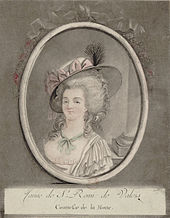

Jeanne de Saint-Rémy

Jeanne de Saint-Rémy (born July 22, 1756 at Fontette Castle in Champagne in what is now the Aube department , † August 23, 1791 in London ) was a French noblewoman and mastermind of the so-called collar affair .

She was descended from an illegitimate son of the French King Henry II and was thus a distant member of the Valois family . Growing up in misery as the child of a completely impoverished nobleman, she received a solid education only thanks to a wealthy benefactress, the Marquise of Boulainvilliers . Since she did not want to come to terms with the life in the monastery intended for her , she fled from Longchamp Abbey and a short time later married a poor country nobleman. The couple had constant financial worries, so the two tried in vain to use Jeanne's royal family tree in Paristo get money. However, through lies and forged letters, the cunning Jeanne was able to embroil the cardinal and grand almsman of France , Louis René Édouard de Rohan , in a fraud that initially brought her a lot of money. When this was discovered, Jeanne de Saint-Rémy finally ended up in the Salpêtrière , where she was able to break out after about a year. She fled to London and wrote her memoirs and an autobiography from exile .

Life

Childhood and adolescence

Jeanne was the second child of Henry de Saint-Rémys, baron de Luz, and his wife Marie Jossel in Fontette . Her father came from an old French but impoverished aristocracy, as he was the eighth generation of Henry de Saint-Rémy, the illegitimate son of Henry II and his mistress Nicole de Savigny . But Jeanne's mother was a commoner, the daughter of a servant Henry de Saint-Remys. On the run from creditors, her parents moved in 1760 with the two eldest of their three children, Jacques (1751–1785) and Jeanne, from Fontette to Boulogne (now Boulogne-Billancourt ), a suburb of Paris. Her youngest, Marie-Anne (1757–1786), the parents left with a local farmer. The mother's death in 1762 made the siblings orphans, because the father had already died in February 1761, shortly before the birth of his third daughter, Marguerite. The three siblings then kept themselves afloat by begging .

Because of her descent from the Valois family, when she was eight years old, Jeanne caught the attention of Adrienne-Marie-Madeleine d'Hallencourt, the Marquise of Boulainvilliers. In her memoirs, Jeanne passed on a heartbreaking story in which, as a begging orphan, she met the Marquise by chance on the street, but the truth was far less fateful: the three needy siblings were recommended to Madame d'Hallencourt by the parish priest of Boulogne. She took care of the neglected children and obtained on December 9, 1776 - after proof of their royal family tree had been provided and the children had been legitimized in the same year - from the President of the royal finance council Louis XV. a pension for the Saint-Rémy orphans, because there were regulations at the time that stipulated that the descendants of noble but impoverished families were entitled to financial support. Jacques was also given a vacancy in the school for naval officers, while Jeanne and her sister Marie-Anne were sent to the Ursuline convent of Ligny-en-Barrois from 1763 at the expense of Madame de Boulainvilliers . There Marguerite died of smallpox . The Marquise then had Jeanne's second sister Marie-Anne von Fontette brought to Ligny. At the age of 14, Jeanne began training as a tailor in a Paris fashion salon, but did not complete her apprenticeship. When she was 16 years old, she and her sister were sent to the Notre-Dame d'Yerres Abbey because the two girls were to become nuns. After two years they moved to Longchamp Abbey. In her later published memoir, Jeanne claims that she voluntarily entered the monastery to avoid the sexual intrusiveness of Anne Gabriel Henri Bernard de Boulainvilliers , the husband of her patroness. When the Superior of Longchamp urged the two sisters to take their vows as nuns, the two fled in 1779 after four years of residence from the convent to Bar-sur-Aube , where - after a short stay in a shabby hostel - they stayed with their aunt Madame de Clausse Sure Mont, the wife of the local Vogts under came. There Jeanne met the young Jacques Claude Beugnot , the future French Minister of State, who fell head over heels in love with the 22-year-old, but Jacques' father sent him to Paris to avoid possible complications. In her aunt's house, Jeanne also met the family's nephew, Marc Antoine Nicolas de La Motte, a gendarmerie officer and little country gentleman whom Jeanne married on June 6, 1780. Her younger sister then retired to Jarcy Abbey near Brie-Comte-Robert .

