Klingenberg clay mine

| Clay mine of the city of Klingenberg am Main | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| General information about the mine | |||

| Mining technology | Underground mining , opencast mining before the middle of the 18th century | ||

| Funding / year | 1,000–16,000 t | ||

| Funding / total | approx. 1.1 million t | ||

| Information about the mining company | |||

| Operating company | City of Klingenberg am Main | ||

| Employees | 5-77 | ||

| Start of operation | 1742 (1567) | ||

| End of operation | December 2011 | ||

| Successor use | Birds of prey station and retreat for bats | ||

| Funded raw materials | |||

| Degradation of | Special tone | ||

| Mightiness | 60 m | ||

| Greatest depth | 100 m | ||

| Geographical location | |||

| Coordinates | 49 ° 47 '4 " N , 9 ° 12' 9.4" E | ||

|

|||

| Location | Klingenberg am Main | ||

| local community | Klingenberg am Main | ||

| District ( NUTS3 ) | Miltenberg | ||

| country | Free State of Bavaria | ||

| Country | Germany | ||

The Klingenberg clay mine is located on the eastern outskirts of Klingenberg am Main on the edge of the Bavarian Spessart . Very high quality clay has been mined there since the middle of the 16th century . It is one of the oldest clay mines in Germany. The clay mining helped the city to great wealth. The clay mine was closed in 2011 after 270 years of mining for reasons of profitability .

Location and origin of the clay deposit

The Klingenberg clays are an isolated occurrence of Tertiary sediments in the middle of the red sandstone of the southwestern Spessart. It is located east of the city of Klingenberg near the Mechenhard / Schmachtenberg fork in the road . In the east-west direction it has an extension of about 150 meters, in the north-south direction it extends for a maximum of about one kilometer. The thickness of the clay deposit, which does not bite or only bites superficially on some slopes , is given as 45 to 60 meters. According to boreholes , its maximum base depth is 100 meters. The geology and formation of the Klingenberg clays are closely linked to those of the Schippacher clays located just a few kilometers to the north . Regional geologically, both deposits are located in the central area of the so-called Großwallstadt-Obernburger Graben, a subsidence zone in the southwest of the Spessart, the formation of which is presumably related to the tectonics of the Upper Rhine Graben, and in which, unlike the rest of the Spessart, extensive layers of the Middle and Upper Buntsandsteins and at least some Cenozoic sediments have been preserved.

The blades Berger Tone remained in this case in a relatively short section of a narrow, more or less north-south (Rhine) trending trench condition or half-trench within the Großwallstadt-Obernburger trench. According to a more recent (2006) hypothesis, the geological development begins with the gradual sinking of this ditch into a deeply tropical weathered red sandstone hull surface with pending red tones. In the resulting, initially relatively shallow depression, which reached from Klingenberg to Schippach, a lake formed. The surface water around the clay particles washed from the Röt weathering blanket and carried her into the pond, where they are in the form of clay mud at the bottom again deposed . It is precisely this sludge that is the starting material for the clays preferably mined in the Klingenberg deposit. Since the relief at that time was only weak and in the vicinity of the depression apparently no coarse-grained rocks except the red clays were exposed to the erosion , no “contamination” of the lake sediments by coarser material could occur. A pollen analysis from 2004 shows a late Oligocene age for the older layers of the Klingenberg clays (early Chattian , around 30 million years before today). From the Miocene onwards, the differentiation of the landscape increased: the rift structure with the Oligocene (and possibly also Miocene) deposits sank at least in sections or the neighboring terrain was increasingly raised. The weathering could no longer compensate for the tectonic movements of the clods in the region, so that the relief steepened. This presumably led to slurries of already settled clay sludge from the shallower, more peripheral areas of the depression into the actual trench. These rearrangements could explain the lack of fine stratification of the clays in the deposit. Dating of coal-bearing layers in the higher part of the Schippach deposit suggest that the lake silted up in the late Miocene, about ten million years ago. Due to uplift or insufficient subsidence, parts of the trench filling were then removed again. It is completely absent between Klingenberg and Schippach, and the lack of equivalents of the "Schippach sands" between the Oligocene clays and the coarser, predominantly Quaternary cover layers (debris from sandstone rubble and fluvial loess and loess loam) in the Klingenberg deposit gives evidence of a considerable deposit there Shift gap .

history

According to oral and written records, a heavy thunderstorm in a side valley of the Seltenbach exposed clay in the western area of the deposit . This clay, which is easy to dig, served the potters in the area as a raw material . The first documentary mention of the clay mining was in 1567 in the Juristdictionalbuch as "Lettongrube", whereby the city of Klingenberg is shown as its owner. In 1685, the rent paid for the excavations was a major part of the city's assets.

