Right stretch of the Moselle

| Treis-Neef | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Measurement table from 1940, with Treiser tunnel and embankments

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Route number (DB) : | 3113 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Route length: | 6.91 km | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gauge : | 1435 mm ( standard gauge ) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A planned and partially completed, but not in operation, standard-gauge railway line on the lower Moselle between Bullay and Koblenz is referred to as the right Moselle route . The most striking structure on the route was the Treiser Tunnel , at 2565 meters the seventh-longest railway tunnel in Germany at the time. In a broader sense, the term also includes a railway line from Trier to Neuwied that was planned from a military-strategic point of view , as the section of which the line should have acted.

history

Regional development railway in the Cochemer Krampen

After the completion of the Moselle route in 1879 and the Moselle Railway in 1905, most of the wine - growing towns along the lower Moselle between Trier and Koblenz were connected to the railway either directly or indirectly via a ferry connection. The only exception was the area of the Cochemer Krampen , as the Moselle route through the Kaiser Wilhelm Tunnel shortened the three Moselle loops that form the Krampen. As early as 1893, a railway was also discussed at irregular intervals in this area of the Moselle. But it became concrete for the first time in September 1905, when the mayor of the municipality of Senheim , which at the time was also the seat of a mayor's office , suggested in a memorandum to the President of the Rhine Province in Koblenz that a railway should be built in the affected area and on to Koblenz on the right bank of the Moselle to build. In addition to improving local traffic conditions, it was also pointed out that in the event of a military conflict with France, another route would be available in addition to the Moselle route for mobilization . The paper was also signed by citizens of other affected communities. At the suggestion of the Upper President, the memorandum was sent to the responsible minister in Berlin, as well as a further letter from the group, now operating as a committee to strive for a right-wing Moselle state railway Bullay-Coblenz , to the Prussian mansion with the request to provide the funds necessary for the construction of the line.

In their initial statements, both the Oberpräsident and the Oberbergamt in Bonn supported the project, the latter with reference to a total of 34 ore deposits along the route that could be mined after the railway was completed. The Chamber of Commerce in Koblenz also wrote to the minister and doubted that the local traffic volume would justify such a connection, but still supported the construction, as they could understand the military aspects mentioned. Based on these submissions, the mansion recommended that the government pursue the plan to build the route.

At the same time, the question arose who should carry out the construction and operation. Since the railway to be built in Bullay would have had a connection to the newly built Moselle Railway, it would have been obvious that either it or the West German Railway Company , which built the Mosel Railway and was also in charge of operations there, would have taken over. Both companies declined, however, as the construction of the Moselle Railway had already devoured 16 million marks and another project of a similar magnitude would have exceeded the financial possibilities. Since the circles involved were also out of the question, from his point of view the only thing left for the Koblenz regional president was to build a state railway . It should be noted, however, that the new railway could relieve the existing, heavily traveled Moselle route, but that this would be unnecessary if the proposed canalization of the Moselle were implemented. Now the responsible railway directorate in Saarbrücken has spoken. She was of the opinion that the local transport requirements would by no means justify the construction of a railway, nor would the Moselle route have reached the limit of its capacity. In addition, reference was again made to the potential Moselle canalization.

The ministry in Berlin now adopted this negative attitude and instead suggested in June 1906 the construction of a subgrade on the left bank of the Krampens. The committee, on the other hand, did not believe in such an overland tram . But since the district president saw no need for further discussion, the whole thing fell asleep.

Strategic railroad

The route became a topic again after the government in Berlin in 1912 had made the decision not to pursue the already half-hearted plans to channel the Moselle and instead to expand the railway line along the Moselle. The committee immediately spoke up again, and in its name the district administrator of the Zell district presented another memorandum in early 1913 , which was largely the same as that of 1905. Since he was aware of the change of opinion in Berlin, the Oberpräsident in Koblenz supported the request. A petition from a winery owner from Poltersdorf to build a line between Koblenz - Cond - Alf - Trier was signed by several hundred people from different places. In the meantime, the district administrator of the Wittlich district had also spoken out and, instead of expanding the existing one, called for an additional, parallel route for his area in order to directly connect some places in the Wittlich depression that were not adequately developed by the Moselle route . Officials, communities, associations and other groups and people came forward from other locations along the route and also from remote areas and expressed requests, suggestions or concerns.