Countess de La Motte

The marriage did nothing to change Jeanne's poor financial situation, because the new husband was just as poor as his wife. She gave birth to twins a month after they were married, but the two boys died just days after giving birth. The couple assumed the title of Count and Countess de La Motte and went to Lunéville , where Nicolas de La Motte rejoined his regiment . Jeanne's pension, however, was not enough for her and her husband, both in front and behind, and so the couple kept afloat with rip-offs and loans.

In September 1781, Jeanne met her former patron, the Marquise de Boulainvilliers, again in Saverne . She introduced the young woman to Cardinal Louis René Édouard de Rohan , who resided in the castle there . This encounter later turned out to be extremely lucrative for Jeanne. But even in the short term the couple used this acquaintance, because by Rohan recommendation Jeanne's husband got a job in the October 1781 Guard of the Comte d'Artois . In Nicolas de La Motte's certificate of appointment, the title of Count was inadvertently entered, so that he and his wife henceforth called themselves Count and Countess de La Motte.

The couple went to Paris at the end of October 1781 and initially rented a room in the Hôtel de Reims on Rue de la Verrerie to try their luck there. Jeanne wanted to capitalize on her royal ancestry in Versailles and therefore rented a room there on Place Dauphine . She tried several times to have audiences with members of the royal family because she wanted to achieve an increase in her pension. Her family tree was supposed to open the doors to Jeanne, but she was never admitted. The Duchess of Polignac, for example, refused to give her an audience with the queen despite Jeanne's written request. Even a feigned fainting spell in the presence of the queen could not help her to a meeting with Marie Antoinette . Instead, the couple lived in extremely poor conditions and ran into more and more debts. For fear of his creditors, Nicolas even fled to Brie-Comte-Robert for a while, and in 1783 the two of them took their furniture to safety as a precaution because they feared it would be seized. As early as November 1782, Count and Countess La Motte owed their landlord so much money that after a heated argument they had to move out of the Hôtel de Reims and move to another place on Rue Neuve-Saint-Gilles . Although Jeanne's pension had been increased to 1,500 livres on January 18, 1784 at the intercession of the Countess of Provence , the financial worries remained omnipresent. In April of the same year Jeanne therefore sold her entitlement to the annual pension granted by the King for 6,000 livres.

Meanwhile she had met Cardinal Rohan again. Although she had not been able to win him over at the first meeting in Saverne, she did so in Paris in 1782. At the end of the year she was his mistress. After the death of the Marquise de Boulainvilliers, Rohan sometimes helped the penniless Jeanne out with small sums of money. Soon she was not only his lover, but also his close confidante.

