Hamza Hakimzoda Niyoziy

Hamza Hakimzoda Niyoziy ( Cyrillic Ҳамза Ҳакимзода Ниёзий; in Arabic script حمزه حکیمزاده نیازی, DMG Ḥamza Ḥakīm-zāda Niyāzī ; Russian Хамза Хакимзаде Ниязи Chamsa Chakimsade Nijasi , scientific transliteration Chamza Chakimzade Nijazi ; often Hamza Hakimzade Niyazi , also Hamza Hakim-Zade Niyaziy and Hamsa Hakimsade Nijasi ; best known as Hamza ; * February 22nd July / March 6, 1889 greg. in Qo'qon ; † March 18, 1929 in Shohimardon ) was an Uzbek poet , prose writer , playwright and composer .

Niyoziy, whose poetic activity falls around the time of the Soviet takeover in Central Asia, is considered to be the first author of dramas in the Uzbek language and the founder of the Uzbek national musical culture and Uzbek Soviet literature . Substantially influenced by Tatar Jadidism , Niyozzy's career and activities show many characteristics of Central Asian Jadidism. He was a member of the CPSU and after his death was recognized by the Soviets for his literary achievements.

Live and act

Origin and education

Niyozy's father had studied in Bukhara and was one of the most respected pharmacists and healers (called Tabib or Hakim ) in Qo'qon . He also wrote poetry and socialized with the city's literary elite. His extensive travels through the Chinese Turkestan and India indicate a certain wealth.

Hakimzoda Niyoziy was born according to the Julian calendar on February 22nd, 1889 in Qo'qon in the then General Government of Turkestan as the youngest of four siblings. He learned the Uzbek and Persian languages as a child and from 1899 attended an Islamic primary school ( maktab ). In 1905 his father sent him to a madrasah in Qo'qon for lessons . Niyoziy was not satisfied with the 7-year medresen lessons alone and so he began to study the classics of old Uzbek ( Chagata ) literature, the progressive poets of the time such as Muqimiy and Furqat and Uzbek folk art.

Unrest in the years 1905 to 1907 had a lasting influence on Niyozy's worldview. Niyoziy began to write poetry while he was still at the madrasah. At that time, Niyoziy wrote poetry purely in Persian, whereas he only corresponded with his father in Arabic . From 1907 Niyoziy regularly read the Crimean Tatar newspaper Tercuman by Ismail Gasprinski from Bakhchysaraj and the Tatar newspaper Vaqit from Orenburg . As a result, Niyoziy began to think about superstitions , reform of the madrasas, and changes in the lives of people, civilization, and society.

When his family ran into financial difficulties, Niyoziy began working in a cotton mill; at night he continued his western studies and learned the Russian language . He started working as a scribe for Obidjon Abdulxoliq oʻgʻli Mahmudov and went to Bukhara in 1910 with the plan to perfect his Arabic and complete his Koran studies. However, riots had broken out there shortly before, so Niyoziy went to Kogon , where he worked on a printing press, and returned via Tashkent to the Fergana Valley . During his stay in Tashkent learned Niyoziy the Jadidism (Usul-i Jadid) know and their schools the "new method".

After his return, Niyoziy founded a free school for poor children in Qo'qon at the age of 21, which is characteristic of the Jadidist movement, and began to teach, although his own, non-Muslim teaching content snubbed the clergy. Clergymen portrayed him as a godless free spirit and the school was soon closed again, and Niyoziy was banished from Qo'qon. After his marriage in 1912 he began a journey through Afghanistan and India to Arabia , did the Hajj and returned to Qo'qon via Syria , Lebanon , Istanbul , Odessa and Transcaspia (the areas under Russian rule on the Asian side of the Caspian Sea ). During the next five years he founded other schools in Qo'qon and Marg'ilon , most of which only existed for a short time. His textbooks from this time, written for self-use, have not been published.

Before the October Revolution

Niyoziy, who became aware of social inequalities on his travels, recognized common goals with the Bolsheviks in the struggle against tsarism , feudalism and local Beys . He organized a Soviet for working Muslims, began writing verses for the Bolsheviks, and became the most active proponent of reforms from the Fargʻona region . He followed the line of Muqimiys and Furqats, who denounced ignorance and apathy, campaigned for the appropriation of progressive Russian culture in Uzbekistan, and thus paved the way for Niyoziy.

