Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov

Varlam Shalamov Tichonowitsch ( Russian Варлам Тихонович Шаламов ; born June 5 . Jul / 18th June 1907 greg. In Vologda ; † 17th January 1982 in Moscow ) was a Russian writer , opposition and dissident in the Soviet Union .

biography

Varlam Shalamov was born in Vologda , a city around 500 kilometers northeast of Moscow . His father, Tikhon Shalamov, was an Orthodox priest and had lived as a missionary in the United States for twelve years , and his mother, Nadezhda Shalamova, was a teacher. He was the youngest of five siblings, his name is a simplification of the name of a saint of the Orthodox Church, Saint Warlaam of Chutyn (Warlaam Chutynski).

Varlam Shalamov finished school in 1923 and traveled to Moscow a year later, where he worked as a tanner in a leather goods factory. In 1926 he began studying at the Law Faculty of Moscow's Lomonosov University . In the following years he increasingly sympathized with the Soviet left opposition . In 1927 he took part in the demonstration marking the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution , in which criticism was made of the political development in the Soviet Union, which at that time was already strongly influenced by Joseph Stalin . Shalamov carried a banner reading "Down with Stalin" at the demonstration. A little later on the XV. CPSU party congress (B) on December 2, 1927, all leading opposition members excluded from the ruling party (→ Leon Trotsky , → Grigory Evsejewitsch Zinoviev ). The power struggle in the Soviet Union was already decided in favor of Stalin. Shalamov remained a supporter of the opposition and continued to participate - now in increasingly conspiratorial form - in actions that were directed against Stalin's increase in power. He saw himself as the heir to the Russian revolutionary movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Unlike his predecessors, however, he had to pay a much higher price for his political opinion.

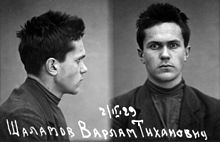

On February 19, 1929, Shalamov was in an illegal university printer for the distribution of Lenin's will , a letter from Lenin dated December 1922 to the XII. KPR (B) party conference , arrested. His law degree was thus obsolete. Until March 1929 he was imprisoned in Moscow's notorious Butyrka prison. Subsequently, he was sentenced as a “dangerous element” to three years imprisonment in the GULag prison system and to five years exile in the north of the Soviet Union. From 1929 to 1931 he was a prisoner in the Wischera department of the GULag ( Krasnovishersk camp point ), which was known at that time as the “ Solowezker special camp”, and performed forced labor there in a wood factory . In October 1931 he was released early from the camp and found work building a chemical combine in Berezniki .

In 1932 Shalamov returned to Moscow. His father died in 1933 and his mother died a year later. Shalamov married Galina Guds, a sister of the OGPU officer Boris Guds , in 1934 . A year later, their daughter Galina was born. In the years from 1934 to 1937 Shalamov worked as a journalist in Moscow and published essays and a short story in addition to his articles .

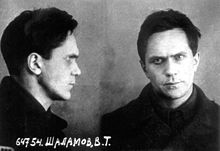

In January 1937 Shalamov was arrested again in the course of the Great Terror and again sentenced to camp imprisonment under Article 58 of the RSFSR Criminal Code , this time for " counterrevolutionary Trotskyist activity". His first wife immediately divorced him. He was sentenced to five years of forced labor in the "corrective labor camp" without a trial . In August Shalamov reached Magadan by ship on the Nagayevo Bay of the Sea of Okhotsk in northeast Siberia , in the Kolyma region. He had to do forced labor in the "Partisan" gold mine. In December 1938 he was arrested in connection with a "legal conspiracy" constructed by the camp administration and taken to Magadan prison.

