Walking leaves

| Walking leaves | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

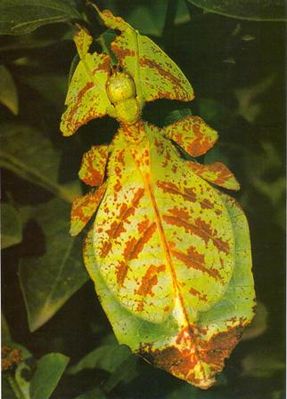

Phyllium bioculatum , female |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the superfamily | ||||||||||||

| Phyllioidea | ||||||||||||

| Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893 | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the family | ||||||||||||

| Phylliidae | ||||||||||||

| Brunner von Wattenwyl, 1893 | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the subfamily | ||||||||||||

| Phylliinae | ||||||||||||

| Kirby , 1904 |

The Walking Leaves form a subfamily (Phylliinae) within the order of the ghost horror . Since this subfamily is the only one of the Phylliidae family and this in turn is the only one of the superfamily Phyllioidea, the walking leaves are often equated with these taxa .

features

The species of the walking leaves can reach body sizes between 24 ( Microphyllium spinithorax ) and 120 millimeters ( Phyllium giganteum ) in length. They are characterized by a horizontally, leaf-like broadened body, which camouflages it as a leaf ( mimetic ). The legs are also optimally adapted to this leaf mimicry through leaf-like extensions ( lobes ). Walking leaves are more or less green, yellow, brown or reddish, depending on their type and origin. There are speckled and almost monochrome representatives. Some species are so variable in terms of their color that they have often been described several times (e.g. Phyllium bioculatum ), which has led to a corresponding number of synonyms .

The females are more like leaves than males. They owe this to their very broad abdomen and short mesonotum . In addition, the forewings of adult females are usually only developed as foliage-like cover wings ( tegmina ), which often cover the entire abdomen. Hind wings (alae) are only developed in the previously known females of the celebicum species group, i.e. in Phyllium athanysus , Phyllium celebicum , Phyllium ericoriai , Phyllium rarum , Phyllium tibetense and Phyllium westwoodii . The narrower and smaller males usually have short fore wings and fully developed, mostly transparent hind wings, which enable them to make short flights. On the vertex between the complex eyes, there are usually three individual eyes ( ocelles ). Their antennae are significantly longer than those of the females and have bristles. They consist of 20 to 26 limbs, those of the females only reach the length of the head and always consist of nine limbs. They are transformed into stridulation organs . The abdomen is made up of ten abdominal segments , of which the nine posterior segments are free and the first is fused with the hind chest ( metanotum ). A transverse furrow on the underside shows the transition between the metanotum and the first abdominal segment. At the end of the eighth abdominal segment lies the subgenital plate , under which the genital opening and the opening for the ovum exit are located.

distribution

The distribution area of the recent Walking Leaves extends from the Seychelles to Southeast Asia and the Chinese provinces of Hainan , Guangxi , Yunnan and Tibet to Melanesia . While the species of the genus Phyllium can be found throughout the range, the occurrence of the Chitoniscus species is limited to Melanesia, that of Microphyllium to the Philippines and that of the Nanophyllium species to New Guinea . Some phyllium species inhabit a surprisingly large area. The distribution area of Phyllium bioculatum extends in the west to the Seychelles and Mauritius , in the east and south to Malaysia , Sumatra , Borneo and Java and in the north via India , Sri Lanka to China. Due to the large area of distribution, these species have formed local forms that differ in terms of body structure and color. In the case of Phyllium bioculatum and other species with a large distribution area, the origin (if this is known) and typical morphological features are also listed (for example: with a pointed abdomen).

Way of life

Food and camouflage

Walking leaves are herbivorous insects whose food is the leaves of still unknown tropical plants, but also those of guava , cocoa , myrtaceae , mango and tea . They imitate their leaves not only in their appearance, but also in their behavior. The animals are nocturnal, during the day they remain completely motionless for hours. When disturbed, they mimic a leaf moving in the wind by rocking and camouflaging themselves from potential predators. It is very likely that these behaviors were already pronounced millions of years ago, as findings from fossils from the Eocene suggest.