The collar affair

Louis René Édouard de Rohan-Guéméné was not only Cardinal Archbishop of Strasbourg , but also Grand Almosenier of France and thus the most important cleric at the French royal court. Nevertheless, Queen Marie Antoinette only showed him contempt, which went back to incidents at the Viennese court, when Marie Antoinette was still an Austrian princess and Rohan was the French ambassador there. Since his return to France in 1774, the cardinal had sought to regain the favor of Marie Antoinette, who had now become queen. Jeanne used his naivety and gullibility to convince him that she had a close and friendly relationship with the queen and that she could induce her to return to the cardinal. The countess hired an old comrade of her husband, Marc-Antoine Rétaux de Villette, who wrote false letters on her behalf, allegedly addressed to the cardinal by Marie Antoinette. Since the beginning of 1784, she successfully played to him that the Queen was conciliatory and was able to persuade the Grand Almosenier on several occasions on behalf of Marie Antoinette to spend large sums of money for allegedly charitable purposes. With the tricked money she financed herself and her husband a luxurious lifestyle and the purchase of her own house in Bar-sur-Aube for 18,000 livres. When Jeanne's web of lies became too unbelievable even for Rohan and he wanted to make sure of the whole thing, he demanded an audience with the Queen, which Jeanne should bring about for him as her intimate friend. The swindler therefore arranged a nightly meeting in August 1784 in one of the bosquets in the palace gardens of Versailles , at which a young woman named Marie-Nicole Leguay, who had a certain resemblance to the French queen and called herself Baronne d'Oliva, who The role of a veiled Marie Antoinette mimed. The cardinal actually fell for the farce , and Jeanne was able to convince Louis René Édouard de Rohan-Guéméné that the Queen wanted him to purchase a diamond necklace in her name that had been in vain for several years from the two Parisian jewelers Charles Böhmer and Paul Bassenge for the proud price of 1.8 million livres. Rohan did not suspect and agreed with the two jewelers a final price of 1.6 million livres, which were to be paid in four installments starting on July 31, 1785. The jewelers were also initially fooled by forged letters and actually believed that Cardinal Rohan was acting on behalf of Marie Antoinette. They handed him the valuable piece of jewelery on February 1, 1785, and he handed it to Jeanne de Saint-Rémy by return mail. Together with her husband, she broke the precious diamonds from their settings in the necklace and damaged many of the stones because no suitable tools were available. First attempts to sell some of the precious items in Paris failed because the jewelers to whom they were offered immediately believed that they were stolen goods and therefore refused to buy them. However, since no jewelry theft of this magnitude had been reported, Jeanne and her husband remained unmolested for the time being. In order to cash in on the booty, Nicolas de La Motte traveled to London in April 1785 and sold most of the diamonds in the English capital. Meanwhile in Paris, Jeanne used some stones to pay off debts with creditors and to pay suppliers. In total, the couple received 600,000 livres in exchange for their stolen property.

Trial, imprisonment and escape

When the fraud was discovered, Louis XVI. arrest the Grand Almosenier as the alleged main person in the affair on August 15, 1785 and bring him to the Bastille . Shortly afterwards, on August 18th, Jeanne was arrested. She was staying in her house in Bar-sur-Aube and was also transferred to the Bastille on August 20th. All of their property has been confiscated . Nicolas de La Motte was able to flee to England before being arrested, but Jeanne's accomplices Marc-Antoine Rétaux de Villette and Mademoiselle d'Oliva were also arrested. In a sensational trial before the Paris Parliament in May 1786, Jeanne denied any involvement in the fraud to the end and accused Rohan and Alessandro Cagliostro of being the masterminds. She claimed not to have anything to do with the matter, or to have known about it. Her defense letter Mémoire pour dame Jeanne de St Rémy de Valois , which she wrote together with her lawyer Jacques-François Doillot and which was the first of all the defendants to have published in early December 1785, was very popular. Such publications were actually to be had for free, but the Mémoire was in such demand that it was sometimes sold at exorbitant prices by those who could get hold of a copy. Jeanne's statements and allegations in it were so implausible that they exonerated Rohan more than they did. The judgment of May 31, 1786 absolved the cardinal of all charges, but Jeanne was hit much harder as the accused. The judges determined that they are using the Staupbesen publicly flogged by the executioners on both shoulders with a V for voleuse (German: thief) should be branded and then serving a life sentence in the Salpêtrière. In addition, all copies of their published justifications should be destroyed. After the verdict was announced, Jeanne tried unsuccessfully to commit suicide in the conciergerie , where she had been transferred on May 29th.

The sentence was carried out on June 21, shortly after five in the morning in the courtyard of the conciergerie. Because of the early hour, there were only a few onlookers present. Jeanne defended herself like a madwoman. It took four grown men to hold her, but the young woman resisted so much that the hangman slipped the branding iron and it was not her shoulder but her chest that was branded. Jeanne lost consciousness during the ordeal and was brought to the Salpêtrière passed out.

A fellow prisoner of Jeanne informed her in the course of 1786 that well-meaning people were in the process of organizing their escape from prison. It is possible that Jean-François Georgel , Cardinal Rohan's secretary, was the organizer behind these plans for liberation. Together with a fellow prisoner named Marianne, Jeanne de Saint-Rémy actually managed to break out of the Salpêtrière in June 1786 disguised as a man. Her escape route took her via Provins , Troyes , Nancy , Lunéville, Metz and Thionville to Olerisse in Luxembourg . From there she went on via Bruges and Ostend into exile to London, where she arrived on August 4, 1787. The backers who planned and organized their escape have remained unknown to this day.

