Haram (holy district)

The term haram ( Arabic حرم, DMG ḥaram 'forbidden, inviolable, inviolable, sanctuary') in Islam denotes the holy area around a place of pilgrimage. The most extensive district of this type is the haram around the city of Mecca , which has pre-Islamic origins. It covers an area of 554 square kilometers, in the center of which is the Holy Mosque with the Kaaba . A less spacious Haram district also exists in Medina . The two sanctuaries in Mecca and Medina are referred to in Arabic with the dual as the "two harams" ( al-ḥaramān , or inflected al-ḥaramain ). This dual form also occurs in the Islamic title servant of the two holy places ( ḫādim al-ḥaramain ), which the Saudi kings wear today .

A number of prohibitions apply to the two haram districts. For example, non-Muslims are not allowed to enter them. In addition to Mecca and Medina, the shrines of Jerusalem and Hebron are also referred to as haram, but their haram status is controversial among Muslim scholars. The Twelve Shiites also consider some of their pilgrimage sites to be haram districts.

The Arabic words Harām ( ḥarām ) and Mahram ( maḥram ) and the German word Harem (from Arabic ḥarīm ) are related to the word Haram : They are all from the Arabic root ḥ-rm , which means something "forbidden, inviolable, inviolable" designated, derived.

Haram districts in pre-Islamic Arabia

The Haram of Mecca

The Haram of Mecca was probably a sacred area long before Mohammed. In the Meccan local chronicle of al-Azraqī it is reported that in the time before Qusaiy ibn Kilāb it was forbidden to build houses next to the Kaaba. People only stayed in the Holy District during the day and moved out to the Hill area in the evening. Sexual acts were also not allowed in the field of haram. When Qusaiy and the Quraish brought the Holy District under his control, he allowed people to build houses in the area of the Haram and to settle there. Qusaiy ibn Kilāb also allowed the Quraish to cut down trees of haram for their houses, which they had not dared to do before.

Fighting and killing were forbidden within the haram. The haram was also an asylum area. Even murderers or manslaughters were not allowed to be killed here. Al-Azraqī (d. 837) reports: "When a manslaughter ( qātil ) entered the haram, one was not allowed to sit with him or sell him anything. And one was not allowed to shelter him either. The one who was looking for him spoke to him : 'So-and-so, fear God because of the bloodshed against so-and-so and leave the holy places'. Only when he left the haram was the hadd punishment carried out on him. " With this ban on killing, Qusaiy ibn Kilāb is said to have established the settlement of the Quraish on the Haram: If they lived there, they would be feared by the Arabs; it is then no longer allowed to fight or drive them away. Those who inadvertently killed someone and then tied some of the bark of the haram trees around their necks were also included in the ban on killing. One could then no longer practice retaliation against them.

The Qur'an also refers to the Haram . So in sura 28:57 the Meccans, who fear a violent expulsion from their city if they follow the teachings of Muhammad , are countered with the words: " Did n't we give them power over a safe haram ( ḥaram āmin ) for the fruits of all Kind of collected - as a supply from us? Yet most of them have no knowledge ". And in Sura 29:67 it says: "Yes, have they not seen that we have created a safe Haram ( ḥaram āmin ) while the people around are being dragged away?" Mohammed himself is said to have shown great respect for the haram. It is said that during his 40-year stay in Mecca, he never urinated or had a bowel movement in the area of the haram.

The layout of the Haram in Mecca was ascribed to the progenitor Abraham in pre-Islamic times . This emerges from a tradition handed down by the Baghdad scholar Muhammad ibn Habīb (d. 860). Accordingly, in pre-Islamic times, many Quraish settled in the Vajj valley, in which the city of at-Tā'if is located. When they proposed an alliance to the Thaqīf, the Arab tribe residing in at-Tā'if, which provided that the Quraish should participate in the valley of Wajj in the same way as the Thaqīf should participate in the haram of Mecca, The Thaqīf rejected this proposal, arguing that Wajj was laid out by their own ancestors, but the Haram of Mecca was a shrine laid out by Abraham, the establishment of which the Quraish had no part in. Since the Quraish exerted strong pressure on the Thaqīf, they were eventually forced to enter into an alliance with the Quraish.

Other haram districts

In addition to the Haram of Mecca, there were a few other places in pre-Islamic Arabia that were considered haram. For example, Abū l-Faraj al-Isfahānī quotes a poem that speaks of a haram in ʿUkāz . The same author also provides a report according to which members of the Arab tribe of Ghatafān in pre-Islamic times tried to found a haram based on the model of the haram of Mecca in a place called Buss after they had triumphed over the tribe of the Sudāʿ and felt particularly strong. Zuhair ibn Janāb, who was the leader of the Banū Kalb at the time, is said to have thwarted this operation and beheaded one of the prisoners on the spot as a sign that the haram was null and void. From Ibn al-Kalbī's "idol book" it is known that there was a sanctuary of al-ʿUzzā in Buss .

At-Tabarī also reports that Musailima set up a haram in the region of al-Yamāma and declared it inviolable. In this haram were the villages of his allies of the Banū Usaiyid, who had settled in al-Yamāma. During the fertile period they raided the crops of the residents of al-Yamama and then took the haram as a retreat. Harry Munt suspects that the haram in pre-Islamic Arabia was an institution with which a "form of sacred space" could be created that enabled the establishment of "structures of social leadership".

The Haram of Mecca in Islam

history

After the conquest of Mecca in 630, Mohammed had the boundaries of the haram redesignated by Tamīm ibn Asad al-Chuzāʿī. According to a hadith which is narrated by ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAbbās and which was also included in the canonical collection of hadiths by Muslim ibn al-Hajjāj , he is said to have said on this occasion:

“God declared this land inviolable on the day he created heaven and earth. And because of the inviolability of God, it is inviolable until the day of resurrection. No one was allowed to fight in it before me. And I'm only allowed to do this for one hour a day. It is inviolable until the day of resurrection. Neither his plants may be cut off nor his wild animals hunted. "

This hadith forms the basis for the Islamic teaching of the holiness of the Meccan haram. In it it is reported that al-ʿAbbās ibn ʿAbd al-Muttalib then asked Mohammed for a special permit for the idhchir, a type of lemongrass , because it was needed in Mecca for building houses. The request was granted to him.

