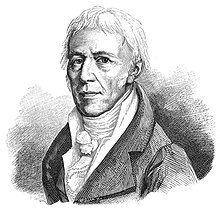

Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de Lamarck (born August 1, 1744 in Bazentin-le-Petit ( Département Somme ), † December 18, 1829 in Paris ) was a French botanist , zoologist and developmental biologist . Lamarck is the founder of the modern zoology of invertebrates , he used and defined the term " biology " introduced by Michael Christoph Hanow in 1766 at the same time as Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus for the first time in his 1802 publication Hydrogéologie, and was the first to present a fully formulated theory of evolution . This includes as the main principle a directed higher development through repeated spontaneous generation of living beings, through which the individual classes arise; and as a secondary principle the inheritance of acquired traits that he believes is possible, which should lead to biodiversity (variability of animal classes). Only this secondary principle has been called Lamarckism since the late 19th century . Its botanical author abbreviation is “ Lam. "

Life

Lamarck was born on August 1, 1744 as the 11th child of Philippe Jacques de Monet de La Marck and Marie-Françoise de Fontaine de Chuignolles in Bazentin-le-Petit, a small town in Picardy . The family belonged to the lower nobility and was not well off. A career as a clergyman was planned for Jean-Baptiste, he attended the Jesuit college in Amiens from the age of 11 . After the death of his father in 1759, however, he joined the army. He took part in the Seven Years War and was then stationed in various forts on the eastern border as well as on the Mediterranean coast. In 1768 he quit military service for health reasons (because of a "glandular disease"). In Paris he then worked in a bank and studied medicine from 1770 to 1774 without graduating. During his studies he got to know France's scientific elite, above all the botanists Bernard de Jussieu and Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu and the zoologist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon .

At this time Lamarck, who from the age of 30 devoted himself entirely to the natural sciences (biology, physics, chemistry, meteorology and geology, but above all botany), was already a specialist in the French flora, also benefiting from his numerous stationing locations. In the 1770s he wrote a Flore française (French flora), which was printed in 1779 as a three-volume work at state expense through Buffon's mediation. This work established Lamarck's reputation as a scientist. In the same year he was accepted into the Paris Académie des Sciences , in 1781 he became a correspondant at the Jardin des Plantes . Since these positions were not associated with an income, he earned his living in the 1780s as a collaborator in various scientific encyclopedias: He wrote the first three volumes of the eight-volume Encyclopédie méthodique: botanique , including the parallel work, the six-volume Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique des trois règnes de la Nature: botanique (1791–1823) he worked with. In 1788 he received the modestly paid position as curator of the herbarium at the Jardin des Plantes with the title Botanist du roi avec le soin et la garde des herbiers .

When the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle was founded in Paris in 1793, the botanist Lamarck was entrusted by its first director, Louis Jean-Marie Daubenton , with the zoological professorship for the Linnaeus animal classes of insects and worms. However, he had already made a name for himself as a mussel expert. The second professorship in zoology, that of vertebrates, was held by Daubenton with Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, who is known as a mineralogist . At the age of 49 and as the father of six children, Lamarck was given a secure position. In addition to the organization and order of the museum's holdings, his tasks also included scientific teaching. A work on mussels, completed in 1798, never appeared.

In 1801 he published his first important work in his new field of work: Système des animaux sans vertèbres, in which he coined the term invertebrate , which is still used today . Between 1815 and 1822 the Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres appeared in seven volumes , which represents the actual beginning of the zoology of invertebrates. Since 1808 he was a foreign member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences .

In addition to zoology, Lamarck dealt with a variety of topics, on which he also presented detailed publications. So he tried a new foundation of chemistry and physics, he turned against the oxidation chemistry founded by Lavoisier, published meteorological yearbooks for 10 years and published a geological theory in his Hydrogéologie in 1802 , with which he explained the formation and shape of the earth . In the same year he put in Recherches sur l'organization des corps vivants his views on the physico-chemical theory of life processes. With the two volumes of Introduction à la botanique, the volume 15 for Histoire naturelle des végétaux published include it be last botanical work. In 1809 he published his doctrine of transformation in his Philosophy zoologique . His work on physics , chemistry, geology , meteorology and physiology is more extensive than that on invertebrate zoology. However, they did not meet with any approval in the professional world, so Lamarck felt increasingly misunderstood, even ostracized. In later years he believed in conspiracies against himself, especially by Georges Cuvier . He was blind for the last ten years of his life. Lamarck died bitterly without ever having been wealthy on December 28, 1829 in Paris and was buried in a poor grave. Lamarck was married three times and had eight children.