English exile

In London she met her husband again, who had already squandered and gambled away all the proceeds from the sale of the stolen diamonds. The reunion of the couple was not particularly idyllic, because Nicolas de La Motte had meanwhile got used to living alone and felt little desire to live with his charming wife again. Above all, he hated the numerous hysterical scenes she made him.

Jeanne wrote her memoirs in collaboration with a Mr. Serre de La Tour, the first part of which, entitled Mémoire justificatif de la comtesse de Valois de la Motte , appeared in London in 1789 and was translated into German and English that same year. In the publication, she stamped Marie Antoinette and Cagliostro as confidants of the collar affair and accused the Queen of having secretly met Louis René Édouard de Rohan-Guéméné several times. The erotic relationship between the two should prove transcripts of 32 letters that Jeanne added to her memoir. She also claimed that Louis Auguste Le Tonnelier de Breteuil had been secretly pulling the strings the entire time. However, her work contained obvious falsehoods and contradictions to accounts she had previously given. Nevertheless, a sequel came out in 1789 with Second mémoire justificatif de la comtesse de Valois de la Motte, écrit par elle-même . A short time later, the La Motte couple separated and Nicolas returned to France in August of that year. A second edition of the first part of the memoir was also published in 1789.

The French royal family, whose reputation among the people had been enormously damaged by the collar affair, tried in advance to prevent the publication of the memoirs. The Queen sent her confidante, Marie-Louise of Savoyen-Carignan , Princess of Lamballe, and the Abbé de Vermond to London to dissuade Jeanne from the publication with a hush of 200,000 livres. The princess's efforts, however, were in vain. The exile took the money, but this did not prevent her from publishing it.

After Jeanne de Saint-Remy another from exile in 1789 polemic had brought that rather than a directed against Marie Antoinette because of their choice of words pamphlet was seen, appeared in 1792 in Paris her two-volume autobiography Vie de Jeanne de St Remy de Valois, ci devant comtesse de la Motte… écrite par elle-même , in whose foreword she exposed a petition published in her name in 1790 with the title Adresse de la comtesse de la Motte à l'Assemblée Nationale pour être déclarée citoyenne active as a forgery that did not was written by her. To prevent the spread of the plant in the capital, the king on May 5, 1792, all copies of the book by Arnaud de Laporte , intendant de la liste civile du roi , buy up to 14,000 livres and in the May 26 kilns of the royal Burn the porcelain factory in Sèvres . However, this could not prevent a second edition from being printed on the basis of an undestroyed copy, which found enormous sales in Paris. The biography was just as successful as Jeannes Mémoires justificatifs and was translated into English in the same year.

Jeanne de Saint-Rémy died at the age of 35 on August 23, 1791 at 11 o'clock in the evening in London as a result of falling out of a window. A few weeks earlier she had attempted to escape from the English police officers who had come to her on behalf of a creditor by a daring leap from the second floor. Among other things, she had broken both legs and her pelvis. After much agony, she succumbed to her severe injuries and was buried on August 26th in the cemetery of the parish church of Lambeth St Mary .

reception

Polemic pamphlets and pamphlets

Even during her lifetime, Jeanne de Saint-Rémys and her life story were included in contemporary publications, especially because the anti-royalist movement tried to exploit the collar affair and the associated loss of reputation of the French royal family. Until the 1790s, Countess La Motte was a recurring figure in pamphlets depicting her as an innocent victim of malicious political intrigue who unjustly had to answer for the excesses of the Queen and her favorite Madame de Polignac. Such publications include both Supplique à la Nation et requête à l'Assemblée nationale par Jeanne de Saint-Rémi de Valois ... en revision de son proces and Adresse de la comtesse de la Motte à l'Assemblée Nationale pour être déclarée citoyenne active , both of which appeared in 1790. But even if the titles suggest otherwise, Jeanne was no more the author of these publications than she wrote Conversation entre Madame de La Motte or Conference entre Madame de Polignac et Madame de La Motte . As early as 1789, the book La rein dévoilée ou supplément au mémoire de Madame la comtesse de La Motte, published in London, portrayed Jeanne as a whipping boy who had to answer for the queen's sexual debauchery. It tied in seamlessly with the allegations made in Jeanne's memoirs against Marie-Antoinette and Cardinal Rohan. Even revolutionaries took over the story of Countess La Motte by planning the resumption and revision of Jeanne's trial, which would expose the queen's deep involvement in the affair - and thus her guilt.

