Munich city fortifications

The Munich city fortifications were a system of several city walls , ditches and bastions that surrounded the city of Munich in the course of its history . As early as the 12th century, a curtain wall with an upstream moat was laid around the still young settlement.

When this ring became too narrow, the first expansion of the city towards the Isar into the valley followed in the early 13th century, which was presumably only fortified with a moat wall system, and then one in the late 13th to the 14th century second extension in all directions and the construction of a second curtain wall with a moat. This wall was reinforced by a fence wall at the beginning of the 15th century . A wall fortification was built around this double wall ring in the 17th century .

At the end of the 18th century, Munich's status as a fortress was lifted and the demolition of the fortifications began. In the 19th century, the city wall with its gates and towers was largely demolished. Today only a few remains of the city fortifications have survived, including three of the original four main gates of the second city wall.

history

First city wall

Soon after the city of Munich was founded by Heinrich the Lion , the city was fortified, probably at first only by an earth wall with a ditch in front. Towards the end of the 12th century, this fortification was replaced by a city wall, in front of which a water-filled moat was dug. It is unclear whether this wall was already started under Henry the Lion or under his Wittelsbach successors. For example, some historians interpret an Ortolf "qui praeest muro" (who protrudes from the wall) mentioned in 1175 as the head of the construction of the city wall, while others refer the wall to the castle wall of the Old Court , the first palace of the Bavarian dukes in Munich.

The first city wall was about 1400 m long, the area enclosed by it was about 17 hectares. The course of the wall can still be seen in today's street scene from the course of the following streets: Sparkassenstraße, Viktualienmarkt, Rosental, Färbergraben, Augustinerstraße, Schäfflerstraße , Marienhof, Hofgraben, Pfisterstraße (up to Sparkassenstraße). The irregular course of the city wall resulted from the fact that the original city was located on the edge of a terrace, which was later referred to as the old town terrace because of the city's foundation on this terrace and on the east side of which the terrain sloped a few meters towards the Hirschauterrasse. That is why the city wall ran there in a straight line along the edge of the slope, while it itself followed an arch on the old town terrace.

The wall was about 1.70 to 2.00 m thick and was probably about 5–6 m high. It was designed as a two-shell brick wall that was filled with gravel and poured with mortar. Instead of a deep foundation, the wall almost always stood on a flat gravel and mortar base.

The moat ran at a distance of about 10 to 15 m in front of the city wall and was fed by the Großer Angerbach , which flowed roughly along today's Oberanger and turned off the city wall to the east into the Rosental. At the corner of Rosental / Viktualienmarkt, it merged with the Roßschwemmbach to form the Pfisterbach and flowed north in the city moat along the edge of the slope. Since the other part of the city wall ran on top of the old town terrace, a 5 m deep trench had to be dug in order to have at least 2 m water depth and the necessary gradient to branch off part of the Großer Angerbach to the west and to divert it around the city wall. At the northern end of today's Sparkassenstrasse, this stream, first called Färbergrabenbach and then Hofgrabenbach , flowed back into the Pfisterbach.

The first city wall had five gates:

- the rear Schwabinger Tor (Wilbrechts- / Scheffler- / Tömlinger- / Nudelturm) in the northwest (at the end of the Weinstrasse)

- the Vordere Schwabinger Tor (Krümleins- / Muggenthaler- / La-Rossee- / Police Tower) in the northeast (at the end of Dienerstraße)

- the Talburgtor (lower gate, Talbruckor, town hall tower) in the east (next to the old town hall )

- the Inner Sendlinger Tor (Pütrich- / Blauenten- / Ruffini tower) in the south (at the end of Rosenstrasse)

- the Kaufingertor (Upper Gate, Chufringer Gate, Beautiful Tower) to the west (at the end of Kaufingerstrasse)

Occasionally the designation Inneres Schwabinger Tor is used, but it is ambiguous and is sometimes related to the Rear Schwabinger Tor and sometimes to the Front Schwabinger Tor.

These gates were built as multi-storey towers with a gate passage . The floor area was about 5 × 5 m, the masonry was, like the city wall, a two-shell brick wall with a gravel and mortar filling.

It is not known whether the first city wall had other towers for observation and defense in addition to these gate towers. Contrary to earlier assumptions, the lion tower , which is still standing today, was not a defensive tower of this city wall, but was built directly above the city moat and was probably used to regulate the water levels of the city moat through weirs.

