Old Town (Munich)

The Munich's Old Town is the district of the Bavarian capital, Munich , is one of the longest to the city, although some places that now quarters of Munich are, have long been documented before Munich. Together with the Lehel district, the old town forms the No. 1 district of Altstadt-Lehel . The entire area of the old town is entered in the Bavarian list of monuments both as a listed ensemble and as a ground monument (archaeological monument) .

location

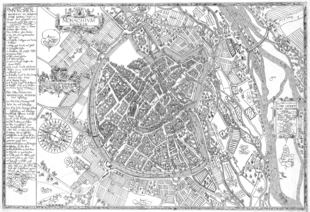

The old town district of Munich essentially corresponds to the area of the historic city center of Munich, i.e. the area that was surrounded by Munich city fortifications from the Middle Ages to the end of the 18th century . It lies on two terrace steps of the Munich gravel plain, the Hirschauterrasse, which formed the original flood bed of the Isar, and the old town terrace , only a few meters higher, on which the original city was founded. The slope edge runs roughly along the west side of Oberanger, Rosental, Viktualienmarkt, Sparkassenstrasse and Marstallplatz and separates the upper and lower courtyard gardens .

The border of the old town is essentially formed by the old town ring. Exceptions are the Galeriestraße - Odeonsplatz - Brienner Straße within the Altstadtring in the north and the Müllerstraße – Rumfordstraße street outside the Altstadtring in the southeast. The old town borders on four districts, which originally represented the continuation of the historic districts outside the city wall: in the northeast the Lehel , formerly also called St. Anna-Vorstadt or outer Graggenauer Viertel, in the southeast the Isarvorstadt , formerly also called outer Angerviertel, im In the southwest the Ludwigsvorstadt , formerly also called the outer Hackenviertel, and in the northwest the Maxvorstadt , formerly also called the outer Kreuzviertel.

Surname

In Munich, “Altstadt” is not - as in Landshut or Straubing , for example - a historical place name to distinguish it from a new town. The term was used descriptively from the 19th century to distinguish the historic city center, i.e. the area within the original city walls, from the newly created suburbs.

The name was first used as a toponym after the Second World War, when, with the introduction of the district committees, names were sought for the Munich boroughs that were supposed to replace or at least supplement the earlier denominations of the boroughs with numbers. The name was then officially decided in 1954 by the Munich city council as Altstadt-Nord for the merger of the previous city districts 1 and 4 and Altstadt-Süd for the merger of the previous city districts 2 and 3.

history

Marienplatz is located in the center of the old town at the point where the traditional history of Munich began with the establishment of a market by Heinrich the Lion on June 14, 1158 in Augsburg's Schied . By the end of the 18th century, the history of Munich was essentially a history of the city (now the Old Town), the outside of Munich city fortifications located in Munich truce played contrast, a minor role. In 1255 Munich became the seat of the Wittelsbach family, 1506 the capital of the reunited Bavaria, 1806 the capital of the Kingdom of Bavaria . This role as a royal seat shaped the history and the cityscape of Munich's old town; the citizens were only able to emancipate themselves gradually from the ducal city rule. In the north of the old town, the Residenz , the Theatine Church and the National Theater dominate the cityscape. The New Town Hall on Marienplatz, the demonstration of urban independence, dates from the end of the 19th century.

The area of the old town was largely destroyed in the Second World War . The reconstruction was carried out while largely preserving the medieval streets and most of the large buildings that determine the cityscape, such as the churches, the residence , the national theater , the Old Court , the city gates, as far as they were still preserved before the war, as well as the Old and New Town Hall . Most of the bourgeois buildings in Munich's old town, as documented in the photographs by Georg Pettendorfer , have largely been lost. The main changes to the street scene were the evacuation of Marienhof and the breakthrough from Rindermarkt to the south, which created large squares instead of the original narrow streets. The construction of the Altstadtring in the 1960s brought about a further intervention in the building fabric and the character of the old town . Through the creation of a pedestrian zone in 1972, through traffic was completely removed from the old town.

