Eduard Gaertner

Johann Philipp Eduard Gaertner (born June 2, 1801 in Berlin ; † February 22, 1877 in Flecken Zechlin ) was a German vedute painter of the 19th century.

His views of Berlin, created between 1828 and 1870, provide information about the historical appearance of the city in the Biedermeier period . Gaertner completed his apprenticeship at the Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Berlin . He then became a student of the royal court theater painter Carl Wilhelm Gropius . His teacher brought Gaertner into contact with the Berlin artistic elite. From 1822 Gaertner regularly exhibited his pictures at the Academy of Arts . The institution gained public recognition for his art. In the 1820s he received his first commissions from the Prussian royal house and went on a study trip to Paris. After his return he settled in Berlin as a freelance painter and specialized primarily in Berlin cityscapes. The Berlin panorama from 1834 is considered to be his main work from this period . At the end of the 1830s he went on business trips to Russia. In the 1840s, Gaertner's art lost its attention at the royal court. The artist turned more to a middle-class clientele and expanded his repertoire to include depictions of landscapes and interiors. Since the 1850s, photography made Gaertner's architectural painting increasingly unprofitable. In 1870 he withdrew from Berlin and spent the last years of his life in Zechlin.

Life

Origin and childhood (1801–1814)

Eduard Gaertner was born on June 2, 1801 in the Prussian capital Berlin. He was to remain closely connected to his hometown throughout his life and, according to the art historian Helmut Börsch-Supan , “understood like no other painter how to grasp the uniqueness of the city”. In Berlin he was exposed to a variety of architectural stimuli that trained his sense of “discovering the beautiful in reality” (according to Börsch-Supan). The great architectural painters of the 18th century, especially Canaletto and Francesco Guardi , became his models early on. Gaertner experienced Berlin as a city in transition : the royal residence city lost its manageability due to the industrialization that began slowly in the 1930s . In the cultural field, the bourgeoisie broke the dominance of the court and nobility. On the outskirts of the city, the slums of artisans, day laborers and factory workers emerged. Political and social tensions were part of the appearance of the city and should be reflected artistically by Gaertner.

The path to becoming an artist was by no means mapped out for him. Eduard Gaertner came from a humble background. His father Johann Philipp Gärtner (that's the official spelling), born on January 9, 1771, was an English master chair maker who moved to Berlin. In the course of the Napoleonic occupation of Berlin in 1806, the economic conditions deteriorated so much that Johann Philipp Gärtner became unemployed. In order to ensure that the family was provided for, his wife Caroline Gaertner left Berlin with the young Gaertner and settled in Kassel . She worked there as a gold embroiderer and, at the age of 10, enabled Eduard Gaertner to be taught drawing by the Kassel court painter Franz Hubert Müller . Mother and son stayed in Kassel, the capital of the short-lived Kingdom of Westphalia , until 1813, when Napoleon's defeat in the Wars of Liberation became apparent.

Education (1814-1824)

When Eduard Gaertner began his six-year apprenticeship at the Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur (KPM) in 1814 , Berlin experienced a phase of economic recovery. Since the warlike burdens no longer existed - apart from Napoleon's brief return - the bourgeoisie and the nobility began to buy porcelain again. KPM was therefore interested in training new apprentices and hiring them as specialists. Gaertner also benefited from this development as a decorative painter in the manufactory. According to the art historian Helmut Börsch-Supan, Gaertner's abilities, the high “precision of drawing and the sense of surface stimulus” go back to this training. Other Berlin architectural painters such as Johann Heinrich Hintze also began their careers at KPM. Eduard Gaertner himself was of a different opinion: what he learned in the porcelain factory was "apart from a superficial teaching of perspective for [his] career (was) more of a hindrance than a benefit, since [he] only had to make rings, rims and cranks". In the manufactory, Gaertner made friends with Gustav Taubert , the head of figure painting and later director of KPM. He adopted portrait painting techniques from him .

When Gaertner had just finished his apprenticeship at the porcelain factory in 1820 and was not yet a professional artist, he drew a 15.6 × 9.4 cm self-portrait. In the pencil portrait, the twenty-year-old presents himself “sitting on a high-legged stool” (according to Irmgard Wirth ), assuming the posture of a rider. The book placed on the seat of the stool and "the regular hatching" show him more as an academic and less as an artist. Nevertheless, Gaertner was already experimenting with perspective in the picture. His legs and hands appear disproportionately wide compared to the upper body. The art historian Johanna Völker therefore suspects that the artist worked with a convex mirror .