Defense behavior

The females of most Faering leaves with their antennas to a Abwehrstridulation capable. The males of different species tend to shed their legs ( autotomy ) in order to distract predators. From Phyllium celebicum and Phyllium bilobatum is known to have featured defensive glands that make it through stigmenähnliche openings in the pronotum a milky, pungent-smelling, corrosive defensive secretions may spatter. When disturbed, the females also stridulate with their antennae. The main strategy of all walking leaves is the most perfect leaf mimesis (phytomimesis) possible.

Reproduction

Walking leaves, like most ghosts, are capable of parthenogenetic reproduction. If there are males, the females mate with them, depending on the species, about two to four weeks after molting to form the imago . The males perceive the vibrations of the stridulating females with their feelers and follow them to the females. When mating, the male pushes the sperm carrier ( spermatophore ) under the subgenital plate of the female, where it empties itself before it falls off. The females begin to lay eggs three to four weeks after the last moult. The one to three eggs per week are either dropped on the floor or thrown away with a jerky movement of the abdomen. In this way, 100 to 300 eggs are laid per female, depending on the species.

The eggs are so different from one another that they are often used as the only reliable identifier to differentiate between species. They partly resemble plant seeds . The eggs of Phyllium caudatum resemble the seeds of rhubarb and those of Phyllium giganteum resemble those of the miracle flower . In addition to eggs without attachments, there are often those with characteristically arranged, feather-like bristles. These are usually long, closely standing, branched and interlocked or grown together. When the eggs are freshly laid, they are still close to the surface of the egg and only roll out after being laid when the humidity is appropriate. The lid ( operculum ) of such eggs is often surrounded by a wreath of bristles. In other species, the lid can sit on the egg like a hat. Usually structures such as holes or grooves are present on the partially fine to coarse-pored surface of the eggs, which are also typical of the species. The shape of the eggs can be determined by edges and keels, so that they can appear rectangular , square , pentagonal or star-shaped in cross-section . The micropylar plate is usually spindle-shaped, with the micropyle towards the lower pole and the shape becoming somewhat wider (see also the construction of the phasmid egg ).

The very conspicuous nymphs hatch after four to eight months by pressing the lid open with their heads. They are drawn in red, red-brown or black-brown and often appear even more noticeable due to white spots. Before eating for the first time, they run very quickly over the food plants, striving upwards. After a few days, they adopt the way of life of their parents and turn increasingly green. The development of the adult insect takes four to eight months, depending on the species, with the males moulting four times and the females six times. The old skin exuvia is usually eaten up after moulting because it contains important trace elements . In many species, the color depends on the environmental conditions (especially humidity and temperature, but also food and light).

Terrarium keeping

Only a few species are kept in the terrariums of enthusiasts. There are only seven species on the Phasmid Study Group's list of cultures . The species that are cared for come more or less into fashion depending on availability and husbandry requirements. In the early 1990s, Phyllium bioculatum and then parthenogenetically grown Phyllium giganteum were bred. Thereafter, Phyllium westwoodii appeared under the name of the similar Phyllium celebicum . Phyllium philippinicum is now the most common species in terrariums. Occasionally, today also Phyllium bilobatum , the first as Phyllium siccifolium addressed Phyllium hausleithneri and finally ericoiai Phyllium , Phyllium jacobsoni , Phyllium mabantai and also the real Phyllium celebicum to find lovers.

Terrariums that are taller than wide are better suited to keeping these ghosts (from 60 centimeters high), as the animals tend to move vertically. Narrow-necked water-filled vases with the forage plants ( blackberry , raspberry , rose , oak or guava branches ) are placed in these containers , the leaves of which are eaten by the insects. When feeding roses, the origin of which is unknown, there is a risk that the animals will poison themselves with insecticides . Dried or moldy branches must be replaced. The twigs are sprayed with water two to three times a week, the dosage being chosen so that the water droplets are dry after a few hours. The humidity should be between 60 and 80 percent, the temperature between 20 and 30 ° C (for most species better 25 ° C and more). Ensure good ventilation. For this purpose, small fans (computer fans) have proven themselves, which provide air movement for a few minutes every hour at a distance in front of the ventilation grille of the terrarium. Lighting can be beneficial for the shelf life of the forage plants. There are two options for setting up the terrarium with substrate. On the one hand, the floor can be covered with kitchen paper, which is changed regularly. On the other hand, a slightly damp, but never wet, sand-potting soil mixture can also be introduced. If it forms on this mold, the settlement of springtails makes sense, which feed on it and thus destroy it. Springtails can either be purchased in the animal feed department of the well-stocked pet shop or brought into the terrarium together with their natural substrate, namely appropriately populated forest floor.

