Bluebeard's Castle

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Bluebeard's Castle |

| Original title: | A kékszakállú herceg vára |

Judith (Olga Haselbeck) and Blaubart (Oszkár Kálmán) in the premiere production in 1918 before opening the seventh door |

|

| Shape: | Opera in one act |

| Original language: | Hungarian |

| Music: | Béla Bartók |

| Libretto : | Béla Balázs |

| Premiere: | May 24, 1918 |

| Place of premiere: | Royal Budapest Opera House |

| Playing time: | Around 1 hour |

| Place and time of the action: | the imaginary castle of Duke Bluebeard |

| people | |

|

|

Bluebeard's Castle ( Hungarian original title: A kékszakállú herceg vára ) is a one-act opera composed by Béla Bartók in 1911 with a libretto by Béla Balázs . The world premiere took place on May 24, 1918 at the Royal Opera House in Budapest .

action

In the prologue, a speaker gets the audience in the mood for the following tale: “The castle is old, the legend that goes from it is also old. Listen now, listen. "

During these words the curtain opens and the stage shows a “mighty round Gothic hall” with a steep staircase to a small iron door. There are seven large doors to the right of the stairs. Otherwise the hall is dark and empty and resembles a rock cave. Suddenly the iron door opens. The silhouettes of Judith and Bluebeard are shown in the resulting “dazzlingly bright square”. Judith followed the duke into his castle. He gives her one more opportunity to repent - but Judith is determined to stay with him. She left her parents, brother and fiancé for him. The door slams behind them. Judith slowly feels her way along the damp wall on the left, shaken by the darkness and cold in Bluebeard's castle. She falls down in front of him, kisses his hands and wants to light up the dark walls with her love. To let the day in, the seven locked doors are said to be opened. Bluebeard has no objection. He gives her the first key.

When Judith opens the first door, a long, blood-red glowing beam of light falls through the opening onto the hall floor. Behind the door, Judith, to her horror, recognizes Bluebeard's torture chamber with its bloody walls and various instruments. But she quickly collects herself, compares the glow to a “stream of light” and asks for the key to the second door. Behind this it glows reddish yellow. It is Bluebeard's armory with blood-smeared military equipment. In fact, the rays of light make it brighter in the castle, and Judith now wants to open the other doors as well. Bluebeard first gives her three keys. She can look but not ask. She hesitates for a moment before, after being encouraged by Bluebeard, opens the third door "with a warm, deep ore sound" and a golden ray of light emerges. It is the treasury full of gold and precious stones, all of which should now belong to her. She selects some jewels, a crown and a magnificent cloak and places them on the doorstep. Then she discovers blood stains on the jewelery. Restlessly, she opens the fourth door, through which it shines blue-green. Behind it is the castle's “hidden garden” with huge flowers - but the rose stems and the earth are also bloody. Bluebeard leaves Judith's question who is watering the garden unanswered because she is not allowed to ask him any questions. She impatiently opens the fifth door, through which a "radiant flood of light" enters and blinds Judith for a moment. Behind it, she recognizes the Duke's large country with forests, rivers and mountains, but is irritated by a cloud that casts “bloody shadows”. The interior of the castle itself is now brightly lit. Bluebeard warns Judith about the last two doors, but she insists on opening them too. A quiet lake of tears appears behind the sixth door. “It flies through the hall like a shadow,” and the light dims again. When Bluebeard wants to keep at least the last door locked, Judith hugs him pleadingly. Bluebeard hugs her and kisses her for a long time. Judith, full of premonition, asks him about his previous love affairs. She insists on opening the seventh door and finally receives the key. When she slowly walks to the door and opens it, the fifth and sixth doors close “with a slight sigh”. It's getting darker again. Silver moonlight pours in through the seventh door, illuminating their faces. The three former women of Bluebeard emerge, adorned with crowns and jewels, as embodiments of the times of day morning, noon and evening. Bluebeard puts on Judith the crown, jewelry and cloak from the treasury. As night she has to stand by the side of her predecessors and follow them behind the seventh door. Bluebeard remains in the castle, which has become dark again: "And it will always be night ... night ... night ..."

layout

libretto

The Versmas consists almost entirely of trochaic tetrameters or eight-syllable ballad verses .