Finally, in May 1914, the railway directorate in Saarbrücken was commissioned to initiate detailed planning. The planned strategic route was to be built from Ehrang either to Ürziger train station or to Bullay as a third and fourth track along the existing route through the Wittlich depression , but at the latest from Bullay on a separate route on the right bank of the Moselle to the Koblenz freight station Lützel . Beyond Koblenz, the line was to be continued in a new bridge to be built over the Rhine in order to establish a connection to the railway line on the right bank of the Rhine at Neuwied .

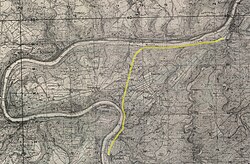

During a tour of the lower Moselle on June 30, 1914, representatives of the railroad management presented the rough plan in the presence of several affected district administrators and other political decision-makers. As was usual with the routes built under military-strategic aspects at that time, engineering structures were very generous. The new double-track line to be built should leave the existing one in the area west of Alf, initially remain on the left bank of the Moselle, and only change to the right bank of the Moselle by means of a bridge at Neef in order to cross the old line there. The station in Bullay should be connected with a separate bridge north of the village. From Bruttig , the route should be led through a longer tunnel under a foothill of the Hunsrück , bypassing Valwig , Cochem and Cond, directly to Treis . At Moselweiß , the route should be merged with the existing Moselle route. Part of the planning was also a short, independent route at Quint in order to bypass the Meulenwald tunnel by means of a viaduct .

Immediately, the mayors of Senheim, Beilstein and Treis spoke out negatively, as their places were to be cut off from the Moselle by a dam. This was just as unsuccessful as the complaints of the city of Cochem and the municipality of Cond that they would not be affected by the new route. The latter were rejected on the grounds that such a tour would lengthen the route by nine and a quarter kilometers and cause additional costs of 8.5 million marks. On the part of the supporters, the debate should primarily revolve around the question of the location of train stations and bus stops.

Bruttig – Treis with Treiser Tunnel

With the beginning of the First World War in August 1914, planning was suspended for the time being. It was not until June of the following year that the ministry in Berlin asked the railway authorities to submit their plans as soon as possible so as not to delay the start of construction work any further. This took place in the same year. In the period that followed, dams, retaining walls and creek passages were built in and near Bruttig, Fankel , Alken , Beilstein and Treis (see also: Bruttig-Fankel # The railway embankment in Bruttig ). The Treiser Tunnel was drilled at the beginning of 1918, and the excavated material was mainly used to build a dam across the town of Bruttig. In the meantime, progress had also been made elsewhere. The Rhine bridge between Urmitz and Neuwied was built between 1916 and 1918 and then put into operation as the Crown Prince Wilhelm Bridge , the forerunner of today's Urmitz railway bridge . Construction of the Quinter Viaduct began in 1917. At the end of the war at the end of 1918, all work was temporarily suspended.

In 1919, with the tolerance of the French occupation authorities, at least the construction of the section that had begun could be continued. The breakthrough took place on December 20, 1919 . A 195 meter high shaft for ventilation of the tunnel was also completed. The dam, which was split in half by Bruttig, was also continued. Each of the twelve streets and alleys that intersected it was given an underpass. One of these had the largest round arch that had been created in railway construction up to that point. After the tunnel work was completed in 1923, it was walled up. At that time it would have been the seventh-longest railway tunnel in Germany with a length of 2565 meters. Only Kaiser Wilhelm , Schlüchtern , Fahrnauer , Krähberg , Brandleite and Rudersdorfer tunnels surpassed it .

Overall, however, it was initially assumed on the Moselle that the construction of the route would also continue beyond the section that was started. For example, a petition to the German National Assembly, with reference to Article 150 of the Constitution , requested that the route in Beilstein not be built between the village and the Moselle, but on the mountain side of the village for reasons of landscape protection . The route "was one of the most expensive that has ever been made in the Rhineland".

Again unsuccessful struggle

Behind the scenes, however, there was heated discussion about the future of the route. The Versailles Treaty of June 1919 indirectly provided in paragraph 43 the prohibition of the construction of strategic railway lines in a zone along the Rhine and in all areas to the west of it. In a note from the Allies in May 1922, further construction of the entire route was accordingly prohibited. In Berlin too, people were aware that a strategic railway would be nonsensical due to the changed conditions. If the line has a future, then only to meet local needs and as a diversion in the event of a disruption in the Kaiser Wilhelm Tunnel. Accordingly, the double connection to the Moselle route by means of two bridges in the Bullay area was discarded in favor of a direct, bridge-free connection to the Petersberg tunnel near Neef, north of Bullay. The same applied to all plans to continue in the direction of Trier, although the Quinter Viaduct was completed in 1922 without ever going into operation in the following period. Down the Moselle between Treis and Koblenz there should not be any further construction, instead the railway should be connected to the existing route by means of a bridge at Karden. Logically, the route now traded under the title Neef-Carden .