Subdivision

A first subdivision of the city took place in 1271 through the division of the parish of St. Peter along the east-west axis of the city (the Salzstrasse) and the elevation of the Frauenkirche to the second parish church. Although the primary was a religious division, she also served in secular documents to designate the north or south half of the city and even outside the city truce as St. Mary and St. Peter.

In 1300 a subdivision into an inner and an outer city was first mentioned in a document. Inner City referred to the core city surrounded by the first city wall, which went back to the founding of Henry the Lion and was therefore often referred to as the Leonean city or Heinrich city in the history of Munich. Outer city referred to the city extensions under Ludwig the Strengen and Ludwig the Bavarian , which was surrounded by the 1300 still under construction second city wall. The boundary between the inner and outer city ran roughly along today's streets Sparkassenstrasse, Viktualienmarkt, Rosental, Färbergraben, Augustinerstrasse, Schäfflerstrasse, Schrammerstrasse and Hofgraben. This division had no administrative significance. There was a social gradient between the two areas, even if the inner city was not, as is sometimes shown, inhabited only by patricians. The division into inner and outer city was combined with the parish division. B. the southern half of the inner city "inner city Petri".

In the Middle Ages, more important than the distinction between inner and outer city was the still existing division of the old town into quarters, which were separated from each other by Munich's main traffic axes. The quarters are mentioned in writing for the first time in a document dated January 21, 1363 under Latin names: "quarta fori pecorum" (quarter of the cattle market, cattle market quarter) "quarta secunda ad gradus superioris institarum" (second quarter to the upper Kramen, Kramenviertel), " quarta tercia apud fratres heremitanos ”(third quarter for the hermit brothers, Eremitenviertel),“ quarta ultima apud Chunradum Wilbrechtum ”(last quarter for Konrad Wilbrecht, Wilbrechtsviertel). The valley was listed as a separate area and not assigned to the quarters. A council minutes of December 29, 1458 designated three of the quarters with their current names for the first time: the Hackenviertel, the Kreuzviertel and the Graggenauer Viertel. The first quarter was also called Rindermarktviertel, the name Angerviertel was first mentioned on September 15, 1508, but was only used in council minutes from 1530. The valley was now no longer a separate area, but divided into the neighboring quarters. The order in which the quarters were enumerated remained unchanged from 1363.

This division into quarters, which is typical of many medieval cities, was initially a military division, which was then extended to public order. The quarters were originally headed by two captains each, from 1403 by three, one each from the inner and outer councils and from the community. These captains were responsible for internal security (police, night watch, guarding the city walls and gates, fire brigade, order at markets and events such as horse races) and directed the military presence of the citizens of Munich. If necessary, the military contingent of a district was further subdivided in the field. B. 1410 called "eighth". Because of their importance for the police services, the quarters were also referred to as police districts in the 19th century.

After Munich was deconsolidated at the end of the 18th century, the names of the quarters were extended to include the city extensions outside the old city walls, which were called the outer Graggenauer, Anger, Hacken and Kreuzviertel. It was not until 1812 that these areas were given their own names and were referred to as suburbs: St. Anna-Vorstadt (today Lehel ), Isarvorstadt , Ludwigsvorstadt , Maxvorstadt and Schönfeldvorstadt (today part of Maxvorstadt).

When the urban area was divided into city districts , the medieval districts formed the districts 1 to 4. After the Second World War, the districts were given names that, with the exception of the Angerviertel, had no reference to the historical names. In 1954, the districts 1 and 4 were combined to form the district of Altstadt-Nord and districts 2 and 3 to form the district of Altstadt-Süd. In what is now the Altstadt-Lehel district , the quarters form four of six districts and again bear their historical names. Its outer borders are mainly formed by the old town ring and are therefore largely outside the medieval borders.

