Dark Tiger Python

| Dark Tiger Python | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dark Tiger Python in Kaeng Krachan National Park |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Python bivittatus | ||||||||||||

| Kuhl , 1820 |

The dark tiger python ( Python bivittatus ) is a species of snake from the family of the pythons (Pythonidae) and is there in the genus of the actual pythons ( python ). With secured lengths of over five meters, it is one of the largest snakes in the world. The distribution area covers large parts of tropical Southeast Asia . The species lives there in a wide range of forested habitats not too far from water and at least occasionally also on the edge of human settlements. For several decades, a population established by illegal reintroductions has also established itself in Florida.

Depending on the size of the pythons, the food consists of small to medium-sized, very rarely large vertebrates, up to adolescent pig deer and adult leopards . Tiger pythons, like all species of the genus Python, lay eggs (oviparous) and belong to the species in which the females can significantly increase the incubation temperature through muscle tremors. The dark tiger python is listed by the IUCN as endangered ("Vulnerable") due to its endangerment through direct pursuit and habitat destruction .

features

Wild mainland dark tiger pythons usually reach a total length of 3.7 meters. Animals larger than 4 meters are rare, those of 5 meters are exceptional. The longest ever seriously measured dark tiger python was a female named "Baby" who lived in a private zoo in Gurnee, Illinois , for 27 years . After his death, a total length of 5.74 m (18 ft 10 in) was determined. Information on much larger specimens has so far not withstood a scientific review.

Dark tiger pythons from the Indonesian islands of Java , Bali and Sulawesi are much smaller ( island dwarfing ). In Bali, the total length of adult animals averages 2 meters; the animals on Sulawesi reach a maximum total length of 2.4 meters.

The dark tiger python generally has a darker pattern than the light tiger python. Its basic color ranges from light brown, yellowish to greyish. In animals from the mainland, the dark brown to reddish brown saddle spots are usually rectangular in shape and bordered in black. The wide, rectangular flank patches are brown or greenish-brown in color and have a black border. Flank spots and the side edges of the saddle spots are also surrounded by a light recess. The ventral side is white-yellow. Characteristically, the large, arrowhead-shaped, brown pattern on the top of the head is clearly pronounced. Most of the time its tip extends to the tip of the snout. The tongue of this subspecies is blue-black.

The Sulawesian population has a slightly different pattern. These animals often show very irregularly shaped, partially dismembered and staggered saddle spots that can contain ocels. Characteristically, the saddle spots are also completely surrounded by a clear, bright recess. The flank spots of this population are also partially ocellated, which is otherwise atypical for the dark tiger python.

anatomy

Juvenile animals are quite slim, but adult tiger pythons have a very strong body. There is a clear sexual dimorphism with regard to body length and weight : females are on average considerably larger and heavier than males. The head is massive, almost twice as long as it is wide and moderately set off from the neck. The lateral arrangement of the eyes results in a field of view of 135 °.

Scaling

The nostrils are arranged dorsally and each surrounded by a large nasal scale. The nasals (nasal shields) are separated from each other by a pair of small but clearly recognizable internasals (intermediate nasal shields) . These are in turn bordered by rectangular prefrontalia (forehead shields). A second, much smaller pair of prefrontalia, which is often divided into several small scales, lies between the anterior prefrontalia and the very similarly shaped paired frontalia (frontal shields). Over the eyes is a large Supraoculare (via eye shield). The rostral (snout shield) has, like most other pythons, two deep labial pits .

On the sides of the head, the nasal scales are followed by several Lorealia (rein shields), which vary in size and appearance. Usually there are two preocularia (fore-eye shields) and three to four postocularia (posterior eye shields). The eye is separated from the 11 to 13 upper lip shields ( supralabialia ), of which the first and second deep labial pits bear, by a continuous row of lower eye shields ( subocularia ). Of the 16 to 18 infralabialia (lower lip shields ) several anterior and posterior labial pits are indistinct.