Excavations 1740–1786

The mining of the clay first began with simple excavations near the surface. From 1740 about 21 pits are known where clay was extracted in the opencast mine . The pits had a width and length of about three to five meters and were up to 16 meters deep. Rain and meltwater ran into the pits and the low water permeability of the clay prevented it from flowing off. Together with the mountain pressure , there were collapses that had to be restored at great expense. The clay was probably extracted from the pits with hand reels . In order to prevent the pits from being constantly closed, pit 16 was lined with wood and the lower area was connected to the other pits. This is how the first shaft (also called the light hole) was created. Most of the clay mined until 1786 was processed by potters.

Underground mining from 1786

In 1785, Professor Pfeiffer, Hofrat von Mainz , suggested that the deeper, finer layers should also be dismantled and used in the porcelain and glass industries . In 1786, a main tunnel for drainage was created on the southwestern edge of the deposit, which was used for running in and for ventilation until the end of mining .

The ownership changed constantly at this time. In some places, the mining was limited to the promotion of the best clay quality, while the technical rules of mining for regulated and sustainable mining were often ignored. In 1798 the city of Klingenberg withdrew the lease from two tenants and took over the mine on its own. Due to the effects of the Napoleonic Wars , however, profits fell significantly and the city was forced to lease the mining rights again.

With the advancement of industrialization, clay became more popular again. On June 26, 1855, the city requested in a letter to the Royal Bavarian Government that the mine should be taken over under its own control. In a 30-page report, she accused the tenants of "overexploitation and desolation of the mine" and relied mainly on reports from the Orb Mining Authority. The government complied with this request and approved the takeover on November 29, 1855. Nevertheless, it was not until 1859, after numerous legal disputes with the tenants, that the city was able to take over the operation of the clay mine again.

Just one year later the “golden years” of clay mining began for the city. The mine generated a surplus of 8,221 guilders in 1860. This was more than double the previous rent. The net profit could be increased further and further. In 1907 it was 220,000 and in 1912 even 325,000 marks. The income allowed the city to forego the collection of taxes and levies and to modernize the place. In 1866, she built a Mainbad, and in 1874/75 a cemetery and a mortuary were added. In 1880 the income was even enough for the construction of its own bridge over the Main (210,294 marks). A new school was added in 1882 (27,257 marks) and in 1885/86 a new town hall (40,205 marks). The reconstruction of the church between 1889 and 1892 cost 162,199 marks. In addition, between 1893 and 1899 water pipes and sewers (188,689 marks), an own power station and a slaughterhouse (340,436 marks) were built. Smaller projects, such as the civil service building (52,861 marks), a children's school (17,111 marks) and the conversion of the old town hall into a post office (22,137 marks) followed between 1901 and 1906 and paid out 400 marks a year.

After the First World War , mining in Klingenberg initially suffered from the consequences of the lost war. The same was true for the time of the subsequent global economic crisis . From 1938 the clay mine achieved an upswing through consistent planning. At the beginning of the Second World War , many workers were drafted and only through the use of prisoners of war from the Soviet Union was it possible to increase the sound production. In the last days of the war, the mine tunnel offered many Klingenbergers protection from tank shells and low-flying aircraft.

After 1960, sales of the clay produced fell markedly. The city decided to rationalize while reducing the number of employees. Most recently, the workforce numbered nine people, six of whom worked underground. After further rationalization was no longer possible, the losses increased significantly, especially since renowned customers such as the pencil manufacturer Faber-Castell jumped out. In the crisis year 2009, the annual production was reduced from 3000 to only 960 tons. The city council decided to close the mine. As a result, sales doubled in the short term as the remaining customers filled their warehouses. In December 2011 the last clay was extracted in the mine. In 2012 security and safekeeping work was carried out on the company premises.

