Brava

| Brava | ||

|---|---|---|

| Satellite image | ||

| Waters | Atlantic Ocean | |

| Archipelago | Ilhas de Sotavento | |

| Geographical location | 14 ° 51 ′ N , 24 ° 42 ′ W | |

|

|

||

| length | 11 km | |

| width | 9 km | |

| surface | 67 km² | |

| Highest elevation |

Fontainhas 976 m |

|

| Residents | 6300 94 inhabitants / km² |

|

| main place | Vila Nova Sintra | |

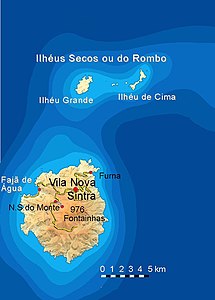

| Map of the island | ||

Brava (also Ilha Brava , dt., 'Indomitable island') is the smallest of the inhabited Cape Verde islands in the Atlantic . Located on the southwestern edge of the archipelago, it shares the vegetation that is favorable for agriculture with the neighboring island of Fogo, which is also volcanically formed and geologically located on the same base. Difficult to reach due to the steep rocky coastline, the island was settled late - mainly from the end of the 17th century - and has developed its own variety of the Cape Verdean Creole . Up until the 20th century, Brava was a base for transatlantic whaling , which led to constant emigration, especially to New England , which continues to shape the island socially and financially through cash payments from and networks in the diaspora. The mornas , poems and songs of farewell and mourning, fed from this experience, laid the foundation of Cape Verdean literature and music through Eugénio Tavares, who was born on Brava . To this day, tourism plays a minor role on the remote island.

geography

Brava is almost circular with a diameter of up to 11 kilometers and an area of 67 square kilometers. The middle mountainous island is the westernmost of the Ilhas de Sotavento (dt., Islands under the wind ') and lies west of the island of Fogo . Brava's altitude is barely enough to receive precipitation from the trade winds . However, since it lies in the lee of the volcanic cone of Fogo , the island is often covered by leeward clouds, so that evaporation is less and the vegetation is somewhat richer. The Cape Verdean writer João Rodrigues characterized Brava as "bathed in green and filled with flowers" and in this Madeira comparable to many barren islands of the archipelago. The conditions for agriculture, together with those of Fogo, are therefore better than on the other islands of Sotavento.

The island rises with steep cliffs to form a broad plateau, which is deeply cut by erosion valleys.

The island is more densely populated in the higher elevations. The island's capital, Vila Nova Sintra, and the pilgrimage site of Nossa Senhora do Monte can also be found here . On the east coast, the island's only permanent port is in Furna . In Vinagre there is an acetic acid mineral spring that was previously used for spa treatments.

About six kilometers north of the island are the uninhabited Ilhéus do Rombo , 20 kilometers southwest the submarine Cadamosto Seamount closes off the archipelago to the west.

geology

Originally a deep sea mountain of volcanic origin, the island has been lifted above sea level over time. Today, unlike Fogo, there is no more volcanic activity worth mentioning on the island, but much more seismic activity than on Fogo. The geological development of Brava can be divided into three volcanic stratigraphic units (from young to old):

- Upper unit

- Medium unit

- Lower unit

The lower unit consists of a submarine, volcanic succession of the Pliocene ( Piacenzian to Gelasian ) formed 3 to 2 million years ago . During this time Brava was in the seamount stage ; this part consists of hyaloclastites and pillow lavas , which are traversed by innumerable cogenetic groups of gangue . Geochemically, these are ankaramites and nephelinites . The lower unit was intruded in the Old Pleistocene (1.8 to 1.3 million years BP) by a plutonic alkali rock / carbonatite complex of the middle unit , consisting of pyroxenites , ijolites , nepheline syenites and carbonatites ( Sövites ). Between 1.3 and 0.25 million years BP, these two units were exposed to severe erosion; an erosion discordance formed with the subsequent upper unit . In the upper Middle Pleistocene 250,000 years ago, after a long pause, volcanism set in again, which predominantly produced phonolithic rocks. It is characterized by explosive, phreatomagmatic and magmatic ejecta. Pyroclastic flows (block and ash flows), pyroclastic ceilings with surge phenomena and countless craters formed by phreatic eruptions formed. Lava flows and lava domes were formed effusively.