Fiction

The memoirs of her accomplice Marc-Antoine Rétaux de Villette, who wrote the Mémoires historiques des intringues de la cour, et de ce qui s'est passé entre la Reine, madame de Lamotte et in Venice in 1790, painted a more differentiated, albeit not necessarily true, picture of Jeanne published le comte d'Artois . The same applies to the memoirs of her husband Marc Antoine Nicolas de La Motte with the title Affaire du collier: Mémoires inédits du comte de Lamotte-Valois sur sa vie et son époque (1754-1830) , which Louis only after his death in 1858 in Paris Lacour were released. For example, there is talk of Jeanne's several suicide attempts.

The figure Jeanne de Saint-Rémys can also be found in various publications in later times, mainly because she was one of the main participants in the collar affair and this was widely received in many cultural areas. Alexandre Dumas published his novel The Queen's Collar in 1849 (original title Le Collier de la reine ). In it he processed the material in fictional form, because in his story it is not Jeanne but Cagliostro who pulls the mastermind behind the fraud, but the work comes up with many historical references.

Only gradually did the portrayal of Jeanne's person change from an innocent victim to a more realistic image of an extremely ambitious woman who did not shrink from cunning deception in order to achieve her goal. Frantz Funck-Brentano endeavored at the beginning of the 20th century in his publications L'affaire du collier; d'après de nouveaux documents and La morte de la Reine (Les suites de l'affaire du collier) d'après de nouveaux documents , to paint a picture of Countess La Motte as neutral as possible, by not only referring to the potentially tendentious memoirs was supported by contemporaries, but also used archival material that had not been evaluated until then, such as correspondence and memos. Even in the 21st century, his two works are still often the basis for publications on the collar affair and the life of Jeanne de Saint-Rémys.

Some recent publications take the Countess very harshly to justice. Joan Haslip characterized her in 1987 in her biography Marie Antoinette as "a woman consumed by ambition and hatred, who knew neither gratitude for her benefactors nor sympathy for the victims of her deceit." Marie Antoinette monograph . The unfortunate queen from 1988, on the other hand, is a little more flattering.

Stage and film

Even Johann Wolfgang von Goethe used in his 1791 comedy The Great Cophta motifs from the history of Jeanne, the only in his play Marquise is called. Also in Arno Nadel's play Cagliostro. Jeanne de Saint-Rémy finds its place in the drama in five acts from 1913, as well as in Edmund Nick's work The Queen's Collar. Operetta in three acts , which at the Bavarian State Operetta in on December 1, 1948 Munich premiere celebrated.

From October 1979, Nippon TV aired the 40-part anime Lady Oscar , which was based on Riyoko Ikeda's successful manga The Roses of Versailles . Countess La Motte appears in some episodes as a participant in the collar affair. The television series was subsequently also broadcast in Europe, Latin America and the Arab world. The picture of the ambitious young woman, who grew up with her half-sister at a poor seamstress, has very little in common with the real role model.

As early as 1929, Gaston Ravel and Tony Lekain produced the first film adaptation of Dumas' novel, Le Collier de la reine . The role of Jeanne de la Motte was played by Marcelle Chantal before Marcel L'Herbier released the same subject in 1946 under the title L'Affaire du collier de la reine with Viviane Romance as Jeanne. In 2001, the American director Charles Shyer delivered The Queen's Collar, the last movie to date, of which Jeanne St. Remy de Valois is the protagonist . The script, written by John Sweet , stuck rudimentarily to the historical model, but deviated from it in many details. The Lexicon of International Films described the lead role, portrayed by Hilary Swank , as a person who "[...] was essentially a cunning schemer of highly dubious reputation."