| Surname | location | East or west border | North or south border | Quarter 1363 | Name 1363 | District no. | Name 1947 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graggenau district | Northeast | Weinstrasse - Theatinerstrasse | Marienplatz - valley | 4th | Wilbrechtsviertel | 1 | Max-Joseph-Platz |

| Angerviertel | Southeast | Rosenstrasse - Sendlinger Strasse | Marienplatz valley | 1. | Rindermarktviertel | 2 | Angerviertel |

| Hackenviertel | southwest | Rosenstrasse – Sendlinger Strasse | Kaufingerstrasse - Neuhauser Strasse | 2. | Kramenviertel | 3 | Sendlinger Strasse |

| Kreuzviertel | northwest | Weinstrasse –Theatinerstrasse | Kaufingerstrasse – Neuhauser Strasse | 3. | Hermit quarter | 4th | City district |

Graggenau district

The name of the Graggenau district is derived from the Graggenau, a land name called 1325 "Grakkaw" and 1326/27 "Gragkenawe", which has its roots in the word krack , which means raven, crow. The Graggenau quarter was the only one that was named after its captain when it was first mentioned in a document as the "Wilbrechtsviertel". According to other captains, it was called "des Hansen Barts Viertel" in 1420/21, in 1433 "des Scharfzahns Viertel", and in 1439 again "des Wilbrechtsviertel". The other quarters were also temporarily named after their captains. Together with the Kreuzviertel, the Graggenau district formed the area of the women's parish in the Middle Ages and, from 1954, the district of Altstadt Nord.

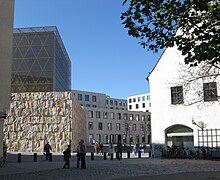

The Graggenau district is characterized by the ducal buildings of the Old Court and the Munich Residence , which together with the buildings between them and those assigned to court service, e.g. B. the old stables ( old mint ), the ducal armories and the Hofpfisterei , which divided the quarter into two halves, an area on the old town terrace and an area in the valley. The area north of Marienplatz was initially inhabited by the court servants and later also by wealthy citizens. The area in the valley was predominantly the seat of craft businesses. The Franciscan monastery at today's Max-Joseph-Platz , the Pütrich-Regelhaus (also: Pütrich-Seelhaus) and the Ridler-Seelhaus formed the spiritual focus of the district.

Bourgeois Munich has been represented in this quarter by the Old Town Hall since the Middle Ages . In the 19th century, the houses north of Marienplatz had to give way to the construction of the New Town Hall . Because of its proximity to the courtyard, the Graggenau district was particularly popular with travelers. Today the Platzl and the Hofbräuhaus are a tourist attraction. With Maximilianstraße , Residenzstraße and the east side of Theatinerstraße , the most elegant shopping streets are also located in this quarter. The Marienhof is located north of the New Town Hall . This area and its housing developments were destroyed by US bombing raids during World War II. In the meantime used as a parking lot, the Marienhof was never built on again. The green space there had to give way in 2018 as part of the construction work on the second S-Bahn trunk line.

Angerviertel

The Angerviertel takes its name from an anger , an open square that was originally located in the area of today's Sankt-Jakobs-Platz . It is the neighborhood that was last given its current name. The original name "Rindermarktviertel" came from the former cattle market, which the cattle market fountain by the sculptor Josef Henselmann from 1964 and the street name Rindermarkt still remember. According to captains of the quarter, it was referred to in 1420/21 as "the Hans Pütrich's quarter" and in 1445 as "the Rudolfs quarter". In 1487 the designation "am Anger ... zu München" is attested in a Munich notarial deed. Together with the Hackenviertel, the Angerviertel formed the area of St. Peter's Parish in the Middle Ages , but the area of the Heilig-Geist-Spital formed its own parish with the Heilig-Geist-Kirche as a parish church and its own cemetery. From 1954, the two quarters formed the Altstadt-Süd district.

The Angerviertel is shaped like a hook. In the middle is the Petersbergl on the old town terrace, to the east and south there is a narrow strip on the Hirschauterrasse, through which the city brooks flowed.

In the Angerviertel there were mainly traders and craftsmen who used the water power of the city streams for their businesses.