City expansion into the valley

The space within the first city wall soon became too narrow. As early as the beginning of the 13th century, Duke Ludwig I saw the first expansion of the urban area into the valley as far as the Kaltenbach , which was later called Katzenbach and ran roughly along the line Hochbrückenstraße-Radlsteg. Part of this city expansion was the Heilig-Geist-Spital , built in 1208 east of the Peterskirche outside the city wall .

As a result of the expansion, the urban area was enlarged to around 26 ha. However, the area in front of the first city wall was probably not surrounded by a solid wall, but by a rampart moat. The Kaltenbachtor at the later high bridge , where the Salzstrasse crossed the Kaltenbach, provided access to the delimited area as the Vorwerk of the Talburgtor. Tolls and customs were still only collected at the Talburgtor. Presumably the Rosenturm at the transition between Rosental and Viktualienmarkt and the Graggenauer Tor, the later Wurzer or Kosttor , were already the city gates of this first city expansion.

Second city wall

After Ludwig the Strict moved his residence to Munich as Duke of Upper Bavaria after the first division of Bavaria in 1255 , the population continued to grow rapidly. Ludwig therefore began to expand the city again, this time in all directions. To protect the new areas, the construction of a second wall ring began in 1285, but was only completed under Ludwig IV with the completion of the Isartor in 1337 and with it the inclusion of the Talvorstadt (formerly called Gries = gravel bank) in the fortified urban area. 1478–1499 the area enclosed by the city wall was expanded to include the area between Marstallplatz and Marstallstraße.

The second city wall was about 4000 m long, the area enclosed by it had an area of about 91 hectares, more than five times the original city area. On the old town terrace, the wall ran in an arc about 400 m from the first city wall, on the Hirschauterrasse it protruded like a nose to the east towards the Isar. From Schwabinger Tor, the northern city gate, the wall ran roughly along today's streets Hofgartenstraße, Marstallplatz, Falkenturmstraße (from the end of the 15th century Hofgartenstraße, Marstallstraße), Am Kosttor, Neuturmstraße, Marienstraße, Lueg ins Land, Isartor, Westenrieder Straße, Viktualienmarkt , Blumenstrasse, An der Hauptfeuerwache, Herzog-Wilhelm-Strasse, Herzog-Max-Strasse, Maxburg, northern part of Rochusstrasse, Rochusberg, Jungfernturmstrasse and then directly north past the Theatinerkirche back to Schwabinger Tor.

At Marstallplatz and in Blumenstrasse the second wall was an extension of the straight stretch of the first wall. At Marstallplatz it ran like the first wall along the edge of the slope, but on Blumenstrasse the edge of the slope dodged to the west, so that there was also an area on the lower Hirschauterrase included in the walled city area, the so-called Anger with the Great and Small Angerbach . The area between Talburgtor and Isartor (the Talvorstadt) was also on the Hirschauterrasse and was traversed by several of Munich's city streams . In the Rose Valley, the two rings of the wall came very close, only the Rose Tower stood here as a passage between the second city wall and the houses that had been built along the moat of the first wall.

The former village of Altheim , a settlement that probably existed before Munich was founded, was also included in the new urban area. The district within the first ring of the wall was referred to as the inner city , the area between the first and second ring of the wall as the outer city . After the completion of the second city wall, the first city wall was no longer used for defensive purposes. Wherever they have changed traffic routing or new buildings such as B. stood in the way of the Frauenkirche , it was demolished, otherwise it was integrated into newly built houses. The water-filled city moat was used like the other city streams for the supply of service water and sewage disposal.

The second city wall was about 2 m wide on the old town terrace, in its eastern part on the Hirschauterrasse only about 1.50 m and had a height of about 8-10 m. It was built on a foundation of tufa blocks and stood on a 1 m high earth wall. Like the first city wall, the second was also a double wall made of bricks with a gravel and mortar filling. On the inside of the wall, a wooden battlement ran around the city.

The second city wall was also surrounded by a moat filled with water. However, nothing of this has survived today, as a fence wall was later built on the site of this ditch. There were four main gates in this second city wall. Since Theatinerstrasse and Residenzstrasse converge at their northern end, only one city gate was required in the north. The main gates were:

- the Schwabing Gate in the north at the end of Theatiner- and Residenzstraße

- the Isartor in the east at the end of the street Tal

- the Sendlinger Tor in the south at the end of Sendlinger Straße

- the Neuhauser Tor (called Karlstor from 1791) at the end of Neuhauser Straße .

