St. Sava Cathedral

| Cathedral of Saint Sava Hram Svetog Save |

||

|---|---|---|

West view of the cathedral |

||

| Data | ||

| place | Belgrade | |

| builder | Bogdan Nestorović , Aleksandar Deroko , Branko Pešić | |

| Construction year | 1926 to 2018 | |

| height | 77.34 m | |

| Floor space | 4,500 m² | |

| Coordinates | 44 ° 47 '53 " N , 20 ° 28' 8" E | |

|

|

||

| particularities | ||

| Mosaics | ||

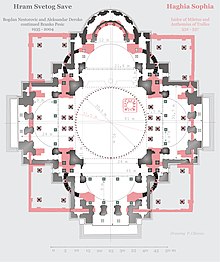

The Cathedral of St. Sava ( Serbian Храм светог Саве Hram svetog Save ; Serbian actually Sanctuary of St. Sava or Temple of St. Sava ) is a monumental Serbian Orthodox church in Belgrade in the neo-Byzantine style . With a built-up area of 4830 m², it is one of the largest Orthodox churches in the world. With an inner dome diameter of 30.5 m, the cathedral connects to the dome in the direct structural model of Hagia Sophia . The cathedral is designed as a classic central space with four conches and is dedicated to the first Serbian archbishop and national saint of Serbia, St. Sava (1175–1236). It was built on the Vračar plateau, a 134-meter-high hill in the south of Belgrade's city center, which is visible from afar, at the point where Sinan Pasha allegedly had the remains of Saint Sava burned in 1595. The church belongs to the Archparish of Belgrade and Karlovci of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Work on the church began in 1935 based on designs by architects Bogdan Nestorović and Aleksandar Deroko . However, only after the second competition in 1926 had an intense discourse that completely changed the building project of an originally nationally obligated church of the Serbian Orthodox Church, in particular also from the utopian idea of the all-Yugoslav pantheon in the planned mausoleum of Ivan Meštrović's Vidovdan temple . The final design was based on the universal early Christian symbol of Hagia Sophia on the main work of Byzantine architecture and, as a compromise between the multinational Christian identities in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, represented a different message. The last resistance manifested itself in January and February 1932 in statements of influential architects, artists and authors, and only fell when the Yugoslav king Alexander I intervened with interest. In its symbolic significance as a Serbian national building as well as its desired monumentality and search for an appropriate architectural style and form of expression, the building project reflected the intellectual, artistic and social movements in Yugoslavia during the individual phases of development, interrupted by historical upheavals. As the most discussed urban building project of the state, the location of which eludes a clear definition between sacral and secular, the symbolic function of the ' national monument ' is a central point of reception of modern national art and social history in addition to the architectural function . In her return to the imperial building of the Byzantine imperial church, it embodies not only an architectural, but also an ideological manifesto; it was intended as a supposedly new center of orthodoxy, which received a special response in the fall of Moscow and the capital of communism. The communist government of Yugoslavia initially advocated an aggressively anti-theist ideology; Only after the loosening of a related building ban could work on the project revised by Branko Pešić be resumed in 1985 . The liturgy held in the foundations of the Church on May 12, 1985 was attended by 100,000 people. As the communist elite of Yugoslavia withdrew from their atheist position, this represented a significant historical turning point. After the semicircular dome was spectacularly pushed from the floor into its intended position by a lift-slab system in 1989, work was halted during the years of civil war after 1991 over a decade. The exterior design of the church was completed in 2004. In the interior decoration, the twelve columns flanking the central room with elaborately designed combatant capitals in the so-called “Serbian-Byzantine style”, as well as the gold mosaics, are to be emphasized. The cost of decorating with scenes from the New Testament was borne by Russian President Vladimir Putin with an initial cost assumption from Gazprom Neft in 2016 within the dome. With an area of 1230 m², the dome mosaic completed by the Russian Academy of Arts under the direction of Nikolaj Muchin on December 13, 2017 represented the final phase of completing the church and the artistic design of the interior. For the 800th anniversary of autocephaly in 2019 of the Serbian Orthodox Church, a large part of the interior decoration should be completed, the Russian government will presumably take over the patronage for this too. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov attended the inauguration of the partial completion of the mosaics as part of a state act on February 22, 2018.

Location

The building site of the church was chosen in the line of sight of the most important commercial artery of Belgrade, the Ulica Kralja Milana , between Terazije and past the royal castle to Slavija in extension to Vračar Hill. The church was the end point and landmark of the avenue planned by Emilijan Josimović , which led from the former ski jump of Belgrade to the suburbs. With the architectural determination in the form of a Byzantine cross-domed church in close reference to the Hagia Sophia and certain national elements of the medieval “Serbian-Byzantine” building tradition, Belgrade was intended as the center of Orthodoxy in the chosen layout and in the monumentality of the church, which resulted in the loss of Moscow to compensate for the October Revolution as the center of Orthodox Christianity.

The church is located on the western foothills of the Vračar plateau at an altitude of 134 m about 500 m southeast of the Slavija. The elevation, 18 m above Terazije and Knez Mihajlova ulica and 10 m above Tašmajdan with the Church of St. Mark and Skupština, as well as 63 m above the Sava, made the cathedral on the striking relief point a landmark in the topography of the city. The plateau itself is named after the church - Svetosavski plato (Plateau of Saint Sava). To the south it drops steeply to the transversely running incision of the Mokroluški potok, which defines the guideline of the city motorway at a height of about 90 m.

From the gallery of the church, which runs around the dome at a height of 45 m, an elevator will in future invite visitors to a sweeping panoramic view. At 179 m above sea level, the view is at the same level as the line of sight of Topčidersko brdos (179 m), which towers south over the Mokroluški potok, which is due to the residential complexes of the Serbian government, the grave of the former Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito and the Museum of the History of Yugoslavia forms a symbolic ridge within the city. The gallery is not open to the public due to ongoing interior work (as of 2018).

After drilling the two 7.6 m diameter railway tubes of the New Belgrade Railway Junction to the southwest of the foundation walls of the church began on October 20, 1976, the planned installation depth of the crypt was changed. The Vračar tunnel runs past the church at a depth of 44 m. But the originally planned crypt, reaching over 20 m deep, could ultimately only be built 7 m deep. When the tunnel was being bored, there was also a longer interruption under the cathedral, as the tunnel boring machines at the south portal of the tunnel got stuck in leached clay marls or groundwater-shaped soil.

In addition to the cathedral, the Svetosavski Plato Park also houses the National Library of Serbia.

