emotion

Emotion describes a psychophysical movement that is triggered by the conscious or unconscious perception of an event or situation .

The emotion or affect is to be distinguished from feeling or feeling. The concept of feeling is the more general term that includes a wide variety of psychological experiences , such as B. jealousy , pride , insecurity , enthusiasm and melancholy . In contrast to this, the term “great feeling” has become established as an emotion and thus designates a clearly perceptible physical change in muscles , heartbeat, breathing , etc., which can be demonstrated with measurements of neurophysiological parameters.

Scientists still disagree about whether there are patterns of physiological changes that allow an unambiguous diagnosis of an emotion. In the meantime, several researchers speak of "basic emotions" to denote that there are very basic whole-body programs (physiological, hormonal, muscular).

An emotion

- is behavioral,

- varies in expression with the importance of the situation,

- consists of a specific physical activation that serves to adapt to the situation,

- can be located mainly in the limbic system ,

- is felt primarily as muscle activity,

- is measurable in the release of different neurotransmitters ( serotonin , adrenaline , oxytocin , etc.),

- can be consciously perceived and, in contrast to affect, be influenced.

Emotionality and the adjective emotional are collective terms for individual peculiarities of the emotional life, affect control and dealing with an emotional movement.

etymology

The foreign word emotion designates a feeling, a movement of mind and emotional excitement. The German word is borrowed from the synonymous French émotion , which belongs to émouvoir (dt. To move, excite ). This word comes from the Latin emovere (dt. Move out, dig up ), which is also included in the word locomotive . For the linguistic expression of emotions, the Swiss philosopher Anton Marty coined the term Emotive (Latin: e-motus for German: moved out, shaken ). This includes, for example, an exclamation, a request or a set of commands.

History of the concept of feeling

Already in ancient times , the philosophers Aristippus of Cyrene (435–366 BC) and Epicurus (341–270 BC) described "pleasure" or (depending on the translation of Epicurus) also "joy", "pleasure" (hêdonê) as an essential characteristic of feeling. As "unclear findings" and irrational and unnatural emotions were (about 350-258) determines the feelings of the Stoics; the pleasure principle of the Epicureans is called into question. The older philosophy and psychology treated the subject of emotions and feelings preferably under the term “affects” (Latin affectus: state of the mind, Greek: pathos; cf. affect ) or “passions” and here above all under the point of view of ethics and life skills . “The definition of the concept of affects has fluctuated many times. Sometimes the affects are conceived more narrowly only as emotions, sometimes they are further thought of as volitional processes, sometimes they are defined as temporary states, sometimes as permanent states and then mixed with the passions. "(Friedrich Kirchner, 1848–1900) . For the Cyrenaics (4th century BC), two affects were essential: displeasure and pleasure (ponos and hêdonê). Even Aristotle (384-322) meant by emotions psychic experience, the essential characteristics are pleasure and pain.

Descartes (1596–1650) distinguished six basic affects: love, hate, desire, joy, sadness, admiration. For Spinoza (1632–1677), on the other hand, there were three basic affects: joy, sadness and desire. Even Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) saw the feeling as emotional Grundvermögen of pleasure and pain, "For all the mental faculties or abilities can be attributed to the three which can not be further derived from a common reason: the faculty of cognition, the feeling of pleasure and reluctance and the ability to desire ”.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) did not make a distinction between the emotional and the cognitive aspect: "Behind the feelings there are judgments and valuations which are inherited in the form of feelings (likes, dislikes)."

A much-noticed attempt of the present was the multi-part justification of the essential factors of feeling by Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) through his system for describing the emotions in three dimensions of pleasure / displeasure, excitement / calming, tension / release. Another influential attempt to explain it comes from the American psychologist and philosopher William James (1842-1910). James believed that without physical reactions, feelings or emotions would not even arise (ideomotor hypothesis). For him, emotions are nothing more than the feeling of physical changes. According to James, we don't cry because we are sad, but we are sad because we cry; we don't run from the bear because we are afraid, we fear because we run away.

Psychologists such as Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850–1909) and Oswald Külpe (1862–1915) represented the one-dimensional model of pleasure and displeasure. The psychologist Philipp Lersch (1898–1972) argued against it: “It is obvious that this point of view becomes banal if we apply it to the phenomenon of artistic emotion. The artistic emotion would then be just as much a feeling of pleasure as the pleasure of playing cards or enjoying a good glass of wine. On the other hand, impulses such as anger and remorse would be thrown into the one pot of unpleasantness. In the case of religious feelings, however, as well as feelings such as respect and reverence, the determination of pleasure and displeasure becomes impossible at all. "

Franz Brentano (1838–1917) assumed that the assignment of feeling and object was not contingent, but could be correct (“love recognized as correct”). Similarly, Max Scheler (1874–1928) and Nicolai Hartmann (1852–1950) saw feelings in the so-called “feeling for value” as appropriate characterizations of value experiences (cf. “Material ethics of values”, “Values as ideal being in oneself”).

For Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) too , feelings are essentially to be equated with pleasure and displeasure ("pleasure-displeasure principle"), with the variant that every sensation of pleasure is essentially sexual. Freud was of the opinion: "It is simply the program of the pleasure principle that sets the purpose of life - there can be no doubt about its usefulness, and yet its program is at odds with the whole world."

Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) also emphasized the role of pleasure and displeasure, but doubted that a definition would ever “be able to reproduce the specifics of feeling in a reasonably sufficient way”. The American neuroscientist António Damásio (born 1944) defines feelings and emotions primarily cognitively and as physical states: "In summary, it can be stated that feelings are made up of a mental evaluation process, which can be simple or complex, and dispositional reactions to this process" (...). - "In my opinion, the essence of feeling lies in numerous changes in body conditions that are caused in innumerable organs by nerve endings."

In the present, the situation with regard to the concept of feeling and emotion is rather confusing: Numerous approaches try to determine the character and regularities of feeling, but without reaching an agreement. B. Marañón (1924), Walter Cannon (1927), Woodworth (1938), Schlosberg (1954), Schachter and Singer (1962), Valins (1966), Burns and Beier (1973), Graham (1975), Marshall and others. Philip Zimbardo (1979), Rosenthal (1979), Schmidt-Atzert (1981), Lange (1998). The American philosopher Robert C. Solomon stated in view of the variety of interpretations: “What is a feeling? One should assume that science has long since found an answer, but this is not the case, as the extensive psychological specialist literature on the subject shows. "

Antonio Damasio makes a clear distinction between "emotion" and " feeling ". Against the background of modern neurobiology , he defined the two key terms as follows: "Emotions are complex, largely automatic programs for actions designed by evolution. These actions are supplemented by a cognitive program that includes certain thoughts and forms of cognition; the However, the world of emotions consists primarily of processes that take place in our body, from facial expressions and posture to changes in internal organs and the inner milieu. Feelings of emotions, on the other hand, are a composite perception of what is going on in our body and our mind when we have emotions As far as the body is concerned, feelings are not processes themselves, but images of processes; the world of feelings is a world of perceptions that are expressed in the brain maps. "

New approaches that take into account research results from neuroscience as well as artificial intelligence see emotions as “modulators” and try to describe them more precisely.

Delimitations

There is no precise scientific definition for the term “emotion”. On the one hand philosophy and psychology endeavor to use the term, on the other hand the neurosciences . The neurosciences deal with the efferent somatic and vegetative reactions of an organism to emotions, while otherwise the affective aspects are in the foreground, negative or positive states from fear and fear to love and happiness.

In contrast to feeling , emotions as an affect - seen from the acting individual - are mostly directed outwards. In the German-speaking area, the term affect refers to a short-term emotional reaction that often results in a loss of control over one's actions. Despite the arousal, an emotional response retains the substance of a course of action .

Compared to moods , emotions are relatively short and intense in time. While moods are often based on needs unnoticed , the respective triggers come more into play with emotions. While emotions can relate to people, for example anger or sadness , a mood can completely lack reference to people, as in the case of melancholy .

Feelings, emotions and moods are equally a part of interpersonal communication , but also non-verbal communication . In perceiving they accompany the cognition , e.g. B. in feeling an evidence . Even intuition , which is initially lacking steps in cognition, is essentially based on a feeling or emotional apprehension.

to form

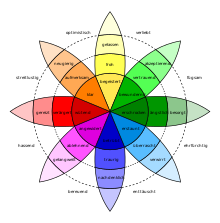

The theory of emotion deals with the catalog of forms . In general, emotions refer to the basic feeling that defines the essence of every human existence . Paul Ekman , who developed a facial action coding system for recognizing emotions on the basis of facial expressions, has empirically proven seven basic emotions: joy , anger, disgust , fear , contempt , sadness and surprise . The basic feeling still includes love , hate and trust .

According to Carroll E. Izard, there are ten forms of emotions that occur in every culture : interest , suffering , aversion , joy, anger , surprise, shame , fear, contempt, and guilt .

Older theories divide emotions into four main groups: fear and despair , anger and anger, joy, sadness . Other forms are disappointment , pity , sympathy , envy , pride and being in love .

development

According to Hellgard Rauh, emotions develop from three courses that can already be observed in infants: pleasure and joy, anxiety and fear, anger and anger.