Niyoziy wrote articles for the Jadidist press, and in 1914 his textbook Yengil adabiyot ("easy reading") was published with short stories in verse that call on students to humility, honesty and piety. In 1915, the novel Yangi saodat ("new happiness", also known as Milliy roman , "national novel") was published, which is considered to be the first prose work by a Uzbek. In order to have Yangi saodat printed, Niyoziy collected almost 140 rubles from his friends in July 1914; He probably made a living by teaching, and befriended merchants lent him money if necessary. When Mahmudov published the newspaper Sadoyi Fargʻona ("Voice of Fargʻona") in 1914 , Hamza wrote articles for the paper. In 1915 Niyoziy moved to Marg'ilon.

- Hamza Hakimzoda Niyoziy : Yigʻla Turkiston (refrain)

In: Milliy ashulalar uchun milliy sheʼrlar majmuasi |

He began to train teachers and publish his poems. From 1915 onwards Niyoziy brought out a number of folk song anthologies , the first of which was called Milliy ashulalar uchun milliy sheʼrlar majmuasi (“Collection of national poems for national songs”; Note: milliy can mean “national” as well as “traditional” or “ethnic “To be translated.) Carried. Niyoziy had already completed the manuscript for this volume, which was intended for use in jadidist schools, in February 1913. He sent an inquiry about the printing costs to the Vaqit press in Orenburg, but could not afford the printing, which is why he approached Munavvar Qori from the Tashkent bookstore Turkiston in 1915 . Milliy ashulalar uchun milliy sheʼrlar majmuasi was ultimately printed by Turkiston with an edition of 1,000 copies .

Niyoziy used a more powerful language in this volume than other Jadidists such as Mahmudhoʻja Behbudiy and Munavvar Qori. The latter asked Niyoziy to restrain himself and avoid impolite language after reading his manuscript. Niyoziy brought out the remaining volumes of his folk song series with the help of friends. Since Niyoziy viewed Uzbek songs as the prime of folk art, he named the following anthologies after flowers.

Hoping in this way to convey his ideas to a wider audience in an atmospheric way, Niyoziy began - as the first in the history of the Uzbeks - to write dramatic works around 1915. During these years, Russian Turkestan saw a flourishing of local theaters. Niyoziy himself led an amateur group in Qo'qon, which performed works written or translated by him and with Zaharli hayot yoxud ishq qurbonlari ("The poisoned life or sacrifice of love") had her first engagement in October 1915. The income from Jadidist theater evenings went to reading rooms, schools of the “new method”, field hospitals and the Red Crescent .

Although Niyoziy fought against tsarism, in the face of World War I, like the Jadidist press, he stood behind the Russian empire , the watan to which they felt obliged. In Padishoh hazratlarina duo (“Prayer for His Majesty, the Padischah ”) from the anthology Oqgul (“White Rose”), Niyoziy wrote that the Tsar may live long and the army razed Hungary and conquered and destroyed the German cities. The issue of the series, which appeared in November 1916, was entirely devoted to the events of the war, in it Niyoziy took a position for the participation of his compatriots in the war - previously in June 1916 the exemption from compulsory military service for Central Asians had been withdrawn, which provoked anti-tsarist uprisings , in which above all the rural population was involved.

After the February Revolution of 1917 , there was a dispute over the direction of the desired autonomy. Most of the Jadidists sought cultural autonomy for fear of the influence of the ulama in broader autonomy. The advocates of territorial autonomy around Behbudiy were finally able to prevail, but in retrospect the fear of their opponents was justified. In late spring, Niyoziy was criticized for his harsh tone in an article that was ultimately not printed for the Qo'qon magazine Kengash ("Advice"). In another paper, Niyoziy complained about what he said was worse censorship than before the coup. Radicalized by the rebellions of 1916 and 1917, he organized meetings and demonstrations and soon had to flee to Turkestan, China.