Further renewals of the haram border markings took place in the year 17 of the Hijra (= 638 AD) by ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb , in the year 26 (= 646/47 AD) by ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān and later by Muʿāwiya I. (reg. 661-680). The early Muslims continued to apply strict rules regarding haram. From ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAmr (d. 683 or 685) it is narrated that when he was in Mecca he pitched two tents, one in the hill and the other in the haram. If he wanted to scold his wives, he did it at the Hill. But if he wanted to pray , he did it in the haram. When asked about it, he said that he had been taught that in haram one should not swear . Many legal scholars also considered it frowned upon to bring stones or earth out of the hill into the haram or to move them out of the haram into the hill. It is reported from allAbdallāh ibn az-Zubair (d. 692) that he had white gravel that had been strewn in the courtyard around the Kaaba removed after he learned that it came from the area outside the haram because he considered it forbidden to mix stones from the Hill with stones from the Haram.

In the Islamic tradition, the opinion spread that the first marking of the boundaries of the Haram area with stone paintings was made by Abraham at the behest of the angel Gabriel . Even in later times these stone marks were renewed again and again, for example under the Umayyad ʿAbd al-Malik (r. 685-705) and the Abbasid al-Mahdī (r. 775-785). The Abbasid caliph ar-Rādī (934-940) renewed the two large stone monuments of Tanʿīm in 936/937 and put an inscription with his name on them; the Begteginide al-Muzaffar renewed the large stone monument at ʿArafāt in 1219. The latter was set up again in 1284 by the Rasulid al-Muzaffar.

Limits

Its limits are defined by the classic Arab authors using the following points on the arteries of Mecca:

| direction | Location of the boundary point | Distance to the Holy Mosque |

|---|---|---|

| Medina | Tanʿīm, below by the houses of the Ghifār or Muʿādh | 5.4 - 6.1 km |

| Yemen | Libin mountain slope at the pond of the same name | 12-17 km |

| Jeddah | "Breakthrough of the Nests" ( munqaṭiʿ al-aʿšāš ) | 18.3 - 20 km |

| Typh | The end of the level 'Arafāt the share of Namira | 12 - 18.3 km |

| Iraq | Chull mountainside, now Wādī Nachla Road | 12.8 - 14 km |

| east | Jiʿrāna, valley of the clan ʿAbdallāh ibn Chālid ibn Usaid | 16-18 km |

The boundary points of the Haram are marked by stone monuments, the so-called anṣāb al-ḥaram . They separate the Haram from the Hill area (see below). In addition, at the time of Muhammad, a Haram border point was in the village of Hudaibiya. With more than a day's journey, this border point was particularly far from Mecca and in a sense represented a "bulge" ( zāwiya ) of the haram.

The boundaries of the haram are now also marked at the following points: 1. on the expressway to Jeddah, 21 kilometers away, 2. on the road to Yemen, 20 kilometers away, 3. on the new Hudā road to at-Tā'if 14.6 kilometers away and 4th on the Sail expressway to at-Tā'if at 13.7 kilometers away. The Saudi scholar ʿAbd al-Malik Ibn Duhaisch (died 2013) in his Haram monograph from 1995 provides an even more precise definition of the Haram boundaries with over 40 boundary points.

Rules for the Haram

According to classical Islamic teachings, a number of special provisions apply to the Haram of Mecca. According to al-Māwardī , they can be divided into five groups:

- Muslims who come from outside are only allowed to enter the haram in the state of consecration , whereby in the state of consecration it must be specified whether it applies to the Hajj or the ʿUmra . The only exceptions are people who cross the border to the Haram every day for professional reasons.

- There is a ban on fighting within the haram. Whether this also applies to the fight against rebels, is among the Muslim scholars disputed . There were also different views regarding the execution of hadd sentences . While al-Shafiʿī considered this to be permissible in the field of haram, Abū Hanīfa said that a hadd punishment may only be carried out in the haram if the underlying crime was also committed in the field of haram.

- Hunting game ( ṣaid ) that is in the area of the Haram may not be killed; Animals that have already been caught must be released. The ban on killing does not apply to harmful predators ( sibāʿ ) and reptiles ( ḥašarāt al-arḍ ). It is also allowed to slaughter and keep pets .

- Wild plants of the haram may not be cut off, unlike plants that have been planted by humans, to which this ban does not apply. Violations of the prohibition must be atoned for through acts of sacrifice. For example, a cow must be sacrificed to cut a large tree and a sheep to be felled.

- Non-Muslims are not allowed to enter the haram. The basis for this rule is sura 9:28 : "The companions are truly unclean. Therefore, after the end of this year they should no longer come close to the Holy Mosque ." While according to al-Shāfidī interpreted this prohibition in such a way that non-Muslims are neither allowed to stay on the haram, nor are they allowed to pass through it, Abū Hanīfa ruled that there was nothing wrong with passing it as long as the person does not settle on the haram.

As for the plants of the haram, Alī al-Qārī distinguishes four types: (1) Plants that are planted by people and of the kind that people usually grow, such as grain ; (2) Plants that are planted by humans but not ordinarily grown by humans, such as the arāk tree ; (3) Plants that are self-grown but are usually grown by humans; (4) Plants that are self-grown and not usually grown by humans, such as Acacia gummifera ( umm ġīlān ). While the first three types may be cut off and uprooted, cutting off and uprooting the fourth type is forbidden for people in the state of consecration. The only exceptions from this prohibition are dried plants and the Idhchir, which is already mentioned in the above mentioned hadith by ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAbbās.

The hill as an area in front of the haram

The Hill (حل / ḥill / 'permitted district') is an outer ring that surrounds the haram and represents a preliminary area of holiness. Like the haram, it also has transition points at the outer border, the so-called mawāqīt (from singular mīqāt ). Overall, the Kaaba is surrounded by three concentric rings: The narrowest ring is formed by the Holy Mosque, the second ring by the Haram, and the third by the hill with the Mawāqīt. Anyone who crosses the third ring with the intention of entering the haram has a duty to enter the Ihrām state. This includes putting on special clothing and reciting the Talbiya. Basically, pilgrims who want to enter the state of consecration must do so on the mīqāt that is intended for their region. The individual mawāqīt are:

| Mīqāt | location | Distance from Mecca |

for pilgrims from ... |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dhū l-Hulaifa | 10 km south of Medina | 10 day trips | Medina |

| Al-Dschuhfa | near Rābigh north-northwest of Mecca | 3 day trips, or approx. 200 km |

Syria, Egypt and the Maghreb, who enter via Tabūk . |

| Qarn al-Manāzil | east of ʿArafāt | 2 day trips | the najd |

| Yalamlam | Mountain in the Tihāma | 2 day trips | the Yemen |

| Dhāt ʿIrq | Border between the Tihama and the Najd, northeast of Mecca. The place is named after the mountain ʿIrq, which rises here above the valley. | 2 day trips, or 94 kilometers |

Iraq, Persia and Central Asia. |

The Sheikh of the Haram

During the Ottoman period, the Ottoman governor in Jeddah held the title of " Sheikh of Haram" ( šaiḫ al-ḥaram ). He was responsible for all the pious foundations for the maintenance of the holy places and had to go to Mecca every year to oversee the pilgrimage. The entire staff of the Holy Mosque was also subordinate to him.