Hackenviertel

The Hackenviertel is named after a field name “in dem Haggen”, which was first mentioned in 1326 and which was in the area today bordered by the streets Altheimer Eck, Hotterstraße, Hackenstraße, Brunnstraße and Damenstiftstraße. This field name is derived from Hag , i.e. fenced in, fenced off area. In the Hackenviertel at the Altheimer Eck was the Altheim settlement , which was incorporated into the city area through its inclusion in the second city wall ring and is still noticeable today through the kinked course of the two east-west connections.

The origin of the original name "Kramenviertel" (quarter to the upper Kramen when it was first mentioned in 1363) is unclear, as the upper Kramen (general stores) were on the south side of Marienplatz, i.e. in the Angerviertel. He was probably talking about general stores on the south side of Kaufingerstrasse . According to captains of the quarter from the Schrenck family , it was referred to in 1420/21 as "the Lorenz Schrencken quarter" and in 1445 simply as "the Schrencken quarter". Together with the Angerviertel, the Hackenviertel formed the area of the St. Peter's Parish in the Middle Ages , the parish cemetery and the former cemetery church, today's All Saints Church on the Cross, were also located there . From 1954, the two quarters formed the Altstadt-Süd district.

In the Hackenviertel there were predominantly trading citizens. There were only a few aristocratic palaces there, and the convents of the Salesian Sisters (later St. Anne's Lady's Abbey ) and the Servite Sisters were not particularly noticeable due to their restrained architecture. Up until the Second World War, the two large complexes of the Herzogspital and the Josefspital shaped the appearance of the district.

Kreuzviertel

The Kreuzviertel got its name from Kreuzgasse, a street that today roughly corresponds to Promenadeplatz and Pacellistraße. The origin of the name is unclear, possibly it goes back to a former district mark or a field cross there. The original name "Eremitenviertel" refers to the monastery of the Augustinian hermits , which had been in this area since 1294 and of which only the secularized Augustinian church has survived. According to captains of the quarter, it was referred to in 1410 as "des Katzmairs quarter", in 1420/21 as "des Franz Tichtl's quarter" and in 1445 as "des Ligsalz quarter". Together with the Graggenau district, the Kreuzviertel formed the area of the women's parish in the Middle Ages , the parish cemetery and the former cemetery church, today's Salvatorkirche, were also located there . From 1954 the two quarters formed the city district Altstadt Nord.

In the Middle Ages, the Kreuzviertel was the center of the wealthy bourgeoisie. There, on the site of today's Promenadeplatz, stood the salt barn , where the salt was stored, to which Munich owed a large part of its prosperity. The houses of wealthy merchants and patricians were also located there. The most outstanding building of the Middle Ages is the Frauenkirche , which was elevated to Munich's second parish in 1271. A cemetery on the outer wall of the city with the Salvatorkirche as a cemetery church belonged to it.

From the 16th century, the bourgeois building fabric was pushed back more and more. First the large building complexes of the Wilhelmine fortress and the Jesuit monastery with the church of St. Michael and the old academy , today a meditation church, were built . This was followed by Carmelite and Carmelite monasteries and outside the city wall on a bastion of the ramparts the Capuchin monastery , so that the Kreuzviertel developed into a spiritual center.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, more and more aristocrats acquired land in the Kreuzviertel and built representative palaces, especially in the area of Promenadeplatz, Prannerstrasse and Kardinal-Faulhaber-Strasse. At the northern end of the Hinteren Schwabinger Gasse (today Theatinerstraße), the Theatinerkirche was built as a court church and the adjoining Theatiner monastery .

In the 19th century, state organizations were concentrated in this quarter, e. B. the state parliament in Prannerstraße, the interior ministry in the buildings of the Theatine monastery, which was dissolved during the secularization , and the foreign ministry with the seat of the prime minister in the Palais Montgelas . At the end of the 19th century, several banks took over old aristocratic palaces and erected monumental bank buildings in their place, e.g. B. the Königliche Filialbank (from 1918 Bayerische Staatsbank ) Kardinal-Faulhaber-Straße 1 , the Bayerische Hypotheken- und Wechsel-Bank Kardinal-Faulhaber-Straße 10 and the Bayerische Vereinsbank Kardinal-Faulhaber-Straße 14 .