Further publications of his works from the time before the October Revolution are the anthologies Qizil gul ("red rose"), Pushti gul ("pink rose") and Sariq gul ("yellow rose") from 1916. Of his three before the October revolution in Only Zaharli hayot has come down to us for plays written in 1917 . The Central Asia expert and professor emeritus at Columbia University Edward A. Allworth names the theater cycle Fargʻona fojeasi ("the tragedy of Fargʻona") as one of the lost works .

Soviet era

"Do not give up; see, the soviets

woke you up.

For every drop of blood you shed,

you get freedom, education and knowledge.

Welcome the Soviets! Welcome the Soviets!

This is your epoch,

your glory, worker's

son , may it be carried around the whole world. "

During the first years of the Soviet era in Central Asia, Niyoziy and other writers played an important role in the consolidation of Bolshevik rule. Niyoziy, who had started as a democratic enlightener, was able to develop under communist rule and developed into an outstanding revolutionary writer and agitator .

After the Bolsheviks secured power, Niyoziy returned from China. During the civil war that followed, Niyoziy toured with his traveling theater group from Fargʻona, founded in 1918, through the Ferghana Valley and West Turkestan. Western theater was new to the Uzbek audience and suitable for effective propaganda. The Soviets held concerts at which, with free or cheap admission, both Niyozzy's national music was advertised, as well as symphonic works, Russian opera stars and professors from the conservatoires.

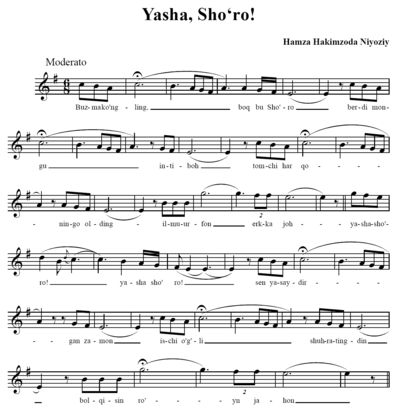

In his last folk song anthology (1919) he also published revolutionary songs such as Yasha, Shoʻro! (“Welcome the Soviets!”) And Hoy, ishchilar (“Hey, workers!”). In 1920 he joined the Communist Party as one of the first Uzbeks . After Soviet rule had consolidated in the early 1920s, Niyoziy traveled extensively through Uzbek territory.

He organized courses to combat illiteracy , on his travels he opened schools, performed plays and skits, propagated a new, Soviet era and campaigned for the liberation of women and against their veiling. For Niyoziy, veiling was associated with corrupt wealth, decayed mullahs, foreign culture, and foreign influences; For Niyoziy, moving away from the veil meant overturning the influence of the rich and the clergy. Eventually he began to distance himself from jadidism. In contrast to most of the Jadidists, who after the tsarist were now fighting the Soviet imperial power, Niyoziy saw the future in the Soviet Union.

Niyoziy joined the Xudosizlar jamiyati , the Uzbek society of the wicked , and was its leader for a time; In 1926 he became a member of the Kurultai of the Ferghana Valley Workers . In the same year the Soviet government named him a national poet .

When he was almost 40 years old, Niyoziy began studying at a Russian music school. In 1928 he moved to Shohimardon , the first five-year plan in his hands.

Niyozy's death in Shohimardon

In Shohimardon, Niyoziy saw to it that a canal, a hydroelectric power station and a tea house were built , he opened a school and created a cooperative. On March 8, 1929, he held the first women's meeting in Shohimardon, at which 23 women took off their paranjah , the traditional clothing that veiled the head and body.

Niyoziy, who had also agitated against the local pilgrimage center venerated as the tomb of Ali ibn Abi Talib in Shohimardon , was lured behind the tea house by Islamists ten days later , where he was stabbed with knives and stoned to disfigure his body . According to one story, Niyoziy led a group who wanted to turn the shrine into a communist museum and was killed for it. His body was thrown into a crevice under the canal and found and buried three days later. The perpetrators who fled Shohimardon were caught.

plant

Niyozy's progressive, revolutionary work was directly linked to the struggle for social justice and liberation in Uzbekistan . In his poems , compositions and dramas , Hamza Niyoziy often deals with the turmoil of the revolution and describes the awakening class consciousness of the Uzbek people.