Honors

The lunar crater Lamarck is named after him. The same applies to Lamarck Island in Antarctica. The plant genera Lamarckia Moench from the sweet grass family (Poaceae), Markea Rich. from the nightshade family (Solanaceae), Monetia L'Hér. from the family of Salvadoraceae and Neolamarckia Bosser from the family of the redness plants (Rubiaceae) are named after him.

plant

Systematics

Lamarck differentiated in the systematics between classification and distribution : Classification (division, assignment) is for him the identification and differentiation of taxa at the different ranks ( species , genera , families , etc.), as well as the assignment of a taxon to the higher ranking. For Lamarck, distribution is the ratio of different taxa of equal rank to one another, their affinité (relationship), whereby relationship at that time did not mean genealogical relationship based on common ancestors.

Lamarck rejected the continuity of all three kingdoms of nature , which was widespread at the time, but followed the principle of continuity within the three kingdoms (minerals, plants, animals): the chain of beings is linked by continuous transitions. Lamarck was also a supporter of the step ladder principle , according to which the taxa can be arranged in an ascending order according to the degree of their perfection.

In his botanical work, Lamarck was able to fall back on existing classification systems. Important work in this area was done by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort , Carl von Linné , Michel Adanson and Bernard de Jussieu . His Flore Françoise , however, was one of the first systematic inventories of a regional flora. Lamarck introduced a diagnostic key that made a simple determination of the species possible through dichotomous distinctions. The linear arrangement of the taxa resulting from the principle of continuity contradicted Linnaeus' sexual system. This contradiction to Linnaeus brought Lamarck, among other things, the protection and promotion of Buffon. However, he could not implement the principle of the step ladder in botany.

In the case of invertebrates, the classification meant most of the work, since Lamarck could not actually rely on any useful preliminary work here; he had to work out the entire classification himself. In doing so, he was able to fall back on the large collections of the museum. Linnaeus had only differentiated between two classes of invertebrates: insects and worms , the latter a remnant class in which everything was gathered that did not fit into the other classes. In 1795 Lamarck used six classes that may go back to Cuvier: mollusks (molluscs), crustaceans (crustaceans), insects, worms, echinoderms and zoophytes. This number increased to ten classes in 1809, which in turn were heavily subdivided: molluscs, barnacles , annelids , crustaceans, arachnids , insects, worms, radiant animals , cnidarians (polyps) and infusoria . This structure remained the standard for around half a century. Lamarck also relied on the work of colleagues, especially Jean Guillaume Bruguière , Guillaume-Antoine Olivier and Georges Cuvier .

Lamarck initially represented the arrangement of the animals as a linear step ladder. Later, however, he arranged them with branches. However, he insisted that the order must be based on the perfection of the classes. This contradicted his colleague at the museum, Cuvier, who had already questioned the ladder principle at the time. At that time, however, the step ladder principle was already one of the foundations for Lamarck's transformation theory.

Physique terrestre

Between 1793 and 1809 Lamarck published several works, some in several volumes, which dealt with physics, chemistry, geology and meteorology. Lamarck's goal was to present the processes of the lithosphere , biosphere and atmosphere in a three-volume Physique terrestre . His physical and chemical theories were less concerned with the fundamentals of physics and chemistry than with the fundamental processes in the lithosphere, biosphere and atmosphere. One of his chemical theories was that all chemical compounds tend to decay. Connections could only arise in living organisms through the vital principle inherent in them. Lamarck was thus in the tradition of vitalism . This strict separation between inanimate and animate led to the pair of terms organic / inorganic and also to the fact that Lamarck was one of those who introduced the term biology around 1800. This chemical theory, however, meant that life could only ever arise from already existing life, so spontaneous generation was impossible. Independently of this, however, Lamarck postulated in 1801 in Système des animaux sans vertèbres that the primitive representatives of animals and plants are brought about by nature, that is, arise through spontaneous generation. This later became important to his transformation theory. Lamarck never resolved this contradiction in terms of spontaneous generation.

