Safarnameh

Safarnāmeh ( Safarnāme, Safarnama, Safarnamah, Safarnoma, Persian سفرنامه, "Book of Travel, Travel Report") is the title of various Persian writings from different epochs. For example, a travelogue by Niẓām Šāmī is known. This article is devoted to the travel diary of the Persian poet and philosopher Nāsir-i Chusrau (Nāser Khosrow).

In his Safarnāmeh , Nāsir-i Chusrau describes the impressions gathered on his travels to Jerusalem , Mecca and Cairo . The accuracy of its descriptions and the accuracy of its descriptions make it one of the most outstanding literary sources for regional studies of the medieval Orient. As one of the oldest New Persian prose works, it is also an important testimony to the study of the development of the New Persian language.

Nāsir-i Chusrau (1003-1088)

The author of Safarnāmeh Nāsir-i Chusrau was a civil servant, world traveler, philosopher, poet and missionary and is still worshiped as a saint by many Ismailis .

Its roots lie in the small town of Qubodijon in what is now southwestern Tajikistan. After many years of activity as a court official and little religious lifestyle, he converted to Ismaili teachings under certain circumstances, about which contradicting information existed, and decided to start the thousands of kilometers long pilgrimage to Mecca .

He wrote his best-known work, Safarnāmeh, about the experiences and experiences of this journey, which in the end would last seven years and which, in addition to Mecca, should also take him to Jerusalem and Cairo . After his return, strengthened by the experiences of the trip and his impressions at the Fatimid court, he devoted himself entirely to missionary work. As a result, however, he soon fell out of favor with the Sunni - Seljuk rulers and was banished to the Yamgan area in the Pamir Mountains . There he ekes out a poor existence under the protection of an insignificant Ismaili prince, although he can continue to write and distribute his writings for a long time until the end of his life at the age of 84.

The travels

The first trip

Before departure

At the beginning of his story, the official and writer Nāser Khosrow describes himself as a not very religious person who liked to talk about wine. On a business trip, however, he is advised in a dream to no longer seek his salvation in drunkenness, but in faith. So he decides to make a pilgrimage to Mecca , gives up his office and moves all his belongings.

Northern Iran and Armenia

On March 5, 1046, he set out from Merw and wandered through relatively familiar areas, which is why his regional descriptions are rather short. He mentions that a solar eclipse was observed about a month after he left . He traveled on via Nishapur , made a few strange little acquaintances, and in July reached Shamiran via Qazwin. There, he writes, “there is such perfect justice and security that nothing can be stolen from anyone. When people go to the mosque on Fridays, they leave their shoes outside and nobody steals them. "

Tabriz describes Nāser Khosrow as a very large city, in which 40,000 people are said to have died in an earthquake four years earlier. From here he reached the shores of Lake Van in mid-November and with it into Christian Armenia . “Here, pork and sheep were sold in the market, and men and women, sitting on benches in front of the shops, drank wine without hesitation.” He travels on against the rigors of winter. He admired the architecture of the cities of Mayyafariqin and Amid, today's Diyarbakır , whose city walls must have left a special impression on him.

The Levant

A little later, around the turn of the year 1046/1047, Nāsir-i Chusrau crossed the Euphrates and reached Syria . He admired the city of Aleppo and its fortress and traveled on to Ma'arrat an-Nu'man . He describes the local mayor Abu 'l-A'la al-Ma'arri as a famous poet who is blind, ascetic and humble, is highly valued by all over the world and has many disciples. Nāsir-i Chusrau is enthusiastic about the description of the city of Tripoli . Its wealth, the bravery of its residents, the beauty of its Friday mosque and many other things arouse his pleasure. He also points out here that the residents are all Shiites . "The Shiites have built beautiful mosques in every country," he says.

On the onward journey he noticed plenty of ruins of marble columns in the vicinity of Beirut , but no one could give him any information about their origin. He praises and describes the cities of Sidon , Tire and Acre as flourishing, as he does with almost all the cities of the Levant. From Acre he made his way into the hinterland at the end of February and wandered further east.

Under the guidance of a Persian whom he met by chance, he made a pilgrimage to the graves of Akks, Esau , Simeons , Huds , Esras , Jethros , the wife and mother of Moses and the brothers of Joseph . He then reached the Dead Sea via Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee and then back to the coast of Acre. Caesarea and Ramla are his last stops before he reached the first important destination of his journey on March 5, 1047: Jerusalem .