A decree by the Minister of Commerce and Industry of August 7, 1923 clarified the new situation, but at the same time made it clear that, if at all, construction would only be continued if those interested in building the line held back with further demands and, in addition, granted subsidies would be willing to afford. The municipalities offered to provide common land free of charge, but the ministry expected all land to be provided free of charge and all ancillary services to be provided.

This negotiation phase was put to an end by both hyperinflation and a decree by the French occupation authorities to stop all work. Finally, the construction company, Grün & Bilfinger from Mannheim , moved out, and in 1924 the construction site was quiet. Up to this point in time, construction costs of nine million marks had arisen.

In autumn 1924 the Senheim Railway Committee spoke up again. With a letter to the German delegation entrusted with negotiations with the Rhineland Commission , they hoped for approval to resume construction work and emphasized that the line had actually only been a local branch line from the start. At the same time, nine municipalities along the route and the participating districts of Cochem and Zell joined together to form a special purpose association , initially to note that the minister's demands on the municipalities would be financially impossible to meet. A delegation from this special purpose association traveled to Berlin in April 1925. There was definitely a general benevolence as well as the fundamental readiness of the Reichsbahn; However, it lacked the financial means, since income and assets were pledged as reparations . The state of Prussia also refused to make payments to the Reichsbahn and was at best prepared to grant the municipalities a subsidy for the costs of real estate acquisition.

In the following period, the project was taken up in Berlin at irregular intervals. According to statements made by the Reich Ministry of Transport in 1926, another 10.5 million marks would have to be raised to complete a stretch from Karden to Neef.

At the beginning of 1927 the project was missing in lists of railway lines to be built as part of job creation measures, but at the end of the year it reappeared in an application by the Reichstag for a Reichsbahn construction program for 1927, but now as a shortened variant in the form of a branch line to Treis. The Moselle crossing in the direction of Karden was only given in brackets; the construction costs calculated at 7.05 million marks over a route length of 23 kilometers. However, the Reich government emphasizes that neither the state nor the Reichsbahn are able to cover the costs of such a construction program. The Reichsbahndirektion Trier , which was commissioned by the Reichsbahnhauptverwaltung to carry out preliminary technical planning and an economic calculation, presented its results in January 1928. So far 9.5 million marks have been built, a further 7.6 million would be needed. If a Moselle bridge between Treis and Karden were not used and the construction was very simple, this amount could be reduced to almost 6 million marks. In addition, there would be another 855,000 marks for the purchase of land. A double crossing of the Moselle at Fankel and Briedern to protect the townscape of Beilstein would result in additional costs of 900,000 marks. In addition, an annual operating cost deficit of 48,000 marks is to be expected.

The final end of the railway plans in the Cochemer Krampen took place in the summer of 1933. In a letter to the district president in Koblenz on August 7th, the Reichsbahn's head office regretted that construction was being carried out due to the missing six million marks and the expected total profitability of the railway also out of the question in the context of job creation measures.

Mushroom cultivation

One possibility for further use of at least the tunnel system, as with other non-operational ( Liblar – Rech route ) or disused tunnels such as the old Rosenstein tunnel, was the cultivation of edible mushrooms. From 1937 onwards, the Saar-Mosel mushroom cultivation of the Spanish merchant Wilhelm Alcover was growing mushrooms. This first larger company in Bruttig offered a number of people from the village a job.

Underground armaments factory, concentration camp, destruction

The inglorious final chapter in the history of the line began in the spring of 1944. As part of an emergency program to relocate essential armaments to protected underground facilities , an underground factory for spark plugs and other electronic accessories for the aircraft industry was to be built for Robert Bosch GmbH (under the code name WIDU GmbH) become. The overall project was given the code names Zeisig and A7 .

For the preparation of the production facilities as well as, in addition to regular workers, for later work in production, the use of prisoners from concentration camps was planned. At the beginning of March 1944, a first command with 300 mainly French so-called NN prisoners from the Alsatian Natzweiler concentration camp arrived in Bruttig, half of whom were transferred to Treis the following day. Initially only temporarily housed in private buildings, heavily guarded barracks were built for them on the railway line on both sides of the tunnel during the spring. Thus, under the official name of the Cochem subcamp , the Bruttig-Treis concentration camp was created as the subcamp of Natzweiler.