In 1821 Gaertner moved to the studio of the royal court theater painter Carl Wilhelm Gropius . He worked there until 1825 on the design of painted stage sets . It was to this activity that Gaertner owed his eye for architectural perspectives and their realistic reproduction. Through Gropius he met the architect, painter and stage designer Karl Friedrich Schinkel . He designed the sets, which Gaertner completed. In addition to working at Gropius, Gaertner also attended the first drawing class at the Akademie der Künste in 1822 . Although Gaertner succeeded in being transferred, he broke off the semester again in 1823.

Beginning artist career and study trip to Paris (1824–1828)

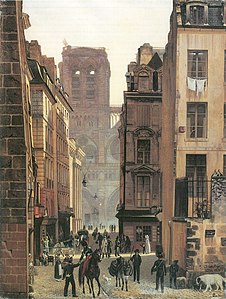

|

| Rue Neuve-Notre-Dame in Paris |

|---|

| Eduard Gaertner , 1826 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 44 × 33 cm |

| Ladies' wing in Sanssouci Palace , Potsdam |

In 1824 Gaertner received an order from the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III for the first time . It was supposed to document the interior of the previous building of today's Berlin Cathedral , which was redesigned by Schinkel in 1816/1817 . Before Gaertner began working on the oil painting, he made a 37.8 × 34.2 cm pencil drawing as a template, which has been preserved in the Märkisches Museum . It only differs from the later painting in a few details. Only a few people are depicted on this sketch, so that the viewer's attention is drawn entirely to the classical architecture. In the 77 × 62 cm oil painting, the line of sight falls from the location of the north gallery onto the organ and the altar of the church. A bright beam of light penetrating from the right side illuminates the row of seats in the nave. The shadow of the window bars can be seen on a column on the right edge of the picture. The king had the painting hung in today's Kronprinzenpalais . During the exhibition at the Berlin Academy in 1824, it became known to a wider public and brought Gaertner further orders. In 1825 he was able to afford a three-year educational trip to Paris , following the example of his teacher Gropius.

During his study trip, Gaertner only stayed temporarily in the French capital. He used the opportunity several times to visit cities such as Nuremberg , Heidelberg , Ghent , Brussels and Bruges , where he was particularly drawn to the buildings of the late Gothic . Paris as the artistic, economic and political center of France must have made a great impression on Gaertner. Around 890,000 people already lived in the city - more than four times as many as in Berlin. The core of the city was still largely dominated by medieval buildings that were about to fall into disrepair. It was precisely this cityscape that had attracted English painters and watercolorists from the 1800s . Under their influence, Gaertner finally began to turn away from the interior depictions and turn to the city vedute .

Gaertner lived in the Parisian studio of the landscape painter Jean-Victor Bertin . Although this was not a vedute painter, he probably caused Gaertner to be more interested in painting. Previously, Gaertner had preferred to work on watercolors over paintings. In Paris, however, as Irmgard Wirth emphasizes, he learned to achieve “air and light effects using only the means of color”. From now on, according to Wirth, Gaertner's paintings are no longer characterized by a “cold, hard and evacuated” charisma.

Inspired by the Parisian cityscape, he made numerous paintings and watercolors. In 1827 he sent some of these copies to a Berlin academy exhibition. There the art critics were impressed by Gaertner's skills. For example, the Berliner Kunstblatt praised the successful rendering of light and air. The most famous of Gaertner's views of Paris shows the view from Rue Neuve to Notre Dame Cathedral . The cathedral itself takes a back seat; it is shrouded in haze, which is intended to underline its spatial distance from the viewer. The left block of the street, on the other hand, is touched by the “afternoon, subdued” sunlight. As in many of his works, Gaertner highlights everyday street scenes: laundry is hanging on the windows, a donkey is being led through the street, a man is roasting chestnuts "on hot coals"; Dogs and cats liven up the scene, as do uniformed people.

Professional establishment and starting a family (1828–1830)

|

| The Klosterstrasse |

|---|

| Eduard Gaertner , 1830 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 32 × 44 cm |

| National Gallery , Berlin |

After his return from Paris in 1828, Gaertner tried to be professional and family independent. In Berlin he worked as a freelance artist. His numerous views of the Prussian capital were well received by the Berlin bourgeoisie, but also by the royal family. This and his membership in the Berlin Artists 'Association founded in 1814 (not to be confused with the Berlin Artists' Association ) gave him access to the social gatherings of the urban artistic elite. Gaertner maintained contacts, among others, with Karl Friedrich Schinkel, Franz Krüger , Christian Daniel Rauch , Karl Eduard Biermann , Gottfried Schadow and Johann Heinrich Hintze . Within this circle he took part in numerous invitations and excursions into the Berlin area.

