Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| J84.1 | Other interstitial lung diseases |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

A : alveoli

AS : alveolar septa

BR : bronchioli respiratorii

BT : bronchiolus terminalis

D : mucosal

gland DA : ductus alveolaris

M : circular muscle layer of the bronchiolus

N : nerve

PA : branches of the pulmonary artery

PV : branches of the pulmonary veins

The idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) form a group of rare forms of disease caused by varying degrees of lung inflammation ( pneumonia ) and scarring ( pulmonary fibrosis ), mainly the connective tissue of the lung ( the interstitium ) are indicated. They differ in terms of the signs of the disease ( symptoms ), the findings mainly from imaging tests , the pathology , the course of the disease and the treatment options. The cause of the development of these clinical pictures is not known - they are therefore referred to as " idiopathic ". The IIP belong to the large group of interstitial lung disease (English: I nterstitial L ung D isease or ILD), in which more than 200 separate medical conditions classified be. The main symptom of interstitial lung diseases is shortness of breath (dyspnoea). All forms of IIP lead to pneumonia of varying severity, which primarily affects the connective tissue (interstitium) of the lungs . In addition, there may be scarring of the lungs called pulmonary fibrosis. In some forms, pulmonary fibrosis is in the foreground and the inflammation is only an accompanying reaction. The prognosis or the course of the disease and the treatment options depend, among other things, on the importance of the inflammation or fibrosis in the respective form of the disease.

classification

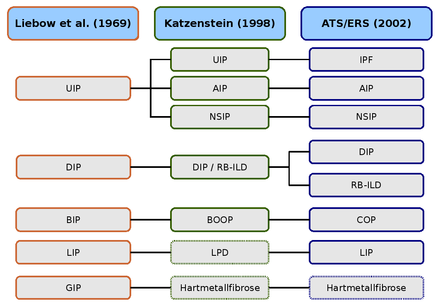

The current classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) is based on a guideline jointly published by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) in 2002. According to this classification, seven forms of disease are distinguished, each of which is defined by different clinical, radiological and pathological criteria. In addition, a category for non-classifiable IIPs has been introduced, to which all cases are assigned that cannot be clearly delimited:

- idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis) ,

- non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) ,

- cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) ,

- acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) ,

- respiratory bronchiolitis with interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD) ,

- desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) and

- lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) .

The importance of the new classification lies primarily in the cross-disciplinary (interdisciplinary) definition of the various forms, which pathologists , radiologists and internists made largely independently of one another in previous publications . It was made clear that the histopathological pattern must be distinguished from the clinical diagnosis. A reliable clinical diagnosis is based on clinical, radiological, and histopathological findings. Although the level of evidence of the classification is low, as it is based on the findings of experts, it forms the basis for future studies, as there are now uniform criteria in this area.

Epidemiology

The epidemiological data on idiopathic interstitial pneumonia are not very reliable. American work on the superordinate group of all interstitial lung diseases (ILD) was carried out in New Mexico, among others. According to this study, the prevalence of ILD is 80 cases per 100,000 population in men and 67 cases per 100,000 population in women. A diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) makes up about 45 percent of all cases of ILD.

According to this study, the prevalence of IPF is 20 cases per 100,000 population in men and 13 cases per 100,000 population in women. As this study was carried out before the new classification was published, the validity of this information is questionable. A more recent study assumes a higher prevalence. There is evidence that the IPF is increasing in western countries. The epidemiology of the other forms of IIP is even less well researched.

Anatomical basics

PB : peribronchial connective tissue, BT : terminal bronchiolus, M : circular muscle layer of the bronchiolus, P : branch of the pulmonary artery, DA : ductus alveolares, A : alveoli, AS : alveolar septa.

Staining with hematoxylin-eosin (HE).

The interstitium (interstitial tissue) of the lung is in the form of so-called Interalveolarsepten between the walls of the air sacs (alveoli). The latter represent the actual functional lung tissue ( parenchyma ) because the gas exchange between blood and air takes place in them . However, the interstitium and parenchyma work closely together in lung mechanics and form a functional unit. The interstitium is the basic structure of the lungs and maintains the architecture of the alveoli and thus the blood-air barrier during the respiratory cycle. The connective tissue portion of the interalveolar septa consists of cells, especially the connective tissue formers ( fibroblasts ), the structural proteins they form and substances such as collagen , elastic fibers , proteoglycans and other glycoproteins .