In his first novel, Yangi Saodat , Niyoziy advocates the Jadidist principle that education is the source of any individual or national benefit. However, he did not write the book for use in schools, but so that it would be read instead of the books popular at the time, which "are all full of superstition, nonsense, detrimental to morality and irrelevant". The content of the novel can be found in a similar form in many Jadidist prosaic and poetic works: Niyoziy tells of a poorly educated young man who has two children with his wife before he becomes a drunkard and gambler and finally leaves the family. His wife takes care of her son, who is taught in a Jadidist school. He graduates from school and learns that his father is still alive and is leading a poor existence in Tashkent. He unites the family and - only because of his education - leads a happy life.

In Zaharli hayot , Niyoziy describes ignorance and the generation conflict : an 18-year-old Jadidist boy falls in love with a 17-year-old girl who, for his sake, begins to read novels and newspapers. The couple want to start a school, but their parents refuse. The boy's parents do not want their son to marry the daughter of a craftsman, but their parents have already promised a 60-year-old with six wives. The two youngsters curse their parents and eventually commit suicide; Niyoziy tries to portray her as a victim of ignorance and a martyr .

Boy ila xizmatchi ("Bey und Knecht", published between 1917 and 1922) reflects the revolutionary activities of the Russians in West Turkestan. In this work, Niyoziy also tells of a girl who commits suicide as a result of her forced marriage . Paranji sirlari ("Secrets of the Veil", 1922) describes the problems of Uzbek women whom Niyoziy called on to actively participate in all areas of society and life.

In his folk song anthologies, Niyoziy provided his poems with special arrangements of Uzbek melodies by matching the music with the character of the lyrics. In his first seven anthologies, Niyoziy collected around 40 songs, most of which he set to music with Uzbek, but also with Kashgarian and Tatar melodies. Niyoziy himself was a master on traditional Uzbek instruments such as dotar and tanbur .

Niyoziy also wrote two comedies with Tuhmatchilar jazosi ("Punishing a Slanderer", 1918) and Burungi qozilar yoki Maysaraning ishi ("The early Qadis or Maysaras thing", 1926). What his works have in common is that they are closely aligned with the Russian-Communist line.

meaning

Before the 20th century, drama had no meaning in Uzbek society. In the first decade of the new century, when Uzbek had just replaced Chagata as the literary language, the drama was institutionalized by Jadidists.

Niyoziy is considered to be one of the most important early exponents of Uzbek literature , the first Uzbek playwright, the founder of the Uzbek national musical culture, and the founder of the Uzbek Soviet literature. His pre-revolutionary plays were considered by Soviet writers to be the beginning of the “ideologically valuable” Uzbek drama. Adeeb Khalid writes in The Politics of Muslim Cultural Reform that the history of modern Central Asian literature is difficult to imagine without the names of Niyoziys, Fitrats , Choʻlpons and Qodiriys .

Those writers from the ranks of the Jadidists who, like Niyoziy, took a pro-Russian position, were the mainstay of non-nationalist Uzbek literature until the emergence of Soviet proletarian authors around 1926. Despite the fact that socialist realism was not adopted until 1932 by the Soviet Central Committee was introduced, Niyoziy is sometimes referred to as the founder of this art movement in the Uzbek SSR .

Niyoziy participated in the Uzbek language reform of the 1920s. The fact that, like Furqat, he began to write prose in addition to his poetry shows the growing Russian influence at the beginning of the 20th century.

Niyoziy broke with the rigid traditions of national poetry and music: with his anthologies he was the first to abandon the traditional path of bayoz songbooks, which were created for outstanding art singers, and instead devoted himself to studying the folk songs, which he was the first Uzbek to collect. Through the revolutionary songs in his last anthology, Niyoziy made a contribution to the further development of the Uzbek art of song by introducing new emotional, melodic and intellectual content to it. As the first Uzbek composer he used the piano , he rejected the oriental way of singing with pressed guttural sounds and he taught to sing standing.