The number of ventralia (belly shields) varies depending on the origin of the individuals between 245 and 270, the number of dorsal rows of scales in the middle of the body between 58 and 73. The number of paired subcaudalia (tail underside shields) is 57 to 83. The anal (anal shield) is undivided.

coloring

The light basic color of the dark tiger python becomes paler towards the flanks. 30 to 38 large, often rectangular, dark saddle spots run across the back. On the flanks, alternating with the pattern on the back, there are large dark spots that are shaped specifically for the subspecies. The light belly side is darkly speckled towards the tail. On the side of the head, a dark, tapering band runs from the eye towards the nose. A wider, black bordered band runs from the eye to the corner of the mouth. This, together with a wedge-shaped dark spot below the eye, encloses a white area. An arrowhead-shaped brown pattern with a light point in the middle runs from the nose to the eyes to the nape of the neck. The color intensity of the arrow drawing is subspecies-specific.

Systematics

The dark tiger python was first described in 1820 by the German naturalist Heinrich Kuhl . The inner systematics of the tiger pythons was controversial for about 200 years. For a long time the dark tiger python was considered a subspecies of the light tiger python ( Python molurus ). The distribution areas of the two forms certainly overlap in northeast India, Nepal, western Bhutan, southwest Bangladesh and possibly also in northwest Burma. Previous observations in India and Nepal show that, contrary to previous assumptions , the two species, when they occur sympatric , inhabit different, sometimes even the same habitats and do not mate with one another. In 2009, Jacobs and colleagues therefore suggested that the two forms should be given species status based on the two characteristic morphological differences in scaling and patterning of the top of the head. The separation into two types has now also been carried out in the Reptile Database , a scientific online database on the taxonomy of reptiles.

On the Indonesian islands of Bali, Sulawesi, Sumbawa and Java, certain animal geographic and morphological aspects speak in favor of a differentiation from Python bivittatus . These populations are more than 700 kilometers apart from the animals of the mainland, show differences in pattern and have developed dwarf forms on Sulawesi, Bali and Java. In 2009 animals from Sulawesi were identified by Jacobs et al. examined in more detail for the first time. Due to differences in size and color, the authors suggest delineating this dwarf form as a separate subspecies; they suggest P. bivittatus progschai as a scientific name . Molecular genetic studies on the status of this dwarf form are still pending. How far the other Indonesian island populations differ from the mainland form is also still unclear.

Within the authentics pythons the Dark and the Light Burmese Python is after a molecular genetic study next to the Northern Rock Python and Southern rock python related. This is the result of a recent molecular genetic study that includes the northern rock python and the light tiger python.

distribution

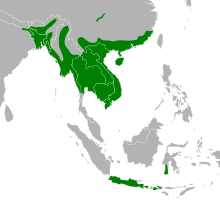

The distribution of the dark tiger python ranges from northeast India, Nepal , western Bhutan , southeast Bangladesh via Burma , Thailand , Cambodia , Laos , the northern part of the Malay Peninsula , Vietnam to southern China including Hainan and a northern, isolated population in the Sichuan Basin . Further south it is missing in the south of the Malay Peninsula and on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra . Only after this striking distribution gap does its occurrence extend to the island of Java , the southwest of Sulawesi ( Sulawesi Selatan ) and the small Sunda islands of Bali and Sumbawa .

In north-east India, Nepal, west Bhutan, south-west Bangladesh and possibly also in north-west Burma, the distribution areas of dark and light tiger pythons overlap. Here they live in neighboring habitats, in some places even the same. In Bangladesh, the dark tiger python seems to occur particularly along the Brahmaputra . In India and Nepal, which are dominated by the light tiger python, populations of the dark tiger python have only recently been discovered: In Nepal, namely in the Bardia National Park - and in the Chitwan National Park , as well as in the Sagarmatha zone . The latter goes south into the Indian east of Bihar . In India, the dark tiger python can also be found in the Corbett National Park and in the Bhitarkanika National Park and in South Kolkata . How large the distribution areas of the dark species there are and whether they are perhaps partially connected is not yet known.

A population of the dark tiger python has been established in the Florida Everglades since 1979 through illegal reintroduction of terrarium animals .

habitat

Dark Tiger Pythons colonize a wide range of habitats, including rainforest , monsoon forest , mountain forest , mangrove forest , marshland , coastal plains and grassland . The prerequisite is always proximity to the water. Most of the deposits are below 200 meters above sea level. In the Tam Dao Mountains in Vietnam it can also be found at 1200 meters and in the few climatically mild rhododendron and bamboo forests of Nepal up to 2000 meters above sea level.