Fonts

- Mémoire pour Dame Jeanne de Saint-Remy de Valois, Épouse du Comte de La Motte , (Cellot), Paris 1785

- Mémoire (s) justificatif (s) de la comtesse de Valois de la Motte, écrit par elle-même , London 1789.

- Second Mémoire justificatif de la comtesse de Valois de la Motte, écrit par elle-même , London 1789

- Lettre de la Ctesse Valois de la Motte à la Reine de France , Oxford (1789)

- Vie de Jeanne de St. Remy de Valois, ci-devant comtesse de la Motte… écrite par elle-même , 2 volumes, Paris Year I of the Republic (= 1792)

literature

- Émile Campardon: Marie-Antoinette et le procès du collier, d'après la procédure instruite devant le Parlement de Paris . Plon, Paris 1863 ( online ).

- Frantz Funck-Brentano: L'affaire du collier; d'apres de nouveaux documents . Hachette, Paris 1901 ( online ).

- Frantz Funck-Brentano: La morte de la Reine (Les suites de l'affaire du collier) d'après de nouveaux documents. Hachette, Paris 1901 ( online ).

- Joan Haslip: Marie Antoinette. A tragic life in stormy times. Piper, Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-492-24573-9 , pp. 230-248.

- Louis Hastier: La vérité sur l'affaire de collier . 3. Edition. Fayard, Paris 1955.

- Alexander Lernet-Holenia : The Queen's Collar. Paul Zsolnay, Vienna / Hamburg 1962.

- Évelyne Lever: L'affaire du collier . Fayard, Paris 2004, ISBN 2-213-62079-2 .

- L. Louvet: La Motte (Jeanne de Luz, de Saint-Remy, de Valois, comtesse de.) In: Jean Chrétien Ferdinand Hoefer : Nouvelle biographie générale depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à nos jours. Volume 29. Firmin Didot, Paris 1861, Sp. 267-273 ( online ).

- William Rutherford Hayes Trowbridge: Seven splendid sinners. T. Fisher Unwin, London 1910, pp. 207-261 ( online ).

- Raoul Vèze: Mémoires de la comtesse de la Motte-Valois (Affaire du collier de la Reine). Bibliothèque des curieux, Paris 1911 ( online ).

Web links

- Digitized by Mémoire pour Dame Jeanne de Saint-Remy de Valois, Épouse du Comte de La Motte

- Digitized from Mémoires justificatifs de la comtesse de Valois de la Motte, écrits par elle-même

- Digitized by Vie de Jeanne de St. Remy de Valois, ci-devant comtesse de la Motte ... écrite par elle-même : Volume 1 and Volume 2

- Digitization of the trial judgment and a summary of the incidents

Individual references and comments

- ↑ A. Lernet-Holenia: The Queen's Collar , p. 13.

- ^ WRH Trowbridge: Seven splendid sinners , p. 213.

- ↑ É. Lever: L'affaire du collier , p. 73.

- ↑ L. Hastier: La vérité sur l'affaire de collier , S. 138th

- ↑ É. Campardon: Marie-Antoinette et le procès du collier, d'après la procédure instruite devant le Parlement de Paris , p. 23.

- ↑ The pension for the two sisters was 800 livres.

- ↑ É. Lever: L'affaire du collier , p. 74.

- ^ Stefan Zweig: Marie Antoinette. Portrait of a medium character . S. Fischer, [Frankfurt a. M.] 1961, p. 168.

- ^ WRH Trowbridge: Seven splendid sinners , p. 218.

- ↑ É. Campardon: Marie-Antoinette et le procès du collier, d'après la procédure instruite devant le Parlement de Paris , p. 179.

- ↑ É. Campardon: Marie-Antoinette et le procès du collier, d'après la procédure instruite devant le Parlement de Paris , p. 273.

- ↑ J. Haslip: Marie Antoinette , p. 231.

- ↑ É. Lever: L'affaire du collier , p. 77.

- ↑ É. Campardon: Marie-Antoinette et le procès du collier, d'après la procédure instruite devant le Parlement de Paris , p. 56.

