Foot traffic

Foot traffic is the covering of paths by people walking. A pedestrian , even pedestrians , is a man who to walk goes .

About the terms

Pedestrian is a general term that can also be applied to walkers and hikers . Wheelchair users also refer to non-wheelchair users as pedestrians.

- A pedestrian is understood in the legal sense to mean a road user who does not use any technical means of transport . No distinction is made between a walking and a running pedestrian. A pedestrian is also allowed to transport loads with a handcart or push cart . Since April 1, 2013 in the German road traffic regulations of the purposes of gender-neutral language of walking foregoing spoken.

- The term passerby describes a pedestrian in a specific role.

- In sports is between walking and Running species distinguished.

Pedestrian traffic is generally that part of transport and travel that takes place without a means of transport.

- In the legal sense, it is the covering of paths on public roads, paths and squares. Pedestrian traffic today includes every movement made by one's own strength without technical aids that are legally considered a vehicle or with vehicles that are expressly not allowed to participate in road traffic .

The term per pedes comes from Latin , which is still widespread at least in German-speaking countries and means "on foot".

Cultural history of walking

Military importance

With the emergence of the great empires, when larger armies were set up for the first time , armies had to walk as it would not have been logistically possible to equip every soldier with a horse. Foot armies, later called infantry , could cover up to 30 km a day with full gear.

Pedestrian traffic in conflict with other forms of transport

Roads have always been intended for all types of transport and are characterized by a wide range of uses. In addition to transport, trade, handicrafts and communication took place on the street; the street was an extension of living and working space. In places where there were conflicts with wagon or rider traffic, sidewalks were set up at an early stage. Sidewalks as well as pedestrian crossings were developed in the Roman road construction industry. The latter were designed in the form of stepping stones, like all traffic systems in the entire Roman Empire, for a standard lane width.

The narrower the street space and the more traffic there was, the greater the conflicts. As early as 1563, the parliament in France asked the king in vain to ban vehicles on the streets of Paris. Even without a motor vehicle, it was problematic for pedestrians, as Goethe describes a carriage ride through Naples: “The driver incessantly shouts 'Place, place!' So that donkeys, wood or rubbish-carrying carts rolling towards you, people, children and old people who are dragging or walking freely, watch out , evade, but continue the sharp trot unhindered. "( Goethe )

Walking as a leisure activity

In bourgeois industrial society, walking and strolling developed as leisure activities. The conflict about the traffic areas was also a dispute between the upper and lower social classes, because the rulers sat in the carriages. The Enlightenment and the French Revolution also brought an emancipation of the pedestrian and a heyday of walking and strolling. In Paris in 1789, the idea of a pedestrian republic was born. The sidewalk was part of the call for civil rights and emancipation of the middle class (that's why he also citizens sidewalk).

The heyday of the sidewalks came with the financial takeover of power by the bourgeoisie. Especially the late nineteenth urban development was characterized by wide walkways. “After all, in large cities, in the interests of greater convenience for the public and to make the activity of pickpockets more difficult, sidewalks less than 4 m wide should no longer be laid”, wrote Brix in 1909. The sidewalk was an important part of the street design, with the scale of the street and buildings being a prerequisite and degree of urban development. Boulevards and promenades were an expression of the self-confidence they had gained. According to Stübben , the driveway should, if possible, be restricted to half the width of the street, and the sidewalks should thus each make up a quarter of the street width. "This arrangement combines a friendly appearance with the reduction of the investment costs.")

Pedestrians and automobiles

With the advent of the automobile as a means of mass transportation, pedestrians were increasingly restricted in their mobility from the beginning of the 20th century. In the sense of a car-friendly city , they were banished to pedestrian paths (including sidewalks , sidewalks or sidewalks ) in many places by road regulations . After all, in the 1970s, at least in many European inner cities, pedestrian zones were created in which pedestrians can walk undisturbed, at least outside of delivery times. In order to make it possible to cross busy roads, pedestrian bridges that are not protected from the weather and often poorly lit pedestrian underpasses were built in many places . The latter offered the ideal environment for the emergence of new youth subcultures. From the 1980s, pedestrian safety also became an important planning criterion when carrying out road construction work . In the last two decades there have also been increased efforts by associations and town planners to regain space for pedestrians. Rural areas in particular have a lot of catching up to do here, however, since the automobile is seen as an indispensable means of transport there, and accordingly little consideration is given to the needs of pedestrians in traffic planning.

