History of Nicaragua

The State history of Nicaragua begins with the independence of between Pacific and Caribbean country situated Nicaragua 1838. The independence from the Spanish colonial power later Nicaragua had already achieved in 1821, first as part of the Empire Mexico , from 1823 as part of the Central American Confederation . The submission to the Spanish colonial power had lasted 300 years for most of the country and began with the extensive extermination of the Indian population of the time. In contrast, the Nicaraguan Caribbean coast had been under British influence for 200 years ( Miskito coast ). In the 170 years that followed independence, the country was a plaything for foreign powers on several occasions. It survived two military interventions by the USA in 1909–1925 and 1926–1933 , at times complete dependence on US companies, a successful revolution in the 1970s and an externally sponsored civil war in the 1980s . Since the 1990s there have been several peaceful transfers of power under democratic conditions.

Indian cultures before Columbus

Presumably, today's Nicaragua was settled by people 6,000 years ago. Before the arrival of the Spaniards in the early 16th century, three large ethnic groups lived in the area of today's Nicaragua, the Niquirano , the Chorotega and the Chontal , who had cultural and linguistic ties to the peoples of northern Mexico. Eastern Nicaragua, the Caribbean coast, was much less populated by people who had immigrated from Colombia and Panama .

The area between Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific was inhabited by the Niquirano, who were ruled by a King Nicarao at the time of the Spanish conquest . Some consider it to be Nicaragua's namesake, another hypothesis derives it from the Nahuatl (nican = "here", aráhuac = "people").

Colonial times

“Discovery” and conquest by the Spaniards

On his fourth voyage, Christopher Columbus reached the coast of Nicaragua in 1502 and followed it from the mouth of the Río Coco , the Cabo Gracias a Dios . He anchored at the mouth of the Río San Juan to withstand heavy storms.

In 1519 the conquistador Pedrarias Dávila made raids from Panama to Costa Rica and Nicaragua. With Granada in 1523, León in 1524 and Bruselas - the latter deserted again after a few years - the first Spanish colonial cities were founded in Nicaragua near the Pacific coast, settled by Spain as a colony in the 1520s , in order to achieve the encomienda , the distribution of large estates to the conquistadors, to set in motion. Because although the immediate booty of the conquest to Nicaragua was relatively high, it became clear in its course that the wealth lies in the people. While the Kazike Nicarao had his land requisitioned for the Castilian king, converted to Christianity and given valuable gifts, the Kazike Diriangén lulled the Spaniards with his baptism in order to then attack them on the battlefield with several thousand indigenous people.

Any resistance to submission was viewed by the conquistadors as a rebellion, which was in principle answered with war and enslavement. The economically and culturally highly developed peoples of the Mangues , Pipil , Nicarao and Choroteguas were abducted and enslaved, Nicaragua was depopulated. The monk Bartolomé de Las Casas wrote in 1552: "In the whole of Nicaragua today there should be 4,000 to 5,000 inhabitants; it used to be one of the most densely populated provinces in the world".

Cortés' captain Pedro de Alvarado conquered Guatemala and El Salvador from 1523 to 1535 . In 1524 they reached San Salvador . The two domains of Cortés on the one hand and Pedrarías on the other hand collided in the Nicaragua / Honduras region. Gil González Dávila and Andrés Niño conquered Honduras in 1524. When the Capitán Dávila, sent by Pedrarías, landed on the Caribbean coast with his own capitulación acquired in Spain , he was sent back to Spain in chains by Cortés' people. Since governors were installed directly by the Spanish crown because of the indigenous resistance in Honduras and Panama, Nicaragua was left to Pedrarías. A significant part of the population of today's Nicaragua was enslaved in 1538 and deported to the silver mines of Peru and Bolivia.

In 1539, Diego Machuca discovered the Río San Juan as a waterway between the Caribbean and Lake Nicaragua . In 1551, the Spanish chronicler Francisco López de Gómara said: “You only have to make a firm decision to make the passage and it can be carried out. As soon as there is no lack of will, there will also be no lack of funds ”. But the Spanish King Philip II saw God's creation in the land bridge between the two seas, which man is not entitled to improve. Therefore, the plan for an interoceanic Nicaragua Canal has not been pursued for the time being.

