Fredonian Rebellion

The Fredonian Rebellion or the short-term, resulting Republic of Fredonia (December 21, 1826 to January 23, 1827) was the first attempt by Anglo-American settlers in Texas to separate from Mexico . The settlers, led by the Land Empresario Haden Edwards, declared their independence from Texas, Mexico and founded the Republic of Fredonia near Nacogdoches .

overview

The Republic of Fredonia was the result of a brief rebellion , which was suppressed or collapsed after a month. The place of the outbreak was territory that the Mexican government had granted to the American Haden Edwards in 1825 , but had already been settled by immigrants of Spanish origin in the decades before . Edward's actions quickly alienated the established residents, and the increasing hostility between them and settlers recruited by Edwards led Victor Blanco, as the local governor of the Mexican government, to revoke the settlement agreement signed with Edwards.

In return, a group of Edwards' supporters took control of the region in late December 1826. They removed several community officials associated with the established residents from office, flanked them with some arrests , and declared their independence from Mexico. Although a nearby Cherokee tribe led by Chief Richard Fields initially signed a treaty in support of the newly proclaimed republic , the Mexican authorities and the respected Empresario Stephen F. Austin convinced the tribal leaders to reject the rebellion. On January 31, 1827, a force of over 100 Mexican soldiers and 275 militiamen from Stephen Austin's land charter to the southwest marched into Nacogdoches to restore order. Haden Edwards and his brother Benjamin fled to the United States. Chief Richard Fields was killed by members of his own tribe. A local trader was arrested as a ringleader and sentenced to death, but was released shortly afterwards.

The rebellion prompted Mexican President Guadalupe Victoria to increase the military presence in the region. One of the effects of this military presence was that several hostile tribes in the region stopped their raids on settlements and agreed to sign a peace treaty - a measure that specifically changed the relationship between the Comanche who ruled the southern prairie and the Mexicans for the better. Fearing that the rebellion would bring the United States to control of Texas, the Mexican government severely restricted US immigration to the region. In return, the new immigration law was bitterly rejected by the Anglo-Saxon colonists and led to increasing dissatisfaction with Mexican rule. A number of historians see the Fredonian Rebellion as the very beginning of the Texan Revolution .

background

During the period of Spanish colonial rule , the northeastern part of New Spain - the province of Texas - was in the focus of Anglo-Saxon settlers, land speculators and adventurers. Especially the eastern part of the province with the district capital Nacogdoches developed more and more into the scene of Anglo-Saxon settlement and land grabbing activities at the beginning of the 19th century . Two early ventures were the Gutiérrez-Magee Expedition 1812/1813 and the Long Expedition 1819 to 1821. Both were typical filibuster operations that were planned and carried out by individual actors. The aim of these short-lived incursions into the sparsely populated area was to create facts through military action and the proclamation of an independent Texan Republic. Both actions quickly failed. The expedition of Bernardo Gutiérrez and Lieutenant Augustus Magee was wiped out by the Spanish-Mexican forces, as was that of Dr. James Long six years later.

After the victory in the Mexican War of Independence in 1821, several colonies of the former viceroyalty of New Spain merged to form a new state - Mexico. The new state was divided into several provinces , and the area known as Mexican Texas became part of the border provinces of Coahuila and Tejas . In order to rule the large area, the province was further subdivided; in the course of this subdivision, Mexican Texas was assigned to the district of Béxar (today: San Antonio). At the local level, the area was divided into smaller administrative units, each ruled by an alcalde - a function roughly equivalent to that of a current mayor . A large part of East Texas - extending in an east-west direction roughly from the Sabine River to the Trinity River , in a south-north direction from the Gulf Coast to the Red River - became part of the municipality of Nacogdoches. Most of the community's residents were Spanish-speaking families who had ruled their land for generations. An increasing number were English-speaking residents who immigrated illegally during the Mexican War of Independence. Many of the immigrants were adventurers who had arrived as part of various military filibuster groups with the intent to create independent republics within Texas during Spanish rule .

In order to better control the sparsely populated border region, the Mexican federal government passed the General Colonization Law in 1824 . The new law was designed to allow legal immigration to Texas. According to the law, each province should set its own requirements for immigration. After a debate on March 24, 1825, the provincial government of Coahuila and Tejas approved a system that made land available to the empresarios - provided that they each recruited settlers for their own colony . In addition, for every 100 families that settled in Texas, they were given around 93 square kilometers of land to grow and settle.