In northeastern India, where the two species coexist very closely, the light tiger python is found in dry forests and in arid , sandy areas, while the dark tiger python inhabits moist grasslands crossed by rivers. Compared to the reticulated python , which partly lives in the same areas in Southeast Asia, the demands of the dark tiger python on direct moisture in the environment are significantly lower. In the vicinity and on agricultural land, however, it repeatedly hunts rodents. The species was also found sporadically in populated areas in Hong Kong and Thailand. In Bali, the tiger python even lives around the city of Gilimanuk. Here it populates gardens and backyards and occasionally preyes on domestic chickens.

Way of life

behavior

Despite its huge distribution area and its abundance in some areas of the area, little is known about the behavior of this python. The dark tiger python is a mainly ground-dwelling snake that moves slowly and in a straight line on the ground. As a slow, good climber, he often stays in the branches of bushes and trees in order to stalk prey well camouflaged. They lead a semi-aquatic life in areas with lakes, rivers and other bodies of water. They move much faster and more nimbly in water than on land. When swimming, their body is completely submerged in the water, with the exception of the tip of the snout. They often lie partially or completely submerged on the shallow bank for hours. They remain completely under water for up to half an hour without drawing air, or only the nostrils protrude above the water surface. Dark Tiger Pythons are predominantly crepuscular and nocturnal. However, the daily activity is closely related to the ambient temperature.

Younger Tiger Pythons are particularly active in search of prey. There are sometimes several kilometers between the hiding place and the hunting ground. A female dark tiger python with a total length of 2.7 meters was monitored by tracking devices for 24 days. During this period, a phase with an extensive search for food, a period of limited movement during digestion and a return to the prey-seeking behavior were recorded. For all of this, this snake claimed an area of 12.3 hectares and covered significantly more than 2.5 kilometers in it.

Very large dark tiger pythons seem to move less outside of the mating season. They usually settle in ideal, prey rich territory with good hiding places. Tracking transmitters in the Everglades were able to show that adult males looking for a partner cover long distances during the mating season. Sexually mature females remain much more stationary on average. In search of a suitable habitat, adult tiger pythons of both sexes are able to cover distances of 60 kilometers via water and land at top speeds of more than 2.3 kilometers per day within 2.5 months.

There are also still considerable gaps in knowledge about the social behavior of the species.

food

The prey spectrum ranges from mammals and birds to cold-blooded lizards and amphibians: frogs , toads , monitor lizards , bats , flying foxes , deer piglets , civet cats and numerous rodents are eaten. He also catches water birds , waders and hens . The size of the prey correlates with the size of the tiger python. Exceptionally, prey up to the size of small monkeys , wild boar piglets, adolescent pig deer and horse deer fawns has been recorded for large specimens . However, horns that are too large represent an obstacle to swallowing and harbor the risk of internal injuries.

Systematic studies on the composition of the prey spectrum have apparently not yet been published. Ernst & Zug name mammals as their predominant prey. The diet is probably adapted to the prey repertoire of the respective habitat and to annual fluctuations due to rodent migration and bird migration .

As an ambulance hunter, he prefers to hide his prey, in the branches or in the water. Once the Tiger Python has recognized a prey, it moves slowly towards it and often wiggles its tail in a species-typical manner. The victim is then packed a flash, embraced and for constrictors suffocated typical grip. Depending on the size of the prey, the subsequent devouring can take several hours. While small prey is often digested within a week, a dark tiger python with a total length of over 5 meters in the Berlin Zoo needed 23 days for a pig weighing 25 kilograms.

Laboratory tests on juvenile dark tiger pythons have shown that the heart muscle can enlarge by up to 40% when a large food animal is digested. The maximum enlargement of the heart cells ( hypertrophy ) is achieved after 48 hours due to the increased incorporation of contractile proteins into muscle fibrils . This effect contributes to an energetically more favorable, increased cardiac output , which allows digestion to proceed faster. The digestive tract also adapts to the digestive system. Two days after feeding, the mucous membrane of the small intestine grows up to three times as much. After about a week it will shrink back to its normal size. Up to 35% of the energy absorbed with the prey is required for the entire digestive process.