Building history

idea

The idea of building the memorial church goes back to the 300th anniversary of the burning of the bones of the first Serbian archbishop, teacher and Saint Sava of Serbia by Sinan Pasha in 1895. After the Berlin Congress and the complete independence of the Kingdom of Serbia from the Ottoman Empire, there was a growing desire within religious circles to erect a monument to the founder of Serbian autocephaly and one of the most important figures in Serbia's intellectual history. As a symbol of the medieval history of Serbia with its empire and its cultural prosperity, which was reflected in the many important Serbian Orthodox monasteries, the church in particular had a great interest in the construction of a building dedicated to its own founding father, which was quick and positive in intellectual circles has been recorded. Saint Sava was also worshiped by the people, which - reinforced by Russophile and Slavophile currents - found expression in the work of the Belgrade metropolitan Mihailo. Saint Sava was felt by the Serbian Orthodox Church as a symbol of the unity of the Serbs living in different countries and territories; his cult should promote a possible union of all Serbs. While in 1895 the Metropolitan set up a “Association for the Construction of the Memorial Church of St. Sava” with the participation of important Belgrade citizens, the idea of a memorial church on Vračar Hill in Belgrade began to develop. According to numerous hagiographic reports, it was on this very hill that the cremation of Sava's relic, ordered by Sinan Pasha , took place . Mythical traditions and wondrous tales in folk poetry raised the place of cremation to a sacred and spiritual place. The search for the original place of the stake has been carried out in Serbia since 1840, when the Savindan (January 27) was introduced as a general holiday in the principality. In addition, a priest had informed Metropolitan Mihailo in 1878 that a church on the Vračar had been destroyed by the Turks in 1757, where miraculous things were supposedly happening. Although the exact location could no longer be determined due to a lack of historical sources, Mihailo determined, mainly for practical reasons, that the hill was the most suitable place for a future memorial. Even the actual date of the event was not certain: the Serbian Academy set the date for the 300th anniversary as 1894, while Mihailo determined the celebrations for 1895 because the year had already passed. This coincided with the date generally handed down earlier. The date of the stealing of the relic from the burial place of Savas and the coronation church of the Nemanjids in the Mileševa monastery in 1594 by Sinan Pascha, the then Grand Vizier and important military leader in the Ottoman Empire, and its demonstrative cremation is April 27, 1594. Immediate trigger of the as The act intended to retaliate was the great Serbian uprising in the Banat between Timisoara and Pančevo. Of the Serbian Orthodox Church by the Patriarch Jovan (term of office from 1592 to 1614) strongly supported, he was part of a general had seized Serbian Uprising, who also Herzegovina and Montenegro and its military center during the Long Habsburg-Turkish war 1593-1607 in Banat lay. The relic of Sava in the Mileševa monastery was an essential element of identification for the Serbian national consciousness at the time. A description of the rich burial place of the monastery, according to which Sava's sarcophagus was "entirely decorated with silver ornaments and gilded figures", was given by the Venetian ambassador at the Sublime Gate Paolo Contarini during his stay in the Mileševa monastery in 1580.

Until then, the hill was commonly known as Englezovac - after the Scottish trader Mackenzie who owned most of it. At the suggestion of a group of citizens, the toponym should therefore also be renamed Savinac. In 1895 a small memorial church was built here.

The next step was the celebrations in 1904, when the centenary of the First Serbian Uprising was celebrated and a competition for the construction of the future large memorial church was announced.

Planning phase 1904–1932

First competition 1904

After King Aleksandar Obrenović declared the project to be a building project of national importance at the parliamentary session in Niš on January 25, 1900, it also acquired a political connotation. The first five plans and drawings were made soon after. In 1905 an architectural competition was announced in the Srbskim novinama . Since the commission assumed that the capacities would not be sufficient for a professional and substantive assessment of the competition entries within the Kingdom of Serbia, the sketches were sent to the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts in Russia for evaluation. However, none of the five submitted contributions was accepted by the academy because they did not meet the criteria of the call for applications. These specifications stipulated that the entries for the competition should be designed in the so-called "Serbian-Byzantine style" and that the building should have a floor area of 2000 to 2500 m² as well as a heating and ventilation system. Since none of the five competitors took this into account in full, none of the projects titled Enlightened , Alpha , Hagia Sophia , Drei Kreise and Omega were recommended.

Due to the political situation, which was soon given a military context by the Balkan Wars and the outbreak of the First World War, all further planning was suspended. In the interwar period, Belgrade grew by leaps and bounds as the new capital of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia; the population rose from 70,000 (1909) to 313,000 (1935), Belgrade was enlarged to include the left-hand Sava districts, prospered economically and gained additional political importance as the capital of a much larger multi-confessional and multi-ethnic country. These new framework conditions influenced the conditions for a new tender. However, they also made the construction of the church a delicate matter, as it was no longer only supposed to represent the Serbian nation, but also the new state as a whole.

Second competition in 1926

Tender

The project was given a new impetus by the establishment of a support association for the construction of the memorial church on the Vračar. The board was the Serbian Orthodox Patriarch Dimitrije . As a monumental building, the church should now have an area of 3000 m², be 80 m high and offer space for 6,000 people. Furthermore, the church was to be designed in the late Byzantine style and based on the buildings from the time of Prince Lazar (1329-1389), which are part of the so-called “Morava School” as triconchonal cross-domed churches. Particularly controversial was the restriction that only citizens of the kingdom or Russian refugees who lived within the country's borders were eligible to participate in the competition. However, Serbian and Russian architects were favored, especially since the latter were the main representatives of Neo-Byzantine historicism, as well as architects who already had experience in Neo-Byzantine art. The group of Serbian students who, through Theophil von Hansen, worked on the Neo-Byzantine current after graduation at the Vienna Art Academy at the end of the 19th century was successful . They were asked to give space to the elements of this tradition and to shape the competition in the further orientation with the national-romantic trend. The regulation stipulated that architects had to have experience in the Byzantine style, which restricted the selection mainly to Serbian architects. The church should also, as stated in the tender: “the largest and most monumental building in the country and the most important artistic achievement of our time” , be a “national monument and serve as a pantheon” .

With the preparation for hosting the Second Byzantine Congress in Belgrade in 1927, the prevailing trend of church architecture in Serbia that is committed to medieval Byzantine art was reinforced again. Thus the final decision of the church leaders was made that the church should be built in the style of historicism on the basis of classical Byzantine models and in the “Serbian-Byzantine style”. The bankruptcy was also a high point of neo-Byzantine architectural tendencies in Serbia. It is no coincidence that the submission deadline for entries to the competition - the call was published on November 3, 1926 in the Politika newspaper - coincides with April 30, 1917 with the holding of the Byzantinological Congress from December 10-14, 1927 in Belgrade. The discourse, behind which the result of the Serbian-Byzantine movement stood, did not arise primarily from the field of architecture, but first established itself through the review of historical Byzantine cultural influences and political discussions with the Eastern Roman Empire. From this perspective, which is predominant in Serbian historiography, he also penetrated areas of art, literature and popular culture. So the Russian scientists were not the only ones who expressed their passion for Byzantism. The fact that only Russian citizens residing in Yugoslavia were expressly admitted to the competition had its roots in Russian scholars' emigration. This was a constant in the 1920s, which made significant contributions to the architectural development of the Serbian capital. Russian architects were at the top of the hierarchy. So they took on the design of representative state buildings. Favored by the Yugoslav King Aleksander I, he preferred to hire her for the most important new buildings.

Gračanica as a source of inspiration

However, it is unclear why, of all things, two prototypes not specified in the tender, the Gračanica monastery church as representative of the national Serbian architecture of the Middle Ages and the Hagia Sophia as that of general Byzantine architecture, were the most widely used sources of inspiration. It is believed that the jury as well as the church leaders recommended these two models. The Katholikon Gračanicas was specifically considered the high point of Serbian medieval architecture and generally the best example of late Byzantine architecture of the Palaiological Renaissance, but the competition to build the Belgrade Cathedral forms the starting point of the architectural engagement with this well-known and important prototype of preserved five-domed churches in the late Byzantine art. Although Gračanica does not belong to the group of memorial churches and the dominions of Serbian monarchs, it was precisely this building that was chosen by architecture as a modern source of inspiration in the search for a national identity.

In October 1926, a total of 22 (24?) Architects took part in the second competition announced in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, including the country's leading architects in general. All work had to be submitted by May 1927. In addition to Bogdan Nestorović and Aleksandar Deroko, there were: Dragiša Brašovan , Milan Zloković , Milutin Borisavljević , the brothers Branko Krstić and Petar Krstić , Žarko Tatić, Aleksej Papkov , Miladin Prljević, Branče Marinković, and Žikander Pipersć. a. The evaluation was carried out by the commission composed of Patriarch Dimitrije , Jovan Cvijić as President of the SANU ( Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts ), the architects and academicians Andra Stevanović and Bogdan Popović and the architects Pera Popović and Momir Korunović . Among the 22 competition entries from national and international provenance, they found not a single one that met all the requirements. Not one of them was guided by the specification that the design of the church should be based on the “national” style of the late Byzantine “Morava school”. Most of the contributions were based on either the Gračanica monastery church or the Hagia Sophia. The Commission also complained that the overall level of the contributions was low.

