Fremskrittspartiet

| Fremskrittspartiet Framstegspartiet Progress Party |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Party leader | Siv Jensen |

| Secretary General | Fredrik Färber |

| vice-chairman | 1. Sylvi Listhaug 2. Terje Søviknes |

| founding | 1973 |

| Headquarters | Oslo |

| Youth organization | Fremskrittspartiets Ungdom ( nyn. Framstegspartiets Ungdom) |

| Alignment |

Right-wing populism , national conservatism , economic liberalism |

| Colours) | blue |

| Parliament seats |

27/169 |

| Number of members | 17,968 (2018) |

| Website | www.frp.no |

The Fremskrittspartiet (abbr. FrP ; Nynorsk Framstegspartiet ; German Progress Party ) is a political party of right-wing in Norway , which describes itself as "liberal People's Party".

Assessment by party research

Some political scientists compare the Progress Party with right-wing populist parties such as the FPÖ and the Dutch Lijst Pim Fortuyn , other researchers do not consider such comparisons to be meaningful. For a long time, the party largely distanced itself from other right-wing populist parties, such as the Swedish Sverigedemokraterna . Before the parliamentary elections in Sweden in 2018 , however, some politicians from the FrP expressed an interest in working more closely with the Swedes, who are classified as further to the right, in the future.

In its beginnings, the FrP, founded in 1973, is a right-wing protest party . Although the party was the second largest group in Storting after the parliamentary elections in 2005 , some social scientists still consider the designation as a protest party to be justified; it is not rejected by the party itself. In the course of a comparative analysis of right-wing parties in Europe, the FRP was classified as “moderately nationalist and xenophobic ” and as “more in line with the system”, despite a wing of “ neo-racist populists” . Some social scientists describe this orientation as “right-wing extremism light”. In general, the literature describes the Progress Party as right-wing populist, but compared to the other European right-wing populist parties, the Progress Party can neither be described as radical, extreme nor all-right. Some social scientists have stopped calling the party right-wing populist since the 2013 Storting election. According to them, the Fremskrittspartiet since 2013 has been more comparable to its coalition partner conservatives .

In the store norske leksikon , the party's orientation is described as a mixture of right-wing populism and more traditional economic liberalism.

Program

The party pursues a liberal economic policy and a conservative value policy and advocates a tightening of immigration policy. Further program items are:

- Reduce bureaucracy and simplify the Norwegian tax system

- Tax cuts, financed by saving less income from the state oil business

- Privatization of state companies

- Foreign and security policy partnership with states of the democratic-western canon of values (especially USA and EU); in the work program, the existence of the State is Israel says

- Commitment to the "Christian-Western tradition" and the "cultural heritage rooted in the Christian worldview"

- Privatization of the education system and introduction of an education voucher model

- Independence of the Norwegian Central Bank from political influence

history

At the beginning of the 1970s there was a turning point in the party system in Norway. New political parties emerged through splits and the founding of new ones, one of which was the Fremskrittspartiet. Originally the party was called ALP ( Anders Langes parti til sterk nedsettelse av skatter, avgifter og offentlige inngrep , German Anders Langes party for a strong reduction of taxes, levies and state regulations). Its founder Anders Lange turned against the social democratic welfare state , the Keynesian economic policy and the alleged lack of resistance of the conservatives against this policy. A former South African agent alleged that the party was initially financially supported by South Africa's apartheid regime . After Anders Lange's death in 1974, the party was given its current name for the next election in 1977.

While the founding phase of the party was mainly characterized by its character as a protest party , the Progress Party increasingly included xenophobic slogans in its program in the 1980s. The term “organized racism” was coined on this phenomenon, in contrast to the conventional term right-wing extremism, which some observers believe is unsuitable here. By raising fears of Norway being “flooded” with migrants, the party was intended to further strengthen existing prejudices in the population and to arouse fears of social degradation. At the local elections in 1987, the FrP managed to double its previous mandates. This success was mainly based on the exploitation of racist prejudice against immigrants. The shock of this xenophobic election victory led the Norwegian King Olav V to call for more tolerance towards the “new compatriots”.

In 1994 the party split, with younger, more liberal members leaving the party.