- ↑ L. Hastier: La vérité sur l'affaire de collier , p. 146.

- ↑ É. Campardon: Marie-Antoinette et le procès du collier, d'après la procédure instruite devant le Parlement de Paris , p. 57.

- ↑ A. Lernet-Holenia: The Queen's Collar , p. 56.

- ↑ J. Haslip: Marie Antoinette , p. 232.

- ^ Évelyne Lever: Marie Antoinette. The biography . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-491-96126-2 , p. 292.

- ↑ a b L. Louvet: La Motte (Jeanne de Luz, de Saint-Remy, de Valois, comtesse de) , Col. 269.

- ^ Évelyne Lever: Marie Antoinette. The biography . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-491-96126-2 , p. 293.

- ↑ É. Lever: L'affaire du collier , p. 105.

- ^ Évelyne Lever: Marie Antoinette. The biography . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-491-96126-2 , p. 284.

- ^ Évelyne Lever: Marie Antoinette. The biography . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-491-96126-2 , p. 285.

- ^ Évelyne Lever: Marie Antoinette. The biography . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-491-96126-2 , pp. 285-286.

- ↑ É. Lever: L'affaire du collier , p. 126.

- ↑ É. Lever: L'affaire du collier , p. 141.

- ^ Hermann Schreiber: Marie Antoinette. The unfortunate queen . List, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-471-78745-3 , p. 125.

- ↑ L. Hastier: La vérité sur l'affaire de collier , p. 301.

- ↑ É. Lever: L'affaire du collier , p. 291.

- ^ WRH Trowbridge: Seven splendid sinners , p. 251.

- ^ A b Hermann Schreiber: Marie Antoinette. The unfortunate queen . List, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-471-78745-3 , p. 128.

- ↑ É. Campardon: Marie-Antoinette et le procès du collier, d'après la procédure instruite devant le Parlement de Paris , p. 180.

- ^ F. Funck-Brentano: La morte de la Reine , p. 29.

- ↑ In some older publications one finds the claim that Charles Alexandre de Calonne , the controller- general of finances, who fell from grace in 1787 and was dismissed by the king, edited Jeanne's memoirs. All he did was to send a preliminary manuscript, which he had annotated, to the French queen. See É. Lever: L'affaire du collier , p. 306.

- ↑ Klaus H. Kiefer: “The famous witch epoch” (= Ancien régime, Enlightenment and Revolution , Volume 36). Oldenbourg, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-486-20013-5 , pp. 67-68 ( online ).

- ^ F. Funck-Brentano: La morte de la Reine , p. 123.

- ^ Stefan Zweig: Marie Antoinette. Portrait of a medium character . S. Fischer, [Frankfurt a. M.] 1961, p. 194.

- ^ WRH Trowbridge: Seven splendid sinners , p. 256.

- ↑ É. Lever: L'affaire du collier , p. 316.

- ^ F. Funck-Brentano: La morte de la Reine , p. 162.

- ^ F. Funck-Brentano: La morte de la Reine , p. 163.

- ^ A b Sarah C. Maza: Private Lives and Public Affairs. The Causes Célèbres of Prerevolutionary France . University of California Press, Berkeley et al. 1995, ISBN 0-520-20163-9 , p. 207 ( online ).

- ↑ É. Campardon: Marie-Antoinette et le procès du collier, d'après la procédure instruite devant le Parlement de Paris , pp. 164–165.

- ^ F. Funck-Brentano: La morte de la Reine , pp. 111-112.

- ↑ J. Haslip: Marie Antoinette , p. 230.

- ↑ Jeanne de Saint-Rémy. In: Lexicon of International Films . Film service , accessed June 4, 2021 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Saint-Rémy, Jeanne de |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Valois de Saint-Rémy, Jeanne de; La Motte, Jeanne de; La Motte-Valois, Jeanne de; Luz de Saint-Rémy, Jeanne de; Lamotte, Jeanne de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French nobleman and mastermind of the collar affair |

| BIRTH DATE | July 22, 1756 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Fontette |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 23, 1791 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | London |