Result

The highest-placed contribution came from Bogdan Nestorović , who took second place and presented a monumental copy of Gračanica. A few other projects were also bought up by the association. The real reason that some architects based themselves directly on the model of Hagia Sophia and its dome system was to be found in the size of the building. A first and third prize were not awarded. Bogdan Nesorović received 60,000 dinars with the second prize, Aleksandar Deroko's work was bought (15,000 dinars). Deroko himself graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Belgrade in February 1926 with a thesis on the Cathedral of Saint Sava. It served him at the end of 1926 as a template in the competition at the competition.

In Nestorović's elaboration, the award was given to a relatively uninspired model that, from the compilation of simple elements, was close to Gračanica's model, while other competition entries were partly more expressionistic. For example, the competition entry by the brothers Petar and Branko Krstić, who designed a monument in a romantic-expressionist style. Milan Zloković and Andrej Vasiljevič Papkov also planned a church with expressionist shapes. With Dušan Babićs elements of Expressionism and Art Deco were used. The other contributions were based more on conventional Neo-Byzantine designs, such as that of the Russian exile Vasilii Androsov, who paraphrased the dome of Hagia Sophia in a conventional design. Androsov's work was later implemented on a smaller scale in the church in Požega, which was consecrated to Emperor Constantine and Empress Helena.

In general, this did not meet the requirement of imitating a triconchal building type of the Morava School, but the submitted designs aroused great interest from both the professional and the public side. This formed the starting point for a general discussion about the identity of national architecture. No other discussion about a building had generated comparable interest in the country, of which, in addition to numerous publications, a booklet by the art critic Kosta Stranjić from 1926 and the articles written in Politika and Vreme in 1932 bear eloquent testimony. Numerous renowned architects, art critics and artists took part.

Public polemics between traditionalists and modernists

What then developed between 1927 and 1932 was the most important discussion on architecture in the history of Yugoslavia. With the enthronement of the new Patriarch Varnava, the project received a surprising impetus. In 1930 Varnava determined that Bogdan Nestorović (1901–1975) and Aleksandar Deroko (1894–1988) should use their submitted designs to develop a synthesis in the sense of neo-Byzantine tendencies based on the classic early Byzantine models of Constantinople. In 1931, the synthesized Nestorović-Deroko design of a significantly enlarged church, which has now been expanded to well over 3,500 m² and had a monumental dome approximately the size of Hagia Sophia, was accepted by Varnava and the commission for the construction of the church. This heated up the discussion between architects and other artists, which particularly focused on the top-ranked contribution by Nestorović.

Above all, the structure of the church that Nestorović presented in his first work in 1927 was incomprehensible to many; With thirteen pyramidal-stepped domes and decorative elements, which even laypeople immediately noticed as quotes from Gračanica's architecture, it fulfilled all the requirements of the competition, but the lack of innovations in the design was rightly pointed out. The sketch was soon published in the daily newspapers and quickly criticized. The greatest opponent not only of the best-placed design, but of the entire competition was the art scholar Kosta Strajnić. In 1926 he had sent the Serbian Orthodox Church a polemical text that nobody wanted to publish. He criticized the nationality of the allowed competition participants, who all had to come from the Kingdom of the SHS, but in particular also that the church was to be built in the “Serbian-Byzantine style”. Strajnić was particularly a supporter of the Yugoslav pantheon, which Ivan Meštrović had planned from 1905 as a mausoleum of the memory of the Blackbird Battle. From this opposition between the two propositions of the Vidovdanski hram (Yugoslav pantheon) and Svetosavski hram (Serbian pantheon) developed into the two-tier expert discussion in which the population also showed keen interest. In particular, following the merger of the two plaster models required by King Alexander I as plaster models by Deroko and Nestorović on a scale of 1: 100, which were made by the modeler of the Serbian National Museum Milan Duhač, it forced Nestorović to create his design with corrections from Deroko's work to provide. It was intended to completely change the appearance of the church, since it no longer approximated the silhouette of Gračanica, but that of Hagia Sophia.

Designation of the architects - Bogdan Nestorović and Aleksandar Deroko

Synthetic redesign in 1932

The sharp polemics surrounding the building, based on extremely contradicting ideas of architects, sculptors and the media in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, culminated in 1932. Leading artists and architects of the country took part in the discussions and appeared in the between January 18, 1932 and February 13, 1932 VREME magazine in the section: “What should the memorial church of St. Sava look like. From Gračanica to Hagia Sophia ”.

The starting point was the publication of the sketch of the definitive elaboration of the appearance of the church by Nestorović / Deroko on January 1, 1932 in Politika ("Rešeno je pitajnje skice za svetosavsku katedralu u Beogradu"), which is unknown to both the general public and art critics. In the presentation as in the accompanying text, the final completion of the church on the basis of Hagia Sophia was described, although the result was still a synthesis of the previous competing contributions by the two authors. The passion. with which the debate gained new momentum and lasted for over two months, far surpassed that of the call five years earlier. Nestorović described dimension and inspiration for the design in Politika. After the tender had only planned an area of 3000 m² and space for 6000 worshipers (it should be 60x60 m in size), he now described a building that was significantly enlarged to 91 × 81 m for 10,000-12,0000 worshipers and a semicircular equivalent to Hagia Sophia Dome.

The church had lost all clear reminiscences of Gračanica, the reason may be in the provisions of the buildings. While Gračanica was planned and built as a bishop's church, as a monastery of a monastic community for the needs of monasticism, the function of Hagia Sophia as a large urban church and imperial church of the Eastern Roman Empire met the needs of the planned Belgrade cathedral more closely. In addition, the break with the Orthodox tradition in Russia and the demolition of the Moscow Cathedral by Stalin in 1931 made the center of Orthodoxy vacant. In its "imperial" dimension of this kind, the church should be understood as a statement for a new center of Orthodoxy. The return to it was not just an architectural manifesto, it was an ideological one.

However, the discussion of the reference to the Gračanica building type, which was ultimately not realized here, meant that this subsequently became the most widely adopted model as the actual Serbian national monument in the church buildings that were further realized, here also in the Serbian diaspora. As a result of the conflict in the architectural style of St. Sava, an idea for the national style of an actual Serbian architecture had nonetheless emerged. The discussion about this question, which is the essence of the debate, could therefore only be realized in the following decades on other buildings. In the comment of the Krstić brothers, as the builders of the Markus Church in Belgrade, they realized the first religious building in Belgrade based on Gračanica, from January 22, 1932 a first clear plea can be found. They warned against a synthesis between such significant architectural achievements, which could be built either in the size and the effect of the interior of Hagia Sophia or according to the aesthetic specifications of Gračanica's rhythmic facade structure.

The sculptor Toma Rosandić, who pleaded for a monument, took part in the discussion , while Ivan Meštrović wanted the Yugoslav pantheon to be realized in the building . It is not known why Nestorović completely changed the design, but it was certainly also because of the interest of King Aleksandar I of Yugoslavia in the building, who vetoed Varnava's decision by decree after the Association of Yugoslav Engineers and Architects of the Belgrade Section (Udruženja jugoslovenskih inženjera i arhitekata - sekcija Beograd) in an open letter to the King, the Patriarch, the Association for the Promotion of the Church of St. Sava and the Ministry of Law, Construction and Culture after the decisions of the meeting on 11 February 1932 had spoken in favor of a repetition of the competition.