British rule on the Miskito Coast

For a long time, Spanish colonial rule was limited to the Pacific coast and its hinterland on Lake Nicaragua and the smaller Lake Managua . The Caribbean coast ( Miskito coast ), which was separated from the rest of the country by mountainous and impassable regions and was inhabited by the Miskito Indígenas, came under the influence of the British colonial empire for a long time from Jamaica with the territory of today's Belize . In the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty of 1850, the United Kingdom and the United States pledged not to colonize or occupy any part of Central America and gave each other the exclusive right to build a planned Nicaragua Canal . When the United Kingdom ceded its protectorate to Honduras in 1859, it met with resistance from the indigenous population. On January 28, 1860, the United Kingdom formally ceded the Miskito Coast from Cabo Gracias a Dios to Greytown to the sovereignty of Nicaragua in the Treaty of Managua . In it, the Miskito were also assured of internal autonomy. The chief of the Miskito accepted the change in circumstances, which limited his authority to local affairs, in return for an annual allowance of £ 1,000 until 1870.

Anti-colonial resistance in the 18th century

In 1725 an uprising of the indigenous people against the Spaniards broke out in León. In 1777 the Boaco Indígenas rose against the Spaniards under the leadership of their cacique Yarince . Popular uprisings as a result of the French Revolution and Napoléon I's occupation of Spain culminated in the beginning of the War of Independence in the entire Pacific region of Central and South America in 1811/12, and the first demands for the removal of the Spanish governor from office were made.

Independence from Spain

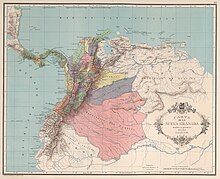

On September 15, 1821, the viceroyalty of Guatemala, to which Nicaragua belonged, proclaimed its independence from the Spanish crown. The Jacobin cap of the French Revolution still adorns his flag over the five volcanoes of the country. First part of the Mexican Empire , two years later it became the United Provinces of Central America, from which the Central American Federation emerged , which included Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Costa Rica and El Salvador. The eastern part of what would later become Nicaragua, the British Miskito Coast , was claimed by the short-lived Republic of New Granada.

independence

In 1838 the state of Nicaragua declared its independence and thus initiated the dissolution of the Central American Confederation .

Inner conflicts and Walker's rule

The contrasts between the liberal elite from León and the conservative elite from Granada shaped the politics of the young country. When the differences within the Nicaraguan oligarchy turned into civil war in 1856 , the “liberals” called on the North American adventurer William Walker with a small private army against their conservative opponents. However, Walker strove for the submission of all of Central America, proclaimed himself President of Nicaragua, and reintroduced slavery , which was abolished in 1824 . It was not until 1857 that he was defeated by the United Army of Central American States and fled.

Disregard for state sovereignty and indigenous uprising

In the nineteenth century the United States and European powers showed how little they valued the sovereignty of the state; Walker's rule, evidently the result of the illegal seizure of power by a foreign mercenary force, was directly recognized by the United States. In 1854 the arrest of one of its citizens prompted the United States to bomb the Nicaraguan town of Greytown . Despite international protests, US President Franklin Pierce defended the bombing by pointing out that the city was a "pirate's nest".

In 1878, after an attack on the consul in León, the so-called Eisenstuck affair , the German Empire successfully intervened militarily in Nicaragua. At the end of April 1895, 400 British soldiers occupied the customs house in Corinto port to enforce demands by the British government regarding some British citizens deported from Nicaragua.

Starting in the city of Matagalpa , there was an uprising of the indigenous population in the Pacific region in 1881. The trigger was the privatization of the previously common property, as a result of which they were forced into wage or forced labor, mostly on the expanding coffee plantations.

Rule of the "liberals" and incorporation of the Miskito coast

With the regime of General José Santos Zelaya in 1893, the economically important coffee oligarchy of the "liberals" came to power. Zelaya enforced the separation of church and state and centralized control of the whole country, promoted the cultivation of coffee and had the traffic routes expanded. With the decree of the reintegration of the Miskito coast in 1894, his government had the Miskito coast militarily occupied by General Cabezas after 14 years of complete autonomy , although the self-determination of the Miskito within the Nicaraguan Republic was reaffirmed in an arbitration award by King Franz Joseph I in 1881 , after the king of the Miskitos had already refused in 1864 to recognize the limitation of his authority by Nicaragua. After the occupation, the Miskitos were promised the maintenance of a number of tax privileges, and trade and exploitation of natural resources should be subject to the misgovernment. The Nicaraguan Department of Zelaya emerged from the Miskito coast . North American companies began to plant extensive banana plantations on the Miskito Coast in 1882. By the turn of the century, they managed to gain control of almost all of the area's trade. A military rebellion on the Caribbean coast and US pressure forced General Zelaya to resign in 1909.