The Haram of Medina

Justification by Mohammed

After moving to Medina, which at that time was still called Yathrib, Mohammed also declared the valley of this place to be a haram. This emerges from the municipal code of Medina , among other things . In the variant that Ibn Hishām narrates from this document, it is explained at the end: "The valley ( ǧauf ) of Yathrib is inviolable for the comrades of this writing ( wa-inna Yaṯrib ǧaufa-hā ḥarām li-ahli hāḏihī ṣ-ṣaḥīfa )" . In another variant of the document, which is passed down by Abū ʿUbaid ibn Sallām (d. 838), the passage in question does not contain ḥarām , but ḥaram . The difference can probably be explained by the fact that in the early Islamic period the difference between the long and the short a was not always marked in the scriptures. Whatever the sound, the text shows that the signatories of the document recognized the area of Medina as an inviolable haram, because arām is only an adjective derived from ḥaram . Those who signed the document included the emigrants from Mecca, the Aus and Khazradsch from Medina, and some Jewish tribal groups.

It is believed that the transformation of the area of Medina into a Haram took place in 628 after the Khaibar campaign because there is a hadith narrated by Anas ibn Mālik that says this. In this hadeeth, which is also included in the Saheeh al-Buchari , Anas ibn Malik is quoted as saying:

“I went out to Khaibar as a servant with the Messenger of God . When the Prophet returned and Uhud appeared before him, he said, 'This is a mountain that loves us and that we love.' Then he pointed his hand at Medina and said, 'O God. I make what lies between his two lava fields inviolable, just as Abraham made Mecca inviolable. '"

According to a hadith that Abū Yūsuf cites in his Kitāb al-Ḫarāǧ , Mohammed even used the Koranic expression ḥaram āmin ("safe haram") for Medina .

Harry Munt suspects that the establishment of a haram in Medina had the function, on the one hand, of ending the longstanding conflicts between the various tribal groups within this area, because a haram included the prohibition of fighting and quarreling, on the other hand, as with the haram von Buss served as a symbolic means to externally show one's own power and independence, which was very important for Mohammed in his dispute with the Quraish of Mecca.

Limits

There are a number of hadiths beyond the boundaries of the Haram of Medina. There is , however, great confusion about the toponyms that occur there, because most of them forgot at an early stage which localities they refer to. The term ǧauf ("valley"), which is used in the municipal code of Medina for delimitation, does not appear in any of these hadiths. From this, Munt concludes that the boundaries of the medical haram have changed several times since this document was written.

From Mālik ibn Anas (d. 795) the view is passed down that the haram of Medina actually consists of two harams, a haram for birds and wild animals, which extends from the eastern to the western lava field, and a haram for trees, which extends into each Direction extends over a barid. Munt assumes that the two harams overlapped and that the haram of the animals was the narrower haram, in which there was also a general ban on killing, while the outer haram was actually a himā ("protection zone"); He concludes this from the fact that various traditions from the Umayyad period mention a Himā for Medina.

The geographer Shams ad-Dīn al-Maqdisī , who lived at the end of the 10th century, stated, however, succinctly: "What is between the two lava fields of Medina is a haram like the haram of Mecca." Here he was probably based on the hadith of Anas ibn Mālik.

Discussions about Haram status and Haram rules

Discussions about the Haram status of Medina were already being held in the time of the Companions of the Prophets . When the caliph Marwān ibn al-Hakam was preaching a sermon in which he mentioned the holiness of Mecca, Rāfid ibn Khadīdsch (d. 693) from the Medin tribe of Aus interrupted him and reminded him that not only Mecca but also Medina is a haram. He had been declared a haram by the Messenger of God. Rāfid said this was written on a parchment that he could read to him. Marwān replied that he had already heard of this.

Extensive discussions about the haram status of Medina were also held within Fiqh . It is narrated that the sixth Imam Jafar as-Sādiq (d. 765) gave a negative answer to the question whether the same prohibitions apply in the Medin haram as in the Meccan haram. Abū Hanīfa (d. 767) is said to have not recognized the special status of Medina and considered it permitted to hunt game and cut off plants in his area. Ibn Abī Schaiba (d. 849) reports from him that he did not consider the hadith of the Medinian haram to be reliable. The Hanafit at-Tahāwī (d. 933) also questioned the existence of a haram in Medina. He argued with a hadith according to which Mohammed had allowed a boy to capture a small bird in the area of the haram, and with the fact that, unlike in Mecca, people who want to enter Medina do not have to enter the state of ordination. This became the standard position on this question among the Hanafis .

Ahmad ibn Hanbal (d. 855), on the other hand, narrated a hadith according to which Mohammed not only declared Medina to be a haram, but also imposed a number of prohibitions on it. According to this hadith, Muhammad said:

“Every prophet has a haram, and my haram is Medina. O God, I make it inviolable because of your sacred things, so that the lawbreaker is not sheltered, his herbs not plucked, his thorns not cut off, and his lost property not picked up, except by whoever calls them. "

The Hanbalites , Shafiites and Malikites have later repeatedly reaffirmed the Haram status of Medina, but also made it clear that violations of the Haram rules will not be punished.

Abū Sulaimān al-Chattābī (d. 998) said that Mohammed only declared the city of Medina to be a haram in order to “worship its holiness” ( taʿẓīm ḥurmatihā ), but not to declare its wild animals and plants inviolable. Al-Jahiz (d. 869) occupied a similar position outside of fiqh . In his Kitāb al-Ḥayawān he suggested that Medina had been made a sign ( āya ) of God with the elevation to Haram , which is evident from the good smell that emanates from its soil. The local medical historian as-Samhūdī (d. 1533) established the Haram status of Medina with the veneration of Muhammad, who had worked here, but also said that the Haram rules were valid. In his local medical history, Wafāʾ al-wafā bi-aḫbār Dār al-Muṣṭafā , he writes:

“Know that what one can gather from the establishment of the Haram is the exaltation and veneration of the noble Medina, because this is where the noblest of creatures (sc. Mohammed) has settled and its radiant splendor and blessings spread over his land to have. Just as God has set up a haram for his house (sc. The Kaaba ), which serves his worship, he has also created a haram for his beloved and his most noble creature from what surrounds his place. His rules are imperative and his blessings are attainable. What is good here, in blessings, radiant shine, short and long-term peace, cannot be found anywhere else. "

Although the haram status of Medina was controversial, Mecca and Medina were often referred to as the "two harams" ( al-ḥaramān , or inflected al-ḥaramain ) since the 11th century . The expression occurs, for example, in the honorary title Imām al-Ḥaramain ("Imam of the two harams") by al-Juwainī (d. 1085).

