

- ↑ http://www.scientific-socialism.de/Programm1903.htm

- ↑ Catherine Hall; Keith McClelland; Jane Rendall: Defining the Victorian Nation: Class, Race, Gender and the British Reform Act of 1867 , Cambridge University, 2000, ISBN 0-521-57218-5

- ↑ Introductory dates for women's suffrage in 20 European countries. German Bundestag, accessed on September 22, 2018 .