The use of the lanes by pedestrians was self-evident and was even expressly z. B. mentioned in the road ordinance for West Prussia of 1905:

"Driveways may be used by anyone for walking, riding, cycling, driving and driving cattle, cycle paths only for cycling, footpaths, without prejudice to private rights for other uses, only for walking."

The displacement of pedestrians from the street only began with the advent of the automobile. "From all sides, in every place and at any time in the big city, the horn of the automobile goes off at its victims." ( Pidoll, 1912 ) The high speeds for the conditions at the time and the mixed use of the streets (allowed in Prussia in 1910 15 km / h) led to numerous accidents. In Berlin, with just 5,613 automobiles, a total of 2,851 automobile accidents occurred from October 1910 to the end of September 1911, 67 of which were fatal.

This displacement process was problematic; there was again a conflict between “above” and “below” and there were violent backlashes, as Bierbaum describes in his travelogue from 1902: “Never in my life have I been cursed as much as during my automobile trip in 1902. All of them German dialects from Berlin to Dresden, Vienna, Munich to Bozen were involved and all dialects of Italian from Trento to Sorrento - not counting the silent curses, as there are: shaking fists, sticking out the tongue, showing the rear and other things . "

The “rear view” is also all too understandable if one reads the diary note from Rudolf Diesel's 1905 journey : “No, what kind of dust we made when we left Italy. I haven't seen anything like it in my entire life. Mealy lime dust lay two inches thick on the street. Thereupon Georg chased what the wagon gave through the valley of the Piave, and behind us an enormous cone spread out. ... We shocked the pedestrians as if with a gas attack, their faces contorted, and we left them behind in a world that had become shapeless, in which fields and trees had lost all color under a layer of dry powder. "

In the 1920s, approximately 17,000 to 18,000 people died annually in car accidents in the United States, three quarters of them pedestrians. Half of the pedestrians were children. The public was appalled and the victims were honored with lavish funeral services. As a result of these deadly conflicts of use, anti-car associations were founded and cities began to build traffic obstacles such as thresholds in the roadway. In 1923, the city of Cincinnati began developing ideas to technically limit the maximum speed of cars. These developments have caused increasing concern among motorists and manufacturers as they threatened the breakthrough of the automobile. As a countermovement, the “Motordom” association was founded by driver associations, vehicle manufacturers and automobile dealerships, with the aim of promoting automobilization and working towards a change in laws that prevented this. Through numerous PR and lobbying measures, Motordom caused a fundamental reinterpretation of the situation that had existed for thousands of years, according to which streets were available across their entire width for the mobility needs of everyone.

Motordom invented the catchy battle term of "jay walking", which the club was committed to fighting. Jay means "inexperienced", but was also generally associated with the simple rural population. According to Motordom's interpretation, the drivers were also to blame for accidents, but mostly and above all inexperienced "country eggs " who thoughtlessly ran in front of the car. Irresponsible parents are also a problem because they let their children near streets. The fact that the streets had been available to pedestrians and children playing for thousands of years was deliberately ignored. As a result of this massive lobbying work, which was accompanied by flyer and poster campaigns, political leaders soon began to rethink. Many cities in the United States have now passed regulations against "jay walking" and imposed heavy penalties. As the country with the greatest degree of motorization, the USA played a pioneering role in the world. Soon similar regulations were enacted in many other countries around the world, in Germany in 1934 with the Reich Road Traffic Act.

This regulated road traffic for the first time for the entire Reich territory. "If a road is clearly intended for individual types of traffic (footpath, cycle path, bridle path), this traffic is limited to the part of the road assigned to it, the rest of the traffic is excluded." Within a few decades, the car had prevailed, which at the beginning During the 20th century, it was still perceived as an intruder into the city streets, which were then used in many ways. Pedestrians were only allowed to use the part of the street assigned to them.

The objective of the Reich Road Traffic Regulations was described in the preamble: "The promotion of the motor vehicle is the objective set by the Reich Chancellor and Führer, which this regulation is also intended to serve."