He often had his acquaintances immortalized in paintings. An example of this is the painting Die Klosterstrasse from 1830: In the middle of the painting, the painter Franz Krüger, known for his horse views, is riding across the street . Kruger turns to greet Gaertner, who is standing to his right and reciprocates the gesture with a drawn cylinder . To the left of a carriage, Rauch - recognizable by his white trousers - is walking in the middle of a group of people. On the right side, in front of the facade of the trade institute , Schinkel accompanies the ministerial official Peter Beuth . Some of the people shown lived or worked in Klosterstrasse. Gaertner placed Rauch in front of his home and studio. Schinkel designed the architecture of the industrial institute; Beuth was the founder of the same complex that dominates the right side of the painting. Gaertner demonstrates in the painting that he saw himself as an artist on a par with Krüger and Schinkel.

In 1829 he married the 21-year-old Henriette Karel. With her he had twelve children, eight of whom reached adulthood, five sons and three daughters. As Gaertner's diary entries show, he was mainly concerned with family life on holidays and Sundays. During the working weeks, however, he primarily devoted himself to his numerous works of art and preliminary drawings. For example, the painting of the Spittelmarkt and the Berlin panorama were created around the same time. Some of Gaertner's sons made careers: Eduard Conrad Gaertner officiated as German consul on the Japanese island of Hokkaidō between 1863 and 1871 . Gaertner's eldest son Philipp Eduard Reinhold followed his brother Conrad to Japan and built a large plantation there. The youngest son Otto Eduard Philipp Gaertner emigrated to the United States of America, where he became a well-known portrait painter.

Time until the trips to Russia and the Berlin panorama (1830–1837)

In the 1830s, Gaertner was at the height of his success. Alongside Domenico Quaglio , he was the most important architectural painter of the German Confederation. He portrayed Biedermeier Berlin as an idyllic residential city that was comparatively little affected by industrialization . In many places, squares and streets still looked small-town. Schinkel's recently erected buildings were also a popular motif for the artist. His four writing calendars, which are now kept in the National Gallery , mainly originate from this period of his work . With their short entries from the years 1834, 1836, 1838 and 1842 they provide insights into Gaertner's life. In it he paints the image of himself as a pious and hardworking personality.

Among other things, the writing calendars provide clues about the origins of one of his most important works: the six-part Berlin panorama from 1834, which shows the all-round view from the roof of the Friedrichswerder Church , built by Schinkel between 1824 and 1830 . As a basis for this, Gaertner made a drawing on canvas, to which he later applied an underpainting . Then he brought the panorama to the roof of the church. There he set up a "shack" that was supposed to protect him from wind and weather. Gaertner worked on the roof for about three months on the panorama. He completed his work in his studio at the end of 1834. The panorama was made up of six panels because Gaertner was unsure whether a 360 ° panorama that could be walked on would find a wealthy buyer. Individual picture panels offered the advantage of being able to sell them to various interested parties and place them in living spaces. After the first three picture panels, the artist King Friedrich Wilhelm III. win as a buyer. The finished panorama found its place in 1836 in Charlottenburg Palace.

The panels of the panorama should (according to Ursula Cosmann) “create the illusion of standing on the roof of the church”. For this purpose, the flat gable roof, the pinnacles , two towers (see the west view of the panels) and the parapet form part of the panorama. At the same time, they make it easier for the observer to “determine the exact location” (according to Gisold Lammel). In the foreground, the north panels show how the natural scientist Alexander von Humboldt explains the view of the Forum Fridericianum to a couple on the zinc roof , pointing to a telescope. Hedwig's Cathedral can be seen on the left side of the north elevation , followed by the royal library in the back right and the royal opera in the middle . On the right side finally appears arsenal . On the east side you can see the Lustgarten with today's Altes Museum and the classicistic predecessor of today's Berlin Cathedral . On the far right you can see the Berlin City Palace , which also protrudes into the south view. This is dominated in the background by the as yet unfinished Berlin Building Academy . The artist has immortalized himself in the foreground. To the left of him, a “green drawing folder” (according to Ursula Cosmann) bears the inscription Panorama von Berlin . Further to the right, the towers of the Gendarmenmarkt are in the distance . The roof and the gable portico of the theater are visible between the German and French cathedral there . In the west view, which is dominated by the towers of the Friedrichswerder Church, you can see Gaertner's son climbing to the top of the roof, carrying a saber in his hand. On the left side of the west elevation, Schinkel and Beuth are talking to each other.

By highlighting the university, opera, old museum, theater and building academy, Gaertner put bourgeois Berlin in the foreground. In contrast, he pushed the Berlin City Palace as the center of the Prussian monarchy “to the edge” of the boards. According to the art historian Birgit Verwiebe, this can be understood as a hidden criticism of monarchical politics. In addition, the panorama allows rare insights into everyday work: construction workers and roofers stand on the scaffolding of the building academy. In the east view, below the pleasure garden, boat drivers transport barrels on the Spree. On the right panel facing south, a woman is knocking out bedding in the lower right corner. Looking out the window, a man is smoking his pipe. Several carts can be discovered at the Forum Fridericianum, between the university, Hedwig's cathedral and the opera.