Private life

As with other Jadidists, very little is known about Niyozy's private life and his personal attitudes towards women. Niyozzy's wife, Aksinja Uvarowa, was a Russian who had converted to Islam; their marriage took place shortly before Niyozzy's pilgrimage in 1912. Niyozy's wife appears to have participated in Jadidist activities as she was invited to the annual reviews of the "schools of the new method".

Niyoziy does not seem to have remained childless: The belly dancer LaUra , who was born in Tashkent and lives in the USA, claims to be a great-granddaughter of Hamza Hakimzoda Niyoziy.

Niyoziy in Soviet historiography

To the Soviets, Niyoziy was apparently worth more than alive as they heavily mythified the circumstances surrounding his death, speculates Edward A. Allworth. The Soviet authorities first blamed the Islamic clergy around "fanatical mullas " for Niyozzy's death, but later changed the murderers' biographies to include "lackeys" of imperialism , bourgeois nationalists, dark men and reactionaries on the list of suspects. As a result of Niyozy's murder, nine people were sentenced to death , eight were sentenced to long prison terms, and 17 people were exiled . In 1940 the shrine in Shohimardon was destroyed and replaced by a “Museum of Atheism”, making Shohimardon a symbol of the Soviet struggle against Islam.

According to an analysis of the death of Niyozy by the GPU , he was less an anti-religious activist than still a jadidist who considered certain Islamic attitudes to be oppressive and superstitious and who sought to purify the faith; He saw fanaticism as a distortion of the true religion.

Since Niyoziy died before the Soviets began to denounce jadidism as anti-Soviet, nationalist and counterrevolutionary, he was spared this campaign. Soviet critics even classified Niyoziy as a reformed jadidist. Because of the simplified, class-oriented content and characters in his writings, Niyozzy's literary achievement was later recognized by the Soviets, and his name found its way into Soviet hagiography . He was touted as an outstanding early socialist poet because he understood humanism “intuitively”, not because of a theoretical training.

The Great Soviet Encyclopedia of 1956 writes that Niyoziy used great artistic skill to describe the duplicity and cruelty of the rich, the clergy, the merchants and the colonizers. He had lovingly created pictures of the workers, portrayed their unshakable striving for freedom and happiness and as the first Uzbek writer to show realistically how the Russian proletariat had liberated the workers in the border regions. Viktor Witkowitsch calls Niyoziy in his travelogue A Journey through Soviet Uzbekistan a “flaming herald of the revolution”, a “tribune and organizer” who was a revolutionary and innovator in everything he did. Every step he took was a blow "against everything that had to be removed so that the new, communist truth might triumph".

Soviet biographers, as well as his pilgrimage to Mecca, withheld the fact that Niyozzy's roots and his work lie deep in the tradition of Islamic knowledge reproduced in madrasas. The Soviets repeatedly tried to deny the existence of Uzbek dramas from before the October Revolution, such as Niyoziys Zaharli hayot . The novel Yangi saodat was not republished during the Soviet era due to its jadidic character.

Tributes and criticism

Qizil Qalam (“red feather”), the first strong, ostensibly proletarian group of writers in Uzbekistan, dedicated the second issue of their journal in 1929 to the “martyrs” of communism. In 1932 Hamid Olimjon composed the epic Shohimardon in Niyozy's honor , the Uzbek-Soviet writer Oybek wrote Hamza in 1948, which deals with the life and work of Hamza Niyozy. On October 4, 1949, the Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR held a celebration on the occasion of Niyozy's 60th birthday, in which Oybek, among others, participated.

In 1963 the Wannowski settlement in the Ferghana Valley was renamed Hamza Hakimzoda ( Russian Хамзы Хакимзаде Chamsy Chakimsade ), until 2012 it was briefly called Hamza (since 2013 Tinchlik ). Shohimardon was called Hamzaobod for a time . A mausoleum and museum were built there in the 1960s , and on March 18, 1989, on his 100th birthday, a new museum with a park was opened. In 1989 a 4-kopeck postage stamp and a 1- ruble coin with Hamza Niyozy's portrait were also issued. After Niyoziy, a station of the Tashkent metro and formerly a district bear the name Hamza (today Yashnobod ). There is another Hamza museum in Qo'qon , the drama theater in Tashkent and a sanatorium in Shohimardon named after him. A Hamza Prize was awarded for the first time in 1964 .