Military occupation of Nicaragua by the USA 1912–1933

In 1909 the US supported an uprising against President Zelaya by General Juan José Estrada , governor on the Miskito Coast. The US sent warships to the coast and US mercenaries supported Estrada, who soon became president. In 1911 Estrada resigned in favor of Adolfo Díaz . The new Conservative President Díaz, until his election the accountant of a North American mining company in Nicaragua, took out millions in loans from US banks in 1911 and, as security, left the US government with direct control of the Nicaraguan customs revenue. A year later, the Díaz government had to be rescued from an insurgent army of the previous Minister of War Luís Mena by US marines, who landed in Nicaragua on August 14, 1912 and occupied the cities of Managua, Granada and León. In advance, the Americans had asked Díaz to guarantee the safety of American citizens and their property in Nicaragua during the uprising. Díaz replied that he was unable to do so; "As a consequence of this, my administration wishes that the United States government and its security forces guarantee the security of the property of American citizens and that they extend their protection to all residents of the republic." US Marines then occupied Nicaragua from 1912 to 1933 Except for a nine month period beginning in 1925. During this time, the Marines mostly supported the conservative government against liberal rebels, for example in the Guerra Constitucionalista , the war between two political camps for the presidency.

Rise of the Somozas

In 1927 civil war flared up again between the conservative government and the liberals, whose generals included Augusto César Sandino . After the personal envoy of the US President Calvin Coolidge had promised the leader of the Liberals, General José María Moncada, the presidency, he enforced the Espino Negro Pact , in which the disarmament of the Liberals was codified and which thus effectively ended the Guerra Constitucionalista . Only Sandino and 30 of his soldiers did not allow themselves to be disarmed, but withdrew to the mountains in the north of the country. There Sandino again set up a small force, the Ejército Defensor de la Soberanía Nacional , fought against the government and inflicted a number of serious defeats on the US rangers, who had been stationed in the country since 1927, over the course of six years.

In 1932 and 1933, the United States withdrew its troops after they had set up and trained a Nicaraguan "National Guard" ( Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua ) since 1927 , the command of which they promised their confidante, Anastasio Somoza García . This National Guard, for which there was formally a (actually inactive) conscription, exercised both the army and the police function at the same time. Somoza's uncle-in-law, the liberal Juan Bautista Sacasa , was elected president in a US election . He was inducted into office on January 1, 1933. A day later, the last units of the US Marines left the country. After the US withdrew, Sandino and his troops laid down their arms and entered into a peace agreement with Sacasa on February 2, 1933. Somoza's Guardia Nacional , over which the president had insufficient power, failed to comply with the peace agreements and continued to fight Sandino's troops. A year after the peace agreement, Somoza invited Sandino and his closest officers to a banquet at which they were murdered on February 21, 1934 at his instigation. Sandino himself was shot in the back.

Somoza's presidency

Three years later, Anastasio Somoza García launched a coup against Sacasa and was elected president. Until 1979, the Somoza family never gave up command of the National Guard and established one of the largest economic empires in Latin America. She constantly expanded her influence in the modernizing economy, suppressed civil unrest and initiated the reconstruction of the country, which was destroyed by an earthquake in 1931, in such a way that she was able to increase her property considerably on this occasion. A major fire that destroyed the capital Managua in 1936 also provided the occasion.

Despite his previous sympathies for German and Italian fascists, Anastasio Somoza García immediately sided with the United States during World War II and declared war on Japan on December 9, and Germany and Italy on December 11, 1941. As a result, he took the opportunity to expropriate all Germans in Nicaragua and to take over the majority of their property and their coffee plantations.

President Somoza appointed his younger son, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, in 1946 to command the national guard, which was fully committed to the interests of the family. Border conflicts with Costa Rica in 1948/49 and 1955 and with Honduras in 1957 were overcome with the support of the USA. From February to June 1954, the mercenaries needed by the CIA as part of Operation PBSUCCESS against Guatemala were trained in Nicaragua, including at Somoza's private estate, El Tamarindo. The poet Rigoberto López Pérez murdered President Somoza at a banquet in 1956, after which he himself was shot by Somoza's bodyguards. Somoza's son, Colonel Luís A. Somoza Debayle , became president and held the post until 1963.

The constitutions of 1939, 1948 and 1950 had tied the introduction of women's suffrage to a qualified majority in the legislature. The active and passive right to vote for women was introduced on April 21, 1955. In the elections of 1957, women were allowed to vote for the first time under the same age requirements as men. After the 1979 revolution, all Nicaraguan citizens over the age of 16 were given the right to vote.