Thus, the project was now opposed to a strong public discourse with numerous negative evaluations in the project. In the situation, Varnava called some of the members of the committee of the commission as well as experts to a meeting with the king. The king was presented with plans and concepts from the sketches drawn up by Nestorović and Deroko, as well as drafts of the urban design of the city area, and the sizes and dimensions of the church were explained. After extensive discussions, Alexander I ordered a plaster study from both authors. Alexander I committed himself to an annual payment of 2,000,000 dinars, which would bear the annual cost of construction. Fundamental to the final form of the merged design was that it stylistically followed Byzantine early Christian models, but conveyed symbolically complex universal ideas that echo the spirit of the time and reflect the political ideologies during which the architectural design was created. Basically, however, it was not the dimension of the church - as the largest Orthodox church planned at the time, it was to assume the function of a kind of Orthodox Vatican - but the question of style. This made it possible to work from a dimension that was only comparable with Hagia Sophia, not from the fund of medieval Serbian art. The Church of St. Sava thus ultimately took on the size of the dome and the monumental shape of Hagia Sophia. The few analogies to Gračanica are only indicated in the elongated tambour and the arrangement of the five smaller domes around the central dome.

The official building permit was approved on July 4, 1932 by the building authorities in Belgrade.

The archetype of Hagia Sophia as a model

Nestorović's first draft was originally based very closely on the concept, the facade design and the silhouette of the Gračanica monastery church . In its further revision, this model was brought closer to the monumental classical Byzantine style of the 6th century in the age of Emperor Justinian I. Aleksander Deroko's own design, which was more closely based on the direct model of the main church of the Byzantine Empire , the Hagia Sophia in today's Istanbul , thus provided the actual starting point for the synthesis of both concepts. As a central dome , the final Nestorović-Deroko design differs from that of the Hagia Sophia in particular in terms of its floor plan, as no merging of the basilica and the central building was chosen, as well as the four semi-domes of the conches and the different structure of the galleries. The cathedral of St. Sava is also a tetraconchus . The fundamental square from which the geometry of Hagia Sophia can be derived is 99 Byzantine feet by 0.313 m, resulting in a diagonal of 140 Byzantine feet. The basic square of the Cathedral of Saint Sava is exactly 31 m as in Hagia Sophia. Nestorović's reference is based on the dimensions of the central square and the circle inscribed on it in the diameter of the dome, which is based directly on the construction of Hagia Sophia. The dome is comparable in diameter, but the types are different. Hagia Sophia has a dome, i. i. a flat dome whose base circle lies outside the base square. The dome of the St. Sava Cathedral is a semicircular hanging dome with a high drum. The dome of Hagia Sophia is outwardly without a drum, its 40 window openings emanate from the convex dome. Overall, the domes of the Western and Eastern churches differ; Roman and Byzantine art generally preferred half-domes as forms derived from the circle of circles, which were considered to be the most perfect, while the western church developed a pointed dome over the pointed arch of the Gothic, as in the cathedral in Florence, which usually also have an opaion for exposure, which is often from a lantern is covered. The latter come closer to the structurally ideal shape that results from the chain line . Domes of the western and eastern churches also have different spatial effects, which result from the typical proportions.

From the silhouette of Hagia Sophia, which has only one dome, the Cathedral of St. Sava with its 18 domes of different sizes differs more. In the paraphrase of the so-called " Serbian-Byzantine architectural style ", which since the completion of Gračanica preferred the five-domed memorial church type for the most important foundations, four 44 m high small domes are located around the main dome, which serve as bell towers. The entrances to the conches borrow from the Raška school in that the portals are tent-shaped. The marble cladding is also obliged to these, as in the primate monastery of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Studenica. However, these finer distinctions recede in the overall Byzantine impression. The new design has enough independence and individuality not to be understood as a mere copy of Hagia Sophia.

While the basis of the design is Byzantine, elements of the exterior and interior decoration are indebted to motifs of national architecture of the Middle Ages. Bas-reliefs and decorative cornices are reminiscent of portals and windows in Studenica , Dečani and Kalenić . Due to the monumentality of Sveti Sava, however, no actual model from national architecture was available for the composition of the overall design. The authors of the interior design have stratified the church into several zones: up to a height of 7.40 m it is covered by green and red marble and subtle ornamental decorations. From a height of 12 m, Deroko provided the lining with mosaic decoration.

The naos is framed by twelve 7.40 m high columns with warrior capitals and consoles. Eight double-window biforias with twisted marble columns set vertical accents. The southern and northern gallery end with a bezel standing on two tetrapylons. A rosette behind it is covered by more than 1/3. The choir can be found in the gallery in the west. Instead of the bezel, a cone with an uncovered rosette is formed here. The iconostasis is planned as a marble templon in front of the apse. Around the dome is a gallery with 24 twisted marble columns. All marble stone carvings are designed as a bas-relief and, in addition to floral ornamentation, often show animal figures or the double-headed eagle in the Serbian national coat of arms.

Execution phase

Construction 1935–1941

The actual construction work began on Vračar in 1935. The previous church on the square of the new one was demolished and a little church of St. Sava was built to replace it. After preliminary work to explore the terrain, the first actual construction work began in 1936/37. Foundations were laid for the foundation walls in 1935. For this purpose, 12 m long hollow steel piles were drilled into the earth, into which concrete was later poured. A total of 200 bored piles were laid in this way. In 1939 the brick walls were raised up to 12 m. Above that, the work on the half-domes and dome-yoke arches should have been carried out. The foundations of the church were consecrated and the founding deed was laid down on May 10, 1939. The inauguration ceremony was the largest ecclesiastical manifestation held in Belgrade up to that point. For this purpose, a large number of believers gathered in a procession across Ulica Kralja Milana to Vračar, where the then Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church Gavrilo V. Dožić held the ceremony inside the foundation walls at the construction site. The conclusion was a lecture by Guslaren Petar Perunović , who gave an epic about the construction of the Church of St. Sava to church and political dignitaries as well as several 10,000 Belgrade residents. The procession and speeches were broadcast directly on Radio Belgrade, so the ceremony could be followed everywhere in the country.

For the further construction 16 marble columns had to be procured, 4 each on three sides of the naos and another four in the vestibule in the west entrance. Only the east sides with the altar apses are without columns, but 6 decorative twisted columns were provided within the apse vault. Vertical construction was not possible without the introduction of the pillars, so a commission was appointed directly to the quarrying area of Carrara's marble quarries. The commission was headed by Nestorović, Deroko and two specialists from the stonemasonry industry in Serbia. White Carrara marble from 2000 m above sea level was procured for capitals for columns; the column trunks came from the Montecatini quarry (Seula) in Baveno on Lake Maggiore . A total of 16 trunks of green marble were brought from Montecatini as well as 6 red ones for the twisted decorative columns of the chancel. In Baveno, all 16 large columns with a height of 8 m and a diameter of 1 m were turned on lathes that were still operated by water mills. After their arrival in Belgrade, they were first statically tested. The capitals of the pillars arrived at the construction site in prefabricated blocks with the pillars on January 20, 1940. Capitals and consoles were processed to their basic shape without ornamentation. Josif Grassi, Professor of Applied Arts at the University of Belgrade, took on the final design. Based on Derokos 1: 1 drawings, he made 4 main variants for all 16 large capitals and also for the 6 small ones. Preparatory work was done in clay, which was cast in natural size plaster. The final marble capitals were created using the stonemason technique based on these models. As the war was noticeably closer in the spring of 1941, the columns were immediately encased in protective structures. They were first covered with straw and ropes, then pulled up around a brick wall and sand poured into the cavities. When it looked like the work was gaining momentum and with the 24 marble columns, 24 warrior capitals and 6 consoles that the stonemason company "Intramesion" had placed in the designated places, as well as a total of 6 consoles and 9 capitals based on drawings by Derokos by Grassi Once the Jablanica granite for the plinth was finished, the construction site was abandoned for several decades. All columns were preserved until 1985, but due to material damage, not all of them could be used in their original form.