In the elections to the Storting , the Norwegian parliament, the FrP achieved 14.6% of the vote in 2001 and, according to surveys in 2002, was even on the way to becoming the strongest party in Norway. The center-right minority government under Kjell Magne Bondevik relied on the votes of the Progress Party from 2001 to 2005, whereby its chairman Carl Ivar Hagen gained great influence in Norwegian politics and the public. Nationally minded media therefore also called him "King Carl".

From the Storting election in 2005 , the FrP was the second largest party in the Norwegian parliament for eight years. In the Storting election 2013 , she fell behind the conservative Høyre party to third place. On October 7, 2013, the FrP and the Conservatives reached a coalition agreement. The Solberg government was formed on October 16, 2013, the FrP initially occupied seven of 18 cabinet posts.

Opposition to a women's quota

When the Norwegian Labor Party initiated a campaign to promote women in politics between 1985 and 1989, other parties with the exception of the FrP followed this trend and increased the proportion of women among their candidates and members of parliament. Between 1981 and 1989 the Workers' Party increased the proportion of women from 33% to 51% and in 1989 the Norwegian Parliament increased the proportion of women from 40%. In 1989, on the other hand, 10% of the FrP MPs were women. A majority of the FrP voters were male (1985: 69%; 1989: 65%) and had a traditional understanding of gender roles, according to party research. After the parliamentary elections in 2009, 24.4% of the FrP MPs were female, in 2013 it was 20.7%.

Party leader

- Anders Lange 1973–1974

- Eivind Eckbo 1974–1975 (interim chairman)

- Arve Lønnum 1975–1978

- Carl I. Hagen 1978-2006

- Siv Jensen 2006–

After Hagen's resignation on May 6, 2006, the previous vice-chairman Siv Jensen was elected to the party leadership.

Election results for Storting since its foundation

| Election year | percent | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| 1973 | 5.0 | 4th |

| 1977 | 1.9 | - |

| 1981 | 4.5 | 4th |

| 1985 | 3.7 | 2 |

| 1989 | 13.0 | 22nd |

| 1993 | 6.3 | 10 |

| 1997 | 15.3 | 25th |

| 2001 | 14.6 | 26th |

| 2005 | 22.1 | 38 |

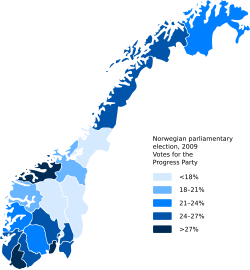

| 2009 | 22.9 | 41 |

| 2013 | 16.3 | 29 |

| 2017 | 15.3 | 28 |

1973 under the name ALP (Anders Langes parti) ; In 2001 two MPs left the group.

literature

- Tor Bjørklund: The Radical Right in Norway: The Development of the Progressive Party . In: Nora Langenbacher, Britta Schellenberg (ed.): EUROPE ON THE "RIGHT" PATH ?. Right-wing extremism and right-wing populism in Europe . Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung , Forum Berlin, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-86872-684-8 , pp. 299–321.

- Kjetil Jakobsen : Revolt of the losers in education? The Progress Party on the Norwegian special route . In: Frank Decker , Bernd Henningsen , Kjetil Jakobsen (eds.): Right-wing populism and right-wing extremism in Europe. The challenge of civil society through old ideologies and new media . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2015, ISBN 978-3-8487-1206-9 , pp. 147-164.

- Anders Ravik Jupskås: The Progress Party: A Fairly Integrated Part of the Norwegian Party System? In: Karsten Grabow , Florian Hartleb (eds.): Exposing the Demagogues. Right-wing and National Populist Parties in Europe. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung / Center for European Studies, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-2-930632-26-1 , pp. 205-236.

- Einhart Lorenz: Right-wing populism in Norway. Carl Ivar Hagen and the Progressive Party . In: Nikolaus Werz (Ed.): Populism: Populists in Übersee und Europa (= Analyzes. Vol. 79). Leske and Budrich, Opladen 2003, ISBN 3-8100-3727-3 , pp. 195-207.

Web links

- Official website ( Norwegian )

- Youth organization website (Norwegian)

- History of the Fremskrittspartiet 1973-2006 ( Memento from January 2, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Anders Lange biography (Norwegian)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Meir gøy på ytre fløy, [1] , accessed on February 11, 2019

- ↑ Fremskrittspartiet: Basic program ( Memento of the original from September 4, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. “The Progressive Party is a liberalist people's party.” (Fremskrittspartiet er et liberalistisk folkeparti) .

- ↑ Frank Decker : When the populists come . In: The time . No. 44/2000.