Under inhumane circumstances, the prisoners first had to free the tunnel from the remains of the mushroom cultivation and then expand it and add underground chambers as well as adjoining above-ground structures. At the beginning of April the French prisoners were transferred back to Natzweiler and replaced by 700 Polish and Russian prisoners from the Majdanek concentration camp . On July 24th, the total occupancy of the camp consisted of 1,527 inmates, a total of over 2,000 inmates were interned there during its existence.

Production could begin in June 1944, but the systems were partially dismantled again in late summer and relocated to the Stuttgart and Bamberg areas. On September 14, 1944, the remaining 600 prisoners were deported to the Harz Mountains, first to the concentration camp in Nordhausen and later from there to the Ellrich camp . Up until January 1945, around a dozen civil Bosch employees operated a press in the tunnel.

There is no evidence for rumored statements that parts of the V2 rockets were produced in the tunnel or that so-called Nazi gold was walled into niches .

After Allied troops took over the region, the interior of the tunnel and the portals were destroyed by several explosions at various points in the summer of 1946 by order of the French occupation authorities.

Current condition

The most striking remnant of the route is the up to ten meter high embankment, faced with stones and built from excavated material from the tunnel construction, which divides the town of Bruttig. In the northern part of the village it looks like a city wall . The twelve inner city underpasses are all still there. Since the route over it never went into operation, it can be viewed as twelve interconnected soda bridges . The surface of the dam is used as a garden or for viticulture; traces of it are lost in the transition area towards the Fankel district.

By blowing up the portals, the Treiser Tunnel is no longer visually recognizable. The leading dams with their brook passages are still there. On the Treis side there is an asphalt path today, while viticulture is practiced on the Bruttiger side. The remains of two concrete structures can still be seen there below the mouth of the tunnel, which served as water extraction systems, emergency access and protection against bombing, and which were built in the 1940s. On the gross side, there is still a side entrance, which is closed by Deutsche Bahn, to an area around eighty meters long, immediately behind a concrete gate built in 1944 to close the production plant. According to Jörg Neidhöfer, the chairman of the Friends of Kanonenbahnweg and Prinzenkopf association in Zell , an inspection carried out on Good Friday 2007 revealed that the tunnel was completely buried from then on. The current condition of the interior of the tunnel and the possible presence of remains of the production facilities are unknown. The upper opening of the air shaft was closed with a concrete cover in the mid-1980s and the turret-like structure was removed. Structural remains are no longer recognizable.

A relic of the tunnel construction can be found on the section of the Moselle route west of Pomerania at the foot of the Galgenberg opposite the tunnel mouth on the Treiser side . A loading platform for the delivery of construction material was built there, which was then transported to the construction site via a temporary bridge. After the work was completed, the loading track was converted into a main track , as it was made of newer rail material than the original. Even today, the tracks in this area are unusually wide apart.

As far as the further planning of the route is concerned, the extension from Koblenz to Neuwied is the only part that ever went into operation and is still in use today. The original Kronprinz-Wilhelm-Brücke was destroyed by German troops in 1945 and replaced by the Urmitzer railway bridge in 1954. The Quinter Viaduct, completed in 1922, never went into operation and was dismantled in 1979. Parts of the demolition material were used to build a house in Trier.

After Deutsche Bahn, as the owner of the area, began to renovate the railway embankment in Bruttig and this took much longer than originally planned, it was announced in early 2013 that it was considering selling the 6000 m² area within the town. This was welcomed by the community, as it was of the opinion that this area could be used sensibly in the context of local development. The State of Rhineland-Palatinate granted a grant for a feasibility study with regard to the maintenance or removal of the dam, and further state funding was promised. After an entrepreneur commissioned by the municipality had estimated the demolition costs that the municipality would have to bear at 500,000 euros, the plans were abandoned in November 2014.

Alternative names

In addition to the term "right Moselle route" as a counterpart to the Moselle route that runs largely on the left bank of the Moselle and is still used , other terms such as right bank Moselle railway or Moselle railway on the right bank are also used in the literature . However, there is a risk of confusion with the former Moselle railway from Bullay to Trier, which also ran on the right bank of the Moselle. As described above, other names were also used depending on the planning status. The section completed except for the tracks is listed in the Deutsche Bahn route directory under the name Treis-Bruttig . The route number is 3113, the starting point is 53.230 kilometers and the end point 60.140, i.e. a length of 6.91 kilometers.

literature

- Kurt Hoppstädter : The railways in the Moselle valley according to the files of the Koblenz State Archives . Printed by the Saarbrücken Federal Railway Directorate, 1973.