Cessation and long-term interruption of work 1941–1984

During the Second World War

When the Third Reich launched a surprise attack on Belgrade and Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941, work on building the church was stopped with immediate effect for several decades. The German Wehrmacht occupied Belgrade on April 11, and the Serbian Patriarch Gavrilo was interned in the Dachau concentration camp. The Wehrmacht used the walled floor plan of the church as a depot for military equipment, as did the Red Army and Tito's partisans later. The organization of the construction site with the offices of the construction company "Rasina" with all materials for building the church were emptied. German soldiers broke into the rooms of the patriarchal seat and into the cabinets of Professors Nestorović, Deroko and Zažina in the technical faculty and destroyed all existing documents. The entire technical documentation, with the exception of the project idea, which Deroko had brought to a safe place in the basement, was lost as a result. All the assets of the organization for the construction of the Church of St. Sava were destroyed or stolen, and all funds for its construction disappeared.

Aleksandar Deroko buried the original blueprints wrapped in a protective cover and the detailed drawings of the ornamentation in dry sand in his cellar. Even so, moisture had seeped in, but it had only rotted the edges of the plans.

During the communist period

After the war there were no material or any other possibilities for resuming work. The new communist rulers, who are declaratively atheistic, quickly and openly opposed any concern of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the further development of the church. The construction site lay fallow and was used by children as a playground or by circus troops as a performance area.

Despite decades of efforts by the Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church German (Patriarch from 1958 to 1990) and 88 requests to the leadership of the Union of Communists of Serbia to get approval for further construction, the politically-induced construction freeze lasted until 1984. The development association was also established in 1948 dissolved for the construction of the church; the church took over its tasks through the committee for the management of the patriarchate. In 1953, the secretariat of the Ministry of the Interior confiscated the entire property of the Association for the Building of the Church, including the foundation walls of the church, by decree 2 / 3-11.855, and declared these as public property. However, this decree was never officially sent to the Church. Nevertheless, the church sued various addresses to have the nationalization lifted. In 1962 the Federal Commission for Faith Issues announced to the Church that public property could no longer be returned to the Church.

After German was appointed Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church in 1958, one of the main concerns of his tenure was to continue building the church. So every month he sent his titular bishop to the mayor of Belgrade with a list of concerns, including the demand for the removal of the garages within the walls of the church as well as all other objects not belonging to the sacred character of the complex. After this was achieved, he personally asked 88 times for the object to be returned to the church. German's persistence led him through all the structures of the Yugoslav administration, the patriarch spoke of the fact that they sent him from "Pontius to Pilate", from the lowest organs of the regional authorities to the offices of the city and the executive organs of the Serbian government and Yugoslavia .

When the Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church asked the President of the Executive Chamber of the Serbian Government Dragim Stamenković on April 28, 1966, in the presence of German, the church was offered to cover the foundation walls with a roof and to set up a church museum or a fresco gallery. After the synod saw no other possibility of conserving the object in any other way, it agreed to the proposal of a temporary solution in the form of a church museum, but not a fresco gallery, and was thus played out afterwards by the communist rulers. Even Petar Stambolić insisted on any further discussion of the problem that the church had entrusted the regulation of the future of the Church of St. Sava to the comrades of the Executive Chamber of SR Serbia. The church was also given a change in the content of the conversation, in which the location would become a “museum of ecclesiastical antiquities” and a “gallery for frescoes” as well as state supervision. The phrase “Museum of Church Antiquities” was an innovation that the church remained very suspicious of because of the obviously undefined property designation. The offer was therefore no longer supported, and the further demands for further construction were repeated even more relentlessly. The possibility of donations from emigrants for further construction was explored, which was immediately rejected. After the Serbian National Library was built in front of the porte of the foundation walls, even this was considered a reason for a relocation, which the then President of the Serbian Parliament Dragoslav Draža Marković had offered.

The situation changed after Dušan Čkrebić was elected President of the Serbian State Presidium . On June 19, 1984, he informed German and the members of the synod that the church could be built on the intended site. Čkrebić recommended, however, that this should not be made public and that construction work should only be resumed in silence so that no counter-reaction could develop. Even the functionaries in the higher positions of the Serbian government, who had previously been completely averse to the project, now tacitly tolerated the decision of their younger colleagues and remained in solidarity with the decision. The decision was not hidden and of course it was a sensation.

Construction work resumed from 1984–2016

Second consecration of the church

With the general approval of the continued work of the church by the Serbian socialist government in 1985, a new architect was appointed to complete the temple. To this end, Patriarch German appointed the architect Branko Pešić (1921-2006), a student of Bogdan Nestorović, in September 1984 in his residence in the Patriarch's Palace and informed him that he was selected as the architect for the construction of the church. Pešić, who had previously planned the Beograđanka skyscraper in the city center, had to modify parts of the church design, but mostly stuck to Nestorović's last final design. The static construction drawings lost during the war and all construction projects were missing.

Revision of the plans by Branko Pešić

In particular, Pešić changed the dimensions of the dome, whose outside diameter was increased from 32.63 m to 35 m. The dome was raised by 5 m and the dome cross grew from 6 to 12 m. As an adaptation to the aesthetic modernity, the facade was given a more uniform appearance by omitting some decorative details, the planned facade made of sandstone from Beolvode, from which numerous representative buildings of Belgrade were built, was made by Pešić with white marble and red granite for friezes, cornices, arcades and pilasters planned. Branko Pešić had also decided to carry out the construction in reinforced concrete.

The crypt with an area of 1,600–1,800 m², a chapel of the Holy Prince Lazar and the treasure house of St. Sava, which was planned by Nestorović ', was not included in the construction of the church in 1935. Pešić had them subsequently integrated into the planned building in the intended dimensions.

Aleksandar Deroko had buried some of the building plans in a war hiding place in the basement of his apartment and handed them over to the patriarchate after the war. However, since the heirs of Nestorović could no longer locate any plans for the statics in the architect's archive, Pešić asked Aleksandar Deroko as the only living person of the original architect for further help. Deroko, who was actually only the main author in the ornamentation of the facade, capitals and plinths and windows of the church, was able to show Pešić further plans at the meeting, but the static construction plans remained lost. Deroko Pešić secured Deroko - and explicitly only him - all necessary help in the further construction of Sv. Sava too.

Pešić's revision of the silhouette of the church was based on the basic plan of the Nestorović-Deroko design. In addition to increasing the height of the dome, he increased the dimensions of the half-domes, changed the facade design, designed a cross for each of the domes and enlarged the cross of the dome from 6 to 12 m with a weight of 4 tons. The arcades and pilasters of the windows were changed, the facade was planned in white marble instead of sandstone, bands of the arcades on the window arches were structured with red granite, windows, doors and rosettes were newly formed. The official extension was opened in a fair at which around 100,000 Belgrade residents in the still communist Yugoslavia on May 12, 1985, opened. The actual construction work began on April 14, 1986. The work required numerous structural interventions in particular, as the preparatory work found for the foundation walls of the four pillars for a dome of 35 m diameter was not sufficiently dimensioned and the supporting walls of the half-domes were made of statically insufficiently strong bricks had been. Reinforced concrete was inserted at all critical points of the foundation walls and, in particular, the originally intended single-shell dome was provided with a double shell construction with a 2 m high corridor between the shells.

Construction of the dome in 1989

The work on the dome made of prefabricated concrete elements, measuring 30.5 m inside and 35.15 m outside, was innovative and unique in this form for a structure with complex geometries. Based on a relatively unusual idea from the engineers Vojislav Marisavljević, Dušan Arbajter and Milutin Marjanović in the projection office “Dragiša Brašovan” of the “KMG-Trudbenik”, Pešić planned and executed them on the floor of the church from prefabricated assembly parts to lift them -Slab system to be raised to the intended height of 40 m. Otherwise, the 12 m high cross and the copper sheets of the dome would have had to be used at a height of 65 m, putting the fitters in danger. All work processes were carried out on the ground and with prefabricated materials. Before that, the foundations of the church were reinforced again, as they were only 6 m deep before the war, which did not guarantee the structural security of the structure. As a result, they now reached to a depth of 17 m, where they anchored in solid rock.