The text is characterized by an imaginary musical dialogue that the librettist Béla Balázs had learned from Maurice Maeterlinck . As in Richard Wagner's work, there are frequent word and phrase repetitions and metaphors used analogously to musical leitmotifs .

The dramaturgical structure of the opera corresponds to that of a spoken drama. The introduction in which Judith arrives at Bluebeard's castle is in three parts. The main part, in which she opens the seven doors, is designed as an arc of tension, which gradually grows in the first four doors (torture chamber / armory and treasure chamber / garden) and reaches the climax at the fifth door before returning to it during the last two doors decreases. The epilogue describes the final separation of the two characters.

music

In contrast to the language of the libretto, Bartók's setting was not based on Wagner, but rather on French impressionism . His research into Eastern European folk music at the time the opera was written also plays a role. Folkloric elements and trend-setting harmony are "organically" interwoven.

The dramaturgical concept of the libretto is reflected in the precisely defined play of colors in the scene (which is in contrast to the sparse set design) and in the key system of the music. The overall result is a pitch circle descending in minor thirds with the sequence F sharp - E flat - C - A - F sharp. At the beginning there is a strict pentatonic with the F sharp as the keynote. When the armory is opened, trumpet fanfares sound in E flat major. This also marks the spaciousness of the gardens behind the fourth door. At the dramatic climax at the fifth door, the full orchestra including the organ plays in a brilliant C major to present the great empire of the duke. The lake of tears behind the sixth door is marked in A minor, and Bluebeard's Solitude at the end is again in pentatonic F sharp.

Tonal fifths are added to this basic structure based on the tritone . The opera thus has a "polyfunctional system", as the musicologist József Ujfalussy called it.

Each room has its own compositional characteristics due to the instrumentation and theme. In the torture chamber behind the first door, for example, xylophones and high woodwinds can be heard playing up and down fast scales the size of a tritone. At the armory it's the trumpets already mentioned. A horn solo sounds as a warning to Bluebeard . In the treasury, glittering harps and celesta play in D major.

The blood, which Judith repeatedly noticed, is characterized by a dissonant "guiding tone" with semitone friction . It sounds for the first time to Judith's words “The wall is wet! Bluebeard! “When Judith enters the castle, as she gropes her way along the walls in the darkness. As a result, it becomes increasingly sharp through other instrumentation and increasing pitches until the fifth door is reached. Then he changes the meaning and now represents Judith's obsession.

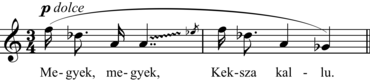

In contrast to the orchestral language, which at times seems almost expressionistic , Bartók treats the vocal parts with great caution. They are more reminiscent of the music of Claude Debussy . The phrases are mostly short. The melodies often have a descending character. In contrast to Debussy, however, Bartók also uses arioso vocal lines instead of the predominant parlando if necessary . The music of the two people is designed differently. The Duke prefers to use folk-song pentatonic scales, while Judith has richer music with chromatic turns and more differentiated rhythms. It is also assigned the symbol of the feminine typical of Bartók, the major seventh chord of the first degree. Its minor version can also be found in the quick figuration of the Tear Lake picture. Bluebeard's castle is considered to be a turning point in the history of Hungarian opera, as this is the first time the style of singing has been specially adapted to the rhythm of the Hungarian language.