The main part of the interstitium is made up of collagen fibers, which make up up to 20 percent of the dry lung mass. In the interstitium of the lungs, type I collagen is predominant, which is believed to play the main role in maintaining the shape and elasticity of the alveoli. Type IV is only present in the basement membranes of the alveoli and blood vessels. Type III and V collagen is only formed to a small extent (5 to 10 percent) in the lung tissue. The elastic fibers form a branched network in the interstitium of the lungs. They are the driving force of exhalation ( expiration ).

Proteoglycans form the basic substance of the interstitium, they ensure that the spatial structure of the lung tissue is maintained. Its precise role in lung function is not known in detail. Hyaluronic acid , chondroitin sulfate A and C , dermatan sulfate , heparin and heparin sulfate are found in the lungs . Other glycoproteins include fibronectin and laminin , which are mainly found in the basement membranes.

Pathogenesis

As pathogenesis mechanisms are referred to contribute to the emergence of disease. In idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP), inflammation and fibrosis of the lung tissue play a decisive role. They have a different status with the different forms. However, the pathogenesis is not fully understood.

inflammation

In most interstitial lung diseases and most forms of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, the inflammatory response appears to play the decisive role in the pathogenesis. A microscopic examination reveals large accumulations of inflammatory cells ( macrophages , granulocytes, and lymphocytes ) in the lung tissue of these diseases, especially in the early stages . Fibrosis areas occur only to a small extent and only rarely does end-stage lung fibrosis develop. The pulmonary fibrosis is then a consequence of the inflammatory reaction. This theory is reinforced by the fact that the diseases respond well to anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapies. Eliminating the inflammation that is causing the pulmonary fibrosis can prevent further progression.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and probably also acute interstitial pneumonia occupy a special position. The hypothesis that an inflammatory reaction is the condition for the development of pulmonary fibrosis does not seem to be sustainable here. The inflammatory reaction obviously plays a subordinate role here or is only an accompanying reaction to pulmonary fibrosis.

Pulmonary fibrosis

The pulmonary fibrosis is a reaction in which it comes to the scarring of lung tissue. Different cell types play an important role in the development of pulmonary fibrosis. As far as we know today, the most important are fibroblasts, endothelial cells and alveolar epithelial cells . After damage to the lung tissue, the cause of which is unknown in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, the fibroblasts either first become inflamed and then activate, or they are activated directly, i.e. without prior inflammation. This depends on which model is used. The activation of the fibroblasts is initiated by various messenger substances, for example growth factors such as transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) and various interleukins that are released from other cells and the fibroblasts themselves. This leads to cell multiplication ( proliferation ) of the fibroblasts as well as to a new formation of basic substance and connective tissue fibers. Normally, this reaction is strictly regulated, which means that after the damage has been removed or the wound has healed, the activity of the fibroblasts is inhibited: on the one hand by the lower release of messenger substances, on the other hand by the programmed cell death ( apoptosis ) of the fibroblasts. These regulatory mechanisms do not work adequately in pulmonary fibrosis. This leads to too much connective tissue being formed. The alveolar septa become wider, so that there is a gas exchange or diffusion disorder ( respiratory insufficiency ). In addition, the lungs lose their flexibility ( compliance ) and can only expand sufficiently during inhalation through increased work of breathing. A so-called restrictive ventilation disorder develops . Both factors - the gas exchange disorder and the restrictive ventilation disorder - lead to the main symptom of pulmonary fibrosis, dyspnoea. In advanced stages of pulmonary fibrosis, the fibroblasts also migrate into the lumen of the alveoli, where they also form new connective tissue. Fibrotic areas form in the alveoli, which are known as fibrotic foci . This destroys the structure of the lungs in these areas, which is accompanied by a complete loss of function.

Symptoms

The main symptom of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, like most other interstitial lung diseases, is shortness of breath, which occurs in the initial stage only with physical exertion. Since IIP is typically a restrictive ventilation disorder, those affected primarily have difficulty breathing in. With advanced severity ( progression ) of the disease, the dyspnoea can, depending on the form of the disease, also occur at rest and in the end stage the diseases can turn into respiratory insufficiency. Pulmonary fibrosis is also characterized by a dry cough without expectoration .