The differentiations that develop in the course of early childhood can be classified into eight levels:

- absolute stimulus barrier (1st month),

- Turning to the environment (2nd - 3rd month),

- Enjoyment of successful assimilation (3rd - 5th month),

- active participation in social events (6th - 9th month),

- social emotional bond (10th - 12th month),

- practice and research (13th - 18th month),

- Formation of the self (19th - 36th month),

- Games and imagination (from the 36th month).

Emergence

It is believed that the neuronal carriers of emotions are located in phylogenetically older parts of the brain, particularly in the limbic system . With their neural and neuroendocrine processes, they play a key role in species-specific behavior: in Richard Dawkins' theory, sensations such as hunger, cold, worries, aversions, fears, and sexual instincts are understood as genetically determined. In behavioral theories, the expression of emotions is said to be based on inherited innate reactions that were biologically advantageous in evolution and have a signal character towards conspecifics and members of other species.

Current emotions arise in a person on the one hand from the assessment of events (see table: Differentiation of 23 emotions according to the object of the evaluation). On the other hand, emotions can also arise from a restoration of a previous emotional meaning. Sometimes a similar event or a fragmentary memory is sufficient to activate the earlier emotions:

When emotions arise through restoration, a distinction must be made between whether a past event was experienced in a certain context, i.e. whether it is stored in episodic memory . Or whether the reference to an episode can be missing, and fragments can trigger the restoration of emotions: a context is missing and a word may be enough to evoke emotional memories.

|

Event-related emotions and their evaluation in terms of wishes and goals |

Action- related (attribution) emotions to an action or omission by an author |

Relationship emotions towards people or objects |

|||||||

|

Empathy emotions Assessment of an event according to its significance for others |

Expectation emotions Event- related emotions with an expectation of the person |

Wellbeing Emotions d. H. the significance of the event for the person himself, expectations irrelevant |

Criteria are norms and standards and the consequent approving or disapproving |

Appreciation emotions |

Attractiveness emotions |

||||

| hope | Fear / fear | Criteria are the values of the assessed person and their subjective likes / dislikes; contrary to the values, no consensus is assumed for preferences |

|||||||

| he wishes | undesirable | he wishes | undesirable | satisfied | dissatisfied | Own creator |

Other authors |

values | preferences |

|

Sympathetic joy , envy |

Malicious joy , pity |

Expectant event → satisfaction |

Joy , happiness |

Sadness , sorrow |

Pride (approve), shame (disapprove ) |

Approval ( approve ), anger (disapprove ) |

Admiration ( esteem ), contempt ( disdain ) |

Love (like), hate (dislike) |

|

| In the event of an unexpected event or its non-occurrence |

|||||||||

| disappointment | Relief | ||||||||

|

Connection emotions of well-being and attribution emotions (events caused by an originator with meaning for myself) |

|||||||||

| he wishes | undesirable | ||||||||

|

Complacency (self-authors), gratitude (other authors) |

Self-dissatisfaction (self- originators) , anger (other authors) |

||||||||

Components

The life cycle of an emotion is divided into sensory , cognitive , physiological , motivational and expressive components.

In this context, the concept of emotional intelligence also plays a role. Emotional intelligence describes the ability to perceive one's own feelings and the feelings of other people using sensors, to understand them cognitively and to influence them expressively. The concept of emotional intelligence is based on the theory of multiple intelligences by Howard Gardner .

Sensory component

The sensory component is at the beginning of an emotion development. A knowing subject perceives an event (incompletely) through the senses .

Cognitive component

About the cognitive component the knowing subject due to his subjective experiences possible relations between itself and the event recognize .

The knowing subject then makes a subjective assessment of the perception of the event. A subject can - depending on their personal worldview, value system and current physiological state - react to the same event with a different assessment.

The cognitive component is subject to cognitive distortions such as in the interpretation of incomplete sensory information, which is why a “wrong” assessment is quite common.

Physiological component

Depending on the result of the subjective assessment, the subject reacts by releasing certain neurotransmitters and hormones and thus changing its physiological state. This changed state corresponds to experiencing an emotion.

The relationship between physiological and emotional processes is examined by the James-Lange theory , which goes back to William James and Carl Lange , and the Cannon-Bard theory , which goes back to Walter Cannon and Philip Bard . According to the older theory of James and Lange, the physiological changes precede the actual emotion; according to Cannon and Bard, both reactions occur simultaneously as a result of the stimulus.

A research team led by the biomedical scientist Lauri Nummenmaa from the Finnish Aalto University uses 14 body maps to demonstrate the intensity of specific feelings in certain body regions and also that these body maps are surprisingly similar in different cultures.