Despite the eight-syllable meter of the libretto, Bartók prefers 2/4 and 4/4 bars in his setting.

orchestra

The orchestral line-up for the opera includes the following instruments:

- Woodwinds : four flutes (fourth and first Piccolo , 3rd and 2nd piccolo), two oboes , English horn , three clarinets 1 and 2 in A (, B and Es, third in A and B, and bass clarinet in A and B), four bassoons (4th also contrabassoon )

- Brass : four horns , four trumpets , four trombones , bass tuba

- Timpani , percussion : bass drum , snare drum , tom-tom , pool , suspended cymbal, key xylophone, triangle

- Celesta , organ

- two harps

- Strings : sixteen violins 1, sixteen violins 2, twelve violas , eight cellos , eight double basses

- Incidental music : four trumpets, four alto trombones

Work history

The content of Bartók's only opera deals with a legend circulating in many versions across Europe. Charles Perrault processed them in his fairy tale Bluebeard in 1697 . A series of literary and musical adaptations followed. Opera and operetta versions come from André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry ( Raoul Barbe-bleue, 1789), Jacques Offenbach ( Blaubart , 1866), Paul Dukas ( Ariane et Barbe-Bleue , 1907) and Emil Nikolaus von Reznicek ( Knight Blaubart , 1920).

As a libretto Bartók used the symbolist drama The Castle of Prince Bluebeard by Béla Balázs , the first part of his trilogy Misztériumok ( Mysteries ). It is inspired by the Ariane et Barbe-Bleue of his teacher Maurice Maeterlinck , but deviates significantly from it in terms of content and emphasizes above all the tragedy of the title hero and the idea of salvation. Balázs dedicated this text to Bartók and the composer Zoltán Kodály and published it in 1910. Bartók heard it at a private reading in Kodály's apartment and immediately noticed that the program presented by Balázs, “from the raw material of the Szekler folk ballads, included modern, intellectual inner experiences shape ”(Balázs), also corresponded to his own compositional goal of integrating folk music into modern art music. Kodály showed no interest in setting it to music. Bartók, however, adopted the text almost unchanged. He dedicated the opera to his first wife, Márta Ziegler, and presented it at a composition competition at the Leopoldstadt Casino, which she did not consider performable and rejected. He then had the text translated into German by Emma Kodály-Sandor so that it could be performed abroad. However, this hope was not fulfilled. It was only after the successful premiere of his dance play The Wood-Carved Prince in 1917 that a production of Bluebeard's Castle became possible.

In the meantime, Bartók had already revised the work several times on Kodály's advice. Changes mainly affected the melodies of the vocal parts and the ending. In the original version, Bluebeard's closing words “It will be night forever” was missing. Instead, the pentatonic melody from the beginning was played twice. Bartók also made changes between the first performance and the publication of the piano reduction (1921) and score (1925) and afterwards.

Olga Haselbeck (Judith) and Oszkár Kálmán (Bluebeard) sang at the premiere on May 24, 1918 in the Royal Opera House in Budapest . The speaker of the prologue was Imre Palló. Egisto Tango was the musical director. Dezső Zádor was responsible for the direction. The work was combined with Bartók's dance play The Wood-Carved Prince , which premiered last year . The performance was a great success due to the national importance of the work. Bartók, previously rejected by the audience, was now recognized as a composer. However, there were only eight performances in Budapest before the work was returned to the program in 1936.

The German premiere took place on May 13, 1922 in Frankfurt am Main. In 1929 there was a production in Berlin, in 1938 in Florence and in 1948 in Zurich. Other important productions were:

- 1988: Amsterdam - Director: Herbert Wernicke ; also 1994 in Frankfurt; the scene of the second part was designed as a reversal of the first part

- 1992: Leipzig - production: Peter Konwitschny ; Interpretation as "scenes of a marriage"

- 1995: Salzburg - Director: Robert Wilson

- 1997: Dutch rice opera - production: George Tabori

- 2000: Hamburg - production: Peter Konwitschny ; Interpretation in a world suffocating in trash

The German version of Wilhelm Ziegler's text used in the piano reduction and score editions of 1921/1925 was revised in 1963 by Karl Heinz Füssl and Helmut Wagner.

In 1977 Pina Bausch interpreted the work in Wuppertal as a dance piece called Bluebeard to a "dismembered tape recording" in which the tape recorder was operated by the main actor.