Cho'lpon, a writer who did not want to do Soviet propaganda, criticized Niyoziy for his commitment to the Bolsheviks. Uzbek emigrants were outraged when the Soviets stylized the renegade jadidist, anti-Muslim and anti-national Niyoziy into a genuine Uzbek national literary figure. While the people of his hometown respect Niyozy's literary achievement, they add that he would not have chosen his words carefully and that he would not have respected local sanctuaries.

literature

- Article Chamsa Chakimsade Nijasi in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (BSE) , 3rd edition 1969–1978 (Russian)

- Edward Allworth: Central Asia, 130 Years of Russian Dominance . Duke Univ. Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8223-1521-6 . (English)

- Edward Allworth: The Modern Uzbeks: From the Fourteenth Century to the Present: A Cultural History . Hoover Institution Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0-8179-8732-9 (English)

- Edward Allworth: Uzbek Literary Politics . Mouton & Co., The Hague 1964 (English)

- SS Kasymov: Uzbekskaya Sovetskaya Socialisticheskaya Respublika. XIII. Literatura . In: Great Soviet Encyclopedia (1956), pp. 31–34 (Russian); Translation into English by Edward Allworth, The Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic… Literature , in Uzbek Literary Politics , pp. 254–260

- Viktor M. Beliaev: Central Asian Music. Essays in the History of the Music of the Peoples of the USSR (Editor: Mark Slobin; translation from Russian by Mark and Greta Slobin). Wesleyan University Press, Middletown 1975. pp. 316–321 (English)

- Marianne Kamp: The new Women in Uzbekistan. Islam, Modernity, and Unveiling under Communism . University of Washington Press; Seattle, London 2006. ISBN 978-0-295-98644-9

- Adeeb Khalid: The Politics of Muslim Cultural Reform. Jadidism in Central Asia . University of California Press; Berkeley, Los Angeles, London 1998. ISBN 0-520-21356-4 ( online version ; English)

- Sigrid Kleinmichel: A departure from oriental poetry traditions. Studies of Uzbek drama and prose between 1910 and 1934 . Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1993. ISBN 963-05-6316-9 (German)

- David MacFadyen: Russian culture in Uzbekistan . Routledge, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-34134-9 (English)

- Scott Malcolmson: Empire's Edge: Travels in South-Eastern Europe, Turkey and Central Asia . Verso, London 1995. pp. 212–216, ISBN 978-1-85984-098-6 (English)

- Hamza Hakimzoda Niyoziy: Toʻla asarlar toʻplami (Editor: N. Karimov et al.). 5 volumes. Fan, Tashkent 1988–1989 (Uzbek)

- Svatopluk Soucek: A History of Inner Asia . Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-521-65704-4 (English)

- Viktor Witkowitsch: A journey through Soviet Uzbekistan (translation from Russian by Maria Riwkin). Publishing house for foreign language literature, Moscow 1954. pp. 125–129 (German)

Web links

- Adeeb Khalid: Printing, Publishing, and Reform in Tsarist Central Asia (PDF file; 1.87 MB). 1994 (english)

- Mark Dickens: Uzbek Music (PDF file; 174 kB). 1989 (english)

- Mark Dickens: The Uzbeks (PDF file; 280 kB). 1990 (english)

- Biography on ziyouz.com (Uzbek)

- Selection of his works on geocities.com ( Memento from March 25, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (English, Russian, Arabic)

- Report about Shohimardon on fdculture.com (English)

- Report about Shohimardon on ferghana.ru (English)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Niyoziy, Hamza Hakimzoda |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ниёзий, Ҳамза Ҳакимзода (Cyrillic-Uzbek); Ниязи, Хамза Хакимзаде (Russian); حمزه حکیمزاده یزنیا (Arabic script); Niyasi, Chamsa Chakimsade; Niyazi, Hamza Hakimzade |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Uzbek writer and composer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 6, 1889 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Qo'qon |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 18, 1929 |

| Place of death | Shohimardon |