Due to the restricted functionality of the lungs in terms of gas exchange and compliance, there can be an oxygen deficiency in the blood, a so-called hypoxemia . This can manifest itself in the form of cyanosis , i.e. a purple to bluish discoloration of the skin, mucous membranes and fingernails. Also clubbing and Watchglass can form as a sign of hypoxemia. Disturbances in consciousness can also occur in the event of severe oxygen deficiency .

diagnosis

Basic diagnostics

Medical history and physical examination

At the beginning of the examination there is a detailed medical history ( anamnesis ). Among other things, the patients are asked about their current complaints, known illnesses, medications they have taken and illnesses in their relatives. The anamnesis is very important as it helps to rule out other diseases and to make a suspected diagnosis. In the case of many diseases, the patient describes characteristic symptoms, so that the suspected diagnosis often turns out to be the correct one after further examinations.

The Frankfurter Bogen , which is widely used in German-speaking countries, can be helpful for lung diseases . This form is filled out by the patient and takes into account almost all important aspects that are important in the case of lung diseases. The symptoms of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia are non-specific. The shortness of breath, which occurs in all forms of IIP, indicates that there may be a lung disease, but it can also be caused by numerous other diseases, such as heart disease. This also applies in a similar way to the other symptoms described. The diagnosis or the suspected diagnosis of IIP cannot therefore be made solely on the basis of the anamnesis.

The medical history is usually followed by a detailed physical exam . In the case of lung diseases, the focus is on observing ( inspecting ) the entire body surface, tapping ( percussion ) the chest and listening ( auscultation ) of the lungs with a stethoscope . It is primarily the changes that are typical of fibrosis that can be revealed during an IIP with a physical examination. Often one can hear a clear crackling rattle in auscultation , which is also known as sclerophony and is characterized by fine-bubble background noises that occur towards the end of inhalation and exhalation. With the help of percussion, the raised lung boundaries, which are also typical of pulmonary fibrosis, can be revealed. The symptoms cyanosis, drumstick fingers and watch glass nails already mentioned are noticed during the inspection. The physical examination does not allow a reliable diagnosis in IIP either, but it can further limit the field of possible diseases.

Technical investigation procedures

Basic diagnostics for suspected ILD or IIP include technical examination procedures, in particular the examination of lung function and an X-ray of the chest. Body plethysmography plays an important role in evaluating lung function . Pulmonary fibrosis results in a restrictive ventilation disorder, which can be detected using this method. In the early stages of the disease, however, there may be no evidence of such a disorder. A blood gas analysis before and after physical exertion as well as the determination of the CO transfer factor can provide information about the presence of an IIP even in the early stages. Both examination methods also belong to the repertoire of basic diagnostics.

Fibrotic changes can also be made visible on x-rays of the lungs. Here too, changes in the early stages can be so minor that they cannot be used with conventional X-ray diagnostics. Typical signs of pulmonary fibrosis on X-rays are consolidations , traction bronchiectasis and frosted glass shadows. Consolidations are caused by fibrotic tissue in the alveoli and appear as bright areas in the X-ray image, as they are electron-dense than air-filled alveoli. Traction bronchiectasis is a widening of the bronchi and is caused by the tension that is placed on them, which in pulmonary fibrosis is caused by the shrinkage of the lung tissue. The frosted glass shadows are also light areas that are caused by the destruction of the lung architecture.

Further diagnostics

If, after the basic diagnosis, there is an urgent suspicion of IIP, a special computed tomography (CT), known as high resolution CT , is usually performed. Compared to normal CT, this achieves a higher resolution. With HRCT, most cases of IIP can be identified with a high degree of probability and the various forms of disease can be differentiated. Typical characteristics of pulmonary fibrosis in CT in addition to milk glass shading and Traktionsbronchiektasien a so-called honeycomb lung or short honeycomb (engl. Honeycombing ). The honeycomb lung is named because of its similar structure to the honeycomb . The honeycombs arise as a result of the degeneration of the lung tissue.