A specialty of Brava is the occurrence of intrusive and extrusive carbonatites. The carbonatites are intrusive in the plutonic mean unit; they are of a younger age than comparable occurrences on the neighboring islands of Fogo , Santiago and Maio . Extraordinary, Young Pleistocene to Holocene carbonatites can be found in the Upper Unit and are unique for Cape Verde.

It can be assumed that the island has lifted itself out of the sea since the seamount stage, because there are submarine hyaloclastites and pillow lavas as well as raised beaches up to 400 meters above sea level. Estimates show an uplift rate of 0.2 to 0.4 millimeters / year.

Brava is traversed by many faults , lateral shifts and volcanic / tectonic lineaments , which have significantly shaped the development of the island. The intrusive tunnels of the lower unit are organized orthogonally with a predominant east-west orientation. Disturbances in the two upper units mainly follow the north-north-west to north-west direction.

The spatial arrangement of the disturbances corresponds more or less to the area of tension encountered on the neighboring island of Fogo. Both islands as well as the Cadamosto-Seamount and the Ilhéus do Rombo sit on the same substructure, which sits at a depth of around 4000 meters between 500 and 1000 meters thick marine sediments . The sediments in turn overlay oceanic crust from the Lower Cretaceous , which begins at a depth of around 5300 meters and extends to a depth of 13 kilometers.

history

Whether Brava was entered and settled by Africans before it was discovered by Europeans is unknown, but is considered unlikely. Brava was first entered by the Portuguese in 1462, and the first settlers settled permanently in 1573. At this time the peak of the slave trade in Ribeira Grande (on the Cape Verde island of Santiago ) had already passed, so that the small farmers from Madeira and Minho (northern Portugal) who settled on Brava no longer took part. In 1578, the English navigator Francis Drake landed on Brava to make a last stop before crossing the Atlantic on his circumnavigation after he had not been able to land on the other Cape Verde islands. His nephew Francis Fletcher, who was on board, described "an extremely sweet and pleasant island", which is called "brave" ('brave') because it keeps fruits of all kinds ready at all times, but offers no anchorage for ships. The only resident Drake found was a hermit, which is why he (incorrectly) considered the island to be otherwise uninhabited.

In 1680, the inhabitants of the neighboring island of Fogo fled the lava flows of the erupting volcano to Brava and ensured that the island was colonized for the first time, to which the large landowning families Fogo exported their system of plantations. These families - partly controlled from Fogo by means of feitores - kept the economy of Brava in their hands until the middle of the 18th century. Nevertheless, the large-scale farming of a white elite did not prevail on Brava in the long term, but the population was relatively mixed and mainly consisted of small farmers, shepherds, fishermen and craftsmen. In 1847 the archipelago's first public elementary school was established on Brava, but the colonial administration continued to leave education largely to the local private initiative.

The pirates , who frequently anchored in the bays of Brava in the 17th and 18th centuries (including Emanuel Wynne , who is said to have been the first to hoist the Jolly Roger ), were replaced by whaling ships from Europe and the USA in the early 19th century. who stopped in Brava and supplied themselves with water and food. The US whale schooners, who were still sailing under sail, hired young men from Brava as harpooners and thus spearheaded an emigration to the American east coast that lasted almost two centuries, especially to the old whaling ports of Boston , Providence and New Bedford . The first US emigrant to Cape Verde was a José da Silva, who was born in Brava in 1794 and became an American citizen in 1824. The Cape Verdean immigrants in New England were also called "Bravas" at the beginning of the 20th century; to this day, most of the members of the Cape Verdean diaspora in the United States come from Brava and Fogo, while the emigrants from the other islands have tended to go to other destination countries. An 1876 report by the Portuguese administration mentions a hundred people leaving Brava for the United States each year.

Men in particular emigrated, while women usually stayed behind or followed them years later. The Africanist Basil Davidson noted that the emigrants from Brava in particular, because of their lighter skin color, tried to be regarded as Portuguese in the USA and thus to circumvent the open racism directed against African Americans . Davidson sees the rejection that many of them experienced as one possible reason why the emigrants remained closely connected to their homeland in the long term. According to the anthropologist Luís Batalha, racism had a long tradition, especially in Brava and Fogo, where plantations and large farms made for a three-fold stratified society between “whites”, “blacks” and “mulattos”, while many others, early and until the 1930s Islands of the archipelago were later settled and developed a more flexible social structure. In the early 20th century, many daughters of Brava's upper-class families preferred to remain unmarried rather than marrying an overly dark-skinned partner; Deirde Meintel has identified a widely recognized norm of homogamy that only changed in the course of migration history: emigration provided opportunities for advancement and thus social mobility for dark-skinned people up to the elite, which softened the differentiation according to external characteristics; There was an increasing number of arranged marriages between emigrants and those at home who had never seen each other and in which skin color therefore played a lesser role. The sharp division between whites and blacks remained the norm in Brava until the middle of the 20th century.