However, according to the two-factor theory, the physiological reaction depends on the respective situation and its cognitive evaluation. A certain reaction cannot always be assigned to an emotion. For example, rapid palpitation of the heart when jogging is a result of the exertion, while rapid palpitation of the heart with emotions such as anger and fear results from the respective evaluation of the perception. The intensity of the emotion, however, is interdependent to the strength of the physiological stimulus (e.g. physical exertion increases anger; conversely, anger prepares for physical exertion).

After the appraisal theory of Richard Lazarus creates an emotion only when an environmental stimulus is classified initially as relevant (positive or dangerous) or irrelevant and then in a second step, the personal coping strategies (see Coping ) be assessed. This also includes the question of who or what triggered the stimulus. According to these two models, the emotion only arises through a cognitive evaluation. However, it is disputed whether - as Lazarus assumes - an emotion can also be triggered without physiological stimulation. A detailed description of this model can be found in the chapter "Stress models".

Motivational component

The motivational component follows the evaluation of the event and is modulated by the current physiological (or emotional) state. The motivation for a specific action of a person is based on an actual-target comparison, as well as the prediction of the impact of conceivable actions. For example, the emotion anger can result both in the motivation to attack (e.g. in the case of an allegedly inferior opponent) and in the motivation to flee (e.g. in the case of a supposedly superior opponent).

An action can stem from the intention to maintain or even increase the experience of a positive emotion (e.g. joy, love) or to dampen the experience of a negative emotion (e.g. anger, disgust, sadness, fear). A motive for an action only exists if the subject expects the action to improve his or her future (emotional) state.

Expressive component

The expressive component refers to the way an emotion is expressed. This applies above all to non-verbal behavior , such as facial expressions and gestures . Since the research of Paul Ekman it has become known that elementary emotions such as fear, joy or sadness show up independently of the respective culture. These basic emotions are closely linked to neural processes occurring at the same time. Fundamental emotions have a significant relationship to the corresponding facial expression. For example, anger is always associated with lowering and contraction of the eyebrows, slit eyes, and a clenched mouth. This facial expression of anger is universal.

At the same time, the comparative cultural social research comes to the result of a lack of congruence of feeling and the emotion shown. The resulting distinction emphasizes the inwardness of a feeling versus the observable expression of emotions influenced by cultural factors.

Influence of emotions

attention

Emotionally relevant content attracts attention. The connection between attention and emotion is mentioned in many theories of emotion . So led LeDoux in that the processing of some stimuli often occurs without conscious awareness. Particularly frightening stimuli are strongly related to attention. An experiment shows that an angry face is more easily recognized in a crowd of neutral faces than a happy one (face in the crowd effect).

A more recent method of determining the relationship between attention and emotions is the dotprobe task . Participants are shown a neutral word and an emotionally relevant word on a screen. Then a point appears at one of the two places where a word appeared before to which you should react. It turned out that participants react faster when the period appears in the place of the emotionally relevant word. Particularly anxious people draw more attention to the emotionally relevant, often negative stimulus.

memory

Events that are emotionally relevant are particularly deeply imprinted on our memories. Childhood experiences that are associated with strong emotions are more memorable than others. There is a close connection between the amygdala , which is responsible for the emotional evaluation of stimuli, and the hippocampus , which is responsible for our memories. People with damage to the hippocampus are automatically restricted in their emotional and social behavior ( Urbach-Wiethe syndrome ). However, it is unclear whether one tends to remember positive or negative events.

Arousal is an important element of memory. Arousal goes hand in hand with emotions. Strong excitement leads to a short-term deterioration in memory performance, but in the long term to an improvement. When processing strong emotional excitement, hormones and neurotransmitters such as adrenaline, which influence the transmission of signals between nerve cells, are important.

Content that matches the personal, momentary emotion in terms of its meaning is more likely to be remembered than neutral content (mood congruence). Similarly, the concept of state learning is that it is easier to remember content when it is accessed in the emotional state that was present when it was learned. These two phenomena can be explained with the network theory of memory: emotions are connected to memory and knowledge content as nodes in a network. If an emotion is activated, the other nodes are also activated automatically, making access to this content easier.

Judgments and decisions

Emotions influence the assessment of whether something is positive or negative, useful or threatening. Assessments are more positive when the mood is positive. When you are in a positive mood, positive events are considered more likely. But not only judgments about the environment are more positive, but also judgments that concern the person himself. At the same time, a positive mood often leads to risky decisions, as the risk of a negative outcome is often underestimated.