Like those of the first city wall, these gates initially consisted of a multi-storey gate tower, which is only preserved at the Isartor today. Their later appearance with the front gate flanked by two side towers was not given until the beginning of the 15th century with the construction of the kennel wall. In contrast to the first city wall, the gate towers did not have a square, but a rectangular floor plan and were about twice as wide as they were deep. Above the gate passage there was a guide shaft for a portcullis made of about 10-15 cm thick wooden poles.

In addition to the four main gates, there were also smaller city gates:

- the Wurzertor , later called the Kosttor, because feeding the poor was set up here

- the Taeckentor , which had been walled up since around 1400

- the ship's gate , later called the inlet gate, because admission was granted here at night for a fee when all other gates were locked

- the Angertor , which offered access to the lower Anger and which was often closed because of its low traffic importance

Two further gates did not serve to access the city, but to connect the ducal residences directly to the outside:

- the Neuvesttor , which led directly out of the city from the Neuveste , which was formerly located in the northeast corner of today's residence

- the Herzogenstadttor , through which a path led from the Wilhelminian Veste to the Capuchin monastery outside the city (later on a bastion of the fortress wall)

Between the gates, numerous towers were used to observe the surrounding area and defend the wall. The towers of the second city wall were all square towers built as shell towers , i.e. open to the city side. After being captured by attackers, they could not be defended towards the city. The exact number of towers of the second city wall is unknown. In Sandtner's city model there are 55 towers, but the number is different for different cityscapes, and the numbers also fluctuate in documents of the city. A maximum of 63 towers are mentioned. Most of these towers did not have a name, or at least this is not known. However, some towers that had a special meaning or served a specific purpose are known by name. These were mostly higher than the others and also had a wall on the city side. Below are

- of Christoph Sturm , formerly a city wall tower in the northeast corner of the wall, and later in the Neuveste integrated

- the falcon tower between the Altes Hof and Neuveste, in which utensils for falconry were temporarily stored and which later served as a prison

- the fishing tower at today's Viktualienmarkt

- the witch tower , a neighboring tower of the falcon tower, which was also used as a prison

- the Heyturm , under which the Glockenbach entered the city and divided there into the large and small Angerbach, the tower served as a water tower

- the Katzenturm above the influence of the Katzenbach in the city, which was used as a water tower from 1615

- the Lueg ins Land or Lugerturm just north of the Isartor, which was used to monitor Munich's apron in the valley.

- the miller tower

- the pocket tower

- the Tuchschererturm

- the tower at Saint Sebastian

The little fist turret between Sendlinger Tor and Heyturm was unique and rested on the inside of the wall as a small round turret with a stone conical roof on a pillar.

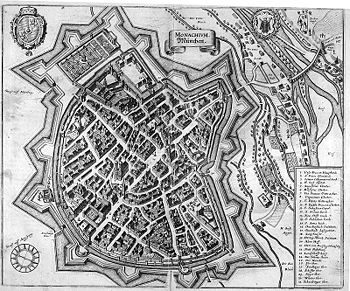

Kennel wall

Because of the Hussite Wars that broke out at the beginning of the 15th century , the second city wall was reinforced with a kennel from 1424 . For this purpose, the original moat was filled in and instead a kennel wall was built parallel to the original wall. New moats were then dug in front of this wall. These building measures are documented in writing from 1430 onwards. They lasted until 1472. The kennel complex is clearly visible in the oldest city maps of Munich by Tobias Volckmer (1613) and Matthäus Merian (1642) and in the city model of Munich by Jakob Sandtner (1570). The oldest view of Munich by Michael Wolgemut in Schedel's world chronicle (1493) also clearly shows the double wall.

The Zwingermauer ran parallel to the second city wall at a distance of 7–9 m and stood on a foundation made of Nagelfluh . It was also built as a two-shell infill wall. With a height of about 5 m it was only half as high as the city wall, its width at the top of the wall was about 1 m. This comparatively small thickness of the wall was compensated by the fact that the kennel between the city wall and the kennel wall was piled up to 2 m high with earth and rubble, which gave the kennel wall sufficient strength at its base.

The moat ran around the kennel wall at a distance of about 3–4 m. Its depth was about 4 m, in some places it was up to 30 m wide. The moat was fed by the Glockenbach , which was routed between dams through the moat in front of the Zwingermauer. Weirs in the dams regulated the outflow of water to the west and east into the Westliche Stadtgrabenbach and the Ostliche Stadtgrabenbach , which flowed to the north in the city moats in front of the Zwingermauer around the old town.