Jerusalem, Palestine and the first trip to Mecca

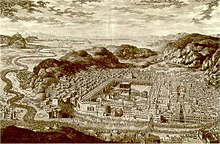

Jerusalem cannot be described here to the same extent and with the same attention to detail as Nāsir-i Chusrau does. From his description, however, the great importance he attaches to the holy city is undoubtedly clear. Even if he does not give up his sober, objective style here either, he is clearly trying to present a complete, in part almost photographic image of what he sees. After the general praise of the city's wealth and beauty, he mainly reports on the Temple Mount with the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock .

The information he gives on this is so precise that Manfred Mayrhofer in his edition of the German translation feels compelled to comment on the relationship between the sides of the Dome of the Rock, which Nāser Khosrow describes as being of equal length: “The eight pages are not all of the same length. The lengths vary between 20.2 and 20.7 meters. ”The report also mentions the tomb of Absalom and the Mount of Olives .

Before he left Jerusalem on his first trip to Mecca on May 13, Naser Khosrow visited the Machpelah cave in al-Khalil with the tombs of Abraham and Isaac and Joseph's tomb in Nablus . He tells us next to nothing about the trip and Mecca itself, but only promises to go into more detail on the city on his last trip, presumably because the time of his first trip did not fall in the month of the Islamic pilgrimage and the trip was therefore only a visiting pilgrimage ( Umra ) was true . Back in Jerusalem, interestingly enough, he dedicates a chapter to the Christian Church of the Holy Sepulcher with a very detailed description of its architecture and its use.

The second trip

From Jerusalem to Egypt

Nāsir-i Chusrau used the time up to the actual month of pilgrimage to undertake a trip to Egypt . To do this, he first traveled from Jerusalem to the coast, to the port city of Askalon . From there it went on to Tinnis by sea. Today contradicting information can be found about the location of this city, but he locates it on an island off the coast of the Nile Delta . At this point, Tinnis is given such a comprehensive and euphoric description that the report stands out from the others. With the help of numerous examples, he describes the special qualities of the textile trade in the city as well as its wealth and excellent organization. So “there is only one tax collector [...]. The tax is never denied and nobody is harshly collecting it ”.

On August 3, 1047, Nāsir-i Chusrau reached Cairo. Before he devotes himself to a more precise description of this city, however, descriptions of Alexandria , the Red Sea , the north African coast and even Sicily and Andalusia are included . Of these, however, he only reports what he has learned from third parties, he has not even been there.

Cairo and the second trip to Mecca

When Nāsir-i Chusrau speaks of Cairo (Al-Qahira al-Mu'izziya), he means the new Fatimid city north of the old city, which he calls "the city of Misr" (Shahr-e Mesr). In any case, the visit and description of this city occupy a central position in Safarnāmeh. First he describes their location in the Nile Valley and the habits of the Egyptians to adapt their way of life to the rise and fall of the Nile level. He tells of the legend that the city was built on the only place where you could cross the Nile without being eaten by the crocodiles.

He describes the splendid court holding of the Shiite-Ismaili Fatimid caliph Al-Mustansir (he calls him “ Sultan ”) as well as the buildings and gardens of his palace. Nāser Khosrow gives a particularly detailed description of the "opening of the Halig", a huge state act with a military parade and folk festival, which has the symbolic opening of the palace canal as an occasion for all other canals in the country. He uses the opportunity to describe the military parade to enumerate the extensive troop contingents that the Fatimid caliph has at his disposal. After these and other depictions of Fatimid splendor, the author comes to the layout of the city itself.

He reports of houses with up to fourteen floors in which 350 people live, of the large market halls as well as of the mosques Ibn Tulun , 'Amr Ibn Al-'As and Al-Atiq that still exist today . He also has a lot of interesting reports on handicrafts and trade, for example that “The Misrs merchants speak the truth, whatever they sell. If someone lies to the buyer, he is put on a camel, gets a bell in his hand and has to ride around the city and shout: I told the untruth. ”A total of 50,000 donkeys are available for rent every day on the market lanes. Nāsir-i Chusrau reports that the Sultan gives a banquet twice a year for the entire population, who then sit and eat in 12 palace buildings at the same time, he too took part in this banquet and uses its description once again to demonstrate Fatimid splendor. The caliph is praised for his generosity and also for the fact that he respects the wealth of others in addition to his own and does not envy anyone. Three quarters of a year later, on April 18, 1048, Nāser Khosrow and a caravan of the caliph set out again for Mecca. He only reveals about the trip that there was great need there and that there was a lack of essentials and that he will report on the city at a later opportunity.