The haram of Wajj

After taking Mecca in 630, Mohammed recognized the Wajj valley, in which at-Tā'if is located, as haram in a treaty with the Thaqīf tribe. It was therefore forbidden to cut plants or hunt wild animals there. The treaty concluded with the Thaqīf also stipulated that they had a privilege to the Vajj valley, that no one was allowed to enter the city without their permission and that the city's governors should always come from their ranks. In this way Mohammed tried to end a long-running dispute between the Thaqīf and the Quraish over the use of the gardens of Vajj.

The agreement quickly lost its importance, however, because a short time later at-Tā'if was fully integrated into the state founded by Mohammed. While Muhammad was still alive, a Quraishit, ʿUthmān ibn Abī l-ʿĀs, was appointed governor of at-Tā'if, and another Quraishit, Saʿd ibn Abī Waqqās , took over the administration of the Protected District ( ḥimā ) of Wajj.

According to a hadith that Ahmad ibn Hanbal narrates in his Musnad , the companion of the Prophet al-Zubair ibn al-ʿAuwām heard Mohammed say: "The wild animals and thorns of Wajj are a haram that has been made inviolable for God's sake." of this hadith and the tradition of the contract between Mohammed and the Thaqīf, al-Shāfiʿī taught: "Wajj is a haram, the wild animals and trees of which are inviolable." Most other Sunni scholars, however, consider the hadith mentioned to be weak and therefore have the haram - Wajj status not recognized.

In addition to these discussions about the haram status of Wajj, there are other statements that explicitly attribute holiness to the valley. The Medinan legal scholar Saʿīd ibn al-Musaiyab of ʿUmar ibn al-Chattāb has narrated that he called Wajj a “sacred valley” ( wādī muqaddas ). And Abū ʿUbaid al-Bakrī (d. 1094) quotes an anonymous author in his geographical dictionary Kitāb al-Muʿǧam mā staʿǧam with the statement: “Wajj is a sacred valley. From him the Lord - blessed and exalted is He - ascended into heaven when he had completed the creation of heaven and earth. "

As a name for the shrines in Jerusalem and Hebron

In some orientalist works, the term Haram is used as a name for the Jerusalem Temple Mount as early as the early Islamic period , but this is an anachronism because there is no evidence that Jerusalem or the Temple Mount was called Haram before the late 12th century .

The Sermon of Ibn Zakī ad-Dīns and the Peace of Jaffa

A tendency to ascribe a Haram to Jerusalem first appeared after the Islamic reconquest of the city from the Crusaders by Saladin in 1187. As various Arab sources report, the Damascus legal scholar Ibn Zakī ad-Dīn (d. 1202) followed up on Friday Conquest of the city on behalf of Saladin a famous sermon in which he describes Jerusalem as "the first of the two qiblas, the second of the two mosques and the third of the two harams" ( auwal al-qiblatain wa-ṯānī al-masǧidain wa-ṯāliṯ al -ḥaramain ) praised. With the expression "first of the two qiblas" he alluded to the fact that in the early days of Islam Jerusalem had served as a qibla for a time, and with the expression "second of the mosques" he referred to the tradition of Muhammad's night journey from the Holy Mosque to the al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem. The expression "third of the two harams", which was actually an oxymoron , made it clear that Jerusalem is not a haram, but equals it. An Arabic inscription, four years later, in 1191, in the Qubbat Yūsuf on the Temple Mount, on the other hand, still clearly separated the status of the two cities in the Hejaz on the one hand and Jerusalem on the other. Here Saladin is referred to as "servant of the two noble haram districts and this sacred house" ( ḫādim al-ḥaramain aš-šarīfain wa-hāḏa al-bait al-muqaddas ).

By the early 13th century at the latest, the expression al-ḥaram aš-šarīf ("the noble haram") for the Temple Mount was firmly established. Thus, the Arab historian reported Ibn Wasil (d. 1298) in his Ayyubids -Chronik Mufarriǧ al-kurūb fī Ahbar Banī Aiyub that the 1229 between al-Malik al-Kāmil and Frederick II. Closed Treaty of Jaffa, by the majority of Jerusalem was returned to the Christians, the regulation provided that the "noble haram with the sacred rock and the al-Aqsā mosque on it" should remain in the hands of the Muslims; the “symbol of Islam” ( šiʿār al-islām ) should be visible on it, the Franks should only be allowed to visit the place , and Muslim officials should administer the place.

Mamluk period

At the latest at the time of the Mamluk sultan az-Zāhir Baibars (r. 1260–1277), the tomb of the patriarchs in Hebron was also considered a haram. This emerges from a brief note by the Syrian historian ʿIzz ad-Dīn Ibn Shaddād (d. 1285), who reports that this ruler whitewashed the Hebron haram, prepared its crumbling doors and cleaning basins, paved the floor and his staff paid salaries. The fact that the sanctuary of Hebron was now regarded as a haram may have something to do with the fact that az-Zāhir Baibars forbade Jews and Christians access to it in 1266. The number of haram districts thus rose to four in total: For the year 697 of the hijra (= 1297/8 AD) there is a certificate of appointment for an "overseer of the two noble haram districts of Mecca and Medina and of the two harams Jerusalem and Hebron "( nāẓir al-ḥaramain aš-šarīfain Makka wa-l-Madīna wa-ḥaramai al-Quds wa-l-Ḫalīl ). Ibn Taimīya (d. 1328) turned against this extensive use of the term haram as early as the 14th century . He wrote in one of his fatwas :

“There is no haram either in Jerusalem ( Bait al-Maqdis ) or at the tomb of Hebron ( turbat al-Ḫalīl ), nor in any other places, but only in three places: the first is the haram of Mecca, according to the consensus of all Muslims; the second is the Haram of the Prophet (sc. in Medina) [...] according to the majority of scholars such as Mālik, Ash-Shāfiʿī and Ahmad, and there are plenty of valid hadiths about this; and the third is Wajj, a valley in at-Tā'if, […] and this is a Haram according to Ash-Shāfiʿī, because he considers the hadith to be correct. However, most scholars believe that it is not a haram. […] But what goes beyond these three places is not regarded as haram by any of the Muslim scholars. Because a haram is that in which God has made wild animals and plants inviolable. But God has not done that in any other place except these three. "

The Jerusalem scholar Ibn Tamīm al-Maqdisī (d. 1364), who a short time later wrote a book about the visit to Jerusalem and various other places of pilgrimage in Syria, expressed similar rejection . In a long list of names for Jerusalem and its sanctuary, he declares that the mosque of Jerusalem ( masǧid Bait al-Maqdis ) should not be called Haram .