Emotions are also often understood as information, since emotions often arise from evaluations and on top of that provide information about the result of this evaluation. Emotions lead to selective access to the memory. For example, if you are in a negative mood, it is also very likely that negative content in your own biography is more present than positive content. Judgments or evaluations are thus influenced in such a way that emotions induce preferred access to information in memory. Such evaluations can be based on incorrect attributes. This means that emotions are attributed to wrong causes or to causes that are not relevant to the respective emotion. In cases where multiple pieces of information are involved in making decisions, subjects who are positive will need less information to make a decision. In addition, the decision is made faster than with neutral people.

Solve problem

As in the case of decision-making, positive-minded people need less information to solve problems and take more direct problem-solving paths. They have a wider perspective than negatively minded people and are more creative. Positive-minded people tend to look at the global while negatively-minded people focus on the details. But the other way around, the focus of attention also has an influence on the identification of emotions. Big picture people are more likely to see positive faces in a set of faces, while those who look at the detail can see negative faces more easily.

Appraisal theory

health

The influence of emotions on the brain also has effects on the immune system . One discipline that studies this mind-body interaction is psychoneuroimmunology . Negative people are more susceptible to colds, and surgical wounds are slower to heal in negative people. The psychological explanation for this effect of negative emotions on the immune system is that a lot of energy is required to fight off illness and negative emotions lead to lack of energy and exhaustion. Thus, people who are in a negative mood are more susceptible to illness. Studies show that negative feelings such as anger or pessimism increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases over the long term. However, suppressing these feelings increases the risk even more. Emotions also have a major impact on mood disorders such as depression . The impairment of emotions is one of many causes of the disorder here. Studies have also confirmed that the risk of dying from a heart attack is more than twice as great in depressed people as in people without depression. Researchers suspect that negative feelings lead to persistent inflammation and that clinical pictures such as heart disease and depression result from this.

Applications of emotion research

Emotion plays a prominent role in many applied areas. The term emotion regulation (or affect regulation) generally describes all processes that serve the mental processing of emotional states (e.g. "impulse control", "desensitization"). In mental disorders , emotional or affective symptoms are often the central problem. In psychotherapy , emotions are important for the long-term change in experience and behavior.

The psychology of advertising and sales psychology try manipulative produce especially positive emotions associated with the advertised products to provide a better assessment to achieve by the customer. In general, the targeted evocation of emotions is a means of changing the experience and behavior of people and animals. Conversely, emotional manipulation can be strongly influenced and even prevented by intensive psychological and physical training.

The "rationalization" of emotions

Since Richard Lazarus' appraisal theory, emotion research has been on the way to rationalizing emotions. While these used to be considered dangerous and irrational, today they are considered useful and reliable guides, such as: B. shows the widespread use of the term "emotional intelligence". The social historian Joanna Bourke and the philosopher Martin Hartmann warn against such an “overrationalization” of emotions. These were rehabilitated by the emotional turn , which had started against the dominance of the rule of rationality, but by a paradoxical turn in which precisely the rational elements of emotions were emphasized. Rüdiger Schnell argues that the fact that emotions are accompanied by cognitions is confused with the assumption that they are always rational. "Rational emotions" are the expected, understandable emotions in contrast to irrational, incomprehensible feelings.

Emotion management through media and politics

Politics and the media are more about avoiding negative emotions and fears or taking up and redirecting them, or reinforcing positive emotions (“emotion management”). The concept of emotion management is not - as is often assumed - a new coinage from 2018 by Eva Glawischnig , but was used earlier in relation to the media industry, especially for the strategies of tabloids to increase circulation, as well as for emotion-based strategies of populist politics.

An even more targeted management of emotions is required in connection with the rise of the populist parties. The Swiss political and media scientist Lukas Goldner sees the need for the established press to manage discussions on social media more intensely, which could strengthen confidence in the reliability of their information policy. Emotions have a bad rap, and anger is actually the most common emotion expressed on social media. The discussion in Switzerland is “ shaped by the normative demands of Jürgen Habermas and his demands on arguments and the exchange of arguments. With the idea of a domination-free discourse, Habermas also blocked out emotions at the same time. ”By managing emotions in social media, which address people more directly and emotionally than traditional media, attention can now be directed and mobilized in a targeted manner in the face of an increasingly emotionalized audience be, for example, in the direction of more participation . Such media education promotes enlightened decisions: Emotion management on social media serves "as a catalyst and promotes the consumption of established media brands for in-depth information procurement".

Since around 2015, the management of fears has been the focus of emotion management in the media and politics. The catchphrase “taking people's fears seriously” has been in the political semantics of Germany at least since the Fukushima nuclear disaster and the refugee crisis in Europe from 2015 , but also in Switzerland - there, for example, in relation to fears of globalization or the construction of minarets - and Austria - with a view to the emptying of rural areas - has become the standard topos of politics.