If a diagnosis or differentiation is not possible with this method, invasive examination procedures must be used. The first step in invasive examinations is bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial biopsy . If this also does not exclude or confirm the diagnosis, a thoracotomy (open lung biopsy) or video-assisted thoracoscopy ( VATS ) must be performed, which is the gold standard in the diagnosis of IIP. According to the recommendations of the consensus conference, at least three samples should be taken from different lung lobes, each with a minimum size of 2 cm.

therapy

Pharmacological therapy

Therapy for idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) is essentially carried out with two groups of drugs. On the one hand with a glucocorticoid , such as prednisolone , and on the other hand with so-called immunosuppressants , especially azathioprine and cyclophosphamide . The effectiveness of the medication depends on the type of IIP the patient is suffering from. While pharmacological therapy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) has no or only a temporary effect on the course of the disease, the other forms respond well to anti-inflammatory therapy, so that healing occurs or at least the mean survival time can be extended considerably.

The different responses to anti-inflammatory therapy are likely due to a different pathogenesis of the various forms. According to the current state of research, fibrosis is in the foreground in IPF and AIP and the inflammatory reaction is only an accompanying reaction or a consequence of it. In the other forms, on the other hand, it is the inflammation of the pulmonary interstitium which determines the course of the disease and which is only superimposed by fibrosis in the end-stage of the disease.

For the therapy of IPF and AIP, great hopes are therefore placed in substances that can inhibit the progression of fibrosis, i.e. the cell proliferation of fibroblasts and collagen synthesis. A large number of such substances are currently (2008) in clinical studies . However, they have not yet been approved for the standard therapy of IIP.

Lung transplant

A lung transplant may be considered if the IIP or pulmonary fibrosis is in the final stages and does not respond to drug therapy. Lung transplantation increases the survival rate in advanced lung fibrosis. The transplantation of one lung is equivalent to the transplantation of two lungs. The indication for a lung transplant is often not made in time. According to a study that included 1,376 patients, more than 30 percent died from waiting long before the lung transplant could be performed.

Clinical differences in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF)

The idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is the most common IIP and has the worst prognosis. The average survival time after diagnosis averages three years and the five-year survival rate is between 20 and 40 percent. The patients are usually older than 60 years at the time of diagnosis and men are affected somewhat more often than women. The incidence is about 6 / 100,000.

The morphological changes are mainly localized in the area of the base of the lungs, i.e. in the lower area of the lungs. The typical histologic pattern of the IPF is called U sual I nterstitial P neumonia designated (UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia), and is characterized by a patchy fibrosis as well as a honeycomb-like structure of the lung. The pattern of UIP is characteristic, but not specific, of IPF and occurs in other interstitial lung diseases as well. In the advanced stages of the disease, the x-ray shows a basal reticular (reticular) vascular pattern. In HRCT (high resolution computed tomography) traction bronchiectasis and honeycombs with a basal and subpleural distribution are typical.

The onset of the disease of IPF is insidious and characterized by increasing shortness of breath, dry, tickly cough and crackling at the lung auscultation. IPF can also occur in the course of existing lung diseases, for example combined with emphysema in COPD ; Smoking is also a risk factor for IPF. The IPF usually does not respond to therapy with glucocorticoids, even in combination with immunosuppressive drugs. Lung transplantation is seen as an effective therapeutic measure in special cases. Pirfenidone (trade name Esbriet® ) has been approved as a drug in the EU since 2011 and in the USA since 2014 for cases that are not yet very advanced. According to initial data, this active ingredient slows the course of the disease; Common side effects are dizziness, nausea, skin rash, increased sensitivity of the skin to light. In 2015, nintedanib (trade name Ofev® ) was approved for all disease stages of IPF in the US and Europe.

Non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP)

The non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) is under the idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP), the second most common and most variants form. Those affected are mostly between 50 and 60 years old and thus on average somewhat younger than patients suffering from IPF. Women and men are equally affected.

The NSIP shows no typical localization with regard to the morphological changes. Rather, the changes are homogeneous and mostly symmetrically distributed over the entire lung. The histological pattern is also referred to as NSIP. There are two subgroups (subtypes) of NSIP, a cellular and a fibrotic subtype. In the cellular subtype, the histological appearance is dominated by inflammatory cells, in the fibrotic subtype there are also pronounced areas of fibrosis. Like the histological picture, the radiological picture is also rich in variations. In addition to diffusely distributed milk glass opacities, there are micronodules and honeycombs. In advanced stages, the normal lung structure is difficult to see in the X-ray and CT images because it has been destroyed by bronchiectasis, cysts and consolidations.