From the early 1920s onwards, tightened state restrictions resulted in a sharp decline in the hitherto active migration traffic; the island was now isolated again and largely lost contact with the emigrants on the other side of the Atlantic, which the Brava expert Deirdre Meintel described as part of " deglobalization " ( Ulf Hannerz ). Especially since Cape Verde became independent from Portugal in 1975, Brava has gradually broken away from this isolation.

society

Because the island has been shaped by ethnic Portuguese and hardly by African immigrants, it (like the island of Boa Vista ) is sometimes referred to as the “white island” of the archipelago. Brava is particularly influenced by the transnational, especially transatlantic, connections to the emigrants. Thousands of emigrants return to the island every year for the “Cola San Jon” festival on St. John's Day. Since the 19th century, such festivals have served to showcase the high social status of the (often temporarily) returning migrants. The local society is visibly stratified according to how strong contacts there are with those who have temporarily returned home and who contribute a large part of the household's income. Since the tightening of the American right of residence after 9/11 and especially since the uncertainty caused by the financial crisis from 2007 , the trend towards permanent return of migrants has increased.

administration

The island belongs to the southern group of the Cape Verde Islands, the Ilhas de Sotavento . The capital of Bravas is Vila Nova Sintra . The second largest city is the pilgrimage site of Nossa Senhora do Monte .

Administratively, Brava is divided into a district of the same name ( concelho ) with two communities ( freguesia ).

| Concelho (circle) | Freguesia (Municipality) |

|---|---|

| Brava | São João Baptista |

| Nossa Senhora do Monte |

traffic

The northeastern fishing village Furna is a small ferry and trading port and the only place that offers regular access to the island. The western bay at Fajã de Água also serves as a port for parts of the year. In a multi-year food-for-work program , Germany financed an airfield on a headland near Fajã de Água, which opened in 1992 but has since been abandoned because of the consistently strong winds. Since the ferry connections to Furna have only been more regular since 2004 and there is no longer any flight connection, Brava has hardly opened up to tourism. In 2011 the fast ferry Kriola started the regular almost daily connection from Praia via Fogo to Brava and thus improved the connection to the island considerably, but in the following years there were repeated changes to the plan and unreliability.

The road network on Brava has been significantly improved in recent years - all villages on the island can now be reached via paved roads and with the Aluguer buses that are typical of Cape Verde .

Economy and tourism

After the island had lived mainly from whaling for a long time , the only notable branches of production today are some irrigation farming with the cultivation of corn, beans, bananas and papayas as well as cattle breeding (cows and goats) and fishing. There is a small cheese dairy in Cachaço. Trade, commerce and private households mainly live from the money sent by the emigrants.

Since the island is not suitable for mass beach tourism and is difficult to reach, the development for tourists has taken place slowly. The rare guests appreciate the calm and seclusion of the island. Accommodations are located in Vila Nova Sintra, Fajã de Água and Cova Joana . On the west coast near Fajã de Água there are natural pools by the sea, which can be reached by stairs and ensure safe swimming in the sea. Otherwise there are hardly any safe swimming opportunities on Brava.

Culture and language

Brava became famous through the musician and poet Eugénio Tavares (1867–1930), who with his sad mornas, written in Cape Verdean Creole , created a new, self-confident Cape Verdean music, whose songs often dealt with emigration.

In addition to the official language Portuguese, a Creole language is spoken on the island , which is part of the Cape Verdean Creole , but has developed specific characteristics. This island-specific language of Bravas was researched by the anthropologist Deirdre Meintel in the 1970s and carried out the most comprehensive study of all Cape Verdean creole varieties. The fact that the island has retained such extensive linguistic independence is therefore due to the island's centuries of isolation and the early large influx of settlers from Fogo in the 17th century, among whom there were relatively few slaves, which is why the population has remained ethnically Portuguese than on the other islands of Sotavento. Therefore, the Brava Creole is "at least mesolectal within the framework of a hypothetical Cape Verdean [language] continuum". Meintel's research has also established that even the Creole on Brava has a diatopic variety , i.e. that different regions of the island speak differently. This is, perhaps, but after the linguist Angela Bartens diastratically to explain, that depended on the social class, since especially the language of the capital as acrolect differs from that of the rest of the island.