Political demands were already articulated in emotional categories earlier, as in the anti-nuclear, rearmament and ecology debates of the 1960s to 1990s. At that time, politicians tried, in some cases with success, to avoid fears or at least panic through strategies of “normalizing” the risks (e.g. by avoiding the presentation of the consequences of higher ionizing radiation doses and emphasizing civil protection efforts ). Niklas Luhmann pointed out that the communication of fears ("fear communication") has a contagious effect insofar as it not only triggers (individual) fear, but can also lead to a systematic formation in the communication system that can no longer be suppressed and spreads. Accordingly, the risks of many people have long been discussed by politics and their fears have been delegitimized.

While the critics defended their fears as real fear, politicians often resorted to psychiatric categories and spoke of the critics' “fear neurosis” in order to avoid communication about the risks and material problems. That made z. B. Peter Hintze at the CDU party congress in 1993, while in Dirk Fischer's speech at this party congress the topos of serious fears emerged - at that time based on the increasing fear of pensioners about burglary.

Today the normalization strategies of risks and the associated delegitimization strategies of emotions have proven to be largely ineffective. For example, politics could not really answer the "annoying questions about the costs of the final storage of nuclear waste, about the botching of the operating companies, about the incidents swept under the carpet"; she “doesn't want to talk about how the risk costs are nationalized and the profits privatized. In view of the extent of the Japanese catastrophe at Fukushima, even “cold” questions about the tangling of the nuclear industry and politics in Japan are completely tasteless ”. Instead, politicians talk about “fears that sound empathetic”, but represent “ paternalistic management of emotions”. For the strategy to work, it needs “citizens who have got used to articulating their political demands in emotional categories” such as the Swiss “minaret phobics”. The left in particular fell into a trap with stirring up emotions, "which they had helped to create: the transformation of politics into social work and from citizens into clients who have to be picked up where they are". Emotionally. "

The forms of emotion management by the press and politics themselves followed the logic of populism , which Eva Glawischnig , the former federal chairwoman of the Austrian Greens, self-critically admits with regard to their politics.

Tom Strohschneider points out that talking about a coming crisis at an early stage (as has been the case since autumn 2018) is a form of emotion management that "everyone can use to make their own soup": from investment advisers to business demands for tax cuts to "distribution brakemen" and the left that sees impoverishment coming. The excess of warning “could set in motion a herd instinct of pessimism, which will then accelerate the crisis”, although the left should in no way benefit from it.

An example of linking politics to diffuse-positive emotions is the rediscovery of the term “ home ”, which has found its way into the names of German federal and state ministries and as a political catchphrase in the discussion. According to the romanticism specialist Susanne Scharnowski , a term that actually has a positive connotation is “managed as a neo-realistic bubble of emotions”, although it remains unclear which problems should really be tackled with the renaming of the ministry. The political semantics, which are increasingly riddled with feel-good adjectives, are to be included in this variant of emotion management, as is the case with the “Gute-KiTa-Gesetz” (official: “Law for the further development of quality and participation in child day care”), Law "(officially:" Law for the targeted strengthening of families and their children through the redesign of the child allowance and the improvement of benefits for education and participation (Strong Family Law - StaFamG) ") or the" Patient Data Protection Law "are applicable reached, see also Newspeak .

See also

- Emotional intelligence

- Emotions in economics

- Emotion work

- Emotion recognition

- Emotion regulation

- Evolutionary emotion research

- Feel-as-Information Theory

- Whim

- Drive theory

- conviction

literature

- Claudia Benthien , Anne Fleig, Ingrid Kasten (eds.): Emotionality. On the history of feelings. Böhlau, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-412-08899-4 .

- Luc Ciompi : The emotional foundations of thinking. Draft of a fractal affect logic. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1997.

- Antonio R. Damasio : Descartes' error. Feeling, Thinking and the human brain. List, Berlin 2004.

- Antonio Damasio : Man is himself: body, mind and the emergence of human consciousness . Pantheon Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3-570-55179-0 , chap. 5, p. 121 ff.

- Charles Darwin : The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals . (1872) Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-8218-4188-5 . ( digitized version of the first German edition from 1877 )

- Ulrich Dieter, Mayring Philipp: Psychology of emotions. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-17-018140-8 .

- Andreas Dutschmann: Aggression and conflicts under emotional excitement. DGVT-Verlag, Tübingen 2000.

- Helena Flam : Sociology of Emotions. An introduction. UVK-Verlag, Konstanz 2002, ISBN 978-3-8252-2359-5 .