The symptoms of NSIP differ only slightly from those of IPF. However, it has a milder course, progresses more slowly and has a better prognosis. The prognosis also depends on the histological subtype and is better for the cellular subtype than for the fibrotic subtype, as this is more responsive to anti-inflammatory therapy. Overall, drug therapy is much more promising than is the case with IPF. Since the morphological changes of the NSIP are so varied, the diagnosis is the most difficult for doctors compared to other IIPs. This is especially true of the fibrotic subtype.

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia (COP)

As cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (cryptogenic organizing pneumonia) a clinical picture is referred to, the clinical, radiological and pathological features are quite characteristic. As with NSIP, there is no gender preference in COP and the average age of patients is between 50 and 60 years. Non-smokers are affected roughly twice as often as cigarette smokers. The cause of this statistical abnormality is not known.

The histological pattern is called organizing pneumonia (OP). It is characterized by the appearance of granulation tissue filling the bronchioles and alveoli. These changes do not destroy the parenchyma of the lungs. This pattern rarely occurs in the idiopathic form. Often other diseases can be held responsible for these changes as a secondary cause, for example collagenoses and infectious - or drug-induced diseases. A similar histology occurs in bronchiolitis obliterans . For this reason, COP was previously also known as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) . In order to avoid confusion with the independent clinical picture of bronchiolitis obliterans, this term is no longer in use. The granulation tissue appears on X-ray and CT images in the form of so-called consolidation areas , which are mainly located in the area around the bronchi (peribronchial) and directly under the pleura (subpleural). Frosted glass shading can occur around the consolidations.

The clinical picture usually begins with general symptoms such as malaise, fever , weight loss and a dry cough. Symptoms increase within one to three months. COP can be treated well with glucocorticoids and has a good prognosis. The disease often flares up again after discontinuing therapy. This is known as relapse . If relapses occur, the disease can be treated again with glucocorticoids.

Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP)

In contrast to the other idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP), acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) has an acute course. It is characterized by the sudden onset of symptoms and often results in a progressive breathing disorder ( respiratory failure ). The disease has the worst prognosis of IIP. The course is fatal in over half of the cases. Most deaths occur one to two months after the onset of the disease.

The onset of AIP is often preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection , which can be characterized by a general feeling of illness, aching limbs , fever, and chills. The patient then develops shortness of breath (dyspnea) within a few days, which initially only occurs during exercise. A lack of oxygen in the blood (hypoxemia) can already be detected in the early stages. Another characteristic is a clear crackling rattle, which is to be assessed as a sign of consolidation in the context of a restrictive ventilation disorder. The lack of oxygen in the blood ( hypoxemia ) develops into breathing difficulties at rest (resting dyspnea) within a few weeks, which can turn into respiratory insufficiency. At this stage, the patient must be supplied with oxygen and, under certain circumstances, mechanically ventilated.

The histologic pattern is as diffuse alveolar damage (Engl. Diffuse alveolar damage , short- DAD ) called and can not be distinguished from pathological changes in acute adult respiratory distress syndrome (Engl. Acute respiratory distress syndrome , short ARDS ) can occur. AIP and ARDS only differ in the cause. While ARDS occurs primarily in the context of sepsis or shock , the cause of AIP is unknown. Louis Virgil Hamman and Arnold Rice Rich described similar cases as early as the 1940s, which were later summarized as Hamman-Rich syndrome . Probably these cases are the description of what is now called AIP.

Respiratory bronchiolitis with interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD) and desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP)

When respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease and desquamative interstitial pneumonia is disease with a similar but distinguishable appearance. Both diseases occur primarily in smokers, the RB-ILD exclusively and the DIP as a rule. The mean age of onset is around 40–50 years and men are affected about twice as often as women. The RB-ILD is the symptomatic variant of respiratory bronchiolitis, an inflammation of the bronchioles that can be found regularly by chance in smokers. The histological pattern of the asymptomatic and the symptomatic variant is also referred to as respiratory bronchiolitis (RB).