During the deliberations on the law, a number of potential charter candidates traveled to Mexico in order to obtain an assignment. Among them was Haden Edwards, an American land speculator known for both speed and aggressive methods. Although Edwards behaved rather undiplomatically in Mexico and offended a number of members of the Mexican administration, he received a land acquisition treaty on April 14th , which allowed him to settle 800 families in East Texas. Part of the contract was, among other things, a standard clause which obliged Edwards to recognize all existing Spanish and Mexican land titles in his grant area, to set up a militia to protect the settlers in the region and to allow the state land commissioner to certify all certificates issued .

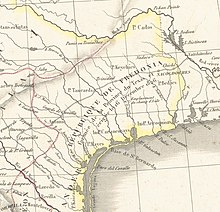

In a west-east direction, Edward's colony comprised the land from the Navasota River to 32 kilometers west of the Sabine River, from south to north an area beginning 32 kilometers north of the Gulf of Mexico to 25 kilometers north of the city of Nacogdoches. To the west and north of the colony were lands controlled by several Indian tribes recently expelled from the United States. The southern border was formed by the colony of Stephen F. Austin, the son of the first Anglo-American charter holder on Texan soil. To the east of Edward's colony was the former Sabine Free State , a neutral zone that had been established in 1806 as a buffer between the state territories of the USA and New Spain-Mexico and had subsequently developed into an El Dorado for outlaws , land grabbers and smugglers . The boundaries of the new colony and the municipality of Nacogdoches partially overlapped, which subsequently led, among other things, to uncertainty about which authority was responsible for which function.

Prehistory of the rebellion

Edwards arrived in Nacogdoches in August 1825. Assuming he had authority to determine the validity of existing land claims , Edwards requested written proof of ownership from the old settlers in September . Otherwise, Edwards said, their claims would be forfeited and the land would be sold at auction . According to current historians, his harsh demeanor in the colony was at least partly driven by prejudice: Edwards despised those who were poorer or of a different race . Beyond that, however, his declaration also had an immediate, tangible intention: by expropriating less affluent settlers, he could assign his land to wealthy planters who - like himself - came from the southern states of the United States .

Very few of the English-speaking residents had valid titles. Those who did not arrive as land developers were deceived by fraudulent land speculators . Most Spanish-speaking landowners lived on land owned by their families for 70 or more years; As a rule, there were no papers to prove this. Anticipating the conflict between the new empresario and the area's long-time residents, the parish's incumbent alcalde, Luis Procela, and parish clerk Jose Antonio Sepulveda began validating old Spanish and Mexican land titles. In response, Edwards accused the regional administration of creating a fait accompli - an accusation that further angered residents.

By December 1825, Edwards had recruited 50 families willing to emigrate from the United States and join his colony. As stated in his contract, Edwards organized a local militia open to both his new colonists and local residents. When the militiamen voted community servant Sepulveda captain , Edwards canceled the results and declared himself chief of the militia. After this debacle, Edwards demanded - again overriding his powers - elections for a new alcalde. Two candidates ran for the appointed office: a) Edward's son-in-law Chichester Chaplin, who was seen as a representative of the newly arrived immigrants, b) Samuel Norris - an American who had married the daughter of a long-time resident and was therefore favored by the long-established residents . After Chaplin's victory, members of the defeated party turned in an appeal to Juan Antonio Saucedo, the prefect of the department of Béxar. In March Saucedo overturned the election results and declared Norris the winner - which in turn resulted in Edwards refusing to recognize Norris authority.

Shortly after Saucedo's decision, Edwards left the colony to recruit more settlers from the United States. His younger brother Benjamin took responsibility for the colony. However, this could not maintain the stability within the colony. The situation quickly deteriorated. A vigilante group of long -established settlers treated many newcomers with reprisals . Benjamin Edwards then filed several complaints with state authorities. Annoyed by the nature of the incident and the mounting tensions within the colony, Mexican authorities revoked Edward's land charter in October and ordered the two brothers to leave Mexico. The decision may have been influenced by rumors that Haden Edwards had only traveled to the United States to raise an army . Unwilling to write off his investment of around US $ 50,000 (roughly the current value of US $ 1,100,000), Haden Edwards returned to Nacogdoches in late October 1825 and continued to operate the colony - despite the fact that the associated contract had been terminated had been.