Nevertheless, it became common practice to regard the two pilgrimage sites in Jerusalem and Hebron as harams. The office of Nāẓir al-Ḥaramain ("overseer of the two Haram districts") continued to exist throughout the Mamluk period, but was no longer associated with a responsibility for Mecca and Medina, but only referred to Jerusalem and Hebron. The Nāẓir al-Ḥaramain was a venerable official who was responsible for the preservation of the two sanctuaries and the administration of their foundations and who had to show piety in addition to administrative skills. Often this office was combined with other offices such as the post of governor of Jerusalem. The Hanbali scholar Mujīr ad-Dīn al-ʿUlaimī (1456–1522), who wrote a story of Jerusalem and Hebron, also reinterprets the title “servant of the two noble Haram districts” by referring to these two cities. He dubbed the ruling Mamluk Sultan Kait-Bay (ruled 1468–1496) as a "servant of the two noble Haram districts, the al-Aqsa mosque and the mosque of Hebron, sun and moon".

Ottoman period

The Ottoman rulers seem to have hardly used the term haram for Jerusalem until the 19th century. When Mahmud II had extensive renovations carried out on the structures on the Temple Mount in 1817 , inscriptions were placed above them in five different places, including in the Dome of the Rock . In these inscriptions the Ottoman Sultan is titled as "servant of the two noble Haram districts and this most distant mosque, the first of the two Qiblas" ( ḫādim al-ḥaramain aš-šarīfain wa-hāḏā al-masǧid al-aqṣā auwal al-qiblatain ) . This shows that the Ottoman state at that time did not regard the Temple Mount as a haram, but instead used the Koranic term al-Masjid al-aqsā for it.

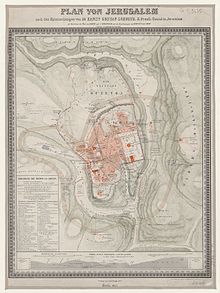

With the local population at this time the expression al-Ḥaram aš-šarīf ("the noble haram") seems to have continued to be used for the Temple Mount, for the Scottish traveler Robert Richardson (1779-1847), who visited the Temple Mount around 1816 visited in the company of a local Muslim, uses this expression throughout his description of his visit. As Richardson reports, access to the holy precinct was strictly forbidden to non-Muslims at the time. The Prussian consul Ernst Gustav Schultz , who stayed in Jerusalem from 1842 to 1845, was also familiar with this term. In his Jerusalem book, which he published in 1845, he describes a tour through the old city of Jerusalem and explains at one point: "Here we enter the north-west corner of Mount Zion . A main road runs straight ahead from the gate to the great one Mosque, called al-Harâm el-Sherîf or preferably al-Harâm . " In the same year the cartographer Heinrich Kiepert published a map of Jerusalem based on Schultz's research, in which the Haram was first drawn.

The French archaeologist Charles-Jean-Melchior de Vogüé wrote the first monograph on the Jerusalem Haram in 1864. In it he describes that ten years earlier Christians were denied access to the haram, but that on a second visit to Jerusalem a baksheesh opened the doors to the haram for them. In the early 20th century at the latest, the Ottoman side also used the term al-Ḥaram aš-šarīf for the Temple Mount. This can be seen from the fact that in 1914 the Ottoman official Mehmed Cemil Efendi published a booklet with the title Tarihçe-i Harem-i Şerîf-i Kudsî (“ Short History of the Jerusalem Noble Haram”) in which he describes the various buildings the temple square.

After the end of the Ottoman rule

Another story of the Jerusalem Haram was written in 1947 by the Jordanian official Aref al-Aref , who served as Lord Mayor of East Jerusalem from 1950 to 1955 . It was translated into English in 1959 under the title “A brief guide to the Dome of the Rock and al-Haram al-Sharif”.

To this day, however, the term haram is rejected in some Islamic circles as a term for Jerusalem and the Abraham mosque in Hebron. For example, the Saudi preacher Muhammad Sālih al-Munajid rejected such use of the haram term as an inadmissible expansion of meaning in a fatwa from 2003. It stands on the same level as the use of the expression ḥaram ǧāmiʿī as a name for the campus of a university. In reality, there are only three haram districts that Ibn Taimīya named in his fatwa. The Palestinian scientist ʿAbdallāh Maʿrūf ʿUmar has also made a particular decision against the use of the term haram in connection with Jerusalem. In his book "Introduction to the Study of the Blessed Al-Aqsā Mosque" ( al-Madḫal ilā dirāsat al-Masǧid al-aqṣā al-mubārak ) published in 2009, he calls for the expression al-Aqsā mosque to be used for the entire Temple Mount including the To use the Dome of the Rock and to drop the common expression al-Ḥaram al-Qudsī aš-šarīf ("the noble Jerusalem haram") because the rules of a haram for the Temple Mount do not apply.

Shiite Haram districts

There are also a number of Shiite harams. This includes in particular that of Kufa . Abū Jafar at-Tūsī (d. 1067) narrates the statement from the sixth Shiite Imam Jaʿfar as-Sādiq : "Mecca is the Haram of Abraham, Medina is the Haram of Mohammed and Kufa is the Haram of ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib . ʿAlī has of Kufa for declared inviolable what Abraham of Mecca and what Mohammed of Medina declared inviolable. " And the fourth Imam Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abidin was quoted as saying that God already 24,000 years before he created the earth and the Kaaba ausersah as Haram, the earth of Karbala have been chosen as a safe and blessed Haram.

In later times the area around the tomb mausoleum of ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib in Najaf was elevated to the status of haram. The basis for this is a tradition according to which the Abbasid caliph Hārūn ar-Raschīd once made a hunting trip to the two Gharys, two towers on the site of today's tomb mausoleum, and the hunting dogs and hunting falcons sent by him shied away from the game on a certain hill to follow. When he had a sheikh from Kufa come and asked him about the hill, the latter explained to him: "My father told me about his forefathers that they used to say: This hill is the grave of ʿAlī ibn Abī Tālib. God has it made into a haram. Everything that takes refuge in him is safe. "

The Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad is called Haram-e Emām-e Rezā in Persian .

literature

- swell

- Abū ʾl-Walīd al-Azraqī : Aḫbār Makka wa-mā ǧāʾa fī-hā min al-āṯār . Ed. Ferdinand Wüstenfeld under the title The Chronicles of the City of Mecca. Volume I. History and description of the city of Mecca [...]. Leipzig 1858. pp. 351-380. Digitized

- Muḥammad ibn Amad al-Fāsī: Taḥṣīl al-marām min tārīḫ al-balad al-ḥarām . Ed. Maḥmūd Ḫuḍair al-ʿĪsāwī. Dīwān al-Waqf as-Sunnī, Baghdad, 2013. Vol. I, pp. 202–238.

- ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Muḥammad al-Ḥuwaiṭān: Aḥkām al-Ḥaram al-Makkī as-šarʿīya . Self-published, Riyadh, 2004. Digitized

- Ibn Abī Shaiba : Kitā al-Muṣannaf . Ed. A.-A. Ǧumʿa and MI al-Luḥaidān. Maktabat ar-Rušd, Riyad: 2006. Vol. XIII, pp. 123-125. Digitized

- ʿAbd al-Malik ibn ʿAbdallāh Ibn Duhaiš: Al-Ḥaram al-Makkī aš-šarīf wa-l-aʿlām al-muḥīṭa bi-hī. Dirāsa tārīḫīya wa-maidānīya . Maktaba wa-Maṭbaʿat an-Nahḍa al-Ḥadīṯa, Mecca, 1995. Digitized

- Ibn Rusta : Kitāb al-Alāq an-nafīsa . Ed. MJ de Goeje . Brill, Leiden, 1892. pp. 57f. Digitized

- Abū l-Ḥasan al-Māwardī : al-Aḥkām as-sulṭānīya . Ed. Aḥmad Mubārak al-Baġdādī. Kuwait 1989. pp. 212-216. Digitized

- Qutb ad-Dīn an-Nahrawālī: Kitāb al-Iʿlām bi-bait Allāh al-ḥarām . Ed. F. Wüstenfeld under the title The Chronicles of the City of Mecca . Volume III. Leipzig 1857. Digitized

- ʿAlī al-Qārī : al-Maslak al-mutaqassiṭ fi l-mansak al-mutawassiṭ . Beirut: Dār al-Kitāb al-ʿArabī ca.1970.

- Ibrāhīm Rifʿat Bāšā: Mirʾāt al-ḥaramain: au ar-riḥlāt al-Ḥigāzīya wa-l-ḥaǧǧ wa-mašāʿiruhū ad-dīnīya . Dār al-kutub al-Miṣrīya , Cairo, 1925. Vol. I, pp. 224-227. Digitized

- Nur ad-Dīn Abū l-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn ʿAbdallāh as-Samhūdī: Wafāʾ al-wafā bi-aḫbār Dār al-Muṣṭafā . Ed. Muḥammad Muḥyī d-Dīn ʿAbd-al-Ḥamīd. Dār Iḥyāʾ at-Turāṯ al-ʿArabī, Beirut, 1984. Vol. I, pp. 89-118. Digitized

- Secondary literature

- Doris Behrens-Abouseif: “Qāytbāy's Madrasahs in the Holy Cities and the Evolution of Ḥaram Architecture” in Mamluk Studies Review 3 (1999) 129–147.

- Christian Décobert: Le mendiant et le combattant. L'institution de l'islam . Éditions du Seuil, Paris, 1991. pp. 331-336.

- Amikam Elad: Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic worship: holy places, ceremonies, pilgrimage . Brill, Leiden, 1995.

- Hassan M. el-Hawary, Gaston Wiet: Matériaux pour un Corpus inscriptionum Arabicarum. Inscriptions et monuments de la Mecque: Ḥaram et Ka'ba. 1.1. Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, Cairo, 1985.

- Maurice Gaudefroy-Demombynes: Le pèlerinage à la Mekke. Étude d'Histoire religieuse. Paris 1923. pp. 1-26.

- Nazmi al-Jubeh: Hebron (al-Ḫalīl): Continuity and integrative power of an Islamic-Arab city . Tübingen, Univ.-Diss., 1991.

- MJ Kister: "Some Reports Concerning Al-Tāʾif" in Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 1 (1979) 1-18.

- Michael Lecker: The 'Constitution of Medina'. Muḥammad's First Legal Document . Darwin Press, Princeton NJ 2004. pp. 165-169. Digitized

- Harry Munt: The holy city of Medina: sacred space in early Islamic Arabia . Cambridge Univ. Press, New York, NY, 2014. pp. 16-93. Digitized

- Francis E. Peters: Mecca: a literary history of the Muslim holy land . Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ, 1994.

- Ḥasan Muḥsin Ramaḍān: Naqd naṣṣ al-ḥadīṯ: Ǧuhaimān al-ʿUtaibī wa-iḥtilāl al-Ḥaram al-Makkī ka-madḫal . Dār al-Ḥaṣād Ṭibāʿa Našr Tauzīʿ, Damascus, 2010.

- RB Serjeant: "Ḥaram and ḥawṭah, the sacred enclave in Arabia" in ʿAbd ar-Raḥmān Badawī (ed.): Mélanges Ṭāhā Ḥusain . Cairo, 1962. pp. 41-58.

- Richard B. Serjeant: "The Sunna Jāmiʿah, Pacts with the Yathrib Jews, and the Taḥrīm of Yathrib. Analysis and Translation of the Documents Comprised in the So-Called 'Constitution of Medina'" in Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (BSOAS) 41 (1978) 1-42.

- Salim Öğüt: "Harem" in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi 1997, Vol. XVI, pp. 127–132. Digitized

supporting documents

- ↑ Hani Al-Lehadani: 'Golden belt' proposed around Holy Haram ( Memento of August 9, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), in: Saudi Gazette , December 30, 2008.

- ↑ An-Nahrawālī: Kitāb al-Iʿlām bi-bait Allāh al-ḥarām . 1857, p. 45.

- ↑ at-Tabarī : Taʾrīḫ al-rusul wa-l-mulūk. Ed. MJ de Goeje. Leiden, 1879-1901. Vol. I, p. 1097, lines 13-14. Digitized

- ^ Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 34.

- ^ Al-Azraqī: Aḫbār Makka . 1858, p. 367.

- ↑ An-Nahrawālī: Kitāb al-Iʿlām bi-bait Allāh al-ḥarām . 1857, p. 45.

- ^ Al-Azraqī: Aḫbār Makka . Ed. Malḥas, 1983, Vol. I, p. 192 digitized .

- ↑ The translation follows the translation of the Koran by Hartmut Bobzin , but the word ḥaram , which Bobzin translates as "sanctuary", is reproduced here as haram.

- ^ Gaudefroy-Demombynes: Le pèlerinage à la Mekke. 1923, p. 6.

- ↑ See also MJ Kister: "Some Reports Concerning Al-Tāʾif" in Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 1 (1979) 1-18. Here p. 9.

- ↑ Muḥammad ibn Ḥabīb al-Baġdādī: Kitāb al-Munammaq fī aḫbār Quraiš . ʿĀlam al-Kutub, Beirut, 1985. pp. 232f. Digitized

- ↑ See Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 33.