With the construction of the kennel wall, the gates were also strengthened. The four main gates and the Angertor received front gates, which consisted of a piece of wall with a gate passage and two flanking towers. These towers were square at Schwabinger and Neuhauser Tor, hexagonal at Sendlinger Tor, octagonal at Isartor and semicircular shell towers at Angertor. At the side, the space between the front gate and the gate tower was bounded by further walls, so that attackers who had taken the front gate found themselves in a walled courtyard that could be shot at from all sides. Only at the Isartor is this facility still preserved or rebuilt today.

There were also numerous towers in the kennel wall between the gates. Sandtner's city model shows 44 towers, but as with the second city wall, the number varies in the documents. As with the city wall, most of the towers were open shell towers on the city side. In contrast to the city wall, there were not only square but also round towers on the Zwingermauer. Of particular importance were:

- the maiden tower, the old tower of the second city wall, was expanded into a strong bastion tower, which took up the entire area between the city wall and the kennel wall and protruded semicircularly from the kennel wall;

- the new tower, a round gun turret at the Kosttor;

- the Scheibling at the Isartor, called Prinzessturm from the 19th century , a round gun turret at the Lueg into Land;

- the Scheibling at the Schiffertor , a round gun tower in front of the Fischerturm on today's Viktualienmarkt , next to which the Roßschwemmbach flowed under the Zwinger wall into the Zwinger.

At the end of the 15th century, Vorwerke in the form of semicircular barbican were built in front of the Schwabinger, Neuhauser and Sendlinger Tor . Its straight back stood at the city moat, and a water-filled moat ran around its semicircular front. The barbican in front of the Schwabinger and Neuhauser Tor were bricked, they were built around 1493. The barbican in front of the Sendlinger Tor, which was probably built later, was an earthwork with a sloping embankment, only the back wall to the moat was bricked. The paths led from the city gates over the city moat and made a bend on the barbican. They were then led across the barbican moat parallel to the city wall. At the barbican in front of Sendlinger Tor, the path led through the powder tower , which served as a gate tower.

Initially, the Laimtor shortly before the Isartor served as the entrance to the Isartor. 1517–1519 the Red Tower was built on the bridgehead of the Isar Bridge .

Wall fastening

With the advent of heavy artillery , the city walls were no longer able to cope with the military requirements. A first draft to surround Munich with a fortress ring dates from 1583. He envisaged a regular octagon around the city that extended to the Isar, and on the other bank of the Isar on the Gasteig a pentagonal fort , as there was a danger The bombardment of Munich was greatest from there. However, this and other competing plans were not implemented, and the designers of the plans accused each other of serious defects in their plans. It was only after the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War that Elector Maximilian I pushed the plans and, from 1619, had a fortress belt with bastions built around the existing city wall. This fortress belt essentially followed the course of the medieval city wall, only in the north was the area of the court garden and to the east of the residence the Marstallplatz with the armories located there included in the fortress.

In a first construction phase, the northern part of the wall fortification between Schwabinger Tor and Kosttor was built from 1619 to 1632. When King Gustav Adolf II of Sweden moved into Munich in 1632, this part of the fortifications was completed. Due to the payments to be made to Gustav Adolf and a plague epidemic, the expansion progressed only slowly in the following years. In 1637 Maximilian I achieved the financial participation of the whole country in the fortress construction in Munich by levying a special tax. So the work could be carried out more intensively from 1638 onwards. The ring around the city was probably closed in 1640. This year Maximilian had a coin of five ducats minted , on the reverse of which the city of Munich surrounded by the ramparts is depicted. However, work continued on the fortification, on the one hand to reinforce weak points and widen the trenches, on the other hand to maintain the wall and repair any damage that had occurred. So the construction work went seamlessly into the maintenance work, which makes it impossible to give an exact date for the completion of the fortress.

The fortress ring was not bricked, but built according to the Dutch construction method as an earth wall, in front of which there was a wide moat. The main wall with parapet was about 8 m high and had a slope angle of about 45 °. The embankment was paved with pieces of lawn. A total of 18 bastions protruded from the wall, but only five ravelins (mainly on the east side) were in front of the curtains in the moat. So were z. B. the paths through the Kosttor, the Isartor and the Neuhauser Tor over Ravelins to the other side of the trench. The trench was about 15 to 30 m wide. In the eastern part, which was on the Hirschauterrasse, the ditch could be flooded by the city streams, but it did not always carry water. Not only were the inner city streams used, as was the case with the moat of the city wall , but the Stadthammerschmiedbach (originally Laimbach ), which flowed past the city east of the Isar Gate, was also used to water the moat.