There are the following options for breaking the eggs. Eggs placed on a mixture of sand and potting soil can be left on the ground if it is ensured that mold does not develop. The eggs can also be collected and matured in an incubation container under controlled environmental conditions (temperature and humidity).

Fossil finds

In 2005, a 47 million year old fossil walking leaf was found in the Messel pit . It was described by Wedmann , Bradler and Rust in 2007 as Eophyllium messelensis and shows that the range of the walking leaves was once much larger and was not limited to Southeast Asia as it is today. The fossil is extremely well preserved and is also very similar to fossil leaves from the Messel pit found earlier. Its abdomen is laterally widened and therefore looks like a leaf. The fossil resembles the males of the walking leaves living today and, in addition to similarities in terms of size and other external features, also shows small differences, such as in the reproductive system.

Systematics

External system

The Phyllioidea are one of four superfamilies of the suborder Areolatae . In this there is only one family and that of the Phylliidae with again only one subfamily, the Phylliinae.

Internal system

In addition to the fossil genus Eophyllium, the subfamily Phylliinae now includes five recent genera in two tribes .

Tribus Phylliini Brunner von Wattenwyl , 1893

-

Chitoniscus Stål , 1875Chitoniscus sarrameaensis , female from the collection of D. Großer

- Chitoniscus brachysoma ( Sharp , 1898)

- Chitoniscus erosus Redtenbacher , 1906

-

Chitoniscus feejeeanus ( Westwood , 1864)

( Syn. = Phyllium novaebritanniae Wood-Mason , 1877) - Chitoniscus lobipes Redtenbacher , 1906

- Chitoniscus lobiventris ( Blanchard , 1853)

- Chitoniscus sarrameaensis Greater , 2008

-

Microphyllium Zompro , 2001

- Microphyllium haskelli Cumming , 2017

- Microphyllium pusillulum ( Rehn, JAG & Rehn, JWH , 1934)

- Microphyllium spinithorax Zompro , 2001

Four sub-genera are distinguished within the genus Phyllium . In addition to Phyllium itself, there is the sub-genus Pulchriphyllium , established by Griffini in 1898 , to which, among other things, the Great Walking Leaf belongs. In the full zoological name for representatives of sub-genera, their name can be put in brackets between the generic and species names. The Great Walking Leaf can also be called Phyllium (Pulchriphyllium) giganteum . For the sake of clarity, the purely binary nomenclature is retained in the following , i.e. the sub-genus is not added. The Great Walking Leaf is here called Phyllium giganteum . With Comptaphyllium and Walaphyllium , two further subgenera were described in 2019 and 2020. In addition to the sub-genre classification, Hennemann et al. also the division into groups of species, some of which have been continued by the following authors and are also shown here:

- Subgenus Phyllium

-

-

celebicum species groupPhyllium ericoriai , pair

- Phyllium athanysus Westwood , 1859

- Phyllium bonifacioi Lit & Eusebio , 2014

- Phyllium celebicum De Haan , 1842

- Phyllium ericoriai Hennemann , Conle , Gottardo & Bresseel , 2009

- Phyllium oyae Cumming & Le Tirant , 2020

- Phyllium parum Liu , 1993

- Phyllium rarum Liu , 1993

- Phyllium tibetense Liu , 1993

- Phyllium westwoodii Wood-Mason , 1875

- Phyllium yunnanense Liu , 1993

-

celebicum species group

-

-

siccifolium species group

Phyllium jacobsoni , pair

Phyllium jacobsoni , pair

-

siccifolium species group

-

- Phyllium bilobatum Gray, RG , 1843

- Phyllium bourquei Cumming & Le Tirant , 2017

- Phyllium brossardi Cumming , Le Tirant & Teemsma , 2017

- Phyllium drunganum Yang , 1995

- Phyllium conlei Cumming , Riquelme & Teemsma , 2018

- Phyllium elegans Larger , 1991

- Phyllium fallorum Cumming , 2017

- Phyllium gantungense Hennemann , Conle , Gottardo & Bresseel , 2009

- Phyllium gardabagusi Cumming , Bank , Le Tirant & Bradler , 2020

- Phyllium geryon Gray, RG , 1843

- Phyllium hausleithneri Brock , 1999

- Phyllium jacobsoni Rehn, JAG & Rehn, JWH , 1934

- Phyllium letiranti Cumming & Teemsma 2018

- Phyllium mabantai Bresseel , Hennemann , Conle & Gottardo , 2009

- Phyllium mamasaense Greater , 2008

- Phyllium mindorense Hennemann , Conle , Gottardo & Bresseel , 2009

- Phyllium nisus Cumming , Bank , Le Tirant & Bradler , 2020

- Phyllium palawanense Larger , 2001

- Phyllium philippinicum Hennemann , Conle , Gottardo & Bresseel , 2009

- Phyllium rayongii Thanasinchayakul , 2006

-

Phyllium siccifolium ( Linnaeus , 1758)

(syn. = Phyllium brevicorne Latreille , 1807)

(syn. = Phasma chlorophyllia Stoll , 1813)

(syn. = Phasma citrifolium Lichtenstein , 1796)

(syn. = Phyllium donovani Gray, RG , 1835)

( Syn. = Mantis foliatus Perry , 1811)

(Syn. = Gryllus folium lauri Linnaeus , 1754)

(Syn. = Phyllium gorgon Gray, RG , 1835)

(Syn. = Phyllium stollii Lepeletier & Serville , 1825) - Phyllium telnovi Brock , 2014

- Phyllium tobeloense Bigger , 2007

- Phyllium woodi Rehn, JAG & Rehn, JWH , 1934

- Without assignment to a species group:

-

-

- Phyllium antonkozlovi Cumming , 2017

- Phyllium arthurchungi Seow-Choen , 2016

- Phyllium bradleri Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium chenqiae Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium chrisangi Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium cummingi Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium rubrum Cumming , Le Tirant & Teemsma , 2018

- Subgenus Pulchriphyllium Griffini , 1898

-

- bioculatum species group

-

Phyllium bioculatum Gray, RG , 1832

(Syn. = Phyllium agathyrsus Gray, RG , 1843)

(Syn. = Phyllium crurifolium Serville , 1838)

(Syn. = Phyllium dardanus Westwood , 1859)

(Syn. = Phyllium gelonus Gray, GR , 1843 )

(Syn. = Phyllium scythe Gray, RG , 1843)Phyllium giganteum , female - Phyllium giganteum Hausleithner , 1984

-

Phyllium pulchrifolium Serville , 1838

(Syn. = Phyllium magdelainei Lucas , 1857) - Phyllium sinense Liu , 1990

-

Phyllium bioculatum Gray, RG , 1832

- schultzei species group

- Phyllium exsectum Zompro , 2001

- Phyllium schultzei Giglio-Tos , 1912

- frondosum species group

- Phyllium asekiense Bigger , 2002

- Phyllium chitoniscoides Greater , 1992

- Phyllium frondosum Redtenbacher , 1906

- Phyllium groesseri Zompro , 1998

-

Phyllium keyicum Karny , 1914

(Syn. = Phyllium insulanicum Werner , 1922)

(Syn. = Phyllium indicum Günther , 1929) - Phyllium suzukii Bigger , 2008

- brevipenne species group

- Phyllium brevipenne Bigger , 1992

- Without assignment to a species group:

-

-

- Phyllium abdulfatahi Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium agnesagamaae Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium detlefgroesseri Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium fredkugani Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium lambirensis Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium maethoraniae Delfosse , 2015

- Phyllium mannani Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium rimiae Seow-Choen , 2017