The greatest advantage of the structural innovations applied by "KMG-Trudbenik" was the speed with which the construction of the church was implemented from prefabricated heavy reinforced concrete support elements, and various other work could be carried out in parallel. From a structural point of view, the complex geometry of the building required the structure to be broken down into prefabricated elements that were as straight as possible. All the walls of the church were designed as hollow boxes, which gave the church a massive appearance after it was completely assembled. All curved surfaces - galleries and vaults - were cut into units of elements that were curved in two dimensions and only joined into a three-dimensional shape after they were installed. The dome and semi-dome were subdivided into linearized elements which, as a design, formed a system of curved beams with two curved shells. The prefabricated components were then fused into one unit in place in situ, which is supposed to guarantee strength and durability. All of these structural innovations helped make the building 30-40% lighter overall than would have been the case using the methods in the original construction plan.

As a preparatory work for the main task of lifting the dome, the four 400-ton pairs of the 24 m bridging zygomatic arches between the four support columns were assembled between January and June 1988. In doing so, they were pulled into the air on so-called "chains", where they remained hanging until the supporting vertical elements of the column were cast for them under them. Only then were they released from the "chains" so that the domed yokes and columns formed a portal-like structure. On the outer sides of the four yokes, the four half-domes with a width of 24 m and a double shell made of eight reinforced concrete grids were assembled from prefabricated assembly elements by inserting reinforced concrete slabs and in-situ assembly.

The construction of the dome began at the beginning of November 1988 and was completed at the end of February 1989. Since all concrete work was carried out in winter, the fresh concrete matured by means of electrical resistance heating of the steel girders ("electrical resistance thermal treating"). In construction and assembly, modern electronic procedures were used in project planning and calculation as well as in all phases of lifting. This was particularly important because the heavy assembly components had to be brought into precisely predetermined positions that did not allow subsequent corrections. The assembly of the heavy dome structure was carried out with the aid of numerical methods and specially developed programs, without checking any parameter tests on a model. As a basic element of the dome, the lower drum with a diameter of 35.15 m was cast as a cassette-shaped, monolithic concrete ring on the ground on a 1.20 m thick gravel slope. This carries the upper drum with 24 window openings as well as the hemispherical arching of the double-skinned dome 28 m high. On the concrete ring, in which a 100 m long corridor with stairs leads to the inner dome gallery as well as to the outer gallery around the dome, the upper drum with elements for 24 yokes for the dome windows, above that the 24 double semicircular arches of a special, light reinforced concrete grid was mounted. The reinforced concrete grid carries prefabricated reinforced concrete slabs on the upper and lower hemispherical spheres of the two shells. The reinforced concrete slabs of the upper shell were then covered with copper sheets, the interior of the spheres of the lower shell later with gold mosaics. A ring in the upper shell of the hemispherical sphere carries the 12 m high, 4 ton gold-plated cross, of which 10 m are externally visible. After the copper cover and the large gold-plated cross had been attached to the dome, which was on the ground between March and April 1989, the planning of the elevation entered the decisive phase.

In preparation, steel girders were assembled, hydraulic systems were built according to “Trudbeniks” specifications by “Prva Petoletka-Trstenik”, a company that was a leader in the construction of pneumatic and hydraulic systems in the SFR Yugoslavia, robotized reinforced concrete slab pushers were installed, and work scaffolding was installed Sensors attached to the sensitive components of the structure, which made it possible to continuously monitor any loads and deformations.

After the lift-slab system was brought into position under the dome, the dome, which weighs over 4,000 tons on the hydraulic scales and is 28 m high below the cross, with a 28-ton copper roof and 4-ton cross, was lifted by 16 hydraulic cylinders , which were interconnected in four groups, slowly lifted. The electro-hydraulic cylinders worked synchronously with an automated hydraulic manipulator, which inserted concrete slabs, each 11 cm thick, under the supports of the raised dome, so that there was no more than 5 mm horizon difference on either side. The weight and diameter of the dome as well as the required height required 20 working days on the lift slab system. The computer-controlled hydraulic system developed an integral lifting force of 5,000 mega-pounds, which was distributed synchronously to the four hydraulic cylinder groups. On average, the rate of uplift was 2 m per day, with no lifting for more than 5 hours at a time, so that the resulting air space could be prepared for the next step by concreting the column underneath in situ. Over 280 electronic elastomers were spread across the entire dome and its elements. The hydraulic components were corrected with the measurement data of the instruments, which enabled automated control from information about horizontal cylinders and differential pressure gauges and their evaluation in specially designed computer programs during the entire lifting action. A completely independent leveling system was connected to the computer switch controls, which allowed constant corrections from the leveling information during the lift. This system would have been automatically switched off immediately if a deviation of 5 mm had been exceeded. During the exact uplift, the computers continuously processed 24 essential data sets.

In the first phase, in order not to destroy the historical foundation walls from 1941 as well as the marble columns that were already installed at that time, an elevation of up to 13 m was carried out on temporary supports that led past the bell towers. The dome, which was pushed up in the main room, was separated from the annexes on the four cardinal points by dilatations. Only above 13 m was a change to the actual structure without temporary supports. After reaching the intended height, the dome was supported at four attachment points of the columns and at the apex of the four large domes. In a subsequent work step, the pendentives were attached from the ground , thus securing the dome for the long term.

The work on the dome lifting, which began on May 26, 1989, was accompanied with great interest by five international television stations, numerous media representatives and more than 1,000 domestic and foreign architects and civil engineers. A spectator stage was specially set up in front of the construction site. The successful completion of the uplift was completed on June 22, 1989. The top of the dome was 68 m high and up to the top of the cross at a height of approx. 78 m. On June 25, 1989, the first actual liturgy took place in the church under the direction of Patriarch German. Three days before the 600th anniversary of the Kosovo Polje battlefield on the Gazimestan, to 150,000 people gathered on the plateau and in the Church.

In the last step, the pendentif was assembled under the dome at floor level. It represents the transition element between the square floor plan of the church interior and the circular element of the main dome. By attaching the pendant below the dome opening at a height of 40 m, the space was given its final, rounded shape. The task of the pendent is to support the main dome in four positions by hydraulic jacks, which each apply a force of 3,000 kN (altogether 12,000 kN) and other weights, which are carried by the applied mortar, marble cladding of the outer facade and the gold mosaics of the Dome arise, intercept. The 1,100 tonne and 14 m high pendentif has a right-angled base with a span of 24 m between the yokes. As a permanent fastening element, it was pulled into its final position under the dome 28 m using the “chains” method and fastened there. During the two-day procedure at the end of January 1990, a speed of 2.0 m / h was achieved in just 36 hours. The pendulum was also put in place with a minimal tolerance that was significantly less than the required 5 cm.

In total, the six prefabricated assembly elements that make up the dome system weighed 6700 tons.

As an award for the technological innovation in the constructive implementation of the technical assembly of heavy components using the lift-slab method, the engineers responsible received the First Prize of the Association for Civil Engineering in Yugoslavia in 1989 for their structural engineering achievement.

After the silhouette of the church with the mounting of the dome was completed, the further work was suspended for practically the entire following decade.

Completion of the external work 1990–2004

With the beginning of the civil war in Yugoslavia and the UN economic embargo against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1992, construction work slowed down considerably in the early 1990s. In 1991 90% of the work on the concrete reinforcement was completed. Further construction work continued until 1996, but under different priorities. The Serbian Orthodox Church made particular efforts to organize smaller building projects in rural areas that were suffering from the war situation. as well as help for refugees and displaced persons. Finally, the architects and construction workers at the St. Sava Cathedral had to be laid off in 1996 due to lack of funds, and the construction site was abandoned for several years.