- Karl-Josef Gilles: Unrealized railway projects in the district area . In: Yearbook for the Cochem-Zell District 2003, Cochem 2002, p. 21ff. ISSN 0939-6179 .

- Ludger Kenning, Manfred Simon: The Moselle Railway Trier-Bullay . Nordhorn 2005, ISBN 3-927587-36-2 , pp. 45f.

- Gerd Wolff: German small and private railways . Volume 1: Rhineland-Palatinate. Freiburg 1989, ISBN 3-88255-651-X , p. 85

Web links

- Information and photos about the route and the tunnel ( Memento from January 13th, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) at Empfangsgebäude.de

- Current photos of the railway embankment on the Treiser page on the website of Jörg Neidhöfer

- The underground production facility in the Treiser Tunnel 1944 ( memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) at WikiUunterirdisch

- The concentration camp on the embankment and the armaments factory in the tunnel on Ernst Heimes' website

- Information on the planned route Treis-Karden - Bruttig. With tunnel photos from 2002 on Lothar Brill's website

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c route directory of the Deutsche Bahn. XLS; 118 KiB or PDF; 213 KiB Both accessed on February 10, 2012.

- ↑ Information and pictures about the tunnels on route 3113 on eisenbahn-tunnelportale.de by Lothar Brill

- ↑ a b Information board in Bruttig

- ↑ Article 150 at Wikisource

- ^ Reichstag protocols 1919/20, No. 2872 of April 27, 1920

- ^ HJ: For 100 million murdered railway lines . In: Mainzer Anzeiger from August 16, 1933.

- ↑ Paragraph 43 of the Versailles Treaty at documentarchiv.de

- ↑ Reichstag Protocols, 1924/28, No. 2116, p.4, of March 28, 1926.

- ^ Memorandum of the Reich Minister of Labor on the Reich Government's job creation measures . Protocols to the Reichstag 1924/27, No. 2921 of January 24, 1927

- ^ Statement of the Reich Government on this

- ↑ Compilation of the railway constructions applied for for a Reichsbahn construction program. . Reichstag protocols 1924/28, No. 3847, Annex 1, p. 116, of December 7, 1927.

- ^ Statement by the Reich Government , Reichstag Protocols, 1924 / 28.37, No. 3847, p. 6, of December 7, 1927.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pechtold: Delicate white "blossoms" from deep darkness . Article on the Ahrweiler District website , accessed on February 16, 2019

- ↑ Information about the Silberberg tunnel on the website of the Alt-Ahrweiler Heimatverein, accessed on February 16, 2019

- ↑ Old Rosenstein tunnel: light at the beginning of the tunnel . In: Stuttgarter Zeitung , September 15, 2010, accessed on September 25, 2010.

- ↑ On the story of Bruttig-Fankel on the website of the Bruttiger Weingut Ostermann

- ↑ Bruttig-Fankel (with aerial photo) at die-mosel.de, accessed on February 16, 2019.

- ↑ Press release on the 2017 Annual General Meeting on the website of the City of Zell, June 28, 2017, accessed via Focus Online on February 16, 2019.

- ↑ Tunnel Bruttig-Fankel / Treis ( Memento from July 14, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) in the Railway Forum of the Middle Rhine Region, December 11, 2009. Memento from July 14, 2012 in the web archive archive.today .

- ↑ https://eisenbahn-tunnelportale.de/lb/inhalt/tunnelportale/3113-treis-innen.html Pictures from June 2002 from the inside of the tunnel

- ↑ Answer from Jörg Neidhöfer to a corresponding request in the Railway Forum of the Middle Rhine Region, September 6, 2009, accessed on February 16, 2019.

- ^ The demolition of the Kronprinz-Wilhelm-Brücke . In: Bendorfer Zeitung , March 9, 1955, on the tenth anniversary of the demolition. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ↑ Entry on the former railway viaduct (Ehrang-Quint) in the database of cultural assets in the Trier region ; accessed on February 24, 2016.

- ↑ Dieter Junker: Is the gross embankment about to be demolished? ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Rhein-Zeitung, January 29, 2013.

- ↑ Dieter Junker: The embankment will probably remain. Rhein-Zeitung, November 14, 2014, accessed on February 16, 2019.