Trips to Russia (1837–1839)

|

| left side of the Kremlin panorama in Moscow |

|---|

| Eduard Gaertner , 1839 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 60 × 110 cm |

| Schinkel Pavilion , Berlin |

After the success of his Berlin panorama, Gaertner tried to establish contacts with the Russian court of the Tsars. He wanted to make use of the family connections of the Hohenzollern dynasty, because Tsarina Alexandra Feodorowna was a daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm III. He wanted to sell her a second version of the Berlin panorama. Contrary to what was assumed in older literature, Gaertner traveled - as the art historian Wasilissa Pachomova-Göres has worked out - to Russia without an order from Tsar Nicholas I and his family. Whether the tsar would buy his work from him remained an open question for the time being. Gaertner took this risk anyway, because his teacher Gropius and artist friend Krüger had been doing business successfully in Russia for years. In 1837 Gaertner went to Saint Petersburg and was able to sell his panorama replica. The tsar made the portrayal of his wife as a present. The impressions of the trip to Russia, some of which Gaertner captured in landscapes and cityscapes, which are mostly lost today, encouraged him to make further stays in Moscow and Saint Petersburg in 1838 and 1839.

The "spaciousness and exotic architecture" of Moscow ( Dominik Bartmann ) made a deep impression on Gaertner. Even after his trips to Russia ended, the city remained an important motive for him. An outstanding example of this is his Kremlin panorama from 1839. It is distributed over three picture surfaces, with which Gaertner imitated the sacred form of the medieval triptych . In this way he created a suitable frame for the shiny gold church domes of the Kremlin. In the left part of the picture, the Archangel Michael Cathedral (left) and the diagonal Kremlin wall stand out. The above-mentioned cathedral covers the Annunciation Cathedral and the Great Kremlin Palace in the background . On the right picture you can see some buildings that are no longer there today, such as the Chudov Monastery , consecrated to Archangel Michael, and the Ascension Monastery . The middle picture shows the bell tower Ivan the Great with the tsar's bell that has fallen down . The Assumption Cathedral rises in the background to the left of the bell tower . The carved frame of the painting is gilded and was designed by Gaertner for Friedrich Wilhelm III from the beginning. certainly. As in the Berlin panorama, the Moscow panorama also depicts the everyday life of the citizens: about two children play in front of the Archangel Michael Cathedral. The clergy are shown in black robes. Officers ride through the picture. Citizens wearing tailcoats go for a walk. In the right picture area, Gaertner probably immortalized himself again. He holds a "sketchbook" (Birgit Verwiebe) and turns to the viewer.

Reorientation and style change (1840-1848)

|

| The living room of the master locksmith Hauschild |

|---|

| Eduard Gaertner , 1843 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 25.8 x 32 cm |

| Märkisches Museum , Berlin |

On June 7, 1840 died with King Friedrich Wilhelm III. Gaertner's most important patron . Between the years 1828 and 1840 the king bought 21 paintings from him. The new ruler, Friedrich Wilhelm IV. , Had a different taste in art than his father. He was less interested in vedute of Berlin. Rather, the architectural model of Greece and Italy became the benchmark. Gaertner had never traveled to either country. Interest in art inspired by the Middle Ages also gained in importance at the court under the new king. Other artists such as Johann Heinrich Wärme, Friedrich Wilhelm Klose and Wilhelm Brücke were more able to meet this changed demand than Gaertner. Landscape painting also began to displace architectural images. Since 1840, Gaertner was forced to address a middle-class clientele more than ever before and to expand his artistic repertoire. In the following years he remained a respected painter among the Berlin bourgeoisie, who received numerous commissions. The depictions of private interiors were particularly important to him.

The painting The living room of the master locksmith Hauschild belongs to the interior painting of this time . Gaertner had business relationships with master locksmith Carl Hauschild since the 1930s . During the transport of the two Berlin panoramas, he made his manual skills available to the painter. Hauschild commissioned Gaertner's paintings twice (1839 and 1843), including a view of his living room at Stralauer Strasse 49 in Berlin. Gaertner captures a familiar, intimate atmosphere in the picture. Nothing reminds of the house owner's workshop work. Journeyman and apprentices, who had been an integral part of the craftsman's household for centuries, do not appear. Next to Carl Hauschild (far right) his wife (recognizable by the infant in her arms), mother (far left) and four children are shown. The painting also provides insights into the living culture of the Biedermeier period: the ornate parquet floor, the mahogany furniture and the strong blue wallpaper color express wealth, with which the family wanted to emphasize their unusually rapid social advancement. On the right side of the room, a showcase cabinet displays valuable glass and silver objects. The chest of drawers further back is partly covered by the display cabinet. A sewing table is ready on the floor in front of the mirror . An astral lamp hangs from the ceiling .