In particular, during this time the marble and granite slabs were stored around the church, which for years was a peculiar sight as a concrete shell in the center of Belgrade. During the NATO bombing of Serbia and Belgrade, a liturgy against the war took place in the church on April 20, 1999, in which 100,000 people from Serbia and Montenegro took part despite the danger of bomb alarms. The further construction of the church became known on April 5, 2000. The Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church also determined the personnel changes in the management of the building. Vojislav Milovanović replaced Branko Pešić as the organizer of the construction site, who now only had an advisory role. The shape of the crypt also underwent changes, which according to Pešić's original idea took up 2,300 m² and now with a changed floor plan 1,600 m².

Before the war, Greek marble of the provenance “Ajax” by the manufacturer Laskaridis from Kavalla was chosen for the exterior cladding, after the war a similar marble from Drama of the provenance “Volares” was chosen. The vaults and wreaths of domes, semi-domes, bell towers and window yokes were made with red Italian granite, the base with black Jablanica granite and completed in 2004. In the same year the building was officially inaugurated. In 2003, mass for Serbia's Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić , who died in an assassination, took place in the church .

Interior work from 2004

The interior work of the cathedral included the excavation and installation of the 1,800 m² crypt, stone masonry and mosaic work as well as the planning of the iconostasis. After the crypt was finished in 2015, stone carvings remained on the consoles, capitals and rosettes, and in particular the gold mosaics. Gazpromnjeft initially paid for the mosaic design in the amount of 4 million euros. This only completed the gold mosaic in the dome. In order to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church in time in the cathedral in 2019, the Serbian government approved 11 million euros from the state reserve in December. With this money, the sanctuary should be able to be completed, for which a project of the Russian Academy of Arts under the direction of Nikolaj Muchin is available. According to unofficial information from the newspaper Blic, the cost of construction by the end of 2017 was 150 million euros.

As of April 2016, in preparation for the mosaic decoration, three square webs of 11 and 11, respectively, over the diameter of the dome were installed inside the openings of the lower drum cassette. 2 × 10.5 tons of weight pulled in. A metal floor was placed over the bridges at a height of 42.90 m, on which a modular scaffolding stood up to a height of 59.08 m. Until January 2018, a specially constructed freight elevator was used to reach the work area and to transport work materials, which was constructed by the chief civil engineer of the cathedral building, Milan Glišić, in the middle of the church under the apex of the dome. The freight elevator was fixed to the supporting pylons of the dome with 50 mm thick steel cables that could withstand up to 5.5 tons of tensile load.

Dimensions and details

technical description

The architecture of the Cathedral of Saint Sava is based on the dimensions and style of the former Byzantine church of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. It was built in the style of Neo-Byzantineism with selectively adapted elements of postmodernism. The church has three levels: crypt, ground floor and choirs. The crypt consists of two closed units, the memorial church of the Holy Prince Lazar and the burial place of the patriarchs of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The stair entrances to the crypt are in the pillars in the northwest and southwest. The ground floor of the church has three entrances to the north, west and south. At each entrance there is a vestibule, which is framed by four domed tower pillars of the church. The stairs to the galleries and crypt are located in the southwest and northwest pillars. Passages in the pillars connect individual parts of the room without entering the main room of the church. In the chancel there is a patriarchal throne and seats for a large number of bishops. Behind the chancel the treasury of the church connects as an arched passage. It is the repository of liturgical objects that are in use during masses. Galleries and chorales lie above the vestibules. Passages in the western pillars of the church connect the galleries with one another. There are chapels above the Diakonikon and the Proskomidie . You will u. a. used as a baptistery. The 44 m high bell towers, which support the dome in their pillars, connect via staircases in the pendentives to the circular gallery in the dome. Rosettes in the dome arch corridor and in the dome gallery provide a view of the church interior. On the outside of the dome, a circular gallery serves as a viewing platform over the city. By the end of 2020, three lifts for 9 people each, two for tourists and one for the choirs will be installed in the church. Visitors to the church will be able to use the lifts to tour the inner and outer domed gallery immediately after the inauguration of the church in October 2020.

Dimensions

The church is one of the largest houses of worship in the world. With the dimensions of 91 m × 81 m compared to 77 m × 71 m in the Hagia Sophia and a built-up area of 4830 m 2 by 7,570 m², it roughly corresponds to the dimensions of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. The crypt occupies an area of 1,600 m² at a level of 6 m. The three galleries on the first level above the three cross arms of the conches have a total area of 1,276 m². The choirs find their place on them during the divine service liturgy. There should be a maximum of 12,000 people in the church. Originally a new patriarchal palace , a theological faculty and an ecclesiastical museum were planned next to the church , all in the neo-renaissance style , but due to a lack of financial means and new buildings after the war, these will probably not be possible.

The extensive work that needs to be done in the interior decoration includes the execution of the mosaics, the assembly of the elements of the stone wall decoration, the completion of the galleries and chapels in the vestibules as well as work on the iconostasis and stone baptistery.

Individual units

dome

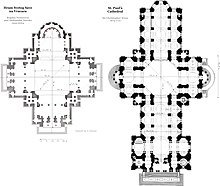

The dome of the church is a pendentive dome over four supporting pillars with an inner diameter of 30.50 m and an outer diameter of 35.15 m, which is almost identical to the dimensions of Hagia Sophia (this had a former dome diameter of 33 m) . The dome stands on four 37.70 m high bays, the square above the central space under the dome has a side width of 39.72 m and a floor area of 1,578 m². The double-skinned dome is a total of 27 m high and reaches a height of 67 m on the outside and 64.56 m on the inside. This means that it has a slightly higher peak height than in Hagia Sophia (67 m to 56 m). The dome of Hagia Sophia is particularly flat, as it was built with a barely pronounced drum. The dome in the cathedral of St. Sava has a pronounced drum with 16 inward-facing rosettes in the lower part and 24 large gallery windows in the upper part. On the outside, the convex hemisphere of the dome fades into a short concave vault. Inside the dome, between the shells, there is a 2 m wide technical passage with a passage to the cross. The four-ton gilded cross of the main dome is 12 m high with anchoring and 10 m high as a visible silhouette above the dome. The cross was created from the connection of the work in the sculptural idea of Nebojša Mitrić with the architectural concept of Branko Pešić. It was manufactured in Prva Iskra - Barić by the Modul company. The 12 m high cross is 5 m wide, the golden apple is 2 m in diameter. The 4 ton steel cross came as a blank in a special hanger at the cathedral construction site. Here it was worked on by Sava and Dragomir Dimitrijević, who also gilded the other 17 crosses of the same shape in the church, within several months. At the beginning of 1989 it was hoisted onto the dome with the help of a crane and fastened there in just 15 minutes. Nebojša Mitrić killed himself on August 23, 1989 in response to the negative media criticism that sparked his modern design. Today his cross is seen as a stylistic achievement and is worn as a copy of the episcopes of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Mitrić was first and foremost a sculptor of miniatures and medals (including those of the Olympic Games in Sarajevo 1984). He was the only one of his Jewish family in Belgrade to survive the Holocaust and grew up with a host family.

In general, the dome of St. Sava Cathedral is the largest in an Orthodox church. Only the Hagia Sophia, which is now a museum, has a larger diameter, which was originally 33 m and can be precisely determined today via the reconstructed relationship of 105 Byzantine feet span to 0.313 m Byzantine feet. Its dome is also the largest to this day, which was built over just four bases. Today it has a slightly elliptical shape with diameters of 31.24 m and 30.86 m.