The third trip

After the second visit to Mecca, during which Nāser Khosrow had the opportunity to carry out the full-fledged pilgrimage, he returned to Misr, spent a whole year there in the vicinity of the caliph and traveled to Mecca again the next year with his caravan. He also reports on a group of Persian pilgrims, some of whom died from the exertion of violence imposed on them by their Bedouin leaders. However, he continued to return to Misr without any particular incident.

The fourth trip

From Cairo via Aswan to Mecca

In the following year, 1050, Nāsir-i Chusrau set out from Cairo for the last time in the direction of Mecca. This time in May, right after the festival of sacrifice . The path he chose this time was different. Since he was not traveling with the caliph's caravan, he first took the ship up the Nile to Aswan . On the way he describes Asyut, of which he particularly emphasizes that poppy seeds are grown and opium is produced there and mentions having seen the ruins of Old Thebes near Luxor . He stayed in Aswan for three weeks to gather strength for the hard journey through the desert to the Red Sea.

After 15 days of camel riding through an almost completely waterless wasteland, he reached the coastal town of Aidab on July 28, 1050. He describes them as inhabited by godless pagans, but "they are not bad people, they do not steal or rob [...] The Muslims and others steal their children from them, bring them to the cities of Islam and sell them." Wind was unfavorable, Nāsir-i Chusrau stayed in Aidab for a full three months and preached Islam to the residents. There he enjoyed the hospitality of a man he only knew through a recently made friend and praised his unclouded trust in a person he has barely met. At the end of the three months he embarked for Gidda and reached the gates of Mecca a little later, on November 18th.

Mecca

The description of Mecca is very factual. On this last visit he stayed in the city for six months and worked as a mosque servant, which is of course a particularly godly work in these holy cities. He uses this last visit to describe the processes of the pilgrimage and the place Mecca itself. It is interesting that he describes the processes of the Hajj and the ʿUmra in great detail. This suggests that they were not fully known to the Persian Muslim of his time. He also devotes a large section to the mosque and the Kaaba itself. Obviously at this time it was also possible for the pilgrims to visit the interior of the Kaaba, because he not only includes it in his description, but even describes it as richly adorned and reports that parts of Noah's Ark can be seen in it and how after the opening of the Kaaba by the mosque servants, the pilgrims inside the Kaaba prayed.

About the city itself, he only mentions that it is located in a basin, the center of which is the mosque and has around 2500 inhabitants. Again he reports of great hardship and severe food shortages. It is true that "the caliphs of Baghdad had many beautiful buildings [...] erected, but at the time [...] some had fallen into disrepair, others had become private property."

From Mecca to Basra

On May 4, 1051, Nāsir-i Chusrau left the city of the Prophet and turned to travel home. He chose the route across the Arabian Desert , along the Gulf coast and across Iran . After a final rest in Ta'if , he set off for the desert. He describes this trip as dangerous and unsafe, especially because of the predatory Bedouins. "It is said that here no governor and no ruler commands [...] robbers and murderers fight and feud with one another all day." He also knows about seventy-year-old old people who said "that they have been in their entire lives Have not drunk anything but camel's milk, because in these desert areas there is only salty food that the camels eat and these people believe that it is like that all over the world. ”In the oasis town of Falag near today's Riyadh , he has to take a break and live under the poorest conditions. "The people here were naked, starving, ignorant people," he notes shortly.