Course of the rebellion

In October, Norris, as reigning Alcalde, ruled that Edwards had illegally taken land from an existing settler to reallocate it to a new immigrant. Norris revoked the property rights of the new immigrant and angered many of the colonists. Later that month, another new immigrant was arrested and ordered to leave the country after refusing to obtain a trading license to trade with the surrounding Indian tribes . On November 22, 1826, the local militia colonel Martin Parmer and 39 other Edwards colonists occupied Nacogdoches and arrested Norris, Sepulveda and the commander of the small Mexican garrison. The accusation: Norris and Sepulveda had encouraged oppression and corruption within the colony. Haden Edwards was also arrested for violating his deportation order, but was paroled - possibly, according to today's historians, a ploy to cover up his own involvement in the conspiracy. A court found the other men guilty, removed them from their posts, and forbade them to ever hold public office. The court dissolved after he appointed a provisional alcalde. With Norris' impeachment , the warrant for his arrest was declared invalid.

Throughout the fall, Benjamin Edwards had tried to mobilize the Edwards colonists in a possible armed revolt against Mexican authority. Largely unsuccessful with this matter, he turned to a nearby Cherokee tribe. A few years earlier, the tribe had applied for official title to the Mexican authorities, but never received it. Benjamin Edwards made the following offer to the tribe: a land title for all of Texas north of Nacogdoches in exchange for armed support for its independence efforts.

On December 16, the Edwards brothers invaded Nacogdoches with only 30 settlers and captured the most important military facility within the city, the Old Stone Fort. On December 21, the former Edwards colony declared itself independent and gave itself the name Republic of Fredonia . Within hours of the announcement, the rebels signed a peace treaty with the Cherokee, represented by Chief Richard Fields and John Dunn Hunter. Fields and Hunter claimed to represent 23 other tribes and promised to provide 400 warriors. To emphasize the new situation, the insurgents hoisted a new flag over the Old Stone Fort - the flag of the Republic of Fredonia with two stripes (one red and one white - for the two races) . The motto “ Independence , Freedom and Justice ” was also part of the flag . In order to further promote the secession from Mexico, Haden Edwards sent messengers to Louisiana with orders to solicit military aid from the United States. However, the US Army categorically refused to intervene in Mexican Texas. In addition, the Edwards brothers and their supporters urged Stephen F. Austin and his colonists to join the rebellion. In the neighboring colony to the southwest, the Fredonia supporters also received a rejection. Austin, who took a balancing, diplomatic line with the Mexican authorities , made it clear in a letter to Edwards: "You are deceiving yourself and this deception will ruin you."

The Declaration of Independence was also controversial within the Edwards Colony itself . Many of his colonists were bothered by Edward's lack of loyalty to their adopted country. Others were concerned about its alliance with the Cherokee. The Mexican authorities were also concerned about this. They sent the Mexican Indian Peter Ellis Bean and the administration officer Saucedo to the Cherokee to negotiate with them in turn. They stated that the tribe had not followed the necessary procedures to obtain a land grant, but promised that the Mexican government would fulfill their land claim if they started the application process again. Such arguments, as well as a possible military reaction, convinced many Cherokee not to ratify the treaty with Edwards.

After the news of the arrest of the Alcalde in November, the Mexican government had made preparations for a reprisal . On December 11th, Lieutenant Colonel Mateo Ahumada, the military commander in Texas, marched north from San Antonio de Béxar with 110 infantry members . The troops first stopped in Austin's colony to assess the loyalty of the settlers there. On January 1, Austin announced to its colonists that "Nacogdoches deluded lunatics" had declared independence. Many members of the Austin Colony then volunteered to help put down the rebellion. As the Mexican army advanced towards Nacogdoches on January 22nd, 250 militiamen from Austin's colony joined them.

In the meantime the opponents of the separation within the colony had also made an attempt to change the balance of power on site. Samuel Norris made an advance with 80 men with the aim of retaking the Old Stone Fort. Although the Fredonia Separatist military commander in chief, Colonel Martin Parmer, had fewer than 20 supporters with him, his men beat off Norris' squad in less than ten minutes. On January 31, Ellis Bean marched into Nacogdoches, accompanied by 70 militiamen from Austin's colony. Meanwhile, Parmer and Edwards had learned that the Cherokee had given up any intention of waging war against Mexico. When it became clear that not a single Cherokee warrior would appear to reinforce the revolt, Edwards and his followers fled. Bean chased them all the way to the Sabine River. However, most of the refugees - including the Edwards brothers - managed to escape safely to the United States. Ahumada, his soldiers and the administrative officer Saucedo arrived in Nacogdoches on February 8 and, step by step, restored order.