The DIP is viewed by some experts as the advanced variant of the RB-ILD. This is doubtful, however, since DIP, in contrast to RB-ILD, occasionally also occurs in non-smokers and because of the considerable morphological differences (see below). Due to this uncertainty, the consensus classification provides for a separation of the two variants. The term DIP was introduced in 1969 by Liebow and Carrington under the false assumption that these cell clusters were peeling off the alveolar epithelium. This peeling of cells is called desquamation (from the Latin squama "scale"). Nevertheless, the term DIP has been retained in the current classification, partly because DIP is a rarity and has not been replaced by the more fitting term alveolar macrophage pneumonia . The histological pattern of the DIP is also referred to as the DIP.

The histological picture of both forms is characterized by numerous accumulations of brown pigmented macrophages in the lungs. In RB-ILD, the pigmented macrophages are predominantly located in the lumina of the bronchioles (bronchiolocentric), while in DIP they are predominantly found in the lumina of the alveoli (intraalveolar). Mild fibrosis is also characteristic of DIP. The two clinical pictures also differ in the distribution of the morphological changes. While the RB-ILD is mainly found in the upper lobes of the lungs, the DIP has a preferred subpleural location with dominance in the lower lobes. This distribution pattern is particularly easy to detect in the HRCT. So-called centrilobular nodules are characteristic of RB-ILD, and frosted glass shadows are characteristic of DIP.

The clinical symptoms are characterized by a slow development of shortness of breath and dry, tickly cough. In about half of the patients there are also drumstick fingers. Both forms respond well to glucocorticoids and have a good prognosis. Only in rare cases does DIP develop a respiratory failure that has a high mortality rate.

Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonia (LIP)

LIP occurs primarily in women with an age peak around 50 years of age. In the idiopathic form, LIP is the rarest IIP. It occurs much more frequently as a secondary occurrence in the context of autoimmune diseases and immunodeficiency .

The histological pattern, like the clinical diagnosis, is called LIP and is characterized by infiltration of the alveolar septa with lymphocytes and macrophages and the peribronchial formation of lymph follicles . The changes are diffuse throughout the lungs. In the HRCT, frosted glass shadows are characteristic.

The patients have only a few symptoms and mainly suffer from slight shortness of breath and cough. In the secondary forms, the symptoms of the underlying disease are in the foreground. In rare cases, LIP can develop into pulmonary fibrosis or malignant lymphoma . Aside from this complication, LIP has a good prognosis. The therapy is usually carried out with glucocorticoids, the effectiveness of which has not yet been proven in this form of IIP in randomized studies.

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia in animals

The group of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia in animals has so far been little studied. Therefore, there is also no suitable model animal for basic studies - bleomycin- induced pulmonary fibrosis in rodents is only a disease that is ( phenomenologically ) similar in appearance , but does not meet the requirements of an adequate model.

Such chronic idiopathic diseases can be found more frequently in some terrier breeds ( West Highland White Terrier , Staffordshire Bull Terrier , Scottish Terrier ). The canine idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis occurs mainly in older animals and corresponds to the cryptogenic organizing pneumonia in humans. Only a few cases of IIP have been described in the literature in cats; according to a recent study, it corresponds to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in humans and is probably caused by a defect in the type II pneumocytes .

In birds, there has so far only been a single case report of a blue-fronted parrot .

Research history

AIP (acute interstitial pneumonia),

BIP (bronchiolitic interstitial pneumonia),

BOOP (bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia),

COP (cryptogenic interstitial pneumonia),

DIP (desquamative interstitial pneumonia),

GIP (giant cell pneumonia),

LPD (lymphoproliferative diseases),

LIP (lymphoid interstitial pneumonia),

NSIP ( nonspecific interstitial pneumonia),

RB-ILD (respiratory bronchiolitis with interstitial lung disease),

UIP (usual interstitial pneumonia).

The first description of an interstitial lung disease dates back to 1892 and comes from the Canadian physician William Osler . He already recognized the diverse appearance and pointed out the necessity and difficulty of a further classification of the changes.

In 1944 the internist Louis Virgil Hamman and the pathologist Arnold Rice Rich reported on four patient cases who were affected by acute diffuse interstitial fibrosis. The Hamman-Rich Syndrome was named after them. This term was then used for a while for all diseases in which there was a chronic diffuse fibrosis of the lungs with an unknown cause, although the cases described were acute. The authors probably described what is now called acute interstitial pneumonia.