With the increase in motorization after the Second World War - in 1953 there were again almost 1.2 million passenger vehicles in Germany - the possibility of sidewalk parking was explicitly included in the new road traffic regulations (StVO) of 1953 in order, as the reason stated, to regulate the question of parking on sidewalks, which has not been uniformly answered in the case law, by law. In the new version of the StVO from 1970, the possibility of a shared cycle and footpath was added. Progress was made in 1964 with the introduction of priority for pedestrians at zebra crossings in the StVO, the establishment of pedestrian zones (in narrowly limited areas) and the introduction of traffic-calmed zones.

The change in walking culture

Walking is a natural form of human locomotion. In the form of an upright gait, it has developed into a characteristic appearance of humans in the course of evolution . As has been the case for decades in the USA, however, pedestrians outside the city centers are increasingly disappearing from traffic in Europe. This observation prompted W. Wehap in the "Graz Contributions to European Ethnology " to state that walking would no longer be "the natural way of getting around for the masses", but that it was experiencing a renaissance under different circumstances, with pedestrians too encourages a confident demeanor. SA Warwitz sees an increasing recovery of foot traffic in the sporting field, which is motivated by a growing health awareness and playful interests: The public roads are increasingly used by all age groups for jogging, wogging, Nordic walking, hiking, marching, skating or scooters . According to Warwitz, the “walking culture” is not in a phase of decline, but in a process of change in which new forms of activity are discovered. This development towards a new "walking ability" is encouraged right from the start of school, because the rediscovery of walking culture by the children includes not only the physical element, but also shared experience and communication with people of the same age at "walking pace" on the way to school and on class hikes organized according to children .

see also:

Foot traffic data

Today's importance of foot traffic

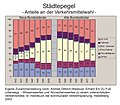

The importance of foot traffic in traffic has decreased significantly in the late 20th century. For example, while in West Germany in 1972 33% of all trips were made exclusively on foot, in 1982 it was just under 30%. However, in this century it has stabilized. According to the surveys on mobility in Germany, it had a share of 23% in 2002, a share of 24% in 2008 and a share of 22% in 2017. Jena - a “city of short distances” - holds a top position in Germany in terms of the proportion of pedestrians in total traffic (39.3 percent, 2008; with an increasing trend since 2003). If only the choice of means of transport in cities since 1972 is considered, the change is particularly clear (see figure city level). Comparable studies on the choice of means of transport were carried out in both the GDR and the FRG. While pedestrian traffic was the dominant mode of transport in cities until the mid-1960s, the share of walking has decreased significantly since then.

The causes of the decline in the late 20th century are diverse:

- Changed settlement structures: The settlement structures are often designed to be almost exclusively accessible by motor vehicle. The goals have moved into the distance. Grocery stores that used to be within walking distance now have to be approached by motor vehicle because local supplies are increasingly thinned out.

- The centralization of public institutions such as schools leads to further routes: the accompanying traffic increases. In 2017, for example, children between the ages of 7 and 10 covered 35% of their journeys on foot, compared with 41% as passengers in motor vehicles. The delivery and holding service of parents by car (" parent taxi ") has taken on considerable dimensions.

- Changed lifestyles and values: Mobility culture today is almost exclusively limited to “sheer driving pleasure”. At the beginning of the twentieth century there was a whole genre of literature that dealt with strolling in the cities. Mobility culture is a foreign word in most cities, also in the context of city marketing.

- The conditions for pedestrians are often modest. Often they only have leftover space available today. Many wide sidewalks z. B. the generous Wilhelminian style urban development are used today for parking or for bike paths.

- Political decision-makers and planners often do not perceive foot traffic as a relevant mode of transport.

These developments partly continued in the 21st century, but there were also opposing trends that slowed the decline in foot traffic and partly reversed it:

- Urbanization and densification: Numerous cities are recording growing numbers of inhabitants and higher building densities. This means that a growing number of destinations can often be reached on foot in terms of time and space.

- The proportion of older people in the population is growing. As people get older, foot traffic becomes more important. In 2017, 40 to 50 year olds covered 17% of their journeys on foot, 65 to 75 year olds 29% of their journeys and those over 80 years of age 34% of their journeys.

- Cities are improving the conditions for pedestrian traffic. Starting in 2016, twelve model cities took part in the “Municipal Foot Traffic Strategies” project, initiated by the Federal Environment Agency and implemented by the Fachverband Fußverkehr Deutschland FUSS e. V. Leipzig was the first major city in Germany to create a municipal commissioner for pedestrian traffic. The Berlin Senate announced the adoption of a separate section on “foot traffic” in the state's mobility law for 2020.