Reproduction

Very little is known about reproduction in the field either. The willingness of the female to mate is signaled to the male by a brown, liquid sex attractant ( pheromone ) from the cloaca. After a period of pursuit and rapprochement, the male crawls over his partner, presses his head against her and begins to scratch her with his anal spurs. The stimulated female lifts her tail. Now the male Tiger Python can introduce one of its double-lobed, flattened hemipenisse into the female's cloaca .

Nothing is known from nature about the interactions between males during the mating season. In captivity, male Tiger Pythons sometimes become territorial and fight commentary with rivals . If two competitors meet, they flinch at each other at first, then begin to crawl next to each other, stand up with the front third, climb up against each other and try to push the opponent to the ground. If there is no submission, there will be violent scratching with the anal spurs and finally violent biting.

The soft-shelled, white eggs measure 74–125 × 50–66 millimeters and weigh 140–270 grams. The eggs that stick together are surrounded and protected by the female. The loop arrangement regulates moisture and heat. In addition, the female Tiger Python is capable of trembling muscles. This allows incubation in colder regions while maintaining the optimal incubation temperature around 30.5 ° C. As a rule, the female does not eat any food or leave the nest during the incubation period.

Hatchlings appear in south-west Burma as early as June, so the breeding season starts earlier here. The newly hatched young animals that are now left to their own devices have a total length of between 40 and 60 centimeters and weigh 80 to 150 grams in most of the distribution area. However, hatchlings of the Sulawesian dwarf form are only 30 to 35 centimeters. Tiger pythons reach sexual maturity at around three years of age.

In the Artis Zoo in Amsterdam , a female dark tiger python laid vital eggs for five consecutive years in the permanent absence of males. A DNA analysis of the purely female offspring revealed that their genetic makeup is identical to that of the mother. The young animals were consequently not created through fertilization, but through parthenogenesis (virgin generation). This is rare in reptiles and so far unknown in other giant snake species.

Age and life expectancy

Information on the average and maximum ages of individuals living in the wild is unknown. However, tiger pythons are believed to live to be more than 30 years old in nature under favorable conditions. The average age in captivity is 25 years. The record is 34 years.

Natural enemies

Apart from humans, the tiger python has many enemies, especially in its youth. These include, for example, king cobras , mongooses , big cats such as tigers and leopards, bears , various owls and some birds of prey such as the black kite . The Bengal monitor ( Varanus bengalensis ) is one of the nest predators .

Endangerment and population status

The commercial exploitation of the Tiger Python for the leather industry has caused a significant population decline in numerous countries in its area of distribution.

In Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, the tiger python was still widespread and relatively common in the 1970s. The use of the species for the leather industry grew massively in the following years and in 1985 reached a peak of 189,068 hides officially exported from these countries. The international trade in live Tiger Pythons also peaked this year with 25,000 animals. In 1985, a trade restriction was issued in Thailand to protect the tiger pythons, which means that only 20,000 hides may be exported annually. There was also considerable illegal trade. In 1990 tiger python skins from Thailand were on average only 2 meters long, a clear sign that the number of reproductive animals must be massively decimated. By 2003, Tiger Pythons are said to have become more common again in some parts of Thailand. In Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, the leather industry is still significant today and is a major contributor to the ongoing population decline.

The trade in tiger python skins and their gall bladders also flourished in Indonesia for decades. This led to a threatening decline in the number of snakes, which are already rare there. In 1978 the government acted and placed the tiger python under protection. Since then, practically no export permits have been issued.

Certain tribes in northern Thailand, Laos and Cambodia but also Burmese, Karen , Chinese and small ethnic groups in Indonesia hunt the tiger python for its meat. In China, eggs are also considered a delicacy, the liver and heart are a stimulant, the gall bladder is used for medicinal purposes and the skin is a raw material for musical instruments and handicrafts. Continuous consumption is a serious threat, especially for the tiger python population in China, which has declined significantly for more than a century. In Burma, too, where the tiger python was described as "occurring in abundance" in 1912, intensive use as a source of food has caused a visible decimation.