In the 1840s, Gaertner made a number of trips; In 1841 he visited Bohemia for the first time ; The Mark Brandenburg followed in 1844 and, from 1845, several trips to the province of Prussia . In the province of Prussia, he combined his skills as an architectural painter with the growing interest of the Berlin bourgeoisie in history and historical monuments. The region was known for its Gothic brick buildings and castles from the time of the Teutonic Order . The many small towns and villages idyllically located on rivers also promoted Gaertner's landscape painting. Medieval dominated cities such as Neidenburg , Gollub and Allenstein brought Gaertner back into cultural awareness with his watercolors and paintings. The city of Thorn developed into the center of his artistic activities in the province of Prussia . In contrast to most other places, their small citizenship was wealthy enough to give gardening orders.

Time of the revolution of 1848/1849

|

| Schildhorn on the Havel |

|---|

| Eduard Gaertner , 1848 |

| Watercolor pencil drawing on paper |

| 21.3 x 29 cm |

| Watercolor collection of the State Palaces and Gardens Foundation, Potsdam |

In 1848 the so-called March Revolution spread to Berlin . How Gaertner positioned himself politically at this time is unknown. There are no written statements in this regard. The art historian Helmut Börsch-Supan concludes from the artist's surviving works of art, such as the watercolor Barricade after Fights in the Breite Strasse , that Gaertner, like many of his contemporaries, was shocked by "the deep gulf between the king and the people". Renate Franke also comes to the conclusion that Gaertner does not classify as a revolutionary. According to her, his “cheerful” and “idyllic” cityscapes speak against a radical questioning of everything that exists. Gaertner's writing calendar rather suggests that he was a “diligent churchgoer” and relied on reforms from above. According to Renate Franke, he saw his state ideal in an enlightened Christian monarchy.

Edit Trost also shares this assessment. Gaertner considered an uprising against the Hohenzollern people to have no chance, which is reflected in two other pictures in addition to the watercolor barricade after fights in the Breite Straße . One of them shows the shield horn monument on the Havel, which was erected in 1844 to commemorate a legend: The Slav prince Jaxa came into conflict with the sovereign, similar to the citizens of Berlin in 1848. Jaxa tried to escape the Brandenburg margrave Albrecht the bear by he swam through the Havel. When he threatened to fail, he is said to have sworn before God to be baptized and to submit to the margrave. Then he managed to reach the safe shore. The Schildhorn monument have seen Gaertner hence as "Christian memorial" (Andreas Teltow). The cross of the monument blocks the direct view of the sun, whose light shines brightly. The shield horn monument stands on hilly terrain and towers over the forests on the banks of the Havel in the back of the picture. The watercolor was never intended for sale and remained in the artist's possession during his lifetime.

1850s and 1860s

|

| Unter den Linden with a monument to Frederick II. |

|---|

| Eduard Gaertner , 1852 or 1853 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 75 × 155 cm |

| National Gallery, Berlin |

As an architectural painter, Gaertner specialized in a sober, realistic depiction of the existing structure. In this way of working, a new technology was increasingly competing with him from the 1850s: photography . In terms of price and time of creation, the pictures of the devices were far less elaborate than the work of an architectural painter. They also recorded the wealth of details of the depicted surroundings in high resolution. As early as 1850, 15 photographers were working in Berlin.

Gaertner also saw photography as a model for his vedute. Photographs did not serve him as direct templates for his views, but enabled him to quickly compare with the objects in his picture. He was able to make corrections and thus increased the authenticity of his works. Gaertner acquired a total of 77 photographs from the Berlin photographers, including what is probably the oldest surviving Berlin photograph, taken in 1851.

In 1852 or 1853 Gaertner turned to a motif that he took up again and again between 1829 and 1861. We are talking about the Berlin boulevard Unter den Linden . The street served as a representative backdrop for royal parades and military parades. In the picture, Gaertner shows the street in this function, albeit in the background. Between the pillared portico of the Royal Opera House and the statue of Frederick the Great, the Prussian king rides towards the city palace, where a military parade is currently taking place. As so often with Gaertner's paintings, strolling citizens can be seen in the foreground.

Retirement in Zechlin (1870–1877)

In 1870 he and his wife left Berlin. The artist, suffering from health problems, chose the “scenic” Ruppiner Seeland (Irmgard Wirth) as his retreat. In Zechlin , which is still relatively remote in terms of traffic , he bought a half-timbered house from his eldest son that offered enough space for a studio and apartment. It is in the immediate vicinity of the local church. Gaertner lived largely withdrawn here. Gaertner also remained artistically active in the small town, but mostly only produced smaller works for his own family and close friends (mainly watercolors and drawings). His increasing poor eyesight made painting difficult. Physical difficulties also ruled out traveling to the surrounding area, so that Gaertner could hardly find any sources of inspiration.