While cotton cultivation on the Pacific coast became the country's main source of foreign exchange, US firms gradually withdrew from the Caribbean region. Their banana plantations, the depleted gold and silver mines and the overexploitation of precious woods left deep traces and a huge, deforested primeval forest area in the northeast as a barren steppe. Formerly 933 km of railway network (with a road network of 350 km at that time) of the banana and timber companies fell into disrepair, not least because Somoza gave "earned" officers licenses for bus lines parallel to the railway, who then buy buses from him, the general agent of Mercedes-Benz could. The small remnants of this network that still exist today in poor condition are hardly used any more.

In 1961, an invading army of Cubans in exile and Latin American mercenaries was set up under the direction of the CIA in Puerto Cabezas on the Atlantic coast, which landed in the Bay of Pigs in Cuba and was defeated by the Cuban troops (see Invasion in the Bay of Pigs ).

In 1967, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, until then head of the National Guard, came to the presidency as a candidate of the Liberals through electoral fraud . His methods of government were contrary to liberal principles, but he has enjoyed generous US economic, financial and military aid. After drafting a new constitution with special powers for the president and the interim government of a junta from 1972 to 1974, he was re-elected president.

When a strong earthquake destroyed the capital Managua on December 24, 1972 and claimed around 10,000 lives, the Somoza family used the disaster for their own enrichment: they diverted large parts of the international aid money to their accounts, and donated aid goods were sold by their companies and they seized the construction and banking industry that had flourished as a result of the disaster. Large parts of the city center and the cathedral have not been restored to this day.

Despite the maintenance of a formal multi-party system, any genuine opposition was suppressed by the National Guard, trade unionists harassed, and small farmers driven from their plots of land by the use of force into the deserted areas of the north-east or the remote areas of the south-west with no access to traffic. The opposition conservatives turned out to be inactive and powerless. Her interest was focused solely on the needs of her clientele.

Reign of the Sandinista

Civil war and the Sandinista takeover

Triggered by corruption and state abuse of power by the dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle , violent clashes broke out in 1977, which culminated in a civil war and spread across the whole country. On July 17, 1979, Somoza fled to Florida; on July 19 of that year the victorious guerrillas entered Managua; the Nicaraguan Revolution had triumphed.

His successor in the presidency from 1985 to 1990 was Daniel Ortega .

Successful domestic politics in the first few years

Initially, the Sandinista, as the supporters of the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional , abbreviated FSLN (German: Sandinista National Liberation Front) were called, pursued a peaceful and democratic program; A broad-based education campaign, including among adults, led to a significant reduction in the illiteracy rate, and indigenous and rural art and culture were fostered. An expression of this was the appointment of the world-famous poet and priest Ernesto Cardenal as Minister of Culture. Schools were established across the country, often housed in simple huts; Teachers were trained in crash courses because under Somoza insufficient funds were made available for teacher training. The health system was developed, and here too it was possible to establish hospital wards in the country, which for the first time distributed an at least poor hygiene program.

Another domestic political project was the development of women's rights. This program built on the notoriety of Sandinista heroines - a remarkable process in macho Nicaragua that may have contributed to Violeta Chamorro's later electoral success . But the worldwide success of the books by Gioconda Belli ( Inhabited Woman ) should also be mentioned in this context.

Conflict with the Miskitos

Under the Sandinista rule, 8,500 Miskito Indians were forced to resettle in 1982 . They had to leave the coastal region and were deported inland. About 10,000 Miskito fled to neighboring Honduras.

The contra war

In the 1980s, US President Ronald Reagan attempted to overthrow the Sandinista government, which has been described as communist in much of the Western media. He arranged for the mining of the only Nicaraguan Pacific port of Corinto and the financial and military support of the Contras , paramilitary groups that operated mainly from Honduras and among which were soldiers of the former Somozi National Guard . The money for support came from secret arms sales by the US to Iran (see also Iran-Contra affair ). The Contras tried to destroy the infrastructure , carried out terrorist attacks on the rural population, laid mines, burned the crops and stole cattle in order to destabilize the situation in the country and unsettle the population. Reagan called these groups "freedom fighters". At the same time, the USA stoked clashes between the Sandinista government and the Miskito indigenous people on the Caribbean coast. Nevertheless, the first free elections in Nicaragua in 1984 resulted in confirmation from the Sandinista government. International election observers, including the former American President Jimmy Carter , attested that the process was fair.

The support of the Sandinista revolution by leftist movements in the western world reached its peak in these years, so that at times several hundred mostly young adults volunteered to help with the construction and harvest.