The northern part between Schwabinger Tor and Kosttor was the most developed. Here was another front of the main Wall Niederwall . A battlement ( berm ), which was protected by palisades , ran in the lower part of the embankment of the main wall. A covered path ran on the outside of the trench , which was protected by the rising glacis . The Niederwall was missing in the rest of the fortress ring. The battlements ran at the foot of the main rampart, and the palisades stood directly on the moat.

The new fortress ring never had to prove its suitability for war. As early as the end of the 17th century, parts of the fortress were transferred to private owners. They were allowed to use the site, but had to maintain the wall. De facto, however, the suitability for warfare of the facility steadily decreased until it was razed at the end of the 18th century.

Softening of Munich

In 1791, Elector Karl Theodor ordered the bastion in front of the Neuhauser Tor to be razed and the access to the gate to be redesigned. In 1795 he finally revoked Munich's status as a fortress. At the end of the 18th century, the fortress ring from the 17th century was demolished, and in the 19th century the second city wall with its castle wall and most of the towers and gates were torn down. Only the Isartor and the front gates of the Sendlinger Tor and the Karlstor have been preserved. King Ludwig I personally campaigned for the preservation of the Isartor . He also had the already demolished courtyard between the gate tower and the front gate restored.

Todays situation

Preserved parts of the city fortifications

Only a few fragments of the first city wall have survived that were included in the construction of houses, especially in Burgstrasse 2 to 12 and in Rindermarkt 6. The rear Schwabinger Tor was torn down in 1691, most of the remaining gate towers were in Demolished 19th century. Only the Talburgtor remained as a town hall tower. After severe destruction in World War II , it was torn down and rebuilt based on the historical model.

A short section of the second city wall on Jungfernturmstrasse with the south wall of the Jungfernturm facing the city has been preserved. During construction work north of the Isartor, further remains of the second city wall were exposed from 1984 onwards. They may have disappeared underground again today, but the course of the wall between Isartor and Lueg into the country is made clear by red stones in the pavement. A short section of the wall still runs above ground, but is covered with new bricks for protection.

Part of the north wall of the Lueg ins Land is now integrated into the Vindelikerhaus , with the original inside of the tower wall now forming the outer facade. A loopholes can still be seen on the facade. The layout of the Lueg ins Land is also marked with red stones in the pavement. Of the gate towers of the second city wall, only the gate tower of the Isar gate is preserved today.

Only a few remains of the kennel wall are preserved north of the Isar gate. They are partially exposed in the business premises in the basement at Thomas-Wimmer-Ring 1 and can be viewed from the outside like an archaeological window . In an inner courtyard at Thomas-Wimmer-Ring 1a, further remains of the Zwingermauer and the foundation walls of the Prinzessturm can be seen. During archaeological excavations in the run-up to construction work in February 2011, the foundations of the Zwinger Wall and a half-shell tower were uncovered on the site of the former synagogue on Westenriederstrasse . They were recovered and partly rebuilt in the green strip between Westenriederstrasse and Frauenstrasse southwest of the Isartor. The front gates of Neuhauser Tor (today Karlstor), Sendlinger Tor and Isartor are almost completely preserved or rebuilt.

Only one bastion in the financial garden remains of Munich's wall fortification , which was called the “garden bastion” because of its location in front of the courtyard garden, and the curtain wall to the west, but it is heavily sanded down due to its character as an earthwork.

During the construction of the Stachus basement in 1968, a remnant of the barbican in front of the Karlstor was exposed, as well as an escape tunnel in the direction of Bayerstraße. A small part of this tunnel can be seen today in the Brunnenhof in the middle of the 1st Stachus basement.