- ^ Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, pp. 37–39.

- ↑ Ibn al-Kalbī: Kitāb al-Aṣnām . Cairo 1914. Ed. Aḥmad Zakī Bāšā. P. 18 digitized

- ↑ Peters: Mecca: a literary history of the Muslim holy land . 1994, p. 90.

- ↑ See Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 65.

- ↑ See Ferdinand Wüstenfeld : History of the City of Mecca, edited from the Arabic chronicles. Leipzig 1861. § 113. Can be viewed online here.

- ↑ The original Arabic text is available here .

- ↑ Ibrāhīm Rifʿat Bāšā: Mirʾāt al-ḥaramain Vol. I, p. 227.

- ^ Al-Azraqī: Aḫbār Makka . 1858, p. 361.

- ^ Al-Azraqī: Aḫbār Makka . 1858, p. 379f.

- ^ Al-Azraqī: Aḫbār Makka . 1858, p. 357, line 12ff.

- ↑ Ibrāhīm Rifʿat Bāšā: Mirʾāt al-ḥaramain Vol. I, p. 227.

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the information in the table below is based on al-Ḥuwaiṭān: Aḥkām al-Ḥaram al-Makkī . 2004, pp. 34-40.

- ↑ Ibn Rusta: Kitāb al-Alāq an-nafīsa . 1892, p. 57

- ↑ Ibrāhīm Rifʿat Bāšā: Mirʾāt al-ḥaramain Vol. I, p. 226.

- ↑ Peters: Mecca: a literary history of the Muslim holy land . 1994, p. 21.

- ↑ Yāqūt Ibn-ʿAbdallāh ar-Rūmī : Kitāb Muʿǧam al-buldān . Brockhaus, Leipzig, 1867. Vol. II, p. 222 digitized

- ↑ al-Ḥuwaiṭān: Aḥkām al-Ḥaram al-Makkī . 2004, pp. 40-41.

- ↑ See the Makkah Boundaries map , which summarizes the results of its redefinition.

- ↑ al-Māwardī: al-Aḥkām as-sulṭānīya . 1989, pp. 213f.

- ↑ al-Māwardī: al-Aḥkām as-sulṭānīya . 1989, p. 214.

- ↑ al-Māwardī: al-Aḥkām as-sulṭānīya . 1989, pp. 214f.

- ↑ al-Māwardī: al-Aḥkām as-sulṭānīya . 1989, p. 215.

- ↑ al-Māwardī: al-Aḥkām as-sulṭānīya . 1989, p. 215.

- ^ Al-Qari: al-Maslak al-mutaqassiṭ . 1970, p. 254.

- ↑ Ibrāhīm Rifʿat Bāšā: Mirʾāt al-ḥaramain Vol. I, p. 224.

- ↑ The following list is based essentially on Godefroy-Demombynes: Le pèlerinage à la Mekke. 1923, pp. 19-21 and al-Qārī: al-Maslak al-mutaqassiṭ . 1970, pp. 54f.

- ↑ The statements on the distance in day trips come from Ibrāhīm Rifʿat Bāšā: Mirʾāt al-ḥaramain Vol. I, p. 225.

- ^ Cf. Yāqūt al-Hamawī ar-Rūmī : Kitāb Muʿǧam al-buldān . Ed. Ferdinand Wüstenfeld . Vol. II, p. 651, line 14. Can be viewed online here.

- ^ Ignatius Mouradgea d'Ohsson : Tableau général de l'empire othoman: divisé en deux parties, dont l'une comprend la législation mahométane, l'autre, l'histoire de l'empire othoman vol. III. Paris, 1790. p. 280. Digitized

- ^ Ali Bey : Travels of Ali Bey: in Morocco, Tripoli, Cyprus, Egypt, Arabia, Syria, and Turkey. Between the years 1803 and 1807 . James Maxwell, Philadelphia, 1816. Vol. II, p. 104. Digitized

- ↑ Ibn Hischām : Kitāb Sīrat Rasūl Allāh after Muhammed Ibn Ishāk. Arranged by Abd el-Malik Ibn Hischâm. From d. Hs. On Berlin, Leipzig, Gotha a. Leyden ed. by Ferdinand Wüstenfeld . 2 vol. Göttingen 1858–59. Vol. I, p. 343. Digitized version .

- ↑ See Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 58f.

- ↑ Serjeant: "Ḥaram and ḥawṭah". 1962, p. 50.

- ↑ Online version on Wikisource

- ↑ Abū Yūsuf: Kitāb al-Ḫarāǧ . Dār al-Maʿrifa, Beirut, 1979. p. 104. Digitized

- ↑ See Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 60.

- ↑ See Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 72f.

- ↑ as-Samhūdī: Wafāʾ al-wafā . 1984, Vol. I, p. 102.

- ↑ See Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, pp. 73-77.

- ↑ Shams ad-Dīn al-Maqdisī: Kitāb Aḥsan at-taqāsīm fī maʿrifat al-aqālīm. Ed. MJ de Goeje. 2nd ed. Brill, Leiden 1906. P. 82 digitized

- ↑ Ibn Abī Ḫaiṯama: at-Taʾrīḫ al-kabīr . Ed. SF Halal. 4 Vols. Cairo 2004. Vol. I, p. 353. Digitized .

- ^ Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 87.

- ↑ al-Māwardī: al-Aḥkām as-sulṭānīya . 1989, p. 216.

- ↑ Ibn Abī Shaiba: Kitā al-Muṣannaf . Vol. XIII, p. 125.

- ^ Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 84.

- ^ Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 86.

- ^ Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal: al-Musnad . Ed. Shuʿaib al-Arnāʾūṭ. Muʾassasat ar-Risāla, Beirut, 2008. Vol. V, p. 90. Digitized

- ^ Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, pp. 86, 88.

- ^ Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 88f.

- ↑ Al-Ǧāḥiẓ: Kitāb al-Ḥayawān . Ed. ʿA.-SM Hārūn. 7 vols. Cairo, 1938–45. Vol. III, p. 142. Digitized

- ↑ As-Samhūdī: Wafāʾ al-wafā bi-aḫbār Dār al-Muṣṭafā . 1984, Vol. I, pp. 103f. - See also the Engl. Translated by Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 91.

- ^ Kister: "Some Reports Concerning Al-Tāʾif" 1979, pp. 2, 8f.

- ^ Kister: "Some Reports Concerning Al-Tāʾif" 1979, p. 11f.

- ^ Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal: al-Musnad . Ed. Shuʿaib al-Arnāʾūṭ. Muʾassasat ar-Risāla, Beirut, 2008. Vol. III, p. 32, no. 1416. Digitized .