- Phyllium shurei Cumming & Le Tirant , 2018

- Subgenus Comptaphyllium Cumming , Le Tirant & Hennemann , 2019

- Phyllium caudatum Redtenbacher , 1906

- Phyllium regina Cumming , Le Tirant & Hennemann , 2019

- Phyllium riedeli Kamp & Hennemann , 2014

- Phyllium lelantos Cumming , Thurman , Youngdale & Le Tirant , 2020

- Phyllium monteithi Brock & Hasenpusch , 2002

- Phyllium zomproi Greater , 2001

-

Pseudomicrophyllium Cumming , 2017

- Pseudomicrophyllium faulkneri Cumming , 2017

Tribus Nanophylliini Zompro & Grösser , 2003

-

Nanophyllium Redtenbacher , 1906

- Nanophyllium adisi Zompro & Grösser , 2003

- Nanophyllium australianum Cumming , Le Tirant & Teemsma , 2018

- Nanophyllium hasenpuschi Brock & Grösser , 2008

- Nanophyllium larssoni Cumming , 2017

- Nanophyllium pygmaeum Redtenbacher , 1906

- Nanophyllium rentzi Brock & Grösser , 2008

- Nanophyllium stellae Cumming , 2016

In 1815 Thunberg introduced the generic name Pteropus for the species Phyllium siccifolium, which was called Phasma siccifolia at the time . This name was already occupied by a genus of the actual flying foxes ( Pteropus Erxleben , 1777), so that it was no longer available for the description of other genera according to the international rules for zoological nomenclature . Since Phasma siccifolia was later assigned to the genus Phyllium, which was first mentioned in 1798 (first mentioned as Phyllium siccifolium in 1825), this name is to be regarded as a synonym for the subgenus Phyllium in relation to walking leaves .

photos

Phyllium westwoodii , males with characteristic retracted antennae

Phyllium hausleithneri , female from the collection of D. Großer

Phyllium asekiense , female from the collection of D. Großer

Phyllium ( Pulchriphyllium ) spec., Nymph with regenerated right foreleg

swell

- ↑ a b c d e f g Detlef Larger : Wandering sheets , Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-930612-46-8

- ↑ a b Christoph Seiler, Sven Bradler, Rainer Koch: Phasmids - care and breeding of ghosts, stick insects and walking leaves in the terrarium . bede, Ruhmannsfelden 2000, ISBN 3-933646-89-8

- ↑ a b c Frank H. Hennemann , Oskar V. Conle , Marco Gottardo & Joachim Bresseel : Zootaxa 2322: On certain species of the genus Phyllium Illiger, 1798, with proposals for an intra-generic systematization and the descriptions of five new species from the Philippines and Palawan (Phasmatodea: Phylliidae: Phylliinae: Phylliini) , Magnolia Press, Auckland, New Zealand 2009, ISSN 1175-5326

- ↑ Detlef Larger: Basic Knowledge of Walking Leaves - Biology - Keeping - Breeding . Sungaya Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-943592-18-4

- ↑ Phasmid Study Group List (English)

- ↑ Ingo Fritzsche : Poles - Carausius, Sipyloidea & Co. , Natur und Tier Verlag, Münster 2007, ISBN 978-3-937285-84-9

- ^ Sonja Wedmann, Sven Bradler and Jes Rust: The first fossil leaf insect: 47 million years of specialized cryptic morphology and behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104 (2) 565-569, doi : 10.1073 / pnas.0606937104

- ^ Science ticker

- ^ Paul D. Brock , Thies H. Buescher & Edward W. Baker: Phasmida Species File Online . Version 5.0. (accessed on June 12, 2020)

- ^ Royce T. Cumming , Sierra N. Teemsma & Pablo Valero Riquelme : Description of Phyllium (Phyllium) conlei, new species, and a first look at the Phylliidae (Phasmatodea) of the Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia . Insecta mundi. Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc., Gainesville, FL USA. 2018

- ^ Royce T. Cumming, Stéphane Le Tirant & Frank H. Hennemann: Review of the Phyllium Illiger, 1798 of Wallacea, with description of a new subspecies from Morotai Island (Phasmatodea: Phylliidae: Phylliinae) , Faunitaxys, 7 (4), Saint -Etienne, 2019: 1 - 25.

- ^ Royce T. Cumming, Jessa H. Thurman , Sam Youngdale & Stephane Le Tirant: Walaphyllium subgen. nov., the dancing leaf insects from Australia and Papua New Guinea with description of a new species (Phasmatodea, Phylliidae) ZooKeys 939: 5

Web links

- http://www.wandelne-blaetter-im-netz.de/ Information on keeping and care