Due to its brevity, the work is usually combined with other short operas or similar pieces such as Stravinsky's Oedipus Rex or Schönberg's monodrama Expectation . In 2007 it was played in Paris together with an orchestral version of Leoš Janáček's song cycle Diary of a Missing Person. The composer Péter Eötvös designed his opera Senza sangue specifically for a performance in front of Duke Bluebeard's castle.

Film adaptations

The opera was filmed several times. Such cinematic adaptations of an opera, often referred to as “film operas”, are to be distinguished from mere documentation of individual stage productions.

- 1963: A German-language film adaptation of the opera by the director Michael Powell (camera: Hannes Staudinger ) with Norman Foster as Bluebeard and Ana Raquel Satre as Judith was produced by Süddeutscher Rundfunk .

- 1968: In 1968 the opera was filmed in Russian and in black and white in the Soviet Union under the title Samok gerzoga Sinej Borody (Замок герцога Синей Бороды). Vitaly Golowitsch took over the direction, Gennady Roschdestvensky the musical direction . Aleftina Evdokimowa played Judith (she was sung by Nadeschda Polyakowa); the role of Duke Bluebeard was split between two actors: Anatoly Werbizki played the young Duke, Semjon Sokolowski the old Duke (Yevgeny Kibkalo sang).

- 1983: The Lithuanian director Jadvyga Zinaida Janulevičiūtė filmed the opera under the title Hercogo Mėlynbarzdžio pilis for Lithuanian television. Gražina Apanavičiūtė (Judith) and Edvardas Kaniava (Bluebeard) sang the leading roles .

- 1988: Directed by Leslie Megahey, the BBC produced a television adaptation in Hungarian with Elizabeth Laurence as Judith and Robert Lloyd as Bluebeard. The Hungarian conductor Ádám Fischer, known as a Bartók expert, took over the musical direction .

- 2005: In 2005 Hungarian television showed a black and white film version of the opera by director Sándor Silló. Under the baton of György Selmeczi, Klára Kolonits sang as Judith and István Kovács as Bluebeard.

Recordings

Duke Bluebeard's castle has appeared many times on phonograms. Operadis names 50 recordings in the period from 1950 to 2009. Therefore, only those recordings that have been particularly distinguished in specialist journals, opera guides or the like or that are worth mentioning for other reasons are listed below.

- Apr. 17, 1950 - Ernest Ansermet (conductor), Orchester Lyrique de l'ORTF Paris.

Lucien Lovano (Duke Bluebeard), Renée Doria (Judith).

Live, in concert from Paris; French version.

Oldest known recording.

Malibran 175 (1 CD), Cantus Classics 500779 (2 CDs). - 7th / 8th October 1958 - Ferenc Fricsay (conductor), Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin .

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (Duke Bluebeard), Hertha Töpper (Judith).

Studio shot, without prologue, shortened, German version by Wilhelm Ziegler.

Csampai / Holland: "Discographic recommendation".

DG 457 756. - 1962 - Antal Doráti (conductor), London Symphony Orchestra .

Mihály Székely (Duke Bluebeard), Olga Szőnyi (Judith).

Studio shot, without prologue, in Hungarian.

Csampai / Holland: "Discographic recommendation".

Mercury 434 325. - November 1965 - István Kertész (conductor), London Symphony Orchestra .

Walter Berry (Duke Bluebeard), Christa Ludwig (Judith).

Studio shot, without prologue, in Hungarian.

Opernwelt CD tip: "Reference recording".

Csampai / Holland: "Discographic recommendation".

Decca 466 377, Decca CD: 443 571 2, London LP: NA, London MC: NA - December 1993 - Pierre Boulez (conductor), Chicago Lyric Opera Orchestra .

László Polgár (Duke Bluebeard), Jessye Norman (Judith).

Studio shot, complete.

Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording 1999.

Deutsche Grammophon CD: 447 040-2. - 1st - 4th February 1996 - Bernard Haitink (conductor), Berlin Philharmonic .