After four months he finally had the opportunity to travel on with a caravan to Lahsa in the foothills of the Gulf Coast. Nāser Khosrow reports a lot of interesting things about this city. Its inhabitants are followers of the sect of Abu-Sa'id ( Karmatians ). They recognize the authority of the Prophet, but they do not pray, and they do not even have a mosque. Nevertheless, their form of society is very fair, even benevolent and humane. Regarding their table manners, the author writes with astonishment: “In the city of Lahsa, the meat of all animals such as cats, dogs, donkeys, cattle and sheep is sold. [...] The dogs there are fattened like fat sheep, so that they eventually can no longer walk. Then they are slaughtered and eaten. "

Return to Balkh

On December 27, 1051, Nāsir-i Chusrau reached Basra . He ran out of money, his clothes were tattered, his hair uncut and he couldn't pay the rental price of his camel for the journey. He was denied entry to the bath house where he wanted to wash himself. However, through good contact and the generous help of a vizier , he managed to obtain modest means. He put on new clothes and insisted on paying another visit to the bathroom, in which he had been treated so unworthily, and reading the embarrassed expressions of the servants, who now showed him respect. In the following, Nāser Khosrow describes the city in detail and explains the phenomenon of ebb and flow with which he comes into contact for the first time here on the Gulf coast.

In February 1052 he finally set sail on a ship the vizier had organized for him and went to Abadan . From there he continued his journey northwards via the city of Mahruban to Arragan. The next major city he now reached was Isfahan . Here he praises its good condition, the beautiful Friday mosque and the extensive infrastructure that is available to dealers and travelers here. “But in the whole country of Persian speakers I did not see a more beautiful, populous and flourishing city than Isfahan,” he concludes. He stays in town for 20 days and then travels on. Analogous to his brisk travel speed, Nāser Khosrow only briefly reports on the following stops on his journey. In Tabas he mentions how strict laws are exemplary in creating order and security: "Here no woman dares to speak to a strange man, and if one does, both are killed." He stayed for a while as the Prince's guest here before he moved on. On the way he was attacked by robbers, but got away unscathed. About Qa'in, Sarah and Merv he reached the end, in October of 1052 Balch .

Almost seven years had passed since he left. He immediately informed his brother, who had received no news from him, of his arrival. The Safarnāmeh ends with Nāsir-i Chusrau expressing the joy of having endured all the adventures well, thanking God for it and expressing his hope that he will be able to travel eastwards later.

Explanations

The Safarnāmeh as a regional historical source

It can be clearly seen that for Nāsir-i Chusrau not only his important, religiously motivated goals, the cities of Jerusalem , Cairo and Mecca count, but that the path is also of great importance to him. He describes the world he wanders through with curiosity and interest. When he is wondering about something or cannot explain something, he often asks or researches until he can find a satisfactory explanation. Therefore, the Safarnāmeh is today an important source and a rich fund for everyone who deals with the historical geography of the Middle East .

Since Nāsir-i Chusrau writes in Persian and primarily for a Persian audience, his descriptions of places are still very brief as long as he is on Persian soil. Instead, he has some nice interpersonal anecdotes to report here, which the reader should have found interesting, especially from the context of knowing his homeland. However, once it reaches the major trading centers of the Levant, that changes. Depending on their importance, he dedicates an almost systematic description to the individual cities, the most important points of which are always the water supply situation, the architecture of their mosques and the prices and supply of everyday items. As soon as he enters the sphere of influence of the Fatimids, the descriptions become more detailed and laudatory.

Despite this phenomenon, which is certainly also motivated by his own motives, his affiliation to the Ismaili Shia , the descriptions of Nāser Khosrow are always emphatically factual and correct in terms of content. If you try to understand his extremely detailed descriptions based on the current situation or in comparison with other historical sources, only minimal deviations arise. It is also noticeable that Nāser Khosrow names his sources for everything that he has not seen or experienced himself and even evaluates it if necessary. These two points also make the Safarnāmeh very credible with regard to descriptions for which no sources of comparison are available and make it an extremely valuable source in a culture in which vague or highly exaggerated information is not uncommon.

The Safarnāmeh as a mirror of the author's biography and views

In principle, direct personal comments by the author are very rare in Safarnāmeh - most of the book is described. At best, the author takes action to the effect that he travels from one place to another or learns something from others, which is then reproduced. At the end of the book, many questions about Nāser Khosrow's personal circumstances remain unanswered, such as his family situation. We don't know anything about a wife, children or other relatives except two brothers, or his financial situation. When it comes to his travel companions, he usually limits himself to speaking of us . Only towards the end of the book do we learn that one of his brothers and a servant are traveling with us, although it remains unclear whether there were any other fellow travelers.