He died on February 22, 1877. His 70-year-old wife and two not yet married daughters stayed in the half-timbered house. Henriette Gaertner then asked the artist support fund of the Akademie der Künste for an annual grant of 150 marks, but her application was rejected. She died in April 1880 and was buried next to her husband's grave in the "churchyard".

Eduard Gaertner seemed to have disappeared from art history. It was not until the German Exhibition of the Century in 1906 that his works were shown again; they were now compared with the art of the great Italian vedute painter Bernardo Bellotto (known as Canaletto). There were fragmentary solo exhibitions again in 1968 and 1977, and a comprehensive retrospective in 2001 in the Ephraim-Palais in Berlin .

Works

Tools

Eduard Gaertner worked with the precision of an architect. As a technical drawing aid for the preparation of his pictures, he very likely used the camera obscura , although he does not explicitly mention it in his work diaries. There, however, expressions such as signs machine and apparatus appear which point to the device, as well as various architectural drawings on tracing paper.

Style change

Soon after 1840 - the year Friedrich Wilhelm III died. - a progressive change in style can be observed in Gaertner's work, which follows the zeitgeist and the personal taste of the new king. The general development went from classicist clarity to a more romantic view of nature and history, to idealizing exaggeration. At Gaertner, there are now landscapes with dramatic cloud sections in which the architecture only plays a subordinate, decorative role. He was a master of the romantic repertoire: steep cliffs, spreading trees (especially oaks), ruins of all kinds, gypsies . These works also had a painterly quality, but were far less admired than the cityscapes of earlier years. Eduard Gaertner is remembered primarily as the architectural painter who carefully observed and portrayed the city of Berlin in a significant period of its history.

Socially critical works

According to the art historian Peter-Klaus Schuster , Eduard Gaertner sympathized with the idea of “an egalitarian bourgeois society whose members should get along in a civilized manner and without domination”. Gaertner also captures the tense political atmosphere in Vormärz with two street views in which students at the entrance gate of today's Humboldt University are talking excitedly at night. They are being watched by police officers who are occupying the area between the university and the academy. The student group is a fraternity that has been banned since the Karlovy Vary resolutions of 1819 .

|

| View of the rear of the houses at Schloss Freiheit |

|---|

| Eduard Gaertner , 1855 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 96 × 57 cm |

| National Gallery , Berlin |

Another illustration that testifies to the artist's anti-court disposition is an oil painting from 1855. The view from the back of the houses at Schloss Freiheit shows town houses that should be demolished because of their proximity to the city palace. The town houses are in the foreground and almost completely cover the city palace except for the dome. While the dome built by Friedrich August Stüler is partially covered by shade, the town houses are in the sunshine. According to Schuster, the painting is a "manifestation of the self-confident bourgeoisie" that demarcates itself from the Prussian government. At the same time, the painting follows the bourgeois educational program in that, according to Schuster, it emphasizes the “exemplary nature of antiquity”. On the left side of the painting there is a marble sculpture on the castle bridge. The winged Greek goddess of victory Nike asks a young man to read to her from her shield. There are the names of Alexander the Great , Gaius Julius Caesar and Frederick the Great . According to a statement in the painting, the citizens should orient themselves to the deeds of these “heroes”. The building academy can be seen on the right side of the painting, slightly covered by trees . The tower of the Petrikirche rises in the background . Construction work on the structure was not completed until 1852, three years after the painting was made. Scenes from everyday life can be discovered on the underwater road ; Carriages and carts are on the move, children are playing on the sidewalk and a man with a black dog leans against the railing. He is probably the client, but whose name is unknown. According to Ursula Cosmann, Gaertner deliberately selected an "area little shown by the architectural painters" for his painting.

Parochialstrasse (1831)

|

| Parochialstraße or Kronengasse with a view of Reetzengasse |

|---|

| Eduard Gaertner , 1831 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 39 × 29 cm |

| National Gallery , Berlin |

The oil painting Parochialstraße , created in 1831, depicts the business life of craftsmen, petty bourgeois and traders in Berlin. The boilermaker leaning against a door on the front left of the picture smokes a pipe. In the center of the picture, firewood is being “sawed and chopped”, while on the right side of the street two men drinking beer are talking in front of a Budike . The two- to three-axle houses line up seamlessly in the narrow alley. In the background, the tower of the Nikolaikirche appears blurred in the fog . In the picture, Gaertner made a point of emphasizing the narrow alley. In order to achieve the spatial depth effect required for this, he depicted the house facades for a shortened perspective. The left and right rows of houses seem to "almost touch" in the background. The sky shines in a blue and white color to match the harmonious street life. The rays of the sun falling into the alley touch the upper floors of the houses and create an "invigorating" effect in the picture. In the back of the picture, light penetrates the alley from Jüdenstrasse . In sync with the light, a woman in a white dress turns into the alley from the left. In fact, the picture not only shows "Reetzengasse", but also Kronengasse in the front part. In 1862 a royal edict united Reetzengasse and Kronengasse under the name Parochialstrasse . There were three versions of the picture: One copy is kept in the Berlin National Gallery, another in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and a third copy was destroyed in the Second World War.