The International Court of Justice in The Hague , which Nicaragua seized in 1984, sentenced the United States on June 27, 1986 to a payment of 2.4 billion US dollars as compensation for the consequences of its military and paramilitary actions in and against Nicaragua ( Nicaragua v. United States of America ). The United States declared the Court of Justice unauthorized to judge the United States. In a resolution, the UN General Assembly called on the USA to comply with the judgment. Only the US, Israel and El Salvador voted against the resolution; the US refused to make the payment to Nicaragua. Instead, they increased aid to the US-led mercenary army attacking Nicaragua.

In 1988, as a result of the peace negotiations between the Central American states, the Esquipulas II Agreement was signed by the Central American presidents. In this agreement, the presidents agreed on the demobilization of all irregular troops, the downsizing of the regular army and free and secret elections. This political opening eventually led to the democratic elections of 1990, which were monitored by the United Nations with the consent of the Sandinista government. However, Nicaragua, which was still under Sandinista rule, was the only participating state that fulfilled the agreements.

Victory of the Anti-Sandinista and its Causes

In the elections on February 25, 1990, the anti-Scandinavian electoral alliance UNO (Unión Nacional Opositora) surprisingly won with 55.2% of the vote; the Sandinista party, the FSLN (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional), received 40.8%. The UN consisted of 14 conservative and anti-Scandinavian parties; with the support of the USA, it promised peace, prosperity and the end of the US embargo. The UN candidate was the newspaper publisher Violeta Chamorro , widow of the newspaper publisher Pedro Chamorro, who was murdered under Somoza, and a member of the politically influential Chamorro family .

At the time of the election, the war against the US-funded Contra had claimed more than 29,000 deaths; Since 1980 the economic blockade imposed by the USA had paralyzed the development of Nicaragua. The government had tried to save the economy from the collapse by means of a strict austerity policy, which was becoming apparent as a result of the war-related armaments and the economic sanctions of Western countries, especially the USA. In the meantime, inflation had peaked at 3,000 percent a year. Unemployment was high and the standard of living was low. However, great strides have been made in education, health and land reform.

The economic situation, the open threat of the US to continue the boycott and the war, as well as the losses in the population are commonly seen as the reasons for the UN election victory. Although this ended the war and the blockade, western industrialized countries also acted as lenders, but to a far lesser extent than the Nicaraguans wished.

Sandinista corruption of the transition phase

Some Sandinista leadership cadre enriched themselves in the transition phase between February 25, 1990 (election day) and April 25, 1990 (handover) by issuing property titles, privatizing company cars and transferring state assets to private individuals. This enrichment is denoted by the political word piñata . In at least 200 cases, state assets and individual operations were transferred to the party. The FSLN never resolved these cases, which led to a deep crisis of confidence and loss of credibility. In the new government, the moderate forces on both sides cooperated. In the same year, the contra was incorporated into political and constitutional life. However, the situation after the end of the revolution was extremely tense. The radical forces formed, rearmament took place; the disappointed Contras were called Recontras , the disappointed Sandinista Recompas .

Chamorro and Alemán Governments

Two factors played a key role in preventing the situation in Nicaragua from exploding. On the one hand, Violetta Chamorro named Humberto Ortega ( Daniel Ortega's brother ) supreme commander. So she succeeded in bringing the vast Sandinista army under one, albeit Sandinista, control. On the other hand, she was in a continuous weekly dialogue with the Sandinista for months, thus avoiding an armed uprising. In doing so, she certainly benefited from the fact that she was the representative of an influential family that owned almost the entire press (especially La Prensa ).

Among the members of the Chamorro family were both sympathizers of the Sandinista and staunch supporters of the Contra - typical of Nicaraguan society, which, despite bitter armed conflicts, especially during the revolution, cannot be separated into sharply differentiated groups (or parties).

The new government, in which the FSLN held many important posts, decided on a comprehensive stabilization and austerity program: a capitalist private economy was introduced, the currency was devalued, prices for basic food rose, the army was drastically reduced, the state apparatus downsized, social institutions like kindergartens were closed, the health system was privatized, school fees were raised, agricultural reform and nationalization in the economic sector were reversed. Overall, a neoliberal policy has been pursued in Nicaragua since then . While inflation was brought under control and the United States praised Nicaragua for its development , foreign debt, unemployment, illiteracy rates and child mortality rose and life expectancy fell.

Many of the privatizations were carried out during the years of government under Arnoldo Alemán from 1996, who seized the opportunity to increase his fortunes. The promised prosperity stood not only for the returning supporters of Somoza, who had fled to the USA after the 1979 victory, but also for some former Sandinista.

In 1994 four parties left the UN, which was henceforth called APO (Alianza Política Opositora). In 1996, however, the same groups reunited to form the Alianza Liberal, which won the 1996 elections with Arnoldo Alemán as the presidential candidate. Overall, the political system in Nicaragua is characterized by many divisions and new foundations.