Extensive clearing of forests, forest fires and soil erosion are an increasing problem in tiger python habitats. The increasing urban sprawl and agricultural expansion of a constantly growing population is also increasingly restricting its living space. All of this leads to shrinking, isolation and ultimately the extermination of individual populations.

Wild populations of the dark tiger python are in need of protection, are listed in Appendix II and are subject to export restrictions. The IUCN now lists the dark tiger python as endangered ("Vulnerable").

Tiger pythons as a neozoon

In the Everglades in the US state of Florida , dark tiger pythons were illegally released into the wild and have been able to establish themselves there since 1979. From 2001 in particular, there was a significant increase; in 2007 the number was estimated at around 30,500 animals. The animals are considered a threat to native fauna , e.g. B. for bobcats , opossum rats , grebes , snow ibis and cranes . Small to medium-sized Mississippi alligators are also part of the prey spectrum there. In a dead 3.86 meter long tiger python, for example, a 2.10 meter long alligator was found. On the other hand, smaller tiger pythons are also eaten by alligators.

Tiger python and human

Behavior towards people

Tiger pythons living in the wild are usually not very aggressive. If they are disturbed, they hiss warning or crawl away and try to hide. They only defend themselves with strong, painful defensive bites when they are seriously alarmed. Only a few animals are irritable quickly and start defending themselves from the start. This is especially true for single individuals from Sulawesi. Tiger pythons living in the wild have been repeatedly alleged to have killed humans. Mainly unsupervised babies and young children are said to have fallen victim in the range. However, there is no reliable evidence for this.

Confirmed deaths are known from the United States, where adults were sometimes suffocated by tiger pythons kept as pets. The reason for this was always negligent handling, which could trigger the hunting instinct in the pythons.

Cultural

Tiger python meat has been eaten in numerous countries in Southeast Asia for centuries. In addition, tiger python innards are very important , especially in traditional Chinese medicine . The leather industry is also a branch of the economy that should not be underestimated in some Southeast Asian countries, employing professional hunters, tanners and traders. Farmers who accidentally pick up a tiger python in their fields also receive an additional income. In addition, tiger python and reticulated python farms have been established in numerous Asian countries, especially in Southeast Asia, over the past 30 years. In addition to its main use in the leather industry, meat is also sold as a delicacy.

Most people in Southeast Asia do not fear the tiger python and treat them as a fellow creature. In some places these snakes are even welcome. Farmers are becoming increasingly aware that tiger pythons play an important role in eating rodents on agricultural land.

Tiger pythons have long been popular animals in Europe. In 1842, in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, a brooding female dark tiger python was used to study muscle tremors and the resulting increase in temperature. In the late 19th century, these imposing exotic species could not be missing in the menageries of numerous castles and parks. For a long time, these pythons were also used as an attraction in snake performances in circus and variety shows .

The tiger python is currently very popular with private owners in Europe and the USA. Despite its size, the dark tiger python is kept lively and reproduced in captivity thanks to its appealing drawing and rather calm temperament. Numerous color mutations of the dark tiger python have been bred. Also hybrids between Bright Tiger Python and Dark tiger python, Indian python and reticulated python , Indian python and python and Tiger Python and Rock Python are known from breeding in captivity.

Legal requirements for keeping

In order to ensure that Tiger Pythons, as potentially dangerous wild animals , are cared for appropriately and competently and do not pose a threat to the public, many countries have also created legal requirements for keeping them.

According to the Animal Welfare Ordinance of 2008, there are minimum requirements for keeping tiger pythons in Switzerland. The cantonal veterinary office issues holding permits and carries out periodic checks on keepers.

In Germany, eight federal states have a law to prevent very large giant snakes. The keeping of Tiger Pythons there is subject to approval.

In Austria, tiger python keeping is subject to mandatory reporting according to the Animal Welfare Act of 2004 (§ 25) and the 2nd Animal Husbandry Ordinance of 2004 minimum requirements. In addition, there are state-specific security police regulations. The private keeping of the dark tiger python or both subspecies is prohibited in certain federal states. In others, licensing requirements and random to periodic controls apply in some cases.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Python bivittatus in the Red List of Endangered Species of the IUCN 2012. Posted by: Stuart, B., Nguyen, TQ, Thy, N., Grismer, L., Chan-Ard, T., Iskandar, D., Golynsky , E. & Lau, MWN, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ↑ a b c S. M. Campden-Main: A field guide to the snakes of South Vietnam . City of Washington 1970, pp. 8-9.