- Oliver Grau and Andreas Keil (eds.): Mediale Emotionen. To guide feelings through images and sound. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2005.

- Carroll E. Izard: The Emotions of Man. An introduction to the basics of emotion psychology. Translated from English by Barbara Murakami. Beltz, Weinheim / Basel 1981.

- Rainer Maria Kiesow, Martin Korte (ed.): EGB. Emotional law book. Decalogue of feelings. Böhlau, Cologne 2005.

- Nastasja Klothmann: Emotional worlds in the zoo. A story of emotions 1900–1945. Diss. Phil. Hamburg, Bielefeld 2015, ISBN 978-3-8376-3022-0 .

-

Carl Lange : About emotions. Their nature and their influence on physical, especially pathological, life phenomena. A medico-psychological study. Thomas, Leipzig 1887.

- Emphasis: About emotions. University Press, Bremen 2013.

- Ulrich Mees: The structure of emotions. Hogrefe, Göttingen 1991. ISBN 978-3-8017-0429-2

- Ulrich Mees: On the current state of research in emotion psychology - a sketch. In: Rainer Schützeichel (Ed.): Emotions and social theory. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2006, pp. 104–123. ( Full text (pdf))

- Andrew Ortony, GL Clore, Collins: The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1988.

- Ute Osterkamp : Feelings, emotions. In: Historical-Critical Dictionary of Marxism . Vol. 4, Argument-Verlag, Hamburg 1999, Sp. 1329-1347.

- Jürgen H. Otto, Harald Euler , Heinz Mandl : Emotional Psychology. A manual. Beltz, Weinheim 2000.

- Rainer Schützeichel (Ed.): Emotions and social theory. Disciplinary approaches. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2006.

- Monika Schwarz-Friesel : Language and Emotion. UTB, Stuttgart 2007.

- Karin Schweizer, Klaus-Martin Klein: Media and Emotion. In: Bernad Batinic , Markus Appel (Hrsg.): Medienpsychologie. Springer, Heidelberg 2008, pp. 149-175.

- Robert C. Solomon: Feelings and the Purpose of Life. Two thousand and one, Frankfurt am Main 2000.

- Baruch Spinoza : De origine et natura affectuum. About the origin and nature of affects. The third book. In: Ethica, ordine geometrico demonstrata . Ethics, represented by the geometrical method. 1677. Reissued after translation by Johann Hermann von Kirchmann. Phaidon, Essen (around 1995), ISBN 3-88851-193-3 .

- Ingrid Vendrell Ferran : The emotions. Feelings in realistic phenomenology. Academy, Berlin 2008.

- Richard Wollheim . Emotions. A philosophy of feelings. Translated by Dietmar Zimmer. Beck, Munich 2001.

Web links

- Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Emotional Psychology (ZPID)

- Jean-Marc Fellous: Models of Emotion . In: Scholarpedia . (English, including references)

- Luiz Pessoa: Cognition and emotion . In: Scholarpedia . (English, including references)

- Specialized Sign Lexicon Psychology: Emotion and Signs.

- Marietta Meier, Daniela Saxer: The pragmatics of emotions in the 19th and 20th centuries. In: Traverse 14/2 (2007).

- Nina Verheyen: History of Emotions , in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte , June 18, 2010

Individual evidence

- ↑ Antonio Damasio : Man is himself: body, mind and the emergence of human consciousness . Pantheon Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3-570-55179-0 , p. 122.

- ↑ Bas Kast: How the stomach helps the head to think , Frankfurt am Main 2007.

- ↑ Burkhard wing: The Ent-Negativierung of humans: The psycho-logic of feeling, thinking and needing . Herzogenaurach 2015, ISBN 978-3-00-049954-8 .

- ^ Wilhelm Karl Arnold , Hans Jürgen Eysenck , Richard Meili : Lexicon of Psychology. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau / Basel 1971, Lemma Emotionality.

- ↑ Duden: The dictionary of origin. Etymology of the German language. Mannheim 2007, Lemma Emotion.

- ↑ Hadumod Bußmann (ed.) With the assistance of Hartmut Lauffer: Lexikon der Sprachwissenschaft. 4th, revised and bibliographically supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-520-45204-7 , Lemma Emotive.

- ↑ Ansgar Feist: Continuous recording of subjective and physiological emotion variables during media reception. (No longer available online.) 1999, archived from the original on January 13, 2009 ; Retrieved December 28, 2008 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Robert C. Solomon: Emotions and the Meaning of Life , Frankfurt am Main 2000, p. 109.

- ↑ Antonio Damasio : Man is himself: body, mind and the emergence of human consciousness . Pantheon Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3-570-55179-0 , p. 122.