- ↑ a b Melanie Haas, Oskar Niedermayer , Richard Stöss (eds.): The party systems of West Europe. VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2006, p. 528.

- ^ Economist's Jensen - le Pen comparison 'crude'. January 3, 2014, accessed on January 7, 2016 (English): “Knut Heidar, politics professor at the University of Oslo, said that the comparison with the National Front and other European parties was problematic: It's a result of crude categorization. You put them all in the same bag and think they're all alike. But the Progress Party is more moderate on nearly all points. This is why it's not as controversial in Norway as it is in foreign media. "

- ↑ Forskere: Frp he høyrepopulistisk. September 14, 2013, accessed on July 1, 2016 (Norwegian): “- Yes, de er høyrepopulister. Men sammenlignet med andre slike partier i Europa er de en moderate utgave og har sterkere innslag av liberalkonservative strømninger, sier Jupskås. "(" Yes, they are right-wing populists. But compared to similar parties in Europe, they are a moderate version, and have stronger elements of liberal-conservative currents, Jupskås (Anders Ravik Jupskås, lecturer Department of Political Science, University of Oslo) says. ")"

- ↑ Lars Dønvold-Myhre: Frp-profiler åpner for samarbeid med Sverigedemokratse. July 11, 2018, accessed on February 16, 2019 (nb-NO).

- ^ Dieter Roth: Empirical election research. VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, p. 188.

- ↑ Svein Tore Marthinsen: Tenk om FrP lykkes ( Memento of the original from August 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: Aftenposten . August 14, 2009

- ↑ Publication of the article by Svein Tore Marthinsen on the party's official website ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as broken. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. www.frp.no, 2009, accessed on September 13, 2009

- ↑ Melanie Haas, Oskar Niedermayer , Richard Stöss (eds.): The party systems of Western Europe. VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2006, p. 538.

- ↑ Melanie Haas, Oskar Niedermayer , Richard Stöss (eds.): The party systems of Western Europe. VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2006, pp. 527, 535.

- ↑ Richard Stöss: Right-wing extremism in transition. Berlin 2005, pp. 192, 214.

- ↑ Johan Bjerkem: The Norwegian Progress Party: an established populist party . In: Springer Berlin Heidelberg (Ed.): European View . No. December 15 , 2016, p. 234 .

- ↑ Jenssen, AT (2017). Norsk høyrepopulisme ved veis end? Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift, 34 (03), 230-242.

- ↑ Anders Ravik Jupskås, Olav Garvik: Fremskrittspartiet . In: Store norske leksikon . September 11, 2019 ( snl.no [accessed September 22, 2019]).

- ↑ Policy and work program 2013-2017 (Norwegian). Website of the FrP, accessed on December 16, 2015

- ^ In Norway, the Left Can 'Bribe' Voters with Oil Money . In: Der Spiegel . September 16, 2009. Therein: "the populist Progress Party which campaigned on a platform of tax cuts, privatization and restricting immigration" (ibid.)

- ^ Arthur H. Miller, Ola Listhaug: Political Parties and Confidence in Government: A Comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United States. Pp. 357-386, In: British Journal of Political Science. Vol. 20, No. 3 (July 1990), p. 364.

- ↑ Eschel M. Rhoodie : The Real Information Scandal . Atlanta / Pretoria 1983.

- ↑ Gabrielle Nandlinger: Right-Wing Extremism as an International Problem - The Situation in the Western European States. S. 144–154, In: Kurt Bodewig , Rainer Hesels, Dieter Mahlberg (eds.): The creeping danger - right-wing extremism today. Essen 1990, p. 153.

- ^ Dennis L. Thomson: Comparative Policy Towards Cultural Isolationists in Canada and Norway. Pp. 433–449, In: International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique. Vol. 13, No. 4, Resolving Ethnic Conflicts. La solution des conflits ethniques (October 1992), p. 439.

- ^ The most important course changes of a government Solberg (Norwegian) aftenposten.no, October 7, 2013

- ↑ Richard E. Matland: Institutional Variables Affecting Female Representation in National Legislatures: The Case of Norway. Pp. 737-755 In: The Journal of Politics. Vol. 55, No. 3 (August 1993), pp. 749, 750.

- ↑ http://www.ssb.no/histstat/tabeller/25-3.html

- ↑ http://www.ssb.no/histstat/tabeller/25-4.html