Although the Cherokee did not take up arms against Mexico, the treaty signed with Chiefs Fields and Hunter caused the Mexican authorities to question the tribe's loyalty. To demonstrate its loyalty to the Mexican authorities, the Cherokee tribal council ordered Fields and Hunter to be executed . The legal basis for this was the tribal law, according to which certain crimes such as supporting a tribal enemy should be punished with death. The death sentence indirectly confirmed that Edwards and his supporters were enemies of the Cherokee. The two chiefs fled but were soon captured and executed. When the executions were reported to the Mexican authorities on February 28, Anastasio Bustamante , commander-general of the interior eastern provinces, praised the Cherokee for their prompt response.

In order to finally pacify the rebellion, Bustamante finally offered a general amnesty for everyone who had participated in the clashes - with the exception of Haden and Benjamin Edwards, Martin Parmer and Adolphus Sterne, a local trader who came from Cologne and for the rebels Had delivered supply. Like the Edwards brothers, the rebel military commander Martin Parmer fled to Louisiana. Adolphus star, however, remained and was due to treason sentenced to death. However, he was released on condition that he swear allegiance to the Republic of Mexico and never again take part in an armed uprising against the Mexican government.

aftermath

The aftermath of the rebellion affected both the relationship of the Anglo-Saxon Texas colonists to the Mexican central authority and to the surrounding Indian tribes. For one, the rebellion changed the dynamics between settlers and local tribes. Although the Cherokee as a whole opposed the rebellion, their initial support caused many settlers to distrust the tribe. The rebellion and the subsequent reaction of the Mexican army also changed the settlers' relations with other tribes. As allies of various Comanche groups, the Tawakoni and Waco had regularly raided settlements in Texas. Fearing that the tribes, like the Cherokee, might ally themselves with other groups against the Mexican supremacy, Bustamante began preparations to attack and weaken potentially hostile Indian tribes in East Texas. When the Towakoni and Waco learned of the impending invasion in April 1827 , they asked for peace. In June the two tribes signed a peace treaty with Mexico and promised to stop all raids on Mexican settlers. As a result, the Towakoni also supported their allies, the Penateka-Comanche, in concluding a corresponding treaty with Mexico. However, when Bustamante's forces left Texas later that year, the Towakoni and Waco resumed raids. The Comanche, on the other hand, upheld their treaty for many years and occasionally even helped the Mexican soldiers recover cattle stolen from other tribes.

The failed rebellion also influenced further relations between the Republic of Mexico and the United States. Even before the revolt, many Mexican officials were concerned that the United States was planning to take control of Texas. When the rebellion broke out, quite a few Mexican officials suspected Edwards was an agent of the United States. To protect the region, a new, larger garrison was set up in Nacogdoches. Colonel José de las Piedras became the commanding officer . As a direct result of Edwards' actions, the Mexican government initiated an extensive investigation, conducted by General Manuel de Mier y Terán, with the aim of validating a course of action in future similar conflicts. Mier y Teran's reports eventually led to the April 6, 1830 law, which severely restricted immigration to Texas. Within Texas, the laws have been widely condemned by both immigrants and native Mexicans. As a result, they led to further armed conflicts between Mexican soldiers and Texan settlers.

Some historians consider the Fredonian Rebellion to be the beginning of the Texan Revolution. In a 1954 article written for the Southwestern Historical Quarterly , author WB Bates classified the uprising as premature. However, he helped spark the passion for later success. The inhabitants of the region around Nacogdoches also played a major role in future rebellions: in the context of the so-called Battle of Nacogdoches in 1832 - another pre-independence war conflict in the northeast Texas region - they drove out the new military governor Piedras and his troops. Many settlers in the region also took part in the Texan War of Independence, which broke out in 1836 and was largely fought on East Texas arenas.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c See overview presentations in A Sketch History of Nacogdoches , WB Bates, The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Volume 59, July 1955 – April, 1956, p. 494 and Fredonian Rebellion . Archie P. McDonald, Texas State Historical Association, June 12, 2010

- ↑ The Nine Flags of Nacogdoches at the Historic Town Center in Historic Nacogdoches , Historic Town Center Nacogdoches, accessed September 27, 2018 (Engl.)