Memorial plaques

In various places, memorial plaques, reliefs or other reminders of the former city fortifications. However, historical data and facts (e.g. construction time and appearance) are often not correctly reproduced.

| place | Art | reminds of |

|---|---|---|

| At inlet 1 | Stone tablet | Outer inlet gate |

| Kaufingerstraße 28, Hirmer office building | Pavement | Floor plan of the Kaufingertor |

| Kaufingerstraße 28, Hirmer office building | Bronze plaque | Kaufingertor |

| Kaufingerstraße 28, Hirmer office building | House plastic | Kaufingertor |

| Jungfernturmstrasse | Stone tablet | Maiden Tower |

| Lueg into the country | Pavement | Course of the second city wall and floor plan of the Lueg into the country |

| Marienstraße 21, Vindelikerhaus | Wall painting and stone tablet | Lueg into the country |

| Prälat-Zistl-Strasse 4 | Stone tablet | Inlet gate |

| Rindermarkt 10, Ruffinihaus | Wall painting | Inner Sendlinger Tor , also called Ruffini Tower |

| Thomas-Wimmer-Ring 1 | Display board | Situation between Isartor and Lueg in the country |

| Westenriederstrasse 20 | Stone tablet | Tower of the Zwing Wall |

Street names

Some street and square names that are derived from the fortifications are also reminiscent of the former city fortifications. Färbergaben and Hofgraben are named after the first fortification, after the second the Jungfernturmstrasse, Falkenturmstrasse, Neuturmstrasse, Am Kosttor, Lueg ins Land and Zwingerstrasse (although the road was not in the Zwinger, but only led to it), after the fortifications Wallstrasse (which was laid out on and on the former wall).

To this day, the streets inside the first fortification have different names from their continuations outside. So z. B. the Weinstrasse at the point where the former Wilbrechtsturm (the rear Schwabinger Tor) stood, into Theatinerstrasse. It is also at Dienerstraße - Residenzstraße am Krümleinsturm (front Schwabinger Tor), Marienplatz - Tal am Rathausturm (Talburgtor), Rosenstraße - Sendlinger Straße am Ruffiniturm (Inner Sendlinger Tor) and Kaufingerstraße - Neuhauser Straße am Schönen Turm (Kaufingertor).

literature

- Christian Behrer: The subterranean Munich - city core archeology in the Bavarian capital . Buchendorfer Verlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-934036-40-6 , chap. 4.3: City fortifications , p. 110-162 .

- Christian Behrer: Ground monument preservation in Munich . In: Landeshauptstadt München Mitte (= Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation [Hrsg.]: Monuments in Bavaria . Volume I.2 / 1 ). Karl M. Lipp Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-87490-586-2 , p. XLIII-LVII .

- Walther Betz: The wall fortification of Munich . In: Michael Schattenhofer (Ed.): New series of publications by the Munich City Archives . tape 9 . Munich City Archives, Munich 1960 (with attached map).

- Brigitte Huber: walls, gates, bastions. Munich and its fortifications. Ed .: Historical Association of Upper Bavaria. Volk Verlag, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-86222-182-0 .

- Christine Rädlinger : History of the Munich city streams . Published by the Munich City Archives . Verlag Franz Schiermeier, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-9809147-2-0 .

-

Helmuth Stahleder : Chronicle of the City of Munich . Edited for the Munich City Archives by Richard Bauer. Dölling and Galitz Verlag , Ebenhausen / Hamburg 2005.

- Volume 1: Ducal and Citizens' Town: The years 1157–1505 . ISBN 978-3-937904-10-8

- Volume 2: Burdens and Oppressions: The Years 1506–1705 . ISBN 978-3-937904-11-5

- Volume 3: Forced Gloss: The Years 1706–1818 . ISBN 978-3-937904-12-2

- Helmuth Stahleder: House and street names in Munich's old town . Hugendubel, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-88034-640-2 , chapter gates and towers , p. 539-665 .

- Michael Weithmann: Castles in Munich . Stiebner Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8307-1036-4 , chapter The solid city of Munich , p. 99-148 .

- Otto Aufleger, Karl Trautmann: Old Munich in words and pictures . Published by Aufleger and Trautmann. Publishing house L. Werner, Munich 1897.

- Hans Lehmbruch: A New Munich - Urban Planning and Urban Development around 1800 . Ed .: Historical Association of Upper Bavaria. Buchendorfer, Munich 1987, chapter The dissolution of the Munich city fortifications .

Web links

supporting documents

- ↑ Christian Behrer: The lion tower in the middle of Munich . In: City of Munich, Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation (Ed.): The Lion Tower in Munich . Karl M. Lipp Verlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-87490-739-2 , p. 15-25 .

- ↑ Stahleder, Chronik, Vol. 3, p. 407.

- ↑ Stahleder, Chronik, Vol. 3, p. 440.

- ↑ Martin Bernstein: Risen from the pit. In: sueddeutsche.de. Süddeutsche Zeitung , February 9, 2011, accessed on April 27, 2015 .