Sons and daughters of the island

- Adelina Domingues (1888–2002), at times the oldest person in the world

- Nilton Fernandes (born 1979), football player

gallery

literature

- Susanne Lipps, Oliver Breda: Travel Atlas Cape Verde Islands . Ed .: Dumont. Dumont, Ostfildern 2005, ISBN 3-7701-5968-3 , Insel Brava, p. 153-156 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Originally: "bathed in green and filled with flowers". Donald Burness: Interview with João Rodrigues. In: Luso-Brazilian Review. ISSN 0024-7413 , Vol. 33, 1996, No. 2, special issue: Luso-African Literatures , pp. 103-107, here pp. 103 f.

- ↑ a b c Heike Drotbohm: Creole configurations of the return between compulsion and refuge. The importance of home visits in Cape Verde. In: Journal of Ethnology . Vol. 136 (2011), Issue 2: Afroatlantische Allianzen / Afro-Atlantic Alliances , pp. 311-330, here p. 316.

- ↑ Bruno Faria, João FBD Fonseca: Investigating Volcanic Hazard in Cape Verde Islands through Geophysical Monitoring. Network Description and First Results. In: Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences Vol. 14, 2014, pp. 485-499, doi : 10.5194 / nhess-14-485-2014 ( PDF ), here p. 487.

- ↑ João FBD Fonseca et al: Multiparameter Monitoring of Fogo Island, Cape Verde, for Volcanic Risk Mitigation. In: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. Vol. 125, 2003, pp. 39–56, doi : 10.1016 / S0377-0273 (03) 00088-X ( PDF ( Memento from April 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive )), here p. 46.

- ↑ José Madeira et al .: Volcano-Statigraphic and Structural Evolution of Brava Island (Cape Verde) Based on 39 Ar / 40 Ar, U-Th and Field Constraints. In: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. ISSN 0377-0273 , Vol. 196, 2010, No. 3, pp. 219-235, doi : 10.1016 / j.jvolgeores.2010.07.010 .

- ↑ Luís Batalha: The Cape Verdean Diaspora in Portugal. Colonial Subjects in a Postcolonial World. Lexington Books, Oxford 2004, p. 18.

- ↑ "a most sweet and pleasant Iland, the trees thereof are alwayes greene and faire to looke on, the soil almost full set with trees, in respect whereof its named the Braue Iland, being a store house of many fruits and commodities, as figges alwayes ripe, cocos, plantons, orenges, limons, cotton, etc. From the bancks into the sea do run in many places the siluer streames of sweet and wholsome water…. But there is no conuenient place or roade for ships, neither any anchoring at all…. The onely inhabitant of this Iland is an Heremit, as we suppose, for we found no other houses but one ”. William Sandys Wright Vaux (Ed.): The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake. Being his next Voyage to that to Nombre de Dios. Hakluyt Society , London 1854, p. 26 .

- ↑ Luís Batalha: The Cape Verdean Diaspora in Portugal. Colonial Subjects in a Postcolonial World. Lexington Books, Oxford 2004, p. 59 and p. 42, endnote 21.

- ↑ Luís Batalha: The Cape Verdean Diaspora in Portugal. Colonial Subjects in a Postcolonial World. Lexington Books, Oxford 2004, p. 76.

- ↑ Luís Batalha: The Cape Verdean Diaspora in Portugal. Colonial Subjects in a Postcolonial World. Lexington Books, Oxford 2004, p. 36.

- ^ Deirdre Meintel: Cape Verdean Transnationalism, Old and New. In: Anthropologica. ISSN 0003-5459 , Vol. 44, 2002, pp. 25-42, here p. 30 .

- ↑ Luís Batalha: The Cape Verdean Diaspora in Portugal. Colonial Subjects in a Postcolonial World. Lexington Books, Oxford 2004, p. 39.