Government of Alemán and Corruption

Arnoldo Alemán from the Alianza Liberal (AL) prevailed in the 1996 presidential election . The Alemán government was accused of massive corruption and nepotism. After the end of his term in office in December 2003, Alemán was sentenced to 20 years in prison, which he has not yet had to serve. However, he is under house arrest and is not allowed to leave the Department of Managua.

Together with Daniel Ortega from the FSLN, Alemán promoted the cooperation between their two parties (“el pacto”). This went so far that they tried to create a two-party state through changes to the law and the constitution, by making access to new parties more difficult and by forbidding free lists of citizens. They also had and still have a great influence on the composition of the most important bodies (Supreme Electoral Council, State Audit Office, Supreme Court) in the country. Furthermore, the President and the Vice-President receive parliamentary status for life after their departure. Alemán benefited from the associated immunity in his corruption proceedings.

Bolaños presidency

Despite the success of the Sandinista Party in the local elections in 2000, the FSLN lost again in 2001. Daniel Ortega ran again as a presidential candidate, although many in the party had opposed his candidacy. In the end, the Liberal Conservative Party (PLC) with Enrique Bolaños and 53% of the vote prevailed against 45% of the FSLN. The Sandinista justified their renewed defeat with a campaign of fear that Bolaños waged against Daniel Ortega. Bolaños, supported by the US, portrayed Ortega as a terrorist friend and sowed fear that if the FSLN won, Nicaragua would be isolated and no more aid would be received.

The new president was committed to fighting corruption. He called for the immunity of the former President Alemán to be lifted, as well as an end to the corruption that he had witnessed himself as Vice President under Alemán. Internationally, the USA and the IMF put pressure on and demanded transparency of public funds and the punishment of corruption as a prerequisite for further funds. Bolaños' media anti-corruption campaign was also viewed with suspicion. The government's new privatization plans, in which state goods were once again to be sold at a fraction of their value, suggested new corruption.

In July 2005 the presidents of the states of Central America and Mexico condemned the actions of the left Sandinista to weaken the president. The opposition, which has the majority in parliament, passed a series of laws that should lead to the disempowerment of President Enrique Bolaños.

Renewed Ortega presidency

The candidate of the left, former guerrilla leader and former first head of state after the Sandinista revolution, Daniel Ortega , was able to prevail in the presidential election in 2006 with 38.1% against 30% of the vote against the conservative candidate (Eduardo Montealegre) Years back to power. The election was observed by the EU, the OAS and delegations from other states (with a total of 11,000 election observers). With one exception (the US delegation), the election observers agreed that the election was fair and transparent. The US election observers spoke of "anomalies" which they did not specify. The head of the EU mission, Claudio Fava , said his organization had not found any election fraud or attempts to do so. Overall, the election was calm and uneventful. The Sandinista became Nicaragua's strongest party again. Daniel Ortega has been President of Nicaragua since January 10, 2007.

In a zero hunger program, school children receive a free meal every day. Healthcare and education are free again, and in order to be less dependent on food imports, small and medium-sized farmers and entrepreneurs are offered land and loans at very low interest rates, but are forced to join Ortega's party, the FSLN.

Ortega was re-elected in the 2011 and 2016 presidential elections (see also list of Nicaraguan presidents ). The country remains the second poorest in Latin America, ahead of Haiti , and under Ortega's rule the personalized and authoritarian features of politics have increased again. Ortega's family members took on important positions, popularly even his wife Rosario Murillo , who has been Vice President since 2017, took over command. The decision to build the Nicaragua Canal as a shipping route between the Atlantic and Pacific by a Chinese investor at the end of 2014 is intended to give the country an economic upswing, but it has been criticized for its lack of transparency, concerns about profitability and environmental and social impacts; It is uncertain whether the world's largest infrastructure project with an estimated cost of 50 billion US dollars - a multiple of Nicaraguan GDP - will be implemented in the medium term. Ortega maintains good relations with the socialist ruled countries of Cuba and Venezuela , but at the same time works closely with entrepreneurs and fulfills all international obligations - such as those of the IMF - so that his gradual elimination of the opposition has not sparked international protests. In 2016, the country was ranked 145 out of 176 in the corruption perception index .