- ↑ Paul Ekman (ed.): Facial expression and feeling. 20 years of research by Paul Ekman. Paderborn 1988.

- ↑ JH Otto, Harald A. Euler, Heinz Mandl: Emotionspsychologie. A manual. Beltz, Weinheim 2000.

- ↑ Carroll E. Izard: The emotions of the people. An introduction to the basics of emotion psychology. Translated from English by Barbara Murakami. Beltz, Weinheim / Basel 1981.

- ^ Rauh, Hellgard: Prenatal Development and Early Childhood. In: Rolf Oerter and Leo Montada: Developmental Psychology. Beltz, Weinheim 2002, pp. 186f.

- ↑ Ulrich Mees (ed.): Psychology of anger. Hogrefe, Göttingen / Toronto / Zurich 1992.

- ↑ Andrew Ortony, GL Clore, Collins: The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1988.

- ↑ Mees, U .: The structure of emotions. Hogrefe, Göttingen 1991.

- ↑ a b Ulrich Mees: On the current state of research in emotion psychology - a sketch. In: Rainer Schützeichel (Ed.): Emotions and social theory. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2006, pp. 104–123.

- ↑ Lauri Nummenmaa, Enrico Glerean, Riitta Hari , and Jari K. Hietanen: Bodily maps of emotions. PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences), Washington 2013; Published December 30, 2013 before printing; Original articles and graphics , accessed October 15, 2016.

- ↑ Paul Ekman: Reading Feelings. How to recognize emotions and interpret them correctly. Spectrum, Munich 2004.

- ↑ a b David G. Myers: Psychology . 3. Edition. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2014, ISBN 978-3-642-40781-9 .

- ^ A. Öhman, D. Lundqvist, F. Esteves: The face in the crowd revisited: A threat advantage with schematic stimuli . In: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . 80th edition. 2001, ISSN 0022-3514 , p. 381-396 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g V. Brandstätter et al .: Motivation and Emotion General Psychology for Bachelor's . Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-30149-0 .

- ^ Siebert M., Markowitsch H., Bartel P .: Amygdala, affect and cognition: evidence from 10 patients with Urbach-Wiethe disease . In: Brain . 2003, ISSN 0006-8950 , p. 2627-2637 .

- ^ Joanna Bourke: Fear: A Cultural History. Counterpoint 2006.

- ↑ Martin Hartmann: Possibilities and limits of neurophysiological research on feeling from a philosophical point of view. In: K. Herding, A. Krause-Wahl (Hrsg.): How feelings get expression: emotions in close vision. 2nd edition, Taunusstein 2008, pp. 53-64.

- ↑ Rüdiger Schnell: Do feelings have a story ?: Aporias of a history of emotions. Göttingen 2015, p. 146 ff.

- ↑ www.pressreader.com , November 24, 2018.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Ute Scheub: From the meaning of the victim (PDF), broadcast by Deutschlandfunk on April 6, 2007.

- ↑ See e.g. B. A short memory in boom times. Interview with Daniel Zuberbühler, in: handelzeitung.ch, October 28, 2008.

- ↑ Lukas Golder: How emotions create meaning in politics and promote participation. In: www.defacto.expert, November 25, 2016.

- ↑ Take people's fears seriously. In: www.cducsu.de, December 6, 2015.

- ↑ Federal Presidium: Leuthard: Strengthening nationalism is bad for Switzerland. In: www.blick.ch, October 7, 2018.

- ↑ FPÖ-Angerer: Take people's worries seriously and support rural areas! In: www.ots.at, July 25, 2017.

- ↑ Falko Schmieder: Communication. In: Lars Koch: Angst: An interdisciplinary manual. Springer, 2013, p. 202.

- ↑ Niklas Luhmann: Ecological communication. 1986, p. 240 ff.

- ^ 4th party congress of the CDU in Germany. Protocol. 12-14 September 1993 Berlin on www.kas.de.

- ↑ Peter Schneider: Is "feeling" useful as an argument? In: www.tagesanzeiger.ch, April 6, 2011.

- ↑ The child prodigy and the fictional character. In: www.diepresse.com, November 16, 2018.

- ↑ Tom Strohschneider: Crisis as a stove , in www.freitag.de, 47/2018.

- ↑ Sabine Seifert: Researcher on the controversial term: "Rehabilitate home" . In: The daily newspaper: taz . November 19, 2019, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed July 20, 2020]).

- ↑ Home concept in cultural history: The great misunderstanding. A conversation with Susanne Scharnowski (FU Berlin). In: www.deutschlandfunk.de, October 6, 2019.