Mining technology

Conveyor technology until 1939

Until the beginning of the 20th century, the clay was extracted entirely by hand. The deposit was developed from the western edge, where the clay was closest to the surface, and followed the fall of the clay deposit into the depth . The shafts were right in the clay deposits geteuft , that went completely into the clay layer. This had the advantage that the valuable clay was already extracted when the shaft was being built. On the other hand, the dismantling took place without observing the necessary shaft safety pillars. Although the shaft was lined with wood, the lateral pressure was already noticeable after about six to eight weeks and the shaft had to be reworked. If the maintenance became too expensive, the shaft was closed and a new one was built. The first four shafts were about 40 m deep. By 1938, 20 shafts had been sunk, some of which reached up to 66 m deep.

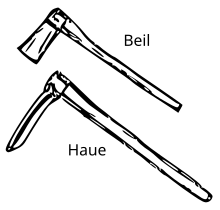

The miner ( Hauer ) made vertical and horizontal slits about 20 cm deep with his ax at the end of a mining section . Then he broke the approximately 5 kg heavy clay blocks out of the wall with a pick . To adhesion of the clay on gezähe to prevent the tool was periodically immersed in a water-filled timber bucket.

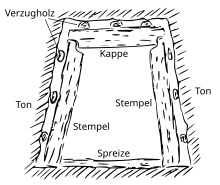

Once the mining section had been driven about 80 cm, the pit was built using wooden door frames . The laterally arranged punches were slightly inclined to each other and had a length of about 2 m. The approximately 1.2 m long cap rested on the stamps , whereby a leaf on the cap and an approximately 1.40 m long spreader on the bottom prevented mutual displacement and thus a narrowing of the cross-section of the route. The door frames were placed at a distance of about 50 cm. Tension timbers , which were arranged in the direction of the route behind the punches or above the caps, were used for further protection and were intended to reduce the penetration of the clay by the rock pressure . An extension of the line by one meter produced around 15 tons of clay.

On a level stretch of road hauliers (also known as cart runners) removed the clods with wheelbarrows. Narrowed cross-sections of the route had to be overcome in a stooping position while carrying or throwing the clods backwards through the legs. The miners transported the clods to around 10 m in front of the shaft. Slinger loaded the conveyor tons up to 25 clods, which are then passed on to the shaft surface were drawn. It was not until 1902, after the power station had been built in 1897, that the shaft production was switched to electric motor operation. Clay fragments could not be conveyed in this way. The material, the so-called lump earth, was placed in backfill sites and solidified there by the rock pressure. After 6 to 7 years the clay could be recovered as clods.

Over the course of the day , miners and women sorted the clods of clay on the hanging bench according to quality. Horse-drawn vehicles and later a truck, the “Tonauto”, brought the clods from the pit to the storage cellars at the town hall or to the banks of the Main, where they were partly packed in wooden barrels and loaded onto ships. Later the clay blocks were taken away by train .

Strategic changes after 1939

The enormous pressure of the mountains resulted in very high maintenance and repair costs for shafts and routes. The then operations manager, Barthel, carried out numerous serious changes to increase efficiency. This also included reversing the mining direction from east to west. A new production blind shaft (shaft 21) with a cross-section of 3.5 m × 1.5 m was sunk completely in the adjacent red sandstone to a depth of 60 meters in the east. From there, straightening routes led to the south and north in the sandstone . These also ran in the red sandstone and for the first time contained tracks (track spacing 50 cm) on which trolleys ( Hunte ) with a capacity of 0.5 tons were used. Starting from the straightened sections, mining sections were led into the clay at intervals of 15 to 20 meters. Cart mining continued to prevail here until 1955.

Demand increased significantly as a result of the war, but the amount that could be mined by hand was limited. Attempts to dismantle by blasting were discarded after the first tests, as the vibrations had a negative effect on the dismantling and the mine weather deteriorated significantly. In 1951, however, attempts with pneumatic hammers were successful , a technique that was retained until the end of the clay extraction. The compressed air came from compressors above ground. Shift capacities of 6 to 10 tons could be achieved with the pick hammer.

In 1955 the blind shaft was sunk a further 12 m. The result was in addition to the 60 m- sole a 70-m level. At the same time, the mining routes were driven with an incline of 15 degrees (profile 1.8 m × 1.5 m). The falling clods of clay slid down the mining section on wooden chutes and were pulled directly into the conveyor hunt on the base section. The conveyor frame in the blind shaft could accommodate the full hunt and transport it upwards. A track led from the hanging bank in the day tunnel to the mouth hole and further over a bridge to the head of the bunker system, where the sound was tipped separately according to quality levels. The trucks were loaded directly at the bunker.