Protests against the Ortega government in 2018

In April 2018, President Ortega decided to relieve the social security bill with a five percent cut in pensions, which immediately sparked demonstrations in virtually every city in the country from April 19. The police used live ammunition to hold them down, and nocturnal troublemakers and free shooters also went into action. At least 26 people were killed in April. The students of the state universities, which are considered a domain of the FSLN, also turned against the government. The “People's President” then wanted to negotiate (exclusively) with the country's entrepreneurs, which they refused due to the repression. There were also increasing demonstrations against the corrupt clan surrounding the president. Protests against arbitrary expropriations in the preparation of the Nicaragua Canal followed . The announced social security reform was withdrawn. The regime banned independent television broadcasters from broadcasting during the unrest, and journalists were also among the fatalities. The demonstrations lasted for weeks and resulted in more deaths in the attack by pro-government activists on the universities occupied by protesting students. According to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) , the number of fatalities reached 76 after just under a month . Hundreds of thousands took to the streets in various cities on May 30th and for the first time Ortega took their concerns up when he ruled out his resignation. Again there were deaths, this in the cities of La Trinidad and Masaya . Amnesty International accused the government of using a "shoot to kill" strategy, that is, deliberately accepting the dead.

By mid-June the number of deaths had risen to 180. The Bishops' Conference had proposed early elections as a solution to the crisis and announced that the government had "surprisingly" started an independent investigation to determine who was responsible for the acts of violence. The bishops broke off the talks, however, because Ortega had not kept the important promise of the invitation to international organizations, for which Foreign Minister Denis Moncada cited "bureaucratic" reasons. By June 22, the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights of the OAS stated the number of people killed as over 200. On July 8th alone, 38 people died in Carazo in this one city.

When, according to the OAS, 250 people had already been killed, UN Secretary-General Guterres called for an end to the violence for the first time on July 11 and again a week later. The "disappeared" were not included in these numbers of victims, so the number of those killed was plausibly estimated at around 400. As a matter of urgency, the regime pushed through a new law with which, according to the protest note of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights ( UNHCHR ), "peaceful protest can be punished as terrorism". During the entire period of the popular uprising from April to July, the indigenous district of Monimbó in Masaya was barricaded . According to writer and ex-Sandinista Gioconda Belli , Ortega's wife Rosario Murillo's propaganda was “more Goebbels than Orwell ” (“This is more Goebbels than Orwell”) when she spoke of peace and reconciliation on July 17, 2018 while the police were at the same time and paramilitaries attacked Monimbó with Kalashnikovs , sniper rifles and artillery.

literature

- Jeffrey L. Gould: To die in this way. Nicaraguan Indians and the myth of mestizaje, 1880-1965. Duke University Press, Durham, NC et al. 1998, ISBN 0-8223-2098-3 , ISBN 0-8223-2084-3 .

- Francisco José Barbosa Miranda: Historia militar de Nicaragua. Antes del siglo XVI al XXI. 2nd Edition. Hispamer, Managua 2010, ISBN 978-99924-79-46-9 .

- Frank Niess: The legacy of the Conquista. History of Nicaragua. 2nd Edition. Pahl-Rugenstein, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7609-1297-4 .

- Matthias Schindler: From the Triumph of the Sandinista to a democratic uprising. Nicaragua 1979-2019 , Berlin: Die Buchmacherei, 2019, ISBN 9783982078304

- Jaime Wheelock Román : Raíces indígenas de la lucha anticolonialista en Nicaragua. De Gil González a Joaquín Zavala (1523 a 1881). 7th edition. Siglo XXI Ed., México 1986, ISBN 968-23-0551-9 .

Web links

- Volker Wünderich: Nicaragua: History and State. In: LIPortal. last updated in March 2017.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Nicaragua Encarta ( Memento November 1, 2009 on WebCite )

- ↑ See for the understanding of the ideologies against the specific background of the country Hans Scheulen: Transitions of freedom. The Nicaraguan Revolution and its historical-political scope. DUV, Wiesbaden 1997, especially pp. 131-133.

- ^ Corinto Tariff in Pawn. And Four Hundred Sailors to Land. In: The New York Times . April 26, 1895 (English).

- ↑ Ultimatum to Nicaragua. In: The New York Times . March 28, 1895 (English).

- ↑ José Luis Rocha: The Chronicle of Coffee , 2001 (English); Julie A. Charlip: Cultivating Coffee. The Farmers of Carazo, Nicaragua, 1880-1930. Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 2003, ISBN 0-89680-227-2 ( review ); Elizabeth Dore: Debt Peonage in Granada, Nicaragua, 1870–1930: Labor in a Noncapitalist Transition. In: Hispanic American Historical Review. Volume 83, 2003, No. 3, pp. 521-559.

- ↑ Foreign Relations of the United States 1912, pp. 1032 ff.

- ^ Arthur R. Thompson: Renovating Nicaragua. In: The World's Work: A History of Our Time. Volume 31, 1916, pp. 490-503.