literature

- Robert Dohme : gardener, Eduard . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 8, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1878, p. 381.

- Irmgard Wirth : Gaertner, Johann Philipp Eduard. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 6, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1964, ISBN 3-428-00187-7 , p. 24 ( digitized version ).

- Irmgard Wirth: Eduard Gaertner. The Berlin architectural painter. Propylaeen, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1979, ISBN 3-549-06636-8 .

- Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Volume accompanying the exhibition in the Museum Ephraim-Palais, Berlin, 2001. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-87584-070-4 .

- Frauke Josenhans: Gaertner, (Johann Philipp) Eduard. In: Bénédicte Savoy, France Nerlich (ed.): Paris apprenticeship years. A lexicon for training German painters in the French capital. Volume 1: 1793-1843. De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-029057-8 , pp. 86–90.

Web links

- Works by Eduard Gaertner at Zeno.org .

- Eduard Gaertner - Exhibition in the Museum Ephraim-Palais, Berlin ( Memento from March 24, 2018 in the Internet Archive )

- Literature by and about Eduard Gaertner in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: German Romantics. German painters between 1800 and 1850. Bertelsmann, Munich 1972, p. 85.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster : The "Linden" as an educational landscape. In: Birgit Verwiebe (Ed.): Catalog. Under the linden trees. Berlin's boulevard in views of Schinkel, Gaertner and Menzel. Berlin 1997, pp. 29–40, here p. 29.

- ^ Irmgard Wirth : Eduard Gaertner, the Berlin architectural painter. Propylaea, Berlin 1985 p. 7.

- ^ Arnulf Siebeneicker: Gaertner as an apprentice of the Royal Porcelain Manufactory. In: Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 55–64, here 55–56.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: German Romantics. German painters between 1800 and 1850. Bertelsmann, Munich 1972, p. 85.

- ^ Irmgard Wirth: Eduard Gaertner, the Berlin architectural painter. Propylaea, Berlin 1985, p. 17.

- ↑ Irmgard Wirth: Biographical. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 215-217, here: p. 215.

- ↑ Johanna Völker: Between autonomy and dependence. Artistic careers and social status of Prussian painters in the first half of the 19th century. Franz Krüger - Carl Blechen - Eduard Gaertner. Tectum, Baden-Baden 2017, ISBN 978-3-8288-3923-6 , p. 228.

- ^ Arnulf Siebeneicker: "Rings, Ränder und Käntchens": Gaertner as an apprentice and painter at the Königliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Berlin 1814–1821. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 55–65, here: p. 61.

- ↑ catalog section. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 210-439; here p. 313.

- ↑ Dominik Bartmann : Gaertner's Paris trip 1825-1828. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 65–80, here: pp. 65–70.

- ^ Irmgard Wirth: Eduard Gaertner, the Berlin architectural painter. Propylaea, Berlin 1985 p. 19.

- ^ Edit Trost: Eduard Gaertner. Henschel, Berlin 1991, p. 32.

- ^ Edit Trost: Eduard Gaertner. Henschel, Berlin 1991, pp. 15-16.

- ^ Edit Trost: Eduard Gaertner. Henschel, Berlin 1991, p. 36.

- ↑ Nadine Rottau: Schinkel der Moderne - Business Promotion and Design. In: Hein-Thomas Schulze Altcappenberg, Rolf Johannsen (Ed.): Karl Friedrich Schinkel. History and Poetry - The Study Book. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-422-07163-6 , pp. 227–255, here: p. 230.

- ^ Irmgard Wirth: Eduard Gaertner, the Berlin architectural painter. Propylaea, Berlin 1985, p. 9.

- ^ Edit Trost: Eduard Gaertner. Henschel, Berlin 1991, p. 35.

- ↑ Irmgard Wirth: Otto Eduard Philipp Gaertner - an excursus. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 201–204, here: p. 201.

- ↑ Irmgard Wirth: Eduard Gaertner's last lifetime - attempt to interpret his late move to Zechlin. In: Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 189–194, here: p. 189.

- ^ Edit Trost: Eduard Gaertner. Henschel, Berlin 1991, p. 51.