As the deposit had developed a very high degree of development over the years, a new mining method had to be used to effectively extract the remaining deposits from the 70 m level. The clay mining now took place according to the principle of broken piers. The main conveyor line, from which the mining line branched off at the side, was built with steel arches. It had a length of about 15 m and was secured by wooden door frames with a construction distance of 50 cm. After reaching the full length, starting from the end, the route was expanded on one side in the demolition to a width of 3.5 m (chamber). The door frames were stolen and replaced by individual stamps with head wood at a distance of 0.8 to 1 m. The chamber construction ended about 3 m before the conveyor line. This last area served as a safety pillar for the conveyor line. During the dismantling process, the more distant stamp structures were gradually robbed and the unsecured chamber was gradually broken into. After three to four months, the cavity was completely blocked. The next upgraded line could then be constructed at a distance of around 6 m.

Clay types and properties

The refractory binding clay mined in Klingenberg is characterized by great homogeneity . The rational analyzes from 1988–2001 resulted in the following average values : clay (84%), quartz (8.5%), feldspar (7.5%). The average chemical analysis of the clay for the years 1992–2001 showed: Alumina ( aluminum oxide ) Al 2 O 3 30.4%, silica (SiO 2 ) 51.2%, magnesium oxide (MgO) 0.85%, calcium oxide (CaO) 0.63%, iron oxide (Fe 2 O 3 ) 3.03%, potassium and sodium oxide (Na 2 O / K 2 O) 1.2%, titanium oxide (TiO 2 ) 1.2%, loss on ignition 11.3% .

The tone is light to dark gray, occasionally black gray to black. The darker color is due to the higher humus content . The raw material is very fatty and only softens slowly in water. The clay has a high plasticity and thus a high degree of dry shrinkage, so that it tends to crack without lean additives. In the fire, the clay shows very early sintering , which is practically complete at 1100 ° C. The firing color is yellowish-white to yellowish depending on the temperature.

The Klingenberger clay is divided into different types, which differ in the clay substance. The basic type A embodies weakly silty clays with clay contents of 84–94%, the basic type B embodies strongly clayey fine to medium silt with clay contents of 34–47%. The different clay types were again offered in four degrees of fineness: raw clay, clay chips, clay granules and clay powder.

use

The pencil clay has an excellent bond with graphite and has therefore been exported for pencil production to Europe, North and South America, Japan , India , Iran , Korea , Pakistan , Taiwan , Thailand and Mexico , among others . The special type was part of precious metal and graphite crucibles, technical ceramics for the electrical industry, glazes in fine ceramics and some abrasives . The remaining varieties were mainly sold to ceramic factories, paint factories and modeling schools.

Around half of the 3000 tons extracted at the end of the 20th century were exported abroad.

Protection status and current usage

The underground clay extraction in the mine is designated as a protected geotope by the Bavarian State Office for the Environment under the geotope number: 676G001 .

Due to the sinking clay masses during centuries of mining, a depression up to twelve meters deep had formed above ground, in which surface water collected and a pond was created. While the mine was in operation, the water was pumped into the adjacent Rauschenbach. With the cessation of operations, a 145 m long underground water overflow into the next valley was created. The surface of the subsidence area including the pond should develop into a biotope .

The Klingenberg bird of prey station was built on the site of the clay mine. The former office and the common rooms of the miners were converted into an information center by the State Association for Bird Protection in Bavaria . In 2014, seven aviaries were created to house and care for injured birds of prey . The bird of prey station is the central point of contact for natural history excursions and adventure hikes. In the actual clay mine, the old tunnel entrances and operating facilities were provided with openings during the dismantling , so that retreats for bats were created. The bird of prey station was officially opened on April 10, 2016.

Local museum

The exhibition in the Viticulture and Local History Museum of the city of Klingenberg shows two show tunnels. The branch on the right shows the dismantling with a hatchet and a grave, as well as the removal via wheelbarrows. The branch on the left shows the removal of the clay clods with the help of the mine car ( Hunt ). The exhibition also contains graphics and photos on the origins of the clay deposits.

literature

- Eckhard Ehrt: Tonwerk operating history for the city of Klingenberg am Main . Ed .: BIT Tiefbauplanung GmbH. Klingenberg 2013.