Until August 1940, Schalamow worked in a camp on the "Black Lake" as a kettle, as an assistant to a topographer and as an assistant in earthworks. In August 1940 he was transferred to the Arkagala camp and worked there in a coal mine. Although his imprisonment ended in 1942, his internment was extended without further explanation until the end of the Second World War . From December 1942 to May 1943 Shalamov was in the penalty mine Dschelgala laid. In May 1943 he was sentenced again to ten years in a correctional labor camp in Jagodnoye (Magadan Oblast) for “counter-revolutionary activity”. The reason for his arrest was because he had described the author Ivan Bunin , who emigrated to France in 1920 , as a classic Russian writer. Shalamov fell ill and in the autumn of 1943 was sent to the "Belitschja" sick camp. From December 1943 to the summer of 1944, however, he had to work again in the “Spokojnyj” (German: the quiet ) mine . In the summer of 1944 he was denounced again and arrested again. In the spring of 1945 he came to the forest camp outpost of the Jagodnoye camp point. He fell ill again and was admitted to "Belitschja" again. In the fall of 1945 Schalamow worked in a branch of the lumberjacks, the "Diamond Spring". An attempt to escape failed, he was charged and transferred to the penal mine again.

Shalamov's odyssey through the camps of the Stalinist Soviet Union continued: between 1945 and 1951 he worked in Jelgala, in Sussuman and on the Duskanya River . He began to attend courses for medical assistants and got a light job in the surgical department of the Central Camp Hospital in the " Uferlager ". Shalamov began to secretly write poems that were written in Kolyma books .

From 1950 to 1953 Shalamov was a medical assistant in the reception of the Central Camp Hospital. On October 13, 1951, he was released from the camp, but as a freedman he remained a medical assistant at the camp point in Kjubjuma until August 1953. On September 30, 1953, he finished his work for the state mining and road construction company Dalstroi of the MWD , to which the penal camps of the Magadan area were subordinate. He had received permission from the Soviet State Security (from 1945 to 1954 NKGB ) to resettle in the European part of the Soviet Union. After his return he was confronted with the dissolution of his family; his now grown daughter refused to recognize him as a father, as former Gulag prisoners were also considered criminals.

From November 1953 to October 1956 Shalamov lived in the Kalinin area (now Tver) in central Russia. In 1954 he secretly began to work on the stories from Kolyma , which he wrote until the early 1970s. After Stalin's death in 1953 and Nikita Khrushchev's official distancing from Stalinism, Shalamov was rehabilitated on June 18, 1956 in relation to the 1937 charges against him. In the same year he married the writer Olga Nekljudowa (1909–1989) and moved back to Moscow. In 1957 Shalamov's first poems appeared in Soviet literary magazines, and from 1961 to 1971 four more times. In 1958, the 51-year-old fell ill and was disabled. In 1966 he divorced his second wife.

From 1968 to 1971 Shalamov worked on his childhood memories The fourth Vologda and 1970 to 1971 on Wischera. An anti-novel . After completing the stories from Kolyma , he smuggled the manuscript from the Soviet Union to the Federal Republic of Germany . There and in France they appeared in German and French as early as 1971. A selection of his stories from Kolyma in Russian in Tamizdat in London followed in 1978. After this publication became known to the Soviet State Security (from 1954 KGB ), Shalamov was forced to sign a declaration in which he announced that the people in the Kolyma Stories treated topic since the XX. CPSU party congress (February 14-25, 1956) is no longer relevant. Shalamov had become one of the Soviet dissidents known in the West alongside Solzhenitsyn .

From 1979 Shalamov lived in an old people's home. In 1980 he received the freedom bonus from the French PEN Club. Shalamov died on January 17, 1982 in a mental hospital ; In some cases this was seen as the last attempt to discredit Shalamov. After the fall of the Soviet Union, he was also posthumously rehabilitated in relation to the 1929 indictment in 2000. His grave is in the Old Kunzewoer Cemetery in Moscow.

reception

The Kolyma region, in which Shalamov spent a total of seventeen years of his life, is uninhabitable by Central European standards; in winter there are temperatures of up to 60 degrees below zero. Because it was hardly possible to escape under these conditions, the camp architects did not use barbed wire . The death from work was considered acceptable.