- ^ MA Smith: Reptilia and Amphibia, Vol. III, Serpentes. In: The Fauna of British India, Ceylon and Burma, including the whole of the Indo-Chinese Sub-Region . Tailor and Frances, Ltd., London 1943, pp. 102-109.

- ^ A b H. Saint Girons: Les serpents du Cambodge . In: Mémoires du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle , Série A 1972, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ a b J. Deuve: du Laos Serpents . In: Mémoire ORSTOM No. 39, Paris 1970, pp. 61-62, 65-66.

- ^ DG Barker, SL Barten, JP Ehrsam, L. Daddono: The corrected lengths of two well-known giant pythons and the establishment of a new maximum length record for Burmese pythons, Python bivittatus. In: Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society , Volume 47, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-6 (pdf).

- ↑ a b c d e D. G. Barker, TM Barker: The Distribution of the Burmese Python, Python molurus bivittatus . (Compilation from various publications and expert opinions) In: Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society , Volume 43, Issue 3, 2008, pp. 33-38.

- ↑ a b c d e J. L. McKay: A field guide to the amphibians and reptiles of Bali . Krieger Publishing Company 2006, pp. 13, 14, 18, 86. ISBN 1-57524-190-0 .

- ↑ a b c d e H. J. Jacobs, M. Auliya, W. Böhme: On the Taxonomy of the Dark Tiger Python, Python molurus bivittatus KUHL, 1820, especially the population of Sulawesi - On the Taxonomy of the Burmese Python, Python molurus bivittatus KUHL, 1820 , specifically on the Sulawesi population. In: SAURIA, Volume 31, Issue 3, Berlin 2009, pp. 5-16.

- ^ A b R. Whitaker, A. Captain: Snakes of India, the field guide . Chennai, India: Draco Books 2004, pp. 3, 12, 78-81, ISBN 81-901873-0-9 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i J. G. Walls: The Living Pythons - A complete guide to the Pythons of the World . TFH Publications 1998, pp. 131-142. ISBN 0-7938-0467-1 .

- ↑ R. Bauchot (Ed.): Snakes - evolution, anatomy, physiology, ecology and distribution, behavior, threat, endangerment, keeping and care . Bechtermünz Verlag 1994, pp. 55, 181. ISBN 3-8289-1501-9 .

- ↑ a b c d e f M. O'Shea: Herpetological results of two short field excursions to the Royal Bardia region of western Nepal, including range extensions for Assamese / Indo-Chinese snake taxa . In: A. de Silva (Ed.): Biology and conservation of the amphibians, reptiles, and their habitats in South Asia. Proceedings of the International Conference on Biology and Conservation of Amphibians and Reptiles in South Asia, Sri Lanka , October 1996. Amphibia and Reptile Research Organization of Sri Lanka (ARROS), 1998, pp. 306-317, ISBN 955-8213-00- 4 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h H. Schleich, W. Kästle: Amphibians and Reptiles of Nepal-Biology, Systematics, Field Guide . ARG Gantner Verlag KG 2002, pp. 795-802. ISBN 978-3-904144-79-7 .

- ^ Kuhl, H. (1820). Python bivittatus mihi . Contributions to zoology and comparative anatomy. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag der Hermannschen Buchhandlung. p. 94.

- ^ A b c d M. O'Shea: Boas and Pythons of the World . New Holland Publishers 2007, pp. 80-87. ISBN 978-1-84537-544-7 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h B. Groombridge, L. Luxmoore: Pythons in South-East Asia - A review of distribution, status and trade in three selected species. Secretariat of CITES, Lausanne, Switzerland 1991. ISBN 2-88323-003-X .

- ^ Python bivittatus in The Reptile Database

- ^ Python molurus in The Reptile Database

- ↑ a b c R. de Lang, G. Vogel: The snakes of Sulawesi: A field guide to the land snakes of Sulawesi with identification keys . In: Frankfurt Contributions to Natural History , Volume 25, Edition Chimaira 2005, pp. 23-27, 198-201. ISBN 3-930612-85-2 .