- Eckhard Ehrt: 270 years of Klingenberg a. Main - an overview of the technical and historical development . In: Ring Deutscher Bergingenieure e. V. (Ed.): Mining . 65th year, no. 5 . Makossa Print and Media, 2014, ISSN 0342-5681 , p. 203–213 ( rdb-ev.de [PDF; accessed on March 6, 2016]).

- Eckhard Ehrt: The Klingenberg am Main clay mine . In: Spessart. Monthly magazine for the cultural landscape . 101st year, issue 12 (December). MainEcho, Aschaffenburg December 2007, p. 17-24 .

- D. Melzer, E. Ehrt: The clay from Klingenberg am Main - a specialty of the malleable silica raw materials . In: Ceramic magazine . tape 54 . Expert Fachmedien, Düsseldorf 2002, p. 952-955 .

Web links

- Tonwerk of the city of Klingenberg a. Main , official website of the city of Klingenberg, accessed on November 23, 2015

- Joachim Lorenz: The former clay mine (underground!) (1567) 1742–2011 and the Seltenbach Gorge near Klingenberg am Main , description including inspection report, accessed on November 27, 2015

- Jürgen Schreiner: One last lucky run at a depth of 70 meters. (PDF) Main-Echo, 2011, accessed on February 28, 2016 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Pencil tone. (PDF) Westerwald-Ton e. V, TonLeiter ABC, p. 28; accessed on November 23, 2015

- ↑ a b c Eckhard Ehrt: Operating history of the Tonwerk of the city of Klingenberg am Main . Ed .: BIT Tiefbauplanung GmbH. Klingenberg 2013.

- ↑ a b c Underground clay mining E von Klingenberg, geotope number: 676G001. (PDF) Bavarian State Office for the Environment, as of May 21, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d e f Eckhard Ehrt: The Klingenberg clay mine on the Main . In: Spessart. Monthly magazine for the cultural landscape . 101st year, issue 12 (December). MainEcho, Aschaffenburg December 2007, p. 17-24 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Eckhard Ehrt: 270 years of clay mine Klingenberg a. Main - an overview of the technical and historical development . In: mining . 65th year, no. 5 , 2014, ISSN 0342-5681 , p. 203–213 ( complete volume [PDF; 11.0 MB ]).

- ↑ a b c Jürgen Jung: GIS-supported reconstruction of the neogene relief development of tectonically influenced low mountain ranges using the example of the Spessart (NW Bavaria, SE Hessen). Dissertation, University of Würzburg, 2006, urn : nbn: de: bvb: 20-opus-20961

- ↑ a b Eckhard Ehrt: History of the Klingenberger Tonwerk. City of Klingenberg am Main, accessed on November 29, 2015 .

- ↑ a b From the gold mine to the debt trap. Review: The checkered history of clay mining in Klingenberg - "Letton pits" first attested in 1567, underground mining since 1742. In: Source: 250 years of clay mine Klingenberg a. Main, Klingenberg 1992. Main-Echo, December 7, 2011, accessed November 29, 2015 .

- ↑ a b chronicle of the city Klingenberg am Main, Volume II. (PDF, 56MB) City Klingenberg am Main, 1995, pp 22-30 , accessed on 29 November 2015 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Chronicle of the City of Klingenberg am Main, Volume III. (PDF; 56MB) City of Klingenberg am Main, 1996, pp. 237–253 , accessed on November 29, 2015 .

- ↑ Dr. Mockery: The municipal clay mine near Klingenberg, operating documents. 1876, archive of the city of Klingenberg am Main: “We see several miners, clods of clods in their arms twisted downwards, rushing past us. The promotion work is often very tedious, namely when it has to be done through squashed places. The transporter must pass such in a stooped position or throw the clods to his comrade through the narrow opening. Sometimes the latter is best done in an inverted, bent posture backwards between the legs. A transporter can move 2000 clods a day. "

- ↑ a b Eckhard Ehrt: Quality. City of Klingenberg am Main, accessed on November 29, 2015 .

- ↑ Klingenberg bird of prey station. (No longer available online.) LBV, archived from the original on December 17, 2015 ; accessed on November 27, 2015 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Harald Krug: Klingenberg, Wine and Local History Museum. City of Klingenberg, accessed on November 27, 2015 .