The first histological classification of idiopathic interstitial lung diseases comes from the two pathologists Averill Abraham Liebow and Charles B. Carrington (1969). The classification at that time distinguished five histological patterns, which were first included under the generic term idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis . The Hamman-Rich syndrome was as acute variant of the " U sual I nterstitial P classified neumonia" (UIP, ordinary interstitial pneumonia).

The Liebow-Carrington classification was further developed in 1997 by Anna-Luise A. Katzenstein and in 1998 in collaboration with Jeffrey L. Myers and adapted to the current state of research. The cause of the " G iant I nterstial P neumonia" (GCP, giant cell pneumonia) has now been elucidated. It is triggered by the inhalation of metal dust and is known as hard metal fibrosis. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia was assigned to the "lymphoproliferative diseases" (LPD, lymphoproliferative diseases).

Individual evidence

- Note : The article builds on the 2002 Consensus Conference publication, unless otherwise indicated: American Thoracic Society / European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. In: Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 165 (2), Jan 15, 2002, pp. 277-304. PMID 11790668 . doi : 10.1164 / ajrccm.165.2.ats01 .

- ↑ a b c d American Thoracic Society / European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. In: Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 165 (2), Jan 15, 2002, pp. 277-304. PMID 11790668 . doi : 10.1164 / ajrccm.165.2.ats01 .

- ↑ GW Hunninghake, MI Schwarz: State of the art. Does current knowledge explain the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis ?: a perspective. In: Proc Am Thorac Soc. 4 (5), Sep 2007, pp. 449-452. PMID 17684287 . doi : 10.1513 / pats.200702-036MS .

- ^ KO Leslie: Historical perspective: a pathologic approach to the classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. In: Chest. 128 (5 Suppl 1), Nov 2005, pp. 513S-519S. PMID 16304241 . doi : 10.1378 / chest.128.5_suppl_1.513S .

- ↑ U. Costabel: Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias - Why Another Consensus Classification? In: Pneumology. 56, 2002, pp. 279-280. doi : 10.1055 / s-2002-30703 .

- ^ DB Coultas et al .: The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. In: Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. Vol 150, No. 4, 10, 1994, pp. 967-972. doi : 10.1164 / ajrccm.150.4.7921471 .

- ↑ G. Raghu et al .: Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. In: Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 174 (7), Oct 1, 2006, pp. 810-816. Epub 2006 Jun 29. PMID 16809633 . doi : 10.1164 / rccm.200602-163OC .

- ^ Francis HY Green: Overview of Pulmonary Fibrosis. In: Chest. 122, 2002, pp. 334S-339S. doi : 10.1378 / chest.122.6_suppl.334S .

- ^ JE Gadek et al: Role of connective tissue proteases in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory lung disease. In: Environ Health Perspect . 55, Apr 1984, pp. 297-306. PMID 6329673 . doi : 10.1289 / ehp.8455297 .

- ^ TE King: Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: progress in classification, diagnosis, pathogenesis and management. In: Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 115, 2004, pp. 43-78. PMID 17060957 .

- ↑ Gross et al .: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. In: N Engl J Med . 345, 2001, pp. 517-525. doi : 10.1056 / NEJMra003200 .

- ^ BC Willis et al.: Epithelial origin of myofibroblasts during fibrosis in the lung. In: Proc Am Thorac Soc. 3 (4), Jun 2006, pp. 377-382. PMID 16738204 . doi : 10.1513 / pats.200601-004TK .

- ↑ R. Klinke, S. Silbernagl (Ed.): Textbook of Physiology. 4th edition. Thieme-Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-13-796004-5 .

- ↑ M. Dietel et al. a :: Harrison's internal medicine. 15th edition. ABW Wissenschaftsverlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-936072-10-8 .

- ↑ H. Kronenberger et al.: A new questionnaire for recording lung and respiratory diseases. In: Prax. Clin. Pneumol. 39, 1985, pp. 241-251.

- ↑ a b c Günther et al: Classification, diagnosis and therapy of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: A critical inventory of the practice currently practiced in Germany. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. June 24, 2003. ( html version ), (PDF version) ( Memento from July 30, 2004 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ a b Kauffmann et al .: Radiology. 3. Edition. Urban & Fischer Munich / Jena 2006, ISBN 3-437-44415-8 .