- The appreciation of walking among people is still high. In 2017, 84% of those surveyed in metropolitan areas were satisfied with the conditions for walking, but only 71% with public transport, 51% with car traffic and 48% with bicycle traffic. Motives for walking are both individual (e.g. simplicity, costs, experience, health) as well as socio-ecological (urban compatibility, environmental protection, climate protection).

- In many locations, brick-and-mortar retail mainly lives from customers who come on foot. The number of pedestrians in a street, the so-called pedestrian frequency , is an important indicator of the market value as a shopping location. International studies show that some of the dealers have so far overestimated the proportion of sales they make with customers who come by car and at the same time overestimate the proportion of customers who come on foot and their sales.

Pedestrian accident risks

Pedestrians do not belong to the high-risk groups in public transport in absolute terms, due to the relatively lower overall participation . In Austria in 2007, pedestrians only accounted for around 8% of the injured, but more than 15% of the road deaths. The risk and severity of injury is consistently extremely high: 93% of the pedestrians involved in accidents were injured, a quarter (25.1%) of all those who had an accident were seriously injured or killed (in comparison: total: 59.2% / 15.5%; cars - Occupants: 52.4% / 9.6%; but motorcycle 91.7% / 34.7%). Pedestrian accidents are primarily a problem in the local area , where 12% of all injuries but 40% of all fatalities were on foot.

According to a study by the Austrian Road Safety Board of Trustees from 2008, which does not evaluate the traffic accident statistics, but rather subsequent legal proceedings with regard to the question of debt , it shows that the main culprit in fatal traffic accidents involving unprotected road users (including cyclists ) is 50% with pedestrians ( or steering arms). Two reasons are given for this quite unexpected result:

- On the one hand, negligence due to factors such as stress or excessive demands : the main cause of death is crossing the road away from protected paths or crossings ; one fifth of all fatal accidents occur after ignoring a red traffic light or disregarding the priority of privileged road users (usually cars).

- On the other hand, there is the high percentage of alcohol consumption, which accounts for 10% - previous estimates were 6–7% - in fatal accidents (all road users): Even if pedestrians are drunk in traffic, courts rate their own fault as 100%, regardless of fault of the other parties involved.

Among the group of pedestrians, the group of young people aged 5–19 years (27%) turned out to be the main at risk - also for Austria - for injuries, and senior citizens aged 65 and over (almost 50%) for fatal accidents.

In German criminal law, according to § 19 StGB, children under 14 years of age use the non-judgmental term causer instead of culpability because of the lack of responsibility , which also has criminal consequences for the other parties involved in the accident. According to the surveys published annually by the Federal Statistical Office, there has been a shift in accidents with children in Germany in the direction of passenger accidents in motor vehicles for several years. In 2007, these accounted for 43% of the fatal accidents and thus exceeded both bicycle and pedestrian accidents. In 2015, children between the ages of six and nine were still the most likely to have accidents in a car (41.5%). Most of the children killed lost their lives as passengers in a car (40.5%). The trend towards dangerous vehicle transport (keyword school rush hour ) is countered with consistent pedestrian education and measures such as the Karlsruhe 12-step program and the acquisition of the pedestrian diploma by schools. At the same time, educational events convey to parents that their children, as trained independent pedestrians, are demonstrably better protected in traffic than by car transport.

Road traffic regulations

Germany

In Germany , the regulations relevant for pedestrians can be found in Section 25 of the Road Traffic Regulations (StVO).

Use of the sidewalks

The use of sidewalks for pedestrians is regulated in Section 25, Paragraph 1 of the Road Traffic Regulations (StVO): “If you walk, you must use the sidewalks. You can only walk on the lane if the road has neither a sidewalk nor a hard shoulder. ” However, you must not hinder other pedestrians with bulky objects or vehicles. Paragraph 2 states: "Anyone who walks and carries vehicles or bulky objects must use the lane if other people walking on the sidewalk or on the hard shoulder would be significantly impeded." Pedestrians are not allowed to use motorways and motorways .

In the StVO or other laws and ordinances, there are no regulations whatsoever for moving or staying by pedestrians on the sidewalk, e.g. commands to walk to the right or left, to walk one behind the other, to grant an operation analogous to the right of way on the lane, to change direction, to Stop or go to speed.