- ↑ Ibn Qaiyim al-Ǧauziya : Zād al-maʿād fī hady ḫair al-ʿibād . Shuʿaib and ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Arnaʾūṭ. Muʾassasat ar-Risāla, Beirut, 1998. Vol. III, p. 444. Digitized .

- ↑ ʿAbd ar-Razzāq aṣ-Ṣanʿānī: al-Muṣannaf . Ed. Ḥabīb ar-Raḥmān al-Aʿẓamī. Beirut 1983. Vol. XI, p. 134, No. 20126. Digitized

- ↑ Abū ʿUbaid al-Bakrī: Kitāb al-Muʿǧam mā staʿǧam . Ed. Muṣṭafā as-Saqqā. Cairo 1949. p. 1370. Digitized

- ↑ So in particular with Andreas Kaplony: The Ḥaram of Jerusalem 324-1099; temple, Friday mosque, area of spiritual power. Stuttgart 2002 and Michael H. Burgoyne: "The Gates of the Ḥaram al-Sharīf" in Julian Raby and Jeremy Johns (eds.): Bayt al-Maqdis: ʿAbd al-Malik's Jerusalem. Part 1 . Oxford Studies in Islamic Art 9 (1992) 105-24.

- ^ Munt: The holy city of Medina . 2014, p. 25.

- ↑ See Ibn Ḫallikān : Wafayāt al-aʿyān wa-anbāʾ abnāʾ az-zamān . Ed. Iḥsān ʿAbbās. Dār Ṣādir, Beirut n. D. Vol. IV, p. 232. Digitized

- ^ Max van Berchem: Matériaux pour un Corpus inscriptionum Arabicarum. Part II / 1 Syrie du Sud, Jérusalem «Haram» . Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire, Cairo, 1927. p. 24. Digitized

- ↑ Ibn Wāṣil: Mufarriǧ al-kurūb fī aẖbār Banī Aiyūb . Ed. Ḥasanain Muḥammad Rabīʿ and Saʿīd ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ ʿĀšūr. Maṭbaʿat Dār al-Kutub, Cairo, 1977. Vol. IV, p. 241. Digitized

- ↑ ʿIzz ad-dīn Muḥammad Ibn Shaddād: Rauḍ aẓ-ẓāhir fī sīrat al-malik aẓ-Ẓāhir . Ed. Ahmad Hutait. Steiner, Wiesbaden, 1983. p. 350.

- ↑ Al-Jubeh: Hebron (al-Ḫalīl): Continuity and integrative power of an Islamic-Arab city . 1991, p. 209.

- ↑ Al-Jubeh: Hebron (al-Ḫalīl): Continuity and integrative power of an Islamic-Arab city . 1991, p. 216.

- ↑ Quoted from Charles Matthews: "A Muslim Iconoclast (Ibn Taymīyyeh) on the" Merits "of Jerusalem and Palestine" in Journal of the American Oriental Society 56 (1936) 1-21. Here p. 13f. The text is also printed in Ibn Taimīya's fatwa collection: Maǧmūʿ al-fatāwā . Wizārat aš-šuʾūn al-islāmīya, Riyadh, 2004. Vol. XXVII, pp. 14f. Digitized

- ↑ Ibn-Tamīm al-Maqdisī: Muṯīr al-ġarām ilā ziyārat al-Quds wa-š-Šām . Ed. Aḥmad al-Ḫuṭāimī. Dār al-Ǧīl, Beirut, 1994. p. 190.

- ↑ Nazmi al-Jubeh: Hebron (al-Khalil): Continuity and integration power of an Islamic-Arab city . Tübingen, Univ.-Diss., 1991. pp. 214-216.

- ↑ Muǧīr ad-Dīn al-ʿUlaimī: al-Uns al-ǧalīl bi-tārīẖ al-Quds wa-l-Ḫalīl . Ed. Maḥmūd ʿAuda Kaʿābina. Maktabat Dundais, Hebron / Amman 1999. Vol. II, p. 407. Digitized

- ↑ Mehmet Tütüncü: Turkish Jerusalem: 1516-1917; Ottoman inscriptions from Jerusalem and other Palestinian cities . SOTA, Haarlem, 2006. p. 109.

- ^ Max van Berchem: Matériaux pour un Corpus inscriptionum Arabicarum. Part II / 1 Syrie du Sud, Jérusalem «Haram» . Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire, Cairo, 1927. p. 349. Digitized

- ↑ See also Oleg Grabar : Art. "Al-Ḥaram al- Sh arīf" in The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition Vol. III, pp. 173b-175a.

- ↑ See Robert Richardson: Travels along the Mediterranean, and parts Adjacent; in company with the earl of Belmore, during the years 1816-17-18 . Cadell, London, 1822. Vol. II, pp. 281-308. Digitized

- ^ Ernst Gustav Schultz: Jerusalem. A lecture. With a tarpaulin drawn by H. Kiepert . Simon Schropp & Co. , Berlin 1845 p. 28 digitized

- ^ Charles-Jean-Melchior de Vogüé : Le temple de Jérusalem: monographie du Haram-Ech-Chérif, suivie d'un essai sur la topographie de la ville sainte . Noblet & Baudry, Paris, 1864. Digitized

- ↑ Mevlüt Çam: Tarihçe-i Harem-i Şerîf-i Kudsî in Vakıflar Dergisi 48 (Aralık 2017) pp. 195–202.

- ↑ Muḥammad Ṣāliḥ al-Munaǧǧid: Hal al-Masǧid al-aqṣā yuʿtabar ḥaraman? Fatwa, published February 17, 2003, English translation .

- ↑ ʿAbdallāh Maʿrūf ʿUmar: al-Madḫal ilā dirāsat al-Masǧid al-aqṣā al-mubārak . Dār al-ʿIlm li-l-malāyīn, Beirut, 2009. pp. 37–39. Digitized

- ↑ Abū Ǧaʿfar Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan aṭ-Ṭūsī: al-Amālī . Ed. ʿAlī Akbar Ġifārī and Bahrād al-Ǧaʿfarī. Dār al-Kutub al-Islāmīya, Tehran, 1381hš. P. 945 digitized

- ↑ Abū l-Qāsim Ǧaʿfar ibn Muḥammad Ibn Qulawaih: Kāmil az-ziyārāt . Ed. Ǧawād al-Qaiyūmī al-Iṣfahānī. Našr al-Faqāha, [Qum], 1996. p. 451. Digitized

- ↑ Muhammad Bāqir al-Maǧlisī : Biḥār al-Anwār. 3rd ed. Dār Iḥyāʾ at-turāṯ al-ʿArabī, Beirut, 1983. Vol. LXXXXVII, p. 252, no. 47. Digitized