Warlam Tichonowitsch Schalamow is mentioned today together with Imre Kertész , Primo Levi and Jorge Semprún . In his laconic tales from the Gulag, as a “chronicler of the crimes of humanity”, he testifies to the Soviet variant of the European terror system of the 20th century. In doing so, the author closes a historical and literary gap that remained open until the end of the Soviet Union. In contrast to the Western European authors, who were increasingly gaining recognition and prestige, Shalamov's writing was a risk until his death in 1982.

The stories from Kolyma , which are considered to be Shalamov's main work, are among the most important texts on the Gulag, along with the works of Alexander Solzhenitsyn. In contrast to Solzhenitsyn, Shalamov tried after his rehabilitation to come to terms with the Soviet system, and he resisted the instrumentalization of his person for an anti-Soviet protest movement. When Shalamov returned from the camp, “the standards were shifted”. He had learned that under certain conditions man can transform into an animal in a very short time, and recognized "the extraordinary fragility of human culture and civilization ".

In 1991 the asteroid (3408) Shalamov, discovered on August 18, 1977, was named after him.

The first edition of Shalamov's work outside of Russia has been published by Matthes & Seitz Berlin since 2007 . On the 100th birthday of Warlam Shalamov, the issue of the Eastern Europe magazine was published in June 2007 under the title Das Lagerwriting. Varlam Šalamov and the processing of the gulag.

A theater adaptation of the stories from Kolyma came on stage in 2018 at the Cuvilliés Theater in Munich as Am Kältepol - Tales from the Gulag , directed by Timofei Alexandrowitsch Kuljabin .

Works

- Три смерти доктора Аустинo. (Short story The Three Deaths of Doctor Austino ), Journal October (1936).

- Собрание сочинений в четырех томах. Complete work edition, 4 volumes. Vagrius and Khudozhestvennaya Literatura, St. Petersburg 1998, ISBN 5-280-03163-1 , ISBN 5-280-03162-3 .

- Воспоминания. Memoirs. АСТ и др. Moscow 2001, ISBN 5-17-004492-5 .

- Works in German translation

- Article 58. Records of prisoner Shalanov. Translator Gisela Drohla . Middelhauve, Cologne 1967 DNB 458003824

- Kolyma: island in the archipelago. Translator Gisela Drohla. Langen Müller, Munich 1967 ISBN 3-7844-1584-9

- Shock therapy. Kolyma stories. Translated by Thomas Reschke . Verlag Volk und Welt, Berlin 1990 ISBN 3-353-00749-0

- About prose. Afterword by Jörg Drews . Translated by Gabriele Leupold , Ed. Franziska Thun-Hohenstein. Matthes & Seitz , Berlin 2009 ISBN 978-3-88221-642-4

- Hell's anchorage. Stories, poems, letters, photos. Edited by Nadja Hess, Siegfried Heinrichs. Stories, selected and transferred by Barbara Heitkam. Poems, letters and essays transcribed by Kay Borowsky . With an essay by Yevgeny Shklovsky. Oberbaum, Berlin 1996 ISBN 3-926409-80-0

- Work edition. Übers. Gabriele Leupold. Ed., Epilogue, glossary and note Franziska Thun-Hohenstein. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2009ff.

- Through the snow. Stories from Kolyma. 2013 ISBN 978-3-88221-600-4

- Left bank. Stories from Kolyma . 2009 ISBN 978-3-88221-601-1

- Artist of the shovel. Stories from Kolyma . 2013 ISBN 978-3-88221-602-8

- The raising of the larch. Stories from Kolyma . 2013 ISBN 978-3-88221-502-1

- The fourth Vologda and memories. 2013 ISBN 978-3-88221-053-8

- Wischera. Anti-novel. 2016 ISBN 978-3-95757-256-1

- About the Kolyma. Memories. 2018 ISBN 978-3-95757-540-1

literature

- Willi Beitz : Warlam Schalamow - the narrator from the hell of Kolyma. Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig 2012 ISBN 978-3-86583-732-5

- Dirk Naguschewski, Matthias Schwartz (ed.): Schalamow. Readings. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2018 ISBN 978-3-95757-554-8

- Manfred Sapper , Volker Weichsel (ed.): The camp write. Varlam Šalamov and the processing of the gulag. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin 2007 ISBN 978-3-8305-1219-6