Vehicles are not allowed to use the sidewalks. This results from § 2 StVO: "Vehicles must use the lane ..." . According to § 12 StvO, motor vehicles are also prohibited from parking on sidewalks, but bicycles may be parked on sidewalks if traffic is not obstructed.

There is an exception for children with bicycles. Children up to 8 years of age must, older children up to 10 years of age are allowed to use sidewalks with bicycles. One supervisor may also use the sidewalk by bike for the duration of the accompaniment. Special consideration must be given to pedestrians.

“Special means of transport” ( § 24 StVO ) are not designated as vehicles . This includes push and reach wheelchairs, toboggans, strollers, scooters, children's bicycles and similar means of transport such as inline skaters. Unless otherwise regulated, you have to use the sidewalks with these.

At intersections and junctions

In general, according to Section 25 (3) of the StVO , pedestrians have to cross the lanes quickly on the shortest route across the direction of travel, taking into account vehicle traffic, and if the traffic situation requires it, only at intersections or junctions, at traffic lights within markings or on pedestrian crossings (Sign 293). If the carriageway is crossed at intersections or junctions, pedestrian crossings or markings on traffic lights ( pedestrian ford ) must always be used. Priority regulations for pedestrians are complicated at intersections and junctions, depending on which part of the lane they are on and whether the vehicles are turning or driving straight ahead. The rules of conduct for drivers when turning are laid down in Section 9 (3) of the StVO :

“If you want to turn, you have to let oncoming vehicles pass through, rail vehicles, bicycles with auxiliary engines and cyclists even if they are driving in the same direction on or next to the road. This also applies to regular buses and other vehicles that use specially marked lanes. He must show special consideration for pedestrians; if necessary, he has to wait. "

Pedestrians always have priority over vehicles turning off. This applies regardless of whether the intersection or confluence is marked with right of way signs or not. Pedestrians do not have priority over vehicles that do not turn (see illustration). If traffic lights are installed at the intersections and junctions , pedestrians must pay attention to the traffic light signals. If green changes to red while pedestrians cross the lane, they have to continue on their way quickly. For vehicles turning off, the rules of conduct described in Section 9 (3) of the StVO apply when turning, including at traffic lights.

The foot traffic at the green arrow requires special attention .

Austria

According to the Austrian road traffic regulations , pedestrians have to use the sidewalk ( § 76 StVO). If this is missing, they have to go to the street banquet; this is also missing, at the very edge of the road. On open roads they have to use the left side of the road - except in the case of unreasonableness. This also applies to people pulling strollers or wheelchairs. However, porters are only allowed to use sidewalks and street banquets if they do not unduly obstruct pedestrian traffic. In the local area near construction sites, farms or gardens, sidewalks may also be used lengthways with wheelbarrows.

According to ( § 78 StVO), disabilities caused by the distribution of programs, carrying billboards, bringing animals and the like are prohibited, but also by standing still for no reason.

Pedestrians who want to cross the streets must use existing protective paths or overpasses or underpasses. Only if these are missing or are more than 25 meters away, the road may be crossed in other places; in the local area, however, only if the traffic situation "undoubtedly permits" a safe crossing. In general, the shortest route and an “appropriate speed” should be chosen.

Switzerland

For a long time, Swiss pedestrians were unnecessarily unsettled by the mandatory hand signals in the traffic regulations. However, under pressure from the Swiss Federal Supreme Court, this situation was clarified by the legislature in 1994 (see zebra crossing ).

United Kingdom

In Great Britain, rules 1 to 33 of the Highway Code regulate the behavior of pedestrians in traffic. However, based on the Anglo-American understanding of law, these should be understood more as advice. However, this does not apply to the following points:

- Pedestrians are not allowed to walk on motorways and slippery roads, unless it is an exceptional situation (Laws RTRA sect 17, MT (E&W) R 1982 as amended & MT (S) R regs 2 & 13);

- Pedestrians are not allowed to jump on moving cars or hold onto moving cars (Law RTRA 1988 sect 26);

- Pedestrians are allowed at crosswalks and so-called Pelican or Puffin Crossings not wander (Laws ZPPPCRGD reg 19 & RTRA sect 25 (5)).

Road construction guidelines

In 2002, the Research Association for Roads and Transport (FGSV) published the recommendations for pedestrian traffic systems - EFA 2002 in Germany. In Austria, the RVS 3.12 - Pedestrian Traffic Information Sheet was published in August 2004 by the Research Association for Roads and Traffic .