By way of comparison, the large historical domes of St Paul's Cathedral (30.8 m), in the Florence Cathedral (43 m) and in St. Peter's Basilica (42 m) were partly built with significantly larger dimensions. However, none of these domes rests on just four pendants over four supports. The floor plans of the domes in St Paul's Cathedral and Florence Cathedral are octagonal with eight pillars and eight pendentives, the dome in St. Peter's Basilica is sixteen-sided and also has eight pendentives. Significantly, the 24 m wide domed yokes in the Cathedral of St. Sava are one meter further (24 by 23 m) as in the much larger dome of St. Peter's Basilica. The height of the main yokes in the St. Sava Cathedral is 37.70 m, but significantly below that of St. Nevertheless, the space-dominating effect of the dome in the Cathedral of Saint Sava, as it is built over a square central space and has equal or wider domes, is more pronounced than in the elongated nave floor plans of St. Peter's Basilica, Florentine Cathedral and St. Paul's Cathedral.

In the Berlin Cathedral , which is also part of Historicism , with an inner dome diameter of 30.7 m, which has roughly the same diameter as the Belgrade Cathedral Church, the dome yokes are 12 by 24 m, only half as wide as in the Cathedral of Saint Sava. The dome square of the two central buildings in the Cathedral of Saint Sava is larger, so there is space for up to 10,000 people standing, while the Berlin Cathedral was designed for 2,100 seats. Compared to the largest built domes of Orthodox cathedrals, the one of Saint Sava with 35.5 m outside and 30.5 m inside exceeds both that of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow with 29.8 m outside and 25 m inside, the Nikolai Naval Cathedral with a diameter of 29.8 m outside and 26.7 m inside, as well as that of St. Isaac's Cathedral in Saint Petersburg with 25.4 m outside and 22.75 m inside. The clear width of the yokes of St. Sava with 24 m remains well above the 15 m in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior. If the factor between the diameter and the greatest clear width of the zygomatic arches is included as a parameter of the visible space under the dome, the Hagia Sophia comes to a value of 1.0, the cathedral in Florence to 2.17, the St. Peter's Basilica to 1.65 and the Cathedral of Saint Sava on 1.3. The impression of the dematerialized, floating dome of the Hagia Sophia is well explained by this factor, as it creates a uniform and expansive dome space in addition to the structural solutions to conceal the load-bearing structures to explain the architectural effect. This is also true in the cathedral of Saint Sava, whose space under the dome shows a special width and harmony, while historical churches with larger factors between the dome diameter and the zygomatic arch widths such as in the cathedral in Florence, whose dome is actually an oversized crossing dome on a Gothic nave , cannot develop this effect on the viewer.

This makes the dome of the Church of St. Sava the second largest after Hagia Sophia, which stands on only four pillars. Since a certain dimension of the dome diameter was not specified anywhere in the tender, but the design in its final version was based heavily on the Hagia Sophia, its dome was taken as the direct model in its dimensions. Aleksandar Deroko wrote in 1985 that the diameter of the dome of the Cathedral of Saint Sava is 30 m and that of Hagia Sophia is 32 m, which suggests that a comparable monumentality to the Hagia Sophia was sought.

Bell towers

The church has 10 towers; four are grouped as domes around the main dome, two around three of the four conches . All of them have gilded crosses that are shaped after the main cross. The church bells are in the two large west towers.

columns

As an analogy to the architectural model of the Hagia Sophia, the Naos and vestibules are separated by a row of four pillars each. A total of twelve green marble columns separate the naos and vestibules. In the main portal in the entrance area of the western vestibules there are also four similar green marble columns. Six red Veronese marble columns were used in the chancel. All columns were installed during the first construction phase in 1940. The fighter capitals of the columns with Christian symbols, chthonic animal motifs and floral ornaments were made by the Swiss sculptor Pino Grassi.

ornamentation

The relief ornamentation of the building was designed by Aleksandar Deroko in the 1930s and executed by Pino Grassi. According to Deroko's specifications, nine of the large column capitals were built by 1943. From 2004, the eight biforias and the column capitals that were still missing were added to Deroko's sketches. The interior has a total of 26 column capitals on the ground floor, plus six on the outside of the three entrances. On the gallery level, there are two composite columns with quadruple capitals in the north and south galleries. The outer sides of the galleries have large marble bas-reliefs. The 24 marble columns in the walk-in inner circular gallery below the dome at a height of 40 m also have marble capital ornaments. 12 rosettes, which are executed below the gallery in the dome, allow a view into the interior of the church later. Dragomir Acović was appointed the author of the sketches, which Deroko no longer carried out , and Nebojša Savović Nes is the main person in charge of the stone carving.

Bronze reliefs are placed on all the entrance doors of the church, and mosaics are provided for the lunettes above the doors. Stone sculptures are mounted over the windows and rosettes decorated with aluminum.

Byzantine capitals and fighters were partly made in 1940 according to the specifications Derokos

crypt

In the crypt, the burial church of the Holy Martyr Lazar will take the central place. The crypt is intended as a cultural meeting point for concerts and the exhibition of the treasury of the Serbian Orthodox Church. While the naos of the church is decorated with mosaics, frescoes are planned for the crypt . The walls are also covered with travertine and limestone .

The architect Dragomir Acović is responsible for the mosaics of the church and the entire interior.

Windows and doors

The frames of the windows and rosettes of the church are made of anodized aluminum, as they were already used by Pešić in the outer cladding of the Beograđanka. The windows themselves are made of crystal glass. Instead of the aluminum portals originally planned, large wooden doors were installed.

ground

The heated floor will be decorated on over 3600 m², of which 1600 m² will be executed in a complex, ornamentally designed inlay technique with different colored architectural stones.

Mosaics

Political implementation

Information about the implementation of the mosaic interior design by Russia, which included assumption of costs by the Russian gas giant Gazprom, became public in 2010 when the Serbian daily Danas linked the visit to Zurab Tsereteli in 2009. During the state visit of Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2011, he assured him that the costs would be covered during the tour of the church. An estimated 30 million euros would be necessary for the complete execution by Russian mosaic specialists. The design of the depictions of saints and salvation history will continue in an initial phase until 2019. Gazprom provided the necessary funds of over 4 million euros for the dome mosaic. To this end, the company used its own representatives at the meetings in the Russian Art Academy and the Friends' Association for the construction of the church. A central meeting between the director of the Russian government agency Rossotrudnicestvo Lubov Nikolaevna Glebova, who was appointed by Putin as the direct commissioner for the interior decoration of the church, took place in Belgrade on November 13, 2015 in the presence of the President of Serbia and the Serbian Foreign Minister. For further completion, on January 17, 2019, Vladimir Putin once again promised the Russian state to take over 5 million euros. In symbolic form, he placed a mosaic stone in the representation of the mandylion during his visit to the cathedral . This will later be installed in the cornice of the dome.

competition

For the mosaic design, a competition was held in which 50 entries were submitted. The Russian President Putin made this possible with the decree Pr-1197 of April 29, 2011. An intergovernmental contract between the foreign ministries of Russia and Serbia was concluded on March 19, 2012 for the urban development transfer of the work to Russia. The competition, hosted by the Russian Ministry of Culture, opened on September 23, 2014 in the gallery of the Russian Art Academy (ul. Prechistenka 19) in Moscow. Artists from Moscow, St. Petersburg, Yaroslavl and Minsk took part. On October 5, 2014, Nikolaj Aleksandrovič Muchin was selected as the winner by a jury. His draft was presented to the President of Serbia and the Serbian Foreign Minister and Metropolitan Amfilohije on October 6th. In form and style it follows Byzantine gold mosaics of the 12th century.

Authors

The originators of the mosaics are the Russian Nikolai Aleksandrovich Muchin (Николай Александрович Мухин, * 1955), who had previously co-designed the frescoes of the Moscow Christ the Savior Cathedral , as well as Yevgeniy, Nikolajewitsch Maximow (Евгенавикикикоо) (Евгенавич Евгенавикиково (Евгенавич Мухикович48 Painting of the Russian Art Academy . At the Russian Art Academy, Muchin's and Maximov's employees worked out a 1:10 scale model of the future mosaics.

Structural implementation