Also around the turn of the century, Lamarck accepted that species can also become extinct. He had previously declined this option, as extinction events were always associated with disasters . However, Lamarck was a representative of actualism and uniformism in geology, so he was of the opinion that in the past the same geological forces were at work to the same extent as they are today.

Evolution theory

Around 1800 Lamarck developed a theory of species transformation, the variability of species . The ways of thinking that led him to this are not known, the following are discussed as important factors: His findings as a systematist that the classes can be ranked linearly according to their complexity; his shift from a vitalistic to a mechanistic physiology; resulting from the possibility of spontaneous generation and an epigenetic view of ontogeny ; his project of the Physique terrestre, within which the transformation formed the explanation for the diversity of living beings. Another starting point was possibly the discussion that took place in Paris in the 1790s as to whether species could become extinct. For Lamarck, the variability of species was a way of reconciling the notion of extinction, which he rejected, on the one hand, and the fossil record on the other.

According to Lamarck's theory, the simplest organisms arise through spontaneous generation . Spontaneous generation still takes place in the present. These organisms develop into more and more complex forms, whereby a sense of direction is inherent in the development: from simple to complex. Plants and animals therefore developed independently of one another. This theory is also a pure transformation theory; in contrast to Darwin's theory, it does not contain any common ancestry of all species. The individual animal classes were created independently of one another. The classes have similar ancestors, the forms created by spontaneous generation, but no common ancestors. Their respective higher development therefore runs parallel and independently of one another. The higher development takes place on the basis of a process established and determined in the organism. So Lamarck's evolution is directed, if not toward a predetermined goal.

In his Philosophy zoologique (1809) Lamarck also provides philosophical considerations on a possible origin of humans (bimanes) from a "race" of monkeys (quadrumanes) :

“If, in fact, any monkey race, chiefly the most perfect of these, has been compelled by circumstances or by some other cause, the habit of climbing the trees and grasping the branches with both feet and hands in order to look at them to hang up, to give up, and if the individuals of this race have been compelled for a long line of generations to use their feet only for walking and to cease to make the same use of their feet as they do of their hands, it is according to the remarks made in the previous chapter It is not doubtful that the four-handed hands were finally transformed into two-handed hands and that the thumbs of their feet, since these feet were only used for walking, lost the opposition to the fingers. Furthermore, if the individuals I speak of, moved by the need to rule and at the same time to see each other far and wide, made an effort to stand upright, and clung to this habit from generation to generation, then it is not doubtful, that their feet imperceptibly acquired a suitable formation for an upright posture, that their legs got calves and that these animals could then only walk with difficulty on their hands and feet at the same time. "

Lamarck explained the diversity of the species and the deviations from the pure sequence of stages with a second mechanism, which acts as a secondary principle for higher development: changed environmental conditions cause animals to change "habits" , which lead to changed use of organs. The changed use leads to modifications of the organ, which are passed on to the offspring. This subsidiary principle was not developed by Lamarck; the inheritance of acquired traits was widely recognized in the 18th and 19th centuries. This part of Lamarck's theory of evolution alone, the inheritance of acquired traits, was later referred to as Lamarckism .

It was not until 1876 that Lamarck's zoological philosophy was published in German, probably as a result of the increased attention paid to the idea of evolution through the work of Charles Darwin (a complete edition of Darwin's works began to appear in German as early as 1875, i.e. during Darwin's lifetime).

Fonts (selection)

- Flore Française: Ou Descriptions Succinctes De Toutes Les Plantes Qui croissent naturellement En France; Disposée selon une nouvelle méthode d'Analyse, et à laquelle on a joint la citation de leurs vertus les moins équivoques en Médicine, et de leur utilité dans les Arts. Paris 1778.

- Encyclopédie Méthodique: Botanique. Paris 1783–1808 - volumes 1 to 3 of a total of 8 volumes ( biodiversitylibrary.org ).