Paths for pedestrians

The establishment of the traffic routes for pedestrians is subject to traffic planning , for pedestrians to spatial planning . The routes for pedestrians in urban areas can be divided as follows:

- independently guided footpaths ( sidewalks ) or non-passable residential paths

- Pedestrian areas ( pedestrian zone ) in streets and in squares

- sidewalks along the street

- Traffic-calmed areas

- in Austria: mixed walking and cycling paths

Other facilities for pedestrian traffic on public roads are the pedestrian ford , pedestrian crossing and the encounter zone , which is very successful in Switzerland and has recently also been tested in Germany and Austria .

Safety guidelines outside of public transport

In particular at large public events or during the evacuation of larger buildings, comparatively high densities of up to ten people per square meter can result. Understanding the dynamics and the collective and emergent phenomena that arise from one person per square meter through the mutual influence of the people is of crucial importance for the emergency safety of such places. By correctly considering such phenomena in evacuation simulations, attempts are now being made to ensure the safety of any complex and any large building structure during the planning phase.

Pedestrian initiatives

FOOT e. V. German Pedestrian Association

In Germany, the Fachverband Fußverkehr Deutschland Fuss e. V. the interests of those who walk. It sees itself as a lobby organization, professional competence center and umbrella for local initiatives that want to promote pedestrian traffic. Paul Bickelbacher (Munich), Katalin Saary (Darmstadt) and Roland Stimpel (Berlin) were elected as board members in 2019 . Stefan Lieb from Berlin has been Federal Managing Director since April 2015.

Pedestrian traffic in Switzerland

In Switzerland there since 1972 the Association pedestrian foot traffic Switzerland , which the target has set to be the center of excellence for pedestrian traffic in residential areas and the needs of pedestrians in the transport policy to introduce. It supports the Confederation and the cantons in implementing the Swiss Footpaths and Hiking Trails Act . He is also committed to innovative, pedestrian-friendly traffic design, for example by creating meeting zones.

The association advertises the foot price at regular intervals, which awards projects that improve the situation of pedestrians in road traffic. This is an open invitation to tender, which means that experts from all cantons can participate. At the last award ceremony, Grenchen received the award as the most pedestrian-friendly city in Switzerland.

Walk-space.at - The Austrian association for pedestrians

Walk-space.at is an independent Austrian association that represents the “interests of pedestrians”. Every year the association organizes specialist conferences at various locations in Austria.

Actions and initiatives

At the end of the 1980s Michael Hartmann from Munich invented carwalking , walking over cars parked on the sidewalks without damaging them. By streetwalking - walking on the street without recognizing the priority of cars - he tried to adapt road traffic to the needs and speeds of pedestrians again. Hartmann also spread his ideas in traffic seminars and a book. His direct actions against car traffic temporarily gained a certain amount of media attention and also found a few imitators. But they also earned him hospital stays and admissions to psychiatric institutions. In court hearings, he was usually able to obtain acquittals. After Hartmann moved abroad, the carwalking scene fell asleep.

The Laufbus or Gehbus campaign is intended to encourage schoolchildren to walk so that they can get enough exercise in everyday life and learn to travel independently and in an environmentally friendly manner.

In order to protect the particularly endangered school starter on their first independent footsteps to school, traffic education has created initiatives such as the school route plan or the school route game , which the children themselves are involved in developing. Cities and municipalities are also increasingly making children's city maps available, which make it easier for children to find their way around their district.

In October 2018, the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) presented the first basic features of a nationally planned walking strategy. The offensive should, among other things, increase the number of footpaths by half by 2030, make pedestrian traffic overall safer and more accessible, and increase the quality of stay for pedestrians. As part of the strategy, for example, the following measures could be implemented (UBA proposals): Introduction of the regular speed of 30 km / h in urban areas, increasing fines for anti-pedestrian behavior or anchoring pedestrian accessibility in planning law.

literature

- Jennifer Bartl: Go. An investigation into walking as appropriation of urban space . Diploma thesis, Vienna University of Technology 2007 ( full text )

- Dirk Bräuer, Werner Draeger, Andrea Dittrich-Wesbuer: Foot traffic - a planning aid for practice . Institute for State and Urban Development Research - Module 24, Dortmund 2001, ISBN 3-8176-9024-X .