- ↑ Gisold Lammel: Prussia Artist Republic of sheets up Liebermann: Berlin 19th century realists. Publishing house for construction. Berlin 1995, pp. 27-28.

- ↑ Ursula Cosmann: Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Berlin 1977, p. 16.

- ↑ Gisold Lammel: Prussia Artist Republic of sheets up Liebermann: Berlin 19th century realists. Verlag für Bauwesen, Berlin 1995, pp. 27–28

- ↑ Birgit Verwiebe: Earth dust and heavenly haze - Eduard Gaertner's panoramas. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 97–111, here: p. 106.

- ↑ Wasilissa Pachomova-Göres: Gaertner and Russia. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 113-148, here: pp. 113-114.

- ^ Edit Trost: Eduard Gaertner. Henschel, Berlin 1991, p. 19.

- ^ Dominik Bartmann: City Museum Berlin - Ephraimpalais - Eduard Gaertner. In: Museumsjournal, 2/2001, pp. 64–68, here: p. 66.

- ↑ Birgit Verwiebe: Earth dust and heavenly haze - Eduard Gaertner's panoramas. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 97–112, here: p. 109.

- ↑ Ursula Cosmann: Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877 , Berlin 1977. p. 17.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Eduard Gaertner. Habitats portrayed. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 13–30, here: p. 13.

- ^ Sybille Gramich: Eduard Gaertner and the Berlin architecture painting. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 31–54, here: p. 47.

- ^ Edit Trost: Eduard Gaertner. Henschel, Berlin 1991, p. 20.

- ^ Edit Trost: Eduard Gaertner. Henschel, Berlin 1991, p. 82.

- ↑ Renate Plöse: craft and Biedermeier. In: Helmut Bock, Renate Plöse (eds.): Departure into the civil world. Life pictures from Vormärz and Biedermeier. Münster 1994, pp. 124-144, here: pp. 126-129.

- ^ Irmgard Wirth: Eduard Gaertner, the Berlin architectural painter. Propylaeen, Berlin 1985, pp. 59-60.

- ^ Sven Kurau: Eduard Gaertner's travels in the province of Prussia. New fields of activity, motives, sales markets. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 159–174, here: p. 159.

- ^ Helmut Börsch-Supan: Eduard Gaertner. Habitats portrayed. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, 13–30, here p. 15.

- ^ Renate Franke: Berlin, streets and places. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 274–289, here: p. 286.

- ^ Edit Trost: Eduard Gaertner. Henschel, Berlin 1991, pp. 99-100

- ^ Andreas Teltow: Catalog contribution to the shield horn monument. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 331-332.

- ↑ Exhibit in the online database of the National Gallery in Berlin .

- ^ Irmgard Wirth: Eduard Gaertner, the Berlin architectural painter. Propylaea, Berlin 1985. p. 236.

- ^ Eduard Gaertner as a portraitist. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 175-189, here: p. 189.

- ^ Edit Trost: Eduard Gaertner. Henschel, Berlin 1991, p. 28.

- ↑ Ursula Cosmann: Eduard Gaertner - Berlin pictures. To a collection of early photographs from the artist's possession. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 81–96, here: pp. 81 and 95.

- ↑ Online database of the National Gallery in Berlin .

- ↑ Irmgard Wirth: Eduard Gaertner's last lifetime. Attempt to interpret his late move to Zechlin. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 189–194, here: p. 193.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster : The "Linden" as an educational landscape. In: Birgit Verwiebe (Ed.): Catalog. Under the linden trees. Berlin's boulevard in views of Schinkel, Gaertner and Menzel. Berlin 1997, pp. 29–40, here p. 29.

- ↑ Peter-Klaus Schuster : The "Linden" as an educational landscape. In: Birgit Verwiebe (Ed.): Catalog. Under the linden trees. Berlin's boulevard in views of Schinkel, Gaertner and Menzel. Berlin 1997, pp. 29-40, here pp. 35-40.

- ↑ Ursula Cosmann: Catalog part Unter den Linden In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 246-260, here: p. 259.

- ↑ Ursula Cosmann: Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Berlin 1977, p. 15.

- ↑ according to the art historian Irmgard Wirth

- ↑ Imgard Wirth: Berlin. Streets and squares in the catalog section. In: Dominik Bartmann (Ed.): Eduard Gaertner 1801–1877. Nicolai, Berlin 2001, pp. 274-289, here: pp. 277-278.

- ↑ Exhibit in the collection catalog of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gaertner, Eduard |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gaertner, Johann Philipp Eduard (full name); Gärtner, Eduard (bureaucracy registration error); Gärtner, Johann Philipp Eduard (bureaucracy entry error) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German painter and lithographer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 2, 1801 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Berlin |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 22, 1877 |

| Place of death | Spots Zechlin |