- ↑ Bernard C. Nalty: The United States Marines in Nicaragua. US Marine Corps, Washington 1968 (digitized version) .

- ↑ Don M. Coerver, Linda Biesele: Tangled Destinies. Latin America and the United States. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque 1999, pp. 77 f.

- ^ Antonio Esgueva Gómez: Conflictos y paz en la historia de Nicaragua. In: Instituto de Historia de Nicaragua y Centroamérica (ed.): Talleres de Historia. Cuadernos de apoyo para la docencia. Managua 1999, p. 50.

- ↑ La Gaceta, diario oficial. Volume 45, No. 269 of December 11, 1941 and No. 270 of December 12, 1941.

- ↑ a b Michael Krennerich: Nicaragua. In: Dieter Nohlen (Ed.): Handbook of the election data of Latin America and the Caribbean (= political organization and representation in America. Volume 1). Leske + Budrich, Opladen 1993, ISBN 3-8100-1028-6 , pp. 577-603, pp. 581-582.

- ↑ Christine Pintat: Women's Representation in Parliaments and Political Parties in Europe and North America In: Christine Fauré (Ed.): Political and Historical Encyclopedia of Women: Routledge New York, London, 2003, pp. 481-502, p. 491.

- ^ US dismisses World Court ruling on contras. In: The Guardian. June 27, 1986 (English).

- ↑ Noam Chomsky: "The Evil Scourge of Terrorism": Reality, Construction, Remedy. In: Junge Welt. March 30, 2010.

- ^ Wilhelm Kempf: Voting decision or surrender? In: Das Argument (1990), No. 180, pp. 243-247. queried on February 25, 2010.

- ↑ Carlos Alberto Ampié: If necessary , the Virgin of Guadelupe helps. In: Friday .

- ↑ Hernando Calvo Ospina: Once upon a time in Nicaragua. In: Die Tageszeitung , Le Monde diplomatique , July 16, 2009.

- ↑ ARD Weltspiegel , July 19, 2009.

- ↑ Karsten Bechle: Nicaragua. In: Federal Agency for Civic Education , Dossier Internal Conflicts, November 29, 2015; Ralf Leonhard: Nicaragua. A land of political roller coaster. In: Federal Center for Political Education . January 9, 2008.

- ↑ Nicaragua is drifting towards dictatorship once again. In: The Guardian. August 24, 2016; "Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo are attempting to take absolute control of state institutions"

- ^ Wife and Running Mate: A Real-Life 'House of Cards' in Nicaragua "pushing aside nearly all the members of her husband's inner circle"

- ↑ David Gregosz, Mareike Boll: Nicaragua's dream of its own channel. Chinese investor starts mega-project - with an uncertain outcome. In: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung , Auslandsinformationen No. 8, 2015, pp. 21–39 (PDF) ; Anna Hochleitner: Who pays the bill? The construction of the Nicaragua Canal. In: Friedrich Ebert Foundation , International Policy Analysis, November 2015 (PDF).

- ↑ Volker Wünderich: Nicaragua: History and State. In: LIPortal. last updated in March 2017.

- ↑ Nicaragua has discovered a vaccine for fake news , fusion.tv, May 9, 2018.

- ↑ a b Why the protests escalated in Nicaragua , NZZ, April 23, 2018.

- ↑ In Nicaragua, the circle closes , NZZ, April 24, 2018, p. 13.

- ↑ NZZ, May 12, 2018, p. 2.

- ↑ Human Rights Commission Charges Serious Violations, 76 Deaths In Nicaragua , Today Nicaragua

- ↑ Hundreds of thousands demand the resignation of President Ortega , SRF, May 31, 2018.

- ↑ NICARAGUA: SHOOT TO KILL: NICARAGUA'S STRATEGY TO REPRESS PROTEST , Amnesty, May 29, 2018.

- ^ Agreement on Truth Commission , NZZ , June 18, 2018.

- ^ Mediation by the Church in Nicaragua failed , NZZ, June 20, 2018, p. 2.

- ↑ SRF Nachrichten, June 23, 2018.

- ↑ Canada condemns Nicaragua killings of unarmed protestors . June 23, 2018.

- ↑ a b c 'Everyone is an enemy who's deserving of death, rape and jail': Death squads have returned to Nicaragua , Public Radio International, July 18, 2018.

- ↑ SRF News, July 12, 2018.

- ↑ Act now to end violence, Zeid urges Nicaraguan authorities , UN News, July 5, 2018.

- ↑ Police in Nicaragua take part of government opponents. In: The time. 18th July 2018.