- ↑ U. Costabel et al.: Pulmonary fibroses - classification, diagnosis, therapy. In: Internist. [Suppl 1] 44, 2003, pp. S35-S43. doi : 10.1007 / s00108-003-0977-6 .

- ↑ JD Hosenpud et al .: Effect of diagnosis on survival benefit of lung transplantation for end-stage lung disease. In: The Lancet . 351 (9095), Jan 3, 1998, pp. 24-27. PMID 9433425 . doi : 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (97) 06405-2 .

- ↑ BF Meyers et al .: Single versus bilateral lung transplantation for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a ten-year institutional experience. In: J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg . 120, 2000, pp. 99-107. PMID 10884661 . doi : 10.1067 / mtc.2000.106322 .

- ↑ J. De Meester et al: Lung transplant waiting list: differential outcome of type of end-stage lung disease, one year after registration. In: J Heart Lung Transplant . 18 (6), Jun 1999, pp. 563-571. PMID 10395354 . doi : 10.1016 / s1053-2498 (99) 00002-9 .

- ^ DS Kim et al .: Classification and natural history of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. In: Proc Am Thorac Soc. 3 (4), Jun 2006, pp. 285-292. PMID 16738191 . doi : 10.1513 / pats.200601-005TK .

- ↑ David A Lynch, Nicola Sverzellati, William D Travis, Kevin K Brown, Thomas V Colby: Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Fleischner Society White Paper . In: The Lancet Respiratory Medicine . tape 6 , no. 2 , February 2018, p. 138-153 , doi : 10.1016 / S2213-2600 (17) 30433-2 .

- ↑ PW Noble et al .: Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomized trials. In: Lancet. 377 (9779), May 21, 2011, pp. 1760-1769. doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (11) 60405-4 . Epub 2011 May 13.

- ^ H. Monaghan et al .: Prognostic implications of histologic patterns in multiple surgical lung biopsies from patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. In: Chest. 125 (2), Feb 2004, pp. 522-526. PMID 14769733 . doi : 10.1378 / chest.125.2.522 .

- ↑ See also Joachim Frey : Diseases of the respiratory organs. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (ed.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition ibid. 1961, pp. 599-746, here: p. 708 ( Diffuse progressive interstitial pulmonary fibrosis : pulmonary fibrosis (Hamman-Rich 1944)).

- ↑ a b K. Williams et al: Identification of spontaneous feline idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: morphology and ultrastructural evidence for a type II pneumocyte defect. In: Chest. 125 (6), Jun 2004, pp. 2278-2288. PMID 15189952 . doi : 10.1378 / chest.125.6.2278 .

- ^ BM Corcoran et al.: Chronic pulmonary disease in West Highland white terriers. In: Vet Rec. 144 (22), May 29, 1999, pp. 611-616. PMID 16119057

- ↑ LA Cohn et al: Identification and characterization of an idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-like condition in cats. In: J Vet Intern Med. 18 (5), Sep-Oct 2004, pp. 632-641. PMID 15515577 . doi : 10.1111 / j.1939-1676.2004.tb02598.x .

- ↑ O. Amann et al .: Chronic pulmonary interstitial fibrosis in a blue-fronted Amazon parrot (Amazona aestiva aestiva). In: Avian Dis. 51 (1), Mar 2007, pp. 150-153. PMID 17461284 . doi : 10.1637 / 0005-2086 (2007) 051 [0150: CPIFIA] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ^ A. Katzenstein, J. Myers: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis - Clinical Relevance of Pathologic Classification. In: Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 157 (4 Pt 1), Apr 1998, pp. 1301-1315. PMID 9563754 . doi : 10.1164 / ajrccm.157.4.9707039 .

- ^ R. Collard et al: Demystifying Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia. In: Arch Intern Med . 163, 2003, pp. 17-29. PMID 12523913 . doi : 10.1001 / archinte.163.1.17 .

literature

- J. Müller-Quernheim: Interstitial lung diseases . Thieme, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-13-132281-0 .

- H. Schweisfurth et al: How are interstitial lung diseases diagnosed in Germany? In: Pneumology. 57, 2003, pp. 373-382. doi: 10.1055 / s-2003-40557