John Tomlinson (Duke Bluebeard), Anne Sofie von Otter (Judith).

Live, in concert from Berlin, complete.

Opernwelt CD tip: "artistically valuable, DDD recording".

EMI CD: 5 56162 2. - 2002 - Iván Fischer (conductor), Budapest Festival Orchestra.

László Polgár (Duke Bluebeard), Ildikó Komlósi (Judith).

Studio shot.

Gramophone : "This recording is vivid and authoritative all the same."

Philips 470 633-2 (1 SACD). - 2009 - Valery Gergiev (conductor), London Symphony Orchestra .

Willard White (Duke Bluebeard), Elena Zhidkova (Judith).

Hungarian with an English prologue.

Gramophone : "For the perfect introduction to Bartók's Bluebeard look no further."

LSO0685 (Hybrid SACD).

literature

- Gabriella Rácz: Béla Bartók / Béla Balázs: "Duke Bluebeard's Castle" (PDF; 842 kB) . In: Kakanien Revisited , No. 09/2006.

- Nicholas Vázsonyi: Bluebeard's Castle. The Birth of Cinema from the Spirit of Opera. In: The Hungarian Quarterly , Vol.XLVI, No. 178 (Summer 2005) ( Memento from February 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

Web links

- Bluebeard's Castle, Sz. 48 (Op. 11) : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Libretto (Hungarian / English)

- Story of Bluebeard's castle in Opera-Guide

- Discography of Bluebeard's Castle at Operadis

Individual evidence

- ↑ The short quotations in this table of contents are taken from the verbatim translation by Wolfgang Binal. Quoted from the program of the Aalto Musiktheater , season 1993/1994.

- ↑ a b c d e f Paul Griffiths: Bluebeard's Castle. In: Grove Music Online (English; subscription required).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Dietmar Holland: Duke Bluebeard's castle. In: Attila Csampai , Dietmar Holland : Opera guide. E-book. Rombach, Freiburg im Breisgau 2015, ISBN 978-3-7930-6025-3 , pp. 1172–1176.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Monika Schwarz: A kékszakállú herceg vára. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater . Volume 1: Works. Abbatini - Donizetti. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-02411-4 , pp. 200-203.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Duke Bluebeard's castle. In: Harenberg opera guide. 4th edition. Meyers Lexikonverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-411-76107-5 , pp. 35-36.

- ↑ a b c d Duke Bluebeard's Castle. Rudolf Kloiber , Wulf Konold , Robert Maschka: Handbook of the Opera. 9th, expanded, revised edition 2002. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag / Bärenreiter, ISBN 3-423-32526-7 , pp. 16-17.

- ↑ May 24, 1918: "Duke Bluebeard's Castle". In: L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia ., Accessed on July 29, 2019.

- ↑ Bluebeard's Castle. In: Reclams Opernlexikon (= digital library . Volume 52). Philipp Reclam jun. at Directmedia, Berlin 2001, p. 1180 ff.

- ↑ Diary of One Who Disappeared (Zápisník zmizelého) in the lexicon on leos-janacek.org, accessed on July 30 of 2019.

- ↑ Senza sangua. Program of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (English, PDF) ( Memento from August 26, 2016 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Bluebeard's Castle in the Internet Movie Database .

- ↑ Замок герцога Синяя Борода (1983) on kino-teatr.ru (Russian), accessed June 30, 2020.

- ↑ Bluebeard's Castle in the Internet Movie Database .

- ^ Discography on Bluebeard's Castle at Operadis.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Béla Bartók. In: Andreas Ommer: Directory of all complete opera recordings (= Zeno.org . Volume 20). Directmedia, Berlin 2005.

- ↑ 41st Annual GRAMMY Awards (1998) , accessed July 29, 2019.

- ↑ David Patrick Stearns: Review of the CD by Iván Fischer on Gramophone , 13/2011, accessed on July 29, 2019.

- ↑ Rob Cowan: Review of the CD by Valery Gergiev on Gramophone , accessed on July 29, 2019.