However, there are some passages in the book where Nāsir-i Chusrau leaves the level of mere descriptive matter and starts talking about his own affairs. An important, if not the most crucial, passage is right at the beginning of the book. The author tells of his dream conversion and of his decision to leave for Mecca . It is interesting here that the reflections accompanying the conversion, which are only briefly touched upon in the Safarnāmeh, can be found in some of the poems of his divan. Here, however, he speaks of a long search that was accompanied by many disappointments, but ultimately led him to his goal. The dream is not mentioned in his poetic work. From the information we receive here, it can also be more easily concluded that Nāser Khosrow became Ismailit before he set out on his journey, while this remains open in Safarnāmeh.

The reports Nāsir-i Chusrau in Safarnāmeh also testify to a general piety along with a great admiration for the achievements of the Ismaili caliphate rather than formulating clear confessions or taking theological standpoints. What is more striking is the great tolerance that the author has towards foreign religions, for example when he describes the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem in detail or makes positive comments about the coexistence of a community of pagans on the Red Sea . The fact that his visit to Jerusalem must have been a memorable experience for Nāsir-i Chusrau can not only be guessed from the detail of his descriptions, but also from the fact that he was praying a prayer that he said in Jerusalem six years later Verbatim speech reproduces a technique that he uses very sparingly in Safarnāmeh.

Amazingly, these profound personal impressions from the holiest city, from Mecca, are almost completely absent. Although he stays here for a very long time, even working as a mosque servant, his descriptions remain very superficial.

On their journey across the Arabian Peninsula , the travelers ran into great financial difficulties. The reader does not learn the exact reasons for this, but the reports from this section of the trip are probably the most personal. The author reports on the adverse circumstances and worries of the trip and how one kept alive. Also interesting is the anecdote in which the traveling companions are thrown out of the bathhouse because of their neglected condition, only to return a few days later full of satisfaction like kings.

Nāsir-i Chusrau's concluding remark that he is planning a journey to the East with God's help remains the only indication of his subsequent missionary work.

At this point, however, it must be noted that all the surviving copies of the Safarnāmeh are significantly younger than the time of its creation. So it should not be ruled out that some, especially personal remarks relating to the Ismaili faith were left out or changed when copying, because they were no longer politically opportune, but the travel reports were still valued. In conclusion, however, this can no longer be judged from today's materials.

The Safarnāmeh and the Persian language

Safarnāmeh is also of great importance because of its influence on the development of the New Persian language . New Persian had developed centuries earlier through a mixture of Middle Persian with Arabic elements and, above all, with the spelling using the Arabic script , but for a long time it had only played a role as a more or less regional language, while Arabic was the dominant language of the Region was. The Persian-language literature of this time was largely limited to poetry. Today, Safarnāmeh is even considered to be the first major prose work in Neo-Persian, but at least as a work that had an exemplary effect on the developing prose literature of the subsequent period. For Nāser Khosrow it must have been a conscious decision to write his travelogue not in Arabic, but in Persian and a sign of the newly emerging Persian national understanding.

literature

- Nasir-i Husrau: Safarnama-i Nasir-i Husrau. Ed. Nadir Wazinpur, Tehran 1971.

- Nasir-i Husrau: name of the safari . Ed. Manfred Mayrhofer, trans. by Uto Melzer, Graz 1993.

- Jan Rypka : Iranian literary history. Leipzig 1959.

- Alice C. Hunsberger: Nasir Khusraw - The Ruby of Badakhshan. London 2000.

- Lutz Richter-Bernburg: Going places with Naser-e Khosrow and his translator. In: The World of Islam No. 33, Leiden 1993.

Individual evidence

- ↑ For all biographical information regarding Nāsir-i Chusrau see: Alice C. Hunsberger: Nasir Khusraw - The Ruby of Badakhshan. London 2000

- ↑ German translation cited from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 11.

- ↑ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 13.

- ↑ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 22.

- ^ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 40.

- ↑ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 49.

- ^ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 64.

- ^ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 75.

- ^ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 79.

- ↑ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed. Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 92.

- ↑ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed. Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 92.

- ↑ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 93.

- ^ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 97.

- ^ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed.Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 106.

- ↑ German translation quoted from: Husrau, Nasir-i, Safarname (ed. Mayrhofer, Manfred, trad. Von Melzer, Uto), Graz 1993, p. 107f.

- ↑ For comparison, see here mainly poem 242 of his divan.