- ^ Joe E. Ericson: The Nacogdoches story: an informal history. Heritage Books, Berwyn Heights (Maryland) 2000. ISBN 978-0-7884-1657-6 , pp. 33 u. 35. (Engl.)

- ^ A b c d e f William C. Davis: Lone Star Rising. Texas A&M University Press / New York Free Press 2004. ISBN 978-1-58544-532-5 , p. 70. (Engl.)

- ↑ a b c d e Fredonian Rebellion . Archie P. McDonald, Texas State Historical Association, June 12, 2010

- ↑ a b c d e Ericson, The Nacogdoches story, p. 37. (Engl.)

- ↑ Ericson, The Nacogdoches story, p. 36. (Engl.)

- ↑ a b Julian Samora, Patricia Vandel Simon, Cordelia Candelaria, Alberto L. Pulido: A History of the Mexican-American People. University of Notre Dame Press, Indiana 1993. ISBN 978-0-585-33332-8 , p. 79.

- ↑ Ericson, The Nacogdoches story, p. 38. (Engl.)

- ↑ Ericson, The Nacogdoches story, pp. 38-39. (Engl.)

- ↑ a b c d A Sketch History of Nacogdoches , WB Bates, The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Volume 59, July 1955 – April, 1956, pp. 491 ff.

- ↑ a b Ericson, The Nacogdoches story, p. 39. (Engl.)

- ↑ Ericson, The Nacogdoches story, p. 40. (Engl.)

- ↑ Dianna Everett: The Texas Cherokees. A People between Two Fires, 1819-1840. University of Oklahoma Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0-585-16884-5 , p. 43. (Engl.)

- ↑ a b c d Everett, The Texas Cherokees, p. 44. (Engl.)

- ↑ Jack Jackson: Indian Agent. Peter Ellis Bean in Mexican Texas. Texas A&M University Press 2005. ISBN 978-1-58544-444-1 , p. 62. (Engl.)

- ↑ a b c Ericson, The Nacogdoches story, p. 41. (Engl.)

- ↑ Jackson, Indian Agent, p. 71. (Engl.)

- ^ A b Everett, The Texas Cherokees, p. 45. (Engl.)

- ↑ Samora et al: A History of the Mexican-American People, p. 80. (Engl.)

- ↑ Jackson, Indian Agent, pp. 65, 67. (Engl.)

- ^ Jace Weaver: That the People Might Live: Native American Literatures and Native American Community. Oxford University Press, New York 1997. ISBN 978-0-19-512037-0 , p. 69. (Engl.)

- ↑ a b c d Davis: Lone Star Rising, p. 72. (Engl.)

- ^ Davis: Lone Star Rising, p. 71; Excerpt from a letter from Stephen F. Austin to Haden Edwards. (Engl.)

- ↑ a b c Everett, The Texas Cherokees, p. 26. (Engl.)

- ↑ Jackson, Indian Agent, p. 75. (Engl.)

- ↑ a b Jackson, Indian Agent, p. 76. (Engl.)

- ↑ Ericson, The Nacogdoches story, p. 42. (Engl.)

- ↑ Jackson, Indian Agent, p. 77. (Engl.)

- ↑ a b Everett, The Texas Cherokees, p. 47. (Engl.)

- ↑ Ericson, The Nacogdoches story, p. 43. (Engl.)

- ↑ Everett, The Texas Cherokees, p. 48. (Engl.)

- ^ F. Todd Smith: The Wichita Indians. Traders of Texas and the Southern Plains, 1540-1845. Texas A&M University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-585-37704-9 . P. 121. (Engl.)

- ^ Smith, The Wichita Indians, p. 122. (Engl.)

- ↑ a b Ohland Morton: Life of General Don Manuel de Mier y Teran. Southwestern Historical Quarterly Issue 47, 1943 / Texas State Historical Association 2009, p. 33. (Engl.)

- ↑ Morton, Life of General Don Manuel de Mier y Teran, p. 34. (Engl.)

- ↑ Davis: Lone Star Rising, pp. 77, 85. (Engl.)