- Mémoires de physique et d'histoire naturelle, établis sur des bâses de raisonnement indépendantes de toute théorie; avec l'exposition de nouvelles considérations sur la cause générale des dissolutions; sur la matière du feu; sur la couleur des corps; sur la formation des composés; sur l'origine des minéraux; et sur l'organization of the corps vivans. Paris 1797.

- Système des animaux sans vertèbres, ou Tableau général des classes, des ordres et des genres de ces animaux présentant leurs caractères essentiels et leur distribution, d'après la considération de leurs rapports naturels et de leur organization, et suivant l'arrangement établi dans les galeries du Muséum d'Hist. Naturelle, parmi leurs dépouilles conservées. Paris 1801.

- Hydrogéologie ou research on the influence qu'ont les eaux on the surface du globe terrestre; sur les causes de l'existence du bassin des mers, de son déplacement et de son transport successif sur les différens points de la surface de ce globe; enfin sur les changemens que les corps vivans exercent sur la nature et l'état de cette surface. Paris 1802 ( lamarck.cnrs.fr [PDF; 1.1 MB]; Text archive - Internet Archive ).

- Research on the organization des corps vivans: et particulièrement sur son origine…: précédé du discours d'ouverture du cours de zoologie donné dans le Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, l'an X de la République. Paris 1802.

- Mémoires sur les fossiles des environs de Paris comprenant la détermination des espèces qui appartiennent aux animaux marins sans vertèbres, et dont la plupart sont figurés dans the collection des vélins du Muséum. Paris 1802.

-

Philosophy zoologique, ou, Exposition des considérations relative à l'histoire naturelle des animaux. Paris 1809 (German translation by Arnold Lang : Jena 1876).

- Reprint as zoological philosophy (= Ostwald's classic of the exact sciences. Volume 277/279). Verlag Harri Deutsch, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-8171-3409-6 , urn : nbn: de: hebis: 30: 3-91710 .

- Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres présentant les caractères généraux et particuliers de ces animaux, leur distribution, leurs genres, et la citation des principales espèces qui s'y rapportent: précédée d'une introduction offrant la détermination des caractères essentiels de l'animal, see distinction du végétal et des autres corps naturels: enfin, l'exposition des principes fondamentaux de la zoologie. Paris 1815-1822.

- Système Analytique des Connaissances Positives de l'Homme. L'auteur, Paris 1820 ( lamarck.cnrs.fr ).

- Alfred Giard (ed.): Discours d'ouverture [des cours de zoologie donnés dans le Muséum d'histoire naturelle, to VIII, to X, to XI et 1806]. Paris 1907 ( gallica.bnf.fr ).

supporting documents

- Wolfgang Lefèvre: Jean Baptiste Lamarck. In: Ilse Jahn, Michael Schmitt: Darwin & Co. A history of biology in portraits. Volume 1. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-44642-6 , pp. 176-201.

further reading

- Madeleine Barthélémy-Madaule: Lamarck ou le mythe du précurseur. Éditions du Seuil, Paris 1979, ISBN 2-01-005239-3 .

- Richard W. Burkhardt: Lamarck, evolution, and the politics of science. In: Journal of the History of Biology. Volume 3, No. 2, 1970, ISSN 0022-5010 , pp. 275-298, doi: 10.1007 / BF00137355 .

- Richard W. Burkhardt: The Spirit of System. Lamarck and Evolutionary Biology. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 1977, ISBN 0-674-83317-1 (2nd print. Now with "Lamarck in 1995". Ibid 1995).

- Leslie J. Burlingame: Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste. In: Charles C. Gillispie (Ed.): Dictionary of Scientific Biography . Volume 7: Iamblichus - Karl Landsteiner. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York NY 1973, ISBN 0-684-10118-1 , pp. 584-594.

- Pietro Corsi: Lamarck. Genèse et enjeux du transformisme. 1770-1830. CNRS Éditions, Paris 2001, ISBN 2-271-05701-9 .

- Pietro Corsi, Jean Gayon, Gabriel Gohau, Stéphane Tirad: Lamarck, philosophe de la nature. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 2006, ISBN 2-13-051976-8 .

- Yves Delange: Lamarck. Sa vie, son œuvre. Actes Sud, Arles 1984.