- Dirk Bräuer, Andreas Schmitz: Basics of pedestrian traffic planning . In: Handbook of municipal transport planning. Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-87907-400-3 .

- Andrea Dittrich-Wesbuer, Erhard Erl: Out and about on foot - what is worth knowing and what is desirable about an underestimated means of transport . In: Handbook of municipal transport planning. Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 3-87907-400-3 .

- John J. Fruin: Pedestrian Planning and Design. Metropolitan Association of Urban Designers and Environmental Pl.anners. 1971.

- Sebastian Haffner : The life of pedestrians. Feuilletons 1933–1938 , Munich 2004.

- Institute for State and Urban Development Research of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia - ILS (Hrsg.): On foot mobile . Dortmund 2000, ISBN 3-8176-6158-4 .

- Johann-Günther König: On foot. A story of walking . Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-020297-5 .

- Rita Pfeiffer: We GO to school. Vienna 2007

- Angelika Schlansky, Roland Hasenstab, Bernd Herzog-Schlagk: Walking moves the city - the benefits of pedestrian traffic for urban development . Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-922504-42-6 .

- Federal Statistical Office (Ed.): Statistisches Jahrbuch 2016. Child accidents in road traffic 2015, Wiesbaden 2016, ISBN 978-3-8246-1049-5 (row 7: traffic accidents / annual results)

- Siegbert A. Warwitz : The pedestrian diploma . In the S. Traffic education from the child . 6th edition, Baltmannsweiler 2009, pp. 221-251. ISBN 978-3-8340-0563-2 .

- Wolfgang Wehap: Walking culture - mobility and progress from a walking perspective since industrialization . Frankfurt 1997.

- Ulrich Weidmann: Pedestrian Transport Technology. IVT series of publications No. 90, 2nd edition, ETH Zurich, Zurich March 1993 [1]

media

- Our fate as pedestrians , SWR2 - Forum , August 22, 2007: Conversation between Matthias Hahn ( Mayor of Stuttgart ), Felicitas Hoppe (writer and pedestrian in Berlin-Mitte ) and Heiner Monheim (German transport scientist, geographer , professor emeritus at Trier University )

- The last pedestrian , comedy film with Heinz Erhardt , Germany 1960

Web links

- Federal Environment Agency: Foot traffic , accessed on August 29, 2018

- fussverkehrsstrategien.de , accessed on August 29, 2018

- fussverkehr.de: Working group on foot traffic from SRL and FUSS e. V. , 2009, pdf, accessed on August 29, 2018

- nach-rom-zu-fuss.de, About walking: Journalistic texts about walking

Individual evidence

- ↑ New gender-neutral StVO: Dumb German in road traffic - SPIEGEL ONLINE. Retrieved November 6, 2018 .

- ^ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von: Italienische Reise . Cologne 1998, p. 208

- ↑ Josef Stübben: Urban planning . Leipzig 1924

- ↑ Road Regulations for the Province of West Prussia of September 27, 1905. In: Law Collection for the Royal Prussian States, Vol. VII, 1900–1906, p. 682

- ↑ Michael Freiherr von Pidoll: Today's automobilism. A protest and a wake-up call. Vienna 1912, p. 1

- ^ Otto Julius Bierbaum: A sensitive journey in the automobile. From Berlin to Sorrento and back to the Rhine. Berlin 1903

- ↑ quoted from: Wolfgang Sachs: Die Liebe zum Automobil. A look back at the history of our desires. Reinbek 1984

- ↑ Holger Holzer: How the car became the boss on the street. In: Welt.de. June 14, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2017 .

- ^ Sarah Goodyear: The Invention of Jaywalking. April 24, 2012, accessed October 19, 2017 .

- ↑ W. Wehap: Gehkultur - mobility and progress from walking sight since industrialization . Frankfurt 1997

- ^ Siegbert A. Warwitz: Traffic education from the child . Baltmannsweiler 6th edition 2009. pp. 51–56

- ^ Siegbert A. Warwitz: Traffic education from the child . Baltmannsweiler 6th edition 2009. pp. 190–221

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure: Mobility in Germany 2017. Accessed on October 29, 2019 .

- ↑ Gerd-Axel Ahrens: Special evaluation of the traffic survey 'Mobility in Cities - SrV 2008' Comparison of cities. (PDF; 1.25 MB) November 2009, accessed on December 27, 2014 (research project of the Technical University of Dresden).