- ↑ LH Rawlings, DL Rabosky, SC Donnellan, MN Hutchinson: Python phylogenetics: inference from morphology and mitochondrial DNA. In: Biological Journal of the Linnean Society , Volume 93, 2008, pp. 603-619 (PDF).

- ↑ a b c d R. W. Snow, KL Krysko, KM Enge, L. Oberhofer, A. Warren-Bradley, L. Wilkins: Introduced populations of Boa constrictor (Boidae) and Python molurus bivitattus (Pythonidae) in southern Florida. In RW Henderson, R. Powell: The Biology of Boas and Pythons . Eagle Mountain 2007, pp. 416-438. ISBN 0-9630537-0-1 .

- ↑ a b N. C. Goodyear: Python molorus bivittatus (Burmese python). Movements . Herpetological Review Volume 25, Issue 2, 1994, pp 71-72.

- ↑ a b O. SG Pauwels, P. David, C. Chimsunchart, K. Thirkakhupt: Reptiles of Phetchaburi Province, Western Thailand: a list of species, with natural history notes, and a discussion on the biogeography at the Isthmus of Kra. In: The Natural History Journal of Chulalongkorn University , Volume 3, Issue 1, 2003, pp 23-53.

- ↑ a b W. Auffenberg: The Bengal monitor . Gainesville, University Press of Florida 1994, pp. 210, 314, 405, 478.

- ^ RG Harvey, ML Brien, MS Cherkiss, M. Dorcas, M. Rochford, RW Snow, FJ Mazzotti: Burmese Pythons in South Florida - Scientific Support for Invasive Species Management. University of Florida, April 2008, IFAS Publication Number WEC-242 (online, pdf).

- ^ CH Ernst, GR Zug: Snakes in Question . Washington DC. and London: Smithsonian Institution Press 1996, pp. 91-169. Quoted in: RW Snow, M. Brien, MS Cherkiss, L. Wilkins, FJ Mazzotti: Dietary habits of the Burmese python, Python molurus bivittatus, in Everglades National Park, Florida . In: British Herpetological Society: Herpetological Bulletin , No. 101, Autumn 2007, p 6. ISSN 1473-0928 .

- ↑ a b R. W. Snow, M. Brien, MS Cherkiss, L. Wilkins, FJ Mazzotti: Dietary habits of the Burmese python, Python molurus bivittatus, in Everglades National Park, Florida. In: Herpetological Bulletin , Volume 101, 2007, pp. 5-7. ISSN 1473-0928 .

- ^ CH Pope: The giant snakes: the natural history of the boa constrictor, the anaconda, and the largest pythons, including comparative facts about other snakes and basic information on reptiles in general . Routledge and Kegan, London 1962, pp. 93, 140-147.

- ↑ H.-G. Petzold: Unusual feeding performance of a dark python (Python molurus bivittatus) . The zoological garden - magazine for the entire zoo, Volume 28, Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Leipzig 1963/1964, pp. 200–202.

- ^ JB Andersen, BC Rourke, VJ Caiozzo, AF Bennett, JW Hicks: Physiology: postprandial cardiac hypertrophy in pythons . In: Nature , Volume 434, 2005, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ JM Starck, K. Beese: Structural flexibility of the intestine of Burmese python in response to feeding . In: Journal of Experimental Biology , Volume 204, Issue 2, 2001, pp. 325-335.

- ^ J. Overgaard: The Effects of Fasting Duration on the Metabolic Response to Feeding in Python molurus: An Evaluation of the Energetic Costs Associated with Gastrointestinal Growth and Upregulation . In: Physiological and Biochemical Zoology , Volume 75, Issue 4, 2002, pp. 360-368.

- ^ T. Walsh, JB Murphy: Observations on the husbandry, breeding and behavior of the Indian python. In: International Zoo Yearbook , Volume 38, 2003, pp. 145-152.

- ↑ DG Barker, JB Murphy, KW Smith: Social behavior in a captive group of Indian pythons, Python molurus (Serpentes, Boidae) with formation of a linear social hierarchy . In: Copeia , Vol. 3, 1979, pp. 466-471.