See also

literature

- Carmen M. Enss: Munich's planned old town. Urban development and preservation of monuments from 1944 for reconstruction . Franz Schiermeier Verlag, Munich July 2016. ISBN 978-3-943866-46-9 .

- Klaus Gallas : Munich. From the Guelph foundation of Henry the Lion to the present: art, culture, history . DuMont, Cologne 1979, ISBN 3-7701-1094-3 (DuMont documents: DuMont art travel guide).

- Eva Graf: The city photographer . Georg Pettendorfers Views of Munich 1895–1935; The city center. Ed .: Richard Bauer . Heinrich Hugendubel Verlag, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-88034-447-7 .

- Heinrich Habel, Johannes Hallinger, Timm Weski: State capital Munich - center (= Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation [Hrsg.]: Monuments in Bavaria . Volume I.2 / 1 ). Karl M. Lipp Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-87490-586-2 .

-

Helmuth Stahleder ; Richard Bauer , Munich City Archives (ed.): Chronicle of the City of Munich . Dölling and Galitz Verlag , Munich 2005

- Volume 1: Duke and bourgeois town. The years 1157–1505 , ISBN 978-3-937904-10-8 .

- Volume 2: Burdens and pressures. The years 1506–1705 , ISBN 978-3-937904-11-5 .

- Volume 3: Forced Shine. The years 1706–1818 , ISBN 978-3-937904-12-2 .

- Helmuth Stahleder : House and street names in Munich's old town . Hugendubel, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-88034-640-2 .

- Helmuth Stahleder: From Allach to Zamilapark. Names and basic historical data on the history of Munich and its incorporated suburbs. Edited by Munich City Archives . Buchendorfer Verlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-934036-46-5 .

- Petra Wucher, Tobias Lill: Munich's new old town . local national international. MünchenVerlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-937090-38-2 .

- Elfi Zuber (Ed.): The Graggenauer Viertel . Institut Bavaricum Munich Elfi Zuber, Munich 1989.

- Elfi Zuber (Ed.): The Kreuzviertel . Institut Bavaricum Munich Elfi Zuber, Munich 1987.

- Elfi Zuber (Ed.): The Hackenviertel . 2nd revised edition. Institut Bavaricum Munich Elfi Zuber, Munich 1986.

- Elfi Zuber (Ed.): The Angerviertel . Institut Bavaricum Munich Elfi Zuber, Munich 1991.

Web links

- Old town district in the city portal www.muenchen.de

- Graggenauviertel in the city portal www.muenchen.de

- Angerviertel in the city portal www.muenchen.de

- Hackenviertel in the city portal www.muenchen.de

- Kreuzviertel in the city portal www.muenchen.de

Individual evidence

- ^ Ensemble Altstadt München at the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation

- ↑ Bodendenkmal Altstadt Munich at the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation

- ↑ Christian Müller: Munich under King Maximilian Joseph I. Google Books, 1816, p. 87 , accessed on October 27, 2010 .

- ↑ Stahleder: From Allach to Zamilapark , p. 18f

- ↑ Stahleder: Chronicle. Volume 1, p. 39.

- ↑ Stahleder: Chronicle. Volume 1, p. 133.

- ↑ 2.stammstrecke-muenchen.de: Construction of the noise protection wall for the construction site at Marienhof has started

- ^ Hannes Obermair : Bozen Süd - Bolzano Nord. Written form and documentary tradition of the city of Bozen up to 1500 . tape 2 . City of Bozen, Bozen 2008, ISBN 978-88-901870-1-8 , p. 193, no.1322 .

Coordinates: 48 ° 8 ′ 14 " N , 11 ° 34 ′ 31.3" E