- ↑ Federal Minister of Transport and Infrastructure: Mobility in Germany 2017. Accessed on October 29, 2019 .

- ↑ FUSS e. V. Fachverband Fußverkehr Deutschland: Walking socially: The basis of all mobility. Retrieved October 29, 2019 .

- ↑ Municipal foot traffic strategies. FOOT e. V. German Pedestrian Association, accessed on October 29, 2019 .

- ↑ "Foot traffic finds friends everywhere". Retrieved October 29, 2019 .

- ↑ Federal Minister of Transport and Infrastructure: Mobility in Germany 2017. Accessed on October 29, 2019 .

- ^ André Eberhard: Germany: pedestrian frequency - Hanover and Stuttgart clear winners, Leipzig in the top 10. In: gewerbeimmobilien24.de. July 19, 2008, archived from the original on August 1, 2008 ; accessed on December 27, 2014 .

- ↑ FUSS e. V. Fachverband Fußverkehr Deutschland: Economy: Low costs - many customers. Retrieved October 29, 2019 .

- ↑ Kuratorium für Verkehrssicherheit (Ed.): Traffic accident statistics 2007 (= series Verkehr in Österreich . Issue 40). May 2008, ISSN 1026-3969 ( online [PDF]). Traffic accident statistics 2007 ( Memento of the original from July 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ 4201 of a total of 53,211 injured; 108 out of a total of 691 fatalities, in 644 accidents with fatalities; according to KfV 2007, p. 25 injured / killed by traffic involvement and p. 31 injured and killed pedestrians by type of road

- ↑ Pedestrians: Persons involved in the accident: 4504; Casualties: 4309, injured (total): 4201, of which seriously injured: 972; according to KfV 2007, p. 26 Severity of injury according to traffic involvement

- ↑ KfV 2007, p. 27 Injured persons in the local area and in the field , p. 28 Fatalities in the local area and in the field

- ^ Fritz Pessl: Pedestrians as the greatest risk . In: Salzburger Nachrichten . August 14, 2008, p. 5 .

- ↑ 5-9: 321, 10-14: 419, 15-19: 414, together: 1154; According to KfV 2007, p. 32 Injured pedestrians by age group and gender

- ↑ KfV 2007, p. 33 Pedestrians killed by age group and gender

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office (ed.) (2009): Traffic accidents. Children's road accidents in 2008 . Wiesbaden

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office (ed.) (2008): Traffic accidents. Child traffic accidents in 2007 . P. 4

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office (Ed.): Statistisches Jahrbuch 2016. Child accidents in road traffic 2015 , Wiesbaden 2016, p. 8)

- ^ Siegbert A. Warwitz: The pedestrian diploma . In the S. Traffic education from the child . 6th edition, Baltmannsweiler 2009, pp. 221-251

- ↑ Rita Pfeiffer: We GO to school. Vienna 2007

- ↑ Administrative regulation for the road traffic regulations

- ^ Judgment by the Lower Saxony Administrative Court; Parking of bicycles on a station forecourt

- ^ Research Society for Roads and Transportation - FGSV: Recommendations for Pedestrian Traffic Systems - EFA 2002 . Cologne 2002

- ^ Research community for road and traffic: Leaflet RVS 3.12 Pedestrian traffic . Vienna 2004

- ↑ foot e. V.

- ↑ FUSS e. V. German Pedestrian Association: Heads and committees. Retrieved October 29, 2019 .

- ↑ http://www.berliner-zeitung.de/ueber-berlin-reden/fussgaengerlobbyist-stefan-lieb--warum-radfahrer-in-berlin-nerven-koennen,20812554,31322344.html

- ↑ Foot traffic in Switzerland

- ↑ Association Foot Price

- ↑ Walk-space.at

- ↑ Michael Hartmann: Der AutoGeher. AutoBiography of a car opponent. ISBN 3-928300-81-4

- ↑ Carwalking: Description

- ^ BGH verdict in the Tagesthemen of August 31, 1995

- ^ Judgment of the Federal Court of Justice of August 31, 1995

- ^ Judgment of the Berlin Regional Court of April 1, 1997

- ↑ Umweltbundesamt Deutschland ( Memento of the original from October 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Increase foot traffic, protect the environment, make cities liveable . Umweltbundesamt.de. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ↑ podster.de ( Memento of the original from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (March 21, 2017)