- ^ A. Vinegar: Evolutionary implications of temperature induced anomalies of development in snake embryos . In: Herpetologica , Volume 30, Issue 1, 1974, pp. 72-74.

- ^ F. Wall: Snakes collected in Burma in 1925 . In: Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society , 1926, pp. 558-566.

- ↑ a b c d e f g H. Bellosa: Python Molurus - the tiger python . Terrarium library Natur und Tier-Verlag 2007, pp. 4–40, 81–91, 106–107. ISBN 978-3-937285-49-8 .

- ^ TVM Groot, E. Bruins, JAJ Breeuwer: Molecular genetic evidence for parthenogenesis in the Burmese python, Python molurus bivittatus . In: Heredity , Volume 90, 2003, pp. 130-135.

- ↑ FL K Lim, MT-M. Lee: Fascinating Snakes of Southeast Asia - An Introduction . Tropical Press, Kuala Lumpur 1989. Quoted in: R. de Lang, G. Vogel: The snakes of Sulawesi: A field guide to the land snakes of Sulawesi with identification keys . In: Frankfurt Contributions to Natural History , Volume 25, Frankfurt am Main, Edition Chimaira 2005, p. 200. ISBN 3-930612-85-2 .

- ^ WCS Lao program: Biodiversity Profile for Luang Namtha Province . In: Biodiversity Country Report 2003, p. 57; online, pdf .

- ↑ BL Stuart: The Harvest and Trade of Reptiles at U Minh Thuong National Park, southern Viet Nam . Traffic Bulletin Volume 20, Issue 1, 2004, pp. 25-34; (online: PDF ).

- ^ NQ Truong, R. Bain: An assessment of the herpetofauna of the green corridor forest landscape, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. Technical Report, Volume 2, 2006, pp. 24, 25, 28 (full text, pdf).

- ^ CITES - Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora: Appendices I, II and II, valid from 1 July 2008; online .

- ↑ D. Chiszar, HM Smith, A. Petkus, J. Dougherty: A fatal attack on a teenage boy by a captive Burmese Python (Python molurus bivittatus) in Colorado . In: Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society , Volume 28, 1993, pp. 261-262; Contents partly reproduced in [1] .

- ^ JB Murphy: Wild and ferocious reptiles in the Tower of London. In: Herpetological Review , Volume 37, Issue 1, 2006, pp. 10-13 (online: PDF ).

- ↑ Swiss Animal Welfare Ordinance of April 23, 2008; online, pdf .

- ↑ Austria: Animal Protection Act, Federal Law Gazette I No. 118/2004 as amended (Section 25) online .

- ↑ Austria: Animal Husbandry Ordinance, Federal Law Gazette II No. 486/2004 as amended : Minimum requirements for keeping reptiles (see 2.2.54); online, pdf .

-

↑ Austria: state-specific regulations for tiger python keeping:

- Vorarlberg: Law on measures against noise disturbances and on keeping animals LGBl. No. 1/1987, 57/1994 (§ 2 Paragraphs 2 and 3), authorization requirement ;

- Lower Austria: Section 7a of the Lower Austrian Animal Welfare Act LGBl. 4610-3 , random checks, ordinance on wild animal species whose keeping is restricted - State Law Gazette 4610 / 3-0 (Section 1), at the Boiden spp. only Python reticulatus, Python sebae and Eunectes murinus prohibited for private use;

- Carinthia: Ordinance with which those animals are determined which are to be classified as dangerous because of the danger they pose for the physical safety of people LGBl No. 21/1991 , prohibition of over 3 meters long giant snakes for private individuals ;

- Upper Austria: § 6 of the O.Ö. Police Criminal Law - Keeping dangerous animals online, pdf , keeping allowed, district administrative authority inspects annually;

- Salzburg: Keeping allowed, random checks, registration form, State Security Act § 2d online, pdf , municipalities are authorized to issue a local ban on keeping animals;

- Vienna: 1st Vienna Animal Welfare and Animal Keeping Ordinance LGBl. 22/1997 (§ 3), keeping of Python bivitattus prohibited for private individuals , all reptile keeping are checked.