- Warlam Schalamow, Wilfried F. Schoeller: Life or writing - The narrator Warlam Schalamow. Book accompanying the exhibition, with contributions by Wladislaw Hedeler , Wjatscheslaw Iwanow, Valeri Jessipow, Gabriele Leupold and Franziska Thun-Hohenstein. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2013 ISBN 978-3-88221-091-0

- Irina Pawlowna Sirotinskaja (ed.): K stoletiju so dnja roždenija Varlama Šalamova. Materialy meždunarodnoj konferencii. Antikva, Moscow 2007 ISBN 5-87579-104-7

- Franziska Thun-Hohenstein: Surviving in the Gulag. Varlam Šalamov's stories from the Kolyma. In: Trajekte, Zeitschrift, Zentrum für Literatur- und Kulturforschung , 9th year, # 18, April 2009, pp. 34–36

Exhibitions

- Life or writing. The narrator Varlam Shalamov. Literaturhaus Berlin 2013

Web links

- Literature by and about Warlam Tichonowitsch Schalamow in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Warlam Tichonowitsch Schalamow in the German Digital Library

- Website about the life and work of Varlam Shalamov (initiated by Irina Pawlowna Sirotinskaja, Russian / English)

- Ulrich Schmid: Non-literature without morals. Why Varlam Šalamov Was Not Read , Eastern Europe , 2007

- Illustrated biography of Varlam Shalamov , culture in Vologda Oblast (Russian / English)

- 30min Schalamow's story Lida Text reading by Felix von Manteuffel , in the audio archive of DRS 2

- Biography on the portal of Memorial Germany

Individual evidence

- ↑ Irina P. Sirotinskaja (ed.): K stoletiju so dnja roždenija Varlama Šalamova. Materialy meždunarodnoj konferencii. Antikva Moscow, 2007, ISBN 5-87579-104-7 .

- ↑ a b In Stalin's forge . In: NZZ, July 16, 2016.

- ↑ The head of the Soviet State Security (1934 to 1945 NKVD ) Nikolai Jeschow was relieved of his post in early December 1938 and replaced by Lavrenti Beria . The latter began to “cleanse” the authority of employees whom he believed to be supporters of Jeschow. Therefore, the time of the “legal conspiracy” correlates very strongly with this change, because the Magadan camp administration wanted to convince their new boss of their loyalty to the line.

- ^ Foreword to the English edition of the Kolyma stories. Penguin Books, 1994, ISBN 0-14-018695-6 .

- ↑ Yuri Belov and Christiane Freese (Editor): The psychiatry as a political weapon: documentary about the abuse of psychiatry for political purposes in the USSR . (Brochure, 1986.)

- ↑ Rainer Traub: FICTION: On pole of cruelty . In: Spiegel Special from 2007-09-25 . No. 5 , 2007.

- ↑ Sabine Berking: The battle has been waged for centuries. In: FAZ.net . November 29, 2013, accessed October 13, 2018 .

- ↑ Minor Planet Circ. 18137

- ↑ Special Issue Writing the Camp. Varlam Shalamov and ... Dt. Society for Eastern European Studies, July 5, 2007. Online

- ↑ Egbert Tholl: Terribly beautiful. In: www.sueddeutsche.de. March 2, 2018, accessed March 4, 2018 .

- ↑ Shalanov is an alias for Shalamov.

- ↑ p. 20: Lecture and work offer of the Junge Weltlesebühne, Berlin, with Gabriele Leupold, for school classes from 11th grade and libraries, 2019

- ↑ Jörg Plath: Witness in the death zone. The Literaturhaus Berlin is showing an impressive exhibition on the Gulag author Warlam Schalamow . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . No. 250 , October 28, 2013, p. 36 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Shalamov, Varlam Tikhonovich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Shalamov, Varlam Tikhonovich (English transcription); Šalamov, Varlam Tichonovič (scientific transliteration) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian writer and dissident |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 18, 1907 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vologda |

| DATE OF DEATH | 17th January 1982 |

| Place of death | Moscow |