- Alain Delaunay: Lamarck et la naissance de la biologie. In: Pour la Science. No. 205, November 1994, ISSN 0153-4092 , pp. 30-37 ( sniadecki.wordpress.com ).

- Ludmilla J. Jordanova : Lamarck. Oxford University Press, Oxford u. a. 1984, ISBN 0-19-287588-4 .

- Léon Szyfman: Jean-Baptiste Lamarck et son époque. Masson, Paris a. a. 1982, ISBN 2-225-76087-X .

- Goulven Laurent (ed.): Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829). Éditions du CTHS, Paris 1997, ISBN 2-7355-0364-X .

- Bernard Mantoy: Lamarck. Choix de textes, bibliographie, illustrations (= Savants du monde entier. 36, ZDB -ID 1088216-9 ). Éditions Seghers, Paris 1968.

- Alpheus S. Packard : Lamarck. The Founder of Evolution. His life and work. With translations of his writing on organic evolution. Longmans, Green, and Co., New York NY et al. a. 1901, ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck in the catalog of the German National Library

- Literature by and about Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck in the catalog of the Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Author entry and list of the described plant names for Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck at the IPNI

- Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck (1744-1829)

- Lamarck's theory of evolution ( Memento of February 13, 2008 in the Internet Archive ). In: univie.ac.at

- First part of Lamarck's Zoological Philosophy

- CNRS via Lamarck. (No longer available online.) In: lamarck.cnrs.fr. Archived from the original on August 17, 2019 (French).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Martina Keilbart: Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste-Pierre-Antoine de Monet, Ritter de. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 820 f.

- ↑ a b c Martina Keilbart: Lamarck. 2005, p. 820.

- ^ List of members since 1666: Letter L. Académie des sciences, accessed on January 7, 2020 (French).

- ↑ Lotte Burkhardt: Directory of eponymous plant names. Extended Edition. Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-946292-26-5 , doi: 10.3372 / epolist2018 ( bgbm.org ).

- ^ Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck: Zoological philosophy together with a biographical introduction by Charles Martins. Translated from the French by Arnold Lang . Ambrosius Abel, Leipzig 1873. pp. 190 f.

- ^ Jean-Baptiste de Monet de Lamarck: Philosophy zoologique ou Exposition des considérations relatives à l'histoire naturelle des Animaux. Nouvelle édition. Tome premier (Volume 1). Germer Baillère - Librairie, Paris / Londres / Bruxelles 1830. Distribution générale. Les bimanes. L'homme. P. 348–357, here p. 349 f .: Effectivement, si une race quelconque de quadrumanes, surtout la plus perfectionnée d'entre elles, perdait, par la nécessité des circonstances ou par quelque autre cause, l'habitude de grimper dans les arbres, et d'en empoigner les branches avec les pieds, comme avec les mains, pour s'y accrocher, et si les individus de cette race, pendant une suite de générations, étoient forcés de ne se servir de leurs pieds que pour marcher, et cessoient d'employer leurs mains comme des pieds; il n'est pas douteux, d'après les observations exposées dans le chapitre précédent, que ces quadrumanes ne fussent à la fin transformés en bimanes, et que les pouces de leurs pieds ne cessassent d'être écartés des doigts, ces pieds ne leur servant plus qu'à marcher. En outre, si les individus dont je parle, mus par le besoin de dominer, et de voir à la fois au loin et au large, s' efforçoient de se tenir debout, et en prenoient constamment l'habitude de génération en génération; il n 'est pas douteux encore que leurs pieds ne prissent insensiblement une conformation propre à les tenir dans une attitude redressée, que leurs jambes n'acquissent des mollets, et que ces animaux ne pussent alors marcher que péniblement sur les pieds et les mains à la fois.

- ^ Franz Stuhlhofer : Charles Darwin - World Tour to Agnosticism (= TELOS books. No. 2809). Schwengeler, Berneck 1988, ISBN 3-85666-289-8 , pp. 110-133: “Admission of Darwinism in Germany”.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste de |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet Chevalier de (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French botanist and zoologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 1, 1744 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bazentin-le-Petit |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 18, 1829 |

| Place of death | Paris |