- ↑ Aminah Nailah Pilgrim: "Free Men Name Themselves": Cape Verdeans in Massachusetts Negotiate Race, 1900-1980. Dissertation, Rutgers State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, May 2008, pp. 38, 83 f. (PDF) . On p. 144 there is a black and white photo of men and women from Brava who are believed to have arrived on a ship in New Bedford around 1900.

- ^ Basil Davidson: The Fortunate Isles: A Study in African Transformation. Trenton, NJ 1989, ISBN 0-86543-121-3 , p. 41 .

- ↑ Luís Batalha: The Cape Verdean Diaspora in Portugal. Colonial Subjects in a Postcolonial World. Lexington Books, Oxford 2004, pp. 69 f. , 45, 59 and 63.

- ^ Peter Duignan, LH Gann: The United States and Africa. A history. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1984, ISBN 0-521-26202-X , p. 364 .

- ^ Deirdre Meintel: Cape Verdean Transnationalism, Old and New. In: Anthropologica. ISSN 0003-5459 , Vol. 44, 2002, pp. 25-42, here p. 34 .

- ^ Deirdre Meintel: Cape Verdean Transnationalism, Old and New. In: Anthropologica. ISSN 0003-5459 , Vol. 44, 2002, pp. 25-42, here pp. 36-40 .

- ↑ Angela Bartens: Notes on Componential Diffusion in the Genesis of the Kabuverdianu Cluster. In: John McWorther (Ed.): Language Change and Language Contact in Pidgins and Creoles (= Creole Language Library. Volume 21). Benjamin, Amsterdam et al. 2000, ISBN 1-556-19668-7 , pp. 35-61, here p. 38 .

- ↑ On the festivals in general Heike Drotbohm: Creole configurations of the return between compulsion and refuge. The importance of home visits in Cape Verde. In: Journal of Ethnology . Vol. 136 (2011), Issue 2: Afroatlantische Allianzen / Afro-Atlantic Alliances , pp. 311-330, here pp. 320 f.

- ↑ Heike Drotbohm: Creole configurations of the return between compulsion and refuge. The importance of home visits in Cape Verde. In: Journal of Ethnology . Vol. 136 (2011), Issue 2: Afroatlantische Allianzen / Afro-Atlantic Alliances , pp. 311-330, here p. 326.

- ↑ Gerhard Schellmann: Fast Ferry Kriola (Praia - Brava - Fogo) with great turbulence. In: Reiseträume.de , February 26, 2013; Cabo Verde Fast Ferry responde às preocupações sobre a ligação com a Brava. In: Brava.news , April 7, 2017.

- ↑ John A. Holm : Pidgins and Creoles. Vol. 2: Reference Survey. Chapter 6.2.1: Cape Verde Islands. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, ISBN 0-521-35089-1 , pp. 273 f. , with a text example of the Creole by Brava on p. 274. For further details, see the references at Language Cape Verdean Creole of Brava. In: Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Language Structures Online .

- ↑ Deirdre Meintel: The Creole Dialect of the Island of Brava. In: Marius Valkhoff (Ed.): Miscelânea luso-africana. Colectânea de estudos coligidos. Junta de Investigaçoes Cientificas do Ultramar, Lisbon 1975, pp. 205-256. The assessment comes from Angela Bartens: Notes on Componential Diffusion in the Genesis of the Kabuverdianu Cluster. In: John McWorther (Ed.): Language Change and Language Contact in Pidgins and Creoles (= Creole Language Library. Volume 21). Benjamin, Amsterdam et al. 2000, ISBN 1-556-19668-7 , pp. 35-61, here p. 45 .

- ↑ In the original: "at least mesolectal in terms of a hypothetical Kabuverdianu continuum". Angela Bartens: Notes on Componential Diffusion in the Genesis of the Kabuverdianu Cluster. In: John McWorther (Ed.): Language Change and Language Contact in Pidgins and Creoles (= Creole Language Library. Volume 21). Benjamin, Amsterdam et al. 2000, ISBN 1-556-19668-7 , pp. 35-61, here p. 37 .

- ↑ Angela Bartens: Notes on Componential Diffusion in the Genesis of the Kabuverdianu Cluster. In: John McWorther (Ed.): Language Change and Language Contact in Pidgins and Creoles (= Creole Language Library. Volume 21). Benjamin, Amsterdam et al. 2000, ISBN 1-556